Abstract

Background

Existing research suggests that parenting stress and demoralization, as well as provision of learning activities at home, significantly affect the child's school readiness in low-income families. However, the degree to which these dimensions of parenting uniquely influence child school readiness remains unclear.

Objective

This study tested the hypotheses that parent demoralization and support for learning are distinct constructs and that they would independently influence child school readiness.

Methods

117 children in Kindergarten with lower literacy and language skills and their parents were recruited from three Northeastern school districts serving primarily low-income families. Parents reported on their depressive symptoms, parenting difficulties, attitudes and behaviors related to learning activities, and the frequency of parent-child conversation at home. Teachers provided reports of the child's school readiness, as indicated by classroom behaviors, approaches to learning, and emergent language and literacy skills. Factor analysis and structural equation modeling were used to test the study hypotheses.

Results

Parent demoralization and support for learning emerged as distinct constructs based on factor analysis. Structural equation models revealed that parent demoralization is negatively associated with child school readiness, whereas parent support for learning is positively associated with child school readiness. Neither parenting construct mediated the effects of the other.

Conclusions

Among low-income families with children at high risk for child school maladjustment, parental demoralization and support of learning opportunities at home appear to independently influence the child's school readiness. Parent-based interventions targeting child school readiness would likely benefit from enhancing both parental self-efficacy and provision of learning activities.

Longitudinal research has identified a set of child readiness skills, measured at school entry, that strongly predict subsequent school adjustment and achievement (Duncan et al., 2007; Romano, Babchishin, Pagani, & Kohen, 2010). These include the oral language and emergent literacy skills that support reading and classroom engagement (Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony, 2000), as well as self-regulatory skills that foster adaptive approaches to learning in school, such as the capacity to participate cooperatively in the classroom, follow directions, control attention, and sustain task involvement (Blair, 2002; McClelland, Acock, & Morrison, 2006).

Prior research suggests that the quality of parent-child interactions during early childhood plays a particularly important role in promoting the development of these school readiness skills (Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010; Eccles & Harold, 1996). Correspondingly, a number of parent-focused interventions have been developed to enhance parenting skills and thereby support the school readiness of at-risk children (reference omitted for blind review). Yet, it has proven difficult to recruit and retain parents in these school readiness interventions, with recruitment rates typically in the range of 30% to 50% of the eligible population and drop-out rates as high as 50% of those who start the intervention (Brotman et al., 2011; Kaminski, Stormshak, Good, & Goodman, 2002; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001).

It is notable that most parent-focused intervention efforts, such as those cited above, focus on low-income parents, because delays in child school readiness are more prevalent among children growing up in poverty (Campbell & von Stauffenberg, 2008; Ryan, Fauth, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). It is also the case that parents living in low income families often face multiple stressors with limited social support to facilitate coping (Galster, 2012; Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, & Duncan, 1994). Rates of maternal depressive symptoms are often high, and these are associated with reduced parent responsiveness and heightened parental irritability (Kam, Greenberg, Bierman, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group [CPPRG], 2011; Wright, George, Burke, Gelfand, & Teti, 2000). Moreover, maternal depression has been linked to lower scores on measures of cognitive and motor development in preschool children, even after controlling for SES and other family demographic variables (Petterson & Albers, 2001).

It is possible that school readiness interventions for parents have paid insufficient attention to parental attitudes and feelings, particularly feelings of emotional distress or demoralization that may undermine parental efforts to provide learning support for their young children. This study addressed this issue, by examining the degree to which child school readiness skills at kindergarten entry were associated with: 1) low levels of parental involvement and learning support for the child, and 2) high levels of parent demoralization, including depressed mood and feelings of parental inadequacy. It further examined the possibility that parental demoralization was linked indirectly with child school readiness delays, via its association with low levels of learning support.

Parent Support for Learning and Child School Readiness

Substantial research has linked frequent parent-child conversation, reading, and learning activities in the home with child school readiness. For example, naturalistic observations demonstrate that family language use and literacy activities have a powerful effect on young children's learning and later school adjustment (Eccles & Harold, 1996; Hart & Risley, 1995). Parents who frequently talk with their children, point out and explain things in the environment around them, and comment on thoughts and feelings help to shape the child's attention skills and build the child's oral language skills and understanding of narrative (Hart & Risley, 1995; Nord, Lennon, Liu, & Chandler, 2000; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998). Similarly, parents' self-reports of the frequency of parent-child literacy experiences, such as teaching children to identify letters or write their names, are also related to children's scores on measures of emergent literacy (Senechal, 2006), and the frequency and quality of book reading at home is related to vocabulary growth (Lonigan & Whitehurst, 1998; Scarborough, 2001). Conversely, low levels of parental involvement and a failure to provide a cognitively stimulating home environment attenuate the pace of language development (Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1994). Parent beliefs regarding their responsibility to involve themselves in their children's learning also appear to be linked with children's learning (Drummond & Stipek, 2004; Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997). Cheadle (2008) identified a pattern of parent involvement that he termed “concerted cultivation,” which included high rates of verbal interaction with children, a tendency to provide children with structured, extracurricular learning opportunities (e.g., such as music lessons), and a high degree of engagement with children's teachers and other school personnel. This pattern predicted children's general knowledge in kindergarten as well as math and reading achievement in first and second grades.

High levels of parent support for learning are more likely to occur in families with higher SES than in low-income families (Cooper, Crosnoe, Suizzo, & Pituch, 2010; Guo & Harris, 2000; Senechal, 2006). Indeed, low levels of parental support for learning explain and mediate much of the impact that contextual risk associated with low SES (e.g., single parenthood, life stress) has on child reading and mathematics skills in early elementary school (Burchinal, Roberts, Zeisel, Hennon, & Hooper, 2006).

Parent Demoralization and Child School Readiness

One of the factors that may reduce the positive involvement and learning support of low-income mothers with their children is the level of life stress they experience. Mothers in low income families are particularly likely to experience an accumulation of risk factors, including financial strain, poor living conditions, single-parent status, and social isolation, that increase the stress of daily life and reduce sources of psychosocial support (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005). Together, these factors can undermine parenting efficacy and contribute to a developmental context affecting children that is more unpredictable, less stimulating, and less responsive than that experienced by socioeconomically advantaged children (Foster, Lambert, Abbott-Shim, McCarty, & Franze, 2005; Lengua, Honorado, & Bush, 2007; McLoyd, 1998).

Low-income mothers of young children are at heightened risk for depression, with prevalence rates estimated at 40% to 60%, compared to prevalence rate among mothers in the general population of 5% to 25% (Knitzer, Theberge, Johnson, & National Center for Children in Poverty, 2008). Children of depressed mothers are at elevated risk for the development of behavioral problems, including both internalizing and externalizing disorders (see Cummings & Davies, 1994, for a review).

The negative impact of maternal depression appears mediated, at least in part, by its impact on parent-child interactions. Depressed parents are more withdrawn, more inconsistent and unresponsive, and more negative and critical in their interactions with their children than are healthy parents (Kam et al., 2011; Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare, & Neuman, 2000).

In addition to experiencing depressive symptoms, low income parents are more likely to feel inadequate in the parenting role, contributing to inconsistent parenting and the perception that they are unable to effectively manage their child's behavior (Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, Lengua, & CPPRG, 2000). General feelings of helplessness associated with depressed mood and the specific feelings of low self-efficacy in the parenting role are likely inter-related, as each reflects a sense of being overwhelmed by one's life situation. Both have been associated with parenting difficulties such as inconsistent and lax parenting (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Inconsistent parenting, in turn, may exacerbate oppositional-defiant behaviors in children and reduce support for the development of child self-regulatory skills (Campbell & von Stauffenberg, 2008; Stormshak et al., 2000). Whereas sensitive and contingent parental responding fosters the development of sustained attention and self-regulation skills (Landry, Smith, Swank & Miller-Loncar, 2000; Lengua et al., 2007), inconsistent and chaotic family circumstances impede self-regulatory skill development and thereby undermine child school readiness (Burchinal, Vernon-Feagans, Cox, & Key Family Life Project Investigators, 2008). Thus, parent demoralization may negatively affect child school readiness by diminishing the quality of parent-child interactions and decreasing parental warm involvement, consistency, and responsiveness that, in turn, negatively affect the development of the child's self-regulation capacities necessary for successful adjustment to school.

The Association between Parent Demoralization and Support for Learning

Most of the existing research on parent contributions to child school readiness has focused on either parent demoralization (e.g., parental depression, parenting difficulties) or on parent support for learning (e.g., reading beliefs and activities, learning activities at home) – but not both. Several prior studies that have examined both dimensions suggest that they jointly support the development of academic and social-emotional skills related to child school readiness. Within normative samples, a study by Baker et al. (2012), using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998-1999 (ECLS-K), found that parental reading to the child, providing more books at home, and setting bedtimes positively predicted the child's reading achievement and approaches to learning, whereas children whose parents reported often being too busy to play together scored lower in reading achievement. Another study by Martin et al. (2010), drawing from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), found that maternal supportiveness, a composite of parenting behaviors related to the provision of emotional sensitivity and support as well as cognitive scaffolding and teaching when the child was 54 months of age, predicted teacher-rated academic and social competence and child academic achievement at school entry. Paternal supportiveness also predicted the child's social competence in Kindergarten and moderated the effect of maternal supportiveness, increasing academic competence among children whose mothers scored low on supportiveness at age 54 months.

Few studies that have examined aspects of parental demoralization and support for learning specifically in the context of socio-economic risk have also suggested that both dimensions of parenting significantly influence the child's school readiness. For instance, Dotterer et al. (2012) found that sensitive parenting, a construct reflecting affectively sensitive and supportive behaviors as well as cognitively stimulating behaviors, positively mediated the relationship between SES and child pre-academic knowledge among European American children, whereas negative and intrusive parenting behaviors mediated the link between SES and lower pre-academic knowledge for both European-American and African-American children. Similarly, Mistry et al. (2010) found that language stimulation and maternal warmth improved child school readiness (as indicated by cognitive and academic achievement, attention and behavioral regulation, and social behaviors) among families living in poverty, even after accounting for cumulative risk found in the child's ecology. A longitudinal study by Chazan-Cohen et al. (2009) examined parental depressive symptoms, stress, home learning environment, and supportive behaviors among participants of the Early Head Start program and found that initial levels and changes in these parenting factors between child age 14 months to 5 years influenced the child's pre-Kindergarten school readiness, as indicated by behavior problems, approaches toward learning, emotion regulation, vocabulary, and letter-word identification abilities, in expected directions.

Overall, studies with both representative and low-SES samples indicate that parent demoralization and support for learning simultaneously influence child school readiness. However, in order to better inform intervention efforts targeting child school readiness in low-SES households, it is important to study the extent to which they uniquely and differentially affect child school readiness among children at greatest risk for academic maladjustment. Additionally, it is yet unclear from existing research whether these parenting dimensions mediate the effect of the other. For instance, parent demoralization may have a negative effect on child school readiness because it lowers parent involvement in learning activities. Parental depression and self-efficacy are inversely correlated (Fox & Gelfand, 1994), and parents with low self-efficacy are less likely to persist when confronted with challenges and are thus less likely to remain involved in their children's education than parents who feel more efficacious and effective (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997). Thus, parents who feel depressed and challenged by their children's behavior may be less likely than other parents to engage actively in home-based learning activities such as book reading, because they lack the energy or confidence to do so (Jones & Prinz, 2005). However, this link has not yet been demonstrated, and it is not yet known whether the association between parent demoralization and child school readiness is robust once parent support for learning is accounted for. This is specially an important issue to examine among families that are predominantly low in SES, where risk for child learning difficulties is heightened.

The Present Study

The current study aimed to fill these gaps and examine the effects of both parent demoralization and parent support for learning on teacher-rated readiness skills of kindergarten children in schools serving primarily low-income families. Kindergarten children were screened for low reading readiness at school entry. Their parents completed ratings describing depressive symptoms and parenting difficulties. Parents also described their attitudes and activities associated with the provision of support for child learning at home (e.g., interactive reading, teaching activities, language use). Child school readiness was assessed by kindergarten teachers and included emergent literacy and self-regulation skills. We hypothesized that the parenting measures would reflect two distinct domains of parenting (e.g., demoralization and support for learning), which would be inversely correlated. In addition, we anticipated that these two dimensions of parenting would differentially impact children's school adjustment, with parental demoralization linked with lower levels of child school readiness, and parent support for learning linked with higher levels of child school readiness.

Method

Participants

One hundred and seventeen Kindergarten children and their parents were recruited from three Pennsylvanian school districts that primarily served low-income families. The mean child age at time of testing was 5.71 years (SD = .31), and the sample contained roughly equivalent numbers of females (n = 57) and males (n = 61) and was racially diverse (36% White; 36% Black; 12% Hispanic; 11% Mixed; 5% “Other”). A majority (n = 114) of the parents in the study were biological parents (108 female and 6 male), two were step-parents, and one was a grand-parent. Most of these parental figures had high school education or less (72%) and were working (63%). Roughly a third of the participating parents were married (37%) and the rest were single (40%) or living with a partner (23%). English was typically the only language spoken at home (n = 103; 88% of the sample), although ten (9%) families were bilingual in both English and Spanish, and four families spoke another language (3%). Eighteen teachers provided reports of child school readiness variables.

Procedures

Institutional IRB approval was obtained for the following procedures. Recruitment took place through the child's school, with flyers sent home to all kindergarten students announcing a study evaluating parent-focused learning materials for children with low reading readiness. Unless parents declined, they were contacted by telephone, and permission was obtained for their children to receive an individual developmental assessment at school to determine eligibility. Children who scored more than one standard deviation below the national mean on standardized tests of literacy and language skills were considered eligible for the study. Their parents were visited at home in October-November by trained research assistants who attained full informed consent and collected the parent report measures used in this study. Research assistants followed a standard script and read through all parent interview measures in the same order as parents provided their responses. To collect teacher data, research assistants attained informed consent from teachers and then provided teachers with a packet of measures. After explaining the rating forms, they were left with classroom teachers to complete on their own. Distribution of the teacher rating forms began 6 weeks after the start of Kindergarten (mid-October) and the forms were all completed by the end of November. This time frame assured that teachers were familiar with the children they were rating. Parents received $20 and teachers received $10 compensation for completing the measures. Three of the recruited children were excluded from the study due to a significant hearing impairment (n = 1), low English proficiency that prevented a valid assessment (n = 1), and an unresolved temporary custody situation (n = 1). All research procedures followed the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association and were approved by the university's IRB.

Measures

Parent demoralization

Parent demoralization was assessed using two self-report measures that were rated parents. Parental dysphoria and other depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a well-validated 20-item self-report measure with good internal consistency (estimated α = .85) and discriminant as well as convergent validity (Radloff, 1977). Parents reported the frequency with which they experienced depressive symptoms in the past week using a four-point scale (ranging from 1 = rarely, less than one day during the week to 4 = almost all the time, 5-7 days of the week). Items were averaged to create an overall score (α = .88), with a possible range of 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater symptoms of depression.

Parenting difficulties characterized by feelings of unpredictability and low efficacy in the parenting role were assessed using 7 items drawn from Strayhorn and Weidman's (1988) Parent Practices Scale, a 34-item measure with adequate internal consistency (α = .78) and convergent validity. On these items, parents described the frequency with which they felt overwhelmed, inconsistent, and ineffective in the parenting role (e.g., “How often are you just too tired or worn out to make your child behave the way she/he should?” “How often do you give in to your child's demands because you don't want to be embarrassed in public?” “How often do you change your mind about a punishment after you have given it?”). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = almost never to 5 = fairly often, and averaged to create a total score (α = .83). Possible total scores thus ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating difficulty providing consistent and effective parenting behaviors.

Parent support for learning

Parents also completed four paper, self-report measures of their support for learning, describing attitudes and behaviors related to the use of learning activities at home. On the 40-item Parent Reading Belief Inventory (PRBI; DeBaryshe, 1995; DeBaryshe & Binder, 1994), parents described their beliefs and attitudes regarding their role in teaching their child to read, noting how much they agreed with statements such as “I am my child's most important teacher”; “I read with my child so he/she will learn the letters and how to read simple words”; “I feel warm and close to my child when we read.” Items were rated on a four-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree, and averaged to obtain a total score that could range from 1 to 4, reflecting positive parental beliefs and attitudes about supporting literacy at home (α = .95). The PRBI has adequate internal consistency (α = .88), test-retest reliability (α = .79), and has been validated against measures of home reading activities (DeBaryshe & Binder, 1994).

Parent beliefs about their role in supporting their child's education and schooling, or role construction, were measured using the Role Activity Beliefs scale (Walker, Wilkins, Dallaire, Sandler, & Hoover-Dempsey, 2005). On this 10-item scale, parents used a 4-point Likert scale to indicate their agreement (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree) with statements such as, “I believe it is my responsibility to help my child with homework” and “I believe it is my responsibility to explain tough assignments to my child.” The measure has adequate reliability (α = .83) and has shown divergent validity compared to parental liking of the school (Walker et al., 2005). Ratings were averaged to create a total score (α = .83), which can range from 1 to 4, with higher scores reflecting greater parental beliefs that they have an active role to play in their child's education.

In addition, eight questions developed for this study (Home Activities Questionnaire) assessed the regularity with which the parent engaged in specific school readiness learning activities with the child at home (e.g., “When was the last time you tried to teach your child the names of letters?”; “When was the last time you counted out something with your child?”). Responses, reflecting the number of days since the activity had taken place, were averaged to obtain a mean score (α = .89) and reverse-scored so that higher scores indicate greater regularity with which the parent engages in learning activities with the child.

Finally, the frequency and length of parent-child conversations was assessed using four items developed for this study (e.g., “How many times in a typical week do you and your child have a conversation that lasts at least 10 minutes or more?”; “In general, how easy is it to get your child to talk about what's on his/her mind?”). Responses were scaled to range from 0 to 5 and averaged to create a score indicating the availability of the parent for parent-child conversation (α = .41).

Child school readiness

Four teacher-rating measures were used to assess child school readiness. Attention skills, including concentration and ability to follow directions were measured using the ADHD Rating Scale (DuPaul, 1991). Teachers rated eight items related to inattention (e.g., “Has trouble staying focused”; “Is easily distracted”; “Has trouble following directions”) using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 3 = very much. The measure has good internal consistency (α = .95) and test-retest reliability (α = .95) and has been validated with both other parent and teacher-reports of ADHD symptoms, coded observations of on-task child behaviors in the classroom, and standardized academic test scores (DuPaul, 1991). Items were reverse-scored so that higher scores indicated fewer inattention symptoms and then averaged to create an overall indicator of attention with a possible range of 0 to 3 (α = .95).

Eight items from the Learning Behaviors Scale (LBS; McDermott, 1999) were used to assess child motivation, engagement, and goal-oriented learning at school (e.g., “Sticks to a task with no more than minor distractions”; “Is reluctant to tackle a new task”; “Says task is too hard without making much effort to attempt it”). Items were rated using a three-point scale (0 = does not apply, 1 = sometimes applies, 2 = most often applies) to describe the student's typical classroom behavior in the past two months. The Competence Motivation scale, from which items were taken, shows good internal consistency (α = .85), test-retest reliability (minimum α = .91), and convergent, divergent, and incremental validity based on measures of cognitive abilities and academic achievement (McDermott, 1999). Ratings were scored such that higher scores reflected more positive learning behaviors and averaged to create a summary score (α = .87) with a possible range of 0 to 2.

Classroom engagement was measured using eight items describing positive classroom participation (“This child is able to sit at a table and do work”; “This child seems enthusiastic about learning new things”; α = .95) and six items describing disengagement or withdrawal (e.g., “Low energy, lethargic, or inactive”; “Keeps to him or herself, tends to withdraw”; α = .86) drawn from a prior study of school readiness (Bierman, Torres, Domitrovich, Welsh, & Gest, 2008). All items were rated using a six-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree) and averaged to create an overall score with potential range of 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting greater positive classroom engagement (α = .95).

Finally, teachers used 23 items to describe children's language and emergent literacy skills. Twelve items were drawn from the Academic Rating Scale (ARS) created for the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Kindergarten Class of 1998-99 (ECLS-K) (Rock & Pollack, 2002) and required teachers to rate skill attainment (e.g., “This child uses complex sentence structures”; “This child writes simple word from memory”; α = .96) using a five-point scale that ranged from 0 = not yet to 4 = proficient. The ARS has shown good reliability and has been validated against measures of reading and academic achievement (Rock & Pollack, 2002). In addition, 11 items developed for this study required teachers to make relative judgments about the child's skill level (e.g., “The complexity and length of the sentences this child typically uses”; “The child's ability to pronounce words correctly”; α = .97) relative to same-age peers, rated on a five-point scale ranging from (-2) = “More than 1 year behind other children his or her age” to (+2) = “More than 1 year ahead of other children his or her age”. Ratings were averaged to create an overall score representing the child's language and emergent literacy skills (α = .97), with higher scores reflecting greater emergent literacy skills.

Because some of the measures contained items developed for the current study and because we used “parceling,” or combined multiple items for each observed variable, appropriateness of parceling for structural equation modeling was examined (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). The reliability, item-total correlations, factor analysis of the items for each measure were examined to check the uni-dimensionality of the measure and appropriateness of each item for assessing the observed variable.

Analytic Plan

First, descriptive analyses were conducted, and effects of demographic variables on study variables were examined using one-way ANOVA. Bivariate correlations were used to examine associations among measures of parental demoralization, parental support for learning, and child school readiness. Then, to confirm the two hypothesized domains of parenting, a factor analysis was undertaken. Based on the results of the factor analysis, to determine whether the observed variables were satisfactory indicators of the latent constructs and to examine bivariate relations among the latent constructs, a measurement model was estimated using structural equation modeling with robust weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV). This estimator uses a diagonal weight matrix to estimate parameters and is appropriate for use with small to moderate sample sizes containing censored and continuous variables (Byrne, 2012). Then, structural equation models were estimated in order to test the hypothesized model of dual parenting influences on child school readiness, For both the measurement model and the structural equation model, means and residual variances of the observed indicators and the variances of the latent variables were estimated, and the residuals for observed indicators were not inter-correlated. Finally, the presence of mediating or indirect effect, referring to the effect of a predictor variable on the dependent variable through its influence on a mediator, was estimated using structural equation modeling, to see if each parenting dimension mediated the effect of the other on child school readiness, the outcome construct. Indirect effects, referring to the total change in child school readiness caused by one parenting dimension's influence on the mediating dimension, were estimated using procedures described in Muthén (2011), which estimates the indirect effect as a product of the coefficients for the pathway from the predictor to mediator and that from the mediator to the outcome variable. Standard errors for these indirect effects were estimated using bootstrapping methods. Adequacy of overall model fit was assessed using the following indicators: A non-significant (p-value greater than .05) chi-square test statistic, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of at least .95, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of less than .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, 2006), and Weighted Root Mean Square Residual of less than .90 (Muthén, 1998-2004). Analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 and Mplus 7, using maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Distributional properties of each variable was checked for normality, and the only variable showing significant departure from normality based on skewness and kurtosis was the time elapsed since parents last participated in learning activities at home (“Home activities”). Because this variable was censored, it was treated as such in applicable analyses. ANOVAs (and Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis Tests for the home activities variable) were used to examine potential differences in parenting or school readiness associated with the child's sex, race, or the household socio-economic status (SES) assessed using the Hollingshead index (Hollingshead, 1957). Compared to girls, boys experienced lower levels of parent-child conversation. Boys also exhibited lower levels of attention, engagement in learning, classroom participation, and emergent literacy skills than girls, according to teacher ratings. No differences emerged by race or SES.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for the Study Variables.

| Variable | M(SD) | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting | |||

| Parenting difficulties | 2.55 (.90) | 1.00 | 4.29 |

| Depression | 1.14 (.50) | .40 | 2.60 |

| Parent-child conversationa | 2.94 (.73) | .80 | 4.50 |

| Beliefs about reading | 3.37 (.34) | 2.55 | 4.00 |

| Role construction | 3.46 (.35) | 2.60 | 4.00 |

| Home activities | 54.86 (7.86) | 0 | 59.88 |

| Child School Readiness | |||

| Attentionb | 1.95 (.85) | 0 | 3.00 |

| Learning behaviorsc | 1.46 (.46) | .25 | 2.00 |

| Classroom engagementd | 4.55 (.97) | 1.57 | 6.00 |

| Language & literacy skillse | 1.52 (.70) | 0 | 3.17 |

Note. N = 117. Means for all parenting measures, except home activities, represent average item scores.

Parents of girls exhibited higher scores than those of boys, F(1, 115) = 7.89, p = .01.

Girls also scored significantly higher than boys on the following:

F(1, 115) = 14.14, p < .001.

F(1, 115) = 9.02, p = .003.

F(1, 115) = 10.52, p = .002.

F(1, 115) = 7.00, p = .01.

Relations among variables were examined using bivariate correlations, which are presented in Table 2. As expected, significant correlations emerged among the two measures reflecting parent demoralization (e.g., parenting difficulties and depressive symptoms). Similarly, three of the measures reflecting parental support for learning were significantly inter-correlated (e.g., beliefs about reading, parental role construction, and frequency of home learning activities). However, parent-child conversations were more strongly correlated with measures of demoralization than measures reflecting parent support for learning. The four teacher-rated measures of child school readiness formed a cohesive set, linked by significant inter-correlations (e.g., attention skills, learning behaviors, classroom engagement, and emergent literacy skills). Of the 24 correlations linking parent-reported measures of parenting with teacher-rated measures of child school readiness, 15 were statistically significant, and all were in the anticipated direction. Only parent-reported home learning activities had no significant associations with teacher-rated indices of child school readiness.

Table 2. Intercorrelations Among Parenting and Child School Readiness Variables.

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parenting difficulties | - | ||||||||

| 2. Depression | .49** | - | |||||||

| 3. Parent-child conversation | -.29** | -.38** | - | ||||||

| 4. Beliefs about reading | -.23* | -.15 | .21* | - | |||||

| 5. Role construction | -.12 | -.10 | .17 | .67** | - | ||||

| 6. Home activities | -.17 | -.11 | -.25** | .34** | .21* | - | |||

| 7. Attention | -.19* | -.17 | .27** | .18 | .19* | .05 | - | ||

| 8. Learning behaviors | -.23* | -.18* | .28** | .22* | .17 | .08 | .80** | - | |

| 9. Class engagement | -.20* | -.18* | .30** | .26** | .21* | .18 | .76** | .81** | - |

| 10. Language/literacy skills | -.26** | -.21* | .15 | .25** | .15 | .07 | .57** | .65** | .72** |

Note. N = 117. Pearson's correlation coefficients are reported, except for bivariate correlations involving Home activities (6), for which Spearman's correlation is reported due to violation of the normality assumption.

p < .05;

p < .01.

To investigate whether measures of parenting were reasonable indicators of the two hypothesized latent constructs (e.g., parent demoralization and support for learning), the six parenting measures were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation. Two factors emerged with Eigenvalues greater than one (see Table 3). The first factor had an Eigenvalue of 2.34, explained 39% of the variance, and was defined by parental reading beliefs, role construction, and home learning activities. The second factor had an Eigenvalue of 1.34, explained 22% of the variance, and was defined by parenting difficulties, depressive symptoms, and low levels of parent-child conversation. These two factors validated the dimensions of parent support for learning and demoralization. The only unexpected finding was that parent-child conversations loaded with parent demoralization and not with parent support for learning, and hence was included as an indicator of parent demoralization. To facilitate the interpretation of subsequent analyses, the variable for parent-child conversations was reverse-scored to be consistent with the construct of parental demoralization, such that higher scores reflected parental unavailability for parent-child conversations.

Table 3. Factor Loadings for Exploratory Factor Analysis of Parenting Scales.

| Measure | Factor 1: Support for Learning | Factor 2: Demoralization |

|---|---|---|

| Parenting difficulties | -.10 | .76 |

| Depression | -.05 | .84 |

| Parent-child conversation | .20 | -.65 |

| Beliefs about reading | .88 | -.12 |

| Role construction | .89 | -.01 |

| Home activities | .52 | -.28 |

Note. Analysis used Varimax rotation. Factor loadings above .40 are in boldface.

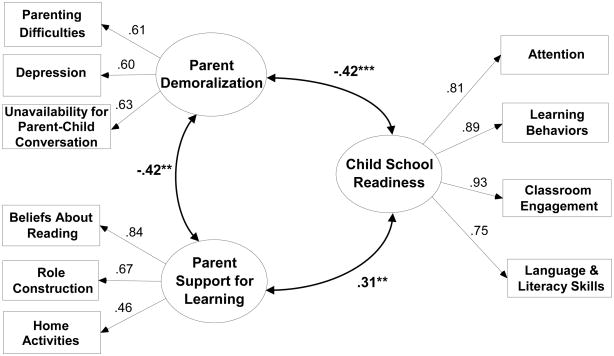

Measurement Model

Next, a measurement model was estimated to examine the relations among latent constructs and their observed indicators (see Figure 1). This measurement model had a satisfactory fit to the data, χ2 (32, N = 117) = 30.78, p = .53. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 1.00, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was .00, and the Weighted Root Mean Square Residual (WRMR) was .43. The model showed that all of the observed variables were appropriate indicators of the latent constructs, with statistically significant loadings at the p < .001 level. Although one of the item loadings was small (home learning activities, with standardized coefficient of .46), it substantially improved the model fit and was thus retained in the model.

Figure 1. The Measurement Model.

A measurement model showing the relationships among latent constructs and their observed indicators (n = 117). Standardized coefficients are shown. All relationships between observed indicators and latent constructs were significant at the .001 level. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Additionally, the measurement model showed that the latent constructs were related in the hypothesized manner. Parent demoralization was negatively associated with both parent support for learning, r = -.42, p = .001 and child school readiness, r = -.42, p = .001, and parental support for learning was positively associated with child school readiness, r = .31, p = .002.

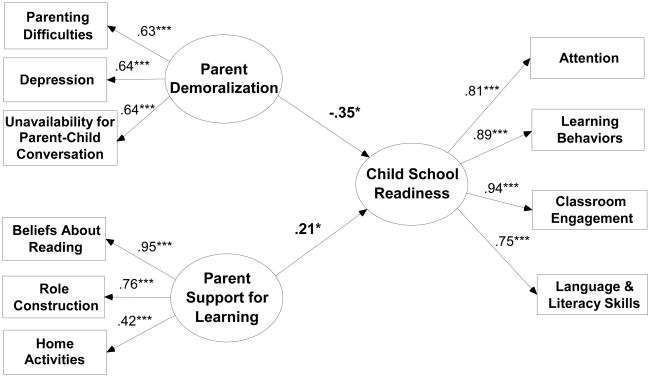

Structural Equation Model

A structural equation model was estimated in order to determine whether parent demoralization and parent support for learning were independently associated with child school readiness as hypothesized (see Figure 2). The model had a satisfactory fit to the data, χ2 (32, N = 117) = 34.53, p = .35. The CFI for the model was .99, and the RMSEA was .03. Modeling of the covariance between the two constructs and controlling for the effect of SES on child school readiness did not significantly improve model fit and was thus excluded from analysis. Both of the path coefficients in the model were statistically significant at the .05 level, with a standardized path estimate between parent demoralization and child school readiness of β = -.35, t (83) = -3.92, p < .001, and between parent support for learning and child school readiness of β = .21, t 83) = 2.38, p = .02.

Figure 2. The Structural Equation Model.

Structural equation modeling showing the influence of parent demoralization and support for learning on child school readiness (n = 117). Standardized coefficients are shown. * p < .05; *** p < .001.

To examine whether parent support for learning mediated the effect of parent demoralization on child school readiness, indirect effects were estimated using procedures by Muthén (2011). Indirect effects of support for learning were non-significant. Thus, parent support for learning did not account for the link between parent demoralization and lower child school readiness. Exploratory analysis examining indirect effects of parent demoralization also did not reveal a significant indirect effect, suggesting that the two domains of parenting have distinct and unique direct effects on child school readiness.

Discussion

This study examined associations between two dimensions of parenting and the school readiness of at-risk children entering kindergarten. As hypothesized, parent demoralization and parent support for learning emerged as two distinct dimensions, each significantly associated with teacher-rated child school readiness. Parental demoralization and support for learning were negatively correlated, and each of these aspects of parenting explained unique variance in child school readiness. We found support for the hypothesis that parental demoralization is negatively associated with child school readiness and that parental support for learning is positively associated with school readiness, even after accounting for the other parenting construct. The findings were robust even when controlling for the effects of SES, which was not found to be a significant predictor of child school readiness. The results of this study validate the conceptualization of the two distinct domains of parenting as independent influences on child school readiness among low-SES families, and this was also supported by tests of mediation, which showed that neither domain of parenting accounted for the influence of the other domain on the child's school readiness.

These findings add to the extant literature on this topic by demonstrating the concurrent independent and complementary associations of these two parenting domains with child school readiness. Although parenting quality and support for learning have often been studied as a single dimension affecting child school readiness in previous studies (e.g., Dotter et al., 2012; Kiernan & Mensah, 2011; Lugo-Gil & Tamis-LeMonda, 2008; Lunkenheimer et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2010), our findings suggest the importance of examining their impact on child school readiness separately.

The Prevalence of Parental Demoralization in Low Income Families

Low-income parents of young children often face multiple stressors, including financial strain, low levels of social support, and challenging family and work conditions (Lengua et al., 2007; Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005). Hence, we anticipated that many would struggle with feelings of depressed mood and feel overwhelmed by parenting challenges. Indeed, in this sample of at-risk children from low-income communities, 38% of the parents reported a level of depressive symptoms that placed them above the clinical cut-off for depression, and 29% reported that they lacked the energy or efficacy to follow-through consistently with their parenting plans “sometimes” to “frequently.” As expected, depressed mood and parenting difficulties were significantly inter-correlated (r = .49) in this sample, probably reflecting the impact of parenting challenges on parental mood and the impact of depressed mood on lowered parenting efficacy. In addition, depressed mood and parenting difficulties were also significantly correlated with low levels of parent-child conversation, and these three measures loaded together in the factor analysis. Although we initially conceptualized parent-child conversation as a measure of parent support for learning, empirically it was more closely aligned with measures of parent demoralization. These findings may reflect the degree to which parents' psychological availability and responsiveness support their engagement in parent-child conversation. When parents feel depressed and overwhelmed by parenting challenges, they may be less available for and responsive to their children, and hence support less frequent and sustained conversations with their young children. Child effects may also contribute, such that children who are more challenging behaviorally and have less well-developed language skills increase parenting difficulties and respond less to parent conversational efforts. The prevalence of parental demoralization in this study suggests the importance of considering parent feelings and attitudes in the design of interventions seeking to increase parental support for learning to enhance child school readiness.

Implications for Practice

A number of interventions have been designed for low income families, to encourage parents to engage actively with schools and spend more time reading, talking, or playing with their children, thereby targeting support for learning. For example, in the Parent-Child Home Program (Levenstein et al., 1998), home visitors deliver toys, books, and learning games, modeling and discussing their use with parents. The goal is to increase positive parent-child interaction and conversation as a means of improving the cognitive stimulation and language support available to preschool children growing up in disadvantaged circumstances (Madden, O'Hara, & Levenstein, 1984). Similarly, the Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) uses home visits to provide parents with books and parent-child activities during the child's pre-kindergarten and kindergarten years (Baker, Piotrkowski, & Brooks-Gunn, 1999). Each of these programs has shown promise in evaluation studies examining child cognitive and social-emotional school readiness outcomes, but mixed evidence of their effectiveness has also emerged (Baker et al., 1999; Madden et al., 1984). Recruiting and retaining parents in this kind of program has proven to be quite difficult (Welsh et al., in press). It is possible that parent demoralization may undermine these intervention efforts, as parents who feel depressed, overwhelmed, and ineffective may be unable to interact with their children in developmentally facilitative ways, even when offered suggestions regarding how to do so and provided with materials. Further research is needed to explore this possibility and determine whether intervention effects might be strengthened if program components targeting the social-emotional needs and demoralization of parents were added.

There are school readiness programs for parents that focus primarily on parenting practices, which are designed to promote parental confidence and efficacy in their capacity to manage challenging child behaviors. For example, the Incredible Years parenting program, which focuses on parent management training, was adapted for the parents of children attending Head Start (Webster-Stratton, 1998; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001). This program proved effective at decreasing the disruptive behavior problems of children who showed high pretreatment rates of problem behaviors (Reid, Webster-Stratton, & Baydar, 2004) but did not target support for learning, thereby potentially limiting the program's impact on child school readiness. In addition, whereas the Incredible Years program focuses primarily on managing challenging child behaviors, it does not focus on parental feelings about or efficacy in other areas of the parent-child relationship, such as conversation and the provision of emotional support. In general, expanding the design of parent-focused school readiness interventions for at-risk families may benefit from broader goals that take into account the need to both increase parental support for learning and to address parental feelings of depressed mood and low efficacy. Additional intervention research is needed to identify optimal approaches that address these multiple parenting needs.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This study used a multimodal assessment approach, which showed that parent ratings of their own feelings, attitudes, and behaviors were meaningfully related to teachers' views of children's cognitive and social-emotional competence. In addition, this study examined the relationship between parenting and child school readiness in low-SES families and demonstrated that parental demoralization and support for learning significantly and independently affect child school readiness, even after taking into account the lower resources and higher stress experienced by participating families compared to those who are more socio-economically advantaged.

In the context of these strengths, this study also had a number of limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the sample was relatively small and select. The children in the study were identified as low in reading readiness at school entry and attended schools that served large numbers of disadvantaged students. Such homogeneity would likely attenuate findings, rather than inflate them, but the nature of the sample limits the confidence with which the results may be generalized to other samples. In addition, although the sample was ethnically diverse, some important demographic groups were not represented, most notably those who were learning English as a second language. It remains unclear whether the results found in this study would generalize to immigrant or other English language learning families. However, in other studies using somewhat different samples, similar patterns have been found (Feder et al., 2009; Watamura, Phillips, Morrissey, McCartney, & Bub, 2011), and the capacity to show that the relations between parenting and child school readiness exist, even in a sample with constrained SES representation, is a strength of this study. Additionally, outcomes of the 117 children in the study were rated by 18 teachers, thus they are not independent of one another.

Another important limitation of our study was the concurrent nature of the data. Because parent and child data were collected simultaneously and at only one time point, we cannot make inferences regarding prediction or direction of effects. While some longitudinal research on parenting and children's school adjustment would suggest that parents' attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors predict children's achievement (Rodriguez et al., 2009; Silvén, Niemi, & Voeten, 2002), other studies highlight the importance of child characteristics such as impulse control and cooperativeness in shaping parent attitudes and parent-child interactions (Anderson, Lytton, & Romney, 1986; Cunningham & Boyle, 2002) and in moderating the impact of parenting on the child's psychosocial outcomes (Blandon, Calkins, & Keane, 2010). It is likely that children's outcomes are frequently the result of complex, transactional interaction patterns that influence one another over time (Sameroff & Chandler, 1975). Replication of findings with longitudinal data and sample sizes large enough to examine interrelations among multiple aspects of both parent and child functioning is needed. Furthermore, parenting dimensions were assessed using parental self-report only. Assessing parenting behaviors and the home ecology (e.g., frequency of learning opportunities, access to parental support) using additional methods would allow stronger tests of this study's findings. Finally, several of our measures were designed for the study, and therefore their psychometric properties are still being tested. Although all but one (parent-child conversations) had good internal consistency, further validation of these measures with other samples is needed.

In sum, this study contributes to the growing literature illuminating the relations among dimensions of parenting and children's school readiness outcomes. The results confirm that the parenting constructs of demoralization and support for learning are both meaningfully related to children's school adjustment and suggest the importance of addressing both parental psychosocial adjustment and provision of supportive learning environments when developing parent-focused school readiness interventions. As we seek to close the persistent achievement gap that limits the potential of young children in poverty, research illuminating the role played by various aspects of parenting on child adjustment is needed, to help inform and refine school readiness interventions.

Contributor Information

Yuko Okado, St. Jude's Children's Research Hospital.

Karen L. Bierman, The Pennsylvania State University

Janet A. Welsh, The Pennsylvania State University

References

- Anderson K, Lytton H, Romney D. Mothers' interactions with normal and conduct-disordered boys: Who affects whom? Developmental Psychology. 1986;22(5):604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Baker AJL, Piotrkowski CS, Brooks-Gunn J. The Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) The Future of Children. 1999;9:116–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CE, Cameron CE, Rimm-Kaufman SE, Grissmer D. Family and sociodemographic predictors of school readiness Among African American boys in Kindergarten. Early Education & Development. 2012;23(6):833–854. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Whipple N. From external regulation to self- regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children's executive functioning. Child Development. 2010;81:326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman K, Torres M, Domitrovich C, Welsh J, Gest S. Behavioral and cognitive readiness for school: Cross-domain associations for children attending Head Start. Social Development. 2008;18(2):305–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of child functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandon AY, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Predicting emotional and social competence during early childhood from toddler risk and maternal behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(1):119–132. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Markman LB. The contribution of parenting to ethnic and racial gaps in school readiness. The Future of Children. 2005;15:139–168. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman LM, Calzada E, Huang K, Kingston S, Dawson-McClure S, Kamboukos D, Rosenfelt A, Schwab A, Petkova E. Promoting effective parenting practices and preventing child behavior problems in school among ethnically diverse families from underserved, urban communities. Child Development. 2011;82:258–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Vernon-Feagans L, Cox M Key Family Life Project Investigators. Cumulative social risk, parenting, and infant development in rural low-income communities. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2008;8:41–69. doi: 10.1080/15295190701830672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Roberts JE, Zeisel SA, Hennon EA, Hooper S. Social risk and protective child, parenting, and child care factors in early elementary school years. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2006;6(1):79–113. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, von Stauffenberg C. Child characteristics and family processes that predict behavioral readiness for school. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Disparities in school readiness: How do families contribute to successful and unsuccessful transitions to school. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2008. pp. 225–258. [Google Scholar]

- Chazan-Cohen R, Raikes H, Brooks-Gunn J, Ayoub C, Pan BA, Kisker EE. Low-income children's school readiness: Parent contributions over the first five years. Early Education and Development. 2009;20(6):958–977. [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle JE. Educational investment, family context, and children's math and reading growth from Kindergarten through third grade. Sociology of Education. 2008;81:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CE, Crosnoe R, Suizzo MA, Pituch KA. Poverty, race, and parental involvement during the transition to elementary school. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31(7):859–883. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E, Davies P. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):73–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Boyle MH. Preschoolers at risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: family, parenting, and behavioral correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(6):555–569. doi: 10.1023/a:1020855429085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBaryshe B. Maternal belief systems: Linchpin in the home reading process. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1995;16(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- DeBaryshe B, Binder J. Development of an instrument for measuring parental beliefs about reading aloud to young children. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1994;78(3):1303–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Dotterer AM, Iruka IU, Pungello E. Parenting, race, and socioeconomic status: Links to school readiness. Family Relations. 2012;61(4):657–670. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond KV, Stipek D. Low-income parents' beliefs about their role in children's academic learning. The Elementary School Journal. 2004;104(3):197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development. 1994;65:296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Dowsett CJ, Claessens A, Magnuson K, Huston AC, Klebanov P. School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(6):1428–1446. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul G. Parent and teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms: Psychometric properties in a community-based sample. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1991;20(3):245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Harold . Family involvement in children's and adolescents' schooling. In: Booth A, Dunn A, editors. Family-school links: How do they affect educational outcomes? Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Feder A, Alonso A, Tang M, Liriano W, Warner V, Pilowsky D. Children of low income depressed mothers: Psychiatric disorders and social adjustment. Depression and anxiety. 2009;26(6):513–520. doi: 10.1002/da.20522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster MA, Lambert R, Abbott-Shim M, McCarty F, Franze S. A model of home learning environment and social risk factors in relation to children's emergent literacy and social outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2005;20(1):13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fox CR, Gelfand DM. Depressed mood, maternal vigilance, and mother- child interaction. Early Development & Parenting. 1994;3:233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Galster GC. The mechanism(s) of neighbourhood effects: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. In: van Ham M, Harris D, Bailey N, Simpson L, Maclennan D, editors. Neighbourhood effects research: New perspectives. London: Springer; 2012. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Harris K. The mechanisms mediating the effects of poverty on children's intellectual development. Demography. 2000;37(4):431–447. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore: Brookes; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. Two factor index of social position. New Haven, CT: : Privately printed; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover-Dempsey KV, Sandler HM. Why Do Parents Become Involved in Their Children's Education? Review of Educational Research. 1997;67(1):3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jones TL, Prinz RJ. Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(3):341–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam CM, Greenberg MT, Bierman KL, Coie JD, Dodge KA, Foster ME. Maternal depressive symptoms and child social preference during the early school years: Mediation by maternal warmth and child emotion regulation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(3):365–377. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9468-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski RA, Stormshak EA, Good RH, Goodman MR. Prevention of substance abuse with rural Head Start children and families: Results of Project STAR. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:511–526. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.16.4s.s11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan KE, Mensah FK. Poverty, family resources and children's early educational attainment: The mediating role of parenting. British Educational Research Journal. 2011;37(2):317–336. [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. Does neighborhood and family poverty affect mothers' parenting, mental health, and social support? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56(2):441–455. [Google Scholar]

- Knitzer J, Theberge S, Johnson K. Reducing maternal depression and its impact on young children: Toward a responsive early childhood policy framework. National Center for Children in Poverty; Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, Miller-Loncar CL. Early maternal And child influences on children's later independent cognitive and social functioning. Child Development. 2000;71:358–375. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Honorado E, Bush NR. Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of effortful control and social competence in preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein P, Levenstein S, Shiminski JA, Stolzberg JE. Long-term impact of a verbal interaction program for at-risk toddlers: An exploratory study of high school outcomes in a replication of the Mother-Child Home Program. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1998;19(2):267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2) 2002:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Burgess SR, Anthony JL. Development of emergent literacy and early reading skills in preschool children: Evidence from a latent-variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:596–613. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan C, Whitehurst G. Relative efficacy of a parent and teacher involvement in a shared-reading intervention for preschool children from low-income backgrounds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1998;13:263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy M, Graczyk P, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Gil J, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Family resources and parenting quality: Links to children's cognitive development across the first 3 years. Child Development. 2008;79(4):1065–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell AM, Gardner F, Wilson MN. Collateral benefits of the Family Check-Up on early childhood school readiness: Indirect effects of parents' positive behavior support. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(6):1737–1752. doi: 10.1037/a0013858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden J, O'Hara JM, Levenstein P. Home again: Effects of the Mother-Child Home Program on mother and child. Child Development. 1984;55:636–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Ryan RM, Brooks-Gunn J. When fathers' supportiveness matters most: Maternal and paternal parenting and children's school readiness. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(2):145–155. doi: 10.1037/a0018073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Acock AC, Morrison FJ. The impact of kindergarten learning-related skills on academic trajectories at the end of elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2006;21:471–490. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott P. National scales of differential learning behaviors among American children and adolescents. School Psychology Review. 1999;28:280–291. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Benner AD, Biesanz JC, Clark SL, Howes C. Family and social risk, and parental investments during the early childhood years as predictors of low-income children's school readiness outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2010;25(4):432–449. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Applications of causally defined direct and indirect effects in mediation analyses using SEM in Mplus. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.statmodel2.com/download/causalmediation.pdf.

- Nord CW, Lennon J, Liu B, Chandler K. Home literacy activities and signs of children's emerging literacy, 1993 and 1999. Washington DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2000. NCES Publication 2000-026. [Google Scholar]

- Petterson SM, Albers AB. Effects of poverty and maternal depression on early child development. Child Development. 2001;72(6):1794–1813. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C, Baydar N. Halting the development of conduct problems in Head Start Children: The effects of parent training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:279–291. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock D, Pollack J. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Class of 1998-99 (ECLS-K): Psychometric Report for Kindergarten through First Grade (NCES-WP-2002-05) Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics; 2002. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/1a/8a/8f.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez ET, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Spellmann ME, Pan BA, Raikes H, Lugo-Gil J. The formative role of home literacy experiences across the first three years of life in children from low-income families. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30(6):677–694. [Google Scholar]

- Romano E, Babchishin L, Pagani LS, Kohen D. School readiness and later achievement: Replication and extension using a nationwide Canadian survey. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(5):995–1007. doi: 10.1037/a0018880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Fauth RC, Brooks-Gunn J. Childhood poverty: Implications for school readiness and early childhood education. In: Spodek B, Saracho ON, editors. Handbook of research on the education of children. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Chandler MJ. Reproductive risk and the continuum of caretaking casualty. Review of Child Development Research. 1975;4:187–244. [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough A. Behavioral patterns of toddlers with speech language delay: The relationship with child, family, and poverty. Dissertations Abstract International. 2001;61:4339. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research. 2006;99(6):323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Senechal M. Testing the Home Literacy Model: parent involvement in kindergarten is differentially related to grade 4 reading comprehension, fluency, spelling, and reading for pleasure. Scientific Studies on Reading. 2006;10:59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Silvén M, Niemi P, Voeten MJM. Do maternal interaction and early language predict phonological awareness in 3-to 4-year-olds? Cognitive development. 2002;17(1):1133–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Snow K, Burns MS, Griffin P, editors. Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, McMahon RJ, Lengua LJ CPPRG. Parenting Practices and Child Disruptive Behavior Problems in Early Elementary School. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2000;29:17–29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayhorn J, Weidman C. A parent practices scale and its relation to parent and child mental health. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27(5):613–618. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198809000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J, Wilkins A, Dallaire J, Sandler H, Hoover-Dempsey K. Parental Involvement: Model Revision through Scale Development. The Elementary School Journal. 2005;106(2):85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Watamura SE, Phillips DA, Morrissey TW, McCartney K, Bub K. Double jeopardy: Poorer social-emotional outcomes for children in the NICHD SECCYD experiencing home and child-care environments that confer risk. Child Development. 2011;82(1):48–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: Strengthening parenting competencies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:715–730. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Hammond M. Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:283–302. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JA, Bierman KL, Mathis ET. Parenting programs the promote school readiness. In: Boivin M, Bierman KL, editors. Promoting school readiness and early learning: Implications of developmental research for practice. New York, NY: Guilford; 2014. pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Wright C, George T, Burke R, Gelfand D, Teti D. Early maternal depression and children. Child Study Journal. 2000;30:153–168. [Google Scholar]