Abstract

Intermediary metabolism generates substrates for chromatin modification, enabling potential coupling of metabolic and epigenetic states. Here, we identify such a network as a major component of oncogenic transformation downstream of the LKB1/STK11 tumour suppressor, an integrator of nutrient availability, metabolism and growth. By developing genetically engineered mouse models and primary pancreatic epithelial cells and employing transcriptional, proteomics, and metabolic analyses, we find that oncogenic cooperation between LKB1 loss and KRAS activation is fueled by pronounced mTOR-dependent induction of the serine-glycine-one carbon pathway coupled to S-adenosylmethionine generation. In concert, DNA methyltransferases are upregulated, leading to elevation in DNA methylation, with particular enrichment at retrotransposon elements associated with their transcriptional silencing. Correspondingly, LKB1 deficiency sensitizes cells and tumours to inhibition of serine biosynthesis and DNA methylation. Thus, we define a hypermetabolic state that incites changes in the epigenetic landscape to support tumourigenic growth of LKB1-mutant cells, while resulting in novel therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Keywords: LKB1, tumour suppression, cancer metabolism, glucose, serine, one-carbon pathway, DNA methylation, epigenetics, therapeutics

Introduction

Substrates and inhibitors of chromatin-modifying enzymes are generated in intermediary metabolism, hence, changes in nutrient availability and utilization can influence epigenetic regulation1,2. Importantly, recent studies indicate that the interplay between metabolism and epigenetics can serve as a programmed switch in cell states. For example, mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation is promoted by succinate-mediated inhibition of histone demethylases (HDMs) and TET DNA demethylases3, or by decreased S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) levels leading to loss of histone H3K4 methylation4. Moreover, aberrant metabolic activity can produce pathologic effects by altering chromatin regulation. Most notably, mutations in the genes encoding the IDH1/2 enzymes lead to the generation of 2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits HDMs and TETs, thereby altering DNA and histone methylation – changes that have been implicated in overriding cell differentiation and promoting tumorigenesis5. Whether this paradigm extends more generally to other oncogenic mutations remains an open question with implications for understanding cancer pathogenesis and and developing improved treatments. Here, we demonstrate that dynamic exchange between metabolism and chromatin regulation contributes to pancreatic tumorigenesis driven by mutation of the LKB1 serine-threonine kinase.

LKB1 is mutationally inactivated in a range of sporadic cancers, including pancreatic carcinomas6–8. Additionally, germline mutations in LKB1 cause Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, consisting of gastrointestinal (GI) polyps and high incidence of GI tract carcinomas (e.g. ~100-fold increase in pancreatic cancer)9,10. Cancers with LKB1 mutations tend to exhibit aggressive clinical features and differential therapeutic sensitivity11–14. LKB1 directly activates a family of 14 kinases related to AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), many of which are coupled to nutrient sensing and broadly reprogram cell metabolism15. Thus, metabolic rewiring is thought to be a driver of tumorigenesis following LKB1 loss. We now identify an LKB1-regulated program linking metabolic alterations to control of the epigenome that is involved in malignant growth. These studies provide evidence of a more general role of coupled metabolic and epigenetic states in cancer pathogenesis and suggest novel therapeutic strategies targeting these intersecting processes.

RESULTS

Synergy between LKB1 and KRAS mutations

LKB1 inactivation frequently coincides with mutations in the RAS-RAF pathway in human cancers and these genetic alterations cooperate to drive tumorigenesis in genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs)6,11,14,16. We examined the interactions between oncogenic KRASG12D and deletion of LKB1 in the adult pancreatic ducts using a tamoxifen-inducible GEMM (Extended Data Figure 1a). The combined alterations resulted in pancreatic cancers by 20–25 weeks, while the individual mutations had no pathologic effects at this age (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Figure 1b). To investigate the mechanisms of tumourigenesis, we isolated primary pancreatic ductal epithelial cells from mice with conditional KRASG12D and LKB1 alleles (N=2 lines/genotype) and transduced them with adenoviruses expressing Cre and/or Flp recombinase to generate KRASG12D/+, LKB1−/−, KRASG12D/+;LKB1−/− cells (K, L and KL cells, respectively) as well as wild type (WT) parental lines (Extended Data Figure 1c). Only KL cells were tumourigenic following injection into SCID mice or growth in soft agar, and tumourigenicity was blocked by WT LKB1 restoration (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Figure 1d–f). In vitro, KL cells showed increased proliferation relative to K cells, and both were greater than WT and L cells (Extended Data Figure 1g–j). Thus, primary ductal cells provide a tractable in vitro system to study mechanisms of epithelial cell transformation arising from LKB1 inactivation.

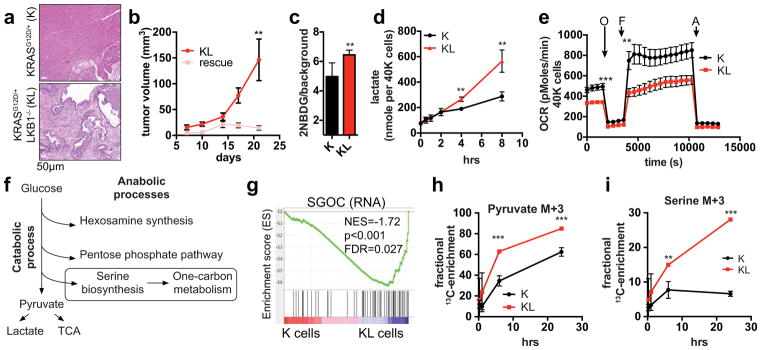

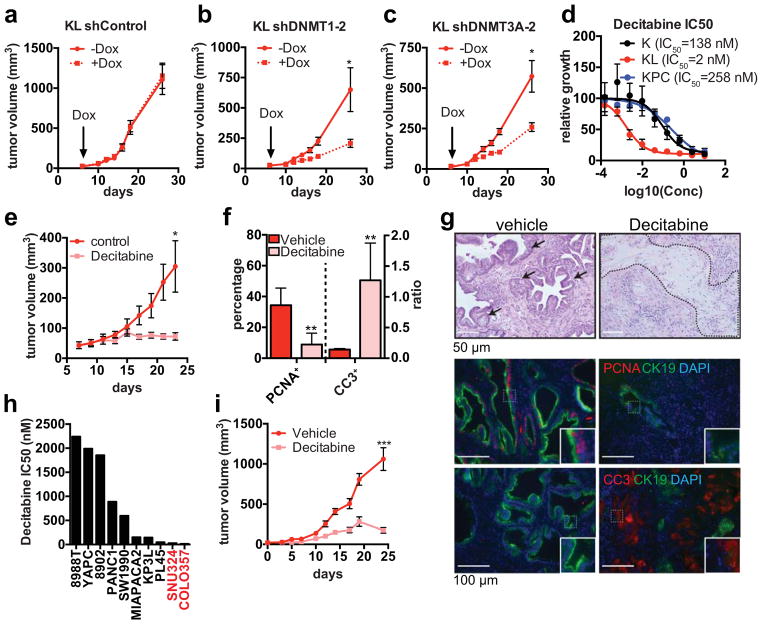

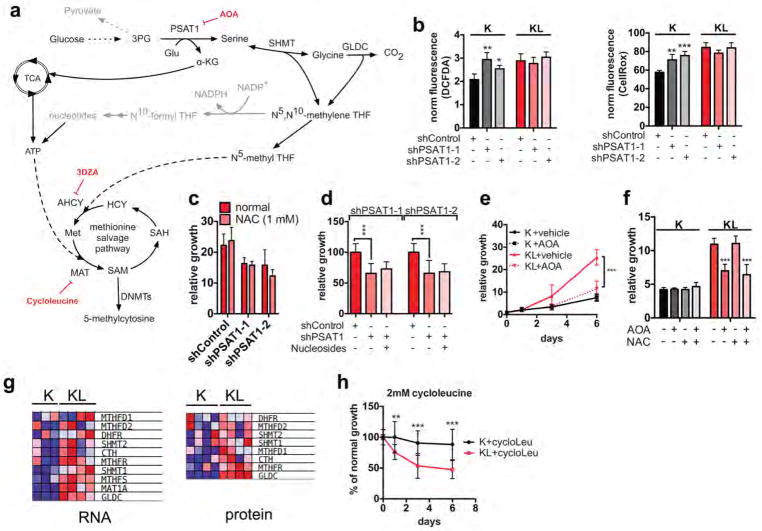

Figure 1. LKB1 inactivation synergizes with KRASG12D to potentiate glycolysis, serine metabolism, and tumourigenesis.

a. Representative pancreas histology of the indicated genotypes of mice at 20–25-weeks (n=4/genotype). b, Subcutaneous tumour growth of KL cells expressing empty vector (KL) or LKB1 (rescue) (n=8/group). c, d, Ductal cells tested for glucose uptake (c) (n=6, independent replicates), and (d) lactate secretion (n=3). e, Oxygen consumption rates in K and KL cells under nutrient replete conditions (n=21). f, Fates of glycolytic intermediates. g, GSEA showing enrichment of serine/glycine/one-carbon network18 (K cells, n=3; KL cells, n=4). NES=Normalized Enrichment Score. h, i, Isotopomer abundance of U13C-glucose-derived M+3 pyruvate (h) or serine (i) (n=3, biological replicates). Data pooled from three (e) or representative of two (d) experiments. Error bars: s.e.m. (b), s.d. (c,d,g,h). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Focusing on the metabolic alterations provoked by loss of LKB1, we found that KL cells exhibited an ~30% increase in glucose uptake compared to K cells, and showed marked elevations in the GLUT1 transporter and in ATP levels (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Figure 1k, l). Lactate levels were elevated, whereas oxygen consumption and citrate levels were reduced (Fig. 1d, e, Extended Data Figure 1m). Moreover, KL cells showed heightened sensitivity to acute glucose deprivation and to inhibition of glycolysis using the glucose analogue, 2-deoxyglucose, the PDK inhibitor, dichloroacetate, or the LDH inhibitor, galloflavin (Extended Data Figure 1n–q). Importantly, neither KRASG12D nor LKB1 inactivation alone promoted significant alterations in glucose metabolism (Extended Data Figure 1r–t). Thus, these genetic lesions acted synergistically to potentiate glycolysis, while rendering cells highly dependent on glucose availability.

These data suggested that an increased supply of glycolytic intermediates was available for anabolic processes to support the growth of KL cells (Fig. 1f). Notably gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of RNA-sequencing and quantitative proteomics17 data indicated that KL cells are enriched for glycolytic enzymes as well as for networks that connect glycolytic intermediates to one-carbon metabolism, with serine-glycine-threonine and folate metabolism scoring highly among the induced pathways (Supplementary Data Table 1). There was a particularly striking enrichment of a 64-gene signature defining the entire serine-glycine-one carbon (SGOC) network18, indicating strong coordinate activation of these pathways (Fig. 1g, Extended Data Figure 2a). Accordingly, the use of uniformly carbon-13-labelled (U13C-)-glucose demonstrated that KL cells have augmented production of glucose-derived pyruvate and lactate, and an even more pronounced increase in serine and glycine biosynthesis rates, without changes in total levels of these amino acids (Fig. 1h, i, Extended Data Figure 2b–d).

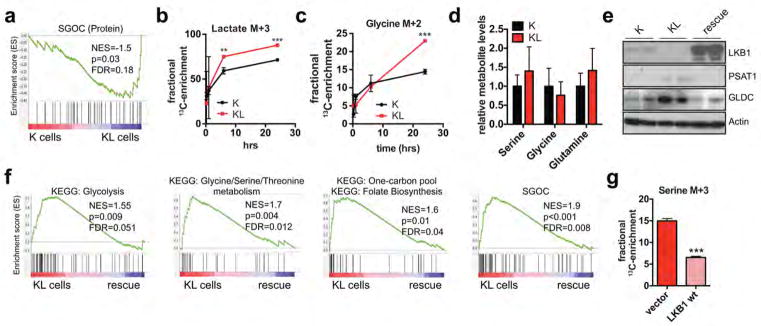

Serine pathway dependence of KL cells

Multiple serine pathway enzymes were upregulated in KL cells (i.e. PSAT1, PSPH, SHMT1 and SHMT2), whereas restoration of LKB1 reversed these changes, broadly suppressed the entire SGOC network, and reduced serine biosynthesis (Fig. 2a, b, Extended Data Figure 2e–g). PSAT1 catalyzes the transamination of 3-phospho-hydroxy-pyruvate (3PHP) to 3-phosphoserine (3PS), with glutamate as the nitrogen donor and a-ketoglutarate (a-KG) as a secondary product (Fig. 2a). Consistent with elevated PSAT1 activity, 15N-Glutamine labeling revealed a marked increase in nitrogen incorporation into serine and glycine in KL cells (Fig. 2c). Thus, LKB1 restrains serine metabolism.

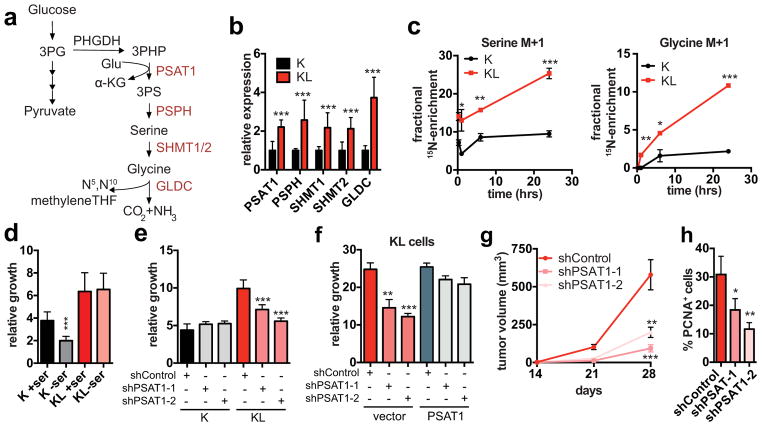

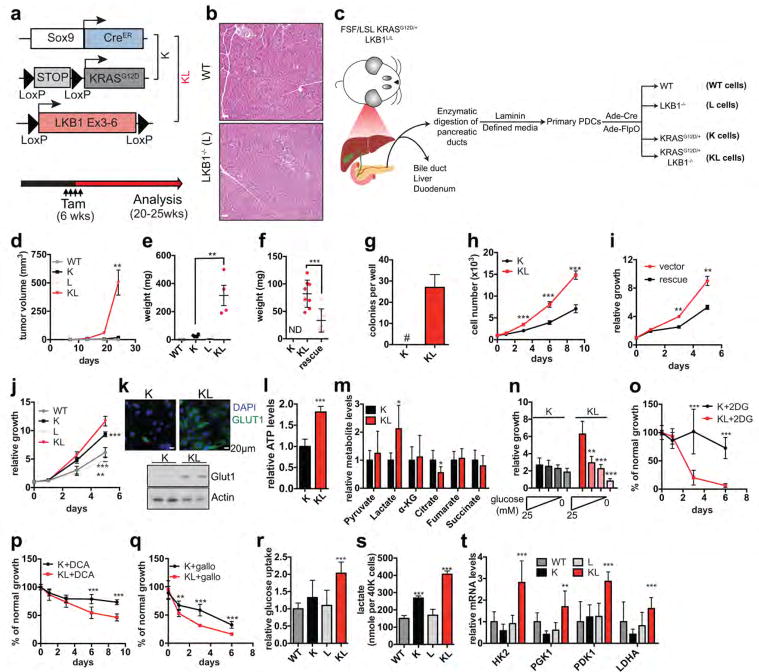

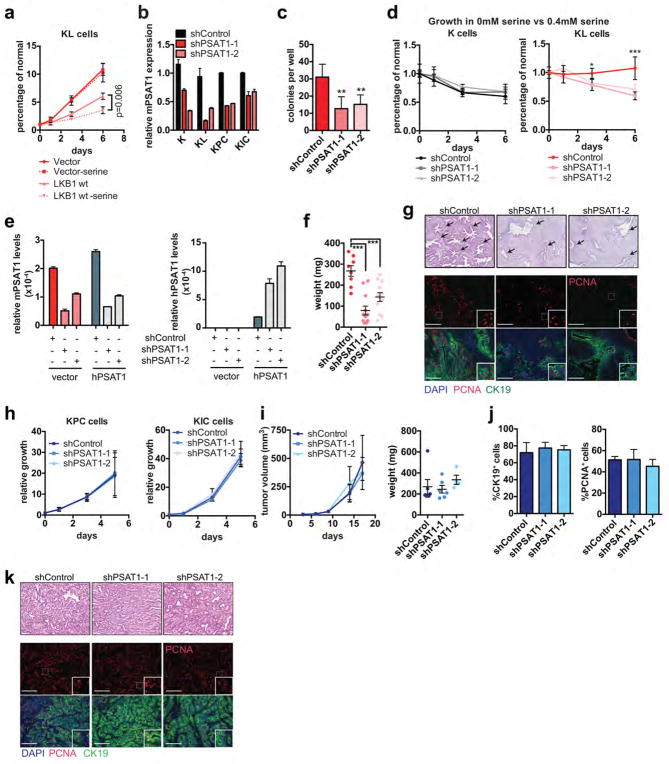

Figure 2. Activation of de novo serine biosynthesis supports growth of LKB1-deficient cells.

a, Serine biosynthesis pathway. Red: upregulated in KL cells. b, Serine pathway gene expression (n=8/genotype). c, Isotopomer abundance of 15N-glutamine-derived M+1 serine and glycine (n=3, biological replicates). d, e, Three-day growth of ductal cells (d) cultured +/− 0.4 mM serine (n=20) or (e) transduced with the indicated shRNAs (n=6). f, Six-day proliferation of KL cells transduced with the indicated shRNAs and expression constructs (n=3). g, Subcutaneous tumour growth of KL cells transduced with the indicated shRNAs (n=12 tumours/group). h, Proportion of CK19+ tumors cells that are PCNA+ (shControl n=4, shPSAT1-1 n=4, shPSAT1-2 n=3, representative tumours). Data pooled from four (b) or representative of two (e, f) or four (d) experiments. Error bars: s.d. (b–f), s.e.m. (g, h). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Accordingly, KL cells were unaffected by culturing in serine-free media, whereas K cells showed a ~40% decrease in proliferation as did KL cells with LKB1 re-expression (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Figure 3a). On the other hand, KL cells were specifically sensitive to PSAT1 knockdown, exhibiting reduced proliferation in normal media, restored dependency on exogenous serine, and impaired colony formation in soft agar (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Figure 3b–d). Introduction of shRNA-resistant human PSAT1 cDNA rescued these phenotypes (Fig. 2f, Extended Data Figure 3e). Moreover, PSAT1 knockdown strongly inhibited the subcutaneous tumour growth by KL cells (Fig. 2g, h, Extended Data Figure 3f, g). Notably, PSAT1 knockdown had no effect on the proliferation or tumourigenicity of cell lines from pancreatic cancer GEMMs with WT LKB1 (KRASG12D-p53 null: KPC and KRASG12D-CDKN2A null: KIC)19 — further linking these effects to LKB1 loss rather than being secondary to high proliferation rates (Extended Data Figure 3b, h–k). Thus, increased serine biosynthesis pathway activity is required to drive oncogenic transformation in KL cells.

Serine pathway fuels DNA methylation

The serine biosynthesis pathway can fuel a range of anabolic processes, including generation of N5, N10-methylene-Tetrahydrofolate (THF) that supports NADPH production and redox homeostasis, as well as nucleotide biosynthesis20. PSAT1 knockdown failed to increase ROS levels in KL cells and, correspondingly, proliferation was not restored by the ROS scavenger, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), nor by nucleosides supplementation (Extended Data Figure 4a–d). Similar results were obtained with treatment with aminooxyacetate (AOA), an inhibitor of PSAT1 and other aminotransferases (Extended Data Figure 4e, f). Thus, the requirement of KL cells for PSAT1 appears to be independent of roles in redox homeostasis or maintenance of nucleoside pools.

Alternatively, serine metabolism can fuel the methionine salvage pathway (Fig. 3a), which is the main mechanism producing the methyl donor SAM 21,22. Notably, multiple enzymes that channel serine metabolism intermediates into the methionine salvage pathway and that contribute to SAM biosynthesis were upregulated in KL cells (Extended Figure 4g). Accordingly, PSAT1 knockdown reduced SAM levels in KL cells but not in K cells (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, SAM supplementation mitigated the proliferation defects caused by PSAT1 ablation in KL cells (Fig. 3c). Conversely, suppression of SAM biosynthesis by inhibition of S-adenosyl-homocysteine-hydrolase (SAH) with 3-Deazaadenosine (3DZA), or methionine-adenosyl-transferase (MAT) with cycloleucine, slowed the growth of KL cells, whereas K cells remained unaffected (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Figure 4h). Thus, activation of de novo serine biosynthesis contributes to SAM production to support growth of LKB1-deficient cells, possibly by providing active methyl groups in the form of N5-methyl-THF, or by promoting ATP generation (e.g. via PSAT1-dependent TCA cycle anaplerosis)22,23.

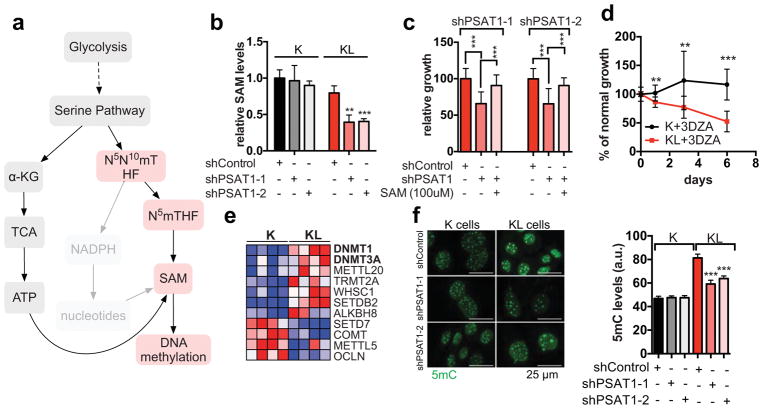

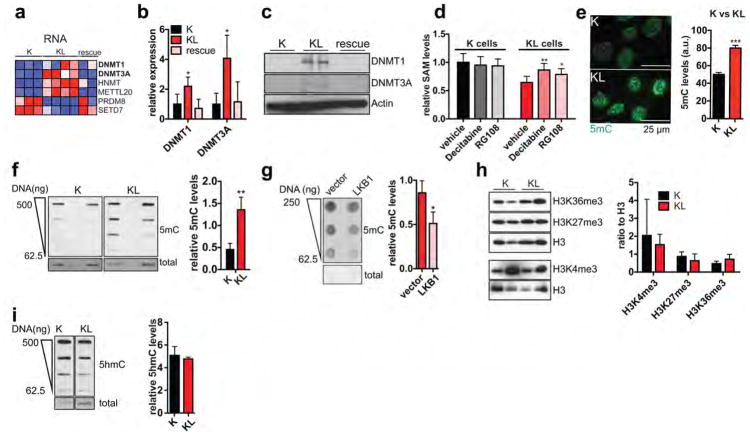

Figure 3. Activation of the SGOC network promotes DNA methylation in LKB1-deficient cells.

a, SGOC network. Red: enzymatic inhibitors. b, SAM levels in ductal cells transduced with the indicated shRNAs (n=4). c, Three-day growth of KL cells +/− SAM-supplementation or PSAT1 knockdown (n=16). d, Proliferation of ductal cells treated with 3-DZA (n=12). e, Heatmap of differentially regulated SAM-utilizing enzymes (proteomics). f, 5mC in ductal cells (77–177 cells). Data pooled from two (c, d, f) or representative of two (b) experiments. Error bars: s.d. (b–d), s.e.m. (f). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

SAM is the substrate for methylation of lipids, DNA, RNA, metabolites and proteins. Examination of our RNA-seq and proteomics datasets for the expression of the 183 annotated SAM-utilizing methyltransferase enzymes revealed significant enrichment of the DNA methyltransferases DNMT1 and DNMT3A in KL cells, while few other changes were noted overall (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Figure 5a, Supplementary Data Table 2). qPCR and immunoblot analyses verified the regulation of expression of these enzymes by LKB1 (Extended Data Figure 5b, c). Importantly, inhibition of DNA methylation using 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine (Decitabine) or the non-nucleoside DNMT inhibitor, RG108, promoted SAM accumulation in KL cells but not in K cells (Extended Data Figure 5d), suggesting that DNMTs are major SAM-utilizing enzymes in the context of LKB1-deficiency.

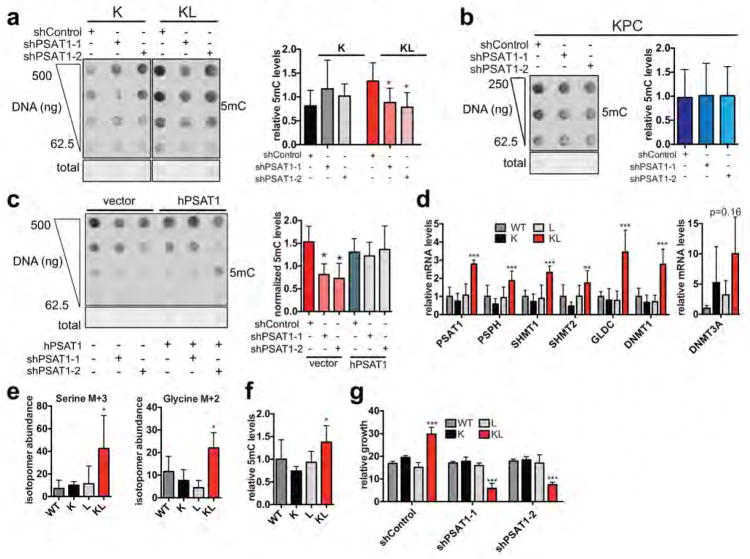

Accordingly, immunofluorescence and DNA dot blot analysis demonstrated that KL cells had a significant increase in 5-methylcytosine (5mC) as compared to K cells, an effect that was reversed by LKB1 rescue (Extended Data Figure 5e–g). By contrast, there were no consistent changes in global levels of a series of histone methylation marks, in 5-hydroxy-methylcytosine, or in N6-methyladenosine (Extended Data Figure 5h–j and data not shown). Notably, PSAT1 knockdown suppressed DNA methylation in KL cells — which was rescued using shRNA-resistant PSAT1 cDNA, while K and KPC controls were unaffected. (Fig. 3f, Extended Data Figure 6a–c). Comparison of all four genotypes using our set of isogenic ductal cells confirmed that serine pathway activity and DNA methylation were specifically potentiated upon dual KRASG12D expression and LKB1 loss (Extended data Figure 6d–g).

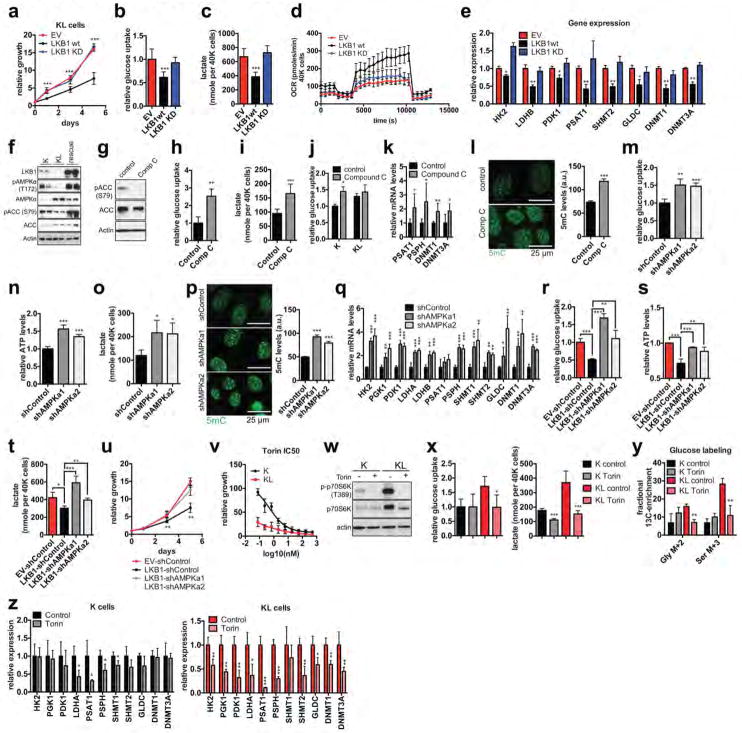

The expression of a kinase-dead (KD) LKB1 mutant confirmed that the key transcriptional and metabolic circuits activated in KL cells were due to loss of LKB1 kinase activity (Extended Data Figure 7a–e). Accordingly, KL cells showed reduced activity of AMPK, an important target of the LKB1 kinase, and consequent activation of -mTOR complex I (mTORC1) (Extended Data Figure 7f, w). Moreover, in K cells, AMPK suppression — using the small molecule inhibitor, Dorsomorphin (Compound C), or shRNAs targeting AMPKa1 or AMPKa2 — increased each of the metabolic and gene expression parameters and upregulated global DNA methylation levels, mimicking the effects of LKB1 loss (Extended Data Figure 7g–q). Additionally, AMPK silencing blocked the effects of LKB1 re-expression on the growth and metabolic properties of KL cells (Extended Data Figure 7r–u). Finally, KL cells were hypersensitive to mTOR inhibition using Torin 1, which suppressed the metabolic and transcriptional changes (Extended Data Figure 7v–z). Thus, deregulation of AMPK-mTORC1 signaling contributes to the altered metabolic and epigenetic network in KL cells.

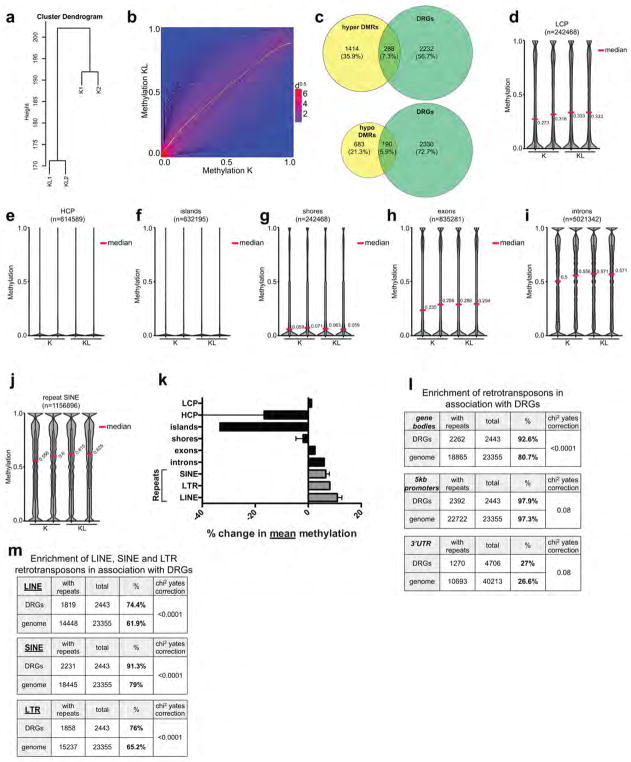

LKB1 loss silences retrotransposons

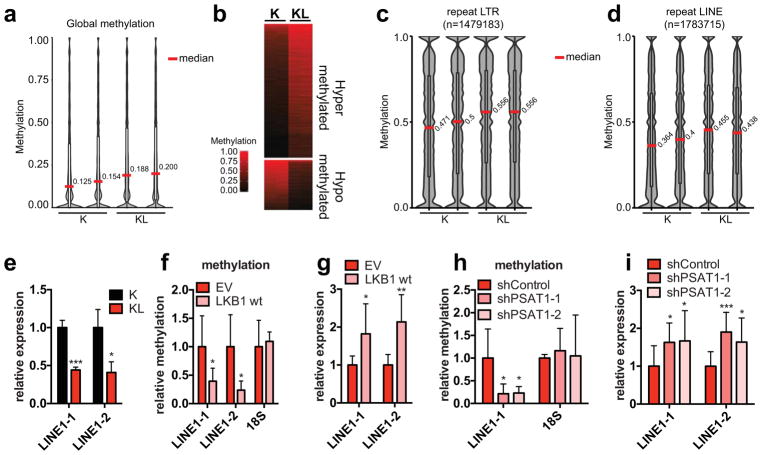

DNA methylation can contribute to transcriptional regulation and maintenance of genomic stability24. We mapped methylation changes by conducting whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) of K and KL cells (two independently-derived lines/genotype). The data demonstrated a marked increase in mean CpG methylation in KL cells (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Figure 8a). Comparison of methylation levels at non-repetitive 100 bp tiles revealed 3395 hypermethylated and 1270 hypomethylated regions in KL cells (FDR <0.05, methylation difference >0.1) (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Figure 8b). However, the genes associated with differentially methylated regions had only modest overlap with those showing differential expression, suggesting that methylation of these elements may not prominently affect transcriptional regulation (Extended Data Figure 8c). Thus, we focused on the repetitive portion of the genome. Notably, methylation in KL cells was particularly enriched at retrotransposon repeats (LTRs, LINEs and SINEs) compared to non-repeat elements (promoters, CpG islands and shores, introns) (Fig. 4c, d, Extended Data Figure 8d–k). These elements comprise a large proportion of the genome, have promoters that can be actively transcribed when unmethylated, and can influence regulation of host genes 25. Consistent with a functional role for the observed retrotransposon methylation, KL cells had a >50% reduction in LINE-1 expression compared to K cells (Fig. 4e). Moreover, restoration of LKB1 suppressed LINE-1 methylation, as determined by 5mC-DNA immunoprecipitation-PCR analysis (meDIP-qPCR), and led to an ~2-fold upregulation of LINE-1 transcript expression (Fig. 4f, g). Importantly, PSAT1 knockdown also reduced LINE-1 methylation and induced its expression in KL cells (Fig. 4h, i), indicating that increased serine metabolism supports retrotransposon methylation and transcriptional silencing downstream of LKB1 loss.

Figure 4. The LKB1-PSAT1 pathway controls methylation and expression of retrotransposons.

a, Distribution of methylation levels in ductal cells. Median values are indicated. b, Heatmap of differentially methylated tiles. c, d, Distribution of methylation levels in LINE1 (c) and LTR (d) repeats. e, Expression of LINE1 in ductal cells, tested using two independent primer sets (n=3). f, g, KL cells transduced with EV or LKB1 assessed for (f) methylation of LINE1 and 18S (n=6, LINE1-1 and 18S; n=4, LINE1-2), and (g) LINE1 expression (n=6). h, I, KL cells transduced with the indicated shRNAs were assessed for (h) LINE1 and 18S methylation (n=6) and (i) LINE1 expression (n=10). Data pooled from two (f, h) or representative of (e, g, i) two experiments. Error bars: s.d. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Since retrotransposons can function as important modulators of host gene expression25, we explored the correlation between differentially expressed genes in K versus KL cells and the presence of linked retrotransposons. We observed a significant enrichment for retrotransposon elements in the gene bodies of differentially expressed genes as compared to the distribution of these elements across all genes (Extended Data Figure 8l, m). By contrast, minimal enrichment was observed when promoter regions were considered. Such specificity is notable considering evidence that intragenic methylation (including repeat methylation) can modify activity of linked promoters and affect RNA processing25,26. Thus, the LKB1-SGOC pathway alters the epigenetic landscape, acting to dynamically regulate retrotransposon methylation and transcriptional activity, changes that appear associated with differences in host gene transcription.

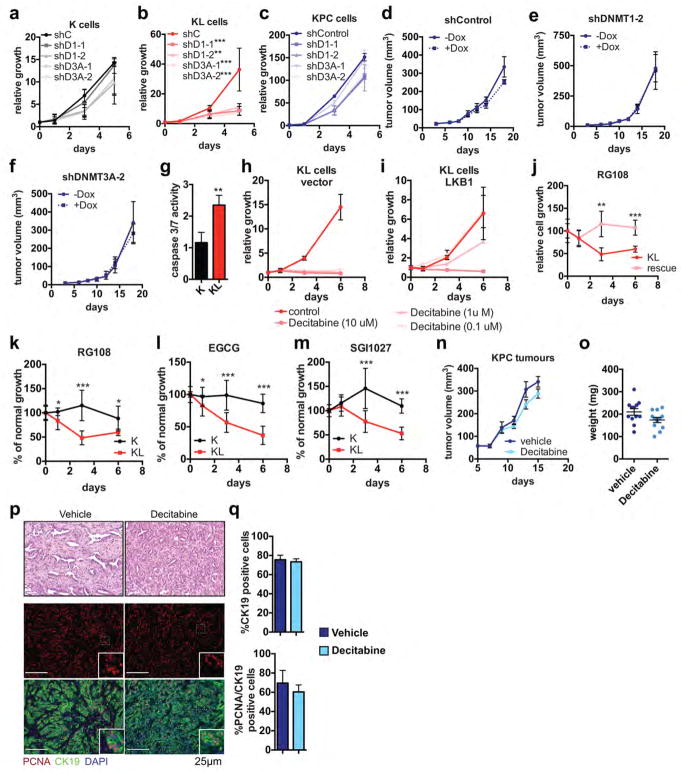

KL cells are sensitive to DNMTi

Consistent with the functional relevance of increased DNA methylation, KL cells were sensitive to shRNA-mediated knockdown of DNMT1 or DNMT3A, whereas K or KPC cells remained largely unaffected (Extended Data Figure 9a–c). Similar specific sensitivity of KL cells was observed in vivo using doxcycline (dox)-inducible shRNAs to acutely deplete DNMT1 or DNMT3 (or shGFP control) once subcutaneous tumours reached 50 mm3 in size (Fig. 5a–c, Extended Data Figure 9d–f). These data indicate that inhibition of DNA methylation is a potential vulnerability of KL cells. Indeed, KL cells were hypersensitive to the clinically approved DNMT inhibitor (DNMTi), Decitabine, as compared to K and KPC cell lines (IC50 KL: 2 nM, K:138 nM, KPC: 258 nM) (Fig. 5d, Extended Data Figure 9g–i). Similar results were obtained using additional DNMTi’s (RG108, EGCG and SGI1027) (Extended Data Figure 9j–m). Importantly, decitabine treatment caused striking regression of subcutaneous KL tumours, associated with necrosis, hyalinization, replacement of tumor glands with fibrosis, decreased tumour cell proliferation, and pronounced apoptosis (Fig. 5e–g). By contrast, KPC xenografts were unaffected by decitabine (Extended Data Figure 9n–q). Thus, LKB1 deficiency confers specific hypersensitivity to inhibition of DNA methylation in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 5. LKB1 deficiency confers hypersensitivity to DNA methylation inhibitors.

a–c, Volume of subcutaneous tumours derived from KL cells transduced with Dox-inducible shRNAs (n=6 tumours/condition). d, Decitabine IC50 for K, KL or KPC cells (n=4). e–g, Decitabine treatment of KL xenografts (n=20 tumours/condition). e, Tumour growth. f, Proportion of CK19+ tumor cells that are PCNA+ (n=4 representative tumours), and ratio of cleaved-caspase 3 (CC3) to DAPI staining (n=4 representative tumours). g, H&E staining of representative tumours (top; arrows: tumor glands, dotted line: hyalinization), and staining for the indicated markers (quantified in (f)). Insets: threefold magnification. h. Decitabine IC50 in human pancreatic cancer cell lines (red: LKB1 mutant, black: LKB1 wt) i, Growth of COLO357 xenografts treated with decitabine (1 mg/kg) or vehicle (n=6/group). Data pooled from three (h) or representative of two (d) experiments. Error bars: s.e.m. (a–c, i), s.d. (d–f). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

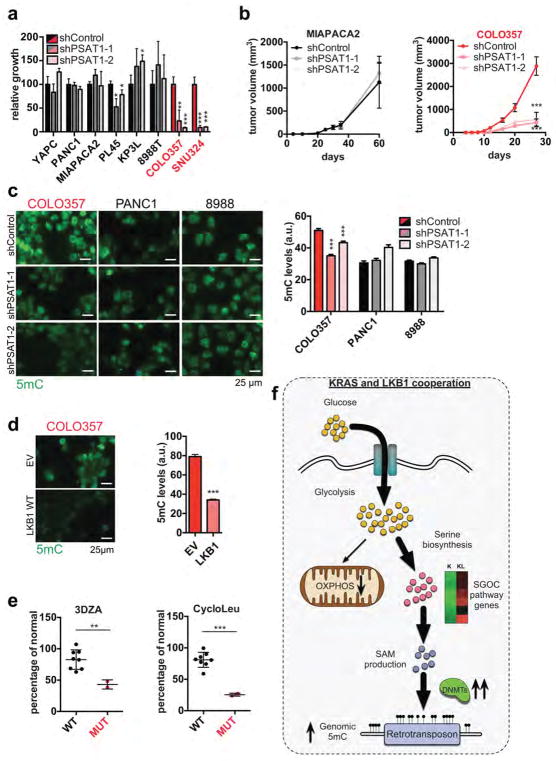

Available human LKB1 mutant pancreatic cancer cell lines (COLO357 and SNU324) showed similar vulnerabilities. They exhibited 70–90% inhibition of proliferation following PSAT1 knockdown, whereas a set of LKB1 WT pancreatic cancer lines showed modest response (Extended Data Figure 10a), consistent with prior results27 in LKB1 WT lines. PSAT1 inactivation also inhibited the growth of LKB1 mutant COLO357 xenografts but not LKB1 WT MIAPACA2 xenografts (Extended Data Figure 10b). Moreover, LKB1 restoration or PSAT1 silencing decreased global methylation in COLO357 cells but not in PANC1 or PATU-8988T (Extended Data Figure 10c, d). LKB1 mutant lines also exhibited increased response to decitabine in vitro and in vivo, and to the methionine salvage pathway inhibitors, 3DZA and cycloleucine (Fig. 5h, I, Extended Data Figure 10e). Thus, both murine and human LKB1 mutant pancreatic tumour cells are sensitized to inhibition of the serine pathway and to DNMT inhibition.

Discussion

In summary, we have defined a metabolic state central to tumourigenesis resulting from LKB1 loss in which glucose and glutamine-derived intermediates are channeled toward the SGOC network leading to increased DNA methylation (Extended Data Figure 10f). Such interplay between metabolic control and epigenetic reprogramming has been proposed as a key mechanism for cancer development in the context of mutations in metabolic enzymes1,2,5. The present work provides evidence of a broader role of metabolic and epigenetic crosstalk in cancer pathogenesis, revealing that LKB1 mutant pancreatic cancer cells have a marked dependency on pathways linking glycolysis, serine metabolism and DNA methylation.

It appears likely that the influence of aberrant metabolism on epigenetics contributes to cancer in the context of other oncogenic mutations. For instance, PI3K/AKT signaling controls acetyl-CoA metabolism to support histone acetylation and regulate growth promoting genes28. Numerous oncogenic pathways rewire metabolism, and the circuits that are activated vary widely, with different genetic lesions favoring distinct fates of glucose, glutamine, fatty acids, and other nutrients. Thus, the resulting alterations in the levels of metabolites affecting chromatin regulation (e.g. NAD+/NADH, FAD, O-linked N-acetylglucosamine, free fatty acids, SAM, acetyl-CoA) may be fundamental to cancer-promotion. Varying conditions in the tumour microenvironment may alter tumour phenotypes via similar processes 29,30.

The gain in DNA methylation at retrotransposons that we observed in KL cells is notable in light of the emerging view that these abundant repeat elements serve critical roles in host gene regulation25. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that reactivation of silenced retrotransposons may underlie the therapeutic benefit of DNMT inhibition (DNMTi), serving to induce a type I interferon anti-viral defense program31,32. The basis for the widespread differences in response to DNMTi observed in vitro and in the clinic remains unclear. In this regard, the present studies in KRAS mutant pancreatic ductal cells suggest that LKB1 status is a genetic marker for DNMTi responsiveness. Since repeat element methylation does not strictly correlate with sensitivity to these treatments33, the precise mechanisms of the specific response of KL cells to DNMTi remain to be defined. In this setting, it will be of interest to determine the relative contributions of IFN pathway activation and of modulation of host gene expression. Together our data point to novel therapeutic vulnerabilities in the context of LKB1 mutations, suggesting the potential of using agents targeting nodes of this network in defined patient subsets, although additional studies will be needed to broadly establish these associations in human cancers.

The present data and other recent reports highlight the importance of deregulation of the serine biosynthesis in cancer, which can result from amplification of genes encoding pathway enzymes23,34 or their transcriptional activation downstream of oncogenic drivers, including NRF235, c-MYC36–38, and mTOR39. Serine metabolism can fuel a diversity of biosynthetic pathways as well as contribute to energy production. Correspondingly, its functional role in aberrant growth appears context dependent, relating variously to supporting nucleotide biosynthesis, NADPH production, TCA cycle anaplerosis, as well as DNA or histone methylation. These findings underscore the emerging interest in developing new approaches to targeting components of the SGOC network as cancer therapeutics.

Materials

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: CK19 (TROMA-III) from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa; β-actin (A5316) and anti-GLDC (HPA002318) from Sigma-Aldrich; Glut1 (ab652) from Abcam; PCNA (13110), Cleaved caspase 3 (9579), DNMT1 (5032), DNMT3A (2160), histone H3 (4499), histone 3 trimethyl-lysine 4 (9727), histone 3 trimethyl-lysine 27 (9733) and histone 3 trimethyl-lysine 36 (4909) from Cell Signaling Technology; 5-methylcytosine 33D3 (MABE146) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine HMC-MA01 (MABE317) from Millipore. Laminin (23017-95), 2NBDG (N13195), DCFDA (C6827), CellROX Green (C10444), CyQuant NF (C35006), bovine pituitary extract (13038-14), HBSS, RPMI, DMEM, DMEM:F12, MEM penicillin-streptomycin, pyruvate solution, fetal bovine serum (FBS) Alexa 488 and 568-conjugated secondary antibodies from Life Technologies; nicotinamide (N3376), trypsin inhibitor (T6522), dexamethasone (D4902), S-adenosylmethionine (A2408), 3,3,5-tri-iodo-L-thyronine (91990), oligomycin (75351), antimycin A (A8674), 2-deoxyglucose (D6134), dichloroacetate (347795), collagenase (C7657), glucose (G7528), aminooxyacetate (C13408), N-acetylcysteine (A9165), adenosine (A4036), guanosine (G6264), thymidine (T1895), uridine (U3003), cytidine (C4654), cycloleucine (A48105), cholera toxin (C8052), L-serine (S4500), betaine (61962), dimethylglycine (D1156), tamoxifen (T5148) and methylene blue (M4159) from Sigma; FCCP (0453), decitabine (2624), RG108 (3295), EGCG (4524), Compound C (3093), Torin 1 (4247) and galloflavin (4795) from Tocris; mouse EGF (354001), NuSerum IV (355104), ITS+ Premix (354352) and matrigel (354234) from Corning; SGI1027 (S7276) from Selleckchem; caspase-Glo 3/7 kit (G811A) and Celltiter-Glo kit (G755B) from Promega; 13C-U-Glucose (CLM-1396-1) and 15N-Glutamine (NLM-1016-1) from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc; dispase (165-859) from Roche; lactate assay kit (K607-100) from Biovision Inc; Vectashield with DAPI (H1500) from Vector Laboratories; Bridge-IT SAM assay kit (1-1-1003B) from Medionics; meDIP kit (55009) from Active Motif; 3DZA (9000785) from Cayman Chemicals; Adeno-FlpO (1760) from Vector Biolabs; Adeno-Cre-eGFP from the Viral Vector Core Facility, University of Iowa.

Genetically engineered mouse models

Mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facilities at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). All experiments were conducted under protocol 2005N000148, approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care at MGH. The following mouse strains were used: LSL KRASG12D/+ 1, FSF KRASG12D/+ (Jackson Laboratory, strain #023590), LKB1L/L 2, Sox9-CreER 3. Mice were maintained on a mixed genetic background and each genotype was generated from intercrosses from the same colony. The Sox9-CreER transgene deletes floxed sequences in pancreatic ductal cells following treatment with tamoxifen. To activate CreER, 8 week-old mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 mg/kg tamoxifen dissolved in corn oil every other day for 6 days. Mice were euthanized when criteria for disease burden were reached (including abdominal distension that impeded movement, loss of >15% of body weight, labored breathing, and/or abnormal posture). Both male and female animals were used for these experiments.

Cell Culture

Primary pancreatic ductal epithelial cells were isolated from two LSL-KRASG12D/+, two LSL-KRASG12D/+;LKB1L/L or three FRT-KRASG12D/+;LKB1L/L mice as previously described4 with modifications. In brief, mice were euthanized and the pancreata were rapidly collected, followed by microscopy-assisted removal of the bile duct. Tissues were washed once in PBS, suspended in 3–5 ml of 2 mg/ml collagenase in DMEM:F12 (filter sterilized) and incubated at 37°C for 15 min with rigorous agitation. 7–10 ml of PBS was added to each tube, the homogenate was left to settle for 5 min at room temperature and the supernatant containing mainly acinar cells was discarded. The remaining tissue was transferred in 6 cm plates, mechanically dissociated with blades/scissors, transferred to a new tube, suspended in 2 ml freshly prepared dispase solution (4 mg/ml in PBS, filter sterilized) and incubated at 37°C for 8–10 min with agitation. Dispase was inactivated by addition of 10 ml G solution (sterile HBSS, 0.9 μg/L Glucose, 1X Pen/Strep). To capture the largely intact ductal structures and clear dissociated acinar cells, homogenate was filtered through a 100 μm strainer that retained only the ducts. After washing with G solution, ducts were recovered by inverting the strainer and washing it with 50 ml G solution followed by gently pelleting by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 1 min. Supernatant was aspirated and ducts were washed twice more with 50 ml G solution each time. After the last wash, pellet was suspended in 2 ml trypsin, incubated for 5 min at room temperature then trypsin was inactivated by addition of 10 ml DMEM+10% FBS+1X Pen/Strep. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed twice in ductal media (DMEM:F12, 5 mg/ml Glucose, 1.22 mg/ml nicotinamide, 5 nM 3,3,5-tri-iodo-L-thyronine, 1 μM Dexamethasone, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, 5 ml/L ITS+, 1X Pen/Strep, 0.1 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor, 20 ng/ml mouse EGF, 5% NuSerum IV and 25 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract) and plated. To activate KRAS and/or delete LKB1 in the LSL-KRASG12D/+ and LSL-KRASG12D/+;LKB1L/L cells, cultures were infected with Ad-CreGFP (1–5×106 pfu/ml) leading to K and KL cells (Extended Data Figure 1A). Alternatively, in order to generate all four genotypes (WT, K, L, KL), FRT-KRASG12D/+;LKB1L/L primary ductal cells were infected with Adeno-Cre-eGFP and/or Adeno-FlpO to delete LKB1 or activate KRASG12D respectively, while uninfected cells were used as WT (Extended Data Figure 1A). All pancreatic ductal epithelial cells were routinely maintained in ductal media on laminin-coated plates. KPC and KIC cells murine pancreatic cancer cells were derived from the Pdx1-Cre;KRASG12D/+;p53Lox/+;p16+/− and Pdx1-Cre;KRASG12D/+;CDKN2ALox/+ GEMM, respectively5. Human cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (PANC1, YAPC, 8988T), the Korean Cell Line Bank (SNU324), and Dr. Paul Chiao from MD Anderson Cancer Center (COLO357), and cultured in the following media: PANC1, YAPC, 8988T in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS; COLO357, SNU324 in RPMI with 10% FBS. Status of LKB1 gene was validated by genomic sequencing and western blot analysis. Negative mycoplasma contamination status of all cancer cell lines and primary cells used in the study was established using LookOut Mycoplasma PCR Kit (Sigma, MP0035). STR profiling of all human cell lines was done at the Center for Molecular Therapeutics at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Cell proliferation, IC50 determination, and caspase 3/7 activity assays

For growth assays, cells were plated at a density of 1000 cells per well in black 96-well plates, using 3–4 replicates per time point and/or condition, and allowed to attach overnight. Cell growth was assessed by DNA content measurement using the Cyquant NF kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Day 0 was considered the day after the initial seeding. For the inhibitor studies, the concentration used in each case was as follows: 5 mM 2-deoxyglucose, 5 mM dichloroacetate, 20 μM galloflavin, 250 μM aminooxyacetate, 1 mM N-acetyl-cysteine, 10 μ 3-deazaadenosine, 2 mM cycloleucine, 0.1–10 μ decitabine, 100 μM RG108, 25 μ SGI1027, 10 μM EGCG, 5 μ Compound C, 25 nM Torin. Inhibitor or vehicle in fresh media was administered at day 0 and replenished every 3 days except in the case of decitabine, which was replenished daily due to stability issues. For testing serine dependence, ductal cells were cultured in MEM-based ductal media, with or without 0.4 mM L-serine supplementation. For glucose restriction studies, ductal cells were cultured in modified ductal media based on DMEM without glucose, glutamine or pyruvate. For assessing the ability of metabolites to rescue shPSAT1-induced growth inhibition, duct-media was supplemented with 100 μM S-adenosyl-methionine, 1 mM betaine, 1 mM dimethylglycine, or 1 m nucleoside mixture (1 m each of adenosine, guanosine, thymidine, cytidine and uridine). Soft agar assays were performed as previously described6. For IC50 determination, cells were treated with 0.0015–30 μ decitabine or 0.076–500 nM Torin for 4 days. Apoptosis was measured using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Metabolic measurements

For ATP measurements, cells were plated at a density of 10,000 cells per well in white 96-well plates at 3–4 replicates per condition, and allowed to attach overnight. Media were changed next day and ATP was measured 24 hrs later using the CellTiter Glo kit according the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was normalized to number of cells as measured by DNA content using CyQuant NF. Lactate was measured using the Lactate Colorimetric/Fluorimetric Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorescence was normalized to number of cells as measured by DNA content using CyQuant NF. For glucose uptake, 400,000 cells were treated with 100 μ 2-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)Amino)-2-Deoxyglucose (2NBDG) for 30 min. Cells were then trypsinized and single-cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry. Due to differences in endogenous fluorescence between genotypes under the conditions of the experiment, 2NBDG mediated fluorescence was normalized to that of unlabeled cells. S-adenosyl-methionine levels were measured using the Bridge-IT SAM Fluorescence kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For reactive oxygen species analysis, cells were plated at a density of 10,000 cells per well in black 96-well plates at 3–4 replicates per condition, and allowed to attach overnight. Media were changed next day and ROS levels were measured 24 hrs later using DCFDA or CellROX staining according the manufacturer’s instructions. Oxygen consumption rates were measured in an XF24 Analyzer (Seahorse). In brief, cells were plated in 96-well Seahorse plates at a density of 40,000 cells per well in duct media and were allowed to attach overnight. Media was replenished one hour prior to assay time. The sequential ports of the Seahorse cartridge were loaded with the following: port A, oligomycin, port B, 2-2-[4-(trfluoromethoxy) phenyl]hydrazinylidene]-propanedinitrile (FCCP), port C, antimycin A, each diluted in media. The final concentration of the inhibitors was 4 μM. Oxygen consumption rates were monitored in real time after injection using the XFe Analyzer (Seahorse). For normalization, equal numbers of cells were plated in black 96-well plates and cell numbers were assessed by CyQuant NF.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA decontamination and reverse transcription were performed in two steps from 1 μg of total RNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, #205310) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To test the effectiveness of the gDNA decontamination step, no-reverse-transcriptase control samples were included. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with FastStart Universal SYBR Green (Roche) in a Lightcycler 480 (Roche). PCR reactions were performed in triplicate and the relative amount of cDNA was calculated by the comparative CT method using the 18S ribosomal RNA sequences as a control. Primer sequences:

| MMU-PSAT1-F | TTAGCACCATGGAAGCCACC |

| MMU-PSAT1-R | TGCCGAGTCCTCTGTAGTCT |

| MMU-DNMT1-F | GTCGGACAGTGACACCCTTT |

| MMU-DNMT1-R | TTCGTGAAGTGAGCCGTGAT |

| MMU-DNMT3A-F | GTCATGGGAGGTTCCCTGTG |

| MMU-DNMT3A-R | ATTAGCACCAGCTTGGGACC |

| MMU-PSPH-F | AACTGGTTCTCCCGTCATCG |

| MMU-PSPH-R | CTCTTAAAAGCGCCGAACCG |

| MMU-PGK1_F | TACCTTGCCTGTTGACTT |

| MMU-PGK1_R | TGTCTCCACCACCTATGA |

| MMU-HK2_F | CCAGCTGTTTGACCACATT |

| MMU-HK2_R | TCATTCACCACAGCCACA |

| MMU-PDK1-F | ATCCGTACAGCTGGTGCAAA |

| MMU-PDK1-R | ACCCCGAAGCTCTCCTTGTA |

| MMU-LDHA-F | TGCACTAGCGGTCTCAAAAGA |

| MMU-LDHA-R | TCCATGACGTCAACAAGGGC |

| MMU-GLDC-F | GTGCAAGAGGGTATGTGGCT |

| MMU-GLDC-R | GACATGGTAGGGGCGTGAAA |

| MMU-SHMT1-F | GGAACAGACGTTTACGGCCA |

| MMU-SHMT1-R | GTCTGCCATTGCACTGGTTC |

| MMU-SHMT2-F | ACCCCGGTACTACACCGATA |

| MMU-SHMT2-R | AGACCAGCTGACCACATCTC |

| HSA-PSAT1-F | CAGTTCAGTGCTGTCCCCTT |

| HSA-PSAT1-R | CCAAGCTCCTGTCACCACAT |

| MMU-LINE1-1-F | GTTCCGGGACTCCGACAAAA |

| MMU-LINE1-1-R | AAAAGGGTGCTGCCTCAGAA |

| MMU-LINE1-2-F | TCTGGGGTGAGCTAGAACCT |

| MMU-LINE1-2-R | AGAAGCTCTGTGGCTCTTGC |

| 18S-F | GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT |

| 18S-R | CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG |

SDS-PAGE analysis

Cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, one tablet of EDTA-free protease inhibitors [Roche] per 10 ml). Samples were clarified by centrifugation and protein content measured using BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). 10 μg protein was resolved on 8–15% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). Membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 5% non-fat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T), prior to incubation with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then washed with TBS-T followed by exposure to the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 45 min and visualized on Kodak X-ray film using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Thermo Scientific).

Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (meDIP-PCR)

5-methylcytosine-enriched DNA was purified using the MeDIP assay kit (Active Motif) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The recovered methylated DNA was quantified by real-time PCR using input DNA for normalization. The primers used for the PCR step are as follows:

| MMU-LINE1-1-F | GTTCCGGGACTCCGACAAAA |

| MMU-LINE1-1-R | AAAAGGGTGCTGCCTCAGAA |

| MMU-LINE1-2-F | TCTGGGGTGAGCTAGAACCT |

| MMU-LINE1-2-R | AGAAGCTCTGTGGCTCTTGC |

| 18S-F | GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT |

| 18S-R | CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG |

Xenograft studies

For subcutaneous xenografts, 5 × 105 cells were suspended in a 1:1 mixture of media:matrigel, and injected subcutaneously into the lower flank of NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/J mice (6–10 weeks of age) (purchased from Jackson Laboratories, strain #001303). Tumor size was assessed at indicated time points by caliper measurements of length and width and the volume was calculated according to the formula (length × width2/2). For the decitabine treatment studies, tumours were allowed to grow to ~125 mm3, then mice were randomized into two groups and each group treated intraperitoneally with either decitabine (1 mg/kg in PBS) or vehicle (PBS) three times per week until mice in the vehicle-treated group had to be sacrificed. No mice were excluded from the analysis. For the shDNMT studies, tumors were allowed to grow to ~50 mm3, then mice were randomized into two groups and doxycycline (200 mg/L) added to the water of one of the groups. Water was changed every 3 days. For volume-measurement-experiments were designed to detect a 50% change in tumor size with 80% power and a type I error of 5% using the T-test. All experiments were conducted under protocol 2005N000148 approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care at Massachusetts General Hospital and no tumours exceeded the size allowed by it. Mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facilities. Both male and female animals were used for these experiments.

Statistics

In all cases, results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise specified. Significance was analyzed using 2-tailed Student’s t test, except in the case of Extended Data Figure 8l and m in which the χ2 test was used. Equal variance was assumed and the assumption was not contradicted by the data. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No samples or animals were excluded from analysis and sample size estimates were only used in xenograft experiments (see section Xenograft studies). Histology evaluation was done on a blind fashion. Tumour size measurements were not blinded.

Dot blot analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated with the Blood and Tissue DNA isolation kit (Qiagen) and sheared by passing 20 times through a 28G1/2 U-100 Insulin Syringe (Becton Dickinson). Two-fold serial dilutions of the prepared DNA were prepared in TE and they denatured in 0.4 M NaOH/10 mM EDTA at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by neutralization with an equal volume of cold 2M ammonium acetate (pH 7.0). Denatured DNA samples were spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane using an assembled Bio-Dot apparatus (Bio-Rad) or a PR648 Slot blot manifold (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The membrane was washed with 2 × SSC buffer and DNA was ultraviolet-crosslinked for 10 min. Then the membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h and incubated with anti-5mC antibody overnight. Detection was carried out with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Thermo Scientific). The membrane was subsequently stained with methylene blue to confirm corresponding amounts of DNA for each sample. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ (NIH).

Expression and hairpin constructs

Full length wild type or kinase dead (K78I)7 LKB1/STK11 protein was expressed from a pMSCV vector (blastocidin resistance). Human PSAT1 that is not targeted by hairpins against mouse PSAT1 was obtained from Harvard PlasmidID Database (HsCD00414859). shRNAs were obtained from The Molecular Profiling Laboratory (MPL) at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in partnership with the RNAi Consortium and have the following IDs: mouse PSAT1 TRCN0000346654 (CCATCAGTCCTTGACTACAAA), TRCN0000346659 (ACACTCGGTATTGTTGGAGAT), human PSAT1 TRCN0000035265 (CCAGACAACTATAAGGTGATT), TRCN0000035266 (GCACTCAGTGTTGTTAGAGAT), mouse AMKPa1 TRCN0000220674 (CGTAGTATTGATGATGAGATT), mouse AMPKa2 TRCN0000220717 (CGCCAGTCTTATCACTGCTTT), mouse DNMT1 TRCN0000039024 (GCTGACACTAAGCTGTTTGTA), TRCN0000039027 (CCCGAAGATCAACTCACCAAA) and mouse DNMT3A TRCN0000231273 (CTGCTACATGTGCGGGCATAA) and TRCN0000231275 (ACCACCAGGTCAAACTCTATA). A hairpin against GFP was used as control. Tet-inducible vectors expressing the DNMT1 and DNMT3A hairpins were obtained by annealing oligos corresponding to the constitutive hairpins and cloning them in the Age I/EcoRI site of the pLKO.1 tet-on vector as previously described8.

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

Cells were plated on poly-D-lysine/laminin coated 8-well culture slides (354688, BD Biosciences) at 40,000 cells/well. 12–16 hours later, the slides were rinsed with PBS once and fixed for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT or for 5 min with −20 °C methanol. The slides were rinsed twice with PBS and cells were permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 for 2 min or with 4N HCl for 5mC staining. HCl treated cells were neutralized with 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5 for 10 min in RT. After washing twice with PBS, the slides were incubated with primary antibody in 5% normal goat serum for 1hr at room temperature, rinsed four times with PBS, and incubated with secondary antibody produced in goat (diluted 1:400 in 5% normal goat serum) for 45 min at room temperature in the dark. Slides were mounted on glass slides using Vectashield (See Materials section) and imaged on Nikon ECLIPSE Ni microscope. Tissue samples were fixed overnight in 4% buffered formaldehyde, and then embedded in paraffin and sectioned (5 μm thickness) by the DF/HCC Research Pathology Core. Haematoxylin and eosin staining was performed using standard methods and stained slides were photographed with an Olympus DP72 microscope. For fluorescent immunohistochemistry, unstained slides were baked at 55 °C, deparaffinized in xylene (two treatments, 6 min each), rehydrated sequentially in ethanol (5 min in 100%, 3 min in 95%, 3 min in 75%, and 3 min 40%), and washed for 5 min in 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS (PBST) and 3 min in water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating deparaffinized tissue sections with 3% Hydrogen Peroxide (20 min; Fisher Scientific), rinsed twice with water (3 min) and antigen retrieval was performed by boiling in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (20 min, 95°C, pH 6). Sections were blocked 1 hour in TBS-0.05 % Tween 20–10% Normal Goat Serum (5425, Cell Signaling), and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution as follows: PCNA (1:10,000), Cleaved Caspase 3 (1:150), CK19 (1:50). Specimens were then washed three times for 3 min each in PBST and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies produced in goat (diluted 1:400 in 5% normal goat serum) for 45 min at room temperature in the dark. Slides were mounted on glass slides using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and imaged on a Nikon ECLIPSE Ni microscope. For PCNA staining, fluorescent signal was amplified using the Tyramide Signal Amplification kit (Perkin Elmer) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were processed using ImageJ software. For quantification of proliferation in tumor slides only the epithelial compartment was considered (CK19 positive). 4–6 fields containing 700–1500 cells per field from 4 different tumors in each case were analyzed. For quantitation of cleaved caspase 3 staining, 3–5 fields containing 500–1500 cells per field from 4 different tumours were analyzed. Apoptotic levels were calculated as the ratio of cleaved caspase 3 intensity to DAPI. For 5mC immunofluorescence staining deparafinized TMA slides were permeabilized with 4 N HCl for 1hr at 37°C followed by neutralization with 100mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5 for 10min at RT. Washes, primary and secondary antibody were applied as described above). Slides were mounted using Vectashield without DAPI. For 5mC immunofluorescence 77–889 cells per condition were analyzed. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ (NIH).

Gene Expression Profiling

RNA-sequencing was performed using total RNA isolated in duplicates from 2 independent cell lines from K or KL genotypes or from the two independent KL lines transduced with full length LKB1 cDNA (rescue). RNAseq library-preparation and sequencing were performed by the Tufts University Genomics Core Facility. Data was processed using a standard RNA-seq pipeline that used Tophat29 to align the reads to mm9, and the Cufflinks suite10 to calculate differential expression. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp) of the expression data was used to assess enrichment of the KEGG as well as the SGOC geneset11–13. In all cases, pairwise GSEA was performed by creating ranked lists of genes using the log2 ratio of K to KL or KL to rescue and p-values were obtained by permuting the gene set (1000 permutations). Raw sequencing files can be found under the Superseries record GSE86145 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE86145).

13C-Glucose and 15N-Glutamine tracing

Cells were plated in 10 cm plates at a density of 106 cells/plate and allowed to attach overnight. Next day, they were washed with PBS to remove traces of unlabeled metabolites, then overlayed with ductal media based on DMEM without glucose, pyruvate or glutamine, supplemented with 25 mM regular of 13C-glucose, 2 mM regular or 15N-glutamine and 2 mM pyruvate. At the indicated time points, cells were washed three times with ice cold 0.9% NaCl, then collected by scraping in 50% methanol. After 30 sec vortexing, samples were pelleted and the clarified supernatant was transferred to a new tube. Protein was removed by chloroform extraction. The purified aqueous phase was dried under vacuum. Dessicated metabolites were derivatized as previously described14. In brief, samples were dissolved in 30 μl of 2% methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine (MOX, Pierce) and incubated at 37°C for 1.5 hrs. Further derivatization was achieved by addition of 45 μl of N-Methyl-N-tert-butyldimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA + 1% TBDMSCI, 375934 Sigma) followed by vigorous mixing and incubation at 55°C for 1 hr. Samples were then pulse spun to remove insoluble material. Clarified solutions were transferred to inserts set in brown glass vials and capped prior to being loaded onto the column. Analysis was performed on an Agilent 6890 GC instrument. Samples were loaded onto a 30 m DB-35MS capillary column using helium as the carrier gas that was interfaced to an Agilent 5975B MS. Electron impact (EI) ionization was set at 70 eV. Each sample was injected at 270°C at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. To mobilize metabolites, the GC oven temperature was held at 100°C for 3 min and increased to 300°C at 3.5°C/min for a total run time of approximately 1 hr. For intracellular metabolites, 1 μl of each sample was injected in splitless mode. All analyses were operated in full scan mode while recording a mass to charge ratio (m/z) spectra in the range of 100–650 m/z. Specific metabolite m/z analyzed are available upon request. Fractional enrichments of 13C and 15N labeled metabolites have been corrected for the natural abundance of 13C and 15N using METRAN15–18 and in house scripts written in Matlab. In-house scripts are available upon request. For LC-MS analysis, cells were plated at a density of 500K cells/plate and allowed to attach overnight. Next morning, they were washed with PBS to remove traces of unlabeled metabolites, then overlayed with ductal media based on DMEM without glucose, pyruvate or glutamine, supplemented with 25 mM regular of 13C-glucose, 2 mM regular or 15N-glutamine and 2 mM pyruvate. At the indicated time points, cells were washed three times with ice cold 0.9% NaCl, then collected by scraping in methanol:acetonitrile:water (40:40:20) and cells were lysed by three freeze and thaw cycles (dry-ice bath and room temperature). After 30sec vortexing, samples were pelleted and the clarified supernatant was transferred to a new tube. Fifty microliters of the cleared extract were transferred to inserts set in brown glass vials and capped prior to being loaded onto the column. Samples were loaded by autosampler (FAMOS+) on a capillary (75 μm) 12cm ProntoSil C18 (3 μm, 200 Å, Bischoff) column that was interfaced with a Thermo Exactive MS. Metabolites were eluted applying a gradient of 3%–100% MeOH with tributylamine for ion pairing over 40 min at a flow rate of 150 μl/min using an Agilent 1260 infinity pump. The nanospray ionization source (NSI) spray was set to 1.8 kV, spray current at 2.1 μA, capillary voltage at −52.5V, tube lens voltage at −150V, simmer voltage at −42 V and capillary temperature was set to 300°C. The scanner acquired full MS sprectrum (80–1000 m/z range; ultra-high resolution, R=100000 at 1 Hz; maximum injection time 100 ms). Raw data were transformed using MSConvert19 and analyzed by MAVEN20.

Multiplexed mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics

Protein Digestion and TMT Labeling

Proteomes were subjected to multiplexed quantitative proteomics analysis using tandem-mass tag (TMT) reagents on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Disulfide bonds were reduced with ditheiothreitol (DTT) and free thiols alkylated with iodoacetamide (IAA) as described previously21. Reduced and alkylated proteins were then precipitated with tricholoracetic acid (TCA). Precipitated proteins were reconstituted in 300 μL of 1M urea in 50mM HEPES, pH 8.5 and digested first with endoproteinase Lys-C (Wako) for 17 hours at room temperature (RT) and then with sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega) for 6 hours at 37°C. The digest was acidified with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Peptides were desalted over Sep-Pak C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges (Waters). The concentration of the desalted peptide solutions was measured with a BCA assay (Thermo Scientific) and a maximum of 50 μg of peptides were aliquoted, then were dried under vacuum and stored at −80°C until they were labeled with TMT reagents. Peptides were labeled with 10-plex tandem mass tag (TMT) reagents (Thermo Scientific). TMT reagents were suspended in dry acetonitrile (ACN) at a concentration of 20 μg/μL. Dried peptides (50 μg) were re-suspended in 30% ACN in 200mM HEPES, pH 8.5 and 7.5 μL of the appropriate TMT reagent was added to the sample, which was incubated at RT for one hour. The reaction was then quenched by adding 6 μl of 5% (w/v) hydroxylamine in 200 mM HEPES (pH 8.5) and incubation for 15 min at RT. The solutions were acidified by adding 50 μl of 1% TFA.

Basic pH Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (bRPLC) Sample Fractionation

Sample fractionation was performed by basic pH reversed-phase liquid chromatography (bRPLC) with concatenated fraction combining22,23. Briefly, samples were re-suspended in 5% formic acid (FA)/5% ACN and separated over a 4.6 mm × 250 mm ZORBAX Extend C18 column (5 μm, 80 Å, Agilent Technologies) on an Agilent 1260 HPLC system outfitted with a fraction collector, degasser and variable wavelength detector. The separation was performed applying a gradient build from 22 to 35% ACN in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 60 min at a flow-rate of 0.5 mL/minute. A total of 96 fractions were collected, which were combined in a total of 12 fractions. The combined fractions were dried under vacuum, re-constituted with 8 μl of 5% FA/5% ACN, 3 μl of which were analyzed by LC-MS2/MS3 for identification and quantification.

Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

All LC-MS2/MS3 experiments were analyzed by microcapillary liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer and using a recently introduced multistage (MS3) method to provide highly accurate quantification21,24. The mass spectrometer was equipped with an EASY-nLC 1000 integrated autosampler and HPLC pump system. Peptides were separated over a 100 μm inner diameter microcapillary column in-house packed with first 0.5 cm of Magic C4 resin (5 μm, 100Å, Michrom Bioresources), then with 0.5 cm of Maccel C18 resin (3 μm, 200 Å, Nest Group) and 29 cm of GP-C18 resin (1.8 μm, 120 Å, Sepax Technologies). Peptides were eluted applying a gradient of 8–27% ACN in 0.125% formic acid over 165 min at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. To identify and quantify the TMT-labeled peptides we applied a synchronous precursor selection MS3 method21,24,25 in a data dependent mode. The scan sequence was started with the acquisition of a full MS or MS1 one spectrum acquired in the Orbitrap (m/z range, 500–1200; resolution, 60,000; AGC target, 5×105; maximum injection time, 100 ms), and the ten most intense peptide ions from detected in the full MS spectrum were then subjected to MS2 and MS3 analysis, while the acquisition time was optimized in an automated fashion (Top Speed, 5 sec). MS2 scans were done in the linear ion trap using the following settings: quadrupole isolation at an isolation width of 0.5Th; fragmentation method, CID; AGC target, 1×104; maximum injection time, 35 ms; normalized collision energy, 30%). Using synchronous precursor selection the 10 most abundant fragment ions were selected for the MS3 experiment following each MS2 scan. The fragment ions were further fragmented using the HCD fragmentation (normalized collision energy, 50%) and the MS3 spectrum was acquired in the Orbitrap (resolution, 60,000; AGC target, 5×104; maximum injection time, 250ms).

Data analysis was performed on an in-house generated SEQUEST-based26 software platform. RAW files were converted into the mzXML format using a modified version of ReAdW.exe. MS2 spectra were searched against a protein sequence database containing all protein sequences in the human UniProt database (downloaded 02/04/2014) as well as that of known contaminants such as porcine trypsin. This target component of the database was followed by a decoy component containing the same protein sequences but in flipped (or reversed) order 27. MS2 spectra were matched against peptide sequences with both termini consistent with trypsin specificity and allowing two missed trypsin cleavages. The precursor ion m/z tolerance was set to 50 ppm, TMT tags on the N-terminus and on lysine residues (229.162932Da) as well as carbamidomethylation (57.021464Da) on cysteine residues were set as static modification, and oxidation (15.994915Da) of methionines as variable modification. Using the target-decoy database search strategy27 a spectra assignment false discovery rate of less than 1% was achieved through using linear discriminant analysis with a single discriminant score calculated from the following SEQUEST search score and peptide sequence properties: mass deviation, XCorr, dCn, number of missed trypsin cleavages, and peptide length28. The probability of a peptide assignment to be correct was calculated using a posterior error histogram and the probabilities for all peptides assigned to a protein were combined to filter the data set for a protein FDR of less than 1%. Peptides with sequences that were contained in more than one protein sequence from the UniProt database were assigned to the protein with most matching peptides28. TMT reporter ion intensities were extracted as that of the most intense ion within a 0.03Th window around the predicted reporter ion intensities in the collected MS3 spectra. Only MS3 with an average signal-to-noise value of larger than 28 per reporter ion as well as with an isolation specificity21 of larger than 0.75 were considered for quantification. Reporter ions from all peptides assigned to a protein were summed to define the protein intensity. A two-step normalization of the protein TMT-intensities was performed by first normalizing the protein intensities over all acquired TMT channels for each protein based to the median average protein intensity calculated for all proteins. To correct for slight mixing errors of the peptide mixture from each sample a median of the normalized intensities was calculated from all protein intensities in each TMT channel and the protein intensities were normalized to the median value of these median intensities.

Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WBGS), processing and analysis

WBGS libraries were constructed as follows: 200 ng of genomic DNA was fragmented using a Covaris S2 for 6 min according to the following program: duty cycle 5%; intensity 5; cycle per burst 200. The sheared DNA was purified using the DNA Clean & Concentrator kit from Zymo Research and bisulfite conversion of purified DNA was then conducted using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research) per the manufacturer’s instructions, eluting to 15 μl low TE buffer. To minimize degradation during storage, the converted DNA was immediately processed to generate the WGBS libraries using the Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq DNA library kit (Swift Biosciences) following the standard protocol. The libraries were sequenced for 100-bp paired-end reads on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer, as previously described29. WBGS raw sequencing reads were aligned to mm9 build of the mouse genome using BSMAP30. DNA methylation calling for individual CpG sites was performed using mcall from the MOABS package31. Calculation of the average methylation of individual features and identification of differentially methylated features was done as previously described32. Briefly, average methylation for a feature was calculated as the coverage-weighted average across replicates of methylation at each CpG within the feature. Differentially methylated tiles were identified using a coverage-weighted two-sample t-test with CpG methylation levels within the tile as samples. Only CpGs with 5x coverage and features with at least 2CpGs satisfying this coverage threshold were used in the analysis. Feature definitions were downloaded from ENSEMBL for promoters, exons and introns and from UCSC for isnlands, shores, LINEs, SINEs, LTRs, satellites and microsatellites. Intersection between bed files was calculated using intersectBed from the Bedtools package33. Hierarchical clustering was done using the hclust function in R, with Euclidean distance as the distance metric. For all analyses, methylation at sex chromosomes was discarded. Bisulfite conversion rates and sequencing statistics can be found in Supplementary Data Table 3. Raw sequencing files can be found under the Superseries record GSE86145 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE86145).

Generation of the list of SAM-dependent enzymes

The list of transferases (Class 2 enzymes) was downloaded from ExplorEnz (http://www.enzyme-database.org). This list was hand-curated for mammalian genes and the 183 genes collected are considered the complete class of SAM-utilizing enzymes.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. LKB1 suppresses KRASG12D driven tumourigenesis and limits glycolysis in primary pancreatic ductal epithelial cells.

a, Schematic of GEM models. Sox9-CreER, LKB1L/L, and LSL-KRASG12D/+ mice were crossed to generate four cohorts: WT (Sox9-CreER), L (Sox9-CreER;LKB1L/L), K (Sox9-CreER;LSL-KRASG12D/+) and KL (Sox9-CreER;LSL-KRASG12D/+;LKB1L/L). Genetic lesions were induced by intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen at 6 weeks of age, after which mice were observed for signs of disease and sacrificed when KL animals were moribund (20–25 weeks of age). The WT, K, and L mice had no signs of illness or other abnormalities at this time point. b, Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of representative pancreata from WT and L mice (n=4 mice per group). Scale bars, 50 μm. c, Schematic of primary pancreatic ductal epithelial cell system. d, volume and e, weight of subcutaneous tumours derived from ductal cells of the indicated genotypes (n=4 tumours per group). Error bars are s.e.m. For source data on tumour volume, see Supplementary Data Table 4. f, Weight of subcutaneous tumours from K (n=6), KL (n=8) and KL cells transduced with retrovirus expressing LKB1 cDNA (rescue, n=8). g, Number of colonies formed in soft agar by K (none detected) or KL cells (n=6 independent biological replicates). Error bars are s.e.m. h, Proliferation of K and KL cells in nutrient-replete media (n=4). i, Proliferation of KL cells transduced with retroviruses expressing empty vector or LKB1 (rescue) (n=3). j, Proliferation of wild type (WT), KRASG12D/+ (K), LKB1−/− (L) and KRASG12D/+;LKB1−/− (KL) cells (n=6). k–t, In vitro studies of K and KL cells. k, Detection of GLUT1 (SLC2A1) by immunofluorescence (scale bar, 20 μm) or immunoblot. 2-(4-amidinophenyl)-1H-indole-6-carboxamidine (DAPI) was used to visualize nuclei. Actin was used as the loading control. For gel source see Supplementary Data Figure 1. l, Steady state ATP levels under nutrient replete conditions measured by Cell Titer Glo (Promega), normalized to cell number and expressed as relative to ATP levels in K cells (n=4). m, Intracellular levels of pyruvate, lactate, and TCA cycle metabolites as detected by GC-MS. Values are normalized to cell number. Data are expressed as relative to the levels in K cells (n=6 biological replicates). n, Three-day proliferation of cells in 25 mM glucose or acutely switched to media with the indicated reduced glucose concentrations (n=6). Data are expressed as relative to day 0. o–q, Proliferation of cells treated with 5 mM 2-deoxyglucose (2DG) (o), 5 mM dichloroacetate (DCA) (b) or 20 μM galloflavin (gallo) (q). Values are expressed as percentage of normal growth (2DG=6, DCA, n=8, gallo, n=6). r–t, WT, K, L and KL cells were measured for (r) glucose uptake using 2NBDG (n=6), (s) lactate release into the media (n=4), and (t) expression of glycolytic genes (n=6). Shown are data pooled from two (j, l, n–r) or three (t) experiments or representative of 2 (h, i, s) experiments. For all panels, error bars are standard deviation unless otherwise stated and statistical significance is indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Extended Data Figure 2. LKB1 loss induces the serine-glycine-one-carbon network.

a, GSEA showing enrichment of proteins involved in the serine/glycine/one-carbon network18 in KL cells compared to K cells using global proteomics (n=4 samples/group). b, Plot of isotopomer abundance of 13C-U-Glucose derived intracellular M+3 lactate over time (n=3 independent biological replicates). c, Plot of isotopomer abundance of 13C-U-Glucose-derived intracellular M+2 glycine over time (n=3 independent biological replicates). d, Intracellular levels of serine, glycine and glutamine as detected by GC-MS. Values are normalized to cell number. Data are expressed as relative to the levels in K cells (n=6 biological replicates). e, PSAT1 and GLDC expression determined by immunoblot in K and KL cells as well as KL cells transduced with LKB1 cDNA. Actin was used as loading control. For gel source see Supplementary Data Figure 1. f, GSEA of RNA-seq data showing suppression of genes involved in glycolysis, serine biosynthesis, folate cycle and the serine/glycine/one-carbon network upon re-expression of LKB1 cDNA in KL cells (i.e. rescue, n=2 samples) compared to parental KL cells (n=4 samples). g, Plot of isotopomer abundance of 13C-U-Glucose derived intracellular M+3 serine 6hrs after addition of 13C-U-Glucose (n=3 independent biological replicates). For all panels, error bars are standard deviation unless otherwise stated and statistical significance is indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Extended Data Figure 3. The de novo serine biosynthesis pathway is required for KL but not KPC tumour growth.

a, Proliferation of KL cells transduced with vector or LKB1 cDNA and cultured in the presence or absence of 0.4 mM serine. Growth is expressed as relative to day 0 (n=3). Note that LKB1 re-expression slows growth and results in sensitivity to serine deprivation. b, qRT-PCR showing effective knockdown of PSAT1 in K, KL, KPC and KIC cells transduced with shControl or two different hairpins against PSAT1 (n=2). Data are expressed as relative to shControl for each cell line. 18S rRNA was used for normalization. c, Number of colonies formed in soft agar by KL cells transduced with shControl or two different hairpins against PSAT1 (n=6). d, Proliferation of K or KL cells transduced with shControl or two independent hairpins against PSAT1 in the absence of serine. Data are expressed as percentage of growth in the presence of 0.4 mM serine (n=6). e, qRT-PCR showing effective knockdown of endogenous mouse PSAT1 (mPSAT1, endogenous) and forced expression of human PSAT1 (hPSAT1, exogenous) in KL cells transduced with shControl, shPSAT1-1, shPSAT1-2 and vector or hPSAT1 cDNA. Data are normalized to 18s rRNA (n=2). f, Weight at the time of harvesting of subcutaneous tumours from KL cells transduced with shControl (n=8), shPSAT1-1 (n=12), or shSPAT1-2 (n=12). Error bars are s.e.m. g, H&E stained sections and immunofluorescence analysis of representative tumours derived from subcutaneous injections of KL cells transduced with shControl, shPSAT1-1, or shPSAT1-2. Note that PSAT1 knockdown tumours have a reduction in malignant glands (arrows) relative to the fibrotic stroma. Lower panels: Anti-CK19 (green) was used to visualize the neoplastic epithelium and anti-PCNA (red) was used to mark proliferation. DAPI was used to stain nuclei (blue). h, Proliferation of KPC and KIC pancreatic cancer cells transduced with shControl or two independent hairpins against PSAT1. Growth is expressed as relative to day 0 (n=6 for KPC and n=4 for KIC). i–k, KPC cells were transduced with shControl (n=6), shPSAT1-1 (n=6) or shSPAT1-2 (n=4) and injected into SCID mice. i, Volume (left panel) and weight (right panel) of subcutaneous tumours. Error bars are s.e.m. For source data on tumour volume, see Supplementary Data Table 4. j and k, Tumours in (i) were stained using anti-CK19 antibody (green) to visualize the neoplastic epithelium and anti-PCNA staining (red) to mark proliferating cells. DAPI was used to stain nuclei (blue). The proportion of stained CK19+ cells is quantified in (j) (n=4, representative tumours) and CK19+ cells with nuclear PCNA staining are quantified in (j). There are no significant effects on any of these parameters. k, H&E stained sections (top panels) and immunofluorescence analysis (bottom panels) of representative tumours. Scale bars, 100 μm. Insets are three-fold magnification. Data pooled from two (c, d) or representative of two (a, b, e) or three (h) experiments. For all panels, error bars are standard deviation unless otherwise stated and statistical significance is indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Extended Data Figure 4. Characterization of serine-glycine one-carbon pathway in KL cells.

a, Detailed graph of SGOC network. Enzymatic inhibitors used in this study are marked in red. b, Reactive oxygen species in K or KL cells transduced with shControl, shPSAT1-1 or shPSAT1-2 were measured by DCFDA (left) and CellRox staining (right). Data are normalized to cell number (n=4). c, Six-day proliferation assay of KL cells transduced with shControl, shPSAT1-1 or shPSAT1-2, showing lack of growth rescue by N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Data are expressed as relative to day 0 (n=6). d, Three-day growth assay of KL cells transduced with shControl, shPSAT1-1 or shPSAT1-2, showing the lack of rescue by excess nucleosides (adenosine, guanosine, thymidine, uridine, cytidine, 1 mM each). Data are presented as percentage of the growth of shControl cells (n=16). e, Proliferation of K or KL cells treated with aminooxyacetate (AOA). Data are expressed as relative to day 0 (n=8). f, Five-day proliferation of K or KL cells treated with AOA and/or NAC. Data are expressed as relative to day 0 (n=6). g, Data from RNA-seq (left panel) and quantitative proteomics (right panel) showing levels of genes involved in the production of SAM in K and KL. The data plotted are expressed as mean-centered values. h, Proliferation of K or KL cells treated with 2 mM cycloleucine. Data are expressed as percentage of the growth of vehicle treated cells (n=12). Shown are data pooled from two (b–f, h) experiments. For all panels, error bars are standard deviation unless otherwise stated and statistical significance is indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Extended Data Figure 5. Deletion of LKB1 induces DNMT1 and DNMT3A expression and increases global DNA methylation.

a, Heat map of RNA-seq data showing levels of the differentially regulated SAM-utilizing enzymes. Plotted data are expressed as mean centered values. b, Expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3A in K, KL, and KL cells transduced with LKB1 cDNA (rescue) was measured by qRT-PCR. Levels were normalized to 18S rRNA. Data are expressed as relative to K cells (n=4, representative of two experiments). c, Immunoblots of lysates from K, KL or ‘rescue’ cells were probed for DNMT1 or DNMT3A. Actin is used as loading control. For gel source see Supplementary Data Figure 1. d, Measurement of SAM in K and KL cells treated with 5-Aza-2-deoxycytidine (Decitabine) or RG108 for 3 days. In each case, data are expressed as relative to the amount of SAM in K-vehicle treated cells that is arbitrarily set to 1 (n=6 independent replicates). e, Immunofluorescence staining and quantitation of 5-methyl-cytosine (5mC) in K or KL cells (77–130 cells). Scale bar, 25 μm. f, Dot blot of DNA isolated from K or KL cells probed with anti-5-methyl-cytosine antibody (5mC). Quantitated signal was normalized to total DNA as measured by methylene blue staining (n=4, independent replicates). g, Dot blot of DNA isolated from KL cells transduced with empty vector or LKB1 cDNA probed with anti-5mC antibody. Quantitated signal was normalized to total DNA as measured by methylene blue staining (n=3, independent replicates). h, Immunoblot analysis of histone 3 (H3) methyl marks from K or KL cells. Data are normalized to total H3 (K4me3, n=2, K27me3, n=5, K36me3, n=5, independent replicates). For gel source see Supplementary Data Figure 1. i, Dot blot of DNA isolated from K or KL cells probed with anti-5-hydroxymethyl-cytosine antibody (5hmC). Quantitated signal is normalized to total DNA as measured by methylene blue staining (n=4, independent replicates). For all panels, error bars are standard deviation unless otherwise stated and statistical significance is indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Extended Data Figure 6. Serine pathway activity sustains DNA methylation in KL cells.

a, Dot blot of DNA isolated from K or KL cells transduced with shControl, shPSAT1-1 or shPSAT1-2 probed with anti-5mC antibody. Total DNA was visualized by methylene blue staining. Graph shows quantitated signal normalized to total DNA as measured by methylene blue staining (K cells, n=4, KL cells, n=8, independent replicates). b, Dot blot of DNA isolated from KPC cells transduced with shControl, shPSAT1-1 or shPSAT1-2 probed with anti-5mC antibody. The graph shows quantitated signal normalized to total DNA (n=4, independent replicates). c, Dot blot of DNA probed with anti-5mC antibody. DNA was isolated from KL cells first transduced with vector or human PSAT1 then transduced with shControl, shPSAT1-1/2. Graph shows quantitated signal normalized to total DNA as measured by methylene blue staining (n=3, independent replicates). d, Expression of serine pathway genes and DNMTs genes in WT, K, L or KL cells by qRT-PCR. Data are normalized to 18S and expressed as relative to K (n=6, pooled data from two experiments). e, Plots of isotopomer abundance of 13C-U-Glucose-derived M+3 serine and M+2 glycine 6 hrs after additoin of 13C-U-Glucose (n=6 independent biological replicates). f, Quantitated DNA dot blot signal of DNA isolated from WT, K, L or KL cells probed with anti-5-methyl-cytosine antibody (5mC) normalized to total DNA as measured by methylene blue staining (n=4, independent replicates). g, Five-day growth of WT, K, L or KL cells transduced with shControl or two hairpins against PSAT1. Data are expressed as relative to day 0 (n=4, pooled from two experiments). For all panels, error bars are standard deviation unless otherwise stated and statistical significance is indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Extended Data Figure 7. LKB1-mediated regulation of glycolysis/SGOC/DNMT pathway involves the AMKP/mTOR axis.