Abstract

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), chronic non-communicable diseases and cardiovascular diseases in particular, are progressively taking over infectious diseases as the leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Heart failure is a major public health problem in the region. We summarize here available data on the prevalence, aetiologies, treatment, rates and predictors of mortality due to heart failure in SSA.

Keywords: Heart failure, Prevalence, Aetiologies, Treatment, Mortality, Sub-Saharan Africa

Specifications Table

| Subject area | Medicine |

| More specific subject area | Cardiology |

| Type of data | Data presented in tables and figures |

| How data was acquired | Systematic search of literature |

| Data format | Raw and analyzed data |

| Experimental factors | Not applicable |

| Experimental features | Not applicable |

| Data source location | Not applicable |

| Data accessibility | All data are included in this article |

| Related research article | Heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa: a contemporaneous systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology; In Press |

Value of the data

-

–

This work provides a deeper understanding of the prevalence, etiologies and prognosis of heart failure in SSA.

-

–

The data allow examination of the different medications used for the treatment of heart failure and therefore could help in changing practices for an optimal management of this pathology.

-

–

The data could be used as a baseline for comparison in future studies.

1. Data

In SSA, heart failure is a major public health problem, associated with high morbidity and mortality. Due to the shortage of data to distinctly understand the epidemiology of this pathology in this part of the world, we present here a summary of available data on the prevalence, aetiology, treatment, and prognosis of heart failure in SSA.

2. Experimental design, materials, and methods

Through a systematic literature search in MEDLINE and EMBASE (search strategies are presented in Table 1, Table 2), we included all published studies from January 1, 1996 to June 23, 2017 with available data on the prevalence, incidence, aetiologies, diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of heart failure in patients aged 12 years and older, living in SSA. We excluded studies conducted exclusively on African populations living outside Africa, commentaries, editorials, letters to the editor, case reports and case-series of less than 30 participants, studies lacking relevant data to compute the prevalence of the different heart failure aetiologies or treatment, and for duplicate studies, the most comprehensive and/or recent study with the largest sample size was considered, studies with inaccessible full-text, even after request from the corresponding author.

Table 1.

Main search strategy for PubMed.

| Search | Search term | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heart failure [tiab] OR cardiac failure [tiab] OR cardiac insufficiency [tiab] OR heart disease [tiab] | 276, 088 |

| 2 | (((Africa* [tiab] OR Benin [tiab] OR Botswana [tiab] OR "Burkina Faso" [tiab] OR Burundi [tiab] OR Cameroon [tiab] OR "Canary Islands" [tiab] OR "Cape Verde" [tiab] OR "Central African Republic" [tiab] OR Chad [tiab] OR Comoros [tiab] OR Congo [tiab] OR "Democratic Republic of Congo" [tiab] OR Djibouti [tiab] OR "Equatorial Guinea" [tiab] OR Eritrea [tiab] OR Ethiopia [tiab] OR Gabon [tiab] OR Gambia [tiab] OR Ghana [tiab] OR Guinea [tiab] OR "Guinea Bissau" [tiab] OR "Ivory Coast" [tiab] OR "Cote d'Ivoire" [tiab] OR Jamahiriya [tiab] OR Kenya [tiab] OR Lesotho [tiab] OR Liberia [tiab] OR Madagascar [tiab] OR Malawi [tiab] OR Mali [tiab] OR Mauritania [tiab] OR Mauritius [tiab] OR Mayotte [tiab] OR Mozambique [tiab] OR Namibia [tiab] OR Niger [tiab] OR Nigeria [tiab] OR Principe [tiab] OR Reunion [tiab] OR Rwanda [tiab] OR "Sao Tome" [tiab] OR Senegal [tiab] OR Seychelles [tiab] OR "Sierra Leone" [tiab] OR Somalia [tiab] OR "South Africa" [tiab OR "St Helena" [tiab] OR Swaziland [tiab] OR Tanzania [tiab] OR Togo [tiab] OR Uganda [tiab] OR Zaire [tiab] OR Zambia [tiab] OR Zimbabwe [tiab] OR "Central Africa" [tiab] OR "Central African" [tiab] OR "West Africa" [tiab] OR "West African" [tiab] OR "Western Africa" [tiab] OR "Western African" [tiab] OR "East Africa" [tiab] OR "East African" [tiab] OR "Eastern Africa" [tiab] OR "Eastern African" [tiab] OR "South African" [tiab] OR "Southern Africa" [tiab] OR "Southern African" [tiab] OR "sub Saharan Africa" [tiab] OR "sub Saharan African" [tiab] OR "subSaharan Africa" [tiab] OR "subSaharan African" [tiab]) NOT ("guinea pig" [tiab] OR "guinea pigs" [tiab] OR "aspergillus niger [tiab]"))) AND (Heart failure [tiab] OR cardiac failure [tiab] OR cardiac insufficiency [tiab] OR heart disease [tiab]) | |

| 3 | #1 AND #2 | 5012 |

| 4 | #3 AND Search limits: From 1 January 1996 to 10 Oct 2017 | 2125 |

Table 2.

Main search strategy for EMBASE.

| #1 | ‘Heart failure’ OR ‘cardiac failure’ OR ‘cardiac insufficiency’ OR ‘heart disease’ | 658,990 |

| #2 | 'africa':ab,ti OR 'algeria':ab,ti OR 'angola':ab,ti OR 'benin':ab,ti OR 'botswana':ab,ti OR 'burkina faso':ab,ti OR 'burundi':ab,ti OR 'cameroon':ab,ti OR 'canary islands':ab,ti OR 'cape verde':ab,ti OR 'central african republic':ab,ti OR 'chad':ab,ti OR 'comoros':ab,ti OR 'congo':ab,ti OR 'democratic republic of congo':ab,ti OR 'djibouti':ab,ti OR 'egypt':ab,ti OR 'equatorial guinea':ab,ti OR 'eritrea':ab,ti OR 'ethiopia':ab,ti OR 'gabon':ab,ti OR 'gambia':ab,ti OR 'ghana':ab,ti OR 'guinea':ab,ti OR 'guinea bissau':ab,ti OR 'ivory coast':ab,ti OR 'cote d ivoire':ab,ti OR 'jamahiriya':ab,ti OR 'kenya':ab,ti OR 'lesotho':ab,ti OR 'liberia':ab,ti OR 'libya':ab,ti OR 'madagascar':ab,ti OR 'malawi':ab,ti OR 'mali':ab,ti OR 'mauritania':ab,ti OR 'mauritius':ab,ti OR 'mayotte':ab,ti OR 'morocco':ab,ti OR 'mozambique':ab,ti OR 'namibia':ab,ti OR 'niger':ab,ti OR 'nigeria':ab,ti OR 'principe':ab,ti OR 'reunion':ab,ti OR 'rwanda':ab,ti OR 'sao tome':ab,ti OR 'senegal':ab,ti OR 'seychelles':ab,ti OR 'sierra leone':ab,ti OR 'somalia':ab,ti OR 'south africa':ab,ti OR 'st helena':ab,ti OR 'sudan':ab,ti OR 'swaziland':ab,ti OR 'tanzania':ab,ti OR 'togo':ab,ti OR 'tunisia':ab,ti OR 'uganda':ab,ti OR 'western sahara':ab,ti OR 'zaire':ab,ti OR 'zambia':ab,ti OR 'zimbabwe':ab,ti OR 'central africa':ab,ti OR 'central african':ab,ti OR 'west africa':ab,ti OR 'west african':ab,ti OR 'western africa':ab,ti OR 'western african':ab,ti OR 'east africa':ab,ti OR 'east african':ab,ti OR 'eastern africa':ab,ti OR 'eastern african':ab,ti OR 'north africa':ab,ti OR 'north african':ab,ti OR 'northern africa':ab,ti OR 'northern african':ab,ti OR 'south african':ab,ti OR 'southern africa':ab,ti OR 'southern african':ab,ti OR 'sub saharan africa':ab,ti OR 'sub saharan african':ab,ti OR 'subsaharan africa':ab,ti OR 'subsaharan african':ab,ti | 408,647 |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 4165 |

| #4 | #3 AND Search limits: From 1 January 1996 to 10 Oct 2017 | 1660 |

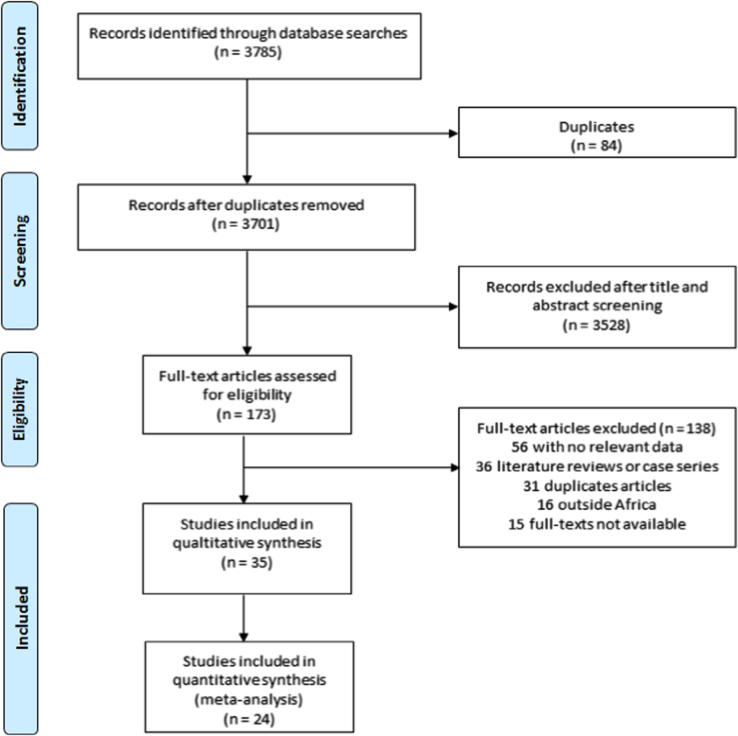

The titles and abstracts of articles retrieved from the bibliographic searches were independently screened by two investigators and full-texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed for final inclusion. All discrepancies the selection of studies were resolved through discussion or with the arbitrage of a third investigator. A total of 35 studies were included in this review [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. A summary of the selection process is presented in the Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study selection.

Data were then extracted using a predesigned data extraction form. The extracted data include: the last name of first author and the year of study publication, the country in which the study was conducted, Region (Western, Southern, Central, Eastern), area (urban, semi-urban or rural), study design (cross-sectional, cohort, case control), data collection (prospective versus retrospective), random sampling (yes versus no), study population, male proportion, mean or median age (in years), age range (in years), sample size, criteria used for the diagnosis of heart failure, number of cases of the different aetiologies of heart failure and number of cases of the different medications used for the treatment of heart failure.

The quality and risk of bias of all included studies are presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7. It was assessed using the risk of bias assessment tool for developed by Hoy et al. [36]. This tool was adapted for the different topics on heart failure covered in this review (prevalence, aetiology, treatment and prognosis of heart failure).

Table 3.

Summary table of included studies reporting on heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa (1996–2017).

| First name of author, publication year | Country | Region | Area | Study design | Study setting | Data collection | Study population | Random sampling | Male (%) | Mean age (in years) | Age range (in years) | Sample size | Criteria for diagnosis of HF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oyoo, 1999 [1] | Kenya | Eastern | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients ≥13 years admitted for congestive heart failure | No | 48.4 | NR | ≥13 | 91 | NR |

| Thiam, 2003 [2] | Senegal | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital- based | Prospective | Patients suffering from heart failure | No | NR | 50.0 | 12–91 | 170 | NR |

| Kingue, 2005 [3] | Cameroon | Central | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective and prospective | Patients presenting with clinical and echocardiographic signs of heart failure | No | 59.3 | 57.3 | ≥16 | 167 | NR |

| Familoni, 2007 [4] | Nigeria | Western | Semi-urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients presenting with acute heart failure | No | 61.7 | 57.6 | NR | 82 | NR |

| Owusu, 2007 [5] | Ghana | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients above 12 years admitted with diagnosis of heart failure | No | 51.5 | 51.1 | 13–90 | 167 | Framingham's criteria |

| Stewart, 2008 [6] | South Africa | Southern | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Novo presentations in patients with heart failure and related cardiomyopathies | No | 43 | 55.0 | NR | 884 | European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on HF |

| Ogah, 2008 [7] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | All cases of echocardiography done in the department of medicine between September 2005 and February 2007 | No | 51.6 | 54.0 | 15–90 | 1441 | NR |

| Onwuchekwa, 2009 [8] | Nigeria | Western | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Congestive cardiac failure cases admitted and/or discharged from the medical wards | No | 57.2 | 54.4 | 18–100 | 423 | Framingham's criteria |

| Maro, 2009 [9] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients admitted for congestive heart failure | No | 55.0 | NR | NR | 390 | Framingham's criteria |

| Damasceno, 2012 [10] | The THESUS-HF registry | SSA | – | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients admitted with acute heart failure | No | 49.2 | 52.3 | ˃12 | 1006 | European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on HF |

| Chansa, 2012 [11] | Zambia | Southern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Adult patients (>18 years) admitted for acute heart failure | No | 41 | 50 | >18 | 390 | European Society of Cardiology guidelines on HF |

| Kwan, 2013 [12] | Rwanda | Eastern | Rural | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Heart failure patients treated between November 2006 and march 2011 | No | 30.0 | NR | NR | 138 | NR |

| Massouré, 2013 [13] | Djibouti | Eastern | NR | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Djiboutian adults hospitalized for heart failure | No | 84.0 | 55.8 | 27–75 | 45 | Framingham's criteria |

| Ojji, 2013 [14] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Subjects of African descent with novo presentations of heart disease | No | 49.3 | 49.0 | NR | 1515 | European Society of Cardiology guidelines on HF |

| Sliwa, 2013 [15] | The THESUS-HF registry | SSA | – | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients presenting with acute heart failure | No | 49.1 | 52.3 | >12 | 1006 | European Society of Cardiology guidelines on HF |

| Makubi, 2014 [16] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients ≥ 18 years of age with heart failure defined by the Framingham criteria | No | 49.0 | 55.0 | ≥18 | 427 | Framingham's criteria |

| Ogah, 2014 [17] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients presenting with acute heart failure | No | 54.9 | 56.4 | NR | 452 | Framingham's criteria and ESC |

| Pio, 2014 [18] | Togo | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Hospitalized patients with heart failure | No | 48.2 | 52.2 | 18–106 | 297 | European Society of Cardiology guidelines on HF |

| Pio, 2014 [19] | Togo | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Files of patients hospitalized with heart failure | No | NR | 36.5 | 18–45 | 376 | NR |

| Osuji, 2014 [20] | Nigeria | Western | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | All medical admission | No | 50.5 | 60.7 | 18–110 | 537 | NR |

| Okello, 2014 [21] | Uganda | Eastern | NR | Cohort | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Patients admitted for acute heart failure | No | 30.3 | 52 | NR | 274 | NR |

| Dokainish, 2015 [22] | The INTER-CHF registry | SSA | – | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective, international, multicenter | Ambulatory and hospitalized adult patients with heart failure | Yes | 51.8 | 53.4 | ≥18 | 1294 | Boston criteria of HF |

| Adeoti, 2015 [23] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | All medical admissions | No | 55.0 | 50.9 | 16–102 | 3750 | NR |

| Ansa, 2016 [24] | Nigeria | Western | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective medical record review | All cardiovascular admissions to the medical wards | No | NR | NR | ≥18 | 144 | NR |

| Abebe 2016 [25] | Ethiopia | Eastern | Urban | Chart review | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Medical records of patients admitted for heart failure | NR | 30.2 | 53.6 | NR | 311 | NR |

| Ali, 2016 [26] | Ethiopia | Eastern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Adult patients (>18 years) admitted for heart failure | No | 50.7 | 50.9 | NR | 152 | Framingham's criteria |

| Kingery, 2017 [27] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Medical inpatients admitted for heart failure | No | 44.1 | 52.0 | ≥18 | 145 | Framingham's criteria |

| Boombhi, 2017 [28] | Cameroon | Central | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Patients hospitalized for acute heart failure, diagnosed on clinical and/or ultrasound evidence | No | 42.7 | 61,5 | 16–95 | 148 | NR |

| Traore, 2017 [29] | Ivory Coast | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Patients hospitalized for heart failure | No | 51.0 | NR | NR | 257 | NR |

| Bonsu, 2017 [30] | Ghana | Western | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Individuals aged ≥ 18 years discharged from first heart failure admission | No | 45.6 | 60.3 | ≥18 | 1488 | Framingham's criteria |

| Mwita, 2017 [31] | Botswana | Southern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients admitted with acute heart failure | No | 53.9 | 54.2 | 20–89 | 193 | NR |

| Pallangyo 2017 [32] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Adult patients (>18 years) admitted for heart failure | No | 43.5 | 46.4 | >18 | 463 | Framingham's criteria |

| Sani, 2017 [33] | The THESUS-HF registry | SSA | – | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients presenting with acute heart failure | No | 49.2 | 52.3 | >12 | 954 | European Society of Cardiology guidelines on HF |

| Ogah, 2014 [34] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients followed up for heart failure | No | 53.1 | 58.0 | NR | 239 | NR |

| Carlson, 2017 [35] | Kenya; Uganda | Eastern | NR | Cross sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Health facilities with available diagnostic technologies for HF diagnosis | No | NA | NA | NA | 340 health facilities (197 in Uganda and 143 in Kenya) | NA |

HF=Heart failure; THESUS-HF=sub-Saharan Africa Survey for Heart Failure; INTER-CHF=INTERnational Congestive Heart Failure; NR=Not reported; NA=Not applicable; SSA=Sub-Saharan Africa.

Table 4.

Summary tables for studies reporting on the prevalence of heart failure sub-Saharan Africa.

| First name of author, publication year | Country | Region | Area | Study design | Study setting | Data collection | Random sampling | Population | Male (%) | Mean age | Age range (in years) | Sample size | HF diagnostic tool | Prevalence of HF (%) | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osuji, 2014 [20] | Nigeria | Western | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | Patients admitted to the medical ward | 50.5 | 60.7 | 18–110 | 537 | NR | 30.9 | Moderate |

| Kingue, 2005 [3] | Cameroon | Central | Urban | Chart review | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | Patient >16 years admitted for cardiac pathologies | 59.3 | 57.3 | NR | 144 | Echocardiography | 30 | Moderate |

| Ansa, 2016 [24] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | All cases of medical admissions | 38.9 | 55 | 47–65 | 339 | NR | 42.5 | Low |

| Pio, 2014 [18] | Togo | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | Patients admitted to the cardiology unit | NR | 52.2 | 18–106 | 297 | Echocardiagraphy | 25.6 | High |

| Pio, 2014 [19] | Togo | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | Patients admitted to the cardiology unit | NR | 36.5 | 18–45 | 376 | Echocardiagraphy | 28.6 | Low |

| Ogah, 2014 [17] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | All medical admission | 54.9 | 56.4 | NR | 452 | Echocardiagraphy | 9.4 | High |

| Adeoti, 2015 [23] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | All medical admissions | 55.0 | 50.9 | 16–102 | 3750 | NR | 11.0 | Moderate |

NR=Not reported.

Table 5.

Aetiologies of heart failure across sub-Saharan Africa (1996–2017).

| First name of author, publication year | Country | Region | Area | Study design | Study setting | Data collection | Study population | Random sampling | Male (%) | Mean age (in years) | Age range (in years) | Sample size | Criteria for diagnosis of HF | Aetiology of heart failure | Diagnostic criteria of IHD | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oyoo, 1999 [1] | Kenya | Eastern | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients ≥13 years admitted for congestive heart failure | No | 48.4 | NR | ≥13 | 91 | NR | Rheumatic heart disease (32%); Cardiomyopathy (25.2%); Hypertensive heart disease (17.6%), pericardial disease (13.2%); Cor pulmonale (7.7%); Ischaemic heart disease (2.2%); Congenital heart disease (2.2%). | ECG and 2D Doppler Echocardiography | Moderate |

| Thiam, 2003 [2] | Senegal | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital- based | Prospective | Patients suffering from heart failure | No | NR | 50.0 | 12–91 | 170 | NR | Hypertension heart disease (34%); Valvular heart diseases (45%); Chronic renal failure (14.5%); Ischaemic heart disease (18.9%); Pulmonary embolism with Right heart failure (3.5%) and aetiology unspecified (6%) | Clinical presentation ECG and Echocardiography | High |

| Kingue, 2005 [3] | Cameroon | Central | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective and prospective | Patients presenting with clinical and echocardiographic signs of heart failure | No | 59.3 | 57.3 | ≥16 | 167 | NR | Hypertensive heart disease (54.5%); Cardiomyopathies (26.3%); Rheumatic heart disease (24.6%), Valvular heart diseases (24.6%), Ischaemic heart disease (2.4%). | 12-lead ECG and Echocardiography | Moderate |

| Familoni, 2007 [4] | Nigeria | Western | Semi-urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients presenting with acute heart failure | No | 61.7 | 57.6 | NR | 82 | NR | Hypertensive heart disease (43.4%); Dilated cardiomyopathy (28%); Rheumatic heart disease (9.8%), Endomyocardial fibrosis (2.2%); Cor pulmonale (3.7%); Ischaemic heart disease (8.5%); others (3.5%) | NR | Moderate |

| Owusu, 2007 [5] | Ghana | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients above 12 years admitted with diagnosis of heart failure | No | 51.5 | 51.1 | 13–90 | 167 | Framingham criteria | Hypertensive heart disease (42.5%); Rheumatic heart disease (21.6%); Dilated cardiomyopathy (17.4%); pericardial disease (4.2%); Ischaemic heart disease (3.6%); Cor pulmonale (2.4%) and Congenital heart disease (2.4%) | 12-lead ECG and Echocardiography | High |

| Stewart, 2008 [6] | South Africa | Southern | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Novo presentations in patients with heart failure and related cardiomyopathies | No | 43 | 55.0 | NR | 884 | ESC | Dilated cardiomyopathy (35%); Hypertensive heart disease (33%); Right heart failure (27%); Ischaemic heart disease (9%) and Valvular heart disease (8%) | 12-lead ECG; echocardiography; stress test; cardiac nuclear imaging and cardiac catheterization | High |

| Ogah, 2008 [7] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | All cases of echocardiography done in the department of medicine between September 2005 and February 2007 | No | 51.6 | 54.0 | 15–90 | 1441 | NR | Hypertensive heart disease (56.7%); Rheumatic heart disease (3.7%); Dilated cardiomyopathy (3.0%); Pericardial disease (1.8%); cor pulmonale (1.6%); Ischaemic heart disease (0.6%); Congenital heart disease (0.4%); diabetic heart disease (0.4%); thyroid heart disease (0.1%); Sickle cell cardiopathy (0.1%). | NR | High |

| Onwuchekwa, 2009 [8] | Nigeria | Western | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Congestive cardiac failure cases admitted and/or discharged from the medical wards | No | 57.2 | 54.4 | 18–100 | 423 | Framingham criteria | Hypertensive heart disease (56.3%); Cardiomyopathies (12.2%); Chronic renal failure (7.80%); Severe anemia (4.72%); Rheumatic heart diseases (4.26%). Cor pulmonale (2.13%); Congenital valvular heart disease (0.24%); Ischemic heart disease (0.24%); Missing (11.11%) | 12-lead ECG; echocardiography | Moderate |

| Damasceno, 2012 [10] | The THESUS-HF registry | SSA | – | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients admitted with acute heart failure | No | 49.2 | 52.3 | ˃12 | 1006 | European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on HF | Hypertensive heart disease (45.4); Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (18.8%); Rheumatic heart disease (14.3%); Ischaemic heart disease (7.7%); Peripartum cardiomyopathy (7.7%); Pericardial tamponade (6.8%); HIV cardiomyopathy (2.6%); Endomyocardial fibrosis (1.3%). | 12-lead ECG; echocardiography; stress test | Moderate |

| Kwan, 2013 [12] | Rwanda | Eastern | Rural | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Heart failure patients treated between November 2006 and march 2011 | No | 30.0 | NR | NR | 138 | NR | Dilated cardiomyopathy (54%), Rheumatic heart disease (25%), hypertensive heart disease (8%) and ischaemic heart disease (0%) | NR | Moderate |

| Massouré, 2013 [13] | Djibouti | Eastern | NR | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Adults hospitalized for heart failure | No | 84.0 | 55.8 | 27–75 | 45 | Framingham criteria | Coronary artery disease (62%); hypertensive heart disease (18%); rheumatic valvular disease (13%) and primary dilated cardiomyopathy (7%) | 12-lead ECG; echocardiography; stress test | Moderate |

| Ojji, 2013 [14] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients with novo presentations of heart disease | No | 49.3 | 49.0 | NR | 1515 | European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on HF | Hypertensive heart disease (60.6%); Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (12.0%); Valvular rheumatic heart disease (8.6%); peripartum cardiomyopathy (5.3%); Alcoholic cardiomyopathy (4.2%); Thyrotoxic heart disease (2.9%); right heart failure (2.5%); Ischaemic heart disease (0.4%) | ECG; Cardiac enzymes; Echocardiography | High |

| Makubi, 2014 [16] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients ≥18 years of age with heart failure defined by the Framingham criteria | No | 49.0 | 55.0 | ≥18 | 427 | Framingham criteria | Hypertensive heart disease (45%); Cardiomyopathy (28%); Rheumatic heart disease (12%); Ischaemic heart disease (9%); Othersa (6%) | 12-lead ECG; echocardiography; angiography | High |

| Ogah, 2014 [17] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Patients presenting with acute heart failure | No | 54.9 | 56.4 | NR | 452 | Framingham criteria and ESC | Hypertensive heart disease (78.5%); Dilated cardiomyopathy (7.5%); Cor pulmonale (4.4%); Pericardial disease (3.3%); Rheumatic heart disease (2.4%); Ischaemic heart disease (0.4%) | 12-lead ECG and Echocardiography | High |

| Pio, 2014 [18] | Togo | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | Hospitalized patients with heart failure | No | 48.2 | 52.2 | 18–106 | 297 | European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on HF | Hypertensive heart disease (43.1%); Ischaemic heart disease (19.2%); Peripartum cardiomyopathy (11.8%); valvulopathies (11.8%); HIV-related cardiopathy (3.4%); Thyrotoxic heart disease (3%); Cor pulmonale (2.7%); congenital cardiopathies (2.7%); Chronic alcoholism (2%) and idiopathic (5.9%). | ECG; Cardiac enzymes; Echocardiography | High |

| Pio, 2014 [19] | Togo | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Files of patients hospitalized with heart failure | No | NR | 36.5 | 18–45 | 376 | NR | Hypertensive heart disease (42.8%); Valvulopathies (18.1%); Peripartum cardiomyopathy (15.4%); Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (5.8%); Alcoholic cardiomyopathy (3.2%); IHD (2.7%); Congenital cardiopathy (2.7%); Cor pulmonale (2.1%); thyrotoxic heart failure (1.8%); Pericardial tamponade (1.1%) and HIV-associated myocarditis (1.1%) | ECG; Cardiac enzymes; Echocardiography | Low |

| Dokainish, 2015 [22] | The INTER-CHF registry | SSA | – | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective, international, multicenter | Ambulatory and hospitalized adult patients with heart failure | Yes | 51.8 | 53.4 | ≥18 | 1294 | Boston criteria of HF | Hypertensive heart disease (35%); Ischaemic cardiomyopathy (20%); Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (14.5%); Valvular rheumatic heart disease (7.2%); Endocrine/metabolic heart disease (5.3%); Vavlular non-rheumatic heart disease (2.3%); Alcohol/drug induced cardiopathy (0.7%); HIV cardiomyopathy (0.7%). | 12-lead ECG; echocardiography | Moderate |

| Ansa, 2016 [24] | Nigeria | Western | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective medical record review | All cardiovascular admissions to the medical wards | No | NR | NR | ≥18 | 144 | NR | Hypertensive heart disease (48.6%); dilated cardiomyopathy (35.4%); Anaemia (14.6%) and Rheumatic heart disease (1.4%) | NR | Low |

| Abebe 2016 [25] | Ethiopia | Eastern | Urban | Chart review | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Medical records of patients admitted for heart failure | NR | 30.2 | 53.6 | NR | 311 | NR | Valvular heart disease (40.8%); Hypertensive heart disease (16.1%); Ischaemic heart disease (15.8%); Dilated cardiomyopathy (12.5%), Cor pulmonale (4.5%); Others (10.3%) | NR | Moderate |

| Kingery, 2017 [27] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | Medical inpatients admitted for heart failure | No | 44.1 | 52.0 | ≥18 | 145 | Framingham criteria of HF | Hypertensive heart disease (42.8%); dilated cardiomyopathy (19.3%); Valvular heart disease (16.6%); cor pulmonale (7.6%); ischaemic heart disease (6.2%); Other causes (7.6%) | 12-lead ECG; echocardiography | High |

| Boombhi, 2017 [28] | Cameroon | Central | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Patients hospitalized for acute heart failure, diagnosed on clinical and/or ultrasound evidence | No | 42.7 | 61,5 | 16–95 | 148 | NR | Hypertensive heart disease (30.16%); Dilated cardiomyopathy (28.57%); Valvular heart disease (11.90%); Chronic cor pulmonale (8.73%); Ischemic heart disease (6.35%); Pericardial diseases (3.96%); Peripartum cardiomyopathy (3.18%) | 12-lead ECG; echocardiography | Low |

| Traore, 2017 [29] | Ivory Coast | Western | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | Patients hospitalized for heart failure | No | 51.0 | NR | NR | 257 | NR | Hypertensive heart disease (22.9%); Dilated cardiomyopathy (55.57%); Valvular heart disease (6.76%); Ischemic heart disease (11.23%); Other (9.9%) | Echocardiography ± coronarography | Low |

Othersa=Tuberculosis; HIV-related cardiomyopathy; endomyocardial fibrosis; obstructive pulmonary disease; IHD=Ischaemic heart disease; ECG=Electrocardiography; HF=Heart failure; THESUS-HF=sub-Saharan Africa Survey for Heart Failure; INTER-CHF=INTERnational Congestive Heart Failure; ESC=European Society of Cardiology; NR=not reported.

Table 6.

Summary of studies reporting on pharmacologic treatment of heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa.

| First name of author, publication year | Country | Region | Area | Study design | Study setting | Data collection | Random sampling | Male (%) | Mean age (in years) | Age range (in years) | Sample size | Criteria for diagnosis of HF | Treatment of heart failure | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingue, 2005 [10] | Cameroon | Central | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective and prospective | No | 59.3 | 57.3 | ≥16 | 167 | NR | Loop diuretics (90%); angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) (64.7%); beta-blockers (19.8%); digoxin (30.5%); aldosterone antagonists (25.5%) | Moderate |

| Stewart, 2008 [7] | South Africa | Southern | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | 43.0 | 55.0 | NR | 844 | ESC | Loop or thiazide diuretic (68%); ACEI (57.7%); beta-blocker (45.6%); digoxin (19%); aldosterone antagonist (42%); calcium channel blocker (18%) | High |

| Ogah, 2014 [26] | Nigeria | Western | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | 54.9 | 56.4 | NR | 452 | Framingham criteria and ESC | Loop diuretic (88.1%); ACEI (99.1%); beta-blockers (9.1%) digoxin (72.3%); long-acting calcium-channel blockers (26.8%); combined hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate (14.4%) | High |

| Damasceno, 2012 [17] | THESUS-HF Registry | SSA | NR | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | 49.2 | 52.3 | ˃12 | 1006 | ESC | Loop diuretic (79%); ACEI/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) (82%); beta-blockers (30%); Digoxin (60%); Aldosterone antagonist (75%); | Moderate |

| Makubi, 2014 [18] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | 49.0 | 55.0 | ≥18 | 427 | Framingham criteria | Loop diuretics (88%); ACEI/ARB (92%); β-Blockers (42%); Digoxin (39%); Aldosterone antagonist (72%); Calcium channel blockers (19%); Nitrates (64%); Hydralazine (4%) | High |

| Dokainish, 2016 [19] | INTER-CHF registry | SSA | Both | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective, international, multicenter | No | 51.8 | 53.4 | ≥18 | 1294 | Boston criteria of HF | Diuretic (93.7%); ACEI/ARB (77.1%); β-Blockers (48.3%); Digoxin (31.9%); Aldosterone Inhibitors (59.4%); | Moderate |

| Boombhi, 2017 [29] | Cameroon | Central | Urban | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | 42.7 | 61.5 | 16–96 | 148 | NR | Diuretics (93.2%); ACEI/ARB (50%); Beta-blockers (20.6%) | Low |

| Bonsu, 2017 [30] | Ghana | Western | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | 45.6 | 60.3 | ≥18 | 1488 | Framingham criteria of HF | Diuretics (68.4%); ACEI/ARB (62%); β-Blockers (32.5%); Digoxin (16.3%); Aldosterone antagonist (28%); Calcium channel blockers (44.9%); Nitrates (2.1%) | Low |

| Mwita, 2017 [31] | Botswana | Southern | Urban | Cohort | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | 53.9 | 54.2 | 20–89 | 193 | NR | ACEI/ARB (67.4%); β-Blockers (72.1%); Loop diuretics (86%); Digoxin (22.1%); Aldosterone antagonist (59.9%) | Moderate |

Table 7.

Summary of studies reporting on the mortality rate and/or predictors of mortality among heart failure patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

| First name of author, publication year | Country | Region | Area | Study setting | Data collection | Random sampling | Study Population | Male (%) | Mean age (in years) | Age range (in years) | Sample size | Duration of follow-up | Mortality rate | Predictor(s) of mortality (HR* or OR**) | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familoni, 2007 [4] | Nigeria | Western | Semi-Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Adult patients (>18 years) admitted for acute heart failure | 67.1 | 57.6 | NR | 82 | 3 years | 3-year mortality rate=67.1% | Age (HR=0.997); Systolic blood pressure (HR=1.002); Congestion score (HR=1.007) | Moderate |

| Maro, 2009 [9] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Patients admitted for congestive heart failure | 55.0 | NR | NR | 360 | 12 months | 360-day mortality rate=21.9% | NR | Moderate |

| Chansa, 2012 [11] | Zambia | Southern | Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Adult patients (>18 years) admitted for acute heart failure | 41 | 50 | NR | 390 | 30 days | In-hospital mortality rate=24.1% | Left ventricular ejection fraction <40% (HR=1.93); NYHA class IV (HR=1.92); Serum urea nitrogen >15 mmol/L (HR=2.10); Haemoglobin levels <12 g/dL (HR=1.34); Systolic blood pressure <115 mmHg (HR=1.92) | Moderate |

| 30-day mortality rate=35% | |||||||||||||||

| Sliwa, 2013 [15] | The THESUS-HF registry | SSA | – | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Patients presenting with acute heart failure | 49.1 | 52.3 | NR | 1006 | Six months | 60-day mortality rate=9.5% | Malignancy (HR=5.04); History of cor pulmonale (HR=2.50); Serum urea nitrogen (HR=1.39); Systolic blood pressure (HR=0.91); Rales (HR=2.18); West region (HR=1.83) | High |

| 180-day mortality rate=15.0% | |||||||||||||||

| Massouré, 2013 [13] | Djibouti | Eastern | Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Adult patients (> 18 years) admitted for heart failure | 84 | 55.8 | 27–75 | 45 | 14.4 months | Mortality rate=18.0% | NR | Moderate |

| Okello, 2014 [21] | Uganda | Eastern | NR | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | Patients admitted for acute heart failure | 30.3 | 52 | NR | 274 | 13 months | In-hospital mortality rate=18.3% | Hypotension on admission (adjusted OR=4.6); Reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (adjusted OR=7.6) | Low |

| Makubi, 2014 [16] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Adult patients (>18 years) with heart failure | 49.0 | 55 | >18 | 427 | 7 months | 22.4 per 100 person-years | Creatinine clearance (HR=0.98); Pulmonary hypertension (HR=2.11); Anaemia (HR=2.27); No formal education (HR=2.34); Inpatient (HR=3.23); Atrial fibrillation (HR=3.37). | High |

| Ali, 2016 [26] | Ethiopia | Eastern | Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Adult patients (> 18 years) admitted for heart failure | 50.7 | 50.9 | >18 | 152 | 9 months | In-hospital mortality rate=3.9% | NR | Low |

| Abebe, 2016 [25] | Ethiopia | Eastern | Urban | Hospital-based | Retrospective | NR | Adult patients admitted for HF | 30.2 | 53.8 | >18 | 311 | 25 months | Mortality rate=14.1% | Advanced age (HR=1.05), Hyponatremia (HR=0.91), elevated creatinine levels (HR=1.97), and absence of medication (spironolactone [HR=0.34], ACEI [HR=0.26] and statin [HR=0.19]) | Moderate |

| Kingery, 2017 [27] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Adult patients (>18 years) admitted for heart failure | 38.3 | 50.8 | >18 | 145 | 12 months | In-hospital mortality rate=25.2% | Low eGFR (HR=2.94); Proteinuria (HR=2.03). | High |

| 360-day mortality rate=57.9% | |||||||||||||||

| Bonsu, 2017 [30] | Ghana | Western | Urban | Hospital-based | Retrospective | No | Adult patients (> 18 years) admitted for heart failure | 45.6 | 60.3 | >18 | 1488 | 5 years | 5-year mortality rate=31.7% | Age (HR=1.01); NYHA IV (HR=1.96); Ejection fraction (HR=0.99); LDLC-C (HR=1.1); Chronic kidney disease (HR=1.74); Atrial fibrillation (HR=1.26); Anaemia (HR=1.40); Diabetes mellitus (HR=1.50); Statin (HR=0.70); Aldosterone antagonists (HR=0.81) | High |

| Mwita, 2017 [31] | Botswana | Southern | Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Adult patients (>18 years) admitted for acute heart failure | 53.9 | 54.2 | 20–89 | 193 | 1 year | In-hospital mortality rate=10.9% | Advanced age; Lower haemoglobin level; Lower eGFR; Lower serioum sodium levels; Higher length of hospital stay; Higher serum creatinine levels; Higher serum urea levels; Higher serum NT-proBNP levels | Moderate |

| 30-day mortality rate=14.7% | |||||||||||||||

| 180-day mortality rate=30.8% | |||||||||||||||

| Pallangyo 2017 [32] | Tanzania | Eastern | Urban | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Adult patients (>18 years) admitted for heart failure | 43.5 | 46.4 | >18 | 463 | 180 days | 180-day mortality rate=57.8% | Renal dysfunction (HR=1.9); Severe anaemia (HR=1.8); Hyponatraemia (HR=2.2); Rehospitalisation (HR=4.3); Cardiorenal anaemia syndrome (HR=2.1) | High |

| Sani, 2017 [33] | The THESUS-HF registry | SSA | – | Hospital-based | Prospective | No | Patients presenting with acute heart failure | 49.2 | 52.3 | >12 | 954 | 180 days | NR | Predictors of mortality within 60 days: Heart rate (HR=1.07); left atrial size (HR=1.00) | Low |

| Predictors of mortality within 180 days: Heart rate >80bpm (HR=1.25); left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole >9 mm (HR=1.32); Presence of aortic stenosis (HR=3.60) |

HR*=Hazard ratio; OR**=Odd's ratio; NYHA=New York Heart Association; bpm=Beats per minute; NR=Not reported; eGFR=Estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Data were analyzed using the ‘meta’ package of R software. A random-effects meta-analysis model was used to pool prevalence estimates after stabilization of the variance of the study-specific prevalence using the Freeman-Tukey single arc-sine transformation [37]. The Egger's test was used to assess publication bias which was considered significant if the p-value <0.1. Summary statistics from meta-analyses of prevalence studies on the medications used to treat heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Summary statistics from meta-analyses of prevalence studies on the medications used to treat heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Treatment | N studies | N participants | % (95% confidence interval) | I² (95% confidence interval) | H (95% confidence interval) | P heterogeneity | P Egger test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI/ARB | 9 | 5692 | 75.5 (64.4–85.1) | 98.8 (98.4–99.0) | 8.9 (7.8–10.2) | <0.0001 | 0.879 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 6 | 4925 | 51.5 (32.4–70.3) | 99.4 (99.3–99.6) | 13.4 (11.8–15.2) | <0.0001 | 0.807 |

| Digoxin | 7 | 5027 | 31.5 (19.4–45.0) | 98.9 (98.6–99.2) | 9.6 (8.3–11.2) | <0.0001 | 0.924 |

| Loop diuretics | 9 | 5692 | 81.6 (72.7–89.1) | 98.4 (97.8–98.8) | 7.8 (6.7–9.0) | <0.0001 | 0.806 |

| β-Blockers | 9 | 5692 | 31.4 (22.6–41.0) | 98.1 (97.4–98.6) | 7.3 (6.3–8.5) | <0.0001 | 0.549 |

ACEI=Angiotensin II enzyme inhibitor; ARB=Angiotensin receptor blocker; N=frequency; CI=confidence interval.

These data are attached to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in the International Journal of Cardiology [38].

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.dib.2018.01.100.

Contributor Information

Ulrich Flore Nyaga, Email: nyagaflore@gmail.com.

Jean Joel Bigna, Email: bignarimjj@yahoo.fr.

Valirie N. Agbor, Email: nvagbor@gmail.com.

Mickael Essouma, Email: essmic@rocketmail.com.

Ntobeko A.B. Ntusi, Email: ntobeko.ntusi@uct.ac.za.

Jean Jacques Noubiap, Email: noubiapjj@yahoo.fr.

Transparency document. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

References

- 1.Oyoo G.O., Ogola E.N. Clinical and socio demographic aspects of congestive heart failure patients at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr. Med. J. 1999;76:23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiam M. Cardiac insufficiency in the African cardiology milieu. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 2003;96:217–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingue S., Dzudie A., Menanga A., Akono M., Ouankou M., Muna W. A new look at adult chronic heart failure in Africa in the age of the Doppler echocardiography: experience of the medicine department at Yaounde General Hospital. Ann. Cardiol. Angeiol. (Paris) 2005;54:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ancard.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Familoni O., Olunuga T., Olufemi B. A clinical study of pattern and factors affecting outcome in Nigerian patients with advanced heart failure. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2007;18:308–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owusu I.K. Causes of heart failure as seen in Kumasi Ghana. Internet J. Third World Med. [Internet] 2006:5. 〈https://ispub.com/IJTWM/5/1/9012〉 (Available from) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart S., Wilkinson D., Hansen C., Vaghela V., Mvungi R., McMurray J. Predominance of heart failure in the Heart of Soweto Study cohort: emerging challenges for urban African communities. Circulation. 2008;118:2360–2367. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.786244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogah O.S., Adegbite G.D., Akinyemi R.O., Adesina J.O., Alabi A.A., Udofia O.I. Spectrum of heart diseases in a new cardiac service in Nigeria: an echocardiographic study of 1441 subjects in Abeokuta. BMC Res. Notes. 2008;1:98. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onwuchekwa A.C., Asekomeh G.E. Pattern of heart failure in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:745–750. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maro E.E., Kaushik R. The role of echocardiography in the management of patients with congestive heart failure. “Tanzanian experience”. Cent. Afr. J. Med. 2009;55:35–39. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v55i5-8.63638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damasceno A., Mayosi B.M., Sani M., Ogah O.S., Mondo C., Ojji D. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:1386–1394. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chansa P., Lakhi S., Ben A., Kalinichenko S., Sakr R. Factors associated with mortality in adults admitted with heart failure at the university teaching hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2012;30:32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwan G.F., Bukhman A.K., Miller A.C., Ngoga G., Mucumbitsi J., Bavuma C. A simplified echocardiographic strategy for heart failure diagnosis and management within an integrated noncommunicable disease clinic at district hospital level for sub-Saharan Africa. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massoure P.L., Roche N.C., Lamblin G., Topin F., Dehan C., Kaiser E. Heart failure patterns in Djibouti: epidemiologic transition. Med. Sante Trop. 2013;23:211–216. doi: 10.1684/mst.2013.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ojji D., Stewart S., Ajayi S., Manmak M., Sliwa K. A predominance of hypertensive heart failure in the Abuja Heart Study cohort of urban Nigerians: a prospective clinical registry of 1515 de novo cases. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013;15:835–842. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sliwa K., Davison B.A., Mayosi B.M., Damasceno A., Sani M., Ogah O.S. Readmission and death after an acute heart failure event: predictors and outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: results from the THESUS-HF registry. Eur. Heart J. 2013;34:3151–3159. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makubi A., Hage C., Lwakatare J., Kisenge P., Makani J., Rydén L. Contemporary aetiology, clinical characteristics and prognosis of adults with heart failure observed in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania: the prospective Tanzania Heart Failure (TaHeF) study. Heart. 2014;100:1235–1241. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogah O.S., Stewart S., Falase A.O., Akinyemi J.O., Adegbite G.D., Alabi A.A. Contemporary profile of acute heart failure in Southern Nigeria: data from the Abeokuta Heart Failure Clinical Registry. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pio M., Afassinou Y., Pessinaba S., Baragou S., N’djao J., Atta B. Epidémiologie et étiologies des insuffisances cardiaques à Lomé. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014:18. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.183.3983. 〈http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4236922/〉 (Available from) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pio M., Goeh-Akue E., Afassinou Y., Baragou S., Atta B., Missihoun E. Insuffisances cardiaques du sujet jeune: aspects épidémiologiques, cliniques et étiologiques au CHU Sylvanus Olympio de Lomé. Ann. De. Cardiol. d’Angéiologie. 2014;63:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ancard.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osuji C.U., Onwubuya E.I., Ahaneku G.I., Omejua E.G. Pattern of cardiovascular admissions at Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital Nnewi, South East Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014:17. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.17.116.1837. 〈http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4119432/〉 (Available from) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okello S., Rogers O., Byamugisha A., Rwebembera J., Buda A.J. Characteristics of acute heart failure hospitalizations in a general medical ward in Southwestern Uganda. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;176:1233–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dokainish H., Teo K., Zhu J., Roy A., AlHabib K.F., ElSayed A. Heart Failure in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and South America: the INTER-CHF study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;204:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.11.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adeoti A.O., Ajayi E.A., Ajayi A.O., Dada S.A., Fadare J.O., Akolawole M. Pattern and outcome of medical admissions in Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti- a 5 year review. Am. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2015;5:92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ansa V., Otu A., Oku A., Njideoffor U., Nworah C., Odigwe C. Patient outcomes following after-hours and weekend admissions for cardiovascular disease in a tertiary hospital in Calabar, Nigeria. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2016;27:328–332. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abebe T.B., Gebreyohannes E.A., Tefera Y.G., Abegaz T.M. Patients with HFpEF and HFrEF have different clinical characteristics but similar prognosis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016;16:232. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0418-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali K., Workicho A., Gudina E.K. Hyponatremia in patients hospitalized with heart failure: a condition often overlooked in low-income settings. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2016;9:267–273. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S110872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kingery J.R., Yango M., Wajanga B., Kalokola F., Brejt J., Kataraihya J. Heart failure, post-hospital mortality and renal function in Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017:0. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.025. 〈http://www.internationaljournalofcardiology.com/article/S0167-5273(16)33889-X/fulltext〉 (Available from) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boombhi M., Moampea M., Kuate L., Menanga A., Hamadou, Kingue S. Clinical pattern and outcome of acute heart failure at the Yaounde Central Hospital. Open Access Libr. J. 2017;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traore F., Bamba K., Koffi F., Ngoran Y., Mottoh M., Esale S. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a report about 64 cases followed at the Heart Institute of Abidjan. World J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonsu K.O., Owusu I.K., Buabeng K.O., Reidpath D.D., Kadirvelu A. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients admitted for heart failure: a 5-year retrospective study of African patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017;238:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mwita J.C., Dewhurst M.J., Magafu M.G., Goepamang M., Omech B., Majuta K.L. Presentation and mortality of patients hospitalised with acute heart failure in Botswana. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2017;28:112–117. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pallangyo P., Fredrick F., Bhalia S., Nicholaus P., Kisenge P., Mtinangi B. Cardiorenal anemia syndrome and survival among heart failure patients in tanzania: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017;17:59. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0497-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sani M.U., Davison B.A., Cotter G., Damasceno A., Mayosi B.M., Ogah O.S. Echocardiographic predictors of outcome in acute heart failure patients in sub-Saharan Africa: insights from THESUS-HF. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2017;28:60–67. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogah O.S., Stewart S., Onwujekwe O.E., Falase A.O., Adebayo S.O., Olunuga T. Economic burden of heart failure: investigating outpatient and inpatient costs in Abeokuta, Southwest Nigeria. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlson S., Duber H.C., Achan J., Ikilezi G., Mokdad A.A., Stergachis A. Capacity for diagnosis and treatment of heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa. Heart. 2016;0:1–6. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoy D., Brooks P., Woolf A., Blyth F., March L., Bain C. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012;65:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller J.J. The inverse of the freeman – tukey double arcsine transformation. Am. Stat. 1978;32:138. (138) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agbor V.N., Essouma M., Ntusi N.A., Nyaga U.F., Bigna J.J., Noubiap J.J. Heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa: a contemporaneous systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.048. submitted to Journal. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.