Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Transfer of patient care from an intensive care unit (ICU) to a hospital ward is often challenging, high risk and inefficient. We assessed patient and provider perspectives on barriers and facilitators to high-quality transfers and recommendations to improve the transfer process.

METHODS:

We conducted semistructured interviews of participants from a multicentre prospective cohort study of ICU transfers conducted at 10 hospitals across Canada. We purposively sampled 1 patient, 1 family member of a patient, 1 ICU provider, and 1 ward provider at each of the 8 English-speaking sites. Qualitative content analysis was used to derive themes, subthemes and recommendations.

RESULTS:

The 35 participants described 3 interrelated, overarching themes perceived as barriers or facilitators to high-quality patient transfers: resource availability, communication and institutional culture. Common recommendations suggested to improve ICU transfers included implementing standardized communication tools that streamline provider–provider and provider–patient communication, using multimodal communication to facilitate timely, accurate, durable and mutually reinforcing information transfer; and developing procedures to manage delays in transfer to ensure continuity of care for patients in the ICU waiting for a hospital ward bed.

INTERPRETATION:

Patient and provider perspectives attribute breakdown of ICU-to-ward transfers of care to resource availability, communication and institutional culture. Patients and providers recommend standardized, multimodal communication and transfer procedures to improve quality of care.

The transfer of patients from the intensive care unit (ICU) to a hospital ward is one of the most challenging, high-risk and inefficient transitions of care because the patients are among the sickest in the health care system, they are transitioning from high technological units to less acute environments, and many interprofessional providers are involved in exchanges of information and responsibility. Challenges associated with transfers from ICU, including increased risk of medical errors,1 adverse events,2,3 readmission,4 dissatisfaction with care5 and death,6 have been previously described using primarily quantitative approaches.7 Understanding patient and provider perspectives is vital to guiding efforts to improve transfers from ICU to hospital ward. Previous studies have reported the experiences of individual provider groups (physicians or nurses)8,9 or patients10,11 at single health science centres.12,13 These assessments can inform local initiatives to improve quality targeted to individual stakeholder groups, but have limited transferability and cannot capture the complexity of interprofessional, multidisciplinary and patient-centred transfers of care.

A comprehensive joint assessment of key stakeholders’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to high-quality transfers across multiple hospitals is needed to inform efforts at quality improvement more broadly. To address this knowledge gap, and to generate recommendations for how transfers of care from the ICU might be improved, we sought the perspectives of a diverse group of patients, their family members, and ICU and hospital ward physicians and nurses (providers) from multiple institutions.

Methods

Study design

This study was part of a multicentre prospective cohort study14 that used standardized surveys and case report forms to provide a 360-degree description of transfers from ICU to hospital ward in 10 hospitals in 7 cities across Canada. The study was conducted from July 2014 to January 2016. For each patient transfer in the study sample, we invited the patient, a family member and 4 providers directly involved in the transfer of care (1 ICU physician, 1 ICU nurse, 1 ward physician, 1 ward nurse) to participate in a survey to describe their experiences with the ICU to hospital ward transfer. Findings from the survey showed that failures of patient flow and communication are common, identifying a need for further qualitative inquiry into barriers and facilitators of high-quality patient transfers.14

Participants

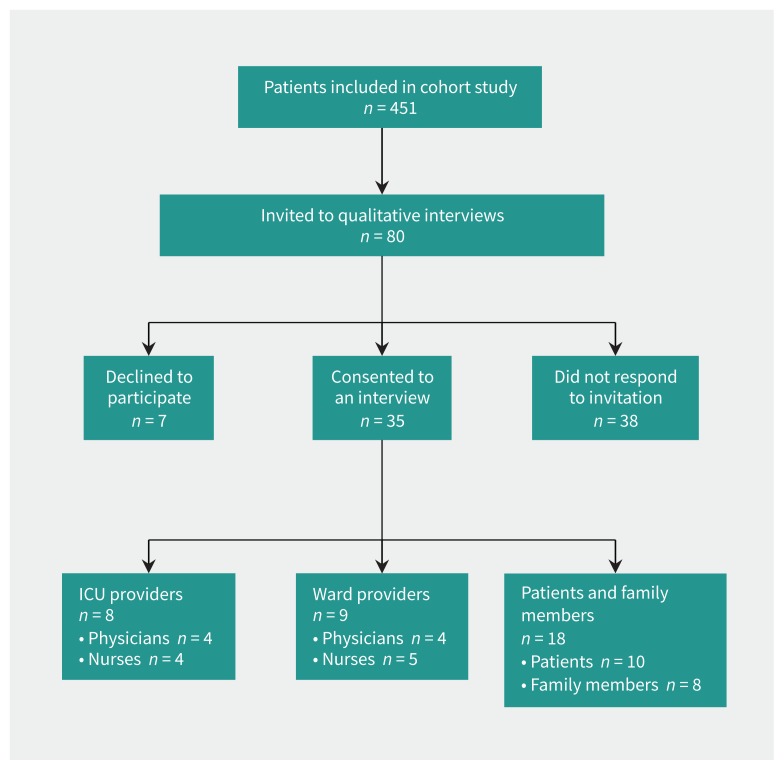

Consecutive consenting patients who were transferred from the ICU to a hospital ward were enrolled in our cohort study. Participants from the cohort study who indicated interest in participating in a follow-up interview were considered for participation. We targeted recruitment of 4 participants (1 patient, 1 family member, 1 ICU provider, 1 ward provider) from each of the 8 English-speaking sites (n = 32) (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170588/-/DC1) to develop our understanding of transfers of care across institutions further (Figure 1). We invited participants by email or telephone depending on contact information they provided when they indicated their interest in the follow-up interview. Although our team was prepared to expand recruitment if necessary, reviewers identified distinct recurring patterns in the data (i.e., barriers, facilitators and recommendations that were identified by participants) with no new themes emerging before the interviews concluded. Thus, no further recruitment was undertaken.15

Figure 1:

Flow diagram of selection of patients for interview.

Data collection

We developed the semistructured interview guide to explore stakeholder experiences with transfers of care from ICU to hospital ward. The interview guide was loosely informed by domains of inquiry identified in a stakeholder survey that we conducted as part of an earlier phase of this research program.14 The interview guide was pilot tested with 9 local stakeholders (4 providers, 5 patient or family members of patients) and refined based on their feedback. After obtaining informed consent from each participant, we (C.D. and Holly Wong, both with experience in conducting qualitative interviewing) conducted private semistructured telephone interviews in an office (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170588/-/DC1). The interviews were concluded by April 2016. Interviews posed questions about participants’ experiences with transfers of care between ICU and hospital ward and their perceptions of perceived barriers and facilitators to high-quality transfers. We audio-recorded and transcribed interviews verbatim.

Qualitative analysis

We used qualitative content analysis16 with Nvivo9 (www.qsrinternational.com/) to analyze interview transcripts and identify themes related to the needs and preferences of 3 categories of participant: patients and their family members, ICU providers (i.e., physicians and nurses), and ward providers (i.e., physicians and nurses) during the transition of care between ICU and hospital ward. Early in the data collection process, 2 experienced researchers (C.D., J.P.L.) analyzed a small sample of the transcripts (n = 5) independently and in duplicate to fracture the data using an open coding methodology,17 identify emerging themes and adjust interview questions and probes to ensure discussion of key themes in subsequent interviews. Researchers met to compare open coding and developed a codebook of emerging themes after they achieved agreement. Each investigator analyzed half of the remaining transcripts using open, axial and selective coding17 to expand and collapse themes. Researchers traded codebooks and analyzed remaining transcripts to ensure that key ideas were not missed. The codebook was iteratively refined using axial coding and finalized by 3 researchers (C.D., J.P.L., J.M.B.). Coded quotes were organized by theme, subtheme and participant type (patient or family member of patient, ICU provider, ward provider).

Ethics approval

The University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board approved this study (Ethics ID no. REB13–0021).

Results

We sent 80 invitations to individuals who had expressed an interest in being contacted for a potential interview. Of these, 35 consented, 7 declined and 38 did not respond. The mean duration of the interviews was 25 minutes (standard deviation: 11 min). Half (51%) of the participants were patients or family members, and the remainder (49%) were ICU and ward providers (Table 1). Nearly two-thirds of the participants (60%) were women (Table 1). Patients and family members were asked to speak about their recent transfer experience from ICU, and providers were encouraged to draw from any of their past experiences with transfers of care from ICU to ward.

Table 1:

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristics | No. of participants* (n = 35) |

|---|---|

| Patient | 10 |

| Family | 8 |

| Intensive care unit provider | 8 |

| Physician | 4 |

| Nurse | 4 |

| Ward provider | 9 |

| Physician | 4 |

| Nurse | 5 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 14 |

| Female | 21 |

Patients and family members opted to be interviewed together at 3 sites, resulting in 35 participants from 32 interviews conducted.

Analysis showed 3 overarching themes describing perceived barriers and facilitators to high-quality transfers of patients: resource availability, communication and institutional culture. Themes were common to all participant groups and characterized by subthemes to capture diversity of participant perspectives. Subthemes described by providers were process oriented (i.e., focused on process, protocol and outcomes), whereas subthemes described by patients and their family members reflected personal experiences. Exemplar quotations for subthemes are illustrated in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2:

Perceived facilitators and barriers to high-quality transfers from ICU to hospital ward, identified by providers

| Theme and subtheme | Facilitators | Barriers | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource availability | |||

| Staff availability | Ward | “What works fairly well is that we as a hospital group are available on a 24-hour basis and we have a good working relationship with the ICU physicians.” Ward provider (Interview 1) | |

| Material resources (e.g., beds, medical record) | Ward | ICU and ward | “… not uncommon situation will be it’s a crunch for beds in the ICU and the ICU fellow (fourth- or fifth-year resident) will call the internal medicine senior (second- or third-year resident) in the evening and say listen we have got this patient here in ICU you have got to come here and transfer them.” Ward provider (Interview 30) |

| Duration of transfer process | ICU and ward | “We tee up the transfer by doing the discharge summary, contacting a service to accept the patient, agreeing on the transfer, and that’s kind of the process. The part that is more variable is that after someone says I accept [the patient] there is often a long delay before they leave the ICU, so that is the part I guess I have less control over or where I feel much can get lost. Because there is a period of time where the patient is physically still under my care but the decision-making is more shared then.” ICU provider (Interview 28) | |

| Timing of transfer (e.g., shift change, at night) | ICU and ward | “Sometimes on my end I have two patients. If somebody is stable enough to be transferred out, I don’t have a whole lot of time to spend with them. I have to get back to my station or if I have an admission waiting in the emergency department than you know, I feel pressed for time.” ICU provider (Interview 22) | |

| Transfer tools | ICU and ward | “At our site we have a transfer record form that details patient name, age, goals of care and certain standard things that should be done and that you should be telling the other nurse so when people from ICU use that and follow along that really well, we really get to know a good picture of the patient. Those are the most successful transfers, when both teams use that form.” Ward provider (Interview 21) | |

| ICU follow-up post transfer | ICU and ward | “We have a medical emergency team that follows up with all of the patients being discharged from ICU just to make sure that the unit has support, that they know if they have questions or if the patient all of a sudden becomes more ill they call the medical emergency team. So it’s a nice bridging program.” ICU provider (Interview 3) | |

| Communication | |||

| Multipronged (e.g., multiple v. singular [or no] forms of communication used) | ICU and ward | ICU and ward | “I think multiple forms of communication need to happen for there to be a well-rounded transfer of care. It’s my expectation that if I am on service [the ICU team] would communicate verbally and in a written note or text message.” ICU provider (Interview 26) |

| Communication between most responsible team members (e.g., attending to attending v. trainee to trainee) | ICU | ICU and ward | “The ultimate report I get about the patient is from my junior resident who has no idea what is going on. They do their best but they don’t really have a good sense of the patient’s trajectory and the major issues and so on. As the internist who is going to take care of the patient, I don’t ever get to talk to someone who actually knows the patient well.” Ward provider (Interview 30) |

| Interprofessional (e.g., communication across professions v. within professions) | ICU and ward | ICU | “I would also let the [receiving nurse] know that outreach was aware of the discharge and that they would follow up with them and that they could call back. I would give them my name and they could call back if they had any questions.” ICU provider (Interview 14) |

| Availability of patient information at point of transfer | Ward | ICU | “… due to the rotational nature of our work, the physician who actually receives the patient may be a different physician [than the accepting physician], and the intensivist at the time of transfer may be different [than the sending physician]. The patient may be transferred in the evening when somebody’s on call and covering. Familiarity is somewhat limited.” ICU provider (Interview 31) |

| Institutional culture | |||

| Patient- and family-centred care | ICU and ward | “We kind of let the families know [about transfers of care] as an afterthought, or the family will call us and we will say oh yeah sorry we transferred that patient.” Ward provider (Interview 29) | |

| Professionalism | ICU | Ward | “… some of the doctors are not willing to do a transfer note. And that does create difficulty for us because we don’t necessarily have the time to dig through every page of the chart to discover what events have transpired and what the decision process was.” Ward provider (Interview 1) |

| Importance placed on transfer by care team | ICU and ward | “People argue that it’s [having sending and receiving teams conduct in-person transfers] impossible because of busy schedules etc., but we need to say no, transfers are a critical component of the care of patients. This is a goal that we should aspire to.” ICU provider (Interview 18) | |

Note: ICU = intensive care unit.

Table 3:

Perceived facilitators and barriers to high-quality transfers from ICU to hospital ward, identified by patients and families*

| Theme and subtheme | Facilitators | Barriers | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource availability | |||

| Staff availability | ✓ | ✓ | “Just knowing that they [ICU providers] were there if there was a problem … they stressed that, I have to say, that there was always somebody going to be available and they were right there.” Patient (Interview 4) |

| Material resources (e.g., beds, medical record) | ✓ | “They said ‘we’re not particularly sure that you are exactly … ready to leave ICU. We’re very sorry, we’ve got a major trauma coming in and you’re doing a whole lot better, we have to move you.’ They just had no beds left.” Family member (Interview 7_2) | |

| Interprofessional collaboration (e.g., social work, physicians, nurses) | ✓ | “The social worker from the trauma unit came down a few days beforehand and told me what unit I would be transferred to and even then she gave a little bit of a rundown on what I should expect.” Patient (Interview 20) | |

| Provider follow-up | ✓ | “I remember a nurse that I had seen previously. I’d been in there for a lengthier stay and she either heard or saw me coming down. She came down to say hello. Just hello, hi, you know, seeing me again. That was really nice, you know. It gives you more of a comfort level. You know, you’re not just a package.” Patient (Interview 5_1) | |

| Patient–provider communication | |||

| Family kept informed | ✓ | “It would’ve been nice if someone could’ve called and explained it [description of transfer process] to me. I couldn’t always be there... I respect that they’re really busy and they’re not necessarily thinking of discussing things with family members.” Family member (Interview 8) | |

| Communication aids (e.g., informational brochure, white board in patient room) | ✓ | ✓ | “It just feels like when you get to unit you’re all by yourself and there hasn’t been any communication from ICU. They don’t know your situation. You have to explain … that’s one of the big things in the hospital, explaining the situation. Sometimes 3, 4, 5, 10 times a day, it feels like.” Family member (Interview 7_2) |

| Ward orientation before transfer | ✓ | “The transfer process was largely, you know, he is physically going to be moved to another ward, the nature of the care will be different, he will be in a four-bed room as opposed to a two-, you know, person room, there will be fewer machines he will be hooked up to. I knew all of that was going to happen, so that wasn’t a surprise. It didn’t feel like a lessening quality of care, it actually felt hopeful because he didn’t have to be in ICU anymore.” Family member (Interview 2_2) | |

| Consistency of information delivered (e.g., variation in what providers say) | ✓ | ✓ | “[The health care staff] will say ‘rumour has it that you will be leaving our care going to a ward’ … You can’t ask people questions when it’s impossible for them know the answer.” Patient (Interview 7_1) |

| Institutional culture | |||

| Role clarity (e.g., stating name and purpose during provider–patient interaction) | ✓ | “So I would have preferred doctors introduce themselves and spell out their name or have a card that you could refer to because it just felt awkward to not know exactly who the doctor was even though you were seeing that person once a day or so.” Family member (Interview 2_2) | |

| Patient education | ✓ | “There were courses to prepare you for physiotherapy and how to get better … . It was very good.” Patient (Interview 9) | |

| Humanization of patient–provider interactions | ✓ | “It was the contact with the people. How the people were with me. That made me feel comfortable. That was the most important thing. And I think that’s why I think I could handle it [the transfer] and why I accepted it, because it was scary, you know? But I was treated like a normal person. Talked to like a normal person.” Patient (Interview 4) | |

| Investment in family well-being | ✓ | “In our second stay [my wife] stayed at one of the hospital facilities; it’s called the outpatient residence. So when I had an emergency, they phoned her and she was probably closer to the ICU than I was at that point. Patient (Interview 7_1) | |

Note: ICU = intensive care unit.

Identified facilitators and barriers were reported as per-participant experience and do not necessarily represent an absolute list.

Overarching themes

1. Resource availability

Availability of resources was a theme that emerged in all participant groups. We define resource availability as the availability of both physical (e.g., bed) and human (e.g., nurses) resources at the levels of the individual patient (e.g., transfer form) and system (e.g., rushed transfer process owing to timing of breaks; Table 2 and Table 3). Provider concerns were consistent with those of patients and family members in 2 key areas: staff availability and material resources. Participants also described subthemes that were unique to their experiences as a provider (n = 4; e.g., transfer tools) or patient or family member of patient (n = 2; e.g., interprofessional collaboration).

2. Communication

Communication was a dominant theme among all participant groups. We define communication as all forms of consultation and documentation about the patient (e.g., verbal, written, text message, face to face, over the phone) as well as who was involved (provider–provider, provider–patient, provider–family) in these exchanges. Providers described subthemes (n = 4) that were largely focused on the importance of circumventing communication breakdowns during transfer from ICU to ward (e.g., multimodal communication), whereas patients and family members described subthemes (n = 4) related primarily to receiving timely and accurate information (e.g., communication aids).

3. Institutional culture

The concept of institutional culture was the third theme that emerged in all participant groups. We defined institutional culture as the norms, beliefs, values and customs that influence processes and protocols within hospital units (Table 2 and Table 3). Providers described subthemes (n = 3) focused on institutional norms that affected their work flow during transitions of care (e.g., importance placed on transfer by care teams), whereas patient and family subthemes (n = 4) concentrated on attitudes in the clinical environment that affected their sense of well-being during a time of vulnerability (e.g., humanization of patient–provider interactions).

Suggestions to improve transfers of care from ICU to ward

Participants were asked to provide suggestions for how to improve transfer from ICU to hospital ward (Table 4). The following were the most common suggestions provided by participants from more than half of the hospitals:

Table 4:

Suggestions to improve transfers from ICU to hospital wards

| Suggestions | ICU providers | Ward providers | Patient or family member of patient | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implement standardized discharge communication tools to ensure continuity of communication between providers and patients and their families (e.g., standardized written summary of patient course in ICU and treatment plan) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | “I like to keep communication [with patients and families] very patient focused, to be explicit … about the main issues. … some sort of written template where we see ‘the main issues of the day included the following’ would be a huge benefit.” ICU provider (Interview 16) |

| Implement standardized discharge communication tools to ensure continuity of communication between providers (e.g., standardized written transfer summary, checklist for verbal handoff) | ✓ | ✓ | “It would be great if we identified a patient for transfer, the team, that might involve [the] doctor and nurse who are going to accept the patient … and the team that has the patient right now, all getting together close to the patient and family having a multidisciplinary sign-over. And ideally that would be facilitated by a standardized checklist with prompts to talk about specific things to the patient, about the domains that are important.” ICU provider (Interview 18) | |

| Use multimodal communication to document transfer and ensure continuity of care (e.g., verbal, written, electronic) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | “Communication between the medical teams in different places should occur as both verbal communication and very detailed written communication about all the current issues, the plan, the follow-up plan, the medications. I think both types of communication are important and complementary.” ICU provider (Interview 18) |

| Develop procedures to manage delays in patient transfer (e.g., scheduled communication updates for patients waiting days for a ward bed) | ✓ | ✓ | “Just because somebody is up for transfer from ICU yesterday doesn’t mean that they just blindly stay up for transfer; it should be evaluated every day.” Ward provider (Interview 29) | |

| Conduct transfer-of-care handover at the patient bedside (e.g., multiprofessional team huddle with ICU and hospital ward teams and handoff at bedside) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | “A family meeting prior to transfer where the former ICU team meets with the new ward team … who are going to be caring for them.” Family member (Interview 24) |

| Ensure necessary resources are available at time of transfer (e.g., bedside nurse for hospital ward available to receive patient) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | “The ward said they were ready … so we brought [the patient] over there but the respiratory therapist … wasn’t prepared, she didn’t think the patient was coming at the time so we were stuck … for about half an hour in the hallway because there was a lot of controversy and push back from different levels of the hospital so that was kind of a miserable transfer.” ICU provider (Interview 3) |

| Actively involve attending physician in the transfer process (e.g., verbal handoff between attending physicians) | ✓ | ✓ | “It wouldn’t be totally unreasonable for the decision about transfer or not transfer to always have to be at least run through over the phone with the internist so they can …go over what they think are the red flags, hear the story, agree that [the transfer] makes sense.” Ward provider (Interview 25) | |

| Ensure essential information is up-to-date at the time of transfer (e.g., current medications and when last administered) | ✓ | ✓ | “It’s hard to find information about when the last time something was given or their med record so it would be nice to go through the meds [with the ICU provider] because sometimes it takes a long time to put together that chart and you are kind of getting late on med times.” Ward provider (Interview 21) |

Note: ICU = intensive care unit.

Implement standardized discharge communication tools to ensure continuity of communication between providers and patients or their families: Patients and providers across all sites stated that implementing a standardized discharge communication tool targeted to patient–provider communication would improve transfers by ensuring continuity of communication. Specific details of the content that should be included in this tool varied across the sites. For example, one provider highlighted the inclusion of the patient’s trajectory and journey in the ICU, whereas a provider at a different site stressed that the tool should prompt conversations about what patients and family members could expect on the ward. Regardless of detail, the perceived level of need for this type of instrument was echoed across participant groups.

Implement standardized discharge communication tools to ensure continuity of communication between providers: Both ICU and ward provider groups across the 8 study sites suggested implementing standardized discharge communication tools. Providers described the importance of discharge communication tools, such as electronic or paper-based tools that travel with the patient during transfer, and the types of information that should be included.

Use multimodal communication to document transfer and ensure continuity of care: Multimodal communication was suggested at 5 sites and across all participant groups. Participants described multimodal communication as verbal communication that is supported with written documentation.

Develop procedures for delays in patient transfer: ICU and ward providers at 5 sites suggested developing procedures to manage delays in patient transfer from ICU (i.e., patients who wait for days for a ward bed). Providers agreed that care must be coordinated and advanced during this period and the patient’s readiness for transfer reassessed daily.

Interpretation

Patient transfers from the ICU are complex events that can disrupt continuity of patient care,2–4,6 yet little is known about the experiences of key stakeholders. Our study provides a multicentre qualitative report of patient, family member, ICU and ward provider perspectives of why transfers of care break down, and how they can be improved to enhance quality of care and improve stakeholder experiences. The in-depth description of stakeholder experiences with transfers of care presented here adds to the existing literature on transfers of care that has largely been developed using quantitative methods.7,12,18 Main findings of the study include the shared assignment by diverse stakeholders of resource availability, communication and institutional culture as main drivers in the breakdown of transfers of care from ICU to ward, and the call for standardized, multimodal communication and transfer procedures to improve quality of care.

Resource availability

Material and human resources were highlighted by participants as both facilitators (i.e., when available) and barriers (i.e., when lacking) to high-quality transfers of care. Previous studies have shown that bed availability can negatively affect transfers from ICU when patients are transferred before they otherwise would be (e.g., owing to an influx of more acute patients).19,20 Conversely, participants in our study also cited long transfer processes as a barrier to high-quality transfers where patients ready for transfer waited days for a hospital ward bed to become available. They reported variable quality of care during this “waiting period” with confusion or a lack of accountability about who is most responsible for the patient.21,22 Health care organizations that have flow failure (i.e., inefficient movement of patients)23 must develop procedures to minimize transfer delays (e.g., mimic just-in-time manufacturing)24 and strategies to ensure patients receive coordinated care while awaiting transfer (e.g., co-management or graduated management).

Communication

Patients, family members and providers described the importance of using multiple modes of communication to support the exchange of information during transfers of care. Verbal and written communication types serve different purposes. Verbal communication can be used to ensure that accurate information is exchanged in a timely manner, but written communication can ensure the durability of patient information over time, preserving the “patient’s story” for all relevant stakeholders (i.e., current status, relevant history, patterns that emerged during care, and future-oriented care plan).25 It is not surprising that patients recovering from a severe illness26 and family members who are under stress may have difficulty remembering details and retaining verbal information.9 Electronic health records that make information27 available to a broad group of stakeholders may provide a platform for multimodal communication.28 For example, some electronic health records have developed mediums for patient–provider communication such as online portals,29 email30 and instant messaging.31 Although promising, concerns remain about confidentiality breaches when using electronic portals to communicate patient information,32 confusion or anxiety when patient information is accessed in the absence of a care provider, 26 and the potential impact on the frequency and length of face-to-face patient–provider interactions.33

Institutional culture

Reconceptualizing the relative importance of transfers of care from ICU to hospital ward (i.e., where transfers are understood as critical to maintaining the continuity of patient care and are prioritized by sending and receiving care teams) was identified as a key facilitator to high-quality transfers.34 What is more, patient- and family-centred care was a facilitator of high-quality ICU transfers. This is important because health care cultures that promote the active involvement of patients and families in partnered care have been shown to alleviate communication barriers, 35 increase psychological well-being,36 preserve continuity of care,35 and improve patient and family perceptions of care received.37 Partnering with patients and their family members during transfers of care from ICU to ward should be considered a high priority by both sending and receiving care teams. To improve transfers of care, they must be recognized as institutional priorities in which patients, patient families and providers all play key roles.

Limitations

There are limitations to consider when interpreting the findings of our study. First, some participants were interviewed up to 2 years after the relevant ICU admission and, thus, recall bias38 might have affected their recollection of events. It is also possible that some perspectives may have been missed, given that participants may have been motivated to interview as a result of a mostly positive or mostly negative experience. Second, this study is limited to the perspectives of providers most responsible for patient care (i.e., physician and nurse) and did not capture the perspectives of other provider groups (e.g., social workers). Nevertheless, the scope of our sample (i.e., perspectives from 6 key stakeholder groups collected from 8 diverse hospital settings across 7 cities and 3 health systems), as well as the distinct likeness of reported perceived barriers, facilitators and recommendations, lead us to believe that our results are applicable to units across the country as factors worth considering in their specific institutional context.

Conclusion

Transitions of care between the ICU and hospital ward are challenging and high risk. Key stakeholders describe 3 overarching themes perceived as barriers or facilitators to high-quality patient transfers: resource availability, communication and institutional culture. Patients and providers have distinct (e.g., process- vs. experience-oriented) but largely overlapping perspectives. They suggest implementing standardized multimodal communication and procedures to manage common delays in patient transfer.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Denise Buchner for her support in developing the interview guide and providing supervision in the collection of data, and Holly Wong for help in conducting interviews. At the time of publication, Jeanna Parsons Leigh is affiliated with the Department of Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, and Division of Critical Care Medicine, Western University, London, Ont.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Sean Bagshaw reports personal fees from Baxter Healthcare, outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Chloe de Grood and Jeanna Parsons Leigh collected and analyzed data and drafted the manuscript; they contributed equally to the work. Sean Bagshaw, Robert Fowler, Peter Dodek, Alan Forster, Jamie Boyd interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Henry Stelfox designed the study, interpreted the data, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Technology Evaluation in the Elderly Network grant number CORE 2013-12A supported this work. Robert Fowler was supported by a personnel award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation, Ontario Provincial Office. Sean Bagshaw was supported by a Canada Research Chair in Critical Care Nephrology. Henry Stelfox was supported by a Population Health Investigator Award from Alberta Innovates and an Embedded Clinician Researcher Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- 1.Singh H, Thomas EJ, Peterson LA, et al. Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:2030–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, Vesin A, et al. OUTCOMEREA Study Group. Selected medical errors in the intensive care unit: results of the IATROREF study: parts I and II. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camiré E, Moyen E, Stelfox HT. Medication errors in critical care: risk factors, prevention and disclosure. CMAJ 2009;180:936–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hua M, Gong MN, Brady J, et al. Early and late unplanned rehospitalizations for survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med 2015;43:430–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAlister FA, Youngson E, Bakal JA, et al. Impact of physician continuity on death or urgent readmission after discharge among patients with heart failure. CMAJ 2013; 185:E681–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons Leigh J, Stelfox HT. Continuity of care for complex medical patients: How far do we go? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:1414–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Häggström M, Bäckström B. Organizing safe transitions from intensive care. Nurs Res Pract 2014;2014:175314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cognet S, Coyer F. Discharge practices for the intensive care patient: a qualitative exploration in the general ward setting. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2014;30:292–300, quiz 301–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field K, Prinjha S, Rowan K. “One patient amongst many”: a qualitative analysis of intensive care unti patients’ experiences of transferring to the general ward”. Crit Care 2008;12:R21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullinane JP, Plowright CI. Patients’ and relatives’ experiences of transfer from intensive care unit to wards. Nurs Crit Care 2013;18:289–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li P, Stelfox HT, Ghali WA. A prospective observational study of physician handoff for intensive-care-unit-to-ward patient transfers. Am J Med 2011;124:860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James S, Quirke S, McBride-Henry K. Staff perception of patient discharge from ICU to ward-based care. Nurs Crit Care 2013;18:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stelfox HT, Parsons Leigh J, Dodek PM, et al. A multi-center prospective cohort study of patient transfers from the intensive care unit to the hospital ward. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:1485–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Reilly M, Parker N. “Unsatisfactory Saturation”: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research”. Qual Res 2012;13:190–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cresswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss AL. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rochester-Eyeguokan CD, Pincus KJ, Patel RS, et al. The current landscape of transitions of care practice models: a scoping review. Pharmacotherapy 2016;36:117–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldfrad C, Rowan K. Consequences of discharges from intensive care at night. Lancet 2000;355:1138–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanane T, Keegan MT, Seferian EG, et al. The association between nighttime transfer from the intensive care unit and patient outcome. Crit Care Med 2008; 36:2232–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams T, Leslie G. Delayed discharges from an adult intensive care unit. Aust Health Rev 2004;28:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexander A. The National Demonstration Hospitals Program. Aust Health Rev 2000;23:198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisognano M. So-called “flow failures” are disrespectful to patients. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2016. Available: www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/flow-failures-are-disrespectful-to-patients (accessed 2016 Dec. 16). [Google Scholar]

- 24.The National Health Service: accident and emergency. The Economist 2016. Sept. 10 Available: www.economist.com/news/britain/21706563-nhs-mess-reformers-believe-new-models-health-care-many-pioneered (accessed 2017 Feb. 9).

- 25.Varpio L, Rashotte J, Day K, et al. The EHR and building the patient’s story: a qualitative investigation of how EHR use obstructs a vital clinical activity. Int J Med Inform 2015;84:1019–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burry L, Cook D, Herridge M, et al. SLEAP Investigators; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Recall of ICU stay in patients managed with a sedation protocol or a sedation protocol with daily interruption. Crit Care Med 2015;43:2180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CI, Langlotz CP, Elmore JG. Implications of direct patient online access to radiology reports through patient web portals. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:1608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Payne TH, Beahan S, Fellner J, et al. Health records all access pass. Patient portals that allow viewing of clinical notes and hospital discharge summaries: the University of Washington Opennotes Implementation experience. J AHIMA 2016;87:36–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright E, Darer J, Tang X, et al. Sharing physician notes through an electronic portal is associated with improved medication adherence: quasi-experimental study. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hassol A, Walker JM, Kidder D, et al. Patient experiences and attitudes about access to a patient electronic health care record and linked web messaging. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:505–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liederman EM, Lee JC, Baquero VH, et al. Patient-physician web messaging. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:52–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruse CS, Argueta DA, Lopez L, et al. Patient and provider attitudes toward the use of patient portals for the management of chronic disease: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leveille SG, Mejilla R, Ngo L, et al. Do patients who access clinical information on patient internet portals have more primary care visits? Med Care 2016;54:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Häggström M, Asplund K, Kristiansen L. Struggle with a gap between intensive care units and general wards. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2009;4:181–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA 2006;296:2848–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Mol MM, Boeter TG, Verharen L, et al. Patient- and family-centred care in the intensive care unit: a challenge in the daily practice of healthcare professionals. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:3212–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gill M, Bagshaw SM, McKenzie E, et al. Patient and family member-led research in the intensive care unit: a novel approach to patient-centered research. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pannucci CJ, Wilkins EG. Identifying and avoiding bias in research. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126:619–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]