Abstract

Background and study aims

Management of post-sleeve gastrectomy fistulas (PSGF) recently has evolved, resulting in prioritization of internal endoscopic drainage (IED). We report our experience with the technique in a tertiary center.

Patients and methods

This was a single-center, retrospective study of 44 patients whose PSGF was managed with IED, comparing two periods: after 2013 (Group 1; n = 22) when IED was used in first line and before 2013 (Group 2; n = 22) when IED was applied in second line. Demographic data, pre-endoscopic management, characteristics of fistulas, therapeutic modalities and outcomes were recorded and compared between the two groups. The primary endpoint was IED efficacy; the secondary endpoint was a comparison of outcomes depending on the timing of IED in the management strategy.

Results

The groups were matched in gender (16 female, 16 male), mean age (43 years old), severity of fistula, delay before treatment, and exposure to previous endoscopic or surgical treatments. The overall efficacy rate was 84 % (37/44): 86 % in Group 1 and 82 % in Group 2 (NS). There was one death and one patient who underwent surgery. The median time to healing was 226 ± 750 days (Group 1) vs. 305 ± 300 days (Group 2) (NS), with a median number of endoscopies of 3 ± 6 vs . 4.5 ± 2.4 (NS). There were no differences in number of nasocavity drains and double pigtail stents (DPS), but significantly more metallic stents, complications, and secondary strictures were seen in Group 2.

Conclusion

IED for management of PSGF is effective in more than 80 % of cases whenever it is used during the therapeutic strategy. This approach should be favored when possible.

Introduction

Digestive fistula remain the main complication of surgery for obesity 1 2 , particularly PSGF, which always occur in the top part of the stapler line. Bariatric surgery represents more than 30 000 interventions per year in France 3 , which is a higher incidence than for surgery for digestive cancer. The rate of morbidity for bariatric surgery is about 10 %, essentially due to postoperative fistulas, with a potential mortality rate between 0.1 % and 5 % 2 4 5 .

Historically, management of PSGF involved closing devices, including endoclips, over-the-scope clips (OTSC) and glue, or derivation devices like self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS). Several studies assessing the efficacy of these techniques have been published. Regarding the closing techniques, OTSC are an interesting way to seal acute orifices measuring up to 20 mm, but they often have be combined with another therapeutic modality to achieve an efficacy rate of 86 % 6 7 8 . Glue injection (cyanoacrylate) is appropriate for simple, unique and narrow fistulas but may be associated with infections 9 10 11 . As for the derivation techniques, the most common is endoscopic stenting, which has an efficacy rate of 70 % but may require several endoscopic sessions 1 12 13 14 15 16 17 . However, the price to pay was a not-negligible rate of complications – especially migration – related to these stents, ranging from 20 % to 50 %, bleeding, ingrowth and more rarely perforations or stripping (6 %) 1 12 13 .

Thus, over the 5 last years, the therapeutic strategy for PSGF has evolved toward IED using both nasocavity drains (NCD) and/or DPS placed throughout the fistula’s orifice. The principle was to guide the drainage towards the gastrointestinal tract while favoring the fistula’s tract occlusion. To date, there are four series that have evaluated this specific approach with very promising success rates, ranging between 78 % and 98 % in three to five endoscopic sessions 18 19 20 21 ( Table 1 ). Consequently, most of the teams experienced in management of complications after bariatric surgery have started applying IED as first line in their therapeutic strategy.

Table 1. Review of the most important series evaluating IED for treatment of PSGF with outcomes.

| Study | n | Median number of endoscopies | Clinical Success | Mean treatment duration (days) | Number of complications | Remarks |

| Pequignot 2012 | 25 | 5 | 84 % | 62 | 1 (ingrowth) | Comp vs SEMS |

| Donatelli 2014 | 21 | 2.9 | 95 % | 55 | 0 | 7 OTSC (2nd line) |

| Donatelli 2015 | 67 | 3.1 | 98 % | 57 | 0 | – |

| Bouchard 2016 | 33 | 3 | 78 % | 47 | 7 (ulcer 3, pain 3, hematoma 1) | – |

| Total | 146 | 3.5 | 91 % | 55 | 5 % |

IED, internal endoscopic drainage; PSGF, post-sleeve gastrectomy fistula; SEMS, self-expandable metallic stent; OTSC, over-the-scope clip

We present results of our series, which evaluated the efficacy of IED either as initial therapy or after classical endoscopic treatment (stents). Our objective was also to confirm the excellent results previously published, increasing the number of cases available in the literature.

Patients and methods

This was a single-center, retrospective, observational study conducted in a tertiary center with large case volume and experience in management of postoperative fistulas.

Patients

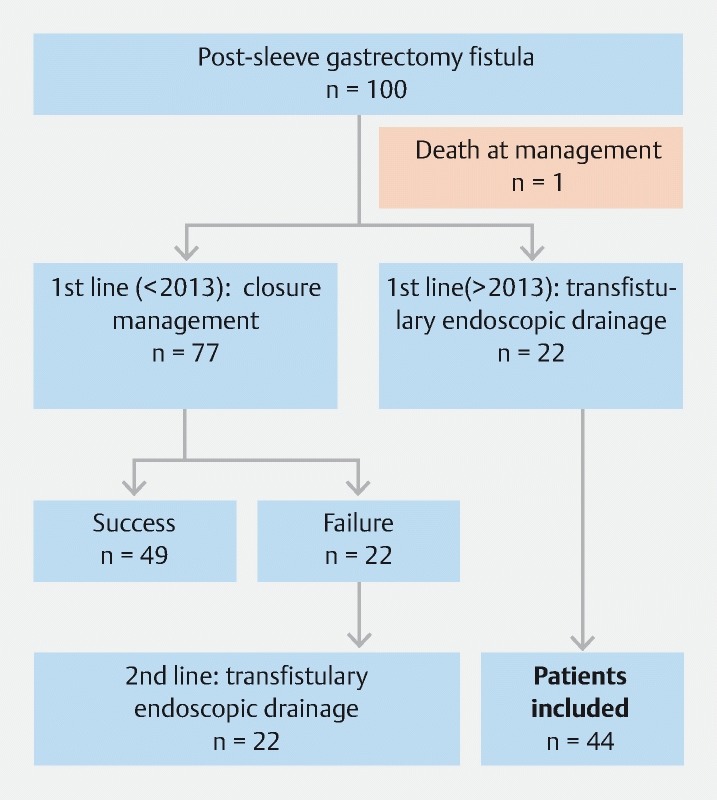

Records in our database from 100 patients managed consecutively for confirmed postoperative fistulas or leakage after bariatric surgery between 2007 and 2015 were examined. Only patients who underwent IED at some point of management, either as first line or after another therapy, were included in the analysis. Two time periods that corresponded to two different strategies for treating PSGF were then identified. The first one, corresponding to Group 1, started after 2013, when IED became the treatment applied as first line in place of SEMS. The second time period, corresponding to Group 2, was before 2013, when closure management (SEMS and/or OTSC) was first-line treatment ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study outlining patient selection based on use of internal endoscopic drainage at one point in management.

For each patient we recorded age; sex; data related to pre-endoscopic management (delay between diagnosis and treatment, attempt at surgical suture, clinical conditions); characteristics of the fistulas/collections (size, paths); modalities of the endoscopic treatment (type and number of sessions); and outcomes (complications, efficacy, time for healing).

Diagnostic and therapeutic modalities

The patients’ fistulas had been suspected clinically based on occurrence of postoperative tachycardia, sepsis, or an increasing purulent flow coming from the surgical drain. The diagnosis was confirmed based on computed tomography showing extra-digestive air and/or a perigastric collection, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy that identified the fistula.

All the therapeutic endoscopies were performed in the endoscopy room on patients under general anesthesia who were intubated and placed in supine position. Each procedure was performed using a large-operating-channel gastroscope (3.8 mm, Pentax, Japan), and with application of CO 2 insufflation (systematically after 2011). Meticulous examination of the mucosa was done to detect the fistula’s primary orifice and contrast media was injected to identify the fistula’s pathway.

Regarding IED, a straight catheter loaded with a guidewire was advanced into the collection. Then, if the cavity was adequately drained surgically, one or two DPS were placed (plastic 7- or 10-cm long 7F stents; Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States). The purpose was threefold: first, to help drain the cavity; second, to obstruct the fistula’s orifice and enable oral intake; and third, to induce mechanical reepithelialization along the fistula’s pathway. Conversely, if the collection was not correctly drained (flow of pus), a NCD was placed in addition to one DPS to wash the infected cavity. Then, patients started oral alimentation followed by systematic flushing of the drain with 20 to 30 mL of saline after each meal. The NCD was kept in place for 1 month but patients were discharged after 1 week. After 1 month, patients underwent computed tomography (CT) scan and subsequent endoscopy to assess the fistula and eventually remove the drain. The DPS were then left in place for 6 months before final removal.

The primary objective of the study was to assess efficacy of NCD in both groups. Efficacy was defined as healing of the fistula, confirmed by absence of residual leak at endoscopy, absence of residual fluid collection on CT scan, and absence of clinical recurrence after 6-month follow-up. Healing time was calculated based on this definition. Secondary objectives were to document complications related to this treatment and evaluate its final efficacy, time for healing and duration of endoscopic treatment in the two groups depending on at which point in the management strategy IED was used.

Results

Demography and pre-endoscopic management

Among patients referred to our center for PSGF, 44 were managed with IED at some point (22 in each group) and were included for analysis. The characteristics of the patients and fistulas are presented and compared in Table 2 . The two groups were comparable in terms of gender (16 women and 6 men per group) and mean age: 42.7 ± 11.4 versus 43.7 ± 13.8 years. The severity of their clinical conditions was comparable because there were an equal number of patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit or suffering from severe sepsis in each group.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients and endoscopic management at time of management in our center.

| Characteristics | Group 1 IED 1 st line | Group 2 IED 2 nd line | P value |

| Age | 43 ± 11 | 43 ± 14 | 0.91 |

| Sex | 16F – 6 M | 16F – 6 M | NA |

| External prior management | 41 % | 45 % | 0.76 |

| Management < 30 days | 62 % | 56 % | 0.75 |

| ICU at management | 33 % | 14 % | 0.14 |

| Prior surgical suture attempt | 65 % | 63 % | 0.9 |

| Surgical drain | 14 % | 52 % | 0.009 |

| Fistula characteristics | |||

| Collection | 100 % | 68 % | 0.02 |

| Collection > 5 cm | 81 % | 60 % | 0.14 |

| Pus | 95 % | 57 % | 0.004 |

| Primary orifice > 5 mm | 86 % | 86 % | 1 |

| Bronchial fistula | 4.5 % | 4.5 % | 1 |

| Rosenthal Classification | |||

| Acute | 3 (14 %) | 0 | NA |

| Early | 14 (63 %) | 9 (41 %) | NA |

| Late | 3 (14 %) | 7 (32 %) | NA |

| Chronic | 2 (9 %) | 6 (27 %) | NA |

IED, internal endoscopic drainage; ICU, intensive care unit

Regarding pre-endoscopic management, there was no difference in the number of patients who underwent previous endoscopy at another center. However, patients were referred earlier in Group 1 than in Group 2 (before 2013) since 63 % vs 41 %, respectively, were managed “early” according to the Rosenthal classification ( Table 2 ). After applying IED, there was no further surgical repair (suturing) in either group; however, surgical drainage was performed statistically significantly more often in Group 2: 14 % vs. 52 %, respectively; P = 0.09.

Presence of a collection and flow of pus were more often noticed in Group 1 than in Group 2: 100 % vs. 68 % ( P = 0.02) and 95 % vs . 57 % ( P < 0.05), respectively. Finally, there was no difference in mean size of the fistulas’ primary orifices and an association with bronchial fistula.

Characteristics and outcomes of the endoscopic treatment

Overall efficacy of IED in management of PSGF was 84 % (37/44 patients). There was no difference depending on whether the treatment was applied as first line (Group 1) or as second line (Group 2), since the efficacy rates were 86 % and 82 %, respectively. The results are summarized in Table 3 . One death (2.3 %) occurred in Group 2, which was unrelated to the endoscopy itself, and one patient underwent a total gastrectomy because of failure of treatment. The other patients were lost to follow-up while endoscopic management was ongoing, so we considered their treatment as having failed.

Table 3. Outcomes of IED depending on its place in the therapeutic strategy.

| Outcomes | Group 1 IED 1 st line | Group 2 IED 2 nd line | P value |

| Early rehospitalization | 17 % | 47 % | 0.1 |

| Complications after first endoscopy | 4.7 % | 47 % | 0.02 |

| Delayed stricture | 4.8 % | 26 % | 0.06 |

| Death | 0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Median number of endoscopies | 3 ± 6 | 4.5 ± 2.4 | NS |

| Median time for healing (days) | 226 ± 750 | 305 ± 300 | NS |

| Final efficacy | 86 % | 82 % | NS |

IED, internal endoscopic drainage

Median time for healing was 226 ± 750 days in Group 1 versus 305 ± 300 days in Group 2, including 6-month follow-up without recurrence. Median number of endoscopies was 3 ± 6 vs . 4.5 ± 2, respectively. These results were not statistically significant ( P > 0.05). However, there were more overall complications observed when IED was used as second-line treatment (Group 2). Indeed, the complication rate after the first endoscopic treatment, including bleeding, migration or perforations, was significantly higher (47 % vs . 4.7 %, respectively), mostly due to SEMS. Moreover, delayed strictures were more frequently observed during follow-up (26 % vs. 4.8 %, respectively) and patients were more often re-hospitalized in Group 2 (47 % vs . 17 %, respectively).

Finally, regarding device use during endoscopic management ( Table 4 ), SEMS and OTSC (Ovesco, Germany) were more often used in Group 2. When management with IED started, the mean number of NCD and DPS placed was not statistically different between the two groups.

Table 4. Characteristics of endoscopic management according to device used in both groups.

| Characteristics | Group 1 NCD 1 st line | Group 2 NCD 2 nd line | P value |

| SEMS | 36 % | 86 % | 0.04 |

| OTSC | 23 % | 82 % | 0.0001 |

| Double pigtail stent | 81 % | 86 % | 0.4 |

| Nasocavity drain | 68 % | 54 % | 0.4 |

| Glue | 18 % | 23 % | 0.7 |

| Total number of NCDs | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 0.8 ± 1 | 0.2 |

| Total number of DPS | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.4 |

NCD, nasocavity drain, SEMS, self-expandable metallic stent; OTSC, over-the-scope clip; DPS, double pigtail stent

Discussion

Over the past 5 years, endoscopic management of fistulas complicating bariatric surgery evolved dramatically toward IED. Indeed, classical management, mainly based on metallic stents, is associated with a significant rate of complications and rates of efficacy higher than 70 % cannot be achieved, no matter the type of stent used and even when combined with a closing system 1 7 12 14 17 22 23 . Thus, IED has been applied more and more by teams involved in management of PSGF. Indeed, in an early experience, we previously demonstrated that use of NCD and DPS allowed for patients to be discharged earlier with oral refeeding, provided that the drain is rinsed after each meal 13 . More recently, use of the endovacuum (Endosponge) has been described with promising results, but further evaluation is required and use of the device is still limited to the upper gastrointestinal tract 24 25 26 . Finally, Shnell et al. described an endoscopic approach combining septotomy and sleeve stricture dilation for treatment of late/chronic leaks in 10 patients, with interesting outcomes 27 .

Surprisingly, there are only four published series in which IED for PSGF has been specifically evaluated, in a total of 146 patients 18 19 20 21 . When pooling these data, internal management reaches an efficacy rate of 91 %, in a median of three to five endoscopies, a mean time for healing of about 6 months and a very low complication rate of around 5 %. Donatelli et al. suggested that associating IED with another treatment remains possible, because in his series, seven patients underwent successful OTCS placement as second-line therapy 19 . Pequignot et al. also demonstrated that, compared with SEMS, IED reduces the number of procedures, morbidity, and time to healing 20 .

By involving 44 patients, our series is one of the largest currently available in the literature, specifically describing changes regarding IED placement over time. We intended to provide information about outcomes of IED depending upon when in the therapeutic strategy it was performed, in a real-life setting with case-consecutive patients over 7 years. The overall efficacy reached (84 %) was consistent with the literature, as was the median number of endoscopies. Very interestingly, efficacy was comparable whether IED was performed as first-line treatment (Group 1, 86 %) or after prior therapy (Group 2, 82 %), even if pus and collections were more common. Also, the clinical condition of patients was the same in both groups at the time of first endoscopy, despite differences in their previous management. Indeed, in Group 1, fewer patients had undergone prior surgical drainage but they were referred earlier than those in Group 2. In the latter group, drainage was performed more often. These differences may explain why our results did not demonstrate differences in terms of sepsis and hospitalizations in the intensive care unit between the two groups.

In our series, overall risk of complications, particularly those related to SEMS, including bleeding, migration, ingrowth, and perforations, was significantly decreased. Time to healing may be surprising, but that was a matter of definition, as explained in the methods section. We achieved a healing time of 226 ± 750 days in Group 1, which was lower than in Group 2, including the 6-month (180 days) follow-up. Excluding follow-up time, healing time at endoscopy was 46 days, which is consistent with reports in the literature.

Finally, this study demonstrates that IED has an important role to play at any point in the therapeutic algorithm, with the same clinical success. We intended to provide a therapeutic algorithm for management of PSGF, depending on the situations encountered ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Algorithm outlining the strategy for PSGF management depending on presence of surgical drainage and size of the primary orifice and collection.

Conclusion

In conclusion, even if prospective studies are necessary to confirm these data, probably with a larger sample of patients, IED currently should be considered first-line treatment for PSGF. The approach offers clinical efficacy rates of more than 80 % with low complication rates, and may allow patients to achieve early realimentation.

Footnotes

Competing interests Prof. Barthet is a consultant for Boston Scientific.

References

- 1.Moszkowicz D, Arienzo R, Khettab I et al. Sleeve gastrectomy severe complications: is it always a reasonable surgical option? Obes Surg. 2013;23:676–686. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0860-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal R J, International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel, Diaz A A et al. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of > 12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basdevant A, Coupaye M, Charles M A. Paris: Arnette; 2004. Définition, épidémiologie, origines, conséquences et traitement des obésités de l'adulte; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E et al. Bariatric Surgery. JAMA. 2004;292:1724. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuks D, Verhaeghe P, Brehant O et al. Results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A prospective study in 135 patients with morbid obesity. Surgery. 2009;145:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voermans R P, Le Moine O, von Renteln D et al. Efficacy of endoscopic closure of acute perforations of the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercky P, Gonzalez J-M, Aimore Bonin E et al. Usefulness of over-the-scope clipping system for closing digestive fistulas. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:18–24. doi: 10.1111/den.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surace M, Mercky P, Demarquay J-F et al. Endoscopic management of GI fistulae with the over-the-scope clip system (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1416–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonanomi G, Prince J M, McSteen F et al. Sealing effect of fibrin glue on the healing of gastrointestinal anastomoses: implications for the endoscopic treatment of leaks. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1620–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8803-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papavramidis T S, Kotzampassi K, Kotidis E et al. Endoscopic fibrin sealing of gastrocutaneous fistulas after sleeve gastrectomy and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1802–1805. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papavramidis S T, Eleftheriadis E E, Papavramidis T S et al. Endoscopic management of gastrocutaneous fistula after bariatric surgery by using a fibrin sealant. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:296–300. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02545-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisendrath P, Cremer M, Himpens J et al. Endotherapy including temporary stenting of fistulas of the upper gastrointestinal tract after laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Endoscopy. 2007;39:625–630. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bège T, Emungania O, Vitton V et al. An endoscopic strategy for management of anastomotic complications from bariatric surgery: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Boeckel P GA, Dua K S, Weusten B LAM et al. Fully covered self-expandable metal stents (SEMS), partially covered SEMS and self-expandable plastic stents for the treatment of benign esophageal ruptures and anastomotic leaks. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puig C A, Waked T M, Baron T H et al. The role of endoscopic stents in the management of chronic anastomotic and staple line leaks and chronic strictures after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murino A, Arvanitakis M, Le Moine O et al. Effectiveness of endoscopic management using self-expandable metal stents in a large cohort of patients with post-bariatric leaks. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1569–1576. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez J-M, Garces Duran R, Vanbiervliet G et al. Double-type metallic stents efficacy for the management of post-operative fistulas, leakages, and perforations of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2013–2018. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3904-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donatelli G, Ferretti S, Vergeau B M et al. Endoscopic internal drainage with enteral nutrition (EDEN) for treatment of leaks following sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1400–1407. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donatelli G, Dumont J L, Cereatti F et al. Treatment of leaks following sleeve gastrectomy by endoscopic internal drainage (EID) Obes Surg. 2015;25:1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pequignot A, Fuks D, Verhaeghe P et al. Is there a place for pigtail drains in the management of gastric leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy? Obes Surg. 2012;22:712–720. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0597-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouchard S, Eisendrath P, Toussaint E et al. Trans-fistulary endoscopic drainage for post-bariatric abdominal collections communicating with the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2016;48:809. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-108726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swinnen J, Eisendrath P, Rigaux J et al. Self-expandable metal stents for the treatment of benign upper GI leaks and perforations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:890–899. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Mourad H, Himpens J, Verhofstadt J. Stent treatment for fistula after obesity surgery: results in 47 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:808–816. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leeds S G, Burdick J S. Management of gastric leaks after sleeve gastrectomy with endoluminal vacuum (E-Vac) therapy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1278–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smallwood N R, Fleshman J W, Leeds S G et al. The use of endoluminal vacuum (E-Vac) therapy in the management of upper gastrointestinal leaks and perforations. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2473–2480. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bludau M, Hölscher A H, Herbold T et al. Management of upper intestinal leaks using an endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure system (E-VAC) Surg Endosc. 2014;28:896–901. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3244-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shnell M, Gluck N, Abu-Abeid S et al. Use of endoscopic septotomy for the treatment of late staple-line leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Endoscopy 2017. 49:59–63. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-117109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]