Abstract

Background and study aims

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an effective treatment for pancreaticolithiasis, including use of pancreatoscopy for intraductal electrohydraulic lithotripsy (IEHL). Pancreatoscopy is often limited by a small-caliber downstream pancreatic duct as well as an unstable pancreatoscope position within the pancreatic head. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreaticogastrostomy (EUS-PG) has been developed as a method to relieve ductal obstruction when retrograde access fails. The current study describes pancreatoscopy via EUS-PG, a novel method for managing obstructing pancreaticolithiasis.

Patients and methods

From September 2017 to January 2018, patients who underwent EUS-PG followed by antegrade pancreatoscopy via PG were identified. Endoscopy reports, medical charts and relevant laboratory data were reviewed and recorded.

Results

Five patients underwent EUS-PG and antegrade pancreatoscopy via PG during the study period; clinical success rate was 100 %. There were no significant adverse events during the procedure or follow up period.

Conclusions

Pancreatoscopy via PG for IEHL is safe and effective for treating obstructing pancreaticolithiasis in patients who have previously failed ERCP or in clinical scenarios were ERCP is not possible.

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is effective for treatment of chronic pancreatitis 1 , including use of pancreatoscopy for intraductal electrohydraulic lithotripsy (IEHL) and stone removal 2 3 4 . Pancreatoscopy is limited by the often-small-caliber downstream pancreatic duct (PD) and unstable pancreatoscope position within the pancreatic head. Ansa pancreatica, when present, can prevent access to upstream stones. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreaticogastrostomy (EUS-PG) has been used to relieve ductal obstruction when retrograde access fails 5 6 . In this study, we describe application of pancreatoscopy via EUS-PG for treatment of obstructing pancreaticolithiasis in patients who failed conventional therapy.

Patients and methods

Patients

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted in a tertiary referral center in the United States. From September 2017 to January 2018, all patients who underwent EUS-PG followed by antegrade pancreatoscopy by one endoscopist in the setting of obstructing pancreaticolithiasis after failed ERCP were identified. Endoscopy reports, medical charts and relevant laboratory data were reviewed and recorded in accordance with Institutional Review Board protocol. Clinical and procedural data were collected, including etiology of pancreatic disease, indication for procedure, endoscopic data (procedure duration and findings), procedure-related adverse events, post-procedural symptoms, and clinical success, when available.

Procedure

Cross-sectional imaging in the form of computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging was obtained in all patients. EUS-PG was performed under general anesthesia. A linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT180, Olympus America, Center Valley, Pennsylvania, United States) was positioned in the stomach and the main PD punctured with a 19G needle (Expect, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts, United States). A 0.025”, 450-cm guidewire (VisiGlide, Olympus) was passed antegrade into the PD. The tract was dilated and one (one patient) or two (four patients) plastic pancreatic stents (Zimmon, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States) with a pigtail on the gastric side and straight or pigtail on the opposite end were placed, into the duodenum or just upstream to the obstructing stone if the guidewire could not be advanced into the duodenum; we preferred to pass the distal ends of the stent into the duodenum whenever possible to anchor the stents and prevent outward migration into the stomach. When more than one stent was placed we secured two guidewires before the first stent was placed by using a cytology brush catheter (RX Cytology Brush, Boston Scientific) with the brush removed to accommodate the second guidewire, since when re-cannulating the wire would pass between the stomach wall and the pancreas and not into the duct. Subsequent ERCP was performed using a standard duodenoscope (Olympus); the pancreatic duct was easily cannulated alongside the indwelling stent(s) and a guidewire placed into the duct. The stent was removed by passing a snare or grasping device alongside the wire to maintain access. PG dilation was followed by antegrade passage of a digital cholangiopancreatoscope (SpyGlass DS, Boston Scientific). IEHL was administered through a 1.9 Fr-(0.63 mm) probe (AUTOLITH, Northgate Technologies, Inc., Elgin, Illinois, United States) passed down the working channel of the cholangiopancreatoscope, with shocks applied at 80 to 100 J (AUTOLITH in three and AUTOLITH Touch in two), 10 to 20 shocks per pulse, as previously described 2 . Stone fragments were removed using baskets and balloons, and underlying PD strictures treated. Fig. 1 demonstrates a sequence of images in one of the typical patients treated.

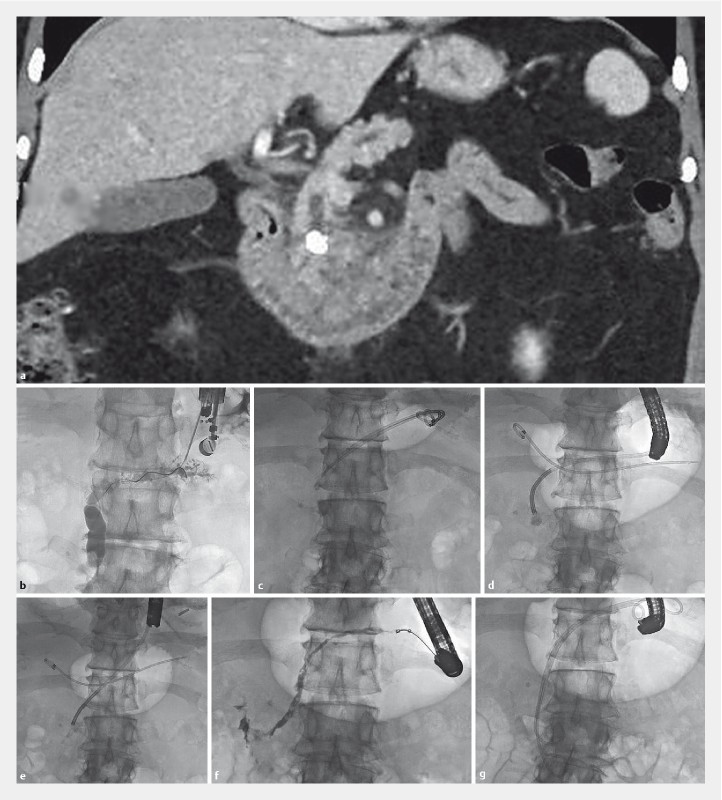

Fig. 1 a.

Coronal CT scan image showing intraductal obstructing pancreatic head stone. b Radiographic image during EUS-guided pancreaticogastrostomy. Guidewire is advanced through a 19G needle into the duct. c Radiographic scout image at follow-up ERCP showing PG stents within the duct. d Radiographic image of pancreatoscope dvanced to the level of the stone. Note one of the prior PG stents is free in the stomach overlying the image. e Radiographic image after stone fragmentation, f Follow-up antegrade pancreatogram showing free flow into the duodenum. g Radiographic image showing two double pigtail transgastric/transpapillary 7Fr stents placed.

Definitions and classifications

In this study, technical success was defined as transgastric pancreatic stent placement followed by stent removal and antegrade pancreatoscopy. Adverse events were graded according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy lexicon 7 .

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, Texas, United States). All continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and skewed variables are expressed as median and interquartile range. Categorical variables are expressed as proportions (%).

Results

Patient characteristics

Five patients meeting inclusion criteria were identified during the study period; three men, median age 65 (Interquartile range 59, 69). All five patients had previously failed ERCP for treatment of pancreaticolithiasis, three due to failure to cannulate the PD and two due to inability to advance a guidewire beyond the obstruction. In one patient a rendezvous maneuver was attempted unsuccessfully as the guidewire could not be advanced beyond the stone into the duodenum. All patients had obstructing pancreaticolithiasis. Patient demographics are described in Table 1 .

Table 1. Patient demographics.

| Pancreatoscopy via pancreaticogastrostomy (n = 5) | ||

| Median age (SD) | 62.8 | 28.1 |

| Women | 2 | |

| Ansa pancreatica present, n (%) | 2 | 40 % |

| Stricture present, n (%) | 2 | 40 % |

|

1 | 20 % |

|

1 | 20 % |

| Mean stricture length, mm (SD) | 17.50 | 3.54 |

| Pancreatic duct stones present, n (%) | 5 | 100 % |

| Mean size of stone in largest diameter, mm (SD) | 8.99 | 3.32 |

| Prior unsuccessful ERCP | 5 | |

| Reason for prior unsuccessful ERCP | ||

|

3 | |

|

2 | |

| Rendezvous attempted | 1 | |

Pancreaticogastrostomy

EUS-PG was technically successful in all patients. When failed ERCP and EUS-PG were performed in the same session, mean procedure time was 114.8 min (SD ± 27 min). When EUS-PG only was performed, mean procedure time was 102.3 min (SD ± 20 min). The PG was balloon dilated to 4 mm and one or more 15-cm double pigtail stent (5 or 7 Fr) was placed from the stomach into the PD. All patients were discharged the same day. Antegrade pancreatoscopy was delayed in all cases to allow tract maturation.

ERCP and antegrade pancreatoscopy

Antegrade pancreatoscopy was performed at a mean number of 56.4 days after PG creation. PG stents were removed and the tract dilated to a mean of 6.4 mm (SD ± 0.89 mm). IEHL was performed and completed in a single session. Four patients had a single obstructing stone and one had multiple obstructing stones. Stone fragments were extracted transduodenally in two patients and transgastrically through the PG in three. Two patients had ansa pancreatica and two patients had PD strictures (one dorsal, one ventral). In one patient with a severe ventral PD stricture, a fully-covered metal stent was placed. In the other patients, plastic PD stents were placed across the papilla. No adverse events occurred during either PG creation or pancreatoscopy; clinical success was achieved in all. Patients were followed clinically for signs and symptoms of recurrent stone disease, with no evidence on follow-up. Procedure and outcomes data are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2. Procedure and outcomes data.

| Pancreatoscopy via pancreaticogastrostomy (n = 5) | ||

| Pancreaticogastrostomy creation | ||

| Outpatient case, n (%) | 5 | 100 % |

| Mean procedure time, minutes (SD) | 112.72 | 24.74 |

| Failed ERCP and PG Creation in same session, n (%) | 2 | 40 % |

| Needle knife used, n (%) | 2 | 40 % |

| Mean dilation diameter prior to PG, mm (SD) | 4.00 | 0.00 |

| Mean PG stent diameter, Fr (SD) | 6.60 | 0.89 |

| One plastic stent placed across PG, n (%) | 1 | 20 % |

| Two plastic stents placed across PG, n (%) | 4 | 80 % |

| Pancreatoscopy via PG | ||

| Mean time between procedures, days (SD) | 56.40 | 33.78 |

| Mean PG tract dilation diameter following PG stent removal, mm (SD) | 6.40 | 0.89 |

| Single lithotripsy session, n (%) | 5 | 100 % |

| Stone removed antegrade through papilla, n (%) | 2 | 40 % |

| Stone removed retrograde through PG, n (%) | 3 | 60 % |

| Clinical outcome | ||

| Patients with clinical success, n (%) | 5 | 100 % |

| Patients with unplanned surgical intervention, n (%) | 0 | 0 % |

| Deaths during follow up period, n (%) | 0 | 0 % |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PG, pancreaticogastrostomy; SD, significant deviation

Discussion

Therapeutic EUS for management of obstructive pancreaticobiliary disorders continues to evolve. EUS-guided pancreaticogastrostomy was first described in 2002 by François et al. and has been used for relief of PD obstruction in patients with both native and surgically altered anatomy 8 9 . However, PG followed by antegrade pancreatoscopy and intraductal electrohydraulic lithotripsy has not been described.

In our center, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is not available for fragmentation of PD stones. For patients with obstructing PD stones less than 15 mm and overall minimal intraductal stone burden, we perform stone removal via ERCP with or without pancreatoscopy. We adopted EUS-PG for antegrade access to treat obstructing pancreatic stones when ERCP failed. Notably, in two of our patients, presence of an ansa pancreatic loop prevented access to the stones from a retrograde approach, and in these two patients we rerouted the main PD drainage antegrade through the minor papilla.

Conclusion

We believe EUS-guided pancreaticogastrostomy followed by antegrade pancreatoscopy and intraductal lithotripsy is useful for a subset of patients with symptomatic obstructing pancreatic head stones when conventional ERCP fails.

Footnotes

Competing interests Dr. Baron is a consultant and speaker for Boston Scientific, W.L. Gore, Cook Endoscopy and Olympus America. Dr. James receives research and training support in part by a grant from the NIH (T32DK007634).

References

- 1.Clarke B, Slivka A, Tomizawa Y et al. Endoscopic therapy is effective for patients with chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekkali N L, Murray S, Johnson G J et al. Pancreatoscopy-directed electrohydraulic lithotripsy for pancreatic ductal stones in painful chronic pancreatitis using SpyGlass. Pancreas. 2017;46:528–530. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyna T, Neuhaus H, Gerges C. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct stones under direct vision: revolution or resignation? Systematic review. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:29–37. doi: 10.1111/den.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attwell A R, Brauer B C, Chen Y K et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with per oral pancreatoscopy for calcific chronic pancreatitis using endoscope and catheter-based pancreatoscopes: a 10-year single-center experience. Pancreas. 2014;43:268–274. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182965d81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Tsuchiya T et al. Initial evaluation of a new plastic pancreatic duct stent for endoscopic ultrasonography-guided placement. Endoscopy. 2015;47:462–465. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhir V, Isayama H, Itoi T et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary and pancreatic duct interventions. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:472–485. doi: 10.1111/den.12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton P B, Eisen G M, Aabakken L et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.François E, Kahaleh M, Giovannini M et al. EUS-guided pancreaticogastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:128–133. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ergun M, Aouattah T, Gillain C et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transluminal drainage of pancreatic duct obstruction: long-term outcome. Endoscopy. 2011;43:518–525. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]