Abstract

Background

Little is known about quality of life after bladder cancer treatment. This common cancer is managed using treatments that can affect urinary, sexual and bowel function.

Methods

To understand quality of life and inform future care, the Department of Health (England) surveyed adults surviving bladder cancer 1–5 years after diagnosis. Questions related to disease status, co-existing conditions, generic health (EQ-5D), cancer-generic (Social Difficulties Inventory) and cancer-specific outcomes (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Bladder).

Results

In total, 673 (54%) patients responded; including 500 (74%) men and 539 (80%) with co-existing conditions. Most respondents received endoscopic treatment (60%), while 92 (14%) and 99 (15%) received radical cystectomy or radiotherapy, respectively. Questionnaire completion rates varied (51–97%). Treatment groups reported ≥1 problem using EQ-5D generic domains (59–74%). Usual activities was the most common concern. Urinary frequency was common after endoscopy (34–37%) and radiotherapy (44–50%). Certain populations were more likely to report generic, cancer-generic and cancer-specific problems; notably those with co-existing long-term conditions and those treated with radiotherapy.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates the importance of assessing patient-reported outcomes in this population. There is a need for larger, more in-depth studies to fully understand the challenges patients with bladder cancer face.

Subject terms: Bladder cancer, Cancer epidemiology

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is the 9th most common cancer in the United Kingdom and one of the most expensive malignancies to manage.1,2 The disease is best stratified according to the presence of muscle invasion and cellular differentiation. Most BCs are non-muscle invasive (NMIBC) and have an excellent long-term prognosis.3 NMIBC tumours are managed by endoscopic resection, intravesical chemotherapy and long-term surveillance.4 Following initial treatment, many patients develop local recurrence, requiring further treatments.5 Around 1/3 of tumours are muscle invasive BCs (MIBCs), requiring radical treatment if cure is to be obtained. Radical cystectomy (RC) or radiotherapy includes treatment of adjacent viscera with regional lymph nodes, and often includes systemic chemotherapy. The nature and toxicity of treatments and surveillance for BC can vary between patients, between each option and over time. There is evidence that treatment for MIBC can impact upon urinary function,6 bowel function,7 sexual function,8,9 and affects body image,10,11 which can lead to anxiety and depression.7 However, there is less evidence regarding the consequences of treatment for NMIBC and the impact on patients' Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL).12,13

The importance of large scale, population-level Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS) in improving healthcare design, patient experience and directing care is becoming recognised.14,15 PROMS can be used to ascertain a more comprehensive understanding of the quality of survival, alongside the impact and relevance of health care provision, and as a surrogate measure within clinical trials. Previous research in the USA used a linkage database to identify BC patients and looked at results of 620 surveys completed before diagnosis and 856 completed after by patients ≥65 years old.16 European PROMs work included 823 German patients of all ages and stages of BC.13 These cross-sectional studies used generic PROMs or generic cancer PROMs.

To date, no large-scale surveys of BC patients have been conducted in the United Kindgom. As such, in 2013 the Department of Health (DH) England designed and administered a pilot survey of patients 1–5 years following their initial treatment for BC. Here we report the results of the pilot survey, which was conducted to identify a methodology to define the HRQL of individuals in the years following their treatment and to identify potential factors associated with poor outcomes.

Methods

Survey design

The DH methodology has been described previously for cohorts diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, breast, colorectal and prostate cancer.17 Individuals aged 16 or older surviving 1–5 years after a diagnosis of BC were identified via the Eastern Cancer Registration and Intelligence Centre (now part of National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service, NCRAS).18 The sample size was chosen to match similar studies performed by the DH in other cancer sites.17

Identified participants were mailed a questionnaire, with a covering letter from their treating Cancer Centre. Consent to participate was implied through return of completed questionnaires. Individuals who did not want to participate were asked to return their questionnaire uncompleted or to discard the survey. Two reminders were sent to non-responders. A Freephone helpline for patients was provided, which supported completion of the survey. Permission to approach patients without informed consent was given by the Health Research Authority (ref ECC 5-02(FT7)/2012).

Survey content

Survey content included questions about treatment, disease status, generic HRQL (EQ-5D-5L) and BC specific outcomes (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Bladder (FACT-Bl)), social problems (Social Difficulties Inventory (SDI-21)), health and well-being in the past month, experience of care and presence of other long-term conditions (LTCs) (Supplementary File 1).

The EQ-5D-5L records problems on five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression).19,20 There are five response options ranging from no problems to extreme problems. Respondents are asked to complete the response options based on how they are feeling that day.

The SDI-21 is a 21-item questionnaire, developed to assess everyday problems experienced by cancer patients.21 Questions are answered on a scale of 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (very much), with respect to the past month. Sixteen of the items form three subscales: Everyday Living, Money Matters and Self and Others. These scales form a measure of social distress (SD-16), with scores ranging from 0 to 44.22 The SDI-21 also comprises five single items.

FACT-Bl consists of the 27-item FACT-General (FACT-G) questionnaire23 and 13 additional items. FACT-G covers four areas; Physical well-being, Social/family well-being, Emotional well-being and Functional well-being. The 13 additional items relate to urinary issues, bowel issues, appetite and weight, sexual items, body image, a question asking if the respondent has an ostomy appliance and two questions about ostomy appliances. All items ask about the last 7 days.

These surveys were chosen for inclusion as EQ-5D-5L, SDI-21 and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) modules have been used in similar studies performed by the DH in other cancer sites.17,14 Cognitive testing of all questionnaires was performed with a group of volunteer patients and expert panel review (clinicians/methodologists). In the final version of the survey, the team designing the survey removed the 'somewhat' response option from FACT-Bl; changing the questionnaire from five responses to four.18

Data handling

All variables were derived from the survey data. Participants were asked if they had any other LTCs at the time of completing the questionnaire and to tick all conditions that they had from a list widely used in English DH surveys. This variable was categorised into none, 1, 2 or ≥3 LTCs. Information on self-reported disease status (in remission, treated but still present, not treated, recurrence, and not certain) and treatments (endoscopic/telescopic surgery with or without chemotherapy directly into the bladder, RC, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) was taken from the questionnaire. Age was grouped into <55 years, 55–64 years, 65–74 years, 75–85 years and ≥85 years.

EQ-5D-5L responses were split into people who reported at least one problem (of any severity) on any domain and people who reported having no problems on any domain. Individual domains were categorised in this way. A validated cutoff score of ≥10 on the SD-16 scale indicates a high level of social difficulties that requires follow-up by health or social care staff.24 This was used in our analysis as a cutoff point (socially distressed v not socially distressed). Estimated cutoff points of 5 for the Everyday Living subscale, 2 for the Money Matters subscale and 3 for the Self and Others subscale were used in this study, as per previous research.25 The five single items of the SDI-21 are scored individually.22 As the 'somewhat' option was removed from the questionnaire, FACT-Bl scores could not be calculated as per normal practice and thus cancer-specific questions from FACT-Bl were examined separately. FACT-Bl responses were grouped into those who responded 'not at all' or 'a little' and those who responded 'quite a bit' and 'very much'. Outcomes pertaining to well-being, urinary items, sexual items and body image are presented here.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report respondent characteristics, EQ-5D-5L responses, SD-16 scores, SDI-21 subscale scores and FACT-Bl responses. Outcomes were analysed in relation to age, sex, other comorbidities and type of treatment using χ2 tests. Statistical significance was set at the 1% level to minimise the chances of false-positive associations. Analyses were performed using Stata version 15 (Stata, College Station, TX).

Results

Survey population

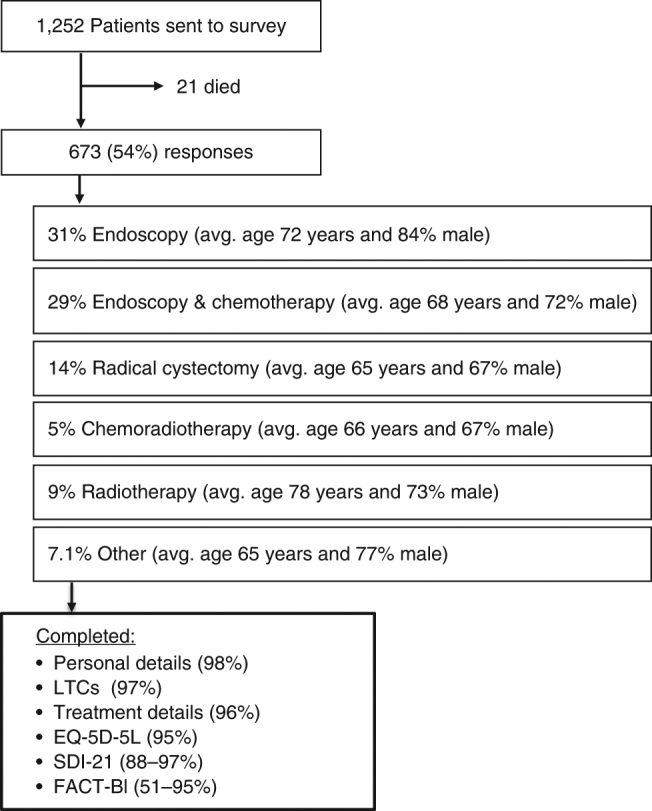

In total, 1252 BC patients were randomly identified and sent a questionnaire (Fig. 1). Of these, 21 (2%) died during the survey period, leaving 1231 eligible patients. Questionnaires were returned by 673 people (54% response rate), including 500 (74%) men and 162 (24%) women (Table 1). Most respondents were white (93%) and were in remission from BC (65%). Co-existing LTCs were common (80% reported ≥1 LTC and 29% reported ≥3). The most common treatment was endoscopy/telescopy (31%). Radical treatment was reported by 28% of respondents: of which 14% had undergone RC, 9% had received external beam radiotherapy and 5% had radiotherapy with intravenous chemotherapy. Other treatment combinations were given to <2% of respondents and therefore excluded from analysis. A stoma was present in 16% of respondents. Of the radical treatments, patients ≥85 years were more likely to be treated with radiotherapy (31%) (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Design and response rates within this survey

Table 1.

Demographics of survey respondents

| Demographic | No. of respondents | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| <55 | 53 | 7.9 |

| 55–64 | 137 | 20.4 |

| 65–74 | 247 | 36.7 |

| 75–84 | 184 | 27.3 |

| ≥85 | 35 | 5.2 |

| No response | 17 | 2.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 500 | 74.3 |

| Female | 162 | 24.1 |

| Not known | 11 | 1.6 |

| Race | ||

| White | 667 | 99.1 |

| Non white | 6 | 0.9 |

| No. of long-term conditions (LTCs) | ||

| None | 111 | 16.5 |

| 1 | 205 | 30.4 |

| 2 | 141 | 21.0 |

| ≥3 | 193 | 28.7 |

| Not reported | 23 | 3.4 |

| Disease status | ||

| Remission | 434 | 64.5 |

| Treated but cancer still present | 42 | 6.2 |

| No treatment | 2 | 0.3 |

| Recurrence | 30 | 4.5 |

| Not certain | 85 | 12.6 |

| Not reported | 80 | 11.9 |

| Treatment | ||

| Endoscopy/telescopy | 207 | 30.8 |

| Endoscopy/telescopy with chemotherapy directly into the bladder | 198 | 29.4 |

| Radical cystectomy | 92 | 13.7 |

| Radiotherapy and Intravenous chemotherapy | 36 | 5.3 |

| Radiotherapy | 63 | 9.4 |

| Other | 48 | 7.1 |

| Not reported | 29 | 4.3 |

| Stoma status | ||

| Stoma | 108 | 16.0 |

| No stoma | 437 | 65.0 |

| Not reported | 128 | 19.0 |

Respondent and non-respondent characteristics were compared, using data from NCRAS (Supplementary Table 2). Individuals older than 85 years (RR, 39%) were less likely to participate.

Data quality

Most patients answered questions relating to sex, LTCs and treatment (<5% missing responses). Of all the PROMs, FACT-Bl had the largest variety of completion rates for items and scales; with missing responses ranging from 5 to 49% (Supplementary Table 3).

Generic HRQL

Overall, 65% of respondents reported ≥1 problem on any EQ-5D-5L domain (Table 2). The percentage of respondents from treatment groups reporting ≥1 problem on any EQ-5D-5L domain ranged from 59% for endoscopy/telescopy and intravesical chemotherapy to 74% for radiotherapy. Problems with usual activities were most commonly reported (43%). Respondents treated with radiotherapy reported more problems with mobility, self-care and usual activities compared to respondents who received other treatments. Respondents with endoscopy/telescopy were more likely to report problems with mobility than respondents treated with endoscopy/telescopy and intravesical chemotherapy (47% compared to 26%, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

EQ-5D-5L number of generic health problems and domain responses by demographic

| Demographic | Problems on any EQ5D domain | Mobility | Self-care | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No problems | Problems | p-value | No problems | Problems | p-value | No problems | Problems | p-value | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Age, years | χ2 = 5.7, p = 0.226 | χ2 = 41.8, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 16.4, p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| <55 | 21 | 41.2 | 30 | 58.8 | 40 | 76.9 | 12 | 23.1 | 45 | 88.2 | 6 | 11.8 | |||

| 55–64 | 43 | 32.6 | 89 | 67.4 | 101 | 74.3 | 35 | 25.7 | 119 | 87.5 | 17 | 12.5 | |||

| 65–74 | 92 | 39.5 | 141 | 60.5 | 164 | 68.3 | 76 | 31.7 | 210 | 87.1 | 31 | 12.9 | |||

| 75–84 | 54 | 30.9 | 121 | 69.1 | 88 | 49.2 | 91 | 50.8 | 141 | 77.0 | 42 | 23.0 | |||

| ≥85 | 9 | 26.5 | 25 | 73.5 | 12 | 34.3 | 23 | 65.7 | 23 | 67.7 | 11 | 32.3 | |||

| Sex | χ2 = 0.2, p = 0.651 | χ2 = 0.3, p = 0.584 | χ2 = 0, p = 0.911 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 170 | 35.6 | 308 | 64.4 | 310 | 63.7 | 177 | 36.3 | 410 | 83.5 | 81 | 16.5 | |||

| Female | 51 | 33.6 | 101 | 66.4 | 98 | 61.2 | 62 | 38.8 | 133 | 83.1 | 27 | 16.9 | |||

| No. of long-term conditions | χ2 = 48.9, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 115.9, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 81.9, p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| None | 57 | 53.3 | 50 | 46.7 | 94 | 86.2 | 15 | 13.8 | 107 | 98.2 | 2 | 1.8 | |||

| 1 | 84 | 43.5 | 109 | 56.5 | 155 | 78.3 | 43 | 21.7 | 181 | 91.0 | 18 | 9.0 | |||

| 2 | 41 | 30.1 | 95 | 69.9 | 84 | 60.4 | 55 | 39.6 | 120 | 86.3 | 19 | 13.7 | |||

| ≥3 | 31 | 17.1 | 150 | 82.9 | 63 | 33.3 | 126 | 66.7 | 120 | 62.8 | 71 | 37.2 | |||

| Disease status | χ2 = 17.4, p = 0.01 | χ2 = 13, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 11.5, p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Remission | 170 | 40.4 | 251 | 59.6 | 288 | 66.8 | 143 | 33.2 | 371 | 85.9 | 61 | 14.1 | |||

| Treated but cancer still present | 9 | 22.5 | 31 | 77.5 | 21 | 51.2 | 20 | 48.8 | 29 | 70.7 | 12 | 29.3 | |||

| Recurrence | 8 | 26.7 | 22 | 73.3 | 20 | 66.7 | 10 | 33.3 | 25 | 83.3 | 5 | 16.7 | |||

| Not certain | 15 | 19.2 | 63 | 80.8 | 39 | 48.1 | 42 | 51.9 | 60 | 74.1 | 21 | 25.9 | |||

| Treatment | χ2 = 6.6, p = 0.156 | χ2 = 31.7, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 20.5, p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Endoscopy/telescopy | 68 | 34.5 | 129 | 65.5 | 108 | 53.5 | 94 | 46.5 | 166 | 81.0 | 39 | 19.0 | |||

| Endoscopy/telescopy with chemotherapy directly into the bladder | 80 | 41.5 | 113 | 58.5 | 145 | 74.0 | 51 | 26.0 | 177 | 89.9 | 20 | 10.1 | |||

| Radical cystectomy | 27 | 30.7 | 61 | 69.3 | 62 | 68.9 | 28 | 31.1 | 74 | 82.2 | 16 | 17.8 | |||

| Radiotherapy and Intravenous chemotherapy | 10 | 30.3 | 23 | 69.7 | 20 | 57.1 | 15 | 42.9 | 31 | 88.6 | 4 | 11.4 | |||

| Radiotherapy | 16 | 26.2 | 45 | 73.8 | 26 | 41.3 | 37 | 58.7 | 41 | 66.1 | 21 | 33.9 | |||

| Stoma status | χ2 = 1.7, p = 0.189 | χ2 = 0.2, p = 0.622 | χ2 = 0.7, p = 0.400 | ||||||||||||

| Stoma | 31 | 29.5 | 74 | 70.5 | 70 | 66.0 | 36 | 34.0 | 86 | 81.1 | 20 | 18.9 | |||

| No stoma | 152 | 36.4 | 266 | 63.6 | 271 | 63.5 | 156 | 36.5 | 365 | 84.5 | 67 | 15.5 | |||

| Demographic | Usual activities | Pain/Discomfort | Anxiety/Depression | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No problems | Problems | p-value | No problems | Problems | p-value | No problems | Problems | p-value | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Age, years | χ2 = 21, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 7.7, p = 0.103 | χ2 = 13.3, p = 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| <55 | 35 | 67.3 | 17 | 32.7 | 31 | 59.6 | 21 | 40.4 | 26 | 50.0 | 26 | 50.0 | |||

| 55–64 | 84 | 62.7 | 50 | 37.3 | 74 | 54.4 | 62 | 45.6 | 76 | 56.3 | 59 | 43.7 | |||

| 65–74 | 151 | 63.2 | 88 | 36.8 | 161 | 67.9 | 76 | 32.1 | 165 | 69.0 | 74 | 31.0 | |||

| 75–84 | 87 | 47.5 | 96 | 52.5 | 118 | 64.5 | 65 | 35.5 | 125 | 69.4 | 55 | 30.6 | |||

| ≥85 | 12 | 35.3 | 22 | 64.7 | 20 | 57.1 | 15 | 42.9 | 20 | 58.8 | 14 | 41.2 | |||

| Sex | χ2 = 3.2, p = 0.073 | χ2 = 1.9, p = 0.169 | χ2 = 0, p = 0.876 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 291 | 59.4 | 199 | 40.6 | 300 | 61.2 | 190 | 38.8 | 317 | 64.6 | 174 | 35.4 | |||

| Female | 81 | 51.3 | 77 | 48.7 | 107 | 67.3 | 52 | 32.7 | 99 | 63.9 | 56 | 36.1 | |||

| No. of long-term conditions | χ2 = 74.4, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 41.8, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 10.8, p = 0.013 | ||||||||||||

| None | 87 | 79.1 | 23 | 20.9 | 87 | 79.8 | 22 | 20.2 | 79 | 71.8 | 31 | 28.2 | |||

| 1 | 133 | 67.2 | 65 | 32.8 | 140 | 69.7 | 61 | 30.3 | 132 | 67.0 | 65 | 33.0 | |||

| 2 | 78 | 56.1 | 61 | 43.9 | 82 | 59.9 | 55 | 40.1 | 91 | 65.9 | 47 | 34.1 | |||

| ≥3 | 62 | 33.0 | 126 | 67.0 | 86 | 45.5 | 103 | 54.5 | 103 | 54.8 | 85 | 45.2 | |||

| Disease status | χ2 = 19.6, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 18, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 16.9, p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Remission | 271 | 63.3 | 157 | 36.7 | 292 | 67.9 | 138 | 32.1 | 301 | 70.2 | 128 | 29.8 | |||

| Treated but cancer still present | 20 | 48.8 | 21 | 51.2 | 21 | 52.5 | 19 | 47.5 | 19 | 47.5 | 21 | 52.5 | |||

| Recurrence | 16 | 53.3 | 14 | 46.7 | 16 | 53.3 | 14 | 46.7 | 15 | 50.0 | 15 | 50.0 | |||

| Not certain | 31 | 38.3 | 50 | 61.7 | 37 | 45.7 | 44 | 54.3 | 44 | 55.0 | 36 | 45.0 | |||

| Treatment | χ2 = 19.2, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 14.3, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 2.1, p = 0.719 | ||||||||||||

| Endoscopy/telescopy | 123 | 60.0 | 82 | 40.0 | 144 | 70.6 | 60 | 29.4 | 132 | 65.4 | 70 | 34.6 | |||

| Endoscopy/telescopy with chemotherapy directly into the bladder | 131 | 66.8 | 65 | 33.2 | 130 | 66.7 | 65 | 33.3 | 129 | 65.5 | 68 | 34.5 | |||

| Radical cystectomy | 41 | 46.1 | 48 | 53.9 | 51 | 56.0 | 40 | 44.0 | 53 | 59.6 | 36 | 40.4 | |||

| Radiotherapy and Intravenous chemotherapy | 17 | 50.0 | 17 | 50.0 | 16 | 47.1 | 18 | 52.9 | 20 | 57.1 | 15 | 42.9 | |||

| Radiotherapy | 26 | 41.9 | 36 | 58.1 | 33 | 53.2 | 29 | 46.8 | 41 | 67.2 | 20 | 32.8 | |||

| Stoma status | χ2 = 6, p = 0.014 | χ2 = 7.2, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 0.1, p = 0.807 | ||||||||||||

| Stoma | 51 | 47.7 | 56 | 52.3 | 54 | 50.5 | 53 | 49.5 | 67 | 62.6 | 40 | 37.4 | |||

| No stoma | 260 | 60.7 | 168 | 39.3 | 277 | 64.6 | 152 | 35.4 | 276 | 63.9 | 156 | 36.1 | |||

Respondents aged ≥85 years were most likely to report some problems with mobility, self-care and usual activities. Respondents <55 years old were significantly more likely to report problems with anxiety/depression, with half of this group reporting some problems, compared to between 31–44% of other age groups (p = 0.01). Those with ≥3 LTCs reported significantly more problems on all EQ-5D-5L domains bar one (anxiety/depression).

Social difficulties

SD-16

Overall, 15% of respondents were classed as socially distressed (score ≥10, Table 3). No differences were observed by sex or age group. The respondents most likely to report significantly high social distress were those treated with radiotherapy and respondents with ≥3 LTCs; with more than a quarter of respondents from these groups meeting the criteria. Respondents with a stoma were twice as likely to be socially distressed compared to respondents without a stoma.

Table 3.

Social Difficulties Inventory: SD-16 and SDI-21 subscale results by demographic

| Demographic | Social Distress | p-value | Everyday Living | p-value | Money Matters | p-value | Self and Others | p-value | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | No SD | Difficulty | No difficulty | Difficulty | No difficulty | Difficulty | No difficulty | |||||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||||

| Age, years | χ2 = 7.8, p = 0.098 | χ2 = 8.6, p = 0.071 | χ2 = 57.9, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 24.9, p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||||||

| <55 | 14 | 26.4 | 39 | 73.6 | 13 | 24.5 | 40 | 75.5 | 22 | 41.5 | 31 | 58.5 | 18 | 34.0 | 35 | 66.0 | ||||

| 55–64 | 23 | 17.3 | 110 | 82.7 | 22 | 16.3 | 113 | 83.7 | 31 | 23.3 | 102 | 76.7 | 34 | 25.0 | 102 | 75.0 | ||||

| 65–74 | 29 | 12.0 | 212 | 88.0 | 44 | 18.1 | 199 | 81.9 | 23 | 9.5 | 218 | 90.5 | 29 | 11.9 | 214 | 88.1 | ||||

| 75–84 | 23 | 13.8 | 144 | 86.2 | 43 | 24.0 | 136 | 76.0 | 11 | 6.5 | 157 | 93.5 | 21 | 11.9 | 156 | 88.1 | ||||

| ≥85 | 5 | 16.1 | 26 | 83.9 | 12 | 35.3 | 22 | 64.7 | 1 | 3.0 | 32 | 97.0 | 6 | 18.7 | 26 | 81.3 | ||||

| Sex | χ2 = 0.2, p = 0.688 | χ2 = 4.7, p = 0.031 | χ2 = 3.4, p = 0.065 | χ2 = 0.5, p = 0.484 | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 71 | 14.8 | 410 | 85.2 | 93 | 18.9 | 400 | 81.1 | 74 | 15.3 | 410 | 84.7 | 80 | 16.3 | 411 | 83.7 | ||||

| Female | 24 | 16.1 | 125 | 83.9 | 42 | 26.9 | 114 | 73.1 | 14 | 9.3 | 136 | 90.7 | 29 | 18.7 | 126 | 81.3 | ||||

| No. of long-term conditions | χ2 = 26, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 64.7, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 4.4, p = 0.221 | χ2 = 8.2, p = 0.041 | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 6 | 5.7 | 100 | 94.3 | 9 | 8.3 | 99 | 91.7 | 11 | 10.4 | 95 | 89.6 | 12 | 11.1 | 96 | 88.9 | ||||

| 1 | 23 | 11.9 | 170 | 88.1 | 25 | 12.3 | 178 | 87.7 | 25 | 12.8 | 170 | 87.2 | 34 | 17.1 | 165 | 82.9 | ||||

| 2 | 18 | 13.4 | 116 | 86.6 | 25 | 18.1 | 113 | 81.9 | 17 | 12.7 | 117 | 87.3 | 19 | 13.8 | 119 | 86.2 | ||||

| ≥3 | 48 | 26.1 | 136 | 73.9 | 77 | 41.0 | 111 | 59.0 | 34 | 18.3 | 152 | 81.7 | 43 | 22.9 | 145 | 77.1 | ||||

| Disease status | χ2 = 18.8, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 14.9, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 5.6, p = 0.134 | χ2 = 15.2, p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||||||

| Remission | 43 | 10.3 | 376 | 89.7 | 71 | 16.5 | 359 | 83.5 | 48 | 11.4 | 373 | 88.6 | 53 | 12.4 | 373 | 87.6 | ||||

| Treated but cancer still present | 10 | 24.4 | 31 | 75.6 | 12 | 29.3 | 29 | 70.7 | 4 | 9.8 | 37 | 90.2 | 7 | 17.1 | 34 | 82.9 | ||||

| Recurrence | 6 | 20.7 | 23 | 79.3 | 6 | 20.7 | 23 | 79.3 | 6 | 20.7 | 23 | 79.3 | 9 | 30.0 | 21 | 70.0 | ||||

| Not certain | 20 | 26.0 | 57 | 74.0 | 27 | 33.7 | 53 | 66.3 | 15 | 19.2 | 63 | 80.8 | 21 | 26.6 | 58 | 73.4 | ||||

| Treatment | χ2 = 22.1, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 27.7, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 7.1, p = 0.131 | χ2 = 18.1, p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||||||

| Endoscopy/telescopy | 23 | 11.6 | 176 | 88.4 | 47 | 23.1 | 156 | 76.9 | 23 | 11.6 | 176 | 88.4 | 26 | 12.9 | 176 | 87.1 | ||||

| Endoscopy/telescopy with chemotherapy directly into the bladder | 16 | 8.5 | 173 | 91.5 | 21 | 10.8 | 174 | 89.2 | 22 | 11.6 | 167 | 88.4 | 22 | 11.2 | 174 | 88.8 | ||||

| Radical cystectomy | 21 | 23.6 | 68 | 76.4 | 23 | 25.3 | 68 | 74.7 | 17 | 19.1 | 72 | 80.9 | 25 | 27.8 | 65 | 72.2 | ||||

| Radiotherapy and Intravenous chemotherapy | 7 | 20.0 | 28 | 80.0 | 7 | 20.0 | 28 | 80.0 | 7 | 20.0 | 28 | 80.0 | 7 | 20.0 | 28 | 80.0 | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 16 | 28.1 | 41 | 71.9 | 24 | 40.7 | 35 | 59.3 | 4 | 6.9 | 54 | 93.1 | 15 | 25.4 | 44 | 74.6 | ||||

| Stoma status | χ2 = 9.4, p < 0.01 | χ2 = 1.1, p = 0.293 | χ2 = 3.3, p = 0.068 | χ2 = 6, p = 0.014 | ||||||||||||||||

| Stoma | 24 | 22.6 | 82 | 77.4 | 25 | 23.1 | 83 | 76.9 | 20 | 18.9 | 86 | 81.1 | 26 | 24.1 | 82 | 75.9 | ||||

| No stoma | 48 | 11.2 | 379 | 88.8 | 81 | 18.7 | 353 | 81.3 | 52 | 12.1 | 377 | 87.9 | 62 | 14.3 | 371 | 85.7 | ||||

SDI-21 subscales

Difficulties with Everyday Living (score ≥5) were reported by 21% of respondents (Table 3). Respondents treated with radiotherapy and those who had ≥3 LTCs reported a higher level of difficulty with Everyday Living (both 41%). Comparatively fewer patients receiving other treatments reported difficulties (≤25%). When comparing patients who did not have radical treatments, significantly more respondents with endoscopy/telescopy reported difficulties with Everyday Living than respondents treated with endoscopy/telescopy and intravesical chemotherapy (23% compared to 11%, p < 0.01). Difficulties with Everyday Living did not vary by sex, age group or stoma status.

Difficulties with Money Matters (score ≥2) were reported by 14% of respondents. This difficulty was significantly more likely to be reported by respondents who were <55 years of age (42% compared to between 3 and 23% of other age groups, p < 0.01). Differences were not found for treatment type, disease status, stoma status, LTCs or sex (Table 3).

Difficulties with Self and Others (score ≥3) were reported by 17% of respondents. Reporting of significant difficulties with Self and Others was high in respondents <55 years of age, where more than a third (34%) reported difficulties (Table 3).

SDI-21 single items

The most commonly reported difficulty was with travelling or plans to take a holiday; reported by 33% of respondents. Respondents with a stoma were significantly more likely to report 'quite a bit' or 'very much' difficulty with this item than those without a stoma (29% compared to 15%, p < 0.01).

Difficulties with sexual matters were reported 'quite a bit' or 'very much' by 15% of respondents. This difficulty was significantly more likely to impact on men, 17% of whom reported 'quite a bit' or 'very much' difficulty compared to 5% of females (p < 0.01).

Cancer-specific HRQL

Physical well-being

Overall, 25% of the cohort responded that they experienced a lack of energy 'quite a bit' or 'very much', but this was higher in respondents treated with radiotherapy (43%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cancer-specific patient-reported outcomes by treatment group

| Endoscopy/telescopy | Endoscopy/telescopy with chemotherapy directly into the bladder | Radical cystectomy | Radiotherapy and Intravenous chemotherapy | Radiotherapy | p-value | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | ||||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Physical well-being | |||||||||||||||||||||

| I have a lack of energy | 150 | 76.9 | 45 | 23.1 | 155 | 83.3 | 31 | 16.7 | 68 | 78.2 | 19 | 21.8 | 25 | 73.5 | 9 | 26.5 | 34 | 56.7 | 26 | 43.3 | χ2 = 18.4, p < 0.01 |

| Because of my physical condition, I have trouble meeting the needs of my family | 162 | 90.5 | 17 | 9.5 | 173 | 96.1 | 7 | 3.9 | 77 | 88.5 | 10 | 11.5 | 29 | 87.9 | 4 | 12.1 | 39 | 78.0 | 11 | 22.0 | χ2 = 16.7, p < 0.01 |

| I have pain | 165 | 91.2 | 16 | 8.8 | 165 | 91.7 | 15 | 8.3 | 78 | 90.7 | 8 | 9.3 | 30 | 90.9 | 3 | 9.1 | 45 | 81.8 | 10 | 18.2 | χ2 = 5.1, p = 0.280 |

| Social/family well-being | |||||||||||||||||||||

| I feel close to my friends | 72 | 42.9 | 96 | 57.1 | 51 | 30.0 | 119 | 70.0 | 23 | 27.7 | 60 | 72.3 | 16 | 47.1 | 18 | 52.9 | 23 | 45.1 | 28 | 54.9 | χ2 = 12, p = 0.017 |

| My family has accepted my illness | 36 | 20.7 | 138 | 79.3 | 21 | 11.9 | 156 | 88.1 | 6 | 7.1 | 79 | 92.9 | 5 | 14.7 | 29 | 85.3 | 6 | 10.9 | 49 | 89.1 | χ2 = 10.9, p = 0.027 |

| I am satisfied with my sex life | 60 | 60.6 | 39 | 39.4 | 68 | 59.7 | 46 | 40.3 | 44 | 88.0 | 6 | 12.0 | 11 | 64.7 | 6 | 35.3 | 17 | 73.9 | 6 | 26.1 | χ2 = 14.8, p < 0.01 |

| Emotional well-being | |||||||||||||||||||||

| I feel sad | 100 | 88.5 | 13 | 11.5 | 121 | 91.0 | 12 | 9.0 | 57 | 85.1 | 10 | 14.9 | 18 | 85.7 | 3 | 14.3 | 29 | 87.9 | 4 | 12.1 | χ2 = 1.8, p = 0.781 |

| I am satisfied with how I am coping with my illness | 44 | 34.9 | 82 | 65.1 | 30 | 21.6 | 109 | 78.4 | 15 | 20.5 | 58 | 79.5 | 5 | 21.7 | 18 | 78.3 | 11 | 29.7 | 26 | 70.3 | χ2 = 8.1, p = 0.087 |

| I feel nervous | 106 | 86.2 | 17 | 13.8 | 124 | 90.5 | 13 | 9.5 | 64 | 90.1 | 7 | 9.9 | 21 | 95.5 | 1 | 4.5 | 32 | 97.0 | 1 | 3.0 | χ2 = 4.5, p = 0.343 |

| I worry about dying | 112 | 89.6 | 13 | 10.4 | 129 | 92.1 | 11 | 7.9 | 63 | 90.0 | 7 | 10.0 | 20 | 90.9 | 2 | 9.1 | 32 | 94.1 | 2 | 5.9 | χ2 = 1, p = 0.907 |

| I worry that my condition will get worse | 166 | 86.9 | 25 | 13.1 | 163 | 87.2 | 24 | 12.8 | 75 | 86.2 | 12 | 13.8 | 21 | 63.6 | 12 | 36.4 | 47 | 83.9 | 9 | 16.1 | χ2 = 13.3, p = 0.01 |

| Functional well-being | |||||||||||||||||||||

| I am able to work (include work from home) | 63 | 35.8 | 113 | 64.2 | 47 | 26.5 | 130 | 73.5 | 31 | 36.5 | 54 | 63.5 | 11 | 36.7 | 19 | 63.3 | 28 | 58.3 | 20 | 41.7 | χ2 = 17.2, p < 0.01 |

| My work (include work at home) is fulfilling | 56 | 33.9 | 109 | 66.1 | 48 | 28.6 | 120 | 71.4 | 31 | 38.3 | 50 | 61.7 | 8 | 28.6 | 20 | 71.4 | 26 | 57.8 | 19 | 42.2 | χ2 = 14.3, p < 0.01 |

| I am able to enjoy life | 46 | 24.5 | 142 | 75.5 | 32 | 16.8 | 159 | 83.2 | 22 | 24.7 | 67 | 75.3 | 2 | 6.1 | 31 | 93.9 | 17 | 28.8 | 42 | 71.2 | χ2 = 10.7, p = 0.03 |

| I am sleeping well | 66 | 34.2 | 127 | 65.8 | 52 | 28.0 | 134 | 72.0 | 29 | 32.2 | 61 | 67.8 | 12 | 35.3 | 22 | 64.7 | 18 | 31.0 | 40 | 69.0 | χ2 = 2, p = 0.739 |

| I am enjoying the things I usually do for fun | 53 | 28.5 | 133 | 71.5 | 37 | 20.0 | 148 | 80.0 | 25 | 29.1 | 61 | 70.9 | 11 | 33.3 | 22 | 66.7 | 21 | 38.9 | 33 | 61.1 | χ2 = 9.5, p = 0.049 |

| I am content with the quality of my life right now | 52 | 27.7 | 136 | 72.3 | 34 | 17.8 | 157 | 82.2 | 28 | 32.2 | 59 | 67.8 | 10 | 30.3 | 23 | 69.7 | 16 | 28.6 | 40 | 71.4 | χ2 = 9.2, p = 0.057 |

| Bladder cancer-specific items | |||||||||||||||||||||

| I have control of my bowels | 42 | 21.6 | 152 | 78.4 | 25 | 13.0 | 167 | 87.0 | 20 | 23.0 | 67 | 77.0 | 5 | 15.1 | 28 | 84.9 | 14 | 24.1 | 44 | 75.9 | χ2 = 7.6, p = 0.107 |

| I urinate more frequently than usual | 127 | 65.5 | 67 | 34.5 | 120 | 62.8 | 71 | 37.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17 | 50.0 | 17 | 50.0 | 29 | 55.8 | 23 | 44.2 | χ2 = 4, p = 0.264 |

| I have a good appetite | 43 | 21.7 | 155 | 78.3 | 25 | 13.0 | 167 | 87.0 | 19 | 22.1 | 67 | 77.9 | 4 | 11.4 | 31 | 88.6 | 14 | 23.7 | 45 | 76.3 | χ2 = 8.2, p = 0.085 |

| It burns when I urinate | 179 | 93.7 | 12 | 6.3 | 165 | 91.2 | 16 | 8.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 29 | 85.3 | 4 | 14.7 | 53 | 93.0 | 4 | 7.0 | χ2 = 3.1, p = 0.377 |

| I am interested in sex | 110 | 65.9 | 57 | 34.1 | 106 | 60.2 | 70 | 39.8 | 55 | 71.4 | 22 | 28.6 | 23 | 71.9 | 9 | 28.1 | 39 | 81.3 | 9 | 18.7 | χ2 = 9.1, p = 0.059 |

| (For men only) I am able to have and maintain an erection | 91 | 66.4 | 46 | 33.6 | 76 | 59.8 | 51 | 40.2 | 52 | 94.5 | 3 | 5.5 | 17 | 89.5 | 2 | 10.5 | 34 | 89.5 | 4 | 10.5 | NA |

Pain was reported 'quite a bit' or 'very much' by 10% of respondents and was higher in respondents with ≥3 LTCs (19%) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cancer-specific patient-reported outcomes by number of long-term conditions (LTCs)

| No LTC | 1 LTC | 2 LTCs | ≥3 LTCs | p-value | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | Not at all/somewhat | Quite a bit/very much | ||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Physical well-being | |||||||||||||||||

| I have a lack of energy | 97 | 91.5 | 9 | 8.5 | 170 | 85.9 | 28 | 14.1 | 98 | 76.0 | 31 | 24.0 | 101 | 55.5 | 81 | 44.5 | χ2 = 66, p < 0.01 |

| Because of my physical condition, I have trouble meeting the needs of my family | 104 | 98.1 | 2 | 1.9 | 170 | 91.9 | 15 | 8.1 | 116 | 94.3 | 7 | 5.7 | 132 | 80.0 | 33 | 20.0 | χ2 = 29.8, p < 0.01 |

| I have pain | 101 | 97.1 | 3 | 2.9 | 175 | 94.6 | 10 | 5.4 | 109 | 87.2 | 16 | 12.8 | 138 | 81.2 | 32 | 18.8 | χ2 = 24.9, p < 0.01 |

| Social/family well-being | |||||||||||||||||

| I feel close to my friends | 26 | 27.4 | 69 | 72.6 | 64 | 35.4 | 117 | 64.6 | 46 | 39.3 | 71 | 60.7 | 66 | 41.0 | 95 | 59.0 | χ2 = 5.3, p = 0.150 |

| My family has accepted my illness | 14 | 13.6 | 89 | 86.4 | 25 | 13.8 | 156 | 86.2 | 20 | 16.3 | 103 | 83.7 | 18 | 10.8 | 148 | 89.2 | χ2 = 1.8, p = 0.609 |

| I am satisfied with my sex life | 39 | 56.5 | 30 | 43.5 | 71 | 61.7 | 44 | 38.3 | 48 | 75.0 | 16 | 25.0 | 67 | 76.1 | 21 | 23.9 | χ2 = 10, p = 0.018 |

| Emotional well-being | |||||||||||||||||

| I feel sad | 70 | 94.6 | 4 | 5.4 | 128 | 94.1 | 8 | 5.9 | 74 | 88.1 | 10 | 11.9 | 86 | 76.1 | 27 | 23.9 | χ2 = 22.9, p < 0.01 |

| I am satisfied with how I am coping with my illness | 16 | 20.8 | 61 | 79.2 | 31 | 21.8 | 111 | 78.2 | 22 | 23.7 | 71 | 76.3 | 47 | 36.2 | 83 | 63.8 | χ2 = 9.5, p = 0.023 |

| I feel nervous | 73 | 97.3 | 2 | 2.7 | 133 | 94.3 | 8 | 5.7 | 84 | 93.3 | 6 | 6.7 | 95 | 79.2 | 25 | 20.8 | χ2 = 24.9, p < 0.01 |

| I worry about dying | 69 | 90.8 | 7 | 9.2 | 132 | 93.6 | 9 | 6.4 | 85 | 94.4 | 5 | 5.6 | 104 | 83.9 | 20 | 16.1 | χ2 = 9.6, p = 0.023 |

| I worry that my condition will get worse | 91 | 85.8 | 15 | 14.2 | 166 | 86.5 | 26 | 13.5 | 113 | 87.6 | 16 | 12.4 | 145 | 81.0 | 34 | 19.0 | χ2 = 3.3, p = 0.348 |

| Functional well-being | |||||||||||||||||

| I am able to work (include work at home) | 18 | 18.0 | 82 | 82.0 | 38 | 21.3 | 140 | 78.7 | 53 | 42.7 | 71 | 57.3 | 87 | 53.7 | 75 | 46.3 | χ2 = 55.6, p < 0.01 |

| My work (include work at home) is fulfilling | 20 | 21.5 | 73 | 78.5 | 44 | 26.0 | 125 | 74.0 | 43 | 36.8 | 74 | 63.2 | 77 | 51.3 | 73 | 48.7 | χ2 = 31.2, p < 0.01 |

| I am able to enjoy life | 16 | 15.0 | 91 | 85.0 | 29 | 14.7 | 168 | 85.3 | 25 | 19.4 | 104 | 80.6 | 60 | 33.7 | 118 | 66.3 | χ2 = 24.3, p < 0.01 |

| I am sleeping well | 23 | 21.9 | 82 | 78.1 | 52 | 26.8 | 142 | 73.2 | 44 | 33.1 | 89 | 66.9 | 75 | 41.9 | 104 | 58.1 | χ2 = 15.5, p < 0.01 |

| I am enjoying the things I usually do for fun | 16 | 15.7 | 86 | 84.3 | 31 | 16.2 | 160 | 83.8 | 34 | 27.2 | 91 | 72.8 | 79 | 45.4 | 95 | 54.6 | χ2 = 47.7, p < 0.01 |

| I am content with the quality of my life right now | 22 | 20.4 | 86 | 79.6 | 28 | 14.6 | 164 | 85.4 | 38 | 29.9 | 89 | 70.1 | 67 | 37.4 | 112 | 62.6 | χ2 = 28.2, p < 0.01 |

| Bladder cancer-specific items | |||||||||||||||||

| I have control of my bowels | 14 | 13.3 | 91 | 86.7 | 30 | 15.3 | 166 | 84.7 | 27 | 20.3 | 106 | 79.7 | 45 | 25.0 | 135 | 75.0 | χ2 = 8.3, p = 0.04 |

| I urinate more frequently than usual | 73 | 70.9 | 30 | 29.1 | 117 | 63.6 | 67 | 36.4 | 87 | 70.7 | 36 | 29.3 | 99 | 55.6 | 79 | 44.4 | χ2 = 10, p = 0.019 |

| I have a good appetite | 13 | 12.1 | 94 | 87.9 | 31 | 16.0 | 163 | 84.0 | 21 | 15.8 | 112 | 84.2 | 50 | 26.9 | 136 | 73.1 | χ2 = 13, p < 0.01 |

| It burns when I urinate | 99 | 98.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 174 | 92.6 | 14 | 7.4 | 120 | 94.5 | 7 | 5.5 | 153 | 89.0 | 19 | 11.0 | χ2 = 8.5, p = 0.036 |

| I am interested in sex | 52 | 54.2 | 44 | 45.8 | 98 | 58.0 | 71 | 42.0 | 82 | 69.5 | 36 | 30.5 | 130 | 77.8 | 37 | 22.2 | χ2 = 21.8, p < 0.01 |

| (For men only) I am able to have and maintain an erection | 42 | 61.8 | 26 | 38.2 | 87 | 66.4 | 44 | 33.6 | 75 | 78.1 | 21 | 21.9 | 107 | 82.9 | 22 | 17.1 | χ2 = 15.1, p < 0.01 |

Social/family well-being

Of the 51% who answered this item, two thirds (67%) reported dissatisfaction with their sex life ('not at all' or 'a little' satisfied with their sex life). Dissatisfaction was significantly more likely to be reported by patients who underwent RC surgery compared to those who had other treatments (Table 4). A higher percentage of females reported that they were 'quite a bit' or 'very much' satisfied with their sex life (51% compared to 31% of males, p < 0.01).

Emotional well-being

Respondents across the cohort reported a lack of satisfaction with how they were coping with their illness, as almost three-quarters of respondents reported that they were 'not at all' or 'a little' satisfied. Feeling 'quite a bit' or 'very much' nervous was reported by 10% of respondents; particularly by females (18% compared to 7% of males, p < 0.01), and those with ≥3 LTCs (Table 5).

Functional well-being

Around a third of respondents (35%) answered 'not at all' or 'a little' about their ability to work. Respondents treated with radiotherapy were less likely to be able to work compared to respondents receiving other treatments (Table 4).

Although three quarters of respondents reported that they were content with the quality of their life right now (reporting 'quite a bit' or 'very much'), respondents with ≥3 LTCs were significantly more likely to report that they were not content (Table 5).

Bladder cancer-specific items

Urinary items

Urinating more frequently than usual was common after endoscopy (reported 'quite a bit' or 'very much' in 34–37%) and radiotherapy (reported 'quite a bit' or 'very much' in 44–50%) (Table 4).

Sexual items

Disinterest in sex was reported by 66% of respondents and had a good response rate of 85%. Disinterest in sex was significantly higher in females than males, with 86% of females saying they were 'not at all' or only 'a little' interested in sex, compared to 60% of males (p < 0.01). This difference was observed (but not significant due to small numbers) when restricted to those who had a stoma, with 89% of females saying they were 'not at all' or only 'a little' interested. Ability to maintain an erection was less likely in males who had a stoma, with 96% reporting 'not at all' or 'a little' to this item, though the result was not significant due to small numbers.

Body image

Just under half of respondents said that they didn’t like their body appearance at all, or only liked it a little (48%). Respondents with a stoma were more likely to report not liking their body at all or only liking it a little (60% compared to 46% of respondents without a stoma, p = 0.01).

Discussion

Here we report HRQL in individuals between 1 and 5 years post diagnosis for BC. While modest in size compared to PROMs studies in other cancer sites, this work represents the largest UK study to date and demonstrates this methodology is feasible in this population. We have identified that reduced HRQL is common in patients following BC treatment, that there are differences according to treatment modality and patient characteristics, and that further more focused studies are warranted.

Several key findings deserve discussion. First, our results highlight the need to support people who have pre-existing health conditions and a new diagnosis of BC. Respondents with LTCs were much more likely to report poor HRQL across all EQ-5D-5L items, all domains apart from Money Matters on the SDI-21, SD-16 and on multiple items of FACT-Bl. The design and methodology used in this survey limits our ability to investigate this further and to understand whether this reflects the impact of BC on other LTCs, or the impact of other LTCs on HRQL. This is an important area for future studies to focus on.

Second, while we do not know details of each tumour (i.e., stage or grade), most patients (60%) received only endoscopic surgery. To date, most BC HRQL reports have focused upon MIBC and cystectomy outcomes. As such, our data are the first to look at HRQL in MIBC and NMIBC outcomes across a UK population. When comparing NMIBC treatments, overall, respondents receiving endoscopic surgery with intravesical chemotherapy had higher HRQL and fewer everyday living difficulties than those receiving only endoscopic surgery. This may reflect recall bias (guidelines suggest that most patients should have received intravesical chemotherapy),4 performance status (unfit patients did not receive intravesical chemotherapy), treatment differences (intravesical chemotherapy improves disease outcomes) or service design (perhaps better designed services are more guideline compliant and more likely to support patients through treatment). Support for patient selection has shown that for many domains the HRQL was superior for combined treatment rather than just endoscopic surgery.

Third, around 30% of respondents received radical therapy, including 16% who had a stoma and 9% who had received radiotherapy. The latter were most likely to report low HRQL, problems with mobility, self-care and usual activities. They were also more likely to be socially distressed (score ≥10 on SD-16), have high levels of difficulty with everyday living, report a lack of energy and an inability to work. Patients treated with radiotherapy were also more likely to report needing to urinate more frequently than usual. While these findings may reflect outcomes from radiotherapy, when compared to RC, it is more likely they reveal treatment patterns and pre-existing fitness.26 Evidence to support this is that most of these measures were better for patients who received both radiotherapy with chemotherapy (for which higher fitness is needed). Indeed outcomes from RC and radiotherapy with chemotherapy were broadly comparable to each other and to patients receiving only endoscopy/telescopy.27 Finally, overall there were some encouraging findings with social distress generally being low in respondents, as 85% were below the cutoff point, and perfect health (i.e., no problems on EQ-5D-5L) was reported by 35% of respondents.

This study has a number of key limitations. Response rates were marginally lower than for UK surveys in other cancer sites (63% for colorectal cancer)14 and 68% overall for a pilot study of individuals diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (62%), breast (68%), colorectal (64%) and prostate cancer (69%)).17 This may reflect the BC population (i.e., typically more deprived, more manual workers and lower literacy rates than other cancers).28 While respondents were willing to answer personal questions, response rates for sexual items were lower than for other domains. Details of disease stage were not available and treatment details were self-reported (and not verified from other sources) thereby reducing ability to interpret data in detail.

A major limitation was the removal by the survey developers of the 'somewhat' response option from the FACT-Bl questionnaire, which meant that composite scores could not be calculated, thus affecting the interpretation of results. Although the removal of response options from validated measures is not considered good measurement practice, we were still able to gain important information about patients who had few or no problems and patients who had severe problems with individual items. Despite this limitation, it was considered important to present the findings as there is a lack of large-scale studies looking at all BC populations. A further limitation was that, as it was a pilot study, the sample was randomly identified, rather than population-based.

The results have been presented descriptively and multivariable analysis was not undertaken. The small number of respondents in some subgroups (e.g., in some of the treatment groups) and the lack of information on important confounders (such as a measure of socioeconomic deprivation) make it difficult to obtain robust, meaningful results.

Although more detailed analysis could not be carried out in this study, it is important that future studies aim to incorporate this. In particular, quantifying the impact of treatment-related issues (e.g., urinary, bowel, sexual problems or fatigue) on HRQL and social distress is hugely important, as this will further highlight the support and care needs of this group of patients, and indicate where there are gaps in service provision.

Recent qualitative work highlighted gaps in the understanding of HRQL of BC patients (particularly patients with NMIBC).12 Important themes included post-treatment experiences in terms of family/friend support networks, dealing with incontinence, voiding and catheterising, the 'new normal' (e.g., coping with their post-surgery body), changing sexuality and living with the lifelong threat of cancer.12 Although the authors recommend longitudinal qualitative work with BC patients, based on the results of the DH study, there is also a need to undertake quantitative work to understand how HRQL changes in BC patients over time. Future work should aim to identify both high risk groups and treatment-related items with the biggest impact on HRQL. This could potentially lead to PROMs being used as part of routine practice, with risk factors for low HRQL monitored in clinic.

A further recommendation for future BC PROMs work using FACT-Bl is to include some validation work within the analysis. Although FACT-G is widely considered to be a reliable and valid tool to use with cancer patients, the bladder cancer-specific items require psychometric analysis to understand how useful these items are for use with BC populations. Alternatively, clinicians and researchers may choose other BC specific measures, such as the Bladder Cancer Index (BCI),29 or the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) NMIBC and MIBC modules.30,31

These data represent the largest PROMs study to use BC specific PROMs. The results have highlighted groups at high risk of significant adverse consequences following BC diagnosis. However, there is a need to carry out larger in-depth population-based HRQL studies of BC patients to fully understand the extent of the morbidity burden experienced by survivors of BC.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Table 1. Number of Respondents Receiving Each Treatment Type by Demographic

Supplementary Table 2. Comparison of Demographics and Clinical Characteristics Between Respondents and Nonrespondents

Supplementary Table 3. Missing Responses Data by Question

Acknowledgements

We thank all the individuals who participated in this study and the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service. The survey was administered by Picker Institute, Europe. This article is based in part on information collected and quality assured by Public Health England and NHS England. The data collection was funded by the Department of Health, England. Subsequent analysis was funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research (Award reference number: S385—The Yorkshire Cancer Research Bladder Cancer Patient-Reported Outcomes Survey).

Author contributions

Study concept and design: J.C., M.R., and A.W.G.; acquisition of data: L.H.; analysis and interpretation of data: S.J.M., A.D., P.W., L.H., J.W.C., and A.W.G.; drafting of the manuscript: S.J.M., A.D., P.W., S.E.B., J.W.C., and A.W.G.; revised the manuscript: S.J.M., A.D., P.W., S.E.B., J.W.C., and A.W.G.; approved the manuscript: all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Permission to approach patients without informed consent was given by the Health Research Authority (ref ECC 5-02(FT7)/2012). Consent to participate was implied through return of completed questionnaires.

Availability of data and material

The aggregated results of data analysis, STATA files and output for data extraction are available from the authors on request. Individual patient-level data used to generate results are not freely available, but may be applied for through the PHE Office for Data Release (ODR).

Footnotes

Joint senior authors: James W Catto, Adam W Glaser.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41416-018-0084-z.

References

- 1.Antoni S, et al. Bladder cancer incidence and mortality: a global overview and recent trends. Eur. Urol. 2017;71:96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svatek RS, et al. The economics of bladder cancer: costs and considerations of caring for this disease. Eur. Urol. 2014;66:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linton KD, et al. Disease specific mortality in patients with low risk bladder cancer and the impact of cystoscopic surveillance. J. Urol. 2013;189:828–833. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babjuk M, et al. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2016. Eur. Urol. 2017;71:447–461. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rhijn BWG, et al. Recurrence and progression of disease in non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer: from epidemiology to treatment strategy. Eur. Urol. 2009;56:430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansson A, Davidsson T, Hunt S, Mansson W. The quality of life in men after radical cystectomy with a continent cutaneous diversion or orthotopic bladder substitution: is there a difference? Bju. Int. 2002;90:386–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caffo O, Fellin G, Graffer U, Luciani L. Assessment of quality of life after cystectomy or conservative therapy for patients with infiltrating bladder carcinoma—A survey by a self-administered questionnaire. Cancer. 1996;78:1089–1097. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960901)78:5<1089::AID-CNCR20>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allareddy V, Kennedy J, West MM, Konety BR. Quality of life in long-term survivors of bladder cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:2355–2362. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuda T, Aptel I, Exbrayat C, Grosclaude P. Determinants of quality of life of bladder cancer survivors five years after treatment in France. Int. J. Urol. 2003;10:423–429. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedgepeth RC, Gilbert SM, He C, Lee CT, Wood DP., Jr. Body image and bladder cancer specific quality of life in patients with ileal conduit and neobladder urinary diversions. Urology. 2010;76:671–675. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imbimbo C, et al. Quality of life assessment with orthotopic ileal neobladder reconstruction after radical cystectomy: results from a Prospective Italian Multicenter Observational Study. Urology. 2015;86:974–979. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edmondson AJ, Birtwistle JC, Catto JWF, Twiddy M. The patients’ experience of a bladder cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:453–461. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0603-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer S, et al. Quality of life in patients with muscle invasive and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Support. Care Cancer. 2013;21:1383–1393. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downing A, et al. Health-related quality of life after colorectal cancer in England: A Patient-Reported Outcomes Study of Individuals 12 to 36 Months After Diagnosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:616–624. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.6539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downing A, et al. Life after prostate cancer diagnosis: protocol for a UK-wide patient-reported outcomes study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013555. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung C, et al. Impact of bladder cancer on health related quality of life in 1476 older Americans: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Urol. 2014;192:690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.03.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser Adam W, Fraser Lorna K, Corner Jessica, Feltbower Richard, Morris Eva J A, Hartwell Greg, Richards Mike. Patient-reported outcomes of cancer survivors in England 1–5 years after diagnosis: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):e002317. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partington J., et al. Living with and beyond bladder cancer: A descriptive summary of responses to a pilot of Patient Reported Outcome Measures for bladder cancer. Public Health England/NHS England; 2015. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/proms-bladder-cancer.pdf

- 19.Herdman M, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual. Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams A. Euroqol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality-of-life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright EP, et al. Development and evaluation of an instrument to assess social difficulties in routine oncology practice. Qual. life Res. 2005;14:373–386. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-5332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright P, Smith A, Roberts K, Selby P, Velikova G. Screening for social difficulties in cancer patients: clinical utility of the Social Difficulties Inventory. Br. J. Cancer. 2007;97:1063–1070. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella DF, et al. The functional assessment of cancer-therapy scale—development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright P, Marshall L, Smith A, Velikova G, Selby P. Measurement and interpretation of social distress using the social difficulties inventory (SDI) Eur. J. Cancer. 2008;44:1529–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright P, et al. Identifying social distress: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Social Outcomes 12 to 36 Months After Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:3423–3430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.6129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seisen T, et al. Comparative effectiveness of trimodal therapy versus radical cystectomy for localized muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur. Urol. 2017;72:483–487. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali AS, Hayes MC, Birch B, Dudderidge T, Somani BK. Health related quality of life (HRQoL) after cystectomy: comparison between orthotopic neobladder and ileal conduit diversion. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015;41:295–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noon Aidan P., Martinsen Jan Ivar, Catto James W.F., Pukkala Eero. Occupation and Bladder Cancer Phenotype: Identification of Workplace Patterns That Increase the Risk of Advanced Disease Beyond Overall Incidence. European Urology Focus. 2018;4(5):725–730. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert SM, et al. Development and validation of the bladder cancer index: a comprehensive, disease specific measure of health related quality of life in patients with localized bladder cancer. J. Urol. 2010;183:1764–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blazeby JM, et al. Validation and reliability testing of the EORTC QLQ-NMIBC24 questionnaire module to assess patient-reported outcomes in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. 2014;66:1148–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mak KS, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016;96:1028–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Number of Respondents Receiving Each Treatment Type by Demographic

Supplementary Table 2. Comparison of Demographics and Clinical Characteristics Between Respondents and Nonrespondents

Supplementary Table 3. Missing Responses Data by Question