Abstract

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are great challenges in public health, where cardiovascular diseases (CVD) accounted for the large part of mortality that caused by NCDs. Multimorbidity is very common in NCDs especially in CVD, thus multimorbidity could make NCDs worse and bring heavy economic burden. This study aimed to explore the multimorbidity among adults, especially the important role of CVD that played in the entire multimorbidity networks. A total of 21435 participants aged 18–79 years old were recruited in Jilin province in 2012. Weighted networks were adopted to present the complex relationships of multimorbidity, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to evaluate the burden of multimorbidity. The prevalence of CVD was 14.97%, where the prevalence in females was higher than that in males (P < 0.001), and the prevalences of CVD increased with age (from 2.22% to 38.38%). The prevalence of multimorbidity with CVD was 96.17%, and CVD could worsen the burden of multimorbidity. Multimorbidity and multimorbidity with CVD were more marked in females than those in males. And the prevalence of multimorbidity was the highest in the middle-age, while the prevalence of multimorbidity with CVD was the highest in the old population.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are believed as leading causes of death in the world, and regarded as major threats to human health and sustainable development1–3. Of these, 17.60 million people died from cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in 20164. In China, there were 230 million patients with CVD in 20105, and the burden of CVD was also predicted to be a high level. Moreover, multimorbidity is very common in CVD, and it is reported that more than 50% CVD patients suffer from at least one additional disease6,7. Multimorbidity not only affects the quality of life among CVD patients, but also can bring heavy economic burden to individuals, families and the society8.

Many occurrences of multimorbidity with CVD had been recognized and investigated in previous studies, and hypertension was one of the most widely studied occurrences of multimorbidity with CVD9–11. World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out that approximately 13% of CVD deaths were accounted for hypertension12. Diabetes13,14, obesity15, and dyslipidemia16,17 were also recognized as the common occurrences of multimorbidity with CVD. Besides, some other diseases such as chronic respiratory disease18, liver disease19 and depression20 had been studied as potential occurrences of multimorbidity with CVD as well.

Moreover, some studies also showed that the pattern of multimorbidity of CVD was different among groups stratified by sex and age6,21–23. A study documented that the prevalence of anemia was the highest in female patients with heart failure, whereas the prevalence of dyslipidemia was the highest in male patients with heart failure6. Another study found that there were gender differences in the pattern of multimorbidity with CVD, and male patients were more likely to have multimorbidity22.

However, previous studies concerned only on one single occurrence of multimorbidity, rather than the overall occurrences of multimorbidity that covered information of multiple NCDs. In this study, we explored and presented the multimorbidity among adults in Jilin province, northeast China (Latitude 40°~46°, Longitude 121°~131°) in 2012, especially the important role of CVD that played in the entire multimorbidity networks. Weighted networks were adopted to demonstrate the complex relationships of co-occurrence of NCDs. The prevalences of multimorbidity and multimorbidity with CVD were more marked in females than those in males, and the prevalences were extremely high in the old population. We found that multimorbidity was extremely common among CVD patients, and CVD would also worsen the burden of multimorbidity.

Results

Sex-specific and age-specific distributions of top 20 NCDs of participants

Table 1 presents the top 20 NCDs with the highest prevalences, and the ranks of these diseases were a little different by sex and age. The prevalences of majority diseases were different by sex and age as well (P < 0.05). The prevalence of CVD was 14.49% (ranked the third), where in females it was higher than that in males, and the prevalences of CVD increased with age (from 2.22% to 38.38%).

Table 1.

Sex-specific and age-specific distributions of top 20 NCDs of participants (n = 21435) in Northeast China [n (%)].

| Rank | Disease | Total | Gender | χ 2 | P-value | Agea | χ 2 | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 10337) | Female (n = 11098) | Young (n = 6657) | Middle-age (n = 12980) | Old (n = 1798) | |||||||

| 1 | Hyperlipidemia | 10951(51.09) | 5379(52.04) | 5572(50.21) | 7.166 | 0.007 | 2288(34.37) | 7504(57.81) | 1159(64.46) | 1108.124 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Hypertension | 7511(35.04) | 3893(37.66) | 3618(32.60) | 60.209 | <0.001 | 892(13.40) | 5470(42.14) | 1149(63.90) | 2315.335 | <0.001 |

| 3 | CVD | 3209(14.97) | 1213(11.73) | 1996(17.99) | 164.269 | <0.001 | 148(2.22) | 2371(18.27) | 690(38.38) | 1734.311 | <0.001 |

| 4 | Obesity | 3105(14.49) | 1529(14.79) | 1576(14.20) | 1.508 | 0.219 | 846(12.71) | 2034(15.67) | 225(12.51) | 37.322 | <0.001 |

| 5 | Disc disease | 2893(13.50) | 1117(10.81) | 1776(16.00) | 123.814 | <0.001 | 456(6.85) | 2175(16.76) | 262(14.57) | 371.832 | <0.001 |

| 6 | Diabetes | 1956(9.13) | 972(9.40) | 984(8.87) | 1.859 | 0.173 | 143(2.15) | 1488(11.46) | 325(18.08) | 650.085 | <0.001 |

| 7 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 1942(9.06) | 638(6.17) | 1304(11.75) | 202.102 | <0.001 | 192(2.88) | 1453(11.19) | 297(16.52) | 501.314 | <0.001 |

| 8 | Gastroenteritis | 1923(8.97) | 845(8.17) | 1078(9.71) | 15.521 | <0.001 | 570(8.56) | 1218(9.38) | 135(7.51) | 8.778 | 0.012 |

| 9 | Cholecystitis | 1585(7.39) | 354(3.42) | 1231(11.09) | 459.494 | <0.001 | 229(3.44) | 1217(9.38) | 139(7.73) | 226.747 | <0.001 |

| 10 | Gynecological inflammation | 1252(5.84) | 0 | 1252(11.28) | — | — | 460(14.92) | 770(10.89) | 22(2.38) | 117.454 | <0.001b |

| 11 | Gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer | 819(3.82) | 427(4.13) | 392(3.53) | 5.219 | 0.022 | 164(2.46) | 570(4.39) | 85(4.73) | 48.890 | <0.001 |

| 12 | Chronic bronchitis | 767(3.58) | 331(3.20) | 436(3.93) | 8.188 | 0.004 | 82(1.23) | 544(4.19) | 141(7.84) | 215.102 | <0.001 |

| 13 | Prostate hyperplasia or inflammation | 648(3.02) | 648(6.27) | 0 | — | — | 43(1.20) | 464(7.85) | 141(16.53) | 334.018 | <0.001c |

| 14 | Anemia | 594(2.77) | 72(0.70) | 522(4.70) | 318.934 | <0.001 | 247(3.71) | 309(2.38) | 38(2.11) | 32.030 | <0.001 |

| 15 | Fatty liver | 510(2.38) | 267(2.58) | 243(2.19) | 3.566 | 0.059 | 100(1.50) | 377(2.90) | 33(1.84) | 39.753 | <0.001 |

| 16 | Calculus in urinary system | 481(2.24) | 271(2.62) | 210(1.89) | 12.981 | <0.001 | 90(1.35) | 348(2.68) | 43(2.39) | 35.629 | <0.001 |

| 17 | Rheumatic | 442(2.06) | 108(1.04) | 334(3.01) | 102.302 | <0.001 | 63(0.95) | 320(2.47) | 59(3.28) | 64.721 | <0.001 |

| 18 | Nasopharyngitis | 439(2.05) | 233(2.25) | 206(1.86) | 4.223 | 0.040 | 155(2.33) | 257(1.98) | 27(1.50) | 5.583 | 0.061 |

| 19 | Cataract | 402(1.88) | 113(1.09) | 289(2.60) | 66.392 | <0.001 | 4(0.06) | 219(1.69) | 179(9.96) | 759.591 | <0.001 |

| 20 | Gallstone | 384(1.79) | 125(1.21) | 259(2.33) | 38.466 | <0.001 | 43(0.65) | 284(2.19) | 57(3.17) | 80.677 | <0.001 |

aThe people with age less than 40 (age ≤ 40) were viewed as young, and people with 41 ≤ age ≤ 65 and age ≥ 66 were middle-age and old, respectively.

bThe χ2 and the p-value were calculated among women only; cthe χ2 and the p value were calculated among men only.

Sex-specific and age-specific top 5 patterns of multimorbidity

Table 2 shows the sex-specific and age-specific prevalences of top 5 patterns of multimorbidity, with the pair hyperlipidemia & hypertension as the highest one. Generally, the prevalences of CVD & hyperlipidemia and CVD & hypertension were also very high, especially in the old population.

Table 2.

Sex-specific and age-specific top 5 patterns of multimorbidity [n (%)].

| Group | Top 1 | Top 2 | Top 3 | Top 4 | Top 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | — | Hyperlipidemia & Hypertension | Obesity & Hyperlipidemia | CVD & Hyperlipidemia | CVD & Hypertension | Obesity & Hypertension |

| 5015(23.40) | 2183(10.18) | 2065(9.63) | 1913(8.92) | 1759(8.21) | ||

| Sex | Male | Hyperlipidemia & Hypertension | Obesity & Hyperlipidemia | Obesity & Hypertension | CVD & Hypertension | CVD & Hyperlipidemia |

| 2564(24.80) | 1101(10.65) | 870(8.42) | 782(7.57) | 751(7.27) | ||

| Female | Hyperlipidemia & Hypertension | CVD & Hyperlipidemia | CVD & Hypertension | Obesity & Hyperlipidemia | Hyperlipidemia & Disc disease | |

| 2451(22.09) | 1314(11.84) | 1131(10.19) | 1082(9.75) | 1051(9.47) | ||

| Agea | Young | Hyperlipidemia & Hypertension | Obesity & Hyperlipidemia | Obesity & Hypertension | Hyperlipidemia & Gastroenteritis | Hyperlipidemia & Disc disease |

| 528(7.93) | 519(7.80) | 282(4.24) | 211(3.17) | 196(2.94) | ||

| Middle-age | Hyperlipidemia & Hypertension | CVD & Hyperlipidemia | Obesity & Hyperlipidemia | CVD & Hypertension | Hyperlipidemia & Disc disease | |

| 3708(28.57) | 1543(11.89) | 1488(11.46) | 1380(10.63) | 1321(10.18) | ||

| Old | Hyperlipidemia & Hypertension | CVD & Hypertension | CVD & Hyperlipidemia | Diabetes & Hypertension | Diabetes & Hyperlipidemia | |

| 779(45.58) | 490(28.67) | 472(27.62) | 236(13.81) | 232(13.58) | ||

aThe people with age less than 40 (age ≤ 40) were viewed as young, and people with 41 ≤ age ≤ 65 and age ≥ 66 were middle-age and old, respectively.

Sex-specific and age-specific top 5 patterns of multimorbidity with CVD

Multimorbidity was extremely common among CVD patients, where there were 96.17% (3086/3209) CVD patients suffered from at least one other NCDs. Further, the prevalence of multimorbidity with CVD in females (97.29%) was more marked than that in males (94.31%), and it was the worst among old (97.54%) CVD patients (P < 0.001, 85.81% for the young and 96.42% for the middle-age). The top 5 patterns of sex-specific and age-specific multimorbidity with CVD were shown in Table 3. In general, the ranks for multimorbidity with CVD were similar, where hyperlipidemia and hypertension were the most frequent occurrences of multimorbidity among CVD patients, thus the “CVD-Hyperlipidemia-Hypertension” (CVD-H-H) triangle was inclined to play an important role in the multimorbidity networks.

Table 3.

Sex-specific and age-specific top 5 patterns of multimorbidity among CVD patients [n (%)].

| Group | Top 1 | Top 2 | Top 3 | Top 4 | Top 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | — | Hyperlipidemia | Hypertension | Disc disease | Rheumatoid arthritis | Obesity |

| 2065(9.63) | 1913(8.92) | 806(3.76) | 639(2.98) | 611(2.85) | ||

| Sex | Male | Hypertension | Hyperlipidemia | Disc disease | Diabetes | Obesity |

| 782(7.57) | 751(7.27) | 235(2.27) | 215(2.08) | 214(2.07) | ||

| Female | Hyperlipidemia | Hypertension | Disc disease | Rheumatoid arthritis | Obesity | |

| 1314(11.84) | 1131(10.19) | 571(5.15) | 479(4.32) | 397(3.58) | ||

| Agea | Young | Hyperlipidemia | Hypertension | Disc disease | Gastroenteritis | Gynecological inflammation |

| 50(0.75) | 43(0.62) | 41(0.65) | 29(0.44) | 29(0.44) | ||

| Middle-age | Hyperlipidemia | Hypertension | Disc disease | Obesity | Rheumatoid arthritis | |

| 1543(11.89) | 1380(10.63) | 627(4.83) | 479(3.69) | 468(3.61) | ||

| Old | Hypertension | Hyperlipidemia | Rheumatoid arthritis | Disc disease | Diabetes | |

| 490(27.25) | 472(26.25) | 157(8.73) | 138(7.68) | 133(7.40) | ||

aThe people with age less than 40 (age ≤ 40) were viewed as young, and people with 41 ≤ age ≤ 65 and age ≥ 66 were middle-age and old, respectively.

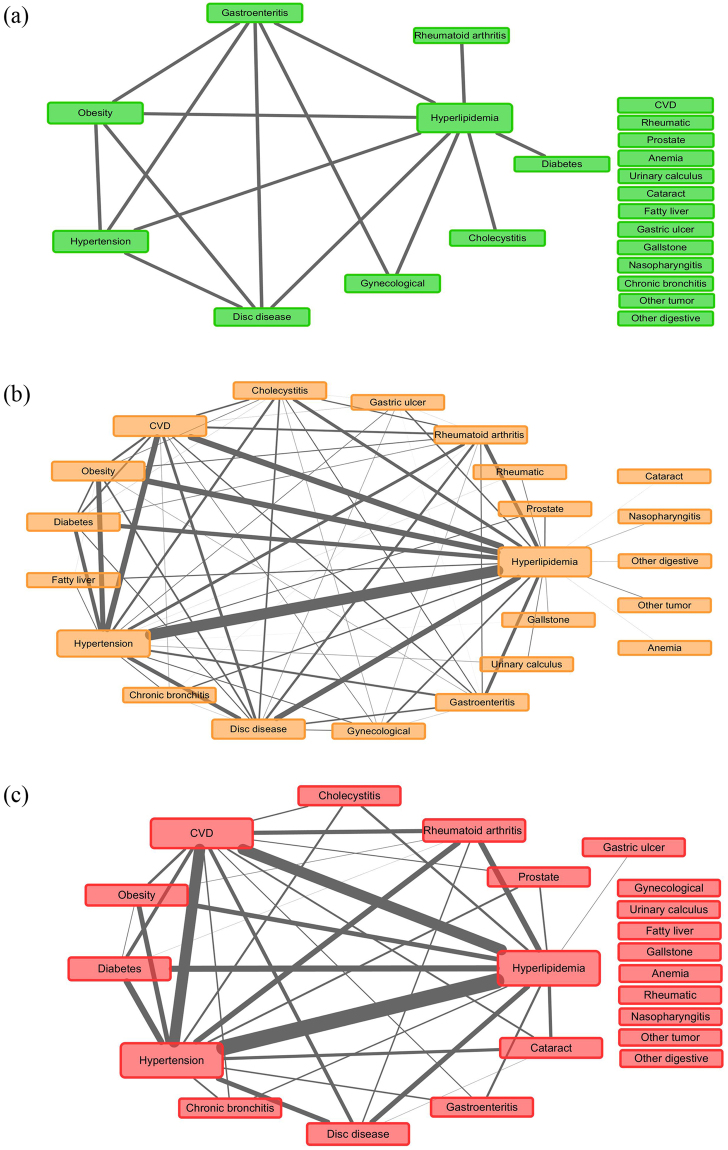

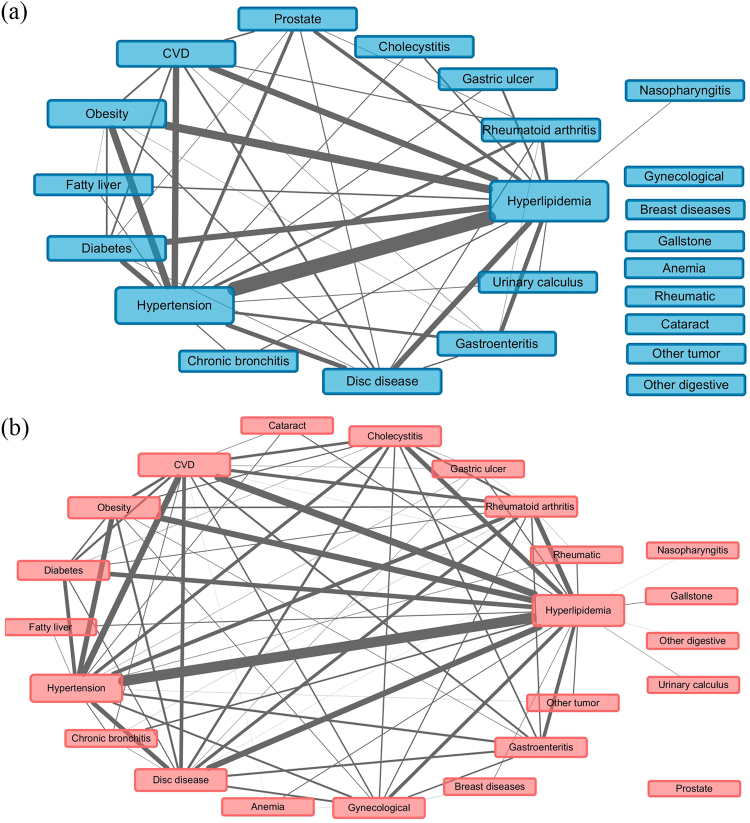

Evaluation of multimorbidity and multimorbidity networks

Figures 1–3 showed the networks of the multimorbidity in the whole population, as well as the sex-specific and age-specific populations, and Table 4 list the indices which could measure the features of the networks. The network density and the average degree of females were larger than those of males, thus the network of females was much denser than that of males, i.e., the NCDs in females tended to co-occur more frequently than those in males. Meanwhile, the network density (as well as the average degree) reached the largest in the middle-age, and smallest in the young. In Table 4, each average degree of the CVD-H-H triangle was extremely higher than that of its network, where the average degree of the triangle in old population was 6.9 (22.67/3.27) times of its own network (Fig. 3(c)), which was the largest. Meanwhile, the proportion of CVD that contributed to the CVD-H-H triangle in old population was also the largest (11/(11 + 12 + 11) = 32.35%). The average degree of the CVD-H-H triangle in females was more marked than that in males, but compared with the corresponding female/male network, the CVD-H-H triangle in males was more important, which was 6.6 (24.67/3.74) times of its network (Fig. 2(b)). However, the proportion of CVD that contributed to the CVD-H-H triangle in males (8/(8 + 14 + 15) = 21.62%) was smaller than that in females (14/(14 + 21 + 13) = 29.17%).

Figure 1.

Multimorbidity network for the whole population, where “Prostate” represented “Prostate hyperplasia or inflammation”, “Gynecological” represented gynecological inflammation, “Gastric ulcer” represented gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer; “other tumor” represented tumors except 9 cancer like liver cancer, lung cancer, etc.

Figure 3.

Multimorbidity networks by age group, where (a) for young (age ≤ 40), (b) for middle-age (41 ≤ age ≤ 65), and (c) for old (age ≥ 66), “Prostate” represented “Prostate hyperplasia or inflammation”, “Gynecological” represented gynecological inflammation, “Gastric ulcer” represented gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer; “other tumor” represented tumors except 9 cancer like liver cancer, lung cancer, etc., and “other digestive” represented other diseases of digestive system except 7 ones like fatty liver, cirrhosis, etc.

Table 4.

Evaluation of multimorbidity and multimorbidity networks.

| Group | Network density | Average degree | Average degree of CVD-H-Hb | CCI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD | non-CVD | Z | P-value | |||||

| Total | — | 0.305 | 5.80 | 29.33 (10, 19, 15) | 3.80 ± 1.62 | 1.19 ± 1.34 | 72.26 | <0.001 |

| Sex | Male | 0.170 | 3.74 | 24.67 (8, 14, 15) | 3.71 ± 1.54 | 1.20 ± 1.31 | 45.41 | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.296 | 6.52 | 32.00 (14, 21, 13) | 3.86 ± 1.66 | 1.18 ± 1.38 | 55.82 | <0.001 | |

| Agea | Young | 0.065 | 1.36 | 8.00 (0, 8, 4) | 1.72 ± 1.03 | 0.29 ± 0.56 | 21.99 | <0.001 |

| Middle-age | 0.303 | 6.36 | 32.00 (11, 21, 16) | 3.52 ± 1.44 | 1.48 ± 1.24 | 55.15 | <0.001 | |

| Old | 0.156 | 3.27 | 22.67 (11, 12, 11) | 5.22 ± 1.26 | 3.74 ± 1.08 | 23.09 | <0.001 | |

aThe people with age less than 40 (age ≤ 40) were viewed as young, and people with 41 ≤ age ≤ 65 and age ≥ 66were middle-age and old, respectively.

bCVD-H-H refers to the “CVD-Hyperlipidemia-Hypertension” triangle in the network, and the values in the brackets are degrees of CVD, hyperlipidemia and hypertension.

Figure 2.

Multimorbidity networks by sex, where (a) for males and (b) for females, “Prostate” represented “Prostate hyperplasia or inflammation”, “Gynecological” represented gynecological inflammation, “Gastric ulcer” represented gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer; “other tumor” represented tumors except 9 cancer like liver cancer, lung cancer, etc., and “other digestive” represented other diseases of digestive system except 7 ones like fatty liver, cirrhosis, etc.

Finally, the severity of the multimorbidity using Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was also shown in Table 4. It was no surprising that the CCI in the population with CVD was extremely larger than that without CVD in all groups (P < 0.001), which indicated that CVD would bring extra burden to multimorbidity. Further, the CCIs in males were smaller than those in females (P = 0.013 for CVD and P = 0.002 for non-CVD), and CCIs were the highest among the elderly, and the lowest among the young (all P < 0.001).

Discussion

NCDs are believed to bring great challenges to and have important impacts on public health nowadays, which accounted for 63% of deaths worldwide in 2008, and CVD is one of the most important main causes of deaths24. Meanwhile, multimorbidity was extremely common among the CVD patients7,25. In this study, we investigated the multimorbidity of 57 kinds of NCDs based on 21435 adults in Jilin province in 2012, especially the multimorbidity with CVD. Hyperlipidemia, hypertension and CVD were top 3 NCDs with the highest prevalences in Jilin province. Multimorbidity and the multimorbidity with CVD were more marked in females than those in males. The prevalence of multimorbidity was the highest in middle-age, whereas the prevalence of multimorbidity with CVD was the highest in the old population. 96.17% CVD patients suffered from multimorbidity, where the prevalence of multimorbidity increased with age, and CVD would worsen the burden of multimorbidity.

Hyperlipidemia, hypertension and CVD were top 3 NCDs with the highest prevalences in Jilin province, regardless of sex and age. The prevalence of CVD was 14.97%, which was lower than other studies in literature5,26, due to that hypertension was not included in CVD in this study. Although CVD ranked the third, the analysis of CCI suggested that CVD would bring extra burden to multimorbidity and increase the 10-year mortality27, thus the lethality and the burden of CVD with multimorbidity was much higher. Besides, among the top 5 patterns of multimorbidity there were 2 patterns of multimorbidity with CVD, which suggested that multimorbidity with CVD were very common. And 96.17% CVD patients suffered from multimorbidity, which was higher than other studies22,23, one possible reason might be that hyperlipidemia was investigated in our study.

Further, the CVD-H-H triangle in males was more marked than that in females, relative to their own network, but CVD in males contributed less proportions to the triangle than that in females. It was suggested that hyperlipidemia and hypertension in males played more important roles in multimorbidity, while CVD and its multimorbidity were more common in females, and would bring more risk to females28,29. Therefore, different strategies should be developed to prevent NCDs and their multimorbidity in males and females separately.

Finally, the prevalences of majority multimorbidity were the highest in the eldly, and the lowest in the young, which were consistent with other studies30,31. The possible reason might be that body immunity and function declined with age, so that the old people were more vulnerable to NCDs and their multimorbidity32. Although the middle-age had a denser multimorbidity network, the CVD-H-H triangle in the old population played a more important role, relative to their own network, where there CVD occupied large percentage compared with that of the young and middle-age. Thus it suggested different key prevention towards different age groups: multimorbidity with CVD were tended to cluster in the old population, while nutritional or metabolic diseases were common for young people33.

Some limitations should be noted here. Firstly, the participants in the study were selected in Jilin province, which could not represent the (CVD) multimorbidity in other places. Secondly, the disease situations were mainly based on self-report, which might cause bias. Thirdly, only cerebrovascular disorders, angina pectoris, coronary disease and myocardial infarction were involved in CVD, which might underestimate the prevalence of CVD and its multimorbidity. Finally, only sex and age were investigated in the study, but other factors that might have effects on the multimorbidity were worthy of further study.

Methods

Study population

Data were derived from a cross-sectional survey in Jilin Province of China in 2012, and the multistage stratified cluster sampling method was used to select the study samples. A total of 23050 participants who had lived in Jilin Province for more than 6 months and were 18–79 years old were selected (see more details in Part 1 of the Supplementary Material). For the purpose of the present analyses, some subjects were excluded due to missing values (1615 subjects). Finally, a total of 21435 subjects were included in the present analyses.

Ethics Statement

The ethics committee of the School of Public Health, Jilin University (Reference Number: 2012-R-011) and the Bureau of Public Health of Jilin Province (Reference Number: 2012–10) approved the study. All research methods followed the guidelines of investigation and written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants before data collection.

Data collection and measurement

The data of this study included demographics, anthropometric measurements (e.g., height, weight, blood pressure) and NCDs situations (57 NCDs, including liver cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, cervical cancer, prostate cancer, thyroid carcinoma, leukemia and other tumor (except the above 9 ones); anemia, rheumatic and other hematologic and immune related diseases (except the above 2); obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, thyrotoxicosis, osteoporosis, gout and other endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (except the above 6 ones); schizophrenia, depression and other mental & behavioral disorders (except the above 2); cognition disorders, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease and other neurological diseases (except the above 3 ones); cataract, glaucoma and other eye diseases (except the above 2); hypertension, CVD (including cerebrovascular disorders, angina pectoris, coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction), corpulmonale, varicose veins of lower extremity and other diseases of circulatory system (except the above 4 ones); chronic obstructive pulmonary emphysema, asthma, nasopharyngitis, chronic bronchitis, and other respiratory diseases (except the above 4 ones); gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer, fatty liver, cirrhosis, cholecystitis, gallstone, gastroenteritis, hernia of abdominal cavity, and other diseases of digestive system (except the above 7 ones); rheumatoid arthritis, disc disease, and other musculoskeletal and connective tissue diseases(except the above 2); nephritis, gynecological inflammation, breast diseases, urinary calculus, prostate hyperplasia or inflammation and other diseases of genitourinary system (except the above 5 ones)).

After 12 or more hours of overnight fasting, finger-tip blood samples were taken from the subjects, and the plasma glucose (FPG) level was analyzed; the 2-hour FPG level was also tested. These tests were conducted by a Bayer Bai Ankang fingertip blood glucose monitor machine. The serum lipids, including total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), were measured before breakfast, using enzymatic methods in a central laboratory with standardized testing. Weight and height were performed after removing shoes and heavy outer clothing. Weights were measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a calibrated scale with the subjects standing in an upright position, and heights were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a standard anthropometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Blood pressure was measured using mercury sphygmomanometer in the sitting position after a 5-min rest period by trained professionals. Two readings each of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were recorded, and the average of each measurement was used for data analysis. If the first two measurements differed by more than 5 mmHg, additional readings were taken34–36.

Assessment criteria of disease

Hypertension was referred to those with SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg, and/or DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg, and/or normotensives treated with antihypertensive medications, and/or a self-reported history of hypertension37. Hyperlipidemia was defined as TC ≥ 5.18 mmol/L, and/or LDL-C ≥ 3.37 mmol/L, and/or HDL-C < 1.04 mmol/L, and/or TG ≥ 1.70 mmol/L, and/or normolipidemic subjects treated with antihyperlipidemia medications, and/or with history of hyperlipidemia diseases38. Obesity was defined as the BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 39. Diabetes was defined as FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l (126 mg/dl) and/or a self-reported history of diabetes. CVD was defined as a participant carried at least one of the following disease: cerebrovascular disorders, angina pectoris, coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction. Other NCDs were judged only by self-reported history of diseases which diagnosed in hospitals on county level and above.

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD) and compared using the t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The categorical variables were expressed as counts or percentages and compared using the Rao-Scott-χ2 test. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.4.1 (University of Auckland, Oakland, New Zealand). Statistical significance was set at a P value < 0.05.

In this study, weighted networks were applied to study the relationships among multimorbidity. The nodes of the network represented the diseases, and the height of each node was proportional to the prevalence of each disease. The edge in the network represented the co-occurrence of a multimorbidity pair, and the weight of the edge was proportional to the prevalence of each multimorbidity pair. When a participant carried more than 2 diseases, the count of every multimorbidity pair would have an increment of 1 (e.g., when a participant carried CVD, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, then the multimorbidity pair CVD & hypertension, hypertension & hyperlipidemia and hyperlipidemia & CVD would have an increment of 1). The prevalence of disease or multimorbidity pair were calculated as the total counts of participants which carried the disease or multimorbidity pair divided by the corresponding sample size. The relationships of the multimorbidity with prevalence higher than 1% were list in the networks in our study.

Degree was adopted to measure the centrality of a disease (e.g. CVD), where degree was the number of nodes that a focal node was connected to, which measured the involvement of the node in the network. Network density and average degree were used to evaluate the sparsity of a network. The network density of an undirected graph with N nodes and M edges was defined as 2 M/N(N − 1), which described the portion of the potential connections (N(N − 1)/2) in a network that were actual connections (M). The average degree was defined as the average of degrees of all nodes. The larger the network density (or average degree), the denser the network40,41. CCI was used to measure the burden of multimorbidity or comorbidity, which had been validated in many clinical settings to describe the condition of comorbidity and multimorbidity42,43. The larger the CCI, the worse the condition of multimorbidity (the larger 10-year mortality).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province, China (grant number: 20180101129JC), the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province, China (grant number: 20170520049JH), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 11301213 and 11571068), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number: 2016YFC1303800) and the Scientific Research Foundation of the Health Bureau of Jilin Province, China (grant number: 2011Z116).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Lina Jin, Yan Yao, Yaqin Yu. Data curation and analysis: Lina Jin, Xin Guo, Yan Yao. Performed the weighted networks: Lina Jin, Binghui Liu, Jiangzhou Wang, Jiagen Li. Wrote the original draft of the manuscript: Xin Guo, Jing Dou, Mengzi Sun, Chong Sun. Contributed to reviewing and editing of the manuscript: Lina Jin, Yan Yao, Xin Guo, Jing Dou. Agree with the manuscript’s results and conclusions: Lina Jin, Xin Guo, Jing Dou, Jiagen Li, Mengzi Sun, Chong Sun, Yan Yao. All authors have read, and confirm that they meet, ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-25561-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Clark H. NCDs: a challenge to sustainable human development. Lancet. 2013;381:510–511. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendis S, Davis S, Norrving B. Organizational update: the world health organization global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014; one more landmark step in the combat against stroke and vascular disease. Stroke. 2015;46:e121–122. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arokiasamy P, et al. Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases in 6 Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Findings From Wave 1 of the World Health Organization’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:414–428. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu SS, et al. Outline of the report on cardiovascular disease in China, 2010. Biomed Environ Sci. 2012;25:251–256. doi: 10.3967/0895-3988.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saczynski JS, et al. Patterns of comorbidity in older adults with heart failure: the Cardiovascular Research Network PRESERVE study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:26–33. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, et al. Comorbidity Analysis According to Sex and Age in Hypertension Patients in China. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13:99–107. doi: 10.7150/ijms.13456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koller D, et al. Multimorbidity and long-term care dependency–a five-year follow-up. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf-Maier K, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–2369. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dzudie A, et al. Chronic heart failure, selected risk factors and co-morbidities among adults treated for hypertension in a cardiac referral hospital in Cameroon. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unal S, Acar B, Ertem AG, Sen F. Endocan in Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases. Angiology. 2017;68:85. doi: 10.1177/0003319716658404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendis S. et al. Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Geneva World Health Organization (2011).

- 13.Lehrke M, Marx N. Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure. Am J Med. 2017;130:S40–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segura J, de la Sierra A, Fernandez S, Ruilope LM. Relevance of diabetes in high cardiovascular risk hypertensive patients. Med Clin (Barc) 2013;141:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavie CJ, McAuley PA, Church TS, Milani RV, Blair SN. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases: implications regarding fitness, fatness, and severity in the obesity paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1345–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varbo A, et al. Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arsenault BJ, et al. Beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: respective contributions of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglycerides, and the total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio to coronary heart disease risk in apparently healthy men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;55:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corlateanu A, Covantev S, Mathioudakis AG, Botnaru V, Siafakas N. Prevalence and burden of comorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respir Investig. 2016;54:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonci E, et al. Association of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Subclinical Cardiovascular Changes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:213737. doi: 10.1155/2015/213737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummings DM, et al. Consequences of Comorbidity of Elevated Stress and/or Depressive Symptoms and Incident Cardiovascular Outcomes in Diabetes: Results From the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Diabetes care. 2016;39:101–109. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murad K, et al. Burden of Comorbidities and Functional and Cognitive Impairments in Elderly Patients at the Initial Diagnosis of Heart Failure and Their Impact on Total Mortality: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang Z, et al. Co-occurrence of cardiometabolic diseases and frailty in older Chinese adults in the Beijing Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing. 2013;42:346–351. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clerencia-Sierra M, et al. Multimorbidity Patterns in Hospitalized Older Patients: Associations among Chronic Diseases and Geriatric Syndromes. Plos One. 2015;10:e132909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Organization WH. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Geneva (2011).

- 25.Boyd CM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menendez ME, Ring D. A Comparison of the Charlson and Elixhauser Comorbidity Measures to Predict Inpatient Mortality After Proximal Humerus Fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:488–493. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK. Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: what a difference a decade makes. Circulation. 2011;124:2145–2154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, Ten HM, Boersma E, Peters SA. Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fried TR, et al. The effects of comorbidity on the benefits and harms of treatment for chronic disease: a systematic review. Plos One. 2014;9:e112593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee PG, Cigolle C, Blaum C. The co-occurrence of chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: the health and retirement study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:511–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vetrano DL, et al. Chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: The different weight of comorbidity. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;27:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapsomaniki E, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1·25 million people. Lancet. 2014;383:1899–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60685-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su Y, et al. Association Between Body Mass Index and Diabetes in Northeastern China: Based on Dose-Response Analyses Using Restricted Cubic Spline Functions. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2016;28:486–497. doi: 10.1177/1010539516656436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang SB, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in northeastern China: a cross-sectional study. Public Health. 2015;129:1539–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu J, et al. Optimal cut-off of obesity indices to predict cardiovascular disease risk factors and metabolic syndrome among adults in Northeast China. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1079. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3694-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yip GW, et al. Oscillometric 24-h ambulatory blood pressure reference values in Hong Kong Chinese children and adolescents. J Hypertens. 2014;32:606–619. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Committee CADP. China Adult Dyslipidemia Prevention Guide. Beijing, China: People’s Health Publishing House (2007).

- 39.Zhou B. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2002;23:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang CL, Wang WX, Wu X, Wang BH. Effects of average degree on cooperation in networked evolutionary game. The European Physical Journal B - Condensed Matter and Complex Systems. 2006;53:411–415. doi: 10.1140/epjb/e2006-00395-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harding A. Actor-Network-Theory and Micro-Learning Networks. Educ Prim Care. 2017;28:295–296. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2017.1344882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jimenez CP, et al. Charlson comorbidity index in ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage as predictor of mortality and functional outcome after 6 months. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:e214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.