Abstract

Glycolate oxidase (GOX)-dependent production of H2O2 in response to pathogens and its function in disease resistance are still poorly understood. In this study, we performed genome-wide identification of GOX gene family in Nicotiana benthamiana and analyzed their function in various types of disease resistance. Sixteen GOX genes were identified in N. benthamiana genome. They consisted of GOX and HAOX groups. All but two NbGOX proteins contained an alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain with extra 43–52 amino acids compared to that of FMN-dependent alpha-hydroxyacid oxidizing enzymes (NCBI-CDD cd02809). Silencing of three NbGOX family genes NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 differently affected resistance to various pathogens including Tobacco rattle virus, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Effect of these genes on resistance to Xoo is well correlated with that on Xoo–responsive H2O2 accumulation. Additionally, silencing of these genes enhanced PAMP-triggered immunity as shown by increased flg22-elicited H2O2 accumulation in NbGOX-silenced plants. These NbGOX family genes were distinguishable in altering expression of defense genes. Analysis of mutual effect on gene expression indicated that NbGOX4 might function through repressing NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1. Collectively, our results reveal the important roles and functional complexity of GOX genes in disease resistance in N. benthamiana.

Introduction

Glycolate oxidase (GOX/GLO) is a crucial enzyme in photorespiration, catalyzing the conversion of glycolate into glyoxylate in peroxisomes with the production of H2O21. Photorespiration caused by high light intensity, drought and salinity is one of the essential pathways of plant metabolism and resistance to abiotic stress conditions2, allowing plant growth in a high oxygen-containing environment3. Hydroxy acid oxidase (HAOX) is also located in peroxisomes and has a high similarity to GOX4. Therefore, HAOX is recognized as a subgroup of GOX family hereafter.

GOX genes have been identified in several plant species including Arabidopsis thaliana and rice. A. thaliana contains five GOX family genes, AtGOX1-3 and AtHAOX1-25. The five members of GOX family possess similar size of amino acid (aa) ranging from 364 to 374 and show high similarity among each other. They all carry an alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain. Rice genome comprises four functional GOX/GLO genes and they are differently expressed in rice tissues. Complex interactions exist for GLO isozymes and are coordinately controlled by GLO1 and GLO46. GOX plays roles in a variety of physiological processes. For instance, GOX is required for maize to survive in ambient air7. It is involved in drought and salt stress responses8,9, and has a strong regulation over photosynthesis, possibly through a feed-back inhibition on Rubisco activase10. In addition, a rice GLO appears to affect plant growth11.

Moreover, GOX is supposed to play a crucial role in plant disease resistance. The products from a reaction catalyzed by GOX are glyoxylate and H2O2, both are involved in plant disease resistance. Glyoxylate is an efficient precursor for biosynthesis of oxalate12, which is a key molecule in the interactions between plant and pathogens such as Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Ss)13,14. However, the pathway of oxalate accumulation and regulation seems to be independent of GOX15. As an important reactive oxygen species (ROS), H2O2 functions as an essential signal in the interactions between plant and pathogens16–19. Nevertheless, direct evidence supporting a role of GOX in plant disease resistance has been mainly reported from the studies in the model plant species Arabidopsis, rice and Nicotiana benthamiana to date. Arabidopsis mutants of all five GOX genes show lowered H2O2 accumulation, reduced callose deposition, and decreased electrolyte leakage and accordingly lose the nonhost resistance to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci5, demonstrating that all members of the Arabidopsis GOX family positively function in this nonhost resistance. However, a study in rice showed the opposite results. Chern et al.11 reported that knock-down of a rice GOX gene GLO1 using the constitutive and inducible constructs enhanced rice resistance to another bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) with increased expression of defense regulator genes NH1, NH3 and WRKY45, and thus GOL1 appeared to play a negative role in this host resistance11. In addition, virus induced gene silening (VIGS) analysis of a GOX gene in N. benthamiana indicated its positive role in nonhost resistant to P. syringae pv. tomato and cell death elicited by several R genes such as LOV1, RPP8 and Pto5,20. These results indicate that GOX may play distinct roles in different types of plant disease resistance against various types of pathogens.

In this study, we conducted genome-wide identification of GOX in N. benthamiana and explored the function of three NbGOX genes in various types of resistance. Our results reveal that GOX genes play important roles in various types of resistance including PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI), host and nonhost resistance in N. benthamiana against different pathogens, and members of NbGOX gene family employ distinct defense pathways to modulate disease resistance.

Methods

Identification of N. benthamiana GOX family genes

The protein sequences of Arabidopsis GOX family including three AtGOXs and two AtHAOXs were obtained from TAIR and were then used to BLASTp search against N. benthamiana genome databases in Solanaceae Genomics Network (SGN, http://solgenomics.net/) and University of Sydney (http://sydney.edu.au/science/molecular_bioscience/sites/benthamiana/). All retrieved non-redundant sequences were collected and subjected to domain composition anaysis using Conserved Domain Database (CDD) program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd). Sequences containing a complete alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain were recognized as potential GOX proteins. The N. benthamiana GOX sequences were aligned with Arabidopsis GOXs using ClustalX 2.01 program21 with default settings. The unrooted phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the alignments using MEGA 5.022 with the maximum likelihood (ML) method. The bootstrap analysis was carried out with 1000 replicates. To obtain sequence similarity, GOX family protein sequences in N. benthamiana and A. thaliana were compared using MegAlign program of Lasergene software package.

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) analyses

The coding regions of the NbGOX genes are highly conserved. To ensure the specificity of gene silencing, the VIGS target fragment of NbHAOX8 (Nbv5tr6245008) and NbGOX1 (NbS00060838g0004.1) were designed to a 203 and 243 bp fragemnt of 3′ UTR region while that of NbGOX4 (NbS00005125g0015.1) corresponded to a 334 bp fragment of 5′ UTR region. The cloning sites BamHI and EcoRI were added to the end of the forward and reverse primers for target fragment amplification, respectively. The PCR product was ligated into pYL156 with BamHI and EcoRI, and confirmed by sequencing. The recombinant constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporating. Agroinfiltration and VIGS analyses were conducted as described23,24 except that recombinant pYL156 with insertion of an eGFP fragment instead of an empty pYL156 was used as control to alleviate viral symptom25. The first and second true leaves of N. benthamiana plants at four-leaf stage were infiltrated with the mixture at 1:1 ratio of Agrobacterium cell suspensions carrying pTRV1 and recombinant pYL156, respectively, and the agro-inoculated plants were grown in a plant growth chamber at 21 °C with a 16 h/8 h light/dark daily cycle to ensure the silencing efficiency. Three weeks post agro-inoculation, these plants were subjected to phenotype investigation and functional analyses.

Plant materials for gene exression analyses

For analysis of NbGOX gene expression in response to pathogen inoculation, N. benthamiana were grown in pots in growth chambers at 25 °C with 16 h/8 h light/dark daily cycle. The completely developed leaves of 8-leaf-old plants were inoculated with Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) by infiltrating with bacterial suspensions with an OD600 of 0.5. The inoculated leaves were sampled at 0, 1, 6 and 24 h post inoculation (hpi). The harvested samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. For analysis of the VIGS efficiency and defense gene expression in VIGS-treated plants, the leaves were collected at 21 d after agro-infiltration.

Gene expression analysis with quantitative real time PCR

RNA extraction and quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses and consequent statistical data analyses were conducted as described26. The primers for amplification of the NbGOX genes were designed from the 5′ UTR regions to ensure the gene targeting specificity for single genes. The N. benthamiana homologs of rice WRKY45 and WRKY62 which are involved in defense against Xoo27,28 was identified by BLASTp and phylogenetics analyses. The 18 S rDNA gene was used as a loading check. All primers used in qRT-PCR analyses were listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Plant disease resistance analysis

Disease resistance was evaluated in the newly, fully expanded leaves of VIGS-treated plants at 21 d after agro-infiltration. Leaf inoculation with Xoo was condected as described29. Xoo was incubated in NA liquid media containing carbenicillin (50 μg/ml). Leaves were inoculated by infiltrating with bacterial suspensions with an OD600 of 0.5. The inoculated plants were grown at 25 °C in a growth chamber. Hypersensitive response (HR) was recorded and leaves were classified into three categories according to the percentage of hypersentitive necrosis area over the total inoculated area as described30. Bacterial numbers in the inoculated areas were counted as described29. Leaf inoculation with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Ss) was performed with mycelial plugs as described31, except for that mycelial plugs of 5 mm in diameter were used. Size of disease lesions was measured. For each treatment, at least 6 leaves from 6 silenced plants (one leaf from each plant) were examined. Each experiment was conducted three times independently.

H2O2 assays

The H2O2 in Xoo-inoculated leaves was detected in situ using diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining as described19. The H2O2 elicited by the PAMP peptide flg22 (400 nM) in leaf discs were quantitatively measured using a Microplate Luminometer (Orion L Microplate Luminometer, Titertek-Berthold, Germany) following previously described protocol31. For each treatment, 8 leaves were collected. The experiments were conducted three times independently.

Statistical data analysis

All experiments were conducted independently three times. Analysis of variance was performed using the SPSS software (Version 19.0, IBM, USA). Significance of the differences between mean values was determined with Student’s t test (p < 0.05) and Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT, p < 0.05).

Results

Identification of GOX family genes in N. benthamiana genome

To identify GOX family genes in N. benthamiana genome, BLASTp search was performed for five Arabidopsis GOX family protein sequences including three AtGOXs and two AtHAOXs against the N. benthamiana genome databases in SGN (http://solgenomics.net/) and University of Sydney (http://sydney.edu.au/science/molecular_bioscience/sites/benthamiana/), respectively. Consequently, 10 and 22 candidate sequences were retrieved from the SGN database and University of Sydeny database, respectively. Further domain composition analysis using CDD program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd) demonstrated that 9 and 7 candidate genes from the SGN database and Sydeny database, respectively, contained an alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain, a characteristic domain for all Arabidopsis GOX proteins. These 16 sequences were recognized as GOX family genes. Sequence alignment analysis indicated that 6 out of 7 sequences from University of Sydney database showed high similarity to AtHAOXs, while 9 sequences from SGN database displayed similarity to both AtGOXs and AtHAOXs. It’s notable that one sequence from SGN (NbS00018477g0026.1) comprised of 836 aa with two alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domains. Further protein sequence alignment of this candidate with AtGOXs suggested that it was a fusion of two NbHAOXs with 337 aa and 499 aa, respectively (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S1).

Table 1.

The GOX gene family in Nicotiana benthamiana.

| Gene | Locus number* | Protein size (aa) |

Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| NbGOX1 | NbS00060838g0004.1 | 368 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbGOX2 | Nbv5tr6239807 | 368 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbGOX3 | NbS00022202g007.1 | 333 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbGOX4 | NbS00005125g0015.1 | 356 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbGOX5 | NbS00025736g0004.1 | 356 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbGOX6 | NbS00024535g0016.1 | 349 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbGOX7 | NbS00043092g0003.1 | 384 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX1 | NbS00018477g0026.1-(338-836) | 499 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX2 | Nbv5tr6233382 | 363 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX3 | NbS00001920g0010.1 | 294 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX4 | Nbv5tr6245007 | 363 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX5 | Nbv5tr6211426 | 302 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX6 | NbS00018477g0026.1-(1-337) | 337 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX7 | Nbv5tr6200247 | 364 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX8 | Nbv5tr6245008 | 363 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX9 | NbS00010324g0011.1 | 363 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

| NbHAOX10 | Nbv5tr6245006 | 364 | alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN |

*Genes with a number starting with NbS are from the database of Solanaceae Genomics Network while those starting with Nbv5 are from the database of University of Sydney.

Bioinformatics analyses predicted that NbGOXs were basic proteins with a size of 294 aa (NbHAOX3) ~480 aa (NbHAOX1) that was dominated by about 360 aa (Table 1). It is noteworthy that domain prediction analysis using NCBI-CDD indicated that the alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain of all the identified N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis GOX sequences except NbHAOX3 and NbHAOX6 contained an extra fragment in the middle compared with that of FMN-dependent alpha-hydroxyacid oxidizing enzymes deposited in NCBI-CDD (cd02809). The size of this extra fragment was 43 aa for HAOXs while 46 aa for GOXs, expect AtGOX2 (AT3G14415.2) whose was 52 aa (Supplementary Fig. S1). Function of this extra fragment was unclear. Sequences of the NbGOX family showed a high similarity within groups but displayed much lower similarity between groups. The protein sequence similarity was 73.0–99.7% within the NbGOX group while 74.1–98.9% within NbHAOX group, whereas only 45.4–60.9% between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. S2). CDD analyses demonstrated that all Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana GOX family proteins carried 3 putative catalytic residues, and most of them harbored 9 active sites, 5 subtrate binding sites and 7 FMN binding sites. The extra fragment appeared after the second putative catalytic residues (Supplementary Fig. S1). To better reflect the orthologous relationship between the N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis GOX genes, we named the N. benthamiana members in accordance with the phylogeny and sequence similarity to individual Arabidopsis GOXs (Table 1, Fig. 1).

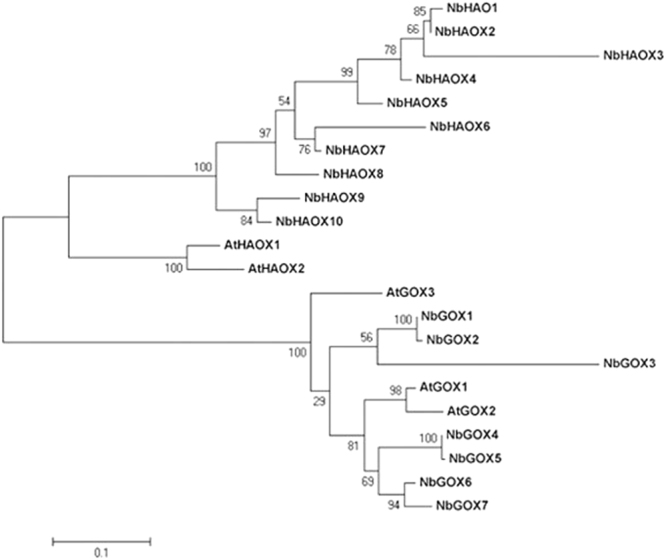

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of GOX family proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana. The tree was created using Clustalx program by maximum liklihood method with bootstrap of 1000 in MEGA5. The protein sequences are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1.

Phylogenetic relationship between N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis GOXs

The full-length amino acid sequences of N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis GOXs were subjected to phylogenetic analysis. The ML phylogenetic tree showed that alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain-containing proteins were divided into two major groups, group GOX and group HAOX (Fig. 1). All NbGOXs were from SGN database except NbGOX2, while NbHAOX sequences were from both SGN and University of Sydney databases. HAOX sequences from N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis were separated into two clades, while GOX sequences from the two species not, suggesting that HAOXs from the two species are more distant evolutionarily compared with GOXs.

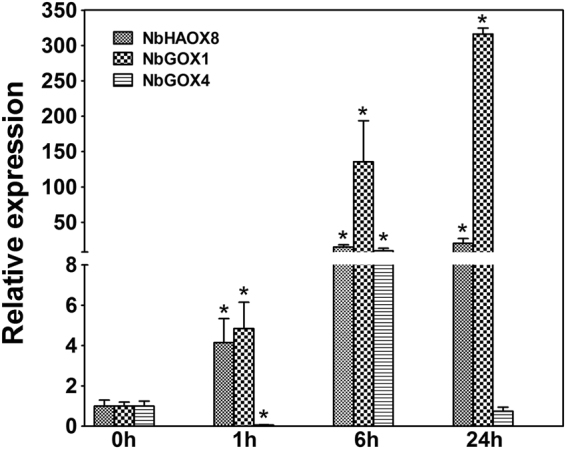

NbGOX genes are differentially expressed in response to the nonhost pathogen Xoo in N. benthamiana

Three GOX family genes, NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4, each representing a N. benthamiana homolog of three clades of AtGOX family (AtHAOX1/AtHAOX2, AtGOX1/AtGOX2, and AtGOX3) in the ML phylogenetic treee, were selected for the analysis of their expression in response to inoculation with the nonhost pathogen Xoo. qRT-PCR analysis using gene specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) demonstrated that the expression patterns were distinct between the three selected GOX family genes in response to Xoo. Expression of NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 was induced as early as 1 h post inoculation (hpi) and consistently increased henceforth but with different magnitude, by 20.2- and 316.2-fold, respectively, at 24 hpi compared with that at 0 hpi, while expression of NbGOX4 was strongly suppressed at 1 hpi, significantly induced by 9.7-fold at 6 hpi, and then dropped to basal level at 24 hpi compared with that at 0 hpi (Fig. 2). This result indicates that these GOX family genes may play different roles in nonhost defense responses to Xoo in N. benthamiana.

Figure 2.

Expression of three NbGOX family genes NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 in N. benthamiana in response to Xoo inoculation. Gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR with gene-specific primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Significant difference between expression values at various timepoints and that at 0 hpi is indicated as a “*”(p < 0.05, Student’s t test). Data represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments.

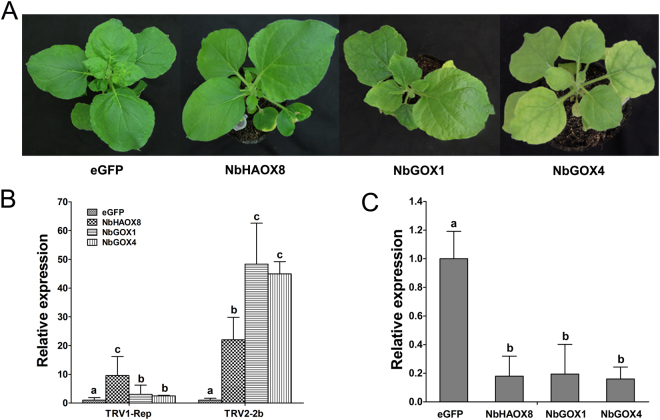

Silencing of N. benthamiana GOX genes significantly reduces resistance to viral pathogen TRV

To probe the function of NbGOX family genes, VIGS analyses were performed individually for NbHAOX8, NbGOX4 and NbGOX1. To ensure the specificity of gene silencing, the primers used for making VIGS construct were designed at the gene specific UTR sequences of these single genes (Supplement Table 1). The VIGS fragments were ligated into the TRV silencing vector pYL156 for silencing analyses, and non-silenced eGFP fragment-inserted pYL156 vector was used as a negative control25. Three weeks after silencing treatment, plants of eGFP control showed no or only very mild mosaic symptoms in some leaves, while those VIGS-treated for NbGOX4, NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 showed different degree of yellowing symptoms and/or retarded growth. NbHAOX8-silenced plants exhibited no obvious yellowing symptoms but showed retarded growth with less leaves; NbGOX1-silenced plants displayed mild yellowing symptoms and retarded growth with less leaves, while NbGOX4-silenced plants exhibited strong yellowing symptoms but showed no retarded growth (Fig. 3A). This result suggests that these NbGOX family genes may slightly affect plant growth.

Figure 3.

Silencing of NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 reduced resistance to TRV in N. benthamiana. (A) Phenotypes of the gene-silenced plants. Gene silencing analyses were performed using TRV-based vectors. Photographs were taken at 3 weeks post agro-infiltration. (B) Detection of transcripts of the TRV1 replicase and TRV2 2b genes in gene-silenced plants by qRT-PCR. (C) Evaluation of gene silencing efficiency. Gene expression was examined by qRT-PCR. Significant difference between expression values in gene-silenced plants and eGFP control plants is indicated as different lowercase letters (P < 0.05, DMRT).

To examine effect of VIGS treatment on resistance to the virus TRV, accumulation of viral component gene transcripts in VIGS treated plants and eGFP control plants was comparatively analyzed by qRT-PCR. Result showed that transcripts of TRV1 replicase and TRV2 2b genes accumulated 9- and 22-fold higher in NbHAOX8-silenced plants while over 3- and 44-fold in NbGOX1- and NbGOX4-silenced plants, respectively, compared with eGFP-control plants (Fig. 3B). This result indicates that these GOX family genes may positively affect plant resistance to TRV.

To clarity whether the phenotypes were attributed to silencing of these NbGOX family genes, silencing efficiency of the VIGS treatments were monitored by detecting the transcripts of these genes in the agro-infiltrated plants with qRT-PCR. qRT-PCR results showed that the transcripts of all three NbGOX family genes in the agro-infiltrated plants dropped to lower than 20% of that in eGFP-control plants (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that all three genes in the VIGS treated plants had been efficently silenced. Collectively, N. benthamiana GOX family genes NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 play a positive role in resistance to TRV.

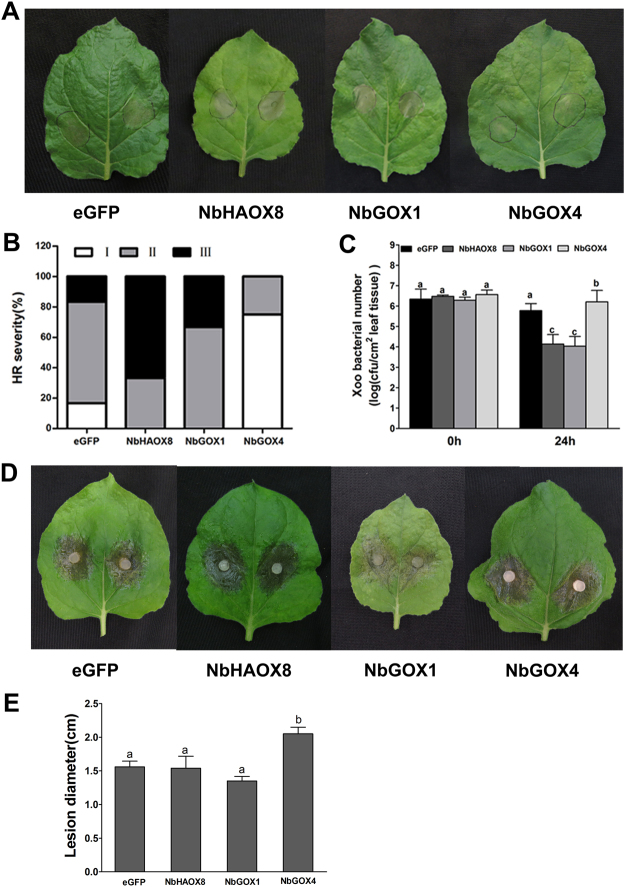

Silencing of N. benthamiana GOX genes alters nonhost resistance to Xoo

To understand the role of NbGOX family genes in nonhost resistance, the silenced N. benthamiana plants were inoculated with the nonhost pathogen Xoo. The HR necrosis of leaves of NbHAOX8- and NbGOX1-silenced plants was obviously more severe while that of the NbGOX4-silenced plants was weaker than that of the eGFP-control plants (Fig. 4A). At 18 hpi, 67% and 33% leaves of NbHAOX8- and NbGOX1-silenced plants, respectively, exhibited complete or nearly complete HR necrosis (type III), this percentage for the eGFP-control plants was 17%, while no leaf of NbGOX4-silenced plants displayed this type of HR (Fig. 4B). Further, bacterial number counting assay demondtrated that Xoo bacterial number in inoculated areas of NbHAOX8- and NbGOX1-silenced plants was reduced by near 2 orders of magnitude while that of NbGOX4-silenced plants increased by 0.4 orders of magnitude compared with that of the eGFP-control plants at 24 hpi (Fig. 4C). Together, these results indicate that NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 play a negative role while NbGOX4 plays a positive role in nonhost resistant to Xoo.

Figure 4.

Silencing of NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 differently affected resistance to Xoo and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in N. benthamiana. Disease resistance was evaluated in the newly, fully expanded leaves of VIGS-treated plants at 21 d after agro-inoculation. For each treatment, at least 6 leaves from 6 silenced plants (one leaf from each plant) were examined. Each experiment was conducted three times independently. (A) Symptoms of Xoo-induced HR in the gene-silenced plants. Photographs were taken at 18 hpi. (B) Severity of Xoo-induced HR in the gene-silenced plants at 18 hpi. HR is classified based on the intensity of cell death in inoculated areas: I, HR area smaller than 30% of infiltrated leaf area; II, HR area larger than 30% but smaller than 90% of infiltrated leaf area; III, HR area larger than 90% of the infiltrated leaf area. HR severity is indicated as the percentage of leaves exhibiting HR over total infiltrated leaves. (C) Statistical analysis of Xoo bacterial number in the infiltrated areas at 0 and 24 hpi. Data were analyzed using SPSS. Significant difference is indicated as different lowercase letters (P < 0.05, DMRT). (D) Disease symptoms of the gene-silenced plants after inoculation with Ss. Photographs were taken at 26 hpi. (E) Statistical analysis of lesion diameter. Significant difference of lesion diameter is indicated as lowercase letters (P < 0.05, DMRT).

Silencing of N. benthamiana GOX genes changes host resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

To explore the role of NbGOX genes in resistance to fungal pathogen, the silenced N. benthamiana plants were inoculated with the necrotrophic fungal pathogen Ss. NbHAOX8-silenced plants displayed similar size of lesions to the eGFP-control plants, NbGOX1-silenced plants exhibited smaller lesions, while NbGOX4-silenced plants showed larger lesions than the eGFP-control plants (Fig. 4D). The average lesion size of NbHAOX8-, NbGOX1- and NbGOX4-silenced plants was 1.54, 1.35 and 2.05 cm in diameter, respectively, at 24 hpi (Fig. 4E), which was in turn statistically similar to, smaller and larger than the lesion size of the eGFP-control plants (1.56 cm on average) (Fig. 4E). This suggests that NbGOX1 may play a negative role while NbGOX4 plays a positive role in basal resistance to the necrotrophic pathogen Ss. However, NbHAOX8 might not contribute to this basal resistance.

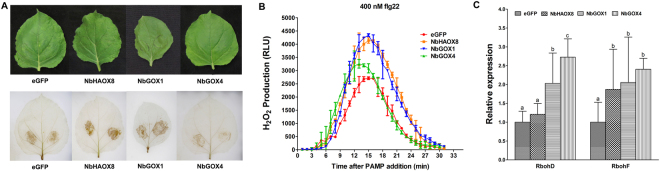

Silencing of N. benthamiana GOX genes modulates pathogen- and PAMP-elicited reactive oxygen species

ROS is essential in resistance to Xoo and Ss in N. bemthaniana13,19. To probe the contribution of ROS to the NbGOX-mediated resistance, H2O2 accumulation in silenced and control plants was compared. DAB staining assay showed that H2O2 accumulated more highly in Xoo-inoculated areas of NbHAOX8- and NbGOX1-silenced plants while more weakly in those of NbGOX4-silenced plants than in those of the eGFP-control plants at 12 hpi, a timepoint when HR had not yet occurred (Fig. 5A). This result indicates that NbGOX family genes might modulate ROS accumulation in resposne to pathogen thereby alter resistance.

Figure 5.

Silencing of NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 differently modulated H2O2 in N. benthamiana. (A) Detection of Xoo-elicited H2O2 in gene-silenced plants at 12 hpi by DAB staining. No HR occurred in these plants (upper panel). (B) Dynamics of H2O2 accumulation in response to flg22 (400 nM) elicitation in leaves of gene-silenced plants. Flg22-triggered H2O2 bursts were measured using luminol-based assay in leaf discs. Data are shown as relative luminal units (RLU) and represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. (C) Effect of silencing of NbHAOX and NbGOX genes on expression of RbohD and RbohF genes. Gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. Significant difference between expression values is indicated as lowercase letters (P < 0.05, DMRT).

The ROS accumulation is also a hallmark of pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggeted immunity (PTI). To examine the role of NbGOX genes in PTI, effect of silencing of NbGOX genes on PAMP-elicited ROS accumulation was monitored. Flg 22 (400 nM) were applied to leaf discs (4 mm in diameter) and the dynamics of H2O2 accumulation was measured. Quantitative detection by luminol-based approach demonstrated that, for the eGFP-control plants, H2O2 increased rapidly and peaked at 15 min in response to flg22 and then decreased quickly to reach the basal level within about 30 min. However, NbGOX-silenced plants showed different flg22-elicited H2O2 accumulation compared with the eGFP-control plants. Upon flg22 supply, luminol-based signal repersenting H2O2 accumulation in NbHAOX8-, NbGOX1- and NbGOX4-silenced plants culminated at 4139, 4342 and 3257 RLU, respectively, which was stronger than that in the eGFP-control plants (2710 RLU) (Fig. 5B). This result implies that NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 might play a negative role in flg22-triggered PTI and NbGOX4 might function similarly but to a less level.

Silencing of N. benthamiana GOX genes does not significantly change expression of NADPH oxidases genes

Plant Rboh gene family encodes subunits of NADPH oxidase. This family, especially RbohD and RbohF, is an important source to generate ROS during the interactions between plant and pathogens16,32. To clarify whether NbGOX genes modulate ROS accumulation via Rboh genes, effect of NbGOX gene silencing on the expression of RbohD and RbohF genes was examined. qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression of RbohD and RbohF genes in the three NbGOX-silenced plants was higher to different extent than that in the eGFP control plants (Fig. 5C). In NbHAOX8-silenced plants, expression of RbohD and RbohF genes was 1.2-fold and 1.8-fold, respectively, as high as that in control plants. In NbGOX1-silenced plants, expression of both Rboh genes was about 2-fold as high as that in control plants; while in NbGOX4-silenced plants, expression of RbohD and RbohF genes was 2.7-fold and 2.4-fold, respectively, as high as that in control plants (Fig. 5C). Influence of change of the Rboh gene expression at these levels (less than 3-fold) on ROS generation and accumulation awaits further elucidation.

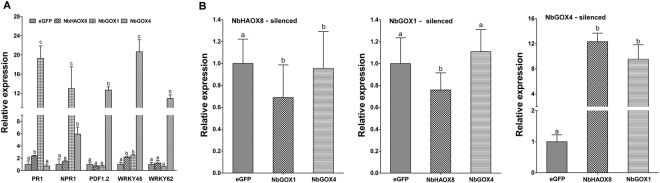

Silencing of N. benthamiana GOX genes in plants strongly and differently alters expression of defense-related genes

To further study the molecular mechanisms underlying NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4-mediated plant resistance, we monitored the expression of genes involved in defense against pathogens including Xoo, such as PR1, NPR1, WRKY45 and WRKY6227,28, in gene-silenced plants. The qRT-PCR analysis showed that expression of all the five genes was not obviously changed in NbHAOX8-silenced plants compared to that in the eGFP control plants. However, expression of these genes was significantly altered in the other two NbGOX-silenced plants. Compared with the eGFP control plants, expression of PR1, NPR1, and WRKY45 increased by 19-, 13- and 2.4-fold, respectively, whereas expression of PDF1.2 and WRKY62 decreased by 26% and 42% in NbGOX1-silenced plants. In NbGOX4-silenced plants, expression of NPR1, PDF1.2, WRKY45 and WRKY62 was enhanced by 6-, 12-, 20- and 10-fold, respectively, while expression of PR1 was reduced by 38% (Fig. 6A). These demonstrate that silencing of NbGOX1 strongly enhances expression of PR1 and NPR1 while obviously reduces that of WRKY62; silencing of NbGOX4 strongly increases expression of NPR1, PDF1.2, WRKY45 and WRKY62 while decreases that of PR1, whereas silencing of NbHAOX8 does not obviously alter expression of all five checked genes. This indicates that NbGOX1-dependent resistance may involve salicylic acid (SA) and WRKY62-mediated pathways; NbGOX4-dependent resistance may relate to jasmonic acid (JA), WRKY45- and WRKY62-mediated pathways, while NbHAOX8-dependent resistance may be linked to pathways unrelated with these checked genes.

Figure 6.

Silencing of NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 differently altered defense related genes and other member genes of NbGOX family in N. benthamiana. (A) Expression profiles of PR1, NPR1, PDF1.2, WRKY45 and WRKY62 genes in gene-silenced plants. (B) Mutual gene expression modulation of NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4. Expression of the other two genes in single GOX gene-silenced plants was examined by qRT-PCR. Data represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. Significant difference between expression values is indicated as different lowercase letters (P < 0.05, DMRT).

NbGOX4 might function through suppressing NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1

NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 are all involved in ROS and resistance, which prompted us to examine the mutual influence of these genes. We analyzed the effect of silencing of one gene on expression of the remaining two genes. Result showed that silencing of NbHAOX8 or NbGOX1 individually did not strikingly alter expression of the other two genes, while silencing of NbGOX4 strongly enhanced expression of NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 genes by approximately 12- and 9-fold, respectively (Fig. 6B). This result implies that NbGOX4 might function through suppressing NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1.

Discussion

The alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain of GOX family in plants

In this study, we identified 16 GOX family genes including 7 GOX and 9 HAOX genes in N. benthamiana genome (Table 1). Both GOX and HAOX proteins possess an alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain and have a similar size (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S1), yet, they clustered in distinct groups in the ML phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). Interestingly, except NbHAOX3 and NbHAOX6, the alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain of all N. benthamiana GOX family sequences identified in this study and Arabidopsis GOX family sequences identified previously5 contained an extra fragment after the second putative catalytic residues compared with that of FMN-dependent alpha-hydroxyacid oxidizing enzymes deposited in NCBI-CDD (cd02809). It is noteworthy that the size of this extra fragment was conserved within HAOX and GOX subfamilies (Supplementary Fig. S1). According to the annotation of cd02809, family of FMN-dependent alpha-hydroxyacid oxidizing enzymes occurs in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Members of this family include flavocytochrome b2 (FCB2), glycolate oxidase (GOX), lactate monooxygenase (LMO), mandelate dehydrogenase (MDH), and long chain hydroxyacid oxidase (LCHAO). Containing an extra fragment in the middle of the alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain may be a characteristic feature of plant GOX group of the whole family of FMN-dependent alpha-hydroxyacid oxidizing enzymes. Function of this extra fragment in GOX enzymes remains to be explored.

Function of GOX in disease resistance in N. benthamiana

Role of GOX in plant disease resistance is seldom studied to date. Attention on this area is not attracted untill recently Rojas et al.5 found that an NbGOX gene played a positive role in nonhost resistant to P. syringae pv. tomato when they conducted VIGS screening for resistance regulatory genes in N. benthamiana5. They further revealed that all five members of the Arabidopsis GOX family positively function in nonhost resistance to P. syringae pv. tabaci. Meanwhile, Chern et al.11 silenced a rice GOX gene GLO1 in rice by using the constitutive and inducible construct, and found that GLO1 appeared to play a negative role in rice resistance to Xoo11. In addition, Gilbert and Wolpert20 reported a GOX gene in N. benthamiana played a positive role in cell death triggered by R genes such as LOV1, RPP8 and Pto20. In the present study, we analysed function of three representative GOX family genes NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 in N. benthamiana through VIGS. We found that all three genes play a positive role in resistance to TRV (Fig. 3), but they differently contribute to nonhost resistant to Xoo and basal resistant to the necrotrophic pathogen Ss (Fig. 4). Furthermore, we for the first time examined the role of GOX in PTI through detecting the flg22-elicited ROS accumulation, and found that NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 might play a stronger negative role while NbGOX4 play a weaker negative role in flg22-triggered immunity (Fig. 5B). Our results clearly show that unlike Arabidopsis GOXs, which although have divergent functions in the photorespiratory pathway33, all function similarly and additively in nonhost resistance5, members of GOX family in N. benthamiana play distinct roles in resistance to the same pathogens and in immunity triggered by the same elicitors. Moreover, one GOX family gene in N. benthamiana might play distinct roles in different types of resistance (host basal resistance, nonhost resistance and PTI) against different types of pathogens. Collectivelly, these reveal that GOX family genes are involved in various types of disease resistance and this function of GOX family genes may differ up to plant species, gene members, types of resistance and pathogens/elicitors.

Functional mechanisms of GOX in disease resistance in N. benthamiana

It is conceivable that the most direct mechanism underlying GOX-mediated resistance should be modulating H2O2 during the interactions between plant and pathogen. Our DAB staining results clearly showed that silencing of NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 increased while silencing of NbGOX4 reduced Xoo-elicited H2O2 accumulation, demonstrating that NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 play a negative role while NbGOX4 plays a positive role in this H2O2 accumulation (Fig. 5A). Effect of these genes on Xoo–responsive H2O2 accumulation was well correlated with that on resistance to Xoo (Fig. 4). Considering that H2O2 is indisapensible for the nonhost resistance to Xoo in N. benthamiana19, this result implies that these GOX family genes alter resistance via modulating H2O2 accumulation. Moreover, examination of the role of GOX in PAMP elicited ROS demonstrated that NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 and probably also NbGOX4 might play a negative role in flg22-elicited ROS (Fig. 5B). Our results reveal that GOX family regulates H2O2 accumulation not only during nonhost resistance nut also during PTI. In this context, it is interesting that rice GLO1 was found to interact with a glutaredoxin protein34. How NbGOX family proteins coordinate with other components to regulate cellular redox awaits further dissection.

A well-known mechanism to generate ROS during the interactions between plant and pathogen is from NADPH oxidase encoded by Rboh genes in plants, especially RbohD and RbohF16,18,32,35. It was reported that, In Arabidopsis, GOX and Rboh function independently in regulating ROS during nonhost resistance5. Whether this is also the case for GOX in N. benthamiana deserves to be elucidated. We monited the expression of RbohD and RbohF in GOX-silenced plants, and found that silencing of three NbGOX family genes increased expression of the two Rboh genes to 1.2~2.7-fold as high as that in control plants (Fig. 5C). It is unclear whether change of the Rboh gene expression at this level (less than 3-fold) significantly influences ROS generation and accumulation. Therefore, it remains to be clarified whether NbGOX genes modulate ROS accumulation through altering RbohD and RbohF gene expression.

In addition to differently modulate ROS accumulation, the three NbGOX family genes NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 promote different defense signaling pathways. Our qRT-PCR results showed that silencing of NbGOX1 strongly increased the expression of PR1 and NPR1, silencing of NbGOX4 significantly promoted the expression of NPR1, PDF1.2, WRKY45 and WRKY62, while silencing of NbHAOX8 did not obviously alter expression of all 5 checked genes (Fig. 6A). PR1 and PDF1.2 are well known marker genes of SA and JA defense signaling pathways, while WRKY45 and WRKY62 are important defense regulatory genes involved in resistance to a variety of pathogens including Xoo27,28,36–39. Our results indicate that NbGOX1 negatively regulate SA pathway, NbGOX4 negatively modulate JA and WRKY45- and WRKY62-mediated pathways; while NbHAOX8 might involve pathways unrelated with these checked genes. These differences may partially explain why these NbGOX family genes differently modulate the disease resistance. Additionally, our result is different from what has been reported for Arabidopsis HAOX2, which activates the SA pathway and is mediated by PAD4, NPR1, and PR-1, based on the comparative expression of these genes in Col-0 and haox2 mutant after inoculation with the nonhost pathogen P. syringae pv. tabaci5. This might relect the difference between constitutive and pathogen responsive expression of GOX family genes. Alternatively, GOX family genes in Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana might have distinct mechanisms to regulate plant defense against pathogens.

Finally, our results on analysis of the mutual effect of the three NbGOX family genes on gene expression showed that silencing of NbHAOX8 or NbGOX1 individually did not obviously alter expression of the other two genes, while silencing of NbGOX4 strongly increased expression of NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 genes (Fig. 6B), indicating that NbGOX4 might function through repressing NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1. This result coincides with the obersavations that NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1 often function similarly in H2O2 accumulation and diseasae resistance in opposite to NbGOX4. Moreover, interactions between members of GOX family have been reported for isozymes of rice GLOs6.

Conclusions

Glycolate oxidase (GOX) gene family in Nicotiana benthamiana was identified at genome-wide level and their function in disease resistance was analyzed. N. benthamiana genome contained 16 GOX genes, which was much more than Arabidopsis and rice. The alpha_hydroxyacid_oxid_FMN domain in all but two currently identified GOX family proteins contained an extra 43–52 amino acids compared with that of FMN-dependent alpha-hydroxyacid oxidizing enzymes deposited in NCBI-CDD (cd02809), and may represent a characteristic feature of plant GOX subfamily of these enzymes. Three NbGOX family genes NbHAOX8, NbGOX1 and NbGOX4 played distinct roles in nonhost resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, host resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and flg22-triggered immunity. This reveals that GOX family genes are involved in various types of disease resistance and this function of GOX family genes may differ up to plant species, gene members, types of resistance and pathogens/elicitors. These NbGOX family genes altered resistance via modulate H2O2 accumulation. Additionally, members of NbGOX family involved distinct defense pathways to affect disease resistance, and NbGOX4 may function through repressing NbHAOX8 and NbGOX1. Collectively, our results reveal that NbGOX family genes play important roles in various types of disease resistance and functions and mechanisms of family members in resistance are distinguishable.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos 31672014 and 31371892), the Genetically Modified Organisms Breeding Major Projects (no. 2014ZX0800905B), and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (no. LZ18C140002).

Author Contributions

J.Y. and Y.P.X. conducted the experiments, designed and analyzed all statistical data. X.Z.C. conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination. X.Z.C., Y.P.X. and H.R. prepared the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-27000-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Foyer CH, Bloom AJ, Queval G, Noctor G. Photorespiratory metabolism: genes, mutants, energetics, and redox signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009;60:455–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.091948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wingler A, Lea PJ, Quick WP, Leegood RC. Photorespiration: metabolic pathways and their role in stress protection. Philos. T. R. Soc. B. 2000;355:1517–1529. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florian A, Araujo WL, Fernie AR. New insights into photorespiration obtained from metabolomics. Plant Biol. 2013;15:656–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reumann S, Ma CL, Lemke S, Babujee L. AraPerox. A database of putative Arabidopsis proteins from plant peroxisomes. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:2587–2608. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.043695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojas CM, et al. Glycolate oxidase modulates reactive oxygen species-mediated signal transduction during nonhost resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:336–352. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.093245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, et al. Glycolate oxidase isozymes are coordinately controlled by GLO1 and GLO4 in rice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelitch I, Schultes NP, Peterson RB, Brown P, Brutnell TP. High glycolate oxidase activity is required for survival of maize in normal air. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:195–204. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.128439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moran JF, et al. Drought induces oxidative stress in pea-plants. Planta. 1994;194:346–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00197534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin CC, Kao CH. Effect of NaCl stress on H2O2 metabolism in rice leaves. Plant Growth Regul. 2000;30:151–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1006345126589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu H, et al. Inducible antisense suppression of glycolate oxidase reveals its strong regulation over photosynthesis in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:1799–1809. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chern MS, Bai W, Chen XW, Canlas PE, Ronald PC. Reduced expression of glycolate oxidase leads to enhanced disease resistance in rice. Peer J. 2013;1:e28. doi: 10.7717/peerj.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu L, et al. Glyoxylate rather than ascorbate is an efficient precursor for oxalate biosynthesis in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2010;61:1625–1634. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams B, Kabbage M, Kim HJ, Britt R, Dickman MB. Tipping the balance: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum secreted oxalic acid suppresses host defenses by manipulating the host redox environment. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002107. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster J, Kim HU, Nakata PA, Browse J. A previously unknown oxalyl-CoA synthetase is important for oxalate catabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1217–1229. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu HW, et al. Oxalate accumulation and regulation is independent of glycolate oxidase in rice leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:1899–1908. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki N, et al. Respiratory burst oxidases: the engines of ROS signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011;14:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pastor V, et al. Fine tuning of reactive oxygen species homeostasis regulates primed immune responses in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013;26:1334–1344. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-13-0117-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheler C, Durner J, Astier J. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in plant biotic interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013;16:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Xu YP, Yang J, Chen GY, Cai XZ. Hydrogen peroxide is indispensable to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae-induced hypersensitive response and nonhost resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2015;44:611–617. doi: 10.1007/s13313-015-0376-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert BM, Wolpert TJ. Characterization of the LOV1-mediated, victorin-induced, cell-death response with virus-induced gene silencing. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013;26:903–917. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-13-0014-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang CC, Cai XZ, Wang XM, Zheng Z. Optimisation of Tobacco rattle virus-induced gene silencing in. Arabidopsis. Funct. Plant Biol. 2006;33:347–355. doi: 10.1071/FP05096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai XZ, et al. Efficient gene silencing induction in tomato by a viral satellite DNA vector. Virus Res. 2007;125:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng WS, Xu QF, Li F, Xu YP, Cai XZ. Establishment of a suitable control vector for Tobacco rattle virus-induced gene silencing analysis in Nicotiana benthamiana. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Agri. & Life Sci.) 2012;38:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and functional analyses of calmodulin genes in Solanaceous species. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng Y, et al. OsWRKY62 is a negative regulator of basal and Xa21-mediated defense against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice. Mol. Plant. 2008;1:446–458. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao Z, et al. A pair of allelic WRKY genes play opposite roles in rice-bacteria interactions. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:936–948. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.145623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li W, et al. Identification of genes required for nonhost resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae reveals novel signaling components. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu QF, et al. Identification of genes required for Cf-dependent hypersensitive cell death by combined proteomic and RNA interfering analyses. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:2421–2435. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saand MA, Xu YP, Li W, Wang JP, Cai XZ. Cyclic nucleotide gated channel gene family in tomato: genome-wide identification and functional analyses in disease resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:303. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres MA, Dangl JL, Jones JD. Arabidopsis gp91phox homologues AtrbohD and AtrbohF are required for accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant defense response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:517–522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012452499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerchev P, et al. Lack of GLYCOLATE OXIDASE1, but not GLYCOLATE OXIDASE2, attenuates the photorespiratory phenotype of CATALASE2-deficient Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:1704–1719. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seo YS, et al. Towards establishment of a rice stress response interactome. PLoS Gen. 2011;7:e1002020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres MA, Dangl JL. Functions of the respiratory burst oxidase in biotic interactions, abiotic stress and development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2005;8:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao P, Duan M, Wei C, Li Y. WRKY62 transcription factor acts downstream of cytosolic NPR1 and negatively regulates jasmonate-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:833–842. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimono M, et al. Rice WRKY45 plays a crucial role in benzothiadiazole-inducible blast resistance. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2064–2076. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim KC, Lai Z, Fan B, Chen Z. Arabidopsis WRKY38 and WRKY62 transcription factors interact with histone deacetylase 19 in basal defense. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2357–2371. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hosur Gnanaprakash P, et al. Association between accumulation of allene oxide synthase activity and development of resistance against downy mildew disease of pearl millet. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;40:6821–6829. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2799-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.