Abstract

Many environmental, host, and microbial characteristics have been recognized as risk factors for dissemination of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB). However, there are few population-based studies investigating the association between the primary sites of tuberculosis (TB) infection and mortality during TB treatment. De-identified population-based surveillance data of confirmed TB patients reported from 2009 to 2015 in Texas, USA, were analyzed. Regression analyses were used to determine the risk factors for EPTB, as well as its subsite distribution and mortality. We analyzed 7007 patients with exclusively pulmonary TB, 1259 patients with exclusively EPTB, and 894 EPTB patients with reported concomitant pulmonary involvement. Age ≥45 years, female gender, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive status, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) were associated with EPTB. ESRD was associated with the most clinical presentations of EPTB other than meningeal and genitourinary TB. Patients age ≥45 years had a disproportionately high rate of bone TB, while foreign-born patients had increased pleural TB and HIV+ patients had increased meningeal TB. Age ≥45 years, HIV+ status, excessive alcohol use within the past 12 months, ESRD, and abnormal chest radiographs were independent risk factors for EPTB mortality during TB treatment. The epidemiologic risk factors identified by multivariate analyses provide new information that may be useful to health professionals in managing patients with EPTB.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), especially with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection, is a leading cause of death worldwide1. Individuals infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) may either be asymptomatic (latent TB infection, LTBI) or develop active TB disease2. For active TB disease, a small subset of patients (19.3–39.3%) present with either primary extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) or EPTB concurrent with pulmonary involvement, while the majority of patients develop pulmonary TB (PTB)3, 4. Some studies have suggested that the proportion of EPTB among all TB cases has been increasing in the United States (USA) (21% in 2013 compared to 16% in 1993) mainly because of the increasing prevalence of HIV infection5, 6.

Typically, Mtb infection leads to spatial and temporal lesion dynamics not only within a single individual but also between individuals7, 8. The most common extrapulmonary sites of TB infection are the lymph nodes, the pleura, the genitourinary system, the gastrointestinal tract, the bones, and the central nervous system. To date, the mechanisms for extrapulmonary dissemination remain largely unknown2. It has been found that host–pathogen interactions such as pathogen-associated molecular pattern signaling, antigen presentation, and immune recognition may be used by Mtb to mediate latency induction and pathogen reactivation2. These factors are believed to be important in establishing the site of disease presentation and dissemination. One recent study, which assessed within-host bacterial population dynamics in a macaque TB model by using a genome barcoding system coupled with serial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose radiotracers and positron emission tomography co-registered with computed tomography (PET/CT), suggested that in the first 6 weeks after infection, granuloma size but not bacterial burden is correlated with risk of local dissemination (<10 mm away) in the lungs9. Furthermore, genomic analyses of samples from lung and extrapulmonary biopsies of HIV-co-infected patients have demonstrated that the dissemination of Mtb from the lungs to extrapulmonary sites may occur as frequently as between lung sites10. Importantly, Mtb sub-lineages were differentially distributed throughout the lungs of these immunocompromised patients. Therefore, data from Lieberman and co-workers10 suggest that biopsies from the upper airway represent only a small fraction of the population diversity. These data are also consistent with a nonhuman-primate-model study which showed barcodes recovered from gastric and bronchoalveolar lavage samples represented only a fraction (3.75%) of all bacterial barcodes9. Additionally, there has been a study evaluating the immune response profile of inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-β in HIV-negative children with TB disease11. At the time of TB diagnosis, the immune response in all pediatric TB patients (suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased regulatory T cell frequency) was not significantly different between PTB and EPTB patients. However, the recovery of the immune response was observed in children with PTB but not in children with EPTB after 6 months of TB treatment11. These findings suggest that the host immune response following treatment is specific to the disease (PTB vs. EPTB) rather than due to the within-host defense and cannot explain why one individual develops PTB while another develops EPTB.

Clinically, EPTB is still underrecognized, and diagnoses are often delayed due to its paucibacillary nature and atypical presentations. In fact, many characteristics such as HIV and female gender have been recognized as risk factors for EPTB dissemination12–14. However, there are few population-based studies in the USA investigating the association between primary sites of Mtb infection and mortality during TB treatment. For instance, one study analyzed the epidemiology and risk factors of EPTB from 1993 through 2006 but did not analyze risk factors for patient mortality5. Another study demonstrated risk factors for EPTB and mortality at 6 months after TB diagnosis from 1995 through 1999 in Harris Country, Texas, but this study analyzed data at the county level and not at the state or country level15. The third example is the association of Mtb lineage with the site of TB disease in a study that analyzed US data from 2004 through 2008; the study reported that the Euro-American, Indo-Oceanic, and East African-Indian bacterial lineages were found exclusively in EPTB12. Given the variety of organ-specific clinical scenarios and the nonspecific systemic symptoms of EPTB, a more profound understanding of the site distribution of EPTB, as well as the risk factors associated with extrapulmonary dissemination and mortality, is important for developing suitable protocols to manage EPTB patients. Accordingly, this analysis aimed to determine the characteristics associated with EPTB dissemination and mortality during TB treatment by using recent epidemiological data from Texas.

Materials and methods

De-identified surveillance data of all confirmed TB patients reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s TB Genotyping Information Management System (TBGMIS) between January 2009 and December 2015 from the state of Texas, USA, were analyzed. TB disease was classified as exclusively PTB, exclusively EPTB or EPTB with concurrent PTB involvement. Sites of EPTB include pleural, lymphatic, bone, genitourinary, peritoneal, and meningeal locations, among others. All patients received anti-TB treatment, and their outcomes were recorded as “completed”, “died”, or “unknown”.

Cases were categorized by site of disease. Differences across groups (exclusively PTB, exclusively EPTB and EPTB with concurrent PTB involvement) were determined by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Logistic regression was used to determine the characteristics that were associated with patients having exclusively PTB compared to individuals identified to have (1) exclusively EPTB, (2) EPTB with concurrent PTB involvement, or (3) any EPTB (patients with exclusively EPTB and EPTB with concurrent PTB involvement). Odds ratios (OR), adjusted odds ratios (aOR), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. Multiple logistic regression modeling was also used to determine the risk of patient mortality during treatment in patients with exclusively EPTB. Analyses were performed with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Stata MP14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population and characteristics

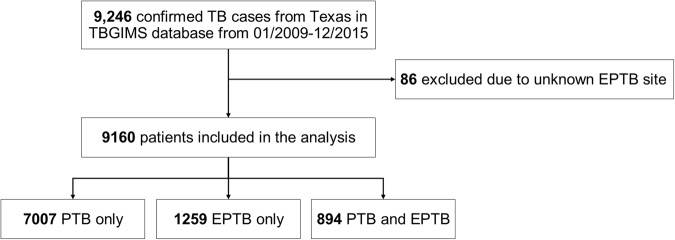

From 2009 to 2015, there were 9246 confirmed TB patients in Texas recorded in the TBGIMS database. After excluding 86 patients because their EPTB site was unknown, we included 9160 TB patients in the analysis (Fig. 1). The patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of exclusively EPTB patients were male (55.4%) and foreign born (59.1%). The proportions of patients age 25–44 years (39.6%) and Hispanic patients (46.6%) with exclusively EPTB were higher than the proportions of other age or ethnic groups with exclusively EPTB. The percentage of TB contact history was higher in patients with exclusively EPTB (3.7%) than in patients with PTB (9.0%) or EPTB with concurrent PTB (6.9%). In patients with exclusively EPTB, 448/1259 (35.6%) had abnormal chest radiographs and 17/1259 (1.4%) had culture-positive specimens. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) was identified in 0.4% of exclusively EPTB cases, 0.1% of EPTB cases with concurrent PTB, and 0.8% of exclusive PTB cases. Two extensively drug-resistant cases were identified in PTB patients. The most prevalent Mtb lineages of exclusively EPTB were Euro-American L4, East Asian L2, and Indo-Oceanic L1.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of the study population.

TBGIMS Genotyping Information Management System, PTB pulmonary TB, EPTB extrapulmonary TB

Table 1.

Characteristics of tuberculosis patients with pulmonary and extrapulmonary locations in Texas, USA, 2009–2015

| Variable | Total | Exclusively PTB | Exclusively EPTB | EPTB with PTB | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 9160 | 7007 | 1259 | 894 | |

| Age (years) | <0.01 | ||||

| 0–4 | 395 (4.3) | 297 (4.2) | 63 (5.0) | 35 (3.9) | |

| 5–14 | 213 (2.3) | 146 (2.1) | 43 (3.4) | 24 (2.7) | |

| 15–24 | 1048 (11.4) | 808 (11.5) | 129 (10.2) | 111 (12.4) | |

| 25–44 | 3054 (33.3) | 2245 (32.1) | 498 (39.6) | 311 (34.8) | |

| 45–64 | 3015 (33.0) | 2403 (34.3) | 361 (28.7) | 251 (28.1) | |

| ≥65 | 1435 (15.7) | 1108 (15.8) | 165 (13.1) | 162 (18.1) | |

| Gender | <0.01 | ||||

| Male | 5954 (65.0) | 4684 (66.8) | 697 (55.4) | 573 (64.1) | |

| Female | 3206 (35.0) | 2323 (33.2) | 562 (45.6) | 321 (35.9) | |

| Ethnicity | <0.01 | ||||

| White | 1103 (12.0) | 911 (13.0) | 108 (8.6) | 84 (9.4) | |

| Black | 1717 (18.7) | 1254 (17.9) | 262 (20.8) | 201 (22.5) | |

| Asian | 1517 (16.6) | 1052 (15.0) | 297 (23.6) | 168 (18.8) | |

| Hispanic | 4771 (52.1) | 3752 (53.6) | 587 (46.6) | 432 (48.3) | |

| Other | 52 (0.6) | 38 (0.5) | 5 (0.4) | 9 (1.0) | |

| HIV status | <0.01 | ||||

| Negative | 7128 (77.8) | 5518 (78.7) | 959 (76.2) | 651 (72.9) | |

| Positive | 608 (6.7) | 409 (5.9) | 77 (6.1) | 122 (13.6) | |

| Not offered | 1424 (15.5) | 1080 (15.4) | 223 (17.7) | 121 (13.5) | |

| Homeless | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 8682 (94.8) | 6600 (94.2) | 1229 (97.6) | 853 (95.4) | |

| Yes | 478 (5.2) | 407 (5.8) | 30 (2.4) | 41 (4.6) | |

| History of TB contacta | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 8417 (91.9) | 6373 (91.0) | 1212 (96.3) | 832 (93.1) | |

| Yes | 743 (8.1) | 634 (9.0) | 47 (3.7) | 62 (6.9) | |

| Excessive alcoholb | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 7494 (81.8) | 5633 (80.4) | 1138 (90.4) | 723 (80.9) | |

| Yes | 1666 (18.2) | 1374 (19.6) | 121 (9.6) | 171 (19.1) | |

| Injecting drug use | 0.03 | ||||

| No | 8930 (97.5) | 6819 (97.3) | 1241 (98.6) | 870 (97.3) | |

| Yes | 230 (2.5) | 188 (2.7) | 18 (1.4) | 24 (2.7) | |

| Non-injecting drug use | |||||

| No | 8263 (90.2) | 6257 (89.3) | 1202 (95.5) | 804 (89.9) | <0.01 |

| Yes | 897 (9.8) | 750 (10.7) | 57 (4.5) | 90 (10.1) | |

| Origin | 0.01 | ||||

| US born | 4108 (44.8) | 3188 (45.5) | 515 (40.9) | 405 (45.3) | |

| Foreign born | 5052 (55.2) | 3819 (54.5) | 744 (59.1) | 489 (54.7) | |

| Diabetes | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 7800 (85.2) | 5883 (84.0) | 1122 (89.1) | 795 (88.9) | |

| Yes | 1360 (14.8) | 1124 (16.0) | 137 (10.9) | 99 (11.1) | |

| End-stage renal disease | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 9024 (98.5) | 6935 (99.0) | 1230 (97.7) | 859 (96.1) | |

| Yes | 136 (1.5) | 72 (1.0) | 29 (2.3) | 35 (3.9) | |

| Immunosuppression | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 8936 (97.6) | 6854 (97.8) | 1217 (96.7) | 865 (96.8) | |

| Yes | 224 (2.4) | 153 (2.2) | 42 (3.3) | 29 (3.2) | |

| Previous TB | 0.08 | ||||

| No | 8819 (96.3) | 6733 (96.1) | 1226 (97.4) | 860 (96.2) | |

| Yes | 341 (3.7) | 274 (3.9) | 33 (2.6) | 34 (3.8) | |

| Inmate of a correctional facility | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 8210 (89.6) | 6161 (87.9) | 1192 (94.7) | 857 (95.9) | |

| Yes | 950 (10.4) | 846 (2.1) | 67 (5.3) | 37 (4.1) | |

| Resident of long-term care facility | 0.56 | ||||

| No | 9046 (98.8) | 6921 (98.8) | 1240 (98.5) | 885 (99.0) | |

| Yes | 114 (1.2) | 86 (1.2) | 19 (1.5) | 9 (1.0) | |

| Specimen smear | <0.01 | ||||

| Negative | 4097 (44.7) | 2832 (40.4) | 707 (56.2) | 558 (62.4) | |

| Positive | 3585 (39.1) | 3423 (48.9) | 5 (0.4) | 157 (17.6) | |

| Not done/Unknown | 1478 (16.1) | 752 (10.7) | 547 (43.4) | 179 (20.0) | |

| Specimen culture | <0.01 | ||||

| Negative | 2449 (26.7) | 1462 (20.9) | 669 (53.1) | 318 (35.6) | |

| Positive | 5185 (56.6) | 4782 (68.2) | 17 (1.4) | 386 (43.2) | |

| Not done/Unknown | 1526 (16.7) | 763 (10.9) | 573 (45.5) | 190 (21.3) | |

| Chest radiography | <0.01 | ||||

| Abnormal | 7694 (84.0) | 6485 (92.6) | 448 (35.6) | 761 (85.1) | |

| Normal | 1024 (11.2) | 233 (3.3) | 700 (55.6) | 91 (10.2) | |

| Not done/Unknown | 442 (4.8) | 289 (4.1) | 111 (8.8) | 42 (4.7) | |

| Radiographic cavity | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 5140 (56.1) | 4031 (57.5) | 437 (34.7) | 672 (75.2) | |

| Yes | 2540 (27.7) | 2441 (34.8) | 11 (0.9) | 88 (9.8) | |

| Unknown | 1480 (16.2) | 535 (7.7) | 811 (64.4) | 134 (15.0) | |

| DST profile | 0.11 | ||||

| None to RIF/INH | 6183 (67.5) | 4902 (70.0) | 684 (54.3) | 597 (66.8) | |

| RIF or INH | 512 (5.6) | 420 (6.0) | 44 (3.5) | 48 (5.4) | |

| MDR | 69 (0.7) | 63 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | |

| XDR | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unavailable | 2394 (26.1) | 1620 (23.1) | 526 (41.8) | 248 (27.7) | |

| Global Mtb Lineage | <0.01 | ||||

| Indo-Oceanic L1 | 634 (6.9) | 483 (6.9) | 93 (7.4) | 58 (6.5) | |

| East Asian L2 | 1121 (12.2) | 918 (13.1) | 98 (7.8) | 105 (11.7) | |

| East African-Indian L3 | 174 (1.9) | 115 (1.6) | 37 (2.9) | 22 (2.5) | |

| Euro-American L4 | 4344 (47.4) | 3569 (50.9) | 376 (29.9) | 399 (44.6) | |

| M. bovis | 105 (1.1) | 52 (0.8) | 36 (2.9) | 17 (1.9) | |

| Other | 28 (0.3) | 12 (0.2) | 8 (0.6) | 8 (0.9) | |

| Unknown | 2754 (30.2) | 1858 (26.5) | 611 (48.5) | 285 (31.9) | |

| Death at time of diagnosis | 0.04 | ||||

| No | 8964 (97.9) | 6870 (98.0) | 1220 (96.9) | 874 (97.8) | |

| Yes | 196 (2.1) | 137 (2.0) | 39 (3.1) | 20 (2.2) | |

| Death during TB treatment | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 8610 (94.0) | 6592 (94.1) | 1209 (96.0) | 809 (90.5) | |

| Yes | 551 (6.0) | 416 (5.9) | 50 (4.0) | 85 (9.5) | |

PTB pulmonary tuberculosis, EPTB extrapulmonary tuberculosis, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, RIF rifampin, INH isoniazid, MDR multidrug resistant, XDR extensively drug resistant. Differences across groups were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate

aPatients with a history of contact with a known TB index case within 2 years

bExcessive alcohol use within the past 12 months

Sites of EPTB

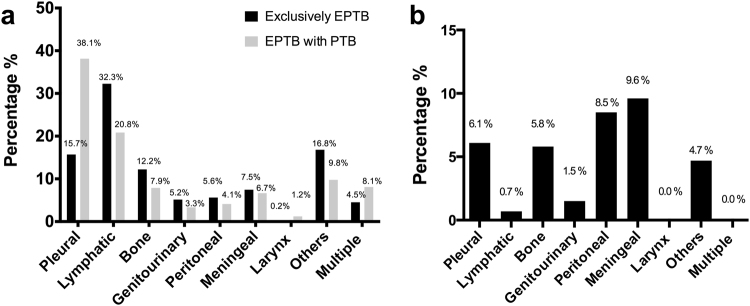

The distribution of EPTB sites is shown in Fig. 2a. Of the patients with exclusively EPTB, the most common sites of TB disease included pleural (15.7%), lymphatic (32.3%), bone (12.2%), and meningeal (7.5%) sites. The most common sites of TB disease in patients having EPTB with concomitant PTB were also pleural (38.1%), lymphatic (20.8%), bone (7.9%), and meningeal (6.7%) areas.

Fig. 2. Distribution of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by site and associated mortality.

a Distribution of extrapulmonary sites in patients with concurrent pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) or exclusively extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB). b Mortality distribution by extrapulmonary sites in patients with exclusively EPTB

Risk factors for EPTB and its specific sites

Multivariable analyses were performed in order to identify associations between sociodemographic, microbiologic, and clinical characteristics of EPTB patients and sites of EPTB. Female patients (aOR 1.32, 95% CI 1.19–1.46), as well as patients with HIV+ status (aOR 1.77, 95% CI 1.47–2.13), immunosuppression (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.00–1.77), and ESRD (aOR 3.42, 95% CI 2.39–4.88) were at a significantly elevated risk of EPTB (Table 2). Patients with a history of contact with a known TB index case within 2 years (aOR 0.44, 95% CI 0.35–0.55) and those with diabetes (aOR 0.61, 95% CI 0.52–0.71) were less likely to have EPTB than PTB (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses of patients’ characteristics with extrapulmonary tuberculosis in Texas, USA, 2009–2015

| Characteristics | Exclusively EPTB vs. exclusively PTB | EPTB with PTB vs. exclusively PTB | Any EPTB vs. exclusively PTB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) |

| 5–14 | 1.42 (1.04–1.96) | 1.19 (0.85–1.68) | 0.81 (0.55–1.19) | 0.96 (0.62–1.49) | 1.12 (0.86–1.50) | 0.97 (0.74–1.28) |

| 15–24 | 1.98 (1.356–2.88) | 2.33 (1.56–3.46) | 1.12 (0.71–1.79) | 1.23 (0.76–1.99) | 1.56 (1.14–2.13) | 1.33 (0.96–1.84) |

| 25–44 | 1.07 (0.837–1.37) | 1.10 (0.85–1.42) | 0.90 (0.73–1.22) | 0.93 (0.71–1.21) | 1.01 (0.83–1.22) | 0.97 (0.80–1.18) |

| 45–64 | 1.49 (1.232–1.80) | 1.57 (1.29–1.91) | 0.95 (0.77–1.16) | 0.80 (0.67–1.03) | 1.22 (1.05–1.42) | 1.13 (0.72–1.32) |

| ≥65 | 1.01 (0.828–1.23) | 1.22 (0.99–1.49) | 0.71 (0.58–0.88) | 0.67 (0.54–0.83) | 0.86 (0.74–1.01) | 1.06 (0.91–1.24) |

| Gender (female) | 1.36 (1.20–1.54) | 1.42 (1.26–1.62) | 1.12 (0.96–1.30) | 1.16 (1.00–1.36) | 1.41 (1.27–1.55) | 1.32 (1.19–1.46) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) |

| Black | 0.84 (0.33–2.15) | 0.92 (0.35–2.38) | 0.39 (0.18–0.83) | 0.37 (0.17–0.80) | 0.57 (0.30–1.08) | 0.53 (0.28–1.01) |

| Asian | 0.76 (0.61–0.94) | 0.80 (0.63–1.02) | 0.68 (0.32–1.42) | 0.57 (0.17–1.20) | 1.00 (0.54–1.87) | 0.87 (0.46–1.63) |

| Hispanic | 1.34 (1.14–1.57) | 1.34 (1.12–1.60) | 0.67 (0.32–1.42) | 0.67 (0.31–1.45) | 1.20 (0.64–2.24) | 1.03 (0.54–1.95) |

| Other | 1.81 (1.55–2.11) | 1.57 (1.34–1.85) | 0.49 (0.23–1.01) | 0.48 (0.23–1.02) | 0.74 (0.40–1.37) | 0.68 (0.37–1.28) |

| Homeless | 0.56 (0.38–0.83) | 0.57 (0.40–0.84) | 0.78 (0.56–1.08) | 0.70 (0.50–1.00) | 0.55 (0.43–0.72) | 0.65 (0.49–0.85) |

| History of TB contacta | 0.39 (0.29–0.53) | 0.28 (0.21–0.39) | 0.75 (0.57–0.98) | 0.71 (0.53–0.96) | 0.54 (0.44–0.66) | 0.44 (0.35–0.55) |

| Excessive alcoholb | 0.61 (0.49–0.75) | 0.60 (0.48–0.74) | 1.12 (0.91–1.38) | 1.03 (0.84–1.26) | 0.64 (0.56–0.74) | 0.78 (0.67–0.91) |

| Injecting drug use | 1.08 (0.64–1.82) | 1.04 (0.62–1.76) | 1.00 (0.63–1.60) | 0.96 (0.60–1.53) | 0.72 (0.52–1.01) | 1.01 (0.70–1.46) |

| Non-injecting drug use | 0.53 (0.39–0.72) | 0.52 (0.40–0.71) | 0.87 (0.67–1.14) | 0.85 (0.65–1.11) | 0.61 (0.51–0.74) | 0.68 (0.55–0.84) |

| Diabetes | 0.63 (0.51–0.77) | 0.61 (0.50–0.74) | 0.65 (0.51–0.82) | 0.61 (0.49–0.77) | 0.64 (0.56–0.75) | 0.61 (0.52–0.71) |

| HIVc | 1.14 (0.87–1.49) | 1.20 (0.92–1.55) | 2.65 (2.10–3.35) | 2.57 (2.05–3.21) | 1.64 (1.38–1.96) | 1.77 (1.47–2.13) |

| Immunosuppression | 1.44 (0.10–2.07) | 1.36 (0.95–1.95) | 1.20 (0.78–1.83) | 1.15 (0.75–1.76) | 1.53 (1.15–2.03) | 1.31 (1.00–1.77) |

| ESRD | 2.51 (1.58–3.99) | 2.59 (1.63–4.17) | 4.30 (2.78–6.64) | 4.45 (2.88–6.86) | 3.32 (2.33–4.75) | 3.42 (2.39–4.88) |

| Foreign born | 1.04 (0.89–1.22) | 0.92 (0.80–1.06) | 1.06 (0.89–1.28) | 0.99 (0.85–1.17) | 1.05 (0.93–1.20) | 0.95 (0.85–1.06) |

| Previous TB | 0.68 (0.47–1.00) | 0.69 (0.47–1.01) | 0.99 (0.68–1.43) | 0.95 (0.66–1.38) | 0.81 (0.61–1.07) | 0.80 (0.61–1.06) |

EPTB extrapulmonary tuberculosis, PTB pulmonary tuberculosis, OR odds ratio, aOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, ESRD end-stage renal disease, TB, tuberculosis

aPatients with a history of contact with a known TB index case within 2 years

bExcessive alcohol use within the past 12 months

cHIV unknown categorized as negative

Significant odds ratios (p<0.005) are in bold

ESRD was associated with most subtypes of EPTB, excluding meningeal and genitourinary TB (Table 3). Patients age ≥45 years had a disproportionately high rate of bone TB (aOR 1.47, 95% CI 1.04–2.08), while foreign-born patients had more pleural TB (aOR 1.77, 95% CI 1.31–2.41) and HIV+ patients had more meningeal TB (aOR 5.73, 95% CI 3.43–9.56) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk factors associated with subsites of exclusively extrapulmonary tuberculosis compared to pulmonary tuberculosis in Texas, USA, 2009–2015

| Characteristics | Pleural (n = 198) | Lymphatic (n = 407) | Bone (n = 154) | Genitourinary (n = 65) | Peritoneal (n = 71) | Meningeal (n = 94) | Others (n = 212) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Age (≥45 years) | 1.04 (0.76–1.40) | 0.56 (0.44–0.71) | 1.47 (1.04–2.08) | 1.00 (0.60–1.68) | 1.06 (0.64–1.74) | 0.75 (0.48–1.17) | 1.06 (0.79–1.42) |

| Gender (female) | 0.91 (0.67–1.25) | 2.04 (1.66–2.51) | 0.69 (0.48–0.99) | 1.44 (0.87–2.40) | 1.96 (1.20–3.21) | 1.22 (0.79–1.88) | 1.39 (1.05–1.86) |

| Ethnicity (White) | 0.73 (0.46–1.14) | 0.47 (0.29–0.77) | 1.14 (0.69–1.88) | 1.26 (0.50–3.22) | 0.62 (0.23–1.63) | 0.82 (0.39–1.72) | 0.77 (0.45–1.30) |

| Homeless | 0.90 (0.48–1.68) | 0.29 (0.09–0.92) | 0.54 (0.19–1.50) | 0.47 (0.06–3.57) | 0.69 (0.16–2.95) | 0.38 (0.09–1.63) | 0.72 (0.29–1.82) |

| Excessive alcohola | 1.17 (0.80–1.71) | 0.38 (0.23–0.63) | 0.42 (0.23–0.75) | 0.82 (0.35–1.90) | 1.50 (0.77–2.95) | 0.54 (0.26–1.14) | 0.30 (0.16–0.57) |

| Injecting drug use | 0.91 (0.35–2.34) | 0.63 (0.15–2.68) | 0.87 (0.20–3.79) | 5.26 (1.10–25.36) | 0.80 (0.10–6.36) | 2.20 (0.60–8.05) | 0.84 (0.20–3.62) |

| Non-injecting drug use | 0.82 (0.49–1.38) | 0.37 (0.18–0.74) | 0.70 (0.33–1.53) | 0.12 (0.02–1.05) | 0.58 (0.19–1.76) | 0.39 (0.14–1.07) | 0.58 (0.27–1.24) |

| Diabetes | 0.68 (0.43–1.07) | 0.35 (0.23–0.54) | 0.92 (0.60–1.42) | 0.54 (0.24–1.22) | 0.71 (0.35–1.44) | 0.51 (0.23–1.13) | 0.84 (0.56–1.26) |

| HIVb | 0.62 (0.30–1.28) | 1.20 (0.74–1.95) | 0.54 (0.19–1.50) | 0.64 (0.15–2.66) | 1.13 (0.40–3.17) | 5.73 (3.43–9.56) | 1.52 (0.86–2.68) |

| Immunosuppression | 0.80 (0.28–2.23) | 0.88 (0.41–1.90) | 2.54 (1.30–4.97) | 1.57 (0.36–6.78) | 2.29 (0.77–6.85) | 1.79 (0.62–5.12) | 0.95 (0.38–2.38) |

| ESRD | 2.74 (1.06–7.10) | 2.96 (1.28–6.87) | 4.05 (1.82–8.98) | 1.72 (0.22–13.32) | 3.56 (1.01–12.56) | – | 1.40 (0.43–4.61) |

| Foreign born | 1.77 (1.31–2.41) | 0.88 (0.71–1.10) | 0.98 (0.68–1.40) | 0.37 (0.19–0.70) | 0.70 (0.41–1.18) | 0.97 (0.62–1.51) | 0.84 (0.62–1.14) |

| Previous TB | 0.27 (0.07–1.10) | 0.80 (0.43–1.49) | 1.37 (0.63–2.98) | 1.20 (0.37–3.89) | 0.37 (0.05–2.70) | 0.76 (0.24–2.43) | 0.52 (0.20–1.43) |

aOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, ESRD end-stage renal disease

Analysis excluded subjects with multiple subsite involvement (n = 57) and laryngeal sites (n = 3)

aExcessive alcohol use within the past 12 months

bHIV unknown categorized as negative

Significant odds ratios (p<0.005) are in bold

Risk factors for mortality during treatment in patients with exclusively EPTB

Among the 1111 patients with exclusively EPTB who had mortality-related data available, 50 (4.5%) died during anti-TB treatment. Mortality was highest among those patients presenting with meningeal (9.6%) or peritoneal TB (8.5%) and lower among those individuals with lymphatic TB (0.7%) (Fig. 2b). During treatment, no mortality was reported among patients having either laryngeal or multisite TB. Age ≥45 (aOR 3.75, 95% CI 1.71–8.22), HIV+ status (aOR 4.70, 95% CI 1.54–14.32), excessive alcohol use within the past 12 months (aOR 3.34, 95% CI 1.45–7.67), ESRD (aOR 4.45, 95% CI 1.38–14.33), and abnormal chest radiographs (aOR 2.18, 95% CI 1.09–4.35) were risk factors for TB mortality with adjusted odds ratio (Table 4).

Table 4.

Risk factors for mortality during anti-tuberculosis treatment in patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis in Texas, USA, 2009–2015

| Variable | Treatment completed (n = 1061) | Died during treatment (n = 50) | Mortality risk (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 0–14 | 105 (9.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | – | ||

| 15–24 | 116 (10.9%) | 2 (4.0%) | 1.7% | (reference) | ||

| 25–44 | 438 (41.3%) | 9 (18.0%) | 2.0% | 1.19 (0.25, 5.59) | ||

| 45–64 | 292 (27.5%) | 17 (34.0%) | 5.5% | 3.38 (0.77, 14.85) | ||

| ≥65 | 110 (10.4%) | 22 (44.0%) | 16.7% | 11.60 (2.66, 50.49) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <45 | 659 (62.1%) | 11 (22.0%) | 1.6% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| ≥45 | 402 (37.9%) | 39 (78.0%) | 8.8% | 5.81 (2.94, 11.48) | 3.75 (1.71, 8.22) | 0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 491 (46.3%) | 20 (40.0%) | 3.9% | (reference) | ||

| Male | 570 (53.7%) | 30 (60.0%) | 5.0% | 1.29 (0.72, 2.30) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 84 (7.9%) | 9 (18.0%) | 9.7% | (reference) | ||

| Black | 209 (19.7%) | 11 (22.0%) | 5.0% | 0.49 (0.20, 1.23) | ||

| Hispanic | 501 (47.2%) | 24 (48.0%) | 4.6% | 0.45 (0.20, 1.00) | ||

| Asian | 262 (24.7%) | 6 (12.0%) | 2.2% | 0.21 (0.07, 0.62) | ||

| Other | 5 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | 1.00 (0.00, 0.00) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Non-White | 977 (92.1%) | 41 (82.0%) | 4.0% | (reference) | ||

| White | 84 (7.9%) | 9 (18.0%) | 9.7% | 2.55 (1.20, 5.43) | ||

| HIV status | ||||||

| Negative | 847 (79.8%) | 21 (42.0%) | 2.4% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| Positive | 53 (5.0%) | 6 (12.0%) | 10.2% | 4.57 (1.77, 11.79) | 4.70 (1.54, 14.32) | 0.01 |

| Unknown | 161 (15.2%) | 23 (46.0%) | 12.5% | 5.76 (3.11, 10.66) | 6.55 (3.19, 13.44) | <0.001 |

| Homeless | ||||||

| No | 1040 (98.0%) | 46 (92.0%) | 4.2% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| Yes | 21 (2.0%) | 4 (8.0%) | 16.0% | 4.31 (1.42, 13.06) | 1.57 (0.40, 6.17) | 0.52 |

| Excessive alcohol use | ||||||

| No | 973 (91.7%) | 37 (74.0%) | 3.7% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| Yes | 88 (8.3%) | 13 (26.0%) | 12.9% | 3.88 (1.99, 7.58) | 3.34 (1.45, 7.67) | 0.01 |

| Injecting drug use | ||||||

| No | 1050 (99.0%) | 48 (96.0%) | 4.4% | (reference) | ||

| Yes | 11 (1.0%) | 2 (4.0%) | 15.4% | 3.98 (0.86, 18.44) | ||

| Foreign born | ||||||

| No | 415 (39.1%) | 29 (58.0%) | 6.5% | (reference) | ||

| Yes | 646 (60.9%) | 21 (42.0%) | 3.1% | 0.47 (0.26, 0.83) | ||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | 948 (89.3%) | 40 (80.0%) | 4.0% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| Yes | 113 (10.7%) | 10 (20.0%) | 8.1% | 2.10 (1.02, 4.31) | 1.55 (0.65, 3.69) | 0.32 |

| End-stage renal disease | ||||||

| No | 1043 (98.3%) | 44 (88.0%) | 4.0% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| Yes | 18 (1.7%) | 6 (12.0%) | 25.0% | 7.90 (2.99, 20.88) | 4.45 (1.38, 14.33) | 0.01 |

| Immunosuppression (medical condition or medication) | ||||||

| No | 1027 (96.8%) | 44 (88.0%) | 4.1% | |||

| Yes | 34 (3.2%) | 6 (12.0%) | 15.0% | 4.12 (1.64, 10.32) | ||

| Previous TB | ||||||

| No | 1033 (97.4%) | 50 (100.0%) | 4.6% | – | ||

| Yes | 28 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | |||

| Inmate of a correctional facility | ||||||

| No | 967 (94.8%) | 48 (98.0%) | 4.7% | (reference) | ||

| Yes | 53 (5.2%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1.9% | 0.38 (0.05, 2.81) | ||

| Resident of long-term care facility | ||||||

| No | 1048 (98.8%) | 47 (94.0%) | 4.3% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| Yes | 13 (1.2%) | 3 (6.0%) | 18.8% | 5.15 (1.42, 18.67) | 2.15 (0.50, 9.26) | 0.31 |

| AFB smear | ||||||

| Negative | 627 (99.4%) | 17 (94.4%) | 2.6% | (reference) | ||

| Positive | 4 (0.6%) | 1 (5.6%) | 20.0% | 9.22 (0.98, 86.93) | ||

| Culture | ||||||

| Negative | 602 (97.6%) | 12 (92.3%) | 2.0% | (reference) | ||

| Positive | 15 (2.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | 6.3% | 3.34 (0.41, 27.40) | ||

| TB-CXR | ||||||

| No | 611 (62.8%) | 15 (33.3%) | 2.4% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| Yes | 362 (37.2%) | 30 (66.7%) | 7.7% | 3.38 (1.79, 6.36) | 2.18 (1.09, 4.35) | 0.03 |

| Cavitation on CXR | ||||||

| No | 354 (97.8%) | 30 (100.0%) | 7.8% | – | ||

| Yes | 8 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | |||

| DST profile | ||||||

| Sensitive to RIF and INH | 560 (52.8%) | 40 (80.0%) | 6.7% | |||

| Resistant to RIF or INH | 39 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | |||

| MDR-TB | 3 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | (reference) | ||

| Unavailable | 459 (43.3%) | 10 (20.0%) | 2.1% | 0.31 (0.15, 0.62) | ||

| Genotyping lineage | ||||||

| Indo-Oceanic (L1) | 80 (7.5%) | 4 (8.0%) | 4.8% | 0.79 (0.20, 3.05) | ||

| East Asian (L2) | 79 (7.4%) | 5 (10.0%) | 6.0% | (reference) | ||

| East African-Indian (L3) | 35 (3.3%) | 1 (2.0%) | 2.8% | 0.45 (0.05, 4.01) | ||

| Euro-American (L4) | 300 (28.3%) | 27 (54.0%) | 8.3% | 1.42 (0.53, 3.81) | ||

| M. bovis | 27 (2.5%) | 3 (6.0%) | 10.0% | 1.76 (0.39, 7.84) | ||

| Other | 8 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | 1.00 (0.00, 0.00) | ||

| Unknown | 532 (50.1%) | 10 (20.0%) | 1.8% | 0.30 (0.10, 0.89) | ||

| Genotyping lineage | ||||||

| Not East Asian | 354 (97.8%) | 30 (100.0%) | 7.8% | (reference) | (reference) | |

| East Asian (L2) | 8 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | 1.38 (0.53, 3.58) | 1.58 (0.53, 4.74) | 0.42 |

TB tuberculosis, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, TB-CXR tuberculosis chest X-ray, DST drug susceptibility test, RIF rifampin, INH isoniazid, MDR-TB multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, OR odds ratios

Analysis was performed on 1111 patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis only and having treatment outcome information available

Discussion

Although risk factors for the development of exclusively EPTB compared to PTB have been described in several studies5, 12, 16, 17, there are still inconsistent findings among studies from different regions, including substantial state-level heterogeneity in the reported epidemiological data18. We performed an analysis of EPTB patients in the state of Texas. We found that patients who were age ≥45 years, female, HIV+, and suffering from ESRD were at a significantly elevated risk of EPTB. In particular, age ≥45 years, HIV+, excessive alcohol use within the past 12 months, ESRD, and abnormal chest radiographs were risk factors for EPTB mortality during treatment.

The observed demographics of female gender and foreign-born origin in the USA have been previously reported as risk factors for EPTB5, 12, 17, 19, 20. Similarly, we found that female gender and Hispanic ethnicity were associated with patients who presented with exclusively EPTB after adjusting for other confounding factors. We further noted that ethnicity was not associated with any specific site of EPTB and that female gender was associated with lymphatic and peritoneal TB.

The risk of TB development in the foreign-born population was substantially elevated even more than 5 years after entering the USA20. In our study population, more than half (55.2%) of the patients were born outside the USA. The cervical lymphatic site was found to be a more common disease site among foreign-born EPTB patients than among US-born patients in North Carolina21. However, a study at a single urban US public hospital did not show any risk between foreign birth with sites of EPTB13. From our results, foreign birth was associated with increased risk of pleural TB. Pleural TB is the second most common type of EPTB but the leading manifestation in settings with high TB22, 23. Given that TB disease among foreign-born populations is normally considered to result from the reactivation of LTBI24, one explanation might be that pleural TB was the primary manifestation of LTBI reactivation22. It is also possible that the association between foreign birth and pleural TB is due to the effect of BCG vaccination on foreign-born individuals. Studies have shown that pleuritis is induced by Mycobacterium bovis BCG, and the underlying mechanisms have been elucidated25. However, non-association of BCG status among patients with PTB, pleural TB, and other types of EPTB was seen in a study with a majority of BCG-vaccinated patients23. From the findings described herein, studies can be initiated to further evaluate the BCG status of foreign-born patients in relation to pleural TB.

Drug users and the elderly remain the groups at high risk of developing LTBI and TB disease19. The prevalence of illicit drug use has been previously shown to be higher in patients with PTB than in patients with EPTB15, 17. Similarly, the prevalence of injecting drug use and non-injecting drug use was also higher in patients with PTB than patients with exclusively EPTB in our study. We further observed that injecting drug use was associated with patients with genitourinary TB. In addition, non-injecting drug use as a non-risk factor for EPTB compared to PTB has been reported26. From our results, non-injecting drug use was also negatively associated with patients having exclusively EPTB or any EPTB compared to PTB. We demonstrated that the age groups 15–24 and 45–64 were associated with exclusively EPTB. Meanwhile, Click et al.12 indicated that age 0–4 was associated with exclusively EPTB. TB in elderly patients can involve almost any organ in the body27. We found that patients age >45 years were at an increased risk of bone TB but not with other extrapulmonary sites. This finding is consistent with a large-population-based study in Europe16. Additionally, ages <15 and >65 years were likely to be associated with the most comment types of EPTB15.

According to a 2016 CDC report, high rates of TB cases overall and TB cases attributable to extensive recent transmission were identified frequently among people experiencing homelessness within the past year and residents of a correctional facility at the time of diagnosis28. However, EPTB was more common in non-homeless patients than in the homeless, as previously reported5, 17. The number of homeless cases was significantly higher in PTB (5.8%) than in exclusively EPTB (2.4%) in our population. Furthermore, we showed that being homeless was negatively associated with EPTB and especially lymphatic TB. Neither the Magee study nor our study showed any significant differences in the proportion of residents of correctional facility patients with exclusively EPTB vs. PTB17. These findings suggest that Mtb infection is not site-specific in correctional facility patients.

It is well known that patients with HIV have an increased risk of EPTB13, 14. Click et al.12 found that HIV was associated with both exclusively EPTB and any EPTB. Moreover, the same study demonstrated that the association between individuals with HIV infection and extrapulmonary disease was greater for EPTB with concurrent pulmonary involvement than for exclusively EPTB alone. In our population, HIV was associated with EPTB with concurrent pulmonary involvement and any EPTB but not with exclusively EPTB. We further identified that HIV was associated with meningeal TB at more than five times the odds, while other sites were not found to be related. In addition, low CD4 lymphocyte counts in hospitalized patients with HIV-co-infected EPTB were found to be associated with meningeal TB and disseminated TB in a single hospital study in the USA13.

The prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) continues to rise by approximately 20,000 cases per year in the USA29. Consistent epidemiologic evidence has shown that this population is at risk for developing active TB30. ESRD as a risk factor for EPTB has also been reported in studies in Taiwan and the US state of Georgia17, 31. Accordingly, ESRD was associated with exclusively EPTB, EPTB with concurrent pulmonary involvement, and all cases of EPTB compared to PTB in our population-based analysis. We also found that ESRD was specifically associated with pleural, lymphatic, bone and peritoneal TB. Thus, patients with ESRD are at a high risk of progressing to EPTB. One possibility regarding the underlying mechanisms is that the persistence of impaired cell-mediated immunity in ESRD may leave these patients susceptible to Mtb infection or activation of latent infection32. This phenomenon has also been observed in organ transplantation receipts who receive post-transplant immunosuppressive medications that specifically target T cell-mediated immunity33, 34. In regard to the screening strategy among patients with chronic renal disease (CRD), both the American Thoracic Society35 and American Transplant Society36 guidelines recommend that all immunocompromised subjects and transplant candidates be screened for TB with a tuberculin skin test (TST) or IFN-γ releasing assay (IGRA). The WHO provides more specific guidance on screening all dialysis patients with TST or IGRAs37. Beyond the screening strategy, diagnosis of EPTB remains difficult because of the paucibacillary nature. Thus, it is necessary to advance knowledge about the association of CRD/ESRD and EPTB and strategies to improve the prevention, detection, and treatment of EPTB with ESRD.

Consistent with the current literature, our analyses showed that age ≥45 years, ESRD, HIV+ status, excessive alcohol use within the past 12 months, and abnormal chest radiography were significantly associated with mortality during anti-TB treatment in patients with exclusively EPTB17, 38. In the USA, excess alcohol use may represent a large portion of TB burden38. The relationship between excessive alcohol use and the development of TB disease as well as TB-associated morbidity and mortality has been presumed to be due to impaired immune function39. Other confounding factors such as older age, diabetes, ESRD, and HIV are all related to decreased immune function. HIV was highly associated with mortality during treatment in our analysis, which is consistent with other epidemiologic and observational studies with mortality ranging from 6% to 32%40. Another important finding of our study was that ESRD was associated with more than quadruple the odds of mortality during anti-TB treatment in patients having exclusively EPTB. Given these findings, we suggest that patients with decreased immune function or immunosuppression are at an increased risk of mortality during treatment and that host immune response may determine the difference in survival. Approaches to meet the objective of optimizing efficacy and safety of treatment, especially for TB-HIV co-infection as well as ESRD, to reduce mortality both in adults and children are urgently required. As shown in a prospective cohort study that enrolled hospitalized HIV co-infected patients with microbiologically confirmed drug-susceptible TB in South Africa, mortality within 12 weeks was positively associated with elevated concentrations of procalcitonin, activation of the innate immune system, and anti-inflammatory markers41. Procalcitonin, a product induced by TNF-α and IL-2 during a bacterial infection, has already shown its value in distinguishing TB from bacterial pneumonia and TB meningitis from bacterial meningitis42, 43. A higher level of serum procalcitonin was associated with a poorer prognosis in TB meningitis43. Moreover, serum procalcitonin has been reported as an appropriate indicator of infection in ESRD patients44. Therefore, identifying a correlation between the host’s immunologic phenotypes and the severity of disease or comorbidities, as well as treatment response, would enable the direct selection of host-directed therapeutics and a potentially beneficial and improved TB outcome.

Another important consideration for the risk of EPTB is diabetes status, as several studies have identified diabetes as a risk factor for developing active TB and poor treatment outcomes45. For instance, a study in the UK has reported that patients with diabetes had an increased risk of developing TB compared to a control group46. Among patients undergoing TB treatment, patients with diabetes had an increased mortality risk compared to those without diabetes47. However, compared to the control group, TB patients with diabetes had an increased probability of having PTB as opposed to EPTB46. Furthermore, both our study and a cohort study in the US state of Georgia found TB patients with diabetes to have an increased probability of EPTB as opposed to PTB, and diabetes was not associated with EPTB mortality during TB treatment17. In an additional study, diabetes did not contribute to TB-related death in adult patients in the USA48. Thus, the inconsistent findings encourage further investigations on the impact of diabetes in PTB and EPTB patients. It is worth emphasizing that the incidence of ESRD is higher in the diabetic population than in the non-diabetic population49. Since ESRD is an independent risk factor for EPTB as shown in our study, it may be necessary to account for the association between diabetes and ESRD as a co-epidemic, which would potentially account for the risk of EPTB as well as treatment outcomes.

Among available data for patients with exclusively EPTB, the most prevalent Mtb lineages were Euro-American L4, followed by East Asian L2 and Indo-Oceanic L1. This finding was consistent with a previous nationwide study in the USA12. Click et al.12 suggested that the percentage of cases with exclusively EPTB differs for the four lineages—East Asian, 13.0%; Euro-American, 13.8%; Indo-Oceanic, 22.6%; and East African-Indian, 34.3%—while EPTB with pulmonary involvement did not. However, Click’s study did not show data for M. bovis. Consistent with the results of previous studies50, 51, we found a higher proportion of M. bovis in patients with exclusively EPTB than in patients with exclusively PTB or EPTB with pulmonary involvement. Geographically, patients with M. bovis TB residing along the US–Mexico border had a disproportionately high incidence of M. bovis50. This may also be reflected in our results, as Texas is a US state bordering Mexico. The tradition of raw milk and cheese consumption, especially in Hispanic communities, may be another common reason for M. bovis infection52. Additionally, we found that positive smear and culture, direct susceptibility test profile and genotyping lineage were not risk factors for mortality from exclusively EPTB during TB treatment. These results may be limited due to many individuals with unknown Mtb status, either because the test was not performed or because the results were not recorded. Instead of bacterial factors, host risk factors such as HIV, age ≥45, excessive alcohol use, and abnormal chest X-ray findings were associated with mortality during treatment of EPTB in our study.

One important limitation of our study is the unavailability of data in some categories. Therefore, the reported crude and adjusted odds ratios could be biased due to unmeasured covariates or unknown confounders. State TB surveillance reporting does not include the depth of clinical information necessary to further investigate recognized risk factors in the epidemiology of EPTB (e.g., CD4 lymphocyte counts for HIV patients and smoking status). An observational design in a large cohort will be necessary to assess the true effect of these factors. Given that Texas has one of the highest TB prevalence rates of any US state and has a more diverse population than many other states, findings from our analysis may not apply to settings elsewhere in the country.

Conclusion

The present study characterized the important differences in the population-level dynamics of EPTB, as well as its specific sites, which included demographic factors and clinical characteristics in addition to the heterogeneities within sites of EPTB during the 7-year study period. Age ≥45 years, HIV+ status, and ESRD were identified as risk factors for both EPTB establishment and resulting mortality during treatment. Although the scientific question of the extrapulmonary dissemination remains to be answered, the study’s findings could allow us to design supportive treatments for specific subgroups of patients with increased mortality, such as those with a HIV+ status and those with compromised renal function, in order to improve their outcomes and ultimately minimize the transmission of TB.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Opening Project of Zhejiang Provincial Top Key Discipline of Clinical Medicine (LKFJ008 to X.Q.), the Key Science and Technology Innovation Team of Zhejiang (2010R50048 to J.L.), and Zhejiang Provincial Program for the Cultivation of High-level Innovative Health Talents and Key Laboratory of Laboratory Medicine, Ministry of Education, China.

Author contributions:

X.Q. and E.A.G designed the study. D.T.N collected the data. X.Q. and D.T.N. analyzed the data. X.Q., D.T.G., J.L., A.E.A., X.B., and E.A.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xu Qian, Duc T. Nguyen

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report (2016). http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- 2.Pai M, et al. Tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016;2:16076. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandgren A, Hollo V, van der Werf MJ. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the European Union and European Economic Area, 2002 to 2011. Eur. Surveill. 2013;18:20431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sama JN, et al. High proportion of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in a low prevalence setting: a retrospective cohort study. Public Health. 2016;138:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peto HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, LoBue PA, Armstrong LR. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1350–1357. doi: 10.1086/605559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/features/dstuberculosis

- 7.Lin PL, et al. Sterilization of granulomas is common in active and latent tuberculosis despite within-host variability in bacterial killing. Nat. Med. 2014;20:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nm.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Via LE, et al. Host-mediated bioactivation of pyrazinamide: implications for efficacy, resistance, and therapeutic alternatives. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015;1:203–214. doi: 10.1021/id500028m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin CJ, et al. Digitally barcoding Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals in vivo infection dynamics in the Macaque model of tuberculosis. mBio. 2017;8:e00312–e00317. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00312-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman TD, et al. Genomic diversity in autopsy samples reveals within-host dissemination of HIV-associated Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 2016;22:1470–1474. doi: 10.1038/nm.4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whittaker E, Nicol M, Zar HJ, Kampmann B. Regulatory T cells and pro-inflammatory responses predominate in children with tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:448. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Click ES, Moonan PK, Winston CA, Cowan LS, Oeltmann JE. Relationship between Mycobacterium tuberculosis phylogenetic lineage and clinical site of tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:211–219. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leeds IL, et al. Site of extrapulmonary tuberculosis is associated with HIV infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:75–81. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterling TR, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-seronegative adults with extrapulmonary tuberculosis have abnormal innate immune responses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;33:976–982. doi: 10.1086/322670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez OY, et al. Extra-pulmonary manifestations in a large metropolitan area with a low incidence of tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2003;7:1178–1185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sotgiu G, et al. Determinants of site of tuberculosis disease: an analysis of European surveillance data from 2003 to 2014. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0186499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magee MJ, Foote M, Ray SM, Gandhi NR, Kempker RR. Diabetes mellitus and extrapulmonary tuberculosis: site distribution and risk of mortality. Epidemiol. Infect. 2016;144:2209–2216. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816000364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shrestha S, Hill AN, Marks SM, Dowdy DW. Comparing drivers and dynamics of tuberculosis in California, Florida, New York, and Texas. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2017;196:1050–1059. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0377OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deiss RG, Rodwell TC, Garfein RS. Tuberculosis and illicit drug use: review and update. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48:72–82. doi: 10.1086/594126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cain KP, et al. Tuberculosis among foreign-born persons in the United States: achieving tuberculosis elimination. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2007;175:75–79. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kipp AM, Stout JE, Hamilton CD, Van Rie A. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, and foreign birth in North Carolina, 1993-2006. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeon D. Tuberculous pleurisy: an update. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. (Seoul) 2014;76:153–159. doi: 10.4046/trd.2014.76.4.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasolofo Razanamparany V, Menard D, Auregan G, Gicquel B, Chanteau S. Extrapulmonary and pulmonary tuberculosis in Antananarivo (Madagascar): high clustering rate in female patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:3964–3969. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.3964-3969.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsang CA, Langer AJ, Navin TR, Armstrong LR. Tuberculosis among foreign-born persons diagnosed /=10 years after arrival in the United States, 2010-2015. Am. J. Transplant. 2017;17:1414–1417. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chavez-Galan L, et al. Transmembrane tumor necrosis factor controls myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity via TNF receptor 2 and protects from excessive inflammation during BCG-induced pleurisy. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:999. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, et al. Identification of risk factors for extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:199–205. doi: 10.1086/380644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajagopalan S. Tuberculosis in older adults. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2016;32:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/features/dstuberculosis.

- 29.United States Renal Data System. USRDS 2017 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States (National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD). https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_01.aspx.

- 30.Al-Efraij K, et al. Risk of active tuberculosis in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2015;19:1493–1499. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin JN, et al. Risk factors for extra-pulmonary tuberculosis compared to pulmonary tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2009;13:620–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato S, et al. Aspects of immune dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;3:1526–1533. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00950208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mysore KR, et al. Longitudinal assessment of T cell inhibitory receptors in liver transplant recipients and their association with posttransplant infections. Am. J. Transplant. 2017;18:351–363. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liyanage T, et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385:1975–1982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewinsohn DM, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017;64:111–115. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris MI, et al. Diagnosis and management of tuberculosis in transplant donors: a donor-derived infections consensus conference report. Am. J. Transplant. 2012;12:2288–2300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO. Guidelines on the Management of Latent Tuberculosis Infection (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2015). [PubMed]

- 38.Volkmann T, Moonan PK, Miramontes R, Oeltmann JE. Tuberculosis and excess alcohol use in the United States, 1997-2012. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2015;19:111–119. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Happel KI, Nelson S. Alcohol, immunosuppression, and the lung. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2005;2:428–432. doi: 10.1513/pats.200507-065JS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odone A, et al. The impact of antiretroviral therapy on mortality in HIV positive people during tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janssen S, et al. Mortality in severe human immunodeficiency virus-tuberculosis associates with innate immune activation and dysfunction of monocytes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017;65:73–82. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang SL, et al. Value of procalcitonin in differentiating pulmonary tuberculosis from other pulmonary infections: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2014;18:470–477. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim J, et al. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic and prognostic factor for tuberculosis meningitis. J. Clin. Neurol. 2016;12:332–339. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2016.12.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee WS, et al. Cutoff value of serum procalcitonin as a diagnostic biomarker of infection in end-stage renal disease patients. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2015;30:198–204. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Critchley JA, et al. Defining a research agenda to address the converging epidemics of tuberculosis and diabetes: Part 1: Epidemiology and clinical management. Chest. 2017;152:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young F, Wotton CJ, Critchley JA, Unwin NC, Goldacre MJ. Increased risk of tuberculosis disease in people with diabetes mellitus: record-linkage study in a UK population. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2012;66:519–523. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.114595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Degner NR, Wang JY, Golub JE, Karakousis PC. Metformin use reverses the increased mortality associated with diabetes mellitus during tuberculosis treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;66:198–205. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beavers, S. F., et al. Tuberculosis mortality in the United States: epidemiology and prevention opportunities. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. (2018) [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Narres M, et al. The incidence of end-stage renal disease in the diabetic (compared to the non-diabetic) population: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scott C, et al. Human tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis in the United States, 2006-2013. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:594–601. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Majoor CJ, Magis-Escurra C, van Ingen J, Boeree MJ, van Soolingen D. Epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis disease in humans, The Netherlands, 1993-2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:457–463. doi: 10.3201/eid1703.101111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hlavsa MC, et al. Human tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis in the United States, 1995-2005. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;47:168–175. doi: 10.1086/589240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]