Abstract

Objective

Retailers who primarily or exclusively sell electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) or vaping products represent a new category of tobacco retailer. We sought to identify (a) how vape shops can be identified and (b) sales and marketing practices of vape shops.

Data sources

A medical librarian iteratively developed a search strategy and in February 2017 searched 7 academic databases (ABI/INFORM Complete, ECONLit, Embase, Entrepreneurship, PsycINFO, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Scopus). We hand searched Tobacco Regulatory Science and Tobacco Prevention and Cessation.

Study selection

We used dual, independent screening. Records were eligible if published in 2010 or later, were peer-reviewed journal articles, and focused on vape shops.

Data extraction

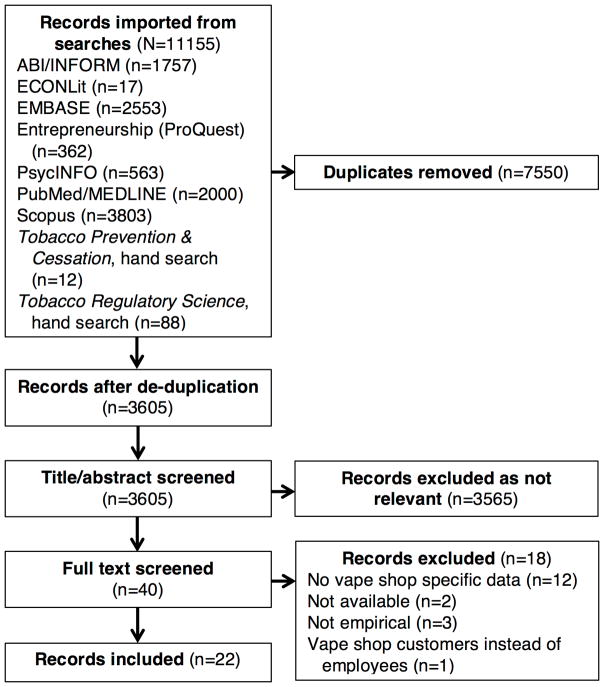

We used dual, independent data abstraction and assessed risk of bias. Of the 3,605 records identified, 22 were included.

Data synthesis

We conducted a narrative systematic review. Researchers relied heavily on Yelp to identify vape shops. Vape shop owners use innovative marketing strategies that sometimes diverge from those of traditional tobacco retailers. Vape shop staff believe strongly that their products are effective harm reduction products. Vape shops were more common in areas with more White residents.

Conclusions

Vape shops represent a new type of retailer for tobacco products. Vape shops have potential to promote e-cigarettes for smoking cessation, but also sometimes provide inaccurate information and mislabeled products. Given their spatial patterning, vape shops may perpetuate inequities in tobacco use. The growing literature on vape shops is complicated by researchers using different definitions of vape shops (e.g., exclusively selling e-cigarettes vs. also selling traditional tobacco products).

INTRODUCTION

As the tobacco epidemic has grown to include greater use of e-cigarettes and other vaping products, [1] a new type of retailer has emerged: Vape shops. These retailers focus primarily or exclusively on the sale of e-cigarettes and other vaping products (e.g., e-liquids) and differ from traditional tobacco product retailers like convenience stores or grocery stores. This recent change in the retail environment for tobacco products is important for four reasons. First, the retail environment plays an important role in normalizing tobacco use and in exposing youth to tobacco products and their advertising.[2] Second, vape shops – as specialty stores – can provide individually tailored information about e-cigarettes to consumers. Third, vape shops may utilize new forms of marketing that could promote cessation from more toxic combustible products, could draw more youth into nicotine addiction, and could promote dual use of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes.[3] Fourth, there are potential health equity issues around disproportionate marketing and presence in neighborhoods given that e-cigarettes are, at an individual level, potential harm reduction strategies for cigarette smokers.[4–6] That is, if vape shops are less accessible to low-income smokers who would benefit from quitting cigarettes, this might contribute to inequities in smoking. Alternatively, if more vape shops are located in lower-income neighborhoods, this may lead to disproportionate exposure to e-cigarettes and their marketing for lower-income youth.

Although there was a recent special issue on vape shops in Tobacco Prevention & Cessation, [7] there has not yet been an attempt to synthesize the existing knowledge on vape shops. To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review of the existing literature to answer two questions: (1) What methods are used to find, enumerate, or map vape shops? (2) What are the sales and marketing practices of vape shops?

METHODS

Search

One author (KBS) iteratively developed keywords in the domains of “e-cigarettes” and “marketing/shops” based on prior research studies, [1, 8] and combined keywords with controlled vocabulary (i.e., Medical Subject Heading [MeSH] terms) from PubMed/MEDLINE. The search strategy is available (Online Supplemental File 1). On February 27, 2017, one author (KBS) mapped and implemented the search strategy in seven databases (ABI/INFORM Complete, ECONLit, Embase, Entrepreneurship, PsycINFO, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Scopus) for peer-reviewed literature. Given that they have not been fully indexed in MEDLINE, we also hand searched all volumes and issues of Tobacco Regulatory Science and the abstracts of a special issue of Tobacco Prevention and Cessation on vape shops. We did not have any language or geographic restrictions for our search of databases. We set up article alerts to track new publications after our search; we address these findings in the discussion. We followed PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for observational studies.[9] A protocol is available (Online Supplemental File 1).

Screening

After software and manual de-duplication of records, two of three authors (JGLL, ENO, KBS) independently screened the title and abstract of each identified record for inclusion. Irrelevant records were removed from the pool and potentially relevant records were each independently reviewed in their full text form by two of three authors (JGLL, ENO, KBS). Records were eligible for inclusion if they were published during or after 2010 (as there few studies on e-cigarettes were published before that time[1] and the first newspaper article indexed by LexisNexis® about vape shops was published in October 2012[10]), were peer-reviewed journal articles, focused on vape shops and not just tobacco retailers (i.e., retailers whose primary product is e-cigarettes), and addressed one of two questions of interest: (a) What are methods used to find, enumerate, or map vape shops? (b) What are the sales and marketing practices of vape shops? We defined marketing to include Price, Promotion, Product, and Placement.[11] Covidence cloud-based software (covidence.org) was used to manage the coding process.

Abstraction

Eligible articles were independently read by two authors (JGLL, ENO) who recorded the studies’ research questions, vape shop definitions, sampling unit, sampling frame, sampling strategy, mode of data collection, analysis strategy, findings, funding source, as well as seven Risk of Bias (RoB) measures into separate data abstraction tables. As no existing RoB tool fit our needs, we developed seven RoB measures focused on the internal and external validity of each article including use of multiple geographic areas, use of random or census sampling, sample size (i.e. having over 100 vape shops included in the study), having an unrestricted sample (e.g., the sample was not limited to vape shops with prior youth sales violations), analysis appropriate to the research question, not having industry funding, and not having conflicts of interest. The two authors met to identify disagreements in the data abstraction process. A third author (KMR) resolved points of disagreement, and then the two data abstraction tables were merged into one evidence table.

Analysis

We conducted a narrative review of the identified literature as study heterogeneity in research question, design, outcomes, and reporting precluded quantitative meta-analysis. We created an evidence table following the three aims. First, we report methodological considerations. Second, we report marketing strategies. Third, we report attitudes and beliefs of owners or staff. We report marketing results by the 4 P’s (product, price, promotion, and placement).[11] Product included e-liquids, generation of e-cigarette product (i.e., first generation “cig-a-like” products that are low-cost, disposable, and ubiquitous; second generation products that often include re-fillable tanks and rechargeable batteries; and, third generation products that are highly customizable[5]). Price included discounts, buy-one-get-one sales, etc. Promotion included signage, marketing philosophy, strategies, and gifts with purchase. Placement included self-service displays and marketing materials in child’s height or line of vision. We separately report results relating to retailer density and proximity.

RESULTS

The search identified 3,605 unique records. Following the screening process, 3,565 records were deemed irrelevant to the research questions and excluded. The remaining 40 records were reviewed in their full text form. This resulted in 22 eligible records included in this systematic review. This process is shown in Figure 1. An evidence table is available in Online Supplemental File 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram, February 27, 2017

The first identified record was published in 2014.[12] Tobacco Prevention & Cessation and Tobacco Control had the largest number of records with 5 and 3, respectively. One paper was published with Canadian data, [13] one with South Korean data, [14] and the remaining 20 were from the U.S. Our risk of bias index ranged from 0 to 3 (M=1.64, SD=0.90) out of a possible seven, which indicated the most risk.

How are researchers defining vape shops?

Our inclusion criteria required that the record report data about vape shops. We thus excluded studies of e-cigarettes sold in convenience stores, [15] for example. Nonetheless, there was important variability in how researchers defined vape shops. These largely fell into two groups: (1) studies that defined vape shops as selling e-cigarettes and not selling combustible tobacco products[16–22] and (2) studies that defined vape shops as primarily selling e-cigarettes.[12–14, 23–34] As many authors were not clear about the definition used, we coded those not reporting explicitly excluding vape shops carrying combustible tobacco products into the second category. One study stratified results by type of retailer: Kong and colleagues found important differences in the marketing used by type of vape retailer by separately analyzing (a) vape shop/vape kiosk and (b) vape shops that double as smoke shops or head shops.[31]

How are researchers identifying vape shops?

The most common source for identifying vape shops is Yelp, [12, 13, 16, 19–24, 28, 30–33] which was used by 14 of the 22 records. Google was used by 8 records, [16, 21, 23, 25–27, 31, 34] Google Maps by 5, [13, 21, 30, 33, 34] Yellowpages.com by 5, [16, 24, 28, 30, 33] one used licensing lists, [30] and one used ground truthing (i.e., physically traveling a pre-defined area and canvassing streets to identify vape shop locations).[33] Ten records included other sources of information: vaporsearchusa.com, [25–27, 31, 33] Vapeabout.com, [21, 33] local health department reports, [17, 18] e-cigarette-store-reviews.com, [33] Facebook, [21] guidetovaping.com, [28] ReferenceUSA, [33] snowball sampling, [31] thevapormap.com, [31] vapestores.com, [33] Whitepages.com, [24] and an undefined convenience sample.[14]

The heavy reliance on Yelp likely stems from Sussman’s early work using Yelp as a primary source of data[12] and work by Kim et al. to validate online searches.[30] Given the existing studies, it appears that Yelp is likely one of the best single sources for identifying vape shops in the U.S.[30, 33] Yet, Yelp is imperfect; when used alone it missed almost 20% of vape shops in one small study in North Carolina.[33] That same study found the sensitivity of four vaping web sites (vapeabout.com, vaporsearchusa.com, vapestores.com, and e-cigarette-store-reviews.com) to be poor (i.e., <56). Both Kim et al. and Lee et al. found substantial numbers of false positives using Yellowpages.com.[30, 33] Based on the records identified in this review, we suggest using Yelp in combination with another online source, such as Google Maps, at least for studies in the U.S.[30, 33]

What do we know about marketing practices of vape shops and their locations?

Promotion was most commonly discussed in the records identified (n=14), [12, 13, 19, 20, 22–27, 29, 31, 32, 34] followed by product (n=6), [13, 14, 18–20, 31] price (n=2), [19, 31] and place (n=2).[20, 31] Three records looked at the density and proximity of vape shops.[16, 21, 28]

Promotion

Vape shop promotions show some differences from traditional tobacco retailer promotions, including some promotional activities that are prohibited for other regulated tobacco products.[11] One article went into detail about the differences in product promotion.[25] Cheney et al. found a clear difference: traditional tobacco product retailers rely on marketing and merchandising materials (e.g., signage, display racks, price promotions) that are created and printed by multinational tobacco companies with billions of dollars in marketing and promotion expenditures each year.[35] However, vape shops often develop their own local strategies to market their products themselves. Because of this, resources like Yelp are very important for vape shop retailers. Positive customer reviews could attract business in circumstances where marketing budgets are weak compared to tobacco industry spending for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco.[25] Further, due to the unique positioning of vape shop retailers at the point of sale, they are often in a position to provide information to customers.[25, 29] This information, a form of promotion, does not necessarily match the current evidence base of e-cigarettes as shown in this literature.[19, 25] Vape shop staff were frequently characterized as former smokers who often were current e-cigarettes users, and staff shared their personal experiences using the products to transition away from cigarettes.[23, 29, 31, 34]

Product

Product availability in this context includes discussion of e-liquids[19, 20] (including handling practices in vape shops, [20, 31] packaging/labeling, [14, 18, 31] and nicotine content/concentration levels[13, 14, 18–20]), as well as the tobacco and e-cigarette products available in vape shops.[31] Product availability mirrors increasing preference away from first-generation devices in vape shops and toward second- and third-generation devices that offer the opportunity to refill e-liquids and modify the devices.[19, 31] While records were limited in their geographic reach, they identified substantial problems with labeled nicotine concentration being inaccurate, [14, 18] lack of childproofing, [18] and customer mixing of e-liquids.[20] For example, in a study of 70 e-liquids purchased in North Dakota, 51% had 10% more or less nicotine than the label indicated.[18] The Canadian study found non-compliance with limits on e-cigarettes products.[13]

Price

Two articles discussed price. In San Francisco, when buying more than one liquid, devices and/or e-liquids were often discounted (96% and 87% of vape shops, respectively).[19] E-liquids, not the devices themselves, were the primary source of revenue and profit for these businesses.[19] In New Hampshire, over 70% of stores had price promotions on their products, which was more common in vape shops than stores selling both vape and combustible products.[31] Cross-product promotions (promoting an e-cigarette and combustible products) were rare.[31]

Placement

Two articles discussed findings regarding placement of vape products, namely self-service displays.[20, 31] Studies in Los Angeles and New Hampshire noted rates of e-liquid self-service at 83% and 16.4% respectively, illustrating a large discrepancy between vape shops.[31] At the time of the literature search, vape product placement was not yet regulated by the FDA.

Density and Proximity

We identified three records about density or proximity.[16, 21, 28] These records found that vape shops are more likely to be concentrated near college and university campuses[28] and are patterned in opposite ways of conventional tobacco retailers (i.e., they are more likely to be present in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of White residents) in New Jersey.[21] Similar to conventional tobacco retailers, there are substantial numbers of primary and secondary schools that have a vape shop present nearby (but that the presence of a vape shop was not associated with use of e-cigarettes among youth at the school).[16]

Staff and Owner Attitudes and Beliefs

Seven articles discuss perspectives from store owners/staff members or owners of vape shops.[19, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 34] Interviews with vape shop owners, as illustrated by this literature, show a positive view of e-cigarettes, reflected from the interviewee’s own experience and often conveyed to the customer.[19, 23, 27, 29, 34] Vape shop staff want to help smokers quit combustible cigarettes but showed little interest in addressing nicotine addiction.[22, 27, 29, 34] As salespeople of a fairly new product, the owners/staff members have the unique positioning to share their knowledge to an interested consumer. Their knowledge, however, is primarily limited to what the staff has read on the internet, as opposed to science-based evidence.[27, 34] For instance, in one record, an important source of information reported was YouTube videos from the vaping industry.[27] Finally, vape shop staff reported mixed feelings about FDA regulation: They appreciated limits that reduced unscrupulous competitors and safety concerns but worried about FDA regulations limiting innovation and being co-opted by the tobacco industry.[26]

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

Vape shops differ from tobacco retailers as they are often individually owned, receive no or few resources from the major tobacco companies, and sell a relatively new product that is only recently subject to regulations. There are, however, some similarities of marketing practices between traditional tobacco product retailers and vape shops. These included use of price promotions and loyalty programs. Although vape shop staff and owners frequently report caring deeply about helping people quit smoking cigarettes, they placed little emphasis on reducing addiction to nicotine. Information provided on products, which can often be customized or mixed on premises, may be misleading. The identified research, which is limited and may be subject to change as more studies emerge, suggests vape shops are disproportionately concentrated in areas with more White residents and in higher income areas. In as much as vape shops are purveyors of a potential harm-reduction product for individual smokers, this disparity, if confirmed in future studies, represents a potential health equity issue. Alternatively, vape shops do market a product that, when containing nicotine, is both addictive and detrimental to health. Greater presence of vape shops in one area versus another may come with consequences. These could include increased youth initiation and increased dual use of vaping products with conventional cigarettes.

Study Findings in Context

Defining and Finding Vape Shops

Yelp, used in combination with other data sources such as licensing lists or Google Maps, is recommended for identifying vape shops in the U.S. When vape shops were defined in the literature, they were classified in two groups: retailers who sell e-cigarettes without selling any traditional, combustible tobacco products and those retailers who primarily sell e-cigarettes but may still sell some combustible tobacco products. From the existing literature, we believe it is clear that future studies should be inclusive of multiple types of e-cigarette retailers but should stratify results by type of e-cigarette retailer. We return to this point below in reference to studies of tobacco retailer density.

Marketing

Like other tobacco retailers, vape shops use the 4 P’s of marketing to drive sales. While tobacco promotions are common at tobacco retailers (e.g., an average tobacco retailer has 29.5 marketing materials), [36] vape shops often rely on word of mouth referrals, discounts, and customer service approaches to driving sales. This is likely due to the focus on second- and third-generation e-cigarettes products and the limited sale of increasingly tobacco-industry owned cig-a-like products (or first generation) products. The different combinations of marketing strategies should be monitored as the tobacco industry acquires and markets newer e-cigarette products.[37] One study from Los Angeles, California, published after the date of our search found differences in marketing practices by the predominant ethnicity of the neighborhood. This 2014 study of 77 vape shops found more self-service samples in predominantly Korean and non-Hispanic White neighborhoods than in African-American or Hispanic neighborhoods.[38]

Regarding the location of vape shops, the included records suggested (1) substantial presence of vape shops near primary/secondary schools;[16] (2) clustering near colleges and universities;[28] and, (3) in a study from New Jersey, that vape shops do not follow the general patterning of tobacco retailers (i.e., with more retailers in neighborhoods with higher proportions of African-American residents).[21] This last finding is consistent with the sale of e-cigarettes at traditional tobacco retailers.[15] It conflicts with a national study published after our search showing vape shop density is similar to tobacco retailer density (i.e., correlated with proportion African-American residents);[39] however, this is may be the result of inclusion of tobacco retailers that sell e-cigarettes products.[40]

As noted by Giovenco in a research letter published after our search, different definitions of vape shops can lead to quite different results in density/proximity studies.[40] Inclusion of vape shops that also sell conventional tobacco products may explain differences regarding neighborhood correlates of vape shop presence or density. It is clear that both the definition of vape shops and the construction of vape shop density datasets require attention as the field moves forward. We suggest the use of clear definitions and stratification of results by definition used.

Attitudes and Beliefs

Perhaps the single biggest contrast between vape shops and traditional tobacco retailers is in the clearly articulated belief and desire to help people stop smoking conventional cigarettes. In one study published after our search, data collectors posing as customers asked questions about vaping products in 18 vape shops in Southern California and recorded marketing claims. Frequent claims included e-cigarettes’ potential as cessation devices and about health benefits of switching.[41] However, in qualitative research identified in our study, this desire to help customers stop smoking cigarettes did not extend to reductions in nicotine addiction. Given that quitting all forms of tobacco and nicotine use is desirable for population health, this is a substantial concern. It also represents an important consideration for future efforts to leverage the harm-reduction potential of vape shops.

Vape shop owners/staff were also concerned with both regulation (its limits on their business practices and co-option by the tobacco industry) and with the lack of regulation (unscrupulous competitors and poor product quality and safety).

Regulation

The included records have several important implications for regulators. First, given challenges in identifying vape shops, vape shops should be considered for inclusion in tobacco retailer licensing programs. Such licensing programs should be able to identify retailers that sell only vaping products (i.e., do not sell combustible or smokeless tobacco). New York City for instance, licenses retailers that sell e-cigarettes separately from stores that sell other tobacco products. One could estimate the number of shops selling on vaping products by comparing the lists. Second, given problematic accuracy of labeling and self-service of e-liquids, regulators should consider additional requirements, enforcement, and inspection protocols in these areas. Third, youth access inspection programs for vape shops may need to be different than those of traditional tobacco retailers. In one study published after our search, rates of sales to youth of e-cigarettes and cigarettes were similar; however, vape shops were not specifically examined.[42] Further research on sales to youth is likely needed. Fourth, as the evidence of benefits versus risks to population health from the presence of vape shops becomes clearer, policies regarding retailer proximity and density should either seek to promote the equitable presence of vape shops or limit their presence in vulnerable areas.

Limitations

This systematic review is limited by the recent emergence of literature on vape shops. Thus, data in some areas are still thin. We did not search the gray literature, and this review, like all reviews, is subject to publication bias. Nonetheless, our search was developed by a professional medical librarian, we implemented the search in multiple academic databases, we used rigorous dual coding for inclusion and abstraction, and we assessed risk of bias in the included studies. The literature is still young and does not reflect the increasing ownership of vaping manufacturers by the tobacco industry. As industry ownership increases, some home-grown marketing efforts may be replaced by the sophisticated calibration of the tobacco industry and product innovations may take different directions.[37] Vape shop practices and regulations are in flux and may continue to evolve. Additionally, many of the papers covered limited geography, predominantly U.S.-based (e.g., a single region in California, North Carolina, or Oklahoma), and almost a quarter of all the included studies (23%) came from the same research group using data on vape shops in Los Angeles, California.[12, 20, 22, 23, 32] These studies may not generalize to other locations both in and outside of the U.S.

Conclusion

The emergence of vape shops represents an interesting challenge for policymakers seeking to promote harm reduction among smokers while also seeking to limit the dissemination of inaccurate information, inaccurately labeled products, and marketing that could lure youth or sustain harmful addiction through dual use. Vape shops also challenge researchers to critically assess what constitutes a vape shop and how to accurately identify vape shops with sensitivity and specificity. Continued surveillance of vape shop marketing practices is warranted as are efforts to assess the equity effects of vape shop marketing, density, and proximity.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

E-cigarettes are an emerging product with potential for individual harm reduction but also with risks to population health. Vape shops are a new form of retailer selling addictive products.

The evidence about the sales and marketing practices of vape shops, as well as methodological concerns about their identification, has not been synthesized.

This study identifies best practices in vape shop identification, marketing strategies used by vape shops, and considers potential equity concerns given where vape shops are located.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the U.S. National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01CA154281. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. An earlier version of this manuscript was presented at the 2017 National Conference on Tobacco or Health in Austin, Texas. Kurtis G. Kozel kindly provided his editing skills to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

K. M. Ribisl serves as an expert consultant in litigation against cigarette manufacturers. J. G. L. Lee and K. M. Ribisl have a royalty interest in store mapping and audit systems owned by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, but these systems were not used in this study.

References

- 1.Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions and beliefs: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2014;23(5):375–384. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Wang Y, et al. Association of retail tobacco marketing with adolescent smoking. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2081–2083. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu SH, Zhuang YL, Wong S, et al. E-cigarette use and associated changes in population smoking cessation: evidence from US current population surveys. Bmj. 2017;358:j3262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatnagar A, Whitsel LP, Ribisl KM, et al. Electronic cigarettes: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(16):1418–1436. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, et al. E-cigarettes: An evidence update. London, UK: Public Health England; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sussman S, Barker DC. Vape shops: The e-cigarette marketplace. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. 2017;2(Supplement):11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):Cd010216. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bro D. Switch to e-cigs inspires local entrepreneurs. Orange County Register (California) 2012:B. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):147–153. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sussman S, Garcia R, Cruz TB, et al. Consumers’ perceptions of vape shops in Southern California: an analysis of online Yelp reviews. Tobacco induced diseases. 2014;12(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12971-014-0022-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond D, White CM, Czoli CD, et al. Retail availability and marketing of electronic cigarettes in Canada. Canadian journal of public health = Revue canadienne de santé publique. 2015;106(6):e408–e412. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.106.5105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Goniewicz ML, Yu S, et al. Variations in label information and nicotine levels in electronic cigarette refill liquids in South Korea: Regulation challenges. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12(5):4859–4868. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120504859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose SW, Barker DC, D’Angelo H, et al. The availability of electronic cigarettes in US retail outlets, 2012: results of two national studies. Tob Control. 2014;23(Suppl 3):iii10–16. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bostean G, Crespi CM, Vorapharuek P, et al. E-cigarette use among students and e-cigarette specialty retailer presence near schools. Health and Place. 2016;42:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buettner-Schmidt K, Miller DR. An observational study of compliance with North Dakota’s smoke-free law among retail stores that sell electronic smoking devices. Tobacco control. 2017;26(4):452–454. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buettner-Schmidt K, Miller DR, Balasubramanian N. Electronic Cigarette Refill Liquids: Child-Resistant Packaging, Nicotine Content, and Sales to Minors. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2016;31(4):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burbank A, Thrul J, Ling P. Characterizing Retail ‘Vape Shops’: A Pilot Study of Retail ‘Vape Shops’ in the San Francisco Bay Area. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. 2016;2(September) doi: 10.18332/tpc/65229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia R, Allem J, Baezconde-Garbanati L, et al. Employee and customer handling of nicotine-containing e-liquids in vape shops. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. 2016;2(Supplement) doi: 10.18332/tpc/67295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovenco DP, Duncan DT, Coups EJ, et al. Census tract correlates of vape shop locations in New Jersey. Health and Place. 2016;40:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai J, Bluthenthal R, Allem J-P, et al. Vape Shop Retailers’ Perceptions of Their Products, Customers, and Services: A Qualitative Study. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. 2016;2(Supplement) doi: 10.18332/tpc/70345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allem J-P, Unger JB, Garcia R, et al. Tobacco attitudes and behaviors of vape shop retailers in Los Angeles. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2015;39(6):794–798. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.6.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basch CH, Kecojevic A, Menafro A. Provision of information regarding electronic cigarettes from shop employees in New York City. Public Health. 2016;136:175–177. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheney M, Gowin M, Wann TF. Marketing Practices of Vapor Store Owners. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(6):E16–E21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheney MK, Gowin M, Wann TF. Vapor Store Owner Beliefs about Electronic Cigarette Regulation. Tobacco Regulatory Science. 2015;1(3):227–235. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheney MK, Gowin M, Wann TF. Vapor Store Owner Beliefs and Messages to Customers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2016;18(5):694–699. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai H, Hao J. Geographic density and proximity of vape shops to colleges in the USA. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):379–385. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart J, Walker K, Sears C, et al. Vape Shop Employees: Public Health Advocates? Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. 2016;2(Supplement) doi: 10.18332/tpc/67800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim AE, Loomis B, Rhodes B, et al. Identifying e-cigarette vape stores: description of an online search methodology. Tobacco Control. 2016;25(e1) doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong AY, Eaddy JL, Morrison SL, et al. Using the Vape Shop Standardized Tobacco Assessment for Retail Settings (V-STARS) to Assess Product Availability, Price Promotions, and Messaging in New Hampshire Vape Shop Retailers. Tobacco Regulatory Science. 2017;3(2):174–182. doi: 10.18001/TRS.3.2.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong G, Unger J, Baezconde-Garbanati L, et al. The Associations between Yelp Online Reviews and Vape Shops Closing or Remaining Open One Year Later. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. 2016;2(Supplement) doi: 10.18332/tpc/67967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JG, D’Angelo H, Kuteh JD, et al. Identification of Vape Shops in Two North Carolina Counties: An Approach for States without Retailer Licensing. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2016;13(11) doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nayak P, Kemp CB, Redmon P. A Qualitative Study of Vape Shop Operators’ Perceptions of Risks and Benefits of E-Cigarette Use and Attitude Toward Their Potential Regulation by the US Food and Drug Administration, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, or North Carolina, 2015. Preventing chronic disease. 2016;13:E68. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2013. Washington, DC: Author; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ribisl KM, D’Angelo H, Feld AL, et al. Disparities in tobacco marketing and product availability at the point of sale: Results of a national study. Prev Med. 2017;105:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seidenberg AB, Jo CL, Ribisl KM. Differences in the design and sale of e-cigarettes by cigarette manufacturers and non-cigarette manufacturers in the USA. Tob Control. 2016;25(e1):e3–5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia R, Sidhu A, Allem J, et al. Marketing activities of vape shops across racial/ethnic communities. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. 2017;2(Supplement):12. doi: 10.18332/tpc/76398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dai H, Hao J, Catley D. Vape Shop Density and Socio-Demographic Disparities: A US Census Tract Analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(11):1338–1344. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giovenco DP. Smoke shop misclassification may cloud studies on vape shop density. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang JS, Wood MM, Peirce K. In-person retail marketing claims in tobacco and E-cigarette shops in Southern California. Tobacco induced diseases. 2017;15:28. doi: 10.1186/s12971-017-0134-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levinson AH. Nicotine sales to minors: Store-level comparison of e-cigarette vs. cigarette violation rates. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.