Abstract

Prior studies demonstrate that most living kidney donors (LKDs) report no adverse psychosocial outcomes; however, changes in psychosocial functioning at the individual donor level have not been routinely captured. We studied psychosocial outcomes pre-donation and at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months post-donation in 193 LKDs and 20 healthy controls (HCs). There was minimal to no mood disturbance, body image concerns, fear of kidney failure, or life dissatisfaction, indicating no incremental changes in these outcomes over time and no significant differences between LKDs and HCs. The incidence of any new-onset adverse outcomes post-donation was as follows: mood disturbance (16%), fear of kidney failure (21%), body image concerns (13%), and life dissatisfaction (10%). Multivariable analyses demonstrated LKDs with more mood disturbance symptoms, higher anxiety about future kidney health, low body image, and low life satisfaction prior to surgery were at highest risk of these same outcomes post-donation. Importantly, some LKDs showed improvement in psychosocial functioning from pre- to post-donation. Findings support the balanced presentation of psychosocial risks to potential donors as well as the development of a donor registry to capture psychosocial outcomes beyond the mandatory two-year follow-up period in the USA.

INTRODUCTION

Living kidney donors (LKDs) account for one-third of kidney transplants annually in the United States.1 LKDs are not only a critical source of transplantable organs, but they provide kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) with the most optimal short- and long-term outcome and help reduce healthcare costs associated with renal failure. LKDs themselves do not derive any medical benefit from donation, although they may benefit psychologically from helping another.2,3 Consequently, the transplant community is committed to ensuring the safety of donor nephrectomy and minimizing donation risks. Surgical and medical outcomes following living donation, for instance, have been characterized and continue to be targets of ongoing investigation.4–9

Psychosocial outcomes are described in multiple studies, which generally report that most LKDs experience no serious deleterious psychosocial consequences from donation.10–13 Many studies, however, have been cross-sectional and limited to a single center. More recent prospective studies found that some LKDs experience considerable financial loss and health insurance problems14–17, although the full range of psychosocial outcomes has not been explored in large, multi-center prospective studies.18 Additionally, while average or mean scores on psychosocial outcomes suggest favorable outcomes overall, changes in psychosocial functioning at the individual donor level are not routinely captured.14 This requires examining each outcome for each individual LKD to assess whether any meaningful change has occurred over time. More refined examination of these outcomes is necessary to better inform potential LKDs about the short- and long-term effects of donation along dimensions that may be important to them and how these outcomes may change over time.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Kidney Donor Outcomes Cohort (KDOC) study is a multi-center, prospective study of LKD outcomes. We previously reported on the financial impact of living donation.16,18 Now, we report on five other psychosocial outcomes – mood, fear of kidney failure, body image, life satisfaction, and decisional stability. These particular outcomes were selected for study because regulations have required programs to inform potential LKDs about their possible occurrence after donation (e.g., depression, body image concerns), former LKDs identified them to our study group as being of high interest to potential donors, and prior literature as well as clinical experiences of the study team suggested they were of high clinical relevance and necessitated further study. The aims of the current analysis were twofold: (1) to characterize the incidence of adverse psychosocial outcomes post-donation, and (2) to identify pre-donation characteristics or variables associated with higher risk of adverse psychosocial outcomes. Identifying pre-donation characteristics associated with poor psychosocial outcomes following donation may help to improve the evaluation and informed consent process for future potential LKDs. On the basis of prior research findings10, we hypothesized that a history of depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder or substance use disorder may be associated with worse post-donation psychosocial functioning. Additionally, we hypothesized that higher BMI may be associated with lower post-donation body image.

METHODS

Kidney Donor Outcomes Cohort (KDOC)

The KDOC study (www.kdocstudy.com) examined surgical, medical, psychosocial, functional, and cost outcomes collected prospectively from LKDs, along with outcome data for their intended KTRs, at six transplant programs in the United States (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA; Maine Medical Center, Portland, ME; Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY; Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI; University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ; and University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). These programs performed between 20 and 36 live donor kidney transplants (LDKTs) annually during the study period, representing 37% of total kidney transplants (living and deceased) across participating programs.

We also recruited healthy controls (HCs) into the study if they underwent evaluation but did not donate because imaging showed an anatomical issue that would not be expected to affect medical outcomes, the recipient received a deceased donor transplant or a LDKT using a different donor, or the recipient was no longer eligible for transplantation.

Because this was an observational cohort study, participating programs used their existing policies and practices to conduct medical, surgical, and psychosocial evaluation for donor candidates. Only LKDs who were approved for donation using local criteria and who met study inclusion criteria (≥18 years, English or Spanish language) were recruited for study participation from September 2011 to November 2013. Following written informed consent, the pre-donation assessment was completed and we then attempted to recruit the LKD’s intended recipient into the study. The assessment protocol, which included several questionnaires, was re-administered at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months post-donation and completed electronically or by mail. KTRs and HCs completed a shorter assessment at these same time points. Follow-up telephone calls and/or emails were made by research staff to maximize data completeness. Participants were paid $20 for completing each psychosocial assessment. Medical record data were gathered and submitted via the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system (www.project-redcap.org), a secure online research portal, by study coordinators at all sites. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all data collection sites.

Psychosocial Outcomes

Mood

Ten adjectives from the Profile of Mood States (POMS; Cronbach’s α = 0.83)20 were used to assess three constructs – anxiety (tense, anxious, nervous), depression (helpless, unhappy, hopeless, worthless), and anger (angry, grouchy, resentful) – and total mood disturbance. For each adjective, LKDs and HCs indicated how they felt in the past week (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely), with higher scores indicating more mood disturbance. A total score >10 indicates the presence of possible mood disturbance.20

Fear of kidney failure

The 5-item Fear of Kidney Failure (FKF; α = 0.91)21 questionnaire (1 = not at all fearful to 4 = very fearful) was used to measure anxiety about possible kidney injury or failure. A score >10 suggests moderate to high fear or anxiety about future kidney-related health.21

Body image

The 10-item Body Image Scale (BIS; α = 0.92)22 was used to measure concerns about general body image issues (e.g., feeling self-conscious, dissatisfied with body) and body image in relation to donor surgery (e.g., less physically attractive, body less whole). Participants indicated how they felt in the past week (0 = not at all to 3 = very much), with higher scores representing poorer body image. A total score ≥10 indicates heightened body image concerns.23 Additionally, LKDs were asked to rate their overall satisfaction (1 = not at all satisfied, 5 = extremely satisfied) with surgical scarring at the 6 month assessment.

Life satisfaction

The 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; α = 0.88)24 measures global satisfaction with one’s life. Individual items (1 = strong disagree to 7 = strongly agree) are summed to yield a total score ranging from 5 to 35, with higher scores indicating more life satisfaction. It has been used in a variety of samples, including transplant candidates and LKDs. A total score <20 is indicative of low life satisfaction.25

Decisional stability

To assess decision stability over time, we asked LKDs the following question: “In thinking about your whole donation experience so far, from the time you first thought about it to now, would you make the same decision to be a living donor if you had to do it all over again?” (Yes, No, or Not Sure). Also, we asked LKDs to rate their overall satisfaction with the donation experience (1 = not at all satisfied, 5 = extremely satisfied).

Possible Pre-donation Predictors of Psychosocial Outcomes

LKD sociodemographic characteristics

We examined age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, health insurance, life insurance, organ donation registration status, and annual household income.

LKD clinical characteristics

We examined several clinical variables at baseline, including mood disorder and substance abuse history, body mass index (BMI), physical and mental quality of life, and dispositional optimism. Mood disorder and substance abuse history as well as BMI were obtained from medical record review. Perceived quality of life at baseline was examined using the SF-36 Health Survey26, which yields composite scores for physical and mental health and has been used extensively with LKDs and KTRs. Finally, LKDs completed the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R)27 at baseline to measure dispositional optimism, a construct found to be associated with more favorable psychosocial functioning. The LOT-R yields a total score ranging from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more optimism.

Donation-related variables

Donor-recipient relationship type (biological, spouse, unrelated) and perceived emotional closeness (1=not at all close to 7=extremely close) were examined. Also, we assessed LKDs’ knowledge about living donation (20 true-false items, scores range from 0 to 20, higher scores = more knowledge) and concerns about living donation (20 items, 5-point Likert scale, scores range from 20 to 100, higher scores = more concerns).28 Finally, we assessed whether LKDs felt any pressure from others to go through with donation and the perceived convenience of donation (1=not at all convenient, 5=extremely convenient).

KTR clinical characteristics

We examined the KTR’s pre-donation dialysis status and physical and mental quality of life (SF-36 Health Survey)26.

Statistical Analysis

Data collection, entry, and validation were facilitated via REDCap and statistical analyses conducted using R 3.4.0 (R Development Core Team, 2017) and SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all psychosocial outcomes and pre-donation predictor variables. We calculated t tests to examine for differences between LKDs and HCs on pre-donation sociodemographics and on dependent measures at all time points. We performed a series of repeated measure generalized estimating equations to assess whether LKDs and HCs differed in their trajectories over time for three psychosocial outcomes: mood, body image and satisfaction with life (HCs did not complete the FKF questionnaire over time). For each of the models, we adjusted for the baseline variable of interest and examined the interaction between group (donor vs. control) and time. LKDs who dropped out or who missed assessment time points were included in the analysis since modeling accounts for participants with varying degrees of follow-up. Next, using the clinical cut-off scores identified previously, for each LKD and HC we determined whether their score on each psychosocial outcome measure was in the clinical range and whether this remained in the clinical range at any post-donation time point or not. Those LKDs and HCs who completed the pre-donation assessment and ≥1 post-donation psychosocial assessment were included in this analysis. The percentage of LKDs and HCs with clinical and non-clinical scores on each psychosocial outcome measure, from pre- to post-donation, was then calculated. Next, we used unadjusted logistic regression models to examine the relationship between LKD sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, donation-related variables, and KTR clinical characteristics and LKD post-donation psychosocial outcomes. For each psychosocial outcome (mood, fear of kidney failure, body image, life satisfaction), LKDs were classified as having a score in the non-clinical versus clinical range at any time point following donation. Again, only LKDs who completed the pre-donation assessment and at least one post-donation psychosocial assessment were included in the models. For each model, to assess for multicollinearity we examined the variance inflation factor (>5 indicating multicollinearity) and the correlation coefficients among the predictor variables (r > -.80 indicating multicollinearity). Pre-donation variables with an unadjusted odds ratio p < 0.01 in the univariate screen were included in the multivariable regression model examining pre-donation predictors of post-donation outcomes (clinical vs. non-clinical score).

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

Characteristics of LKDs (n=193), KTRs (n=152), and HCs (n=20) are reported in Table 1. One-hundred ninety-four LKDs (84% of eligible donors during enrollment period) were enrolled into the KDOC study. However, one enrolled LKD died during surgery and the kidney was not transplanted, thus the participant was removed from the current analysis. As previously reported16, the LKD sample characteristics are similar to adults who donated a kidney in the United States during the KDOC enrollment period, with the exception of more college educated donors in the KDOC sample (P=0.01). Participation rates for KTRs and HCs were 66% and 83%, respectively.

Table 1.

Pre-donation characteristics of the KDOC living kidney donors (LKDs), transplant recipients (KTRs), and healthy controls (HCs)

| Variable | LKDs (n=193) |

KTRs (n=152) |

HCs (n=20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age, yrs, mean (SD) | 42.6 (11.8) | 51.1 (14.1) | 41.1 (15.0) |

| Sex, female | 122 (63%) | 61 (40%) | 12 (60%) |

| Race, White, non-Hispanic | 147 (76%) | 116 (76%) | 14 (70%) |

| Education, college or professional degree | 98 (51%) | 69 (45%) | 10 (50%) |

| Marital status, married/partnered | 99 (51%) | 99 (65%) | 11 (55%) |

| Work status, employed | 152 (79%) | 71 (47%) | 15 (75%) |

| Health insurance, yes | 172 (89%) | – | 18 (90%) |

| Life insurance, yes | 122 (63%) | – | 8 (40%) |

| Household income, ≥ $50,000 | 123 (64%) | 85 (56%) | 10 (50%) |

| Register organ and tissue donor, yes | 127 (66%) | – | 13 (65%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| History of mood disorder, yes | 46 (24%) | – | 1 (5%) |

| History of substance abuse (remission), yes | 11 (6%) | – | 3 (15%) |

| Prescribed psychiatric medication, yes | 33 (17%) | – | 0 (%) |

| Body mass index, mean (sd) | 27.1 (3.8) | – | 27.1 (3.2) |

| SF-36 physical health component, mean (SD) | 57.2 (4.9) | 41.0 (9.8) | 56.2 (4.6) |

| SF-36 mental health component, mean (SD) | 54.3 (6.5) | 47.7 (10.4) | 53.2 (10.7) |

| LOT-R optimism, mean (SD) | 17.5 (3.7) | – | 18.3 (3.9) |

| Dialysis, yes | – | 87 (57%) | – |

| Donation-related variables | |||

| Relationship to recipient/donor | |||

| Biological | 111 (58%) | 83 (55%) | 7 (35%) |

| Spouse | 32 (17%) | 31 (20%) | 3 (15%) |

| Unrelated | 50 (26%) | 38 (25%) | 10 (50%) |

| Emotional closeness with recipient, mean (SD) | 5.8 (1.7) | – | 4.0 (2.5) |

| Living donation knowledge, mean (SD) | 12.9 (1.1) | – | 12.7 (1.7) |

| Living donation concerns, mean (SD) | 29.4 (7.7) | – | 30.2 (6.5) |

| Pressure from others to donate, yes | 19 (10%) | – | 3 (15%) |

| Convenience of donation, mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.2) | – | – |

Psychosocial assessment completion rates for LKDs were as follows: 98% (n=189) at pre-donation baseline, 92% (n=177) at 1 month, 83% (n=161) at 6 months, 81% (n=156) at 12 months, and 85% (n=163) at 24 months. One-hundred eighty-two LKDs (94%) completed the pre-donation baseline assessment and ≥1 follow-up psychosocial assessment and 138 (72%) completed all follow-up psychosocial assessments. Those who did not complete a follow-up assessment were younger than those who completed ≥1 follow-up assessment (P=0.03), but did not otherwise differ based on sex, race, education, marital status, or household income.

Psychosocial Outcomes

Psychosocial outcomes for both LKDs and HCs are summarized in Table 2. On average, there was minimal to no mood disturbance, body image concerns, fear of kidney failure, and life dissatisfaction at all time points, suggesting no incremental changes in these constructs over time. Analytic models showed no significant differences between LKD and HC trajectories over time for total mood disturbance, body image, and life satisfaction scores (all P values >0.05).

Table 2.

Psychosocial outcomes at each of the assessment time points.

| Psychosocial Outcome | Pre-donation | 1 month post-donation | 6 months post-donation | 12 months post-donation | 24 months post-donation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| LKD (n=189) |

HC (n=19) |

LKD (n=177) |

HC (n=19) |

LKD (n=161) |

HC (n=18) |

LKD (n=156) |

HC (n=17) |

LKD (n=163) |

HC (n=15) |

|

| Mood | 5.04 (4.4) | 6.16 (4.9) | 3.66 (4.3) | 4.95 (5.1) | 4.69 (5.8) | 5.28 (4.3) | 4.65 (5.0) | 6.00 (4.8) | 5.07 (5.5) | 4.93 (4.5) |

| Anxiety | 3.26 (2.6) | 2.95 (2.6) | 1.69 (2.0) | 2.42 (2.4) | 2.20 (2.2) | 2.22 (2.4) | 2.06 (2.2) | 2.29 (2.5) | 2.25 (2.3) | 2.20 (2.3) |

| Depression | 0.62 (1.2) | 1.16 (2.0) | 0.92 (1.5) | 1.05 (2.1) | 1.18 (2.5) | 1.06 (1.3) | 1.13 (2.0) | 1.38 (2.1) | 1.21 (2.2) | 0.93 (1.5) |

| Anger | 1.17 (1.6) | 2.05 (1.2) | 1.05 (1.4) | 1.47 (1.3) | 1.32 (1.7) | 2.00 (1.7) | 1.47 (1.8) | 2.18 (1.5) | 1.63 (1.8) | 1.80 (1.1) |

| Fear of kidney failure | 8.21 (3.8) | 8.21 (2.9) | 7.23 (3.0) | – | 7.69 (3.6) | – | 7.79 (3.8) | – | 7.86 (3.3) | – |

| Body image | 4.37 (4.8) | 5.16 (3.2) | 4.30 (5.0) | – | 3.49 (4.2) | 4.94 (3.4) | 3.41 (4.2) | 4.24 (3.0) | 3.23 (3.7) | 4.64 (2.4) |

| Surgical scarring satisfaction | – | – | – | – | 3.72 (1.3) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Life satisfaction | 27.94 (5.5) | 29.0 (5.0) | 27.82 (5.4) | 27.63 (6.4) | 27.93 (5.7) | 28.06 (5.0) | 27.77 (6.1) | 28.47 (5.1) | 27.87 (5.9) | 28.67 (5.9) |

| Decisional stability | – | – | 6 (3%) | – | 5 (3%) | – | 2 (1%) | – | 3 (2%) | – |

| Donation satisfaction | – | – | 4.31 (0.8) | – | 4.35 (0.7) | – | 4.41 (0.8) | – | 4.49 (0.7) | – |

In the absence of mean differences between LKDs and HCs, we assessed for change from pre- to post-donation for individual LKDs and for change over time for individual HCs. Specifically, we categorized each LKD and HC as having either a “clinical” or “non-clinical” total mood disturbance, fear of kidney failure, body image concern, or life dissatisfaction score prior to donation and whether scores in these domains reached a “clinical” level at any point during the 2 year follow-up period. Only the 182 LKDs and 19 HCs who completed the pre-donation assessment and ≥1 follow-up psychosocial assessment were examined.

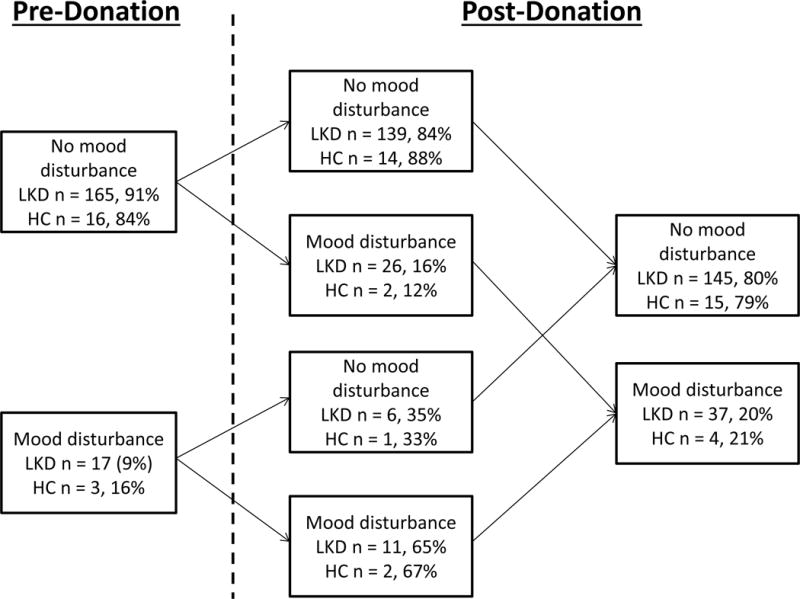

Mood

The majority of LKDs (n=165, 91%) reported no pre-donation total mood disturbance (Figure 1). Most (n=139, 84%) without pre-donation mood disturbance had no clinically significant worsening of mood following donation; however, 26 (16%) LKDs with non-clinical mood scores at pre-donation reported clinically elevated mood disturbance scores at one or more post-donation assessments. Among the 17 (9%) with pre-donation mood disturbance, 6 (35%) reported complete improvement in mood disturbance symptoms and 11 (65%) reported continued mood disturbance following donation. Overall, 37 (20%) LKDs reported moderate to severe mood disturbance at ≥1 post-donation time point. Nearly identical patterns were seen for the small HC cohort (Figure 1). In multivariable analysis of LKDs, we found that younger age and pre-donation mood disturbance were significantly associated with higher total mood disturbance post-donation (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Number and percentage of Living Kidney Donors (LKD) and Healthy Controls (HC) with clinical change in total mood disturbance over time, LKD N = 182 and HC N = 19

Table 3.

Multivariate predictors of post-donation psychosocial outcomes.

| Outcomes | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood disturbance | ||||

| Age | 0.94 (0.91,0.97) | < 0.001 | 0.95 (0.90,0.99) | 0.001 |

| Donor mental QOL | 0.88 (0.83,0.93) | < 0.001 | 0.94 (0.87,1.02) | 0.14 |

| Optimism | 0.84 (0.75,0.93) | 0.001 | 0.93 (0.82,1.05) | 0.23 |

| Pre-donation mood disturbance | 1.24 (1.13,1.37) | < 0.001 | 1.17 (1.04,1.33) | 0.01 |

| Pre-donation life satisfaction | 0.91 (0.86,0.97) | 0.004 | 1.00 (0.92,1.09) | 0.99 |

| Fear of kidney failure | ||||

| Age | 0.96 (0.93,0.99) | 0.001 | 0.99 (0.95,1.03) | 0.70 |

| Marital status (married) | 0.27 (0.14,0.53) | < 0.001 | 0.31 (0.14,0.68) | 0.004 |

| Optimism | 0.87 (0.79,0.95) | 0.002 | 0.90 (0.81,1.00) | 0.06 |

| Pre-donation fear of kidney failure | 1.34 (1.21,1.52) | < 0.001 | 1.30 (1.13,1.51) | < 0.001 |

| LDKT concerns | 1.06 (1.02,1.11) | 0.005 | 1.00 (0.94,1.06) | 0.97 |

| Body image concerns | ||||

| Donor mental QOL | 0.94 (0.89,0.98) | 0.002 | 0.96 (0.92,1.04) | 0.29 |

| Pre-donation mood disturbance | 1.15 (1.04,1.22) | 0.005 | 0.97 (0.85,1.09) | 0.69 |

| Pre-donation body image concerns | 1.22 (1.16,1.29) | < 0.001 | 1.12 (1.03,1.23) | 0.002 |

| Perceived donation pressure (yes) | 4.36 (1.97,16.11) | 0.002 | 4.01 (1.29,13.60) | 0.02 |

| Life dissatisfaction | ||||

| Race (white) | 0.32 (0.15,0.71) | 0.005 | 0.16 (0.04,0.51) | 0.003 |

| Marital status (married) | 0.31 (0.13,0.67) | 0.004 | 0.43 (0.14,1.21) | 0.13 |

| Donor mental QOL | 0.92 (0.87,0.97) | 0.001 | 0.99 (0.91,1.08) | 0.72 |

| Pre-donation mood disturbance | 1.19 (1.09.1.30) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (0.93,1.25) | 0.36 |

| Pre-donation body image concerns | 1.11 (1.03,1.20) | 0.006 | 1.06 (0.94,1.20) | 0.42 |

| Pre-donation life dissatisfaction | 0.80 (0.73,0.86) | < 0.001 | 0.82 (0.73,0.89) | < 0.001 |

| LDKT concerns | 1.09 (1.04,1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (0.97,1.10) | 0.36 |

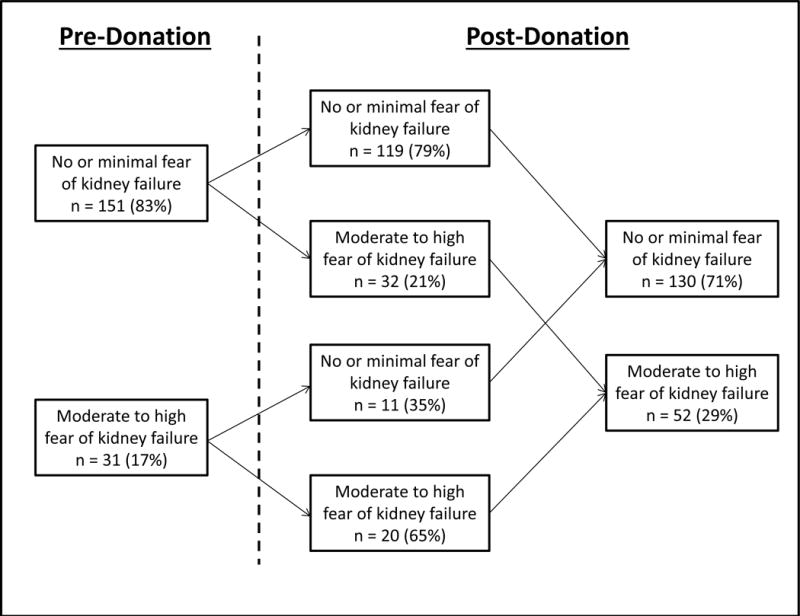

Fear of kidney failure

The majority of LKDs (n=151, 83%) reported no or minimal fear of kidney failure prior to donation (Figure 2). Most of them (n=119, 79%) maintained minimal fear of kidney failure after donation, although 32 (21%) reported an emergence of anxiety about kidney injury or loss at one or more post-donation assessments. Among the 31 (17%) LKDs with moderate to high fear of kidney failure prior to donation, two-thirds (n=20, 65%) reported a similar level of anxiety after donation. In contrast, fear of kidney failure dissipated for 11 (35%) LKDs. Overall, 52 (29%) LKDs reported moderate to high fear of kidney failure at ≥1 post-donation time point. Being single and higher pre-donation fear of kidney failure were significant multivariable predictors of the occurrence of moderate to high fear of kidney failure post-donation (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Number (%) of living kidney donors with clinical change in fear of kidney failure from pre- to post-donation, N = 182

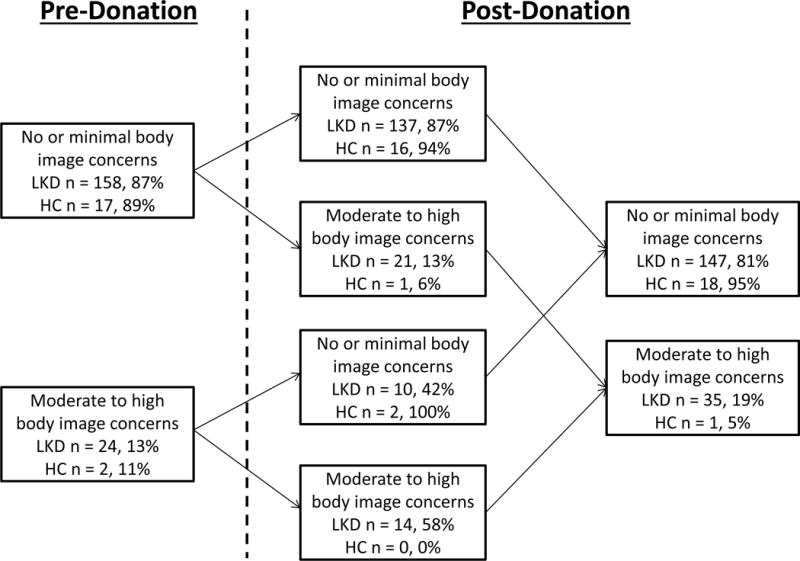

Body image

The majority of LKDs (n=158, 87%) reported no or minimal body image concerns before donation (Figure 3). Most of them (n=137, 87%) maintained a healthy body image after donation, although 21 (13%) reported new-onset moderate to high body image concerns post-donation. Among the 24 (13%) LKDs with moderate to high body image concerns prior to donation, more than half (n=14, 58%) reported similar levels of body image concern after donation. In contrast, 10 (42%) of these LKDs reported no lingering post-donation body image concerns. In total, there were 35 (19%) LKDs who reported moderate to high body image concerns post-donation. HCs reported a similar incidence of body image concerns at baseline assessment and during follow-up (Figure 3). For LKDs, more pre-donation body concerns and perceived pressure to donate were significantly associated with the occurrence of moderate to high body image concerns post-donation in the multivariable model (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Number and percentage of Living Kidney Donors (LKD) and Healthy Controls (HC) with clinical change in body image over time, LKD N = 182 and HC N = 19

Among LKDs, the most commonly expressed issues that persisted over time were being self-conscious about and dissatisfied with one’s appearance and being dissatisfied with one’s body generally. Other body image concerns, such as feeling less physically and sexually attractive, were endorsed by several LKDs early after donation but then returned to pre-donation levels thereafter.

LKD mean satisfaction with scarring score at the 6 month assessment was 3.72 (sd=1.3). Of the 152 LKDs who responded to the question, 126 (83%) reported being moderately to extremely satisfied with the surgical scarring. No pre-donation sociodemographic or clinical characteristics were significantly associated with surgical scarring satisfaction.

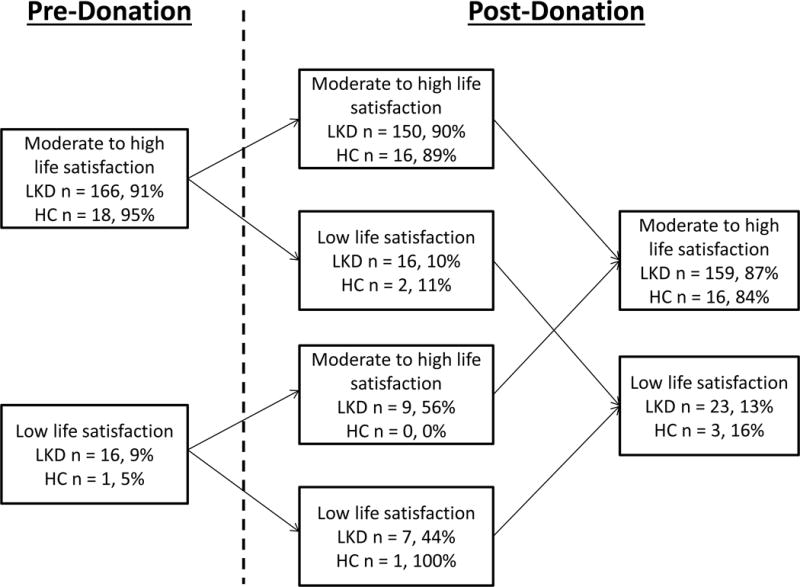

Life satisfaction

The majority of LKDs (n=166, 91%) reported moderate to high life satisfaction before donation (Figure 4). Most of them (n=150, 90%) maintained good life satisfaction levels after donation, although 16 (10%) reported low life satisfaction post-donation. Among the 16 (9%) LKDs with low life satisfaction prior to donation, 7 (44%) reported a similar low level of life satisfaction after donation. In contrast, 9 (56%) of these LKDs reported moderate to high life satisfaction after donation. Overall, there were 23 (13%) LKDs who reported low life satisfaction post-donation. Very similar patterns were seen for the HC cohort (Figure 4). In the LKD multivariable model, minority race and low life satisfaction pre-donation were significantly associated with the occurrence of low life satisfaction post-donation (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Number and percentage of Living Kidney Donors (LKD) and Healthy Controls (HC) with clinical change in life satisfaction over time, LKD N = 182 and HC N = 19

Decision stability

The vast majority of LKDs (n=174, 96%) had no regret about their decision to donate at any point post-donation. Of the 8 LKDs who reported decision regret, six experienced feelings of regret throughout the two-year follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

With few exceptions14–17,19,29–31, most studies examining psychosocial outcomes of LKDs have been retrospective and largely limited to small, single-center cohorts. The KDOC study permitted the prospective examination of living donation outcomes across multiple institutions in the United States. Our current analysis yields four key findings: (1) LKDs did not differ significantly from a small cohort of HCs on psychosocial outcomes at any post-donation time point; (2) the majority of LKDs report no mood disturbance, fear of kidney failure, body image concerns, or life dissatisfaction in the two years post-donation; (3) LKDs presenting for evaluation with mood disturbance, anxiety about future kidney failure, body image concerns, and life dissatisfaction are at highest risk for these adverse outcomes post-donation; and (4) very few LKDs report donation decision regret. Collectively, these findings have implications for the psychosocial assessment of LKDs, education of potential LKDs and informed consent processes, monitoring of psychosocial outcomes post-donation, and future research directions.

In addition to requiring all potential LKDs to undergo psychosocial evaluation, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Organ and Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) require that potential LKDs be informed of certain psychosocial risks, including the risk of anxiety, depression, and body image changes, post-donation (https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1200/optn_policies.pdf). However, the policy is vague, stating only that LKDs should be informed that such risks “…may be temporary or permanent” (p. 183), leaving providers uncertain about the specific nature, incidence, and duration of any psychosocial changes that should be disclosed to potential LKDs. Our data provide some guidance about the pattern and occurrence of such outcomes following donation. For instance, we found that, on average, symptoms of anxiety, depression, poor body image, and life dissatisfaction did not change significantly from pre- to post-donation and that trends in these symptoms over time for LKDs were no different than those of HCs.

The incidence of any new-onset mood disturbance (16%), fear of kidney failure (21%), body image concerns (13%), and life dissatisfaction (10%) during the two-year post-donation period was generally low. Indeed, these findings are consistent with the conclusions reached by others10–15,25,31–33. Dew et al.32, for instance, concluded in their review of the literature that up to 1 in 4 LKDs may experience new-onset psychological distress following donation. However, these new-onset symptoms might not be attributable to donation. Indeed, the incidence of new-onset symptoms in HCs was very similar to that of LKDs. This pattern must be replicated with a larger control sample, of course, but our preliminary findings suggest that rates of mood disturbance, body image concerns, and life dissatisfaction following donation may not be significantly higher than what can be expected in non-donors over time. Until more definitive research is conducted, we agree with the recommendation that transplant programs inform potential LKDs about possible adverse psychosocial outcomes and that these risks be integrated into living donation websites to better inform those seeking donation-related information online.34,35

In a recent review of the prevalence and clinical significance of body image concerns in transplant recipients and living donors, Zimbrean33 reported that body image is infrequently assessed in studies of LKDs and generally not considered problematic when it is examined. In the current study, the majority (83%) was satisfied with the surgical scarring outcome and only a small minority (13%) reported new-onset body image concerns following donation (vs. 6% for HCs). While the incidence of new-onset body image concerns may be slightly higher for LKDs, these findings support Zimbrean’s conclusion that this is not a common issue for former living donors. BMI was not a significant risk factor for body image concerns post-donation, contrary to our initial hypothesis. As programs consider more obese adults for possible kidney donation36,37, some have suggested that obese LKDs warrant more vigilant monitoring for adverse psychosocial outcomes.11,38 Clearly, more research is needed to further delineate the short- and long-term body image concerns in LKDs, particularly since transplant programs are obligated to inform potential donors of this possible adverse outcome.

We found a much higher percentage of KDOC LKDs with high anxiety about future kidney health, compared to our previous survey of 364 former LKDs (29% vs. 13%).21 Time since donation and selection bias may account for these study differences. The assessment of LKDs in the KDOC study was limited to the first 24 months, whereas the median time from donation in our previous study was 71 months. Anxiety about kidney failure may be less frequent and intense as more time passes, especially for former donors who attend annual evaluation and receive reassurance of stable renal function. Also, anxiety about future kidney health may have been under-represented in our earlier study due to the 36% participation rate, and the possibility that those with more anxiety were less likely to respond to the survey.

A central question of our analysis was: What pre-donation factors predict adverse post-donation psychosocial outcomes? Answers to this question may help to identify donors who are at higher risk of poor psychosocial outcomes at the time of their evaluation and thus facilitate more targeted discussion of these risks with the donor candidate. LKDs with more mood disturbance symptoms, higher anxiety about future kidney health, low body image, and low life satisfaction prior to surgery are at highest risk of these same outcomes post-donation. This finding mirrors Wirken et al.’s13 conclusion that LKDs with low psychological functioning pre-donation are those most at risk of impaired long-term psychosocial and quality of life. Donor candidates presenting with these features at time of evaluation should be informed and counseled that kidney donation likely will not ameliorate or reduce symptom burden in these psychosocial domains. Moreover, studies are needed to examine whether pre-donation interventions targeting mood, body image concerns, and low life satisfaction reduce the risk of these adverse psychosocial outcomes following donation.32,39

We did not assess whether new-onset symptoms following donation interfered with life activities or necessitated clinical intervention. Currently, the OPTN requires the assessment of only two psychosocial elements post-donation – employment status and the loss of health or life insurance due to donation. However, as recommended by KDIGO, transplant programs may want to consider integrating a brief psychosocial screening into the post-donation follow-up period to facilitate early identification of emerging psychosocial symptoms in LKDs who may benefit from further assessment or intervention.40 Also, we fully support establishing a scientific registry for LKDs that will expand both the range of outcomes data gathered following donation as well as the assessment period (i.e., beyond two years).41 Such a registry will facilitate more refined examination of the incidence of adverse psychosocial outcomes and their predictors.

There are several notable strengths and limitations of the current analysis. The study benefited from LKD participants from six transplant centers who were generally representative of LKDs in the United States. The majority in our study (94%) completed ≥1 follow-up psychosocial assessment, in addition to the baseline pre-donation assessment. Moreover, we used validated instruments to assess donation outcomes that were recommended for study by former donors. Also, the prospective nature of the study allowed us to examine changes in psychosocial outcomes over time, in comparison to a healthy control sample. Despite these relative strengths, certain limitations should be considered in interpreting findings. Centers participating in the study may not be representative of other programs. More or less stringent psychosocial criteria for the selection of LKDs than those used by the KDOC sites may yield different findings than we observed in this study. Also, the pre-donation psychosocial assessment may not be an accurate representation of symptoms for some LKDs. Although the study outcomes were assessed only after LKDs were approved for donation and participants were informed that research assessments would not be shared with the donor program, some LKDs may have responded to study questionnaires in a more socially desirable manner to avoid any possibility of being excluded from donation due to psychosocial concerns. We examined adverse outcomes over a two-year period only, thus we are unable to comment on more positive psychosocial outcomes or on the long-term psychosocial impact of donation. Finally, while it is novel to include a healthy control group in a prospective cohort study of donation outcomes, our healthy control sample was very small due to very restrictive inclusion/exclusion criteria, thus limiting analytic comparisons to LKDs over time.

In conclusion, this multi-site study provides a prospective analysis of LKDs on psychosocial outcomes of interest to them and the transplant community. Findings suggest generally favorable psychosocial outcomes of LKDs. A small minority experience new-onset negative mood symptoms, anxiety about future kidney health, body image concerns, and life dissatisfaction; however, this pattern might not differ significantly from that of non-donors over a similar time period. Until additional prospective LKD cohort studies, with more healthy controls, can be conducted, we support maintaining the regulatory requirement to inform potential donors about possible adverse psychosocial consequences. Moreover, the development and implementation of a donor registry to capture psychosocial outcomes beyond the mandatory two-year follow-up period in the USA will further refine our understanding of these outcomes over time.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Award No. R01DK085185 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. Preparation of this manuscript was also supported, in part, by the Julie Henry Research Fund and the Center for Transplant Outcomes and Quality Improvement, The Transplant Institute, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the hard work and dedication of the study coordinators and others at the six KDOC transplant centers who assisted in the completion of this project: Aws Aljanabi, Jonathan Berkman, Tracy Brann, Rochelle Byrne, Lauren Finnigan, Krista Garrison, Ariel Hodara, Tun Jie, Scott Johnson, Nicole McGlynn, Maeve Moore, Matthew Paek, Henry Simpson, Carol Stuehm, Denny Tsai, and Carol Weintroub.

Abbreviations

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- KDOC

Kidney Donor Outcomes Cohort

- KTR

Kidney Transplant Recipient

- LDKT

Live Donor Kidney Transplantation

- LKD

Living Kidney Donor

- LOT-R

Life Orientation Test - Revised

- NIDDK

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

References

- 1.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Gustafson SK, Stewart DE, Cherikh WS, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2015 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(Suppl 1):21–116. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodrigue JR, Paek M, Whiting J, Vella J, Garrison K, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA. Trajectories of perceived benefits in living kidney donors: association with donor characteristics and recipient outcomes. Transplantation. 2014;97:762–8. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000437560.23588.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong A, Chapman JR, Wong G, Kanellis J, McCarthy G, Craig JC. The motivations and experiences of living kidney donors: a thematic synthesis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:15–26. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, et al. Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2010;303:959–966. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg AX, Meirambayeva A, Huang A, et al. Cardiovascular disease in kidney donors: Matched cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e1203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mjoen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, et al. Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int. 2013;86:162–167. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311:579–586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reese PP, Bloom RD, Feldman HI, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular disease among older live kidney donors. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1853–1861. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam NN, Lentine KL, Levey AS, Kasiske BL, Garg AX. Long-term medical risks to the living kidney donor. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:411–9. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemens KK, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Parikh CR, et al. Psychosocial health of living kidney donors: a systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2965–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dew M, Myaskovsky L, Steel J, DiMartini A. Managing the psychosocial and financial consequences of living donation. Curr Transplant Rep. 2014;1:24–34. doi: 10.1007/s40472-013-0003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dew MA, Jacobs CL. Psychosocial and socioeconomic issues facing the living kidney donor. Adv Chron Kidney Dis. 2012;19(4):237–243. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wirken L, van Middendorp H, Hooghof CW, Rovers MM, Hoitsma AJ, Hilbrands LB, Evers AW. The course and predictors of health-related quality of life in living kidney donors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:3041–54. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Timmerman L, Timman R, Laging M, Zuidema WC, Beck DK, IJzermans JN, et al. Predicting mental health after living kidney donation: The importance of psychological factors. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:533–54. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmerman L, Laging M, Westerhof GJ, Timman R, Zuidema WC, Beck DK, et al. Mental health among living kidney donors: a prospective comparison with matched controls from the general population. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:508–17. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, et al. Direct and indirect costs following living kidney donation: Findings from the KDOC study. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:869–76. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klarenbach S, Gill JS, Knoll G, Caulfield T, Boudville N, Prasad GV, et al. Economic consequences incurred by living kidney donors: a Canadian multi-center prospective study. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:916–22. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matas AJ, Hays RE, Ibrahim HN. Long-term non-end-stage renal disease risks after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:893–900. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, Katz D, Jones J, Kaplan B, Fleishman A, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA, KDOC Study Group Predonation direct and indirect costs incurred by adults who donated a kidney: Findings from the KDOC Study. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2387–93. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNair D, Lorr M, Droppelman L. Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA, USA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigue JR, Fleishman A, Vishnevsky T, Whiting J, Vella JP, Garrison K, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess fear of kidney failure following living donation. Transpl Int. 2014;27:570–5. doi: 10.1111/tri.12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopwood P, Lee A, Shenton A, Baildam A, Brain A, Lalloo F, Evans G, Howell A. Clinical follow-up after bilateral risk reducing (‘prophylactic’) mastectomy: Mental health and body image outcomes. Psychooncology. 2000;9:462–472. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200011/12)9:6<462::aid-pon485>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Messersmith EE, Gross CR, Beil CA, Gillespie BW, Jacobs C, Taler SJ, et al. Satisfaction with life among living kdney donors: A RELIVE study of long-term donor outcomes. Transplantation. 2014;98:1294–300. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Kosinki M, Dewey JE. How to score version 2 of the SF-36® health survey (standard & acute forms) Lincoln., R.I: QualityMetric; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodrigue JR, Pavlakis M, Egbuna O, Paek M, Waterman AD, Mandelbrot DA. The “House Calls” trial: a randomized controlled trial to reduce racial disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:811–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maple H, Chilcot J, Weinman J, Mamode N. Psychosocial wellbeing after living kidney donation - a longitudinal, prospective study. Transpl Int. doi: 10.1111/tri.12974. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Timmerman L, Zuidema WC, Erdman RAM, et al. Psychologic functioning of unspecified anonymous living kidney donors before and after donation. Transplantation. 2013;95:1369–74. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31828eaf81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janki S, Klop KW, Kimenai HJ, van de Wetering J, Weimar W, Massey EK, et al. LOng-term follow-up after liVE kidney donation (LOVE) study: a longitudinal comparison study protocol. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:14. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0227-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dew MA, Zuckoff A, DiMartini AF, DeVito Dabbs AJ, McNulty ML, Fox KR, et al. Prevention of poor psychosocial outcomes in living organ donors: from description to theory-driven intervention development and initial feasibility testing. Prog Transplant. 2012;22:280–92. doi: 10.7182/pit2012890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimbrean PC. Body image in transplant recipients and living organ donors. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2015;20:198–210. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodrigue JR, Feranil M, Lang J, Fleishman A. Readability, content analysis, and racial/ethnic diversity of online living kidney donation information. Clin Transplant. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13039. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moody EM, Clemens KK, Storsley L, Waterman A, Parikh CR, Garg AX, Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (Donor) Network Improving on-line information for potential living kidney donors. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1062–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Danovitch GM, Johnson SR, Karp SJ, Khwaja K, Hanto DW, Rodrigue JR. The medical evaluation of living kidney donors: a survey of US transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2333–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brar A, Jindal RM, Abbott KC, Hurst FP, Salifu MO. Practice patterns in evaluation of living kidney donors in United Network for Organ Sharing-approved kidney transplant centers. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:466–473. doi: 10.1159/000338450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Groot IB, Stiggelbout AM, van der Boog PJM, et al. Reduced quality of life in living kidney donors: association with fatigue, societal participation and pre-donation variables. Transpl Int. 2012;25:967–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, DeVito Dabbs AJ, Zuckoff A, Tan HP, McNulty ML, et al. Preventive intervention for living donor psychosocial outcomes: feasibility and efficacy in a randomized controlled trial. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2672–84. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lentine KL, Kasiske BL, Levey AS, Adams PL, Alberú J, Bakr MA, et al. Summary of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors. Transplantation. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001770. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kasiske BL, Asrani SK, Dew MA, Henderson ML, Henrich C, Humar A, et al. The Living Donor Collective: A scientific registry for living donors. Am J Transplant. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14365. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]