Abstract

α-Particle irradiation of cancerous tissue is increasingly recognized as a potent therapeutic option. We briefly review the physics, radiobiology, and dosimetry of α-particle emitters, as well as the distinguishing features that make them unique for radiopharmaceutical therapy. We also review the emerging clinical role of α-particle therapy in managing cancer and recent studies on in vitro and preclinical α-particle therapy delivered by antibodies, other small molecules, and nanometer-sized particles. In addition to their unique radiopharmaceutical characteristics, the increased availability and improved radiochemistry of α-particle radionuclides have contributed to the growing recent interest in α-particle radiotherapy. Targeted therapy strategies have presented novel possibilities for the use of α-particles in the treatment of cancer. Clinical experience has already demonstrated the safe and effective use of α-particle emitters as potent tumor-selective drugs for the treatment of leukemia and metastatic disease.

Keywords: α-particle, actinium-225, radium-223, targeted therapy, radioimmunotherapy, nanoparticles

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer therapy using α-particle emitters may be among the first proposed nonsurgical treatments of cancer. It can be traced to the discoveries of Marie and Pierre Curie in the late 1800s and to a publication and correspondence by Alexander Graham Bell circa 1903 (1). The ensuing quackery involving bottled radium solutions (e.g., Radithor) as the cure for almost any ailment (2), as well as associated carcinogenicity and death resulting from the casual use of radium for watch dials (3) and of thorium as a contrast agent in radiographic examinations (4), placed a stigma on the use of α-particle emitters that, to a substantial extent, persists today.

In contrast to this early experience, clinical trial investigations of α-particle emitters for cancer therapy show excellent potential as safe and highly effective cancer therapies in patients with few to no remaining therapeutic options (5, 6). The cancer therapy community as well as the pharmaceutical industry have taken note of these and other, more recent demonstrations of the potential efficacy of α-particle emitters (7, 8). Since unconjugated antibodies, antibody–drug conjugates, and signaling pathway inhibitors have made their way through the clinical trial pipeline with somewhat mixed results, α-particle emitters are the next potential antitumor agent to “load” onto an already-established and largely antibody-based drug delivery platform.

The development and use of α-particle-emitter therapeutics require an understanding of the physics, radiobiology, and dosimetry of these agents. The fundamental aspects of each of these areas have been extensively covered elsewhere (9). This review briefly summarizes these important aspects of α-particle-emitting radionuclides and provides an update on recent developments. We also include an overview of recent preclinical and clinical studies. This review ends by highlighting the intrinsic advantages of radiopharmaceutical therapy as a treatment modality. Specifically, this treatment approach could incorporate treatment planning methods (i.e., precision medicine) to reduce the scope of human experimentation by taking advantage of the ability to image and calculate absorbed doses to dose-limiting organs and tumors—the former to identify the treatment and escalation schedule in phase I escalation studies and the latter to assess futility.

Although cancer therapy with α-particle emitters appears complex, the essence of this treatment approach is delivery of a higher level of α-particle radiation to tumor than to normal tissues. Key questions concerning successful implementation of α-radiopharmaceutical therapy are where within the body the agent goes and how long it stays there. These questions are simpler to answer than those posed by biologic therapy or signaling pathway inhibition therapy, which require a fundamental and mechanistic understanding of what are now known to be highly redundant and complex signaling pathways that trigger and preserve a cell’s phenotypical cancerous behavior. Key questions in this context are whether the drug inhibits the selected pathway, whether inhibition of this pathway leads to treatment efficacy, and what else the drug does.

2. BRIEF REVIEW OF THE PHYSICS, RADIOBIOLOGY, AND DOSIMETRY OF α-PARTICLES

α-Particles are helium nuclei. a-Particle decay results in the loss of two neutrons and two protons:

After α-particle decay, the atomic weight (A) and atomic number (Z ) of the daughter element, Y, are lower by four and two, respectively, than those of the parent element, X. Q is the excess energy resulting from the transformation of X to Y. This energy is shared as kinetic energy by Y and the α-particle. For α-particle-emitting radionuclides of potential use in radiopharmaceutical therapy, the kinetic energy of the emitted α-particles is in the range of 4 to 9 MeV, approximately 1,000-fold greater than the typical β-particle energies of radionuclides that have been considered for radiopharmaceutical therapy. Because of the much higher mass of α-particles compared with β-particles, however, the range of α-particles in tissue is substantially shorter (50 to 100 μm) than that of β-particles (0.5 to 5 mm). Accordingly, α-particles deposit 400 to 500 times more energy per unit path length traveled than β-particles.

The radiobiology of α-particles was established in a series of seminal studies performed in the 1960s (10–17). High linear energy transfer (LET) leads to largely irreparable DNA double-strand break damage such that individual α-particle interactions with DNA yield a high probability of cell lethality. In contrast, in DNA damage induced by low LET, such as β-particles (and photons), cell death requires the accumulation of many (thousands) of DNA ionization events, or “hits,” to overcome the cell’s DNA repair machinery.

Because α-particle-induced cell death does not depend on the accumulation of α-particle–DNA hits, modulators of DNA repair that reduce or prevent the accumulation of a lethal number of hits do not affect α-particle-induced cell death. Accordingly, hypoxic cells are as radiosensitive to α-particle radiation as well-oxygenated cells. The level of cell death does not depend on the α-particle dose rate; the radiation damage caused by α-particles is considered impervious to conventional cellular resistance mechanisms such as effusion pumps, signaling pathway redundancy, and cell cycle modulation (e.g., cell dormancy, G1/G0 or G2/M block) (15, 18–31).

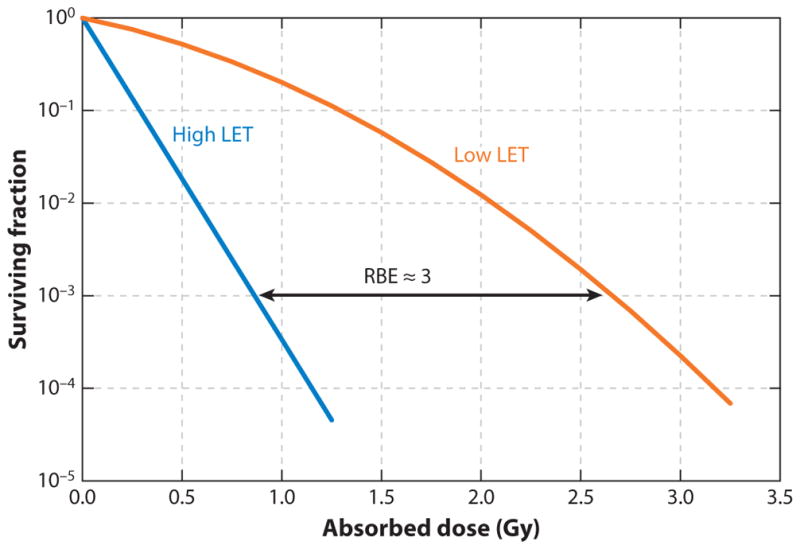

Another important manifestation of the high LET emission associated with α-particle tracks is that a given absorbed dose of α-particle radiation causes a greater biological response in tissue—normal organ toxicity or tumor cell death—than the same absorbed dose of β- or γ particle radiation. The absorbed dose is the energy absorbed in a given volume divided by the mass of the volume. The greater biological response of α-particles per unit absorbed dose is quantified as their relative biological effectiveness (RBE), which is defined relative to a reference radiation value and a biological endpoint. It is the ratio of a reference radiation–absorbed dose to the α-particle radiation–absorbed dose required to achieve a particular endpoint (Figure 1). The reference radiation has typically been a beam of cobalt-57 photons. Historically, the RBE has been measured for cells in cell culture using clonogen formation assays and a cell survival endpoint. The RBE under these circumstances ranges from three to seven. Higher values (RBE = 21) may be achieved if cell signaling pathways associated with DNA double-strand break repair are inhibited (32). Because the RBE may be thought of as a ratio of radiosensitivities, increases in the RBE require that the sensitivity to high LET radiation increase while the sensitivity to low LET radiation either remain unchanged or decrease.

Figure 1.

Cell survival curves as a function of absorbed dose for high and low linear energy transfer (LET) emitters. Abbreviation: RBE, relative biological effectiveness.

As noted above, the RBE for α-particles is obtained by calculating the α-particle and β-particle (or photon) absorbed doses required to obtain a particular tissue response. Dosimetry methods for radionuclides that emit β-particles or photons are already established (33). These methods were initially developed to estimate the radiation risk of radiolabeled diagnostic imaging agents; accordingly, they provide estimates of the mean absorbed dose for normal organ volumes defined by reference anatomies, and not for individual patients. Dosimetry methods for therapy and, in particular, therapy with α-particle emitters require consideration of tissue subregions that are defined, in part, by the distribution of the agent at the millimeter scale for β-particle emitters and at the submillimeter scale for α-particle emitters (34, 35). To relate the absorbed dose from α-particle-emitting radionuclides, the RBE of α-particles must be used to account for their greater biological efficacy per unit absorbed dose.

2.1. Preclinical and Clinical Studies

A comprehensive review of both preclinical and clinical α-particle emitter studies was published as a monograph by the Committee on Medical Internal Radiation Dose in 2015 (36). Table 1 lists the α-particle emitters currently being investigated for radiopharmaceutical therapy, their half-lives, and the energy emitted by all daughters in the decay chain of the radionuclide. The table shows that thorium-227 (227Th) would deliver an approximately four-times-greater absorbed dose to a tumor or normal organ if all of the α-particle energy were absorbed in these tissues. The table also shows the percentage of the total emitted energy that would be retained in a particular tissue if the agent were localized to the tissue very rapidly (relative to the half-life of each ra-dionuclide) and then cleared with the indicated half-life. As expected, long-lived radionuclides are much more dependent on the biological clearance kinetics of the agent than short-lived radionuclides. Accordingly, if tumor retention of the agent were short-lived, then a short-lived α-particle emitter would be more effective under a rapid targeting scenario. The opposite would be true for short-lived retention in a normal tissue; a long-lived α-particle emitter would yield less toxicity.

Table 1.

α-Particle-emitting radionuclides for radiopharmaceutical therapy

| α-Particle-emitting radionuclide | Half-lifea | Totalb α-particle energy emitted per disintegration × 10−12 J/(Bq · s) | Percent of total emitted energy retained if biological half-life in tissue is:c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 h | 1 day | 10 days | |||

| Actinium-225 (225Ac) | 10.0 days | 4.42 | 1.0% | 9.1% | 50.0% |

| Astatine-211 (211At) | 7.214 h | 1.09 | 25.0% | 76.9% | 97.1% |

| Bismuth-212 (212Bi) | 60.55 min | 1.25 | 98.3% | 99.8% | 100.0% |

| Bismuth-213 (213Bi) | 45.59 min | 1.33 | 98.7% | 99.9% | 100.0% |

| Lead-212 (212Pb)/(212Bi) | 10.64 h | 1.25 | 18.4% | 69.3% | 95.8% |

| Radium-223 (223Ra) | 11.43 days | 4.23 | 98.3% | 99.8% | 100.0% |

| Thorium-227 (227Th) | 18.68 days | 5.28 | 0.9% | 8.0% | 46.7% |

Source: http://www.nndc.bnl.gov.

Calculated as the weighted sum of α-particle energy emitted by all of the α-particle emissions included in the decay scheme, including α-particles emitted by the daughters.

Obtained as , where Tp and Tb are the physical half-life of the radionuclide and the biological half-life of the radiopharmaceutical, respectively.

A very brief discussion of preclinical and clinical studies for α-particle emitters follows. In Section 2, we present a more detailed review of the clinical applications to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and prostate cancer.

Actinium-225 (225Ac) was first described as a proposed antibody-conjugated therapeutic in 1993 (36). 225Ac-conjugated anti-CD33 antibody was evaluated in a phase I clinical trial reported in 2006 (37). The maximum tolerated dose obtained was 111 kBq per 0.020 mg/kg. Preclinical and clinical investigations of 225Ac with other targeting agents are ongoing. In particular, 225Ac-labeled low-molecular-weight anti–prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) agents have shown dramatic reduction of metastatic foci in patients with prostate cancer (38). The effect of this initial result on long-term survival has not yet been examined, however.

Astatine-211 (211At) is probably the most-studied α-particle emitter. It was first produced in 1940 at the Berkeley cyclotron (39). It is a halogen with some metalloid properties; its atomic number of 85 places it under iodine on the periodic table. The higher potency in vitro, stability in vivo, and therapeutic efficacy of a very wide variety of 211At compounds have been investigated. Most of this research has focused on antibodies (40–46). 211At has also been conjugated to low-molecular-weight PSMA–targeting ligands (47) and a neurokin 1 receptor–targeting ligand that is overexpressed on glioma (48). Antibodies targeting the extracellular matrix protein tenascin and a mucin glycoprotein, MUC1, which are overexpressed in brain and ovarian cancer, respectively, have been investigated in human trials (49, 50).

Like 211At, bismuth-212 (212Bi) was one of the first α-particle emitters to be studied. Unlike 211At, however, 212Bi is a naturally occurring radionuclide. It may be obtained from the thorium-232 decay chain. Its efficacy as a cancer therapeutic was first tested, in vitro, by conjugating it to an antibody against the human interleukin-2 receptor (25). Intraperitoneal injection of 212Bi-labeled immunoglobulin M antibody led to the elimination of ascites and long-term survival in mice (27). Intravenous administration of 212Bi-labeled antibody showed that the radiometal chelate conjugation method was unstable in the circulation and led to high concentrations of 212Bi in the kidneys. A concerted effort to identify more stable chelates identified the CHXA-DTPA (trans-cyclohexyldiethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid) chelate as the most stable antibody–radiometal conjugate in vivo (51, 52). This chelate conjugation method has been used in several preclinical studies focused primarily on targeting leukemia (53, 54), ovarian cancer (55), and bone metastases (56)—scenarios in which targeting is rapid and compatible with the short, 1-h half-life of 212Bi. Human studies using 212Bi-conjugated agents have not been performed.

The first clinical trial of an α-particle emitter for cancer therapy used bismuth-213 (213Bi) conjugated to an anti-CD33 antibody in patients with leukemia (57). 213Bi has subsequently been used in Europe to treat patients under compassionate-use provisions that do not require regulatory approval (58–60).

To reflect the two fundamentally different approaches to its use, 212Bi is listed twice in Table 1. The first entry and discussion correspond to direct radiolabeling of this α-particle emitter to targeting molecules. The second entry relates to the conjugation of its parent, lead-212 (212Pb), which decays with a 10.6-h half-life by β-particle emission to 212Bi. The advantage of this approach is that it effectively overcomes the short, 1-h half-life of 212Bi, thereby enabling the delivery of α-particles from 212Bi to targets that are not rapidly accessible to antibodies and other targeting vehicles. Preclinical survival studies have shown that colloidal and targeting-vehicle-conjugated use of 212Pb to deliver 212Bi improves survival. Several early studies were associated with significant toxicity resulting from the release of free 212Bi following β-particle decay of 212Pb. In 2000, a bifunctional chelate became available that better retained 212Bi within the chelate (61). Availability of this construct enabled human investigations of a 212Pb-conjugated anti-HER2/neu antibody, trastuzumab, in patients with HER2/neu+ abdominal tumors (62, 63).

Radium-223, in the form of radium-223 chloride, (223 RaCl2; trade name Xofigo® ) is the first α-particle-emitter-based radiopharmaceutical therapeutic to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It was approved in 2013, following a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in prostate cancer patients with progressive, castration-resistant disease (5). The currently available and expanding list of treatment options for this population of patients with late-stage prostate cancer (64) was not available at the time. Optimal sequencing and combination of this agent with currently available therapies are a subject of ongoing investigation (65).

Efforts to conjugate 223Ra to targeting agents have not been successful. 227Th, the α-particle-emitting parent of 223Ra, can be conjugated to antibodies and other targeting agents (66). 227Th has a half-life of 18.7 days, longer than any of the other α-particle emitters being considered for cancer therapy. Its first daughter, 223Ra, also has a long half-life (11.4 days), and its biodistribution is that of free radium rather than of the targeting agent. By contrast, the safety and toxicity of 223Ra in humans are well established. Accordingly, targeting agents radiolabeled with 227Th have been the subject of intensive preclinical investigations (67–70). The results of these preclinical studies have consistently shown significantly improved survival with tolerable toxicity.

2.2. Distinguishing Features of Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

A therapeutic agent that incorporates delivery of a radionuclide provides a degree of freedom for therapy optimization that is not available in conventional treatment modalities. As Table 1 shows, each radionuclide is characterized by a half-life, which from the perspective of pharmacodynamics, places a time dependence on drug activity. If, for example, a 213Bi-labeled radiopharmaceutical therapy requires 24 h to reach a dose-limiting organ, then a negligible fraction of the α-particle energy will be delivered to the dose-limiting organ. This will reduce toxicity. By contrast, if the time to localize to the tumor is equally prolonged, efficacy will be negligible. Such considerations are relevant to short-lived radionuclides. As the radionuclide half-life increases, efficacy and toxicity show a greater dependence on the agent pharmacokinetics, as is the case for conventional therapeutics.

Synthetic lethality has been highlighted as a promising approach to enhance the functional targeting of signaling pathway inhibitors (71). The essence of the synthetic lethality concept is as follows: Because pathway redundancy in tumor cells is reduced due to mutations, tumor cells are more susceptible to a particular pathway inhibitor than are normal tissues, causing reduced toxicity in normal organs. The prototypical example of synthetic lethality involves inhibition of DNA repair pathways. From this perspective one may envision a combination of α-particle-emitter-based radiopharmaceutical therapy with a DNA double-strand break repair inhibitor. Targeting of the α-particle-emitter-labeled agent to cancer cells confers a first-order level of synthetic lethality; the high LET radiation and increased propensity for double-strand break damage, coupled with a double-strand break repair inhibitor, confer another layer of synthetic lethality (32).

The optimal dose level for a new low-molecular-weight pathway inhibitor, chemotherapeutic agent, or antibody is usually obtained from a phase I dose escalation trial followed by one or more multiarm clinical trials—typically guided by preclinical findings and, more recently, by biomarker studies. The mechanism of action depends on the agent. In contrast, almost all radiopharmaceutical therapeutics include emissions that may be imaged by a nuclear medicine imaging modality. This makes it possible to obtain tumor and normal tissue pharmacokinetics to estimate the absorbed dose. Because the mechanism of action for all radiopharmaceuticals is ionizing radiation–induced DNA damage–associated cell death, the extensive experience of dose response from radiation therapy may be used to select administered activities that yield normal organ and tumor absorbed doses that are nontoxic but within the range of tumor doses deemed potentially effective. Trial designs that incorporate dosimetry in this way will reduce the number of patients required for an escalation study as well as the time required to assess efficacy and toxicity. In this context, imaging, pharmacokinetic measurements, and dosimetry become part of a precision medicine–based treatment planning paradigm that delivers the right dose to the right patient.

3. THE EMERGING CLINICAL ROLE OF α-PARTICLE THERAPY IN MANAGING CANCER

α-Particle irradiation of cancerous tissue is increasingly being recognized as a potent therapeutic option. Two diseases in particular have been extensively investigated to explore the clinical potential of α-particle therapy. Treatment of AML with the α-particle-emitting drugs [213Bi]lintuzumab and [225Ac]lintuzumab is a safe and effective means of managing the disease in patients for whom intensive chemotherapy regimens are no longer an option. Both drugs are monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting CD33 expression, and their α-particle payloads reduce bone marrow blasts in a dose-dependent fashion with minimal off-target toxicity. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer is being treated with [225Ac]PSMA-617, a small-molecule drug targeting PSMA, and with the FDA-approved 223RaCl2 (Xofigo), targeting osseous disease. High-energy α-particle irradiation of prostate cancer has proven very effective in reducing tumor burden and prostate-specific antigen levels and in relieving pain.

3.1. Candidate Radionuclides for Cancer Therapy

Several suitable candidate radionuclides are presently under consideration as effectors of α-particle treatment (72). In this section, we focus on α-particle emitters that have had major roles in clinical applications to treat AML and prostate cancer.

225Ac (half-life, 10 days) decay produces 213Bi (half-life, 46 min) along with four net α-particles in a cascade to stable bismuth-209. The 213Bi radionuclide can be isolated using robust generator technology (73) to prepare α-particle drugs that are potent and specific but logistically infeasible for widespread clinical use due to their very brief half-life. However, the parent 225Ac radionuclide is an excellent candidate for use in cancer therapy; it is a long-lived isotope that can be radiolabeled onto any delivery platform (i.e., antibody, nanoparticle, small molecule, peptide) and shipped virtually anywhere for medical use. Internalizing delivery platforms deploy the energy of all of the 225Ac decay progeny toward irradiating disease and limiting off-target daughter toxicity. Selection of a thermodynamically stable chelate agent is required to bind the 225Ac so that it can be delivered to the cancer target and internalized (28, 74).

223Ra (half-life, 11.4 days) can be obtained from generator systems by use of an 227Ac parent (half-life, 21.8 years) (75, 76) and from the process by-products of uranium mills (72). 223Ra has several decay progeny and yields four net α-particles in its transition to stable lead-207. The delivery of radium using chelating agents presented a difficult problem, but the issue was solved by taking advantage of the known avidity of bone tissue for ionic radium. FDA approval of 223RaCl2 provided the first α-particle therapeutic used for palliative care and for the treatment of osseous disease.

3.2. Matching the Delivery Vehicle with the Disease Target

A key consideration in designing α-particle-emitting drugs for use in humans is selecting a molecular platform to convey the radionuclide to the target cell. mAbs have attracted much attention due to the many unique biological features that they impart. Typically, intact mAbs are approximately 150 kD and can be decorated with several chelate moieties. The chelate chosen to bind the radionuclide is an essential element in the design of these drugs because the thermodynamic stability of the bound radionuclide must ensure that the complex remains intact until delivered. Antigen specificity and binding avidity are also crucial for biologically effective agents, as is the ability to avoid binding off-target and producing untoward toxicity to normal tissue. Biological half-life depends on the time and amount of the drug (i.e., radionuclide) in blood and also dictates dosing. For example, lintuzumab is a humanized mAb directed against the CD33 surface epitope expressed on myeloid cells. Furthermore, once formed, the lintuzumab:CD33 immunocomplex rapidly internalizes and carries any α-particle-emitting cargo inside the cell. This internalization process conveys a tremendous radiobiological advantage—first, because the probability of α-particle decay in the cytoplasm is unity and, second, because any progeny of the parent nuclide is sequestered within the cell, also ensuring that their α-particle decays occur within the cellular confines (28, 74).

Peptides and small molecules have also been investigated for radionuclide delivery platforms. Given the large difference in molecular weight between peptides/small molecules and antibodies, the former often clear more rapidly from the blood compartment, and this quick elimination can be beneficial if bone marrow toxicity is an issue with a longer-circulating, larger antibody. Furthermore, small-molecule/peptide species may have greater access to zones in tumors (and sometimes normal tissue) where the antibody is diffusion limited. Pharmacokinetic data in animal models and dosimetric projections are required to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of large versus small molecules.

Cationic 223Ra is an example of the simplest molecular configuration for radionuclide delivery in vivo. This ionic element is a bone-seeking agent that resembles calcium, another alkaline earth metal. Suitable chelating agents for 223Ra have yet to be identified, rendering attachment to either a small molecule or antibody problematic. The characteristic radioradium pharmacokinetic profile is known and has been utilized to treat ankylosing spondylitis with 224Ra (77). Unfortunately, this chemical mode of delivery severely limits the use of 223Ra to bone disease and bone cancer, thereby eliminating therapeutic applications directed against other cancers.

3.3. Clinical Use of α-Particles

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has been pioneering the use of α-particle-emitting drugs for two decades. Proof of concept was established for targeted α-particle therapy in humans in a phase I clinical trial in which the antileukemic effect of [213Bi]lintuzumab (note that lintuzumab was originally named HuM195) was demonstrated in patients with a relatively high tumor burden (30, 78–80). Because of the large tumor burden in AML, the phase I/II study used a regimen wherein cytarabine was administered prior to the [213Bi]lintuzumab to cytoreduce before commencing α-particle therapy. These studies showed safe, potent, and specific treatment outcomes for α-particle-emitting antibody constructs in vivo. These positive proof-of-concept trials with the first-generation 213Bi drug led to the first clinical trial of the longer-lived and more potent 225Ac in humans using the next generation [225Ac]lintuzumab construct (6, 37, 81–83). This immunotherapeutic drug was safe and effective in the treatment of leukemia. In summary, 18 patients were treated and evaluated [relapsed AML (n = 11) or primary refractory AML (n = 7)]. Dose escalation (0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 μCi/kg) identified a maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of 3 μCi/kg. Toxicities at the MTD included grade 4 neutropenia (n = 3), grade 4 thrombocytopenia (n = 3), and grade 3/4 bacteremia (n = 1) (note that lintuzumab targets CD33 expressed on hematopoietic tissue and cancer). No evidence of radiation nephritis was observed at 1–24-month follow-up (median, 2 months) at any dose level. Antileukemic activity was observed across all dose levels: Peripheral blasts were eliminated in 10 of 16 patients (63%) at doses of 1 μCi/kg or more; bone marrow blasts were reduced in 10 of 15 patients (67%); 8 patients (53%) had bone marrow blast reductions of 50% or more; and 3 patients had bone marrow blasts of 5% or less. [225Ac]lintuzumab was safe at doses of 3 μCi/kg or less and exhibited antileukemic activity across all dose levels.

The positive results of this initial trial led to a multicenter, phase I dose escalation trial to determine the MTD, toxicity, and biological activity of fractionated-dose [225Ac]lintuzumab given in combination with low-dose cytarabine (LDAC). Older patients (≥60 years) with untreated AML and poor prognostic factors were eligible for enrollment. Patients received up to 12 cycles of LDAC (20 mg twice daily for 10 days) every 4–6 weeks. Each patient received two doses of [225Ac]lintuzumab, administered approximately 1 week apart during the initial LDAC treatment cycle. [225Ac]lintuzumab doses were 0.5 (n = 3) or 1 (n = 6) μCi/kg/fraction for a total administered activity that ranged from 67 to 200 μCi of 225Ac. Grade 4 thrombocytopenia with bone marrow aplasia persisting more than 6 weeks was the only dose-limiting toxicity that was observed in one patient who received 1 μCi/kg/fraction. Hematologic toxicities included grade 4 neutropenia (n = 1) and thrombocytopenia (n = 3); grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities included febrile neutropenia (n = 6), pneumonia (n = 2), bacteremia (n = 1), cellulitis (n = 1), transient increase in creatinine (n = 1), hypokalemia (n = 1), and generalized weakness (n = 1). Antileukemic effects included bone marrow blast reduction in five of seven patients (71%), and mean blast reduction was 61% evaluated after LDAC cycle 1. Three of the seven patients (43%) had bone marrow blast reductions of 50% or more. Median progression-free survival was 2.5 months (range, 1.7–15.7 months and higher). Median overall survival (OS) from study entry was 5.4 months (range, 2.2–24 months). For the seven patients with prior myelodysplastic syndrome, median OS was 9.1 months (range, 2.3–24 months). To date, fractionated-dose [225Ac]lintuzumab in combination with LDAC has been feasible and safe and has shown antileukemic activity.

Xofigo is an FDA-approved 223RaCl2 drug that targets osseous tissue undergoing extensive remodeling as a consequence of metastatic prostate cancer. The dose regimen of Xofigo is six injections of 50 kBq (1.35 microcurie) per kilogram body weight, administered at 4-week intervals. Reported major adverse effects are hematologic toxicities including thrombocytopenia and neutropenia (76). With the use of this drug, which was initially designed as a palliative α-particle-emitting agent intended to replace β-particle emitters such as phosphorus-32, strontium-89, and samarium-153, other favorable treatment outcomes were observed. In addition to improving quality of life, there were positive biochemical responses such as decreased alkaline phosphatase and improved survival. 223Ra is a bone-seeking agent (note that 40–60% of the administered dose is accumulated in the skeleton) that delivers sufficient energy to diseased bone tissue and is capable of favorably influencing the disease and providing pain relief (76). Unfortunately, this indication limits the use of 223Ra to bone and bone cancer and eliminates applications for therapeutic use in other cancers. Perhaps applications in combination with other agents and at earlier times could broaden the use of this drug.

PSMA has long been studied as a target for radionuclides to irradiate prostate cancer. Recently, the Heidelberg group (7) commenced treating men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with an 225Ac-labeled small-molecule anti-PSMA drug. In retrospective studies, these authors reported their findings in two patients with complete response to [225Ac]PSMA-617 therapy at a dose of 100 kBq per kilogram body weight [note that this 2.7 μCi/kg dose parallels the [225Ac]lintuzumab doses (≤3 μCi/kg) that exhibited antileukemic activity]. They followed PSMA response and hematologic toxicity at monthly intervals. Both patients experienced a decline in prostate-specific antigen to below measurable levels as well as complete response on imaging with a [68Ga]PSMA-11 surrogate reporter. Severe xerostomia was observed and attributed to accumulation of drug in the salivary tissue. No relevant hematologic, renal, or hepatic toxicities were reported, but these assessments would benefit from prospective clinical evaluation. Both patients had undergone extensive pretreatment to manage their disease and were offered [225Ac]PSMA-617 as salvage therapy in accordance with paragraph 37 of the updated Declaration of Helsinki, “Unproven Interventions in Clinical Practice,” and in accordance with German regulations.

3.4. Future Directions

Interest in α-particle radionuclide therapy has increased due to greater availability and improved radiochemistry of these nuclides. Targeted therapy strategies have presented novel possibilities for their use in the treatment of cancer. α-Particles offer key advantages over β-particles and Auger particles because of the combination of their high LET and limited range in tissue. LET is on the order of 100 keV/μm and can produce substantially more lethal double-strand DNA breaks per α-particle track than β-particles. The relatively short α-particle tracks have a limited range in tissue and are on the order of a few cell diameters, thereby confining cytotoxic effects to a relatively small area. The number of particle track transversals through a tumor cell required to kill the cell is considerably lower for α-particles compared with β-particles, and a single α-particle transversal can kill a cell (28). This greater biological effectiveness is independent of oxygen concentration, dose rate, and cell cycle station.

Key to harnessing the therapeutic potential of 225Ac is control of the fate of the parent and progeny radionuclides, a strategy that has been utilized with both [225Ac]lintuzumab and [225Ac]PSMA-617 to treat AML and prostate cancer, respectively. Both drugs utilize the tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) chelate moiety as a chelating agent that forms stable 225Ac complexes in vivo. In these cases, the targeting platforms are quite different but the pharmacokinetic profile of the parent nuclide is managed by the DOTA chelate. Each drug platform also internalizes upon binding to its target and thus allows the progeny to decay within the cell, contributing to cytotoxic radiobiological effects. This nanogenerator approach has altered the multiple α-particle decay paradigm and has unmistakably demonstrated the ability to safely and efficaciously deploy 225Ac as an extraordinarily potent tumor-selective drug to treat leukemias and metastatic disease.

4. PRECLINICAL α-PARTICLE THERAPY DELIVERED BY NANOMETER-SIZED PARTICLES

Among the many forms of radiation delivery (e.g., radiolabeled antibodies, antibody fragments), nanometer-sized particles inevitably result in altered biodistributions and pharmacokinetics, which—depending on the disease topology and morphology—may provide some advantages. The main categories of materials that have been reported for the delivery of α-particle emitters include self-assembled vesicular structures (liposomes, polymersomes), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and inorganic nanoparticles (layered nanoparticles and zeolites).

In this section, we discuss the main directions of reported approaches with certain properties, including (a) stable retention of radioactive cargo, (b) high specific loading of radioactivity (relative to immunoglobulin G, for example), and (c) addition of a targeting functionality to enable selectivity in the delivery of the radionuclides.

4.1. Encapsulation of α-Particle Emitters by Self-Assembled Vesicles

In the early 2000s, the first studies on encapsulation of liposomes with α-particle emitters were reported. These studies were preceded by reports of liposome radiolabeling with γ-particle emitters using ionophore-mediated loading (84). In 2004, Henriksen et al. (85) discussed the active loading of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)ylated, DOTA-containing liposomes with 223Ra and 228Ac using the calcium ionophore A23187, and demonstrated high radiolabeling efficiencies (>78% for 223Ra, depending on the loading temperature and incubation length, and 61 ± 8% for 228Ac) accompanied by stable retention of the parent nuclei (>95%) for both emitters following incubation in human serum–containing media for 24 h. The same year, Sofou et al. (86) demonstrated stable retention of 225Ac (the parent nuclide) by liposomes (>88% after 30 days) following passive encapsulation. The potential usefulness of 225Ac-loaded liposomes was subsequently supported by Chang et al. (87), who demonstrated greater loading efficiencies—as high as 73 ± 9% of introduced radioactivity—using ionophore-mediated loading of liposomes with A23187 or oxine. These liposomes, by being in the gel phase at working temperatures, demonstrated stable retention of radioactivity, in some cases as high as 81 ± 7% after 30 days.

4.2. Retention of Actinium-225’s Radioactive Daughters by Self-Assembled Vesicles

Stable retention of the radionuclide 225Ac was less challenging than the retention of its radioactive daughters. Daughter retention studies were motivated by the observed renal toxicities in animal models, usually associated with nonretained 213Bi during circulation of 225Ac-labeled antibodies. Interestingly, these toxicities were later reported to be addressed by administration of diuretics, although in humans the bone marrow may be the dose-limiting organ (88). In a study involving shell-like structures, Sofou et al. (86) demonstrated that, as with liposomes, shell diameter has an effect on daughter retention during recoil, taking into account the daughters’ recoil lengths. For this geometry, the calculation assumed uniform distributions within the encapsulated aqueous phase of the radioactive parent and daughters, upon completion of their recoil trajectory. The lipid bilayer forming the shell was predicted not to retain and/or attenuate the daughters during their recoil, but rather to act as a diffusion barrier to the daughters upon completion of their recoil trajectory. This calculation predicted that for more than 60% retention of the last radioactive daughter, 213Bi, particle sizes larger than 800 nm in diameter would be needed. This calculation assumed uniform distribution of the parent and daughter nuclides within the encapsulated aqueous phase of the particles. For phospholipid vesicles, the actual size–daughter retention relation was dominated by the preferential association of the radioactive daughters with the polar lipid headgroups. In that case, the probability of loss of the subsequently generated daughter(s) was greatest (50%) independent of the vesicle size. The actual retention of 213Bi was limited to less than 10% for 800-nm-diameter vesicles. The formation of multivesicular liposomes (i.e., large lipo-somes with smaller lipid vesicles encapsulated within)—aiming to increase the daughter-attracting phospholipid headgroup region in the internal volume of liposomes—showed improved retention of 213Bi. However, multivesicular liposomes, due to the complexity of their preparation, are not a practical approach (89). In a later study, Wang et al. (90) revisited the issue of daughter retention using vesicles formed by self-assembled polymeric amphiphiles (polymersomes) and demonstrated improved retention of 213Bi (53 ± 4% by 800-nm-diameter vesicles, comparable to the theoretical value); the improved 213Bi retention was probably due to diminished interactions between the daughters and the polar surface of the constitutive polymers. The loading of 225Ac by polymersomes was stable (only 7% of the parent radionuclide was released after 30 days).

Given our current understanding of interfacial interactions between biomaterials and the biological milieu, large (~800-nm-diameter) particles—such as the ones suggested above, which are necessary for daughter retention—can be envisioned to be administered intraperitoneally (91) to be utilized mostly as drug depots for both long(er) retention by and higher delivered doses to the peritoneal cavity, or to be injected upstream of target organs, such as in hepatic embolization strategies previously reported for radiolabeled colloids (92).

Retention of radioactive daughters should be critical for carriers with blood circulation times comparable to or longer than the decay kinetics of 225Ac determining the time-integrated activity in the blood and, subsequently, to the kidneys due to released (renal-attractant) 213Bi during circulation. However, most nanometer-sized carriers exhibit fast blood clearance rates relative both to 225Ac decay and to the clearance rates observed for mAbs. For comparison to the latter, the difference could be on the order of 10–90-times-faster clearance for nanoparticles [in humans, the clearance half-lives are 2–3 days for nanoparticles (liposomes) (93) versus ~12 days for antibodies (94); in mice the clearance half-lives are 2–3 h for nanoparticles (95, 96) versus several days for antibodies (97, 98)]. This comparison suggests that daughter retention during the relatively short blood circulation times of carrier nanoparticles may not be critical for renal toxicities, because most decays would occur later in time upon completion of blood clearance. The importance of short circulation times for potentially relaxing the requirements of daughter retention by 225Ac carriers during circulation is also supported by a recent report of an 225Ac-DOTA-radiolabeled anti-PD-L1 antibody that, upon intravenous administration in mice, exhibited clearance dominated by an unusually fast rapid phase (7 to 14 h) (99). As a result, at certain antibody doses, 225Ac delivery by these antibodies exhibited tumor-to-blood ratios of time-integrated activities greater than 2.5. For comparison, the corresponding ratios of time-integrated activities for the faster decaying 211At (half-life, 7.2 h) delivered by the same antibody were calculated to be approximately only 0.5 because, in this case, the kinetics of blood clearance and radioactive decays were comparable and most decays occurred during blood circulation. Additionally, and importantly, upon tumor (or off-target organ) uptake, the generated radioactive daughters are highly likely to associate with nearby cells (28) and not to escape from the site of the parent nucleus.

4.3. Retention of Actinium-225’s Radioactive Daughters by Solid Inorganic Nanoparticles

A different strategy to retain the radioactive daughters of 225Ac was developed by the Mirzadeh group (100) by using lanthanide nanoparticles. In this approach, 5-nm-diameter lanthanum phosphate nanoparticles doped with 225Ac and La(225Ac)PO4 successfully sequestered radionuclides and daughter products due to the radiation-tolerant crystal structure of monazite. In addition to the high radiolabeling efficiency of La(225Ac)PO4 nanoparticles with 225Ac (66 ± 4%), both radioactive daughters, 221Fr and 213Bi, exhibited >50% retention even after a week. A subsequent study (101) reported multishell nanoparticles comprising the lanthanide phosphate core that contained 225Ac and its radioactive daughters as well as several layers of gadolinium phosphate, conferring magnetic properties on the nanoparticle for easy separation, and an outer gold shell to utilize the nanoparticle’s established chemistry for nanoparticle functionalization. The multilayered nanoparticles—with four gadolinium shells—exhibited 99.99% 225Ac retention over 3 weeks. Daughter retention (up to 88%) increased with additional gadolinium phosphate shells. Interestingly, Piotrowska et al. (102) found that the first daughter of 225Ac, 221Fr, was well retained by biocompatible crystalline aluminosilicate nanozeolites (40 to 120 nm in diameter) when radiolabeled with 225Ra. These constructs also stably retained 225Ac in the presence of ethylene-diaminetetraacetic acid (≤5.5 ± 2.5% release) and in human blood serum (≤2.3 ± 1.9%).

4.4. Targeted α-Particle Delivery by Nanocarriers

Approaches utilizing nanometer-scale carriers to specifically deliver α-particle emitters have been designed to target the vascular endothelium (CNTs and liposomes), early-stage micrometastases (liposomes), and cancer cells in larger tumors (CNTs, liposomes, nanozeolites), as well as to increase permeability of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) (polymerized liposomes). In particular, Ruggiero et al. (103) covalently derived CNTs with cadherin targeting the E4G10 antibody with the goal of specifically targeting the tumor vascular endothelium. In a murine xenograft model of human colon adenocarcinoma (LS174T), CNTs that were also functionalized with 225Ac-DOTA exhibited reduced tumor volume and improved median survival relative to controls while sparing normal vascular endothelium (103).

In a proof-of-concept study targeting vasculature, lanthanum phosphate nanoparticles doped with 225Ac and La(225Ac)PO4, which retain both the parent and the radioactive daughters to a great extent, were functionalized with the mAb 201B targeting the mouse lung endothelium. They exhibited fast (within 1 h) and high specific uptake (~30% of the total injected dose) by the lungs in mice upon intravenous administration (100), demonstrating the potential of this approach. Similarly, larger (~382-nm-diameter) PEGylated multilayered nanoparticles functionalized with the same antibody—targeting the thrombomodulin receptors in the lung endothelium—demonstrated fast and high uptake by the lungs in mice upon intravenous administration (101).

In another study for antivascular α-particle therapy, PEGylated liposomes stably loaded with 225Ac-DOTA were functionalized with the mouse anti–human PSMA J591 antibody or with the A10 PSMA aptamer targeting PSMA. In cytotoxicity studies against human umbilical vein en-dothelial cells that were induced to express human PSMA, Bandekar et al. (104) demonstrated that targeted liposomes exhibited comparable median lethal dose values to the values measured for the radiolabeled J591 antibody.

For the treatment of early-stage micrometastases, Lingappa et al. (105) used a rat neu tumor on a transgenic model of mammary carcinoma with multiple metastatic organs to evaluate the efficacy of 213Bi-DTPA-labeled 100-nm-diameter liposomes functionalized with the 7.16.4 rat HER2/neu antibody attached to the free-chain ends of surface-grafted PEG. The median survival times demonstrated that antibody-targeted 213Bi-radiolabeled liposomes were as effective as the corresponding radiolabeled antibody in treating early-stage micrometastases.

To treat a lymphoma xenograft in a mouse model, Mulvey et al. (106) developed a two-step pretargeting approach that utilized 225Ac-DOTA-functionalized CNTs radiolabeled with high specific activities. In particular, an anti-CD20-MORF component was used for pretargeting, followed by the fast-clearing therapeutic [225Ac]DOTA-labeled CNTs modified with a morpholino (cMORF) oligonucleotide sequence that was complementary to the pretargeted anti-CD20-MORF sequence. The improved efficacy that was observed with the two-step approach in vivo (106) was attributed to the internalization of the radiolabeled constructs. The rapid elimination in the urine of the untargeted radiolabeled construct alleviated radioisotope toxicity.

Selective targeting of glioma cells in vitro was studied by Piotrowska et al. (107) by synthesizing NaA nanozeolites conjugated to the NK1-targeting substance P(5–11) peptide fragment. The NaA–silane–PEG–SP(5–11) conjugates were stably labeled with 223Ra and exhibited specific affinity toward the NK1 receptor accompanied by a high cytotoxic effect in vitro, demonstrating the potential of this approach for targeting glioma cells.

In a recent study (108), α-particle irradiation causing increased double-strand DNA breaks was correlated to increased permeation of the BBB and of the highly torturous, newly formed tumor vasculature [blood–tumor barrier (BTB)] in a glioblastoma animal model. 225Ac-labeled αvβ3-specific liposomes were intratumorally administered in nude mice bearing orthotopically implanted human glioblastoma tumors. The well-characterized integrin αvβ3 was chosen because of its high expression by the tumor endothelium and by glioblastoma cells. In particular, systemic delivery of Evans Blue dye (used as surrogate of small-molecule chemotherapy) and of fluorescent poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles (300 nm) demonstrated increased permeability of the BBB and BTB, not because of surgical disruption but rather because of α-particle irradiation. In this study, the polymerized, radiolabeled liposomes containing DOTA-functionalized lipids had a high radiochemical purity of 99.6% and a diameter of ~100 nm.

4.5. Intracellular Localization of α-Particle Emitters

Although the significance of intracellular localization has been studied for shorter-range (e.g., Auger) emitters, two studies have evaluated the role of intracellular localization of α-particle emitters on affecting the probability of the cell nucleus being traversed by the emitted α-particles and/or of the α-particle recoil nuclei possibly controlling the efficacy of killing. Rosenkranz et al. (109) designed a modular recombinant transporter (MRT), a targeted 211At delivery carrier, that encompassed the following four modules: a targeted moiety to bind to and become internalized by overexpressed epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) on cancer cells, a nuclear localization sequence of simian vacuolating virus 40, a translocation domain of diphtheria toxin for endosomal escape, and the Escherichia coli hemoglobin-like protein as the carrier. The MRT exhibited 10–20-times-greater cytotoxicity of different EGFR-positive cell lines compared with [211At]astatide; this finding was attributed to a geometrically more favorable localization of the former relative to the cell nucleus.

The importance of intracellular localization of 225Ac was studied by Zhu et al. (110), who demonstrated that nanoconjugation of targeting ligands resulted in nanoparticles’ perinuclear localization, essentially placing the delivered α-particle emitters next to the nuclei of targeted cancer cells. This study demonstrated improvement in the killing efficacy of delivered α-particle emitters in comparison to the killing effects of the same radioactivity levels delivered by targeting antibodies; the latter were shown—upon targeting and internalization—to localize in intracellular compartments closer to the plasma membrane. These findings were supported by greater levels of double-strand DNA breaks within the nucleus when cells were exposed to nanoparticles, as demonstrated by increased densities of γH2AX foci.

4.6. α-Particle Therapy for Solid Tumors

Therapy directed toward solid tumors by α-particle emitters has traditionally not been explored because of the relatively short range of α-particles combined with the limited solid tumor penetration of radionuclide carriers (111). Recently, Zhu et al. (112) demonstrated the potential of α-particle emitters to control the growth of solid tumors by designing delivery nanocarriers (liposomes) that release highly diffusing molecular forms of 225Ac within the tumor interstitium. The liposomes were designed to be pH responsive and to release their contents in conditions with slightly acidic pH (~6.5), which is relevant to several types of aggressive solid tumors (113). In vitro, this approach resulted in almost-uniform radioactivity distributions within 400-μm-diameter cancer cell spheroids (used as surrogates of avascular tumor regions) in the absence of cell targeting. In vivo, in animals with orthotopic xenografts of human triple-negative breast cancer, this approach improved OS and median survival compared with animals treated with nanocarriers lacking the release property and with a radiolabeled antibody targeting low levels of receptors on tumor cells. This study demonstrated the therapeutic potential of a general strategy for α-particle emitters to bypass the diffusion-limited transport of radionuclide carriers in solid tumors, independently of cell targeting.

Along the same lines is a nonsystemically administered approach that involves brachytherapy implants of 224Ra-loaded wires that have demonstrated high potential. Their efficacy was attributed to the diffusion of the α-particle-emitting daughters of implanted 224Ra in the tumor region surrounding the wire (114). An interesting future direction in this particular type of brachytherapy would be stimulation of specific antitumor immunity by the tumor antigens originating from the destroyed tumor (115). Studies on the effects of α-particle radiation (via radioimmunotherapy, for example), when combined with adoptive T cell transfer to induce immune responses that better control tumor growth (116), may help determine the direction of the next type of immunotherapies.

5. SUMMARY

α-Particle radionuclides present unique radiopharmaceutical characteristics. A combination of the latter with improved radiochemistry of α-particle radionuclides has contributed to the recently increased interest in α-particle radiotherapy. In the clinic, targeted therapy strategies have already demonstrated the ability to safely and efficaciously use α-particle emitters. At the preclinical stage, investigations of new approaches may ultimately result in improved clinical tools to treat cancer.

Acknowledgments

S.S. was supported in part by an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant (RSG-12-044-01) and National Science Foundation grants (DMR1207022 and CBET1510015).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

M.R.M. is a consultant for Medactinium, Inc., and Pharmactinium, Inc. G.S. is an author of patents related to α-emitter dosimetry and is a founder of a start-up that provides imaging and dosimetry services to radiopharmaceutical companies. S.S. is not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Schales F. Brief history of Ra-224 usage in radiotherapy and radiobiology. Health Phys. 1978;35:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macklis RM. The great radium scandal. Sci Am. 1993;269:94–99. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0893-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martland HS. Occupational poisoning in manufacture of luminous watch dials—general review of hazard caused by ingestion of luminous paint, with especial reference to the New Jersey cases. J Am Med Assoc. 1929;92:466–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baserga R, Yokoo H, Henegar GC. Thorotrast-induced cancer in man. Cancer. 1960;13:1021–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196009/10)13:5<1021::aid-cncr2820130524>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O’Sullivan JM, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jurcic JG, Ravandi F, Pagel JM, Park JH, Smith BD, et al. Phase I trial of targeted alpha-particle therapy using actinium-225 (225Ac)–lintuzumab (anti-CD33) in combination with low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) for older patients with untreated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2014;124:5293. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kratochwil C, Bruchertseifer F, Giesel FL, Weis M, Verburg FA, et al. 225Ac-PSMA-617 for PSMA-targeted α-radiation therapy of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1941–44. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.178673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordier D, Forrer F, Bruchertseifer F, Morgenstern A, Apostolidis C, et al. Targeted alpha-radionuclide therapy of functionally critically located gliomas with 213Bi-DOTA-[Thi8,Met(O2)11]-substance P: a pilot trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1335–44. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sgouros G. Radiobiology and Dosimetry for Radiopharmaceutical Therapy with Alpha-Particle Emitters. Reston, VA: Soc. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barendsen GW, Koot CJ, van Kerson GR, Bewley DK, Field SB, Parnell CJ. The effect of oxygen on the impairment of the proliferative capacity of human cells in culture by ionizing radiations of different LET. Int J Radiat Biol. 1966;10:317–27. doi: 10.1080/09553006614550421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barendsen GW, Walter HMD. Effects of different ionizing radiations on human cells in tissue culture., 4 Modification of radiation damage. Radiat Res. 1964;21:314–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barendsen GW. Impairment of the proliferative capacity of human cells in culture by alpha-particles with differing linear-energy transfer. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1964;8:453–66. doi: 10.1080/09553006414550561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barendsen GW, Walter HMD, Bewley DK, Fowler JF. Effects of different ionizing radiations on human cells in tissue culture. 3 Experiments with cyclotron-accelerated alpha-particles and deuterons. Radiat Res. 1963;18:106–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barendsen GW. Dose-survival curves of human cells in tissue culture irradiated with alpha-, beta-, 20-KV. X- and 200-KV X-radiation. Nature. 1962;193:1153–55. doi: 10.1038/1931153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barendsen GW, Vergroesen AJ. Irradiation of human cells in tissue culture with alpha-rays, beta-rays and X-rays. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1960;2:441. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodhead DT, Munson RJ, Thacker J, Cox R. Mutation and inactivation of cultured mammalian cells exposed to beams of accelerated heavy ions. 4 Biophysical interpretation. Int J Radiat Biol. 1980;37:135–67. doi: 10.1080/09553008014550201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox R, Masson WK. Mutation and inactivation of cultured mammalian cells exposed to beams of accelerated heavy ions. 3 Human-diploid fibroblasts. Int J Radiat Biol. 1979;36:149–60. doi: 10.1080/09553007914550901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballangrud ÅM, Yang WH, Charlton DE, McDevitt MR, Hamacher KA, et al. Response of LNCaP spheroids after treatment with an alpha-particle emitter (213Bi)-labeled anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen antibody ( J591) Cancer Res. 2001;61:2008–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballangrud ÅM, Yang WH, Hamacher KA, McDevitt MR, Ma D, et al. Relative efficacy of the alpha-particle emitters Bi-213 and Ac-225 for radioimmunotherapy against micrometastases. Proceedings of the 41st Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; La Jolla: Univ. Calif; 2000. p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barendsen GW, Beusker TLJ, Vergroesen AJ, Budke L. Effect of different ionizing radiations on human cells in tissue culture. 2. Biol Exp Radiat Res. 1960;13:841–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bloomer WD, McLaughlin WH, Neirinckx RD, Adelstein SJ, Gordon PR, et al. Astatine-211–tellurium radiocolloid cures experimental malignant ascites. Science. 1981;212:340–41. doi: 10.1126/science.7209534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humm JL. A microdosimetric model of astatine-211 labeled antibodies for radioimmunotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13:1767–73. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humm JL, Chin LM. A model of cell inactivation by alpha-particle internal emitters. Radiat Res. 1993;134:143–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassis AI, Harris CR, Adelstein SJ, Ruth TJ, Lambrecht R, Wolf AP. The in vitro radiobiology of astatine-211 decay. Radiat Res. 1986;105:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozak RW, Atcher RW, Gansow OA, Friedman AM, Hines JJ, Waldmann TA. Bismuth-212-labeled anti-Tac monoclonal-antibody: alpha-particle-emitting radionuclides as modalities for radioimmunotherapy. PNAS. 1986;83:474–78. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtzman SH, Russo A, Mitchell JB, DeGraff W, Sindelar WF, et al. Bismuth-212 linked to an antipancreatic carcinoma antibody: model for alpha-particle-emitter radioimmunotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:449–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.6.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macklis RM, Kinsey BM, Kassis AI, Ferrara JLM, Atcher RW, et al. Radioimmunotherapy with alpha-particle-emitting immunoconjugates. Science. 1988;240:1024–26. doi: 10.1126/science.2897133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDevitt MR, Ma D, Lai LT, Simon J, Borchardt P, et al. Tumor therapy with targeted atomic nanogenerators. Science. 2001;294:1537–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1064126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raju MR, Eisen Y, Carpenter S, Inkret WC. Radiobiology of alpha-particles. 3 Cell inactivation by alpha-particle traversals of the cell nucleus. Radiat Res. 1991;128:204–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sgouros G, Ballangrud ÅM, Jurcic JG, McDevitt MR, Humm JL, et al. Pharmacokinetics and dosimetry of an alpha-particle emitter labeled antibody: 213Bi-HuM195 (anti-CD33) in patients with leukemia. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1935–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballangrud ÅM, Yang WH, Palm S, Enmon R, Borchardt PE, et al. Alpha-particle-emitting atomic generator (actinium-225)-labeled trastuzumab (Herceptin) targeting of breast cancer spheroids: efficacy versus HER2/neu expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4489–97. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song H, Hedayati M, Hobbs RF, Shao C, Bruchertseifer F, et al. Targeting aberrant DNA double strand break repair in triple negative breast cancer with alpha particle emitter radiolabeled anti-EGFR antibody. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2043–54. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolch WE, Eckerman KF, Sgouros G, Thomas SR. A generalized schema for radiopharmaceutical dosimetry—standardization of nomenclature. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:477–84. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hobbs RF, Song H, Huso DL, Sundel MH, Sgouros G. A nephron-based model of the kidneys for macro-to-micro alpha-particle dosimetry. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:4403–24. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/13/4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hobbs RF, Song H, Watchman CJ, Bolch WE, Aksnes AK, et al. A bone marrow toxicity model for 223Ra alpha-emitter radiopharmaceutical therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:3207–22. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/10/3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sgouros G, editor. MIRD Monograph: Radiobiology and Dosimetry for Radiopharmaceutical Therapy with Alpha-Particle Emitters. Reston, VA: Soc. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jurcic JG, McDevitt MR, Pandit-Taskar N, Divgi CR, Finn RD, et al. Alpha-particle immunotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with bismuth-213 and actinium-225. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2006;21:396. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kratochwil C, Bruchertseifer F, Rathke H, Bronzel M, Apostolidis C, et al. Targeted αtherapy of mCRPC with 225actinium-PSMA-617: dosimetry estimate and empirical dose finding. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1624–31. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.191395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corson DR, MacKenzie KR, Segr E. Artificially radioactive element 85. Phys Rev. 1940;58:672–78. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauck ML, Larsen RH, Welsh PC, Zalutsky MR. Cytotoxicity of alpha-particle-emitting astatine-211-labelled antibody in tumour spheroids: no effect of hyperthermia. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:753–59. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsen RH, Akabani G, Welsh P, Zalutsky MR. The cytotoxicity and microdosimetry of astatine-211-labeled chimeric monoclonal antibodies in human glioma and melanoma cells in vitro. Radiat Res. 1998;149:155–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akabani G, Carlin S, Welsh P, Zalutsky MR. In vitro cytotoxicity of 211At-labeled trastuzumab in human breast cancer cell lines: effect of specific activity and HER2 receptor heterogeneity on survival fraction. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:333–47. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrich T, Korkmaz Z, Krull D, Frömke C, Meyer GJ, Knapp WH. In vitro experimental 211At-anti-CD33 antibody therapy of leukaemia cells overcomes cellular resistance seen in vivo against gem-tuzumab ozogamicin. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:851–61. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1356-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elgqvist J, Andersson H, Back T, Hultborn R, Jensen H, et al. Therapeutic efficacy and tumor dose estimations in radioimmunotherapy of intraperitoneally growing OVCAR-3 cells in nude mice with At-211-labeled monoclonal antibody MX35. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1907–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green DJ, Shadman M, Jones JC, Frayo SL, Kenoyer AL, et al. Astatine-211 conjugated to an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody eradicates disseminated B-cell lymphoma in a mouse model. Blood. 2015;125:2111–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-612770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burtner CR, Chandrasekaran D, Santos EB, Beard BC, Adair JE, et al. 211Astatine-conjugated monoclonal CD45 antibody–based nonmyeloablative conditioning for stem cell gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2015;26:399–406. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiess AP, Minn I, Vaidyanathan G, Hobbs RF, Josefsson A, et al. (2S)-2-(3-(1-Carboxy-5-(4-211At-astatobenzamido)pentyl)ureido)-pentanedioic acid for PSMA-targeted alpha-particle radiopharmaceutical therapy. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1569–75. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.174300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyczko M, Pruszynski M, Majkowska-Pilip A, Lyczko K, Was B, et al. 211At labeled substance P(5–11) as potential radiopharmaceutical for glioma treatment. Nucl Med Biol. 2017;53:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zalutsky MR, Reardon DA, Akabani G, Coleman RE, Friedman AH, et al. Clinical experience with α-particle emitting 211At: treatment of recurrent brain tumor patients with 211At-labeled chimeric antitenascin monoclonal antibody 81C6. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:30–38. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andersson H, Cederkrantz E, Bäck T, Divgi C, Elgqvist J, et al. Intraperitoneal α-particle radioimmunotherapy of ovarian cancer patients: pharmacokinetics and dosimetry of 211At-MX35 F(ab′)2—a phase I study. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1153–60. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.062604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brechbiel MW, Pippin CG, McMury TJ, Milenic D, Roselli M, et al. An effective chelating agent for labeling of monoclonal antibody with 212Bi for alpha-particle-mediated radioimmunotherapy. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1991;17:1169–70. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Junghans RP, Dobbs D, Brechbiel MW, Mirzadeh S, Raubitschek AA, et al. Pharmacokinet-ics and bioactivity of 1,4,7,10-tetra-azacylododecane N,N′,N″,N‴-tetraacetic acid (DOTA)-bismuth-conjugated anti-Tac antibody for α-emitter (212Bi) therapy. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5683–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huneke RB, Pippin CG, Squire RA, Brechbiel MW, Gansow OA, Strand M. Effective alpha-particle-mediated radioimmunotherapy of murine leukemia. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5818–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartmann F, Horak EM, Garmestani K, Wu C, Brechbiel MW, et al. Radioimmunotherapy of nude mice bearing a human interleukin 2 receptor α–expressing lymphoma utilizing the α-emitting radionuclide–conjugated monoclonal antibody 212Bi-anti-Tac. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4362–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rotmensch J, Whitlock JL, Schwartz JL, Hines JJ, Reba RC, Harper PV. In vitro and in vivo studies on the development of the alpha-emitting radionuclide bismuth 212 for intraperitoneal use against microscopic ovarian carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:833–40. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hassfjell SP, Bruland OS, Hoff P. Bi-212-DOTMP: An alpha particle emitting bone-seeking agent for targeted radiotherapy. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:231–37. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jurcic JG, McDevitt MR, Sgouros G, Ballangrud ÅM, Finn RD, et al. Targeted alpha-particle therapy for myeloid leukemias: a phase I trial of bismuth-213-HuM195 (anti-CD33) Blood. 1997;90:2245. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kneifel S, Cordier D, Good S, Ionescu MCS, Ghaffari A, et al. Local targeting of malignant gliomas by the diffusible peptidic vector 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1-glutaric acid-4,7,10-triacetic acid–substance P. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3843–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heeger S, Moldenhauer G, Egerer G, Wesch H, Martin S, et al. Alpha-radioimmunotherapy of B-lineage non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma using 213Bi-labelled anti-CD19-and anti-CD20-CHX-A-DTPA conjugates. Abstr Pap Am Chem Soc. 2003;225:U261. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raja C, Graham P, Rizvi S, Song E, Goldsmith H, et al. Interim analysis of toxicity and response in phase 1 trial of systemic targeted alpha therapy for metastatic melanoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:846–52. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.6.4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chappell LL, Dadachova E, Milenic DE, Garmestani K, Wu C, Brechbiel MW. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a novel bifunctional chelating agent for the lead isotopes 203Pb and 212Pb. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meredith RF, Torgue J, Azure MT, Shen S, Saddekni S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and imaging of Pb-212-TCMC-trastuzumab after intraperitoneal administration in ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2014;29:12–17. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2013.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meredith R, Torgue J, Shen S, Fisher DR, Banaga E, et al. Dose escalation and dosimetry of first-in-human alpha radioimmunotherapy with Pb-212-TCMC-trastuzumab. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1636–42. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.143842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang T, Zhu J, George DJ, Armstrong AJ. Enzalutamide versus abiraterone acetate for the treatment of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:473–85. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.995090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lorente D, Mateo J, Perez-Lopez R, de Bono JS, Attard G. Sequencing of agents in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e279–92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramdahl T, Bonge-Hansen HT, Ryan OB, Larsen S, Herstad G, et al. An efficient chelator for complexation of thorium-227. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016;26:4318–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dahle J, Borrebæk J, Melhus KB, Bruland ØS, Salberg G, et al. Initial evaluation of 227Th-p-benzyl-DOTA-rituximab for low-dose rate α-particle radioimmunotherapy. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:271–79. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dahle J, Krogh C, Melhus KB, Borrebæk J, Larsen RH, Kvinnsland Y. In vitro cytotoxicity of low-dose-rate radioimmunotherapy by the alpha-emitting radioimmunoconjugate thorium-227–DOTA–rituximab. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:886–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abbas N, Heyerdahl H, Bruland ØS, Borrebæk J, Nesland J, Dahle J. Experimental α-particle radioimmunotherapy of breast cancer using 227Th-labeled p-benzyl–DOTA–trastuzumab. EJNMMI Res. 2011;1:1–12. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hagemann UB, Wickstroem K, Wang E, Shea AO, Sponheim K, et al. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of a novel CD33-targeted thorium-227 conjugate for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:2422–31. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaelin WG. The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:689–98. doi: 10.1038/nrc1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McDevitt MR, Sgouros G, Finn RD, Humm JL, Jurcic JG, et al. Radioimmunotherapy with alpha-emitting nuclides. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25:1341–51. doi: 10.1007/s002590050306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McDevitt MR, Finn RD, Sgouros G, Ma D, Scheinberg DA. An 225Ac/213Bi generator system for therapeutic clinical applications: construction and operation. Appl Radiat Isot. 1999;50:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(98)00151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McDevitt MR, Ma D, Simon J, Frank RK, Scheinberg DA. Design and synthesis of 225Ac radioimmunopharmaceuticals. Appl Radiat Isot. 2002;57:841–47. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(02)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abou DS, Pickett J, Mattson JE, Thorek DLJ. A radium-223 microgenerator from cyclotron-produced trace actinium-227. Appl Radiat Isot. 2017;119:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Florimonte L, Dellavedova L, Maffioli LS. Radium-223 dichloride in clinical practice: a review. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1896–909. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lassmann M, Nosske D, Reiners C. Therapy of ankylosing spondylitis with 224Ra-radium chloride: dosimetry and risk considerations. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2002;41:173–78. doi: 10.1007/s00411-002-0164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jurcic JG, Caron PC, Nikula TK, Papadopoulos EB, Finn RD, et al. Radiolabeled anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody M195 for myeloid leukemias. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5908–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jurcic JG, Larson SM, Sgouros G, McDevitt MR, Finn RD, et al. Targeted alpha particle immunotherapy for myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1233–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosenblat TL, McDevitt MR, Mulford DA, Pandit-Taskar N, Divgi CR, et al. Sequential cy-tarabine and alpha-particle immunotherapy with bismuth-213-lintuzumab (HuM195) for acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Can Res. 2010;16:5303–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jurcic J, Levy M, Park J, Ravandi F, Perl A, et al. Phase I trial of alpha-particle immunotherapy with 225Ac-lintuzumab and low-dose cytarabine in patients age 60 or older with untreated acute myeloid leukemia. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(Suppl 1):456. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jurcic JG, Ravandi F, Pagel JM, Park JH, Smith BD, et al. Phase I trial of alpha-particle therapy with actinium-225 (Ac-225)–lintuzumab (anti-CD33) and low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) in older patients with untreated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(Suppl):7050. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jurcic JG, Ravandi F, Pagel JM, Park JH, Smith BD, et al. Phase I trial of targeted alpha-particle immunotherapy with 225Ac–lintuzumab (anti-CD33) and low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) in older patients with untreated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2015;126:3794. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mauk MR, Gamble RC. Preparation of lipid vesicles containing high levels of entrapped radioactive cations. Anal Biochem. 1979;94:302–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Henriksen G, Schoultz BW, Michaelsen TE, Bruland ØS, Larsen RH. Sterically stabilized liposomes as a carrier for α-emitting radium and actinium radionuclides. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:441–49. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sofou S, Thomas JL, Lin H-Y, McDevitt MR, Scheinberg DA, Sgouros G. Engineered liposomes for potential α-particle therapy of metastatic cancer. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:253–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chang M-Y, Seideman J, Sofou S. Enhanced loading efficiency and retention of 225Ac in rigid liposomes for potential targeted therapy of micrometastases. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1274–82. doi: 10.1021/bc700440a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jurcic JG, Levy MY, Park JH, Ravandi F, Perl AE, et al. Phase I trial of targeted alpha-particle therapy with actinium-225 (225Ac)–lintuzumab and low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) in patients age 60 or older with untreated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2016;128:4050. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sofou S, Kappel BJ, Jaggi JS, McDevitt MR, Scheinberg DA, Sgouros G. Enhanced retention of the α-particle-emitting daughters of actinium-225 by liposome carriers. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:2061–67. doi: 10.1021/bc070075t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang G, de Kruijff RM, Rol A, Thijssen L, Mendes E, et al. Retention studies of recoiling daughter nuclides of 225Ac in polymer vesicles. Appl Radiat Isot. 2014;85:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sofou S, Enmon R, Palm S, Kappel B, Zanzonico P, et al. Large anti-HER2/neu liposomes for potential targeted intraperitoneal therapy of micrometastatic cancer. J Liposome Res. 2010;20:330–40. doi: 10.3109/08982100903544185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sofou S. Radionuclide carriers for targeting of cancer. Int J Nanomed. 2008;3:181–99. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gabizon AA. PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin: metamorphosis of an old drug into a new form of chemotherapy. Cancer Investig. 2001;19:424–36. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100103136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Keizer RJ, Huitema ADR, Schellens JHM, Beijnen JH. Clinical pharmacokinetics of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:493–507. doi: 10.2165/11531280-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Harrington KJ, Rowlinson-Busza G, Syrigos KN, Abra RM, Uster PS, et al. Influence of tumour size on uptake of 111In-DTPA-labelled PEGylated liposomes in a human tumour xenograft model. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:684–88. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gabizon A, Papahadjopoulos D. Liposome formulations with prolonged circulation time in blood and enhanced uptake by tumors. PNAS. 1988;85:6949–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]