The ends of metal stents can induce a hypertrophic response.1, 2 We describe 3 cases of lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) used for various indications that resulted in complete burial of the LAMSs in the gastric antral wall. We propose a possible mechanism and solution to avoid this pitfall. Two prior cases of buried LAMSs have been described in the gastric body, but this is the first series of buried stents in the gastric antrum.3, 4

Case and endoscopic methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board. Three patients, who were not surgical candidates, underwent placement of an LAMS for the following indications: (1) a 58-year-old man with biliary cirrhosis (Childs B) and large periductal varices with acute cholecystitis (Fig. 1); (2) a 65-year-old woman with a 5.5-cm recurrent (4 prior surgical procedures) painful hepatic cyst (Fig. 2); and (3) an 82-year-old man with a pseudocyst that developed intraprocedural bleeding. The LAMS used was the Axios stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass), 10 mm × 15 mm in all cases. The wall distance (cyst to gastric lumen) measured 4 to 5 mm in all cases. The stents were deployed uneventfully. In 2 cases, an additional pigtail stent was placed through the LAMS after our first experience with a completely buried LAMS. After 25 weeks, 6 weeks, and 11 weeks, respectively, at repeated endoscopy, all 3 stents were found to be completely buried in the gastric wall, and in 1 case, at 48 weeks, the stent had migrated completely into the gallbladder. In the latter case, there was complete inward migration of the stent into the gallbladder, whereas in the other 2 cases, it could be seen as the start of inward migration at least into the tract to the hepatic cyst and pseudocyst. All stents were successfully removed after balloon dilation of the tract and, in 2 cases, by advancing the endoscope into the gallbladder and the liver cyst/abscess to remove the LAMS. All 3 cases were subsequently successfully treated with pigtail stents alone (Video 1).

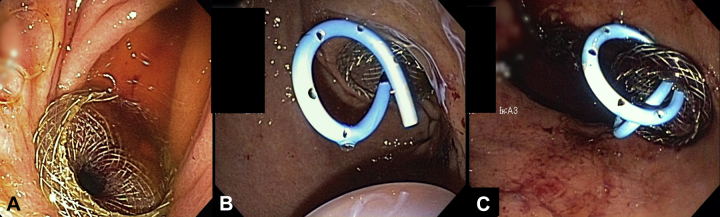

Figure 1.

Buried lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) in the prepyloric antrum in patients in whom stents were placed to drain (A) the gallbladder, (B) a hepatic cyst, and (C) a pseudocyst.

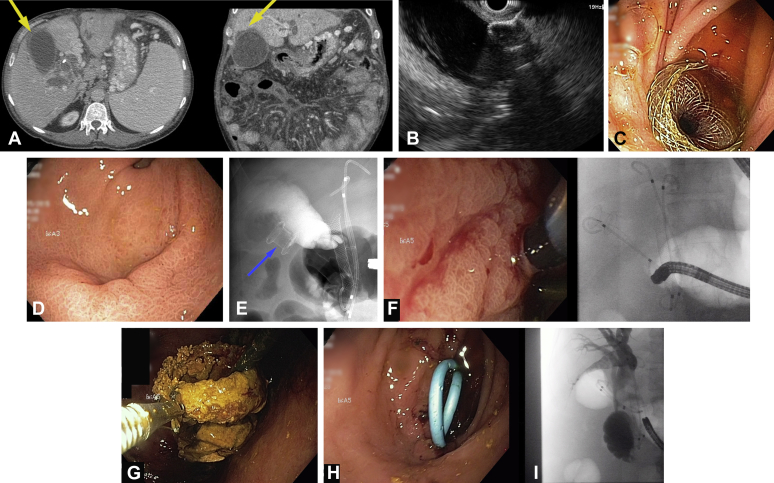

Figure 2.

A, CT scan demonstrating cholecystitis in a nonsurgical patient with large periductal varices and cirrhosis. B, Gallbladder flange of 15-mm lumen apposing metal stent (LAMS) deployed under EUS guidance. Note wall thickness was <10 mm. C, Endoscopic view of proximal flange of LAMS opened nicely. 6 months later, recurrent cholecystitis due to buried/internally migrating LAMS (within gastric wall); D, Endoscopic view and E, fluoroscopic view. F, 6 months later, recurrent cholecystitis. Endoscopic and fluoroscopic view of complete internal migration of LAMS into gallbladder. G, Endoscopic view of LAMS lined by stone cast in the gallbladder, eventually removed. H, I, Endoscopic and fluoroscopic view of 2 pigtail stents replacing the internally migrated LAMS.

Clinical implications

An important point to note in all 3 cases was that prior cross-sectional CT imaging did not demonstrate this inward migration/buried stent phenomenon, which was apparent only at endoscopy. Furthermore, the timing of this occurrence ranged from 6 weeks to 6 months; however, that may not be a reason to justify routine endoscopy to evaluate for this possible but rare adverse event.

The only common factor in these 3 cases was the location of stent placement (ie, the prepyloric gastric antrum). The majority of the stents placed at our institution are in the duodenal bulb for gallbladder drainage (n = 25) and in the gastric body for pancreatic necrosis (n = 40), where we had not previously encountered this adverse event. We suspect that motility in the gastric antrum results in more vigorous traction on the stent, producing a hypertrophic response on the gastric side. As a solution, we propose avoiding the gastric antrum if possible for placing LAMSs or using pigtail stents instead if possible. If a LAMS is used, place 1 or more pigtail stents through it to maintain stent patency. Finally, consider whether a longer flange on the LAMS would be less likely to result in this adverse event.

Disclosure

Dr Kozarek was on the advisory board for Axios during its development stage and did not receive financial or in-kind reimbursement in this role. All other authors disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this publication.

Footnotes

Written transcript of the video audio is available online at www.VideoGIE.org.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Irani S., Kozarek R.A. Gastrointestinal dilation and stent placement. In: Podolsky D.K., Camillera M., Fitz J.G., editors. Yamada's textbook of gastroenterology. 6th ed. Wiley & Sons Ltd; West Sussex, UK: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irani S., Baron T.H., Gluck M. Preventing migration of fully covered esophageal stents with an over-the-scope clip device (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabbri C., Luigiano C., Marsico M. A rare adverse event resulting from the use of a lumen-apposing metal stent for drainage of a pancreatic fluid collection: “the buried stent.”. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:585–587. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuklinski LF, Ferreira JD, Gordon SR, et al. Unintentional gastroduodenostomy complicating successful pancreatic necrosectomy with use of a double lumen-apposing stent. Gastrointest Endosc. Epub 2016 March 14. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.