Abstract

Restoration of tissue homeostasis by controlling stem cell aging is a promising therapeutic approach for geriatric disorders. The molecular mechanisms underlying age-related dysfunctions of specific types of adult tissue stem cells (TSCs) have been studied, and various microRNAs were recently reported to be involved. However, the central roles of microRNAs in stem cell aging remain unclear. Interest in this area was sparked by murine heterochronic parabiosis experiments, which demonstrated that systemic factors can restore the functions of TSCs. Age-related changes in secretion profiles, termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype, have attracted attention, and several pro- and anti-aging factors have been identified. On the other hand, many microRNAs are linked with the age-dependent dysregulations of various physiological processes, including “stem cell aging.” This review summarizes microRNAs that appear to play common roles in stem cell aging.

Keywords: Stem cell aging, microRNA, miR-17, miR-125b, miR-181a, SASP

Background

Overcoming age-related diseases and elongating the healthy lifespan are emerging issues for aging societies. Dysfunctions of aged tissue stem cells (TSCs) contribute to loss of tissue homeostasis, including reductions in lymphopoiesis and the long-term repopulating abilities of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSCs) [1, 2], the muscle repair capacity of skeletal muscle satellite cells [3], and the multipotency of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) [4]. The restoration of TSC functions in murine heterochronic parabiosis experiments triggered interest in the rejuvenation of aged TSCs [5]. Thereafter, several pro-aging [6–12] and anti-aging [13–16] systemic factors were identified, although some of the findings are conflicting [17]. Senescent cells secrete a myriad of inflammatory factors, referred to as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [18]. Clearance of senescent cells delays the induction of various geriatric pathologies, supporting the concept that the SASP promotes aging in a non-cell-autonomous fashion [19, 20]. Several lines of evidence indicated that age-related TSC dysfunctions and tissue-level pathologies can be improved by manipulating (reversing) cell-extrinsic/systemic conditions, at least in part.

We previously identified growth differentiation factor 6 (Gdf6; also known as Bmp13 and CDMP-2) as a regenerative factor secreted by young MSCs [21, 22]. Upregulation of human GDF6 restores the differentiation potential of old MSCs in vitro and reverses multiple age-related pathologies in vivo. miR-17 and its paralogues miR-106a and 106b (miR-17/106) regulate not only differentiation potential but also expression of some secretory factors, including Gdf6, and are implicated in the decline of these functions with age. Many microRNAs are associated with age-related dysfunctions of several types of TSCs. Here, we review microRNAs, which are commonly downregulated with age and induced dysregulation of cytogenesis, proliferation, and inflammation in multiple TSCs, and discuss functional similarities of microRNAs across different types of TSCs in aging.

miR-17 family (miR-17-92a, 106b-25, and 106a-363 clusters)

miR-17 family members play essential and pleiotropic roles in development, metabolism, diseases, tumorigenesis, and aging [23, 24]. We first identified miR-17/106 family members as key regulators of the neurogenic-to-gliogenic switch in developing neural stem/progenitor cells (NSCs) by controlling the “competence” necessary for NSCs to respond to gliogenic cell-extrinsic signals [25, 26]. Next, we found that downregulation of miR-17/106 induces a decline in differentiation potential and dysregulated expression of secretory factors in old MSCs [22]. Another group also reported a relationship between miR-17/106 and an age-dependent decrease in the osteogenic potential of MSCs [27]. miR-17/106 also regulate the proliferation and development of HSCs [28–30]. Other reports studied the impact of miR-17 overexpression in vivo. Transgenic mice expressing miR-17 exhibit delayed tissue growth and have an elongated lifespan [31, 32]. Epidemiologic studies reported that miR-17 family members are upregulated in centenarians, which supports the hypothesis that these microRNAs are important for the young healthy conditions and involved in human aging [33, 34].

miR-125b

A myeloid skewing phenotype and a decline in engraftment capability have long been recognized as age-related dysfunctions of old HSCs [1]. miR-125b is expressed in HSCs, and overexpression of miR-125b predominantly expands lymphoid-biased HSCs [35]. In addition, miR-125b can increase the level of myeloid progenitors [36]. Both reports showed that miR-125b overexpression increases the engraftment capabilities of HSCs and progenitors in transplantation assays into irradiated mice. Moreover, reduction of miR-125b increases expression levels of the chemokine CCL4 with age [37]. miR-125b activates and is activated by the NF-κB pathway [38, 39] is sometimes regarded as an “inflamma-miR,” which is implicated in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses [40]. miR-125b directly suppresses p53 expression in developing NSCs. miR-125b is expressed throughout zebrafish embryos and is enriched in the brain, while loss of miR-125b elevates p53 expression and triggers p53-dependent apoptosis in these embryos [41]. miR-125b is also expressed in MSCs [42], epidermal stem cells [43], and some types of tumor cells [44–48]. Interestingly, lin-4, a Caenorhabditis elegans homolog of miR-125b, is a heterochronic gene and generates the temporal pattern of many cell lineages during development [49], and is related to lifespan and tissue aging via its control of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor–1 pathway [50]. Overexpression of lin-4 elongates lifespan, whereas loss-of mutation accelerates tissue aging and shortens it.

miR-181 family (miR-181a/b/c/d)

Chronic inflammation accelerates systemic aging [10]. miR-181 family members have anti-inflammatory functions and are categorized as inflamma-miRs, together with miR-125b [40]. miR-181 regulates the differentiation of multiple types of TSCs, such as HSCs [51], myoblasts (activated progenitor cells) [52], MSCs [53], and some types of cancer stem cells [54–56]. We confirmed that miR-181 family members are downregulated with age in multiple TSCs (HSCs, MSCs, and intestinal stem cells). However, they continue to be expressed in differentiated cells and function pleiotropically. The age-dependent decline in miR-181a expression induces functional defects in CD4+ T cells [57]. miR-181a is downregulated in old pancreatic beta cells and necessary for their proliferation [58]. Extracellular vesicles derived from brain metastatic cancer cells contain miR-181c and can destroy and pass through the blood-brain barrier [59]. The critical roles of miR-181 in age-related cell-intrinsic dysfunctions of TSCs are unclear. The old TSCs with downregulated miR-181 family members would generate abnormal somatic cells, which have something dysfunctions, and these cells may contribute to the disturbance of tissue homeostasis.

Commonality of microRNA functions among various types of TSCs

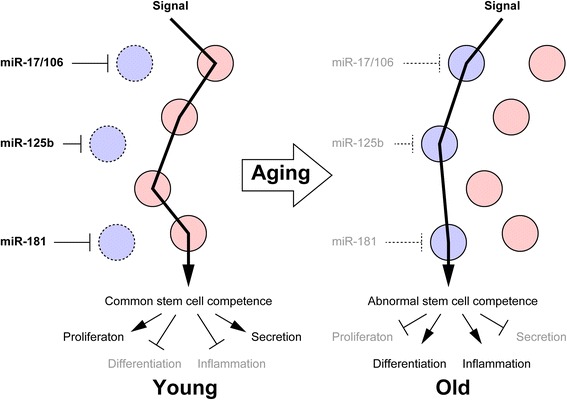

Recent studies have revealed that a part of microRNAs appear to play common roles in stem cell aging (Table 1). In fact, many microRNAs, including miR-17 family, miR-125b, and miR-181 family members, show similar expression pattern, namely they are expressed at higher levels during proliferating phase and downregulated with age. This is supported by a report concerning the classification of tumor cells derived from various tissues based on their microRNA, not their mRNA, expression profiles, suggesting that the existence of functionally common microRNAs, at least, for proliferation and undifferentiated states [60]. We have focused on microRNA-mediated “competence regulation,” which is responsible for the responsiveness to the various cell-extrinsic signals, as the fundamental machinery controlling the properties of TSCs, and miR-17 family members are key regulators in this context [22, 25, 61]. In our previous study, we revealed that miR-17/106 switches the usages of JAK-STAT and BMP pathways from neurogenic to gliogenic signals [25]. In young states, microRNAs regulate signal transduction correctly. Downregulation of microRNAs with age should induce deregulation of signal transduction and reflect abnormal phenotypes to signals (Fig. 1). All miR-17, miR-125b, miR-181 family members are downregulated various old TSCs and downregulation of them suppresses cytogenesis, proliferation, and secretion of homeostatic factors and promotes inflammation and tumorigenesis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Functional similarities of microRNAs in different types of TSCs

| microRNA family | Differentiation (specification) | Proliferation, survival, and apoptosis | Secretion and inflammation | Tumorigenesis | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-17/106 | MSCs (↑Ad, ↑Os) [22, 27] NSCs (↑N, ↓G) [25] HSCs (↑B, ↑Ly, ↑My) [28–30] |

↑HSCs [28–30] | MSCs (↑Gdf6 and etc.) [22] | Lymphoma [28–30] | |

| miR-125b | HSCs (↑Ly, ↑My) [35, 36]MSCs (↑Ad, ↑Os) [42] Skin stem cells (↓Epi, ↓Oil, ↓HF) [43] |

↑HSCs [35, 36]↑NSCs [41] ↑Skin stem cells [43] |

HSCs (↓CCL4, ↑NF-κB, ↓TNFAIP3) [37, 39, 40] | Breast cancer [44] Hepatocellular carcinoma [45] Leukemia [46] Skin tumor [47] Stomach adenocarcinoma [48] |

↑HSC engraftment [35, 36] |

| miR-181 | HSCs (↑Ly) [51] Myoblasts (↑Muscle) [52] |

↑Beta cells [58] | HSCs (↓IL-1α, ↓c-fos, ↓NF-κB) [40] MSCs (↑IL-6) [53] |

Hepatic cancer stem cells [54] Breast cancer [55] Leukemia [56] |

↑T cell receptor sensitivity [57] ↑Blood-brain barrier destruction [59] |

↑: promotion/positive regulation, ↓: inhibition/negative regulation, Ad: adipocytes, Os: Osteoblasts, N: neurons, G: glial cells, B: B cells, Ly: lymphocytes, My: myeloid cells, Epi: epidermal cells, Oil: oil-gland cells, HF: hair follicle cells

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the disruption of microRNA-mediated stem cell competence. Decline in microRNAs for regulation of stem cell functions induces disruption of proper stem cell competence and dysfunctions

Conclusions

Some microRNAs have similar functions in different types of TSCs. Downregulation of these specific-microRNAs induces similar age-related dysfunctions of TSCs. These microRNAs may define the “young competence” by specifying the signal pathways with suppression of their regulon, including signal mediators and transcription factors. Further investigation of the roles of the other microRNAs in stem cell aging will help to elucidate the central molecular machinery of the aging and develop the next-generation therapeutic methods for geriatric diseases.

Funding

This work was supported by the Uehara Memorial Foundation and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP16K08602.

Abbreviations

- Gdf6

Growth differentiation factor 6

- HSCs

Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells

- miR-17/106

miR-17, miR-106a, and 106b

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells

- NSCs

Neural stem/progenitor cells

- SASP

Senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- TSCs

Tissue stem cells

Authors’ contributions

HNK drafted and completed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sudo K, Ema H, Morita Y, Nakauchi H. Age-associated characteristics of murine hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192(9):1273–1280. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi DJ, Bryder D, Zahn JM, Ahlenius H, Sonu R, Wagers AJ, Weissman IL. Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(26):9194–9199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503280102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renault V, Thornell LE, Eriksson PO, Butler-Browne G, Mouly V. Regenerative potential of human skeletal muscle during aging. Aging Cell. 2002;1(2):132–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2002.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou S, Greenberger JS, Epperly MW, Goff JP, Adler C, Leboff MS, Glowacki J. Age-related intrinsic changes in human bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation to osteoblasts. Aging Cell. 2008;7(3):335–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Wagers AJ, Girma ER, Weissman IL, Rando TA. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature. 2005;433(7027):760–764. doi: 10.1038/nature03260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acosta JC, O'Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, Fumagalli M, Da Costa M, Brown C, Popov N, et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133(6):1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salminen A, Ojala J, Kaarniranta K, Haapasalo A, Hiltunen M, Soininen H. Astrocytes in the aging brain express characteristics of senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34(1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villeda SA, Luo J, Mosher KI, Zou B, Britschgi M, Bieri G, Stan TM, Fainberg N, Ding Z, Eggel A, et al. The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature. 2011;477(7362):90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naito AT, Sumida T, Nomura S, Liu ML, Higo T, Nakagawa A, Okada K, Sakai T, Hashimoto A, Hara Y, et al. Complement C1q activates canonical Wnt signaling and promotes aging-related phenotypes. Cell. 2012;149(6):1298–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jurk D, Wilson C, Passos JF, Oakley F, Correia-Melo C, Greaves L, Saretzki G, Fox C, Lawless C, Anderson R, et al. Chronic inflammation induces telomere dysfunction and accelerates ageing in mice. Nat Commun. 2014;2:4172. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith LK, He Y, Park JS, Bieri G, Snethlage CE, Lin K, Gontier G, Wabl R, Plambeck KE. Udeochu J et al: beta2-microglobulin is a systemic pro-aging factor that impairs cognitive function and neurogenesis. Nat Med. 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Fry CS, Kirby TJ, Kosmac K, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA. Myogenic progenitor cells control extracellular matrix production by fibroblasts during skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20(1):56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loffredo FS, Steinhauser ML, Jay SM, Gannon J, Pancoast JR, Yalamanchi P, Sinha M, Dall'Osso C, Khong D, Shadrach JL, et al. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 2013;153(4):828–839. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elabd C, Cousin W, Upadhyayula P, Chen RY, Chooljian MS, Li J, Kung S, Jiang KP, Conboy IM. Oxytocin is an age-specific circulating hormone that is necessary for muscle maintenance and regeneration. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4082. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsimpardi L, Litterman NK, Schein PA, Miller CM, Loffredo FS, Wojtkiewicz GR, Chen JW, Lee RT, Wagers AJ, Rubin LL. Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science. 2014;344(6184):630–634. doi: 10.1126/science.1251141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinha M, Jang YC, Oh J, Khong D, Wu EY, Manohar R, Miller C, Regalado SG, Loffredo FS, Pancoast JR, et al. Restoring systemic GDF11 levels reverses age-related dysfunction in mouse skeletal muscle. Science. 2014;344(6184):649–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1251152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egerman MA, Cadena SM, Gilbert JA, Meyer A, Nelson HN, Swalley SE, Mallozzi C, Jacobi C, Jennings LL, Clay I, et al. GDF11 increases with age and inhibits skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Metab. 2015;22(1):164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coppe JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Munoz DP, Goldstein J, Nelson PS, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):2853–2868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL, van Deursen JM. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479(7372):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, Wijers ME, Sieben CJ, Zhong J, Saltness RA, Jeganathan KB, Verzosa GC, Pezeshki A, et al. Naturally occurring p16-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature. 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Hisamatsu D, Naka-Kaneda H. Reversing multiple age-related pathologies by controlling the senescence-associated secretory phenotype of stem cells. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11(11):1746–1747. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.194715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hisamatsu D, Ohno-Oishi M, Nakamura S, Mabuchi Y, Naka-Kaneda H. Growth differentiation factor 6 derived from mesenchymal stem/stromal cells reduces age-related functional deterioration in multiple tissues. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8(6):1259–1275. doi: 10.18632/aging.100982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mogilyansky E, Rigoutsos I. The miR-17/92 cluster: a comprehensive update on its genomics, genetics, functions and increasingly important and numerous roles in health and disease. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(12):1603–1614. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellago H, Bobbili MR, Grillari J. MicroRNA-17-5p: at the crossroads of Cancer and aging - a mini-review. Gerontology. 2017;63(1):20–28. doi: 10.1159/000447773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naka-Kaneda H, Nakamura S, Igarashi M, Aoi H, Kanki H, Tsuyama J, Tsutsumi S, Aburatani H, Shimazaki T, Okano H. The miR-17/106-p38 axis is a key regulator of the neurogenic-to-gliogenic transition in developing neural stem/progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(4):1604–1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315567111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimazaki T, Okano H. Heterochronic microRNAs in temporal specification of neural stem cells: application toward rejuvenation. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2016;2:15014. doi: 10.1038/npjamd.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W, Qi M, Konermann A, Zhang L, Jin F, Jin Y. The p53/miR-17/Smurf1 pathway mediates skeletal deformities in an age-related model via inhibiting the function of mesenchymal stem cells. Aging (Albany NY) 2015;7(3):205–218. doi: 10.18632/aging.100728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ventura A, Young AG, Winslow MM, Lintault L, Meissner A, Erkeland SJ, Newman J, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Stone JR, et al. Targeted deletion reveals essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17 through 92 family of miRNA clusters. Cell. 2008;132(5):875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meenhuis A, van Veelen PA, de Looper H, van Boxtel N, van den Berge IJ, Sun SM, Taskesen E, Stern P, de Ru AH, van Adrichem AJ, et al. MiR-17/20/93/106 promote hematopoietic cell expansion by targeting sequestosome 1-regulated pathways in mice. Blood. 2011;118(4):916–925. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-336487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Vecchiarelli-Federico LM, Li YJ, Egan SE, Spaner D, Hough MR, Ben-David Y. The miR-17-92 cluster expands multipotent hematopoietic progenitors whereas imbalanced expression of its individual oncogenic miRNAs promotes leukemia in mice. Blood. 2012;119(19):4486–4498. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-378687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shan SW, Lee DY, Deng Z, Shatseva T, Jeyapalan Z, Du WW, Zhang Y, Xuan JW, Yee SP, Siragam V, et al. MicroRNA MiR-17 retards tissue growth and represses fibronectin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(8):1031–1038. doi: 10.1038/ncb1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du WW, Yang W, Fang L, Xuan J, Li H, Khorshidi A, Gupta S, Li X, Yang BB. miR-17 extends mouse lifespan by inhibiting senescence signaling mediated by MKP7. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1355. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serna E, Gambini J, Borras C, Abdelaziz KM, Belenguer A, Sanchis P, Avellana JA, Rodriguez-Manas L, Vina J. Centenarians, but not octogenarians, up-regulate the expression of microRNAs. Sci Rep. 2012;2:961. doi: 10.1038/srep00961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gombar S, Jung HJ, Dong F, Calder B, Atzmon G, Barzilai N, Tian XL, Pothof J, Hoeijmakers JH, Campisi J, et al. Comprehensive microRNA profiling in B-cells of human centenarians by massively parallel sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ooi AG, Sahoo D, Adorno M, Wang Y, Weissman IL, Park CY. MicroRNA-125b expands hematopoietic stem cells and enriches for the lymphoid-balanced and lymphoid-biased subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(50):21505–21510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016218107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Gibson WS, Balazs AB, Baltimore D. MicroRNAs enriched in hematopoietic stem cells differentially regulate long-term hematopoietic output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(32):14235–14240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009798107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng NL, Chen X, Kim J, Shi AH, Nguyen C, Wersto R, Weng NP. MicroRNA-125b modulates inflammatory chemokine CCL4 expression in immune cells and its reduction causes CCL4 increase with age. Aging Cell. 2015;14(2):200–208. doi: 10.1111/acel.12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan G, Niu J, Shi Y, Ouyang H, Wu ZH. NF-kappaB-dependent microRNA-125b up-regulation promotes cell survival by targeting p38alpha upon ultraviolet radiation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(39):33036–33047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.383273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SW, Ramasamy K, Bouamar H, Lin AP, Jiang D, Aguiar RC. MicroRNAs miR-125a and miR-125b constitutively activate the NF-kappaB pathway by targeting the tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3, A20) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(20):7865–7870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rippo MR, Olivieri F, Monsurro V, Prattichizzo F, Albertini MC, Procopio AD. MitomiRs in human inflamm-aging: a hypothesis involving miR-181a, miR-34a and miR-146a. Exp Gerontol. 2014;56:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le MT, Teh C, Shyh-Chang N, Xie H, Zhou B, Korzh V, Lodish HF, Lim B. MicroRNA-125b is a novel negative regulator of p53. Genes Dev. 2009;23(7):862–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.1767609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu JM, Wu X, Gimble JM, Guan X, Freitas MA, Bunnell BA. Age-related changes in mesenchymal stem cells derived from rhesus macaque bone marrow. Aging Cell. 2011;10(1):66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Stokes N, Polak L, Fuchs E. Specific microRNAs are preferentially expressed by skin stem cells to balance self-renewal and early lineage commitment. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(3):294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saetrom P, Biesinger J, Li SM, Smith D, Thomas LF, Majzoub K, Rivas GE, Alluin J, Rossi JJ, Krontiris TG, et al. A risk variant in an miR-125b binding site in BMPR1B is associated with breast cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(18):7459–7465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JK, Noh JH, Jung KH, Eun JW, Bae HJ, Kim MG, Chang YG, Shen Q, Park WS, Lee JY, et al. Sirtuin7 oncogenic potential in human hepatocellular carcinoma and its regulation by the tumor suppressors MiR-125a-5p and MiR-125b. Hepatology. 2013;57(3):1055–1067. doi: 10.1002/hep.26101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.So AY, Sookram R, Chaudhuri AA, Minisandram A, Cheng D, Xie C, Lim EL, Flores YG, Jiang S, Kim JT, et al. Dual mechanisms by which miR-125b represses IRF4 to induce myeloid and B-cell leukemias. Blood. 2014;124(9):1502–1512. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-553842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Ge Y, Fuchs E. miR-125b can enhance skin tumor initiation and promote malignant progression by repressing differentiation and prolonging cell survival. Genes Dev. 2014;28(22):2532–2546. doi: 10.1101/gad.248377.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim BC, Jeong HO, Park D, Kim CH, Lee EK, Kim DH, Im E, Kim ND, Lee S, Yu BP, et al. Profiling age-related epigenetic markers of stomach adenocarcinoma in young and old subjects. Cancer Inform. 2015;14:47–54. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S16912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. Elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75(5):843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boehm M, Slack F. A developmental timing microRNA and its target regulate life span in C. Elegans. Science. 2005;310(5756):1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1115596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303(5654):83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naguibneva I, Ameyar-Zazoua M, Polesskaya A, Ait-Si-Ali S, Groisman R, Souidi M, Cuvellier S, Harel-Bellan A. The microRNA miR-181 targets the homeobox protein Hox-A11 during mammalian myoblast differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(3):278–284. doi: 10.1038/ncb1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu L, Wang Y, Fan H, Zhao X, Liu D, Hu Y, Kidd AR, 3rd, Bao J, Hou Y. MicroRNA-181a regulates local immune balance by inhibiting proliferation and immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30(8):1756–1770. doi: 10.1002/stem.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ji J, Yamashita T, Budhu A, Forgues M, Jia HL, Li C, Deng C, Wauthier E, Reid LM, Ye QH, et al. Identification of microRNA-181 by genome-wide screening as a critical player in EpCAM-positive hepatic cancer stem cells. Hepatology. 2009;50(2):472–480. doi: 10.1002/hep.22989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Yu Y, Tsuyada A, Ren X, Wu X, Stubblefield K, Rankin-Gee EK, Wang SE. Transforming growth factor-beta regulates the sphere-initiating stem cell-like feature in breast cancer through miRNA-181 and ATM. Oncogene. 2011;30(12):1470–1480. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Su R, Lin HS, Zhang XH, Yin XL, Ning HM, Liu B, Zhai PF, Gong JN, Shen C, Song L, et al. MiR-181 family: regulators of myeloid differentiation and acute myeloid leukemia as well as potential therapeutic targets. Oncogene. 2015;34(25):3226–3239. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li G, Yu M, Lee WW, Tsang M, Krishnan E, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Decline in miR-181a expression with age impairs T cell receptor sensitivity by increasing DUSP6 activity. Nat Med. 2012; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Tugay K, Guay C, Marques AC, Allagnat F, Locke JM, Harries LW, Rutter GA, Regazzi R. Role of microRNAs in the age-associated decline of pancreatic beta cell function in rat islets. Diabetologia. 2016;59(1):161–169. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3783-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tominaga N, Kosaka N, Ono M, Katsuda T, Yoshioka Y, Tamura K, Lotvall J, Nakagama H, Ochiya T. Brain metastatic cancer cells release microRNA-181c-containing extracellular vesicles capable of destructing blood-brain barrier. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6716. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435(7043):834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naka H, Nakamura S, Shimazaki T, Okano H. Requirement for COUP-TFI and II in the temporal specification of neural stem cells in CNS development. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(9):1014–1023. doi: 10.1038/nn.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]