Highlights

-

•

This is the first study which reports the ability of C. parapsilosis to produce biosurfactant. The organism was identified through morphology and sequencing studies. The biosurfactant was characterized and its potential antibacterial activity was explored.

Keywords: Candida, biosurfactant, characterization, docosenamide, antibacterial, broad spectrum

Abstract

In the present study, a biosurfactant producing Candida parapsilosis strain was isolated and identified by our laboratory. Different biosurfactant screening tests such as drop collapse, oil spreading, emulsification index and hemolytic activity confirmed the production of biosurfactant by the isolated Candida parapsilosis strain. The biosurfactant showed significant emulsifying index, drop collapse and oil-spread activity. The partially purified biosurfactant was characterized by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS). The FT-IR results indicated phenol (O—H), amide (N—H) and carbon functional group peaks like C O and C C at their identified places. GC-MS analysis revealed the presence of 13-docosenamide type of compound with a molecular weight of 337.5 g mol-1. The isolated biosurfactant showed significant antibacterial activity against pathogenic Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus strains at the concentrations of 10 and 5 mg ml-1 respectively. Growth inhibition of both Gram positive and Gram negative pathogenic strains designated the future prospect of exploring the isolated biosurfactant as broad spectrum antibacterial agent.

1. Introduction

Natural products are accomplished as important compounds which exhibit many applications in the fields of medicine, pharmacy and agriculture. Majority of antibiotics used for the treatment of various infectious diseases, are originated from microbial natural products. Starting from the discovery of penicillin in 1928, studies have shown that microorganisms are rich source of structurally unique bioactive substances [1]. In present scenario as Multi Drug Resistance is a major threat to society, search for new drugs is indispensable all over the world [2].

Biosurfactants are amphipathic molecules possessing immense structural diversity, biodegradability and less toxicity compared to synthetic ones [3]. Various microbes are known to produce different kinds of biosurfactants. Lipopeptide types are synthesized by Bacillus and other species, glycolipids types are synthesized by Pseudomonas and Candida species [4]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been known to produce rhamnolipid type of biosurfactant having different biological properties [5]. Surfactin, an important antimicrobial and antifungal agent is known to be produced from Bacillus subtilis [6]. Very recently Joanna et al., have reported a nonspecific synergistic antibacterial and anti-fungal effect of biogenic silver nanoparticles and biosurfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis towards environmental bacteria and fungi [7]. Lactobacillus species also produces biosurfactant that can contribute to the bacteria’s ability to prevent microbial infections associated with urogenital and gastrointestinal tracts and the skin [8]. Biosurfactants can replace synthetic surfactants and have potential biomedical, industrial and environmental applications and can be used as potential antibiotic agents as highlighted by Rodrigues et.al. [9]. Their potential application in products for human consumption such as biomedical, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals or as food additives requires an accurate characterization of possible toxic side effects [10].

The Candida parapsilosis family has emerged as a major opportunistic and nosocomial pathogen. It causes multifaceted pathology in immuno-compromised and normal hosts, notably low birth weight neonates. This fungus has emerged as major causes of human disease, particularly among immuno-compromised individuals and hospitalized patients with serious underlying conditions. Many microbes such as Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Azospirillum and Rhizobium were once considered to be toxic but over a period of time, many changes were made in the genes of these microbes and now they are exploited for commercial value products [11,12]. Different Candida sp. are already known to produce sophorolipids which are extracellular glycolipids [13]. Sophorolipids are the most common biosurfactants used in cosmetics and therapeutics [14]. Mannosyl erythritol lipid (MEL), a yeast glycolipid biosurfactant produced from vegetable oils by Candida strains has already been reported [15].

Present study describes the isolation of Candida parapsilosis from a contaminated dairy product. This is the first study which reports the ability of C. parapsilosis to produce biosurfactant. The organism was identified through morphology and sequencing studies. The biosurfactant was characterized and its potential antibacterial activity was explored.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

The potato dextrose broth (PDB), potato dextrose agar (PDA), nutrient agar media, glycerol and Phosphate Buffer Saline (pH 7) were purchased from HiMedia, Mumbai, India. All reagents used were of molecular biology grade unless mentioned and used as obtained. The bacterial cultures of Escherichia coli MTCC No. 1687 and Staphylococcus aureus MTCC No. 96 were procured from Microbial Type Culture Collection (MTCC, IMTECH, Chandigarh, India).

2.2. Microorganism and culture conditions

The microorganism was isolated from contaminated dairy products and grown in potato dextrose broth. The microbial culture was sub-cultured twice in PDB broth at 37 °C for 24 h. The strain was kept frozen at −80 °C in PDB broth containing 30% (v/v) glycerol solution until required. Both the test strains of E. coli and S. aureus were activated twice in nutrient broth at 37 °C for 24 h.

3. Molecular Characterization of the organism

3.1. MALDI Biotyper

The colony was analyzed by MALDI Biotyper (Bruker, Germany) [16]. The isolated single colony was transferred onto MALDI Biotyper Steel plate using a sterile loop and was analyzed.

3.2. Molecular Characterization

The molecular characterization report was provided by MTCC, Chandigarh, India. Based on the 26 S rRNA, 18 S rRNA, 28 S rRNA and ITS region sequence, the organism was identified.

3.3. Extraction of biosurfactant

The biosurfactant was extracted from cell-free broth of 72 hour grown cells. To extract the biosurfactant, cell-free supernatants were subjected to acid precipitation by subjecting supernatants to pH 2.0 with 6 N HCl. Afterwards, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation and pH was adjusted at 7.0. Finally, the biosurfactant solution was freeze-dried [17].

3.4. Screening of biosurfactant

Different biosurfactant screening methods were performed to check the presence of potential biosurfactant. The methods adopted were (a) drop-collapse test [18]; (b) Oil spreading technique [19]; (c) Emulsification activity [20] and (d) Hemolytic activity in 5% blood agar plate [19].

4. Characterization of biosurfactant

4.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer-Spectrum RX-IFTIR, U.S.A.) was carried out using crude biosurfactant extract obtained from the acid precipitation of the cell free culture supernatant. The FTIR spectrum, with a resolution of 4 cm-1, was collected from 400 to 4000 cm-1. The basic functional groups of the biosurfactant were analyzed [17].

4.2. Gas Chromatography- Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS)

GC-MS (Thermo Scientific TSQ 8000 Gas Chromatograph - Mass Spectrometer, U.S.A.) of partially purified biosurfactant was analyzed using gas chromatography. Helium was used as carrier gas with the flow rate of 1.0 ml min-1. The initial column temperature was 100 °C for 1 min, then ramped at 30 °C to 270 °C, and finally held at 270 °C for 10 min. The temperatures of the inlet temperature, transfer line, ion trap, and quadruple were 270, 280, 230, and 150 °C, respectively [21].

5. Antibacterial activity

5.1. Agar diffusion method

Nutrient Agar media was prepared. Plates were swabbed with E.coli and S. aureus cultures. Wells were made in the agar plates using a sterile well maker and then various concentrations of biosurfactant (0.3, 0.75, 1.50 mg ml-1) were added in separate well. The plates were kept in incubation at 37° C for 24 h. The clear zone diameter was noted [22].

5.2. Micro dilution method

The antibacterial activity of the biosurfactant was examined against the bacterial strains using micro dilution method [23]. Both the strains were cultured individually on nutrient broth at 37 °C overnight under aerobic conditions and the inoculums of each strain was adjusted to a concentration of 108 CFU ml-1 which corresponds to 0.50 McFarland Turbidity Standards [24]. The assay was carried out in a 96-well flat bottom polystyrene micro titer plates with lids. The first column of the well plate was filled with 125 μl of sterile double strength nutrient broth and the remaining columns were filled with single-strength nutrient broth. Subsequently, 125 μl of biosurfactant solution prepared using phosphate buffer saline (pH 7) at a concentration of 40 mg ml-1 was added to the first column and mixed with the medium, then serially diluted to the subsequent wells to attain a biosurfactant concentration ranging from 5 mg ml-1 to 20 mg ml-1. Growth controls were also there. The inoculated well plates were covered with lids and incubated at 37° C overnight. After incubation, the absorbance was recorded at 600 nm for each well using a microplate reader (iMARKTM Microplate Absorbance Reader, Bio-Rad, USA). The assays were performed in triplicate.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Characterization of organism

6.1.1. MALDI Biotyper

MALDI Biotyper is a rapid, inexpensive and at the same time very reliable tool for microbe identification [25]. The microbe was identified as Candida parapsilosis by MALDI Biotyper. However, the identification of isolate was further supported by 18 S rRNA gene sequencing.

6.1.2. Molecular characterization

As identified by the MALDI Biotyper, the isolate was an yeast and hence a 18 S rRNA gene sequencing was done [26]. Based on the 26 S rRNA, 18 S rRNA, 28 S rRNA and ITS region sequence, the organism was identified as C. parapsilosis. Comparative sequence analysis of the 18 S rRNA (690 bp) in the GenBank database was performed by a BLAST search and manually reading through the GenBank accession number as shown in Fig. 1. The gene sequence comparison demonstrated 100% similarities to Candida parapsilosis. Hence, MALDI Biotyper and molecular characterization data showed that the isolate was Candida parapsilosis.

Fig. 1.

Identification of Candida parapsilosis based on the 26 S rRNA, 18 S rRNA, 28 S rRNA and ITS region sequence through BLAST. Phylogenetic tree was generated using tools from NCBI.

6.1.3. Screening of biosurfactant

Different biosurfactant screening tests such as drop collapse test, oil spreading test, emulsification activity and hemolytic activity confirmed that C. parapsilosis was able to produce biosurfactant as shown in Table 1. The drop on the surface of oil coated wells collapsed which showed the presence of biosurfactant in the media. A clear zone was observed in the oil-water surface which confirmed presence of biosurfactant in oil spreading test. In emulsification index, the heights of each layer were taken and changes in the heights were noted after the settling periods. The methodology used and results obtained are well supported by the already available reports of biosurfactant screening [[27], [28], [29], [30]]. The current result of blood hemolysis was well corroborated with the report of Luo. et al. where tested isolates of C. parapsilosis neither showed α-hemolysis nor showed β-hemolysis even after 72 hours of incubation [31]. Screening methods such as drop collapse test, oil spreading test, emulsification activity and hemolytic activity are generally used as simple tools for the screening of the biosurfactant. The isolated biosurfactant showed gamma hemolysis but results are positive for drop collapse test, oil spreading test, emulsification activity. The absence of hemolytic activity (γ- hemolysis) could be due to diffusion restriction of the surfactant through the blood agar [32]. These assays are performed based on surface activity measurements and are well accepted as preliminary screening method of biosurfactants [19].

Table 1.

Table shows screening results for biosurfactant.

| Screening test | Result |

|---|---|

| Oil spreading assay | Positive |

| Drop collapse method | Positive |

| Emulsifying index | Positive |

| Hemolysis | Negative |

6.2. Characterization of biosurfactant

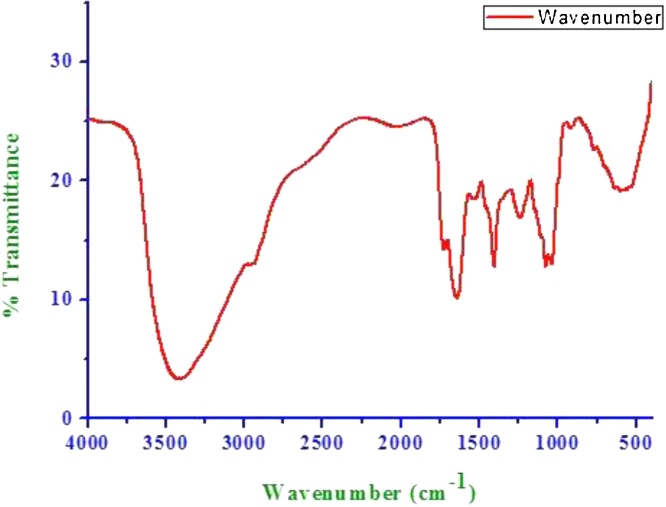

6.2.1. FTIR spectroscopy

The different peak of the IR spectral analysis shown in Fig. 2 revealed that, the stretch, 3409 cm-1 denoted as O-H group. The presence of this peak revealed the fact that the sample contains phenol or alcohol group. C = O bond stretching resulted peak at 1724 cm-1.The peak at 1638 cm-1 corresponded to N-H which could be due to an amide in the sample. The presence of the peak at 1403 cm-1 confirmed the presence of C = C. These functional groups were similar to previously reported biosurfactants produced by various other Candida sp [[33], [34], [35], [36]].

Fig. 2.

FTIR spectrum of the biosurfactant.

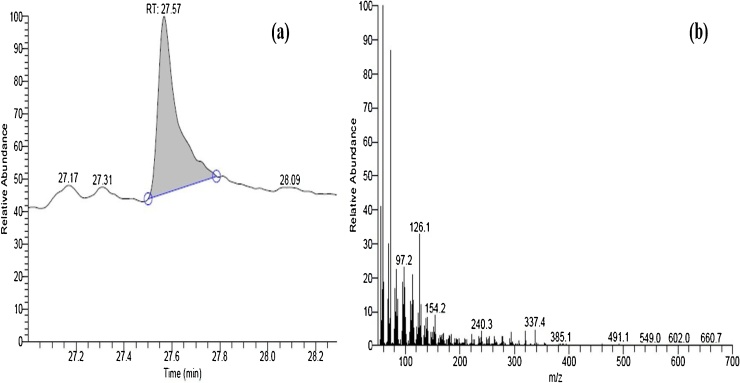

6.3. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

After performing the GC MS of the biosurfactant as shown in Fig. 3, major peaks were obtained at retention times of 4.27, 27.17, 27.57, 27.31 minute. The most dominant peak was that obtained at 27.57 min. The MS of this eluent was done by the system and the peaks obtained were matched with the system library. The molecule obtained at this retention time is 13-Docosenamide.The molecular weight of 13- Docosenamide is 337.5 g/mol and its characteristic MS spectra is shown in Fig. 3. GC-MS result shows the presence of 13-Docosenamide residues which correlates with other reports. This data corroborates with the FTIR of the biosurfactant produced in this study. The peaks corresponding to the functional groups obtained in the FTIR are present in docosenamide. This is the only third report after Donio et.al. and Conde-Martínez et.al. which showed docosenamide as a biosurfactant [17,37].

Fig. 3.

Graphs obtained from GC-MS, (a) shows GC whereas (b) shows MS at Retention time of 27.57 minutes. The molecule identified through library search was found to be 13-Docosenamide.

6.4. Antibacterial activity

6.4.1. Agar diffusion method

Partially purified biosurfactant from C. parapsilosis, showed antibacterial activity against bacterial pathogens, E. coli and S. aureus (From Table 2). In well diffusion assay, biosurfactant produced a zone of inhibition against S. aureus and E.coli. Higher concentrations of biosurfactant led to increase in the diameter of zone of inhibition. Higher concentrations of biosurfactant led to increase in the diameter of zone of inhibition. Maximum zone of inhibition was observed at biosurfactant concentration of 1.5 mg ml-1 wherein, it was approximately 2.87 cm for E. coli and 2.66 cm for S. aureus.

Table 2.

Effect of different concentrations of biosurfactant against E. coli and S. aureus measured by zone of inhibition diameter.

| Concentration of biosurfactant(mg ml-1) | Zone of inhibition diameter (in cm) mean (For E. coli) | Zone of inhibition diameter (in cm) mean (For S. aureus) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.30 | 2.19 ± 0.042 | 2.22 ± 0.009 |

| 0.75 | 2.45 ± 0.031 | 2.39 ± 0.004 |

| 1.50 | 2.87 ± 0.048 | 2.66 ± 0.012 |

Zone of inhibition diameters were found to be more for E. coli than S. aureus. The antibacterial results with current biosurfactant were comparable with those obtained from previous reports [[38], [39], [40]].

6.4.2. Microdilution method

The isolated biosurfactant was checked for antibacterial effects on E. coli and S. aureus by micro-dilution method also. The absorbance was recorded at 600 nm for each well using a microplate reader and is shown in Table 3.The crude biosurfactant isolated from Candida sphaerica showed the antimicrobial activity with concentrations between 5 and 10 mg ml-1 against C. albicans, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis [41]. A biosurfactant concentration between 25 and 50 mg ml−1 was required for antimicrobial activity against pathogenic Candida albicans, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Streptococcus agalactiae [42].These reports provided additional support to our current results which demonstrated that biosurfactant isolated from C. parapsilosis showed antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus at the concentrations of 10 and 5 mg ml-1 respectively.

Table 3.

Growth inhibition obtained with the crude at different concentrations (mg ml-1). Results are expressed as means ± standard deviations of values obtained from triplicate experiments.

| Organism | Biosurfactant concentration(mg ml-1) | O.D at 600 nm (mean) |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Control | 0.899 ± 0.0100 |

| 05 | 0.380 ± 0.0130 | |

| 10 | 0.180 ± 0.0040 | |

| 20 | 0.090 ± 0.0062 | |

| S. aureus | Control | 0.912 ± 0.0030 |

| 05 | 0.240 ± 0.0140 | |

| 10 | 0.085 ± 0.0157 | |

| 20 | 0.050 ± 0.0085 |

7. Conclusion

In the present study, biosurfactant was isolated from C. parapsilosis and partially characterized.The isolated biosurfactant showed the potential of an antibacterial agent. The experiments of this study suggested that C. parapsilosis can be explored for some beneficial uses in biopharmaceutics, therapeutics apart from their pathogenicity. Although the mode of action of biosurfactant is not clear now, but some reports have shown to disrupt plasma membrane of the cells and more studies need to be carried out to get a clear insight in this regard [43].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding publication of this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank UGC-BSR, Govt. of India for providing us the funds to carry out this research endeavor. Authors would like to thank Director, U.I.E.T., Panjab University, Chandigarh, India for allowing us to undertake this project. We also like to thank Director, C.I.L., Panjab University, Chandigarh, India for allowing us access to FTIR and GC-MS facility at their department. Suggestions from Dr. Rakesh Tuli, Research Advisor, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India are also acknowledged.

References

- 1.Nigam A., Gupta D., Sharma A. Treatment of infectious disease: Beyond antibiotics. Microbiological Research. 2014;169(9):643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack A., Relman D.A., Choffnes E.R. National Academies Press; 2011. Antibiotic resistance: implications for global health and novel intervention strategies: workshop summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards K.R., Lepo J.E., Lewis M.A. Toxicity comparison of biosurfactants and synthetic surfactants used in oil spill remediation to two estuarine species. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2003;46(10):1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(03)00238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maier R.M. Biosurfactants: Evolution and Diversity in Bacteria. Advances in Applied Microbiology. 2003;52:101–121. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(03)01004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang S., Wullbrandt D. Rhamnose lipids–biosynthesis, microbial production and application potential. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1999;51(1):22–32. doi: 10.1007/s002530051358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kameda Y., et al. Antitumor activity of Bacillus natto. V. Isolation and characterization of surfactin in the culture medium of Bacillus natto KMD 2311. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1974;22(4):938–944. doi: 10.1248/cpb.22.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joanna C., et al. A nonspecific synergistic effect of biogenic silver nanoparticles and biosurfactant towards environmental bacteria and fungi. Ecotoxicology. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10646-018-1899-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morais I.M.C., et al. Biological and physicochemical properties of biosurfactants produced by Lactobacillus jensenii P(6A) and Lactobacillus gasseri P(65) Microbial Cell Factories. 2017;16:155. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0769-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodrigues L., et al. Biosurfactants: potential applications in medicine. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2006;57(4):609–618. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vijayakumar S., Saravanan V. Biosurfactants-Types, Sources and Applications. Research Journal of Microbiology. 2015;10:181–192. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maejima K., Oshima K., Namba S. Exploring the phytoplasmas, plant pathogenic bacteria. Journal of General Plant Pathology. 2014;80(3):210–221. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allouche N., et al. Use of Whole Cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for Synthesis of the Antioxidant Hydroxytyrosol via Conversion of Tyrosol. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70(4) doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2105-2109.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elshafie A.E., et al. Sophorolipids Production by Candida bombicola ATCC 22214 and its Potential Application in Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;(6):1324. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morya V.K., et al. Medicinal and Cosmetic Potentials of Sophorolipids. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;13(12):1761–1768. doi: 10.2174/13895575113139990002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitamoto D., et al. Surface active properties and antimicrobial activities of mannosylerythritol lipids as biosurfactants produced by Candida antarctica. Journal of Biotechnology. 1993;29(1):91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starostin K.V., et al. Identification of Bacillus strains by MALDI TOF MS using geometric approach. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:16989. doi: 10.1038/srep16989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donio M.B.S., et al. Isolation and characterization of halophilic Bacillus sp. BS3 able to produce pharmacologically important biosurfactants. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2013;6(11):876–883. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60156-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morikawa M., et al. A new lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by Arthrobacter sp. strain MIS38. Journal of Bacteriology. 1993;175(20):6459–6466. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6459-6466.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulligan C.N., Cooper D.G., Neufeld R.J. Selection of Microbes Producing Biosurfactants in Media without Hydrocarbons. Journal of fermentation technology. 1984;62(4):311–314. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodour A.A., Maier R.M. Encyclopedia of Environmental Microbiology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2003. Biosurfactants: Types, Screening Methods, and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma D., et al. Production and Structural Characterization of Lactobacillus helveticus Derived Biosurfactant. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;(2014):9. doi: 10.1155/2014/493548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saravanakumari P., Mani K. Structural characterization of a novel xylolipid biosurfactant from Lactococcus lactis and analysis of antibacterial activity against multi-drug resistant pathogens. Bioresource Technology. 2010;101(22):8851–8854. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghribi D., et al. Investigation of Antimicrobial Activity and Statistical Optimization of Bacillus subtilis SPB1 Biosurfactant Production in Solid-State Fermentation. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2012;(2012):373682. doi: 10.1155/2012/373682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mcfarland J. The nephelometer: An instrument for estimating the number of bacteria in suspensions used for calculating the opsonic index and for vaccines. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1907;(14):1176–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singhal N., et al. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: an emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;(6):791. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanano A., Shaban M., Almousally I. Biochemical, Molecular, and Transcriptional Highlights of the Biosynthesis of an Effective Biosurfactant Produced by Bacillus safensis PHA3, a Petroleum-Dwelling Bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2017;8(77) doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi P.A., Shekhawat D.B. Screening and isolation of biosurfactant producing bacteria from petroleum contaminated soil. Euro J Exp Biol. 2014;4(4):164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nwaguma I.V., Chikere C.B., Okpokwasili G.C. Isolation, characterization, and application of biosurfactant by Klebsiella pneumoniae strain IVN51 isolated from hydrocarbon-polluted soil in Ogoniland, Nigeria. Bioresources and Bioprocessing. 2016;3(1):40. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma D., Saharan B.S. Functional characterization of biomedical potential of biosurfactant produced by Lactobacillus helveticus. Biotechnology Reports. 2016;11:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elazzazy A.M., Abdelmoneim T.S., Almaghrabi O.A. Isolation and characterization of biosurfactant production under extreme environmental conditions by alkali-halo-thermophilic bacteria from Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2015;22(4):466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo G., Samaranayake L.P., Yau J.Y.Y. Candida Species Exhibit Differential In Vitro Hemolytic Activities. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2001;39(8):2971–2974. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.8.2971-2974.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deepa R., Vidhya A., Arunadevi S. Screening of Bioemulsifier and Biosurfactant Producing Streptomyces from Different Soil Samples and Testing its Heavy metal Resistance Activity. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2015;4(5):687–694. [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Sheshtawy H.S., et al. Production of biosurfactants by Bacillus licheniformis and Candida albicans for application in microbial enhanced oil recovery. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum. 2016;25(3):293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta A.N., Debnath M. Proceedings of International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology (ICEST 2011) 2011. Characterization of Biosurfactant production by mutant strain of Candida tropicalis. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santos D.K.F., et al. Biosurfactant production from Candida lipolytica in bioreactor and evaluation of its toxicity for application as a bioremediation agent. Process Biochemistry. 2017;54:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verma A., et al. Multifactorial approach to biosurfactant production by adaptive strain Candida tropicalis MTCC 230 in the presence of hydrocarbons. Journal of Surfactants and Detergents. 2015;18(1):145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conde-Martínez N., et al. Use of a mixed culture strategy to isolate halophilic bacteria with antibacterial and cytotoxic activity from the Manaure solar saltern in Colombia. BMC Microbiology. 2017;17(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Díaz De Rienzo M.A., et al. Antibacterial properties of biosurfactants against selected Gram-positive and -negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2016;363(2):fnv224. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv224. fnv224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ndlovu T., et al. Characterisation and antimicrobial activity of biosurfactant extracts produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a wastewater treatment plant. AMB Express. 2017;7:108. doi: 10.1186/s13568-017-0363-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mani P., et al. Antimicrobial activities of a promising glycolipid biosurfactant from a novel marine Staphylococcussaprophyticus SBPS 15. 3 Biotech. 2016;6(2):163. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambanthamoorthy K., et al. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm potential of biosurfactants isolated from lactobacilli against multi-drug-resistant pathogens. BMC Microbiology. 2014;14:197. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gudiña E.J., et al. Antimicrobial and antiadhesive properties of a biosurfactant isolated from Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei A20. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2010;50(4):419–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thimon L., et al. Effect of the lipopeptide antibiotic, iturin A, on morphology and membrane ultrastructure of yeast cells. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1995;128(2):101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]