Abstract

Background and objectives

Living kidney donor candidates accept a range of risks and benefits when they decide to proceed with nephrectomy. Informed consent around this decision assumes they receive reliable data about outcomes they regard as critical to their decision making. We identified the outcomes most important to living kidney donors and described the reasons for their choices.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Previous donors were purposively sampled from three transplant units in Australia (Sydney and Melbourne) and Canada (Vancouver). In focus groups using the nominal group technique, participants identified outcomes of donation, ranked them in order of importance, and discussed the reasons for their preferences. An importance score was calculated for each outcome. Qualitative data were analyzed thematically.

Results

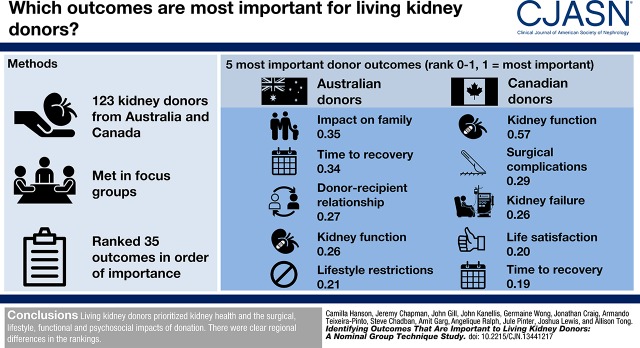

Across 14 groups, 123 donors aged 27–78 years identified 35 outcomes. Across all participants, the ten highest ranked outcomes were kidney function (importance=0.40, scale 0–1), time to recovery (0.27), surgical complications (0.24), effect on family (0.22), donor-recipient relationship (0.21), life satisfaction (0.18), lifestyle restrictions (0.18), kidney failure (0.14), mortality (0.13), and acute pain/discomfort (0.12). Kidney function and kidney failure were more important to Canadian participants, compared with Australian donors. The themes identified included worthwhile sacrifice, insignificance of risks and harms, confidence and empowerment, unfulfilled expectations, and heightened susceptibility.

Conclusions

Living kidney donors prioritized a range of outcomes, with the most important being kidney health and the surgical, lifestyle, functional, and psychosocial effects of donation. Donors also valued improvements to their family life and donor-recipient relationship. There were clear regional differences in the rankings.

Keywords: Acute Pain, Australia, Canada, Decision Making, Focus Groups, Informed Consent, Kidney Donors, Life Style, Living Donors, Nephrectomy, Nominal Group Technique, outcomes, Personal Satisfaction, Qualitative Research, Renal Insufficiency, Risk Assessment

Introduction

In 2014, living kidney donor transplants comprised 42% of kidney transplants performed worldwide (1). Living kidney donor transplantation has been widely advocated to address the global shortage of organs, and can offer transplant recipients superior graft and survival outcomes compared with a deceased donor transplant (2,3). Although there are significant benefits for recipients, living kidney donors must accept various risks associated with nephrectomy.

Living donation is considered ethically justified on the proviso that donors undergo rigorous medical screening and assessment, provide informed and voluntary consent after education about the potential risks and uncertainty regarding long-term outcomes, and have access to long-term health care (4–6). Understanding of the medical risks to living kidney donors is evolving, with the progressive publication of more robust long-term data (7–9). Recent evidence of small absolute increases in the risk of ESKD, hypertension, hypertension in pregnancy, and all-cause mortality in donors in the three decades after donation, compared with the general or healthy population (4,7,8,10–13), reinforces the need for ongoing research and follow-up of living kidney donors.

Living kidney donors experience a broad range of postdonation outcomes that span physical and mental aspects of their health, function, relationships, wellbeing, and livelihood (14). Current guidelines for informed consent and follow-up care do not comprehensively address psychosocial outcomes and other donor-reported outcomes that are relevant to decision making (14–17). This study aims to identify the effects of kidney donation that are deemed important by living kidney donors, and to understand the beliefs underpinning the outcomes they value. This can inform the design of prospective studies evaluating living kidney donor outcomes, and help to ensure that information and follow-up care addresses outcomes that are meaningful and relevant to kidney donors.

Materials and Methods

Participant Recruitment and Selection

We recruited donors from three transplant units in Australia (Sydney, Melbourne) and Canada (Vancouver). Participants were purposively sampled to include a range of demographic (sex, age) and donation characteristics (time since donation, relationship with the recipient, complications). Although we sought to achieve a mix of age and sex in each group where possible, we also considered the participants’ availability. All adult kidney donors from the past 20 years, at the participating units, who were English-speaking, and able to provide informed consent, were eligible to participate. Participants were reimbursed Australian/Canadian $50 for their travel expenses. Ethics approval was obtained from the Western Sydney Local Health District, Monash Health, and the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care.

Data Collection

We conducted focus groups using the nominal group technique, which involved structured “brainstorming” to develop a list of outcomes, followed by individual voting on the outcomes (18). Participants were provided an information sheet before attending the group, but were not asked to come up with a list of outcomes in advance. The 2-hour meetings were convened between July of 2015 and July of 2016 and included four phases: (1) discussion about the experience of kidney donation; (2) individual and group identification of outcomes (augmented with outcomes from previous groups and research studies after participants felt unable to suggest further outcomes) (7,8,11,14,19–25); (3) independent ranking of the relative importance of each outcome; and (4) group discussion of the reasons for their rankings and divergent and similar opinions within the group (26–28) (see Supplemental Material). Three researchers (C.S.H., A.F.R., or A.T.) facilitated the groups in a centrally located venue external to the participating hospitals. An observer (C.S.H., A.F.R., A.T., and J.P.) recorded field notes during the discussion. Each session was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Recruitment was stopped upon reaching data saturation, i.e., when no new concepts were raised in subsequent groups.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis.

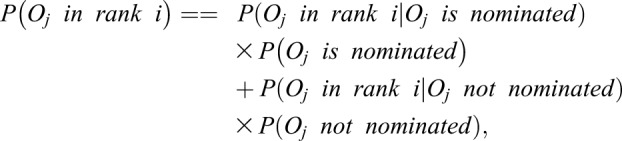

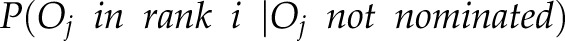

The ranking from the nominal groups produced ordinal data. Some groups did not raise a particular outcome, and some participants did not rank all of the outcomes on the group list. Therefore, it was not appropriate to calculate means. A measure of importance (i.e., importance score) of each outcome was used to prioritize the outcomes, on the basis of the rankings attributed by participants. To calculate this measure, the distribution of the ranking for each outcome was obtained, by calculating the probability of each rank for each outcome ( , i.e., the probability of the outcome Oj being assigned the rank first place, second place, and so on). By the total law of probabilities:

, i.e., the probability of the outcome Oj being assigned the rank first place, second place, and so on). By the total law of probabilities:

|

(1) |

where “nominated” means that the outcome was considered (and given a rank) by the participant. We assumed that the  is 0, because if the participant did not rank the outcome

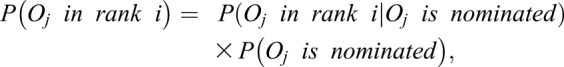

is 0, because if the participant did not rank the outcome  , then the probability of any rank is 0. Therefore, the equation is simplified to:

, then the probability of any rank is 0. Therefore, the equation is simplified to:

|

(2) |

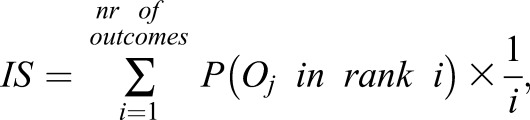

The probability therefore has two components: (1) the importance given to the outcome by the ranking and (2) the consistency of being nominated by the participants. We computed the weighted sum of the inverted ranking  to obtain the importance score.

to obtain the importance score.

|

(3) |

The importance score can be interpreted as a summary measure of importance of the outcome that incorporates the consistency of being nominated and the rankings given by the participants. The ranks are inverted so that more weight is given to top ranks and less to lower ranks. Higher scores identify outcomes that are more valued by the participants. Scores range between zero and one. This measure has a similar motivation to the Expected Reciprocal Rank Evaluation Metric that was proposed in a different context (29). The analysis was conducted using the software package R version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Importance scores for all identified outcomes are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Qualitative Analysis.

We entered the transcripts into HyperRESEARCH (Version 3.5.2; ResearchWare Inc., www.researchware.com) and used an adapted grounded theory approach (30) to inductively identify preliminary concepts and themes. Accordingly, C.S.H. conducted line-by-line coding, assigning codes to meaningful segments of text. Comparisons were made within and across groups, identifying similar and divergent concepts in the data to develop preliminary themes. These preliminary findings were discussed among the research team (investigator triangulation) to consolidate the list of themes and subthemes, and ensure they captured the range and breadth of the participants’ reasons for their rankings.

Results

Participant Characteristics

In total, 123 people aged 27–78 years (mean 55 years, SD=11.5) participated across 14 groups (median=9 participants per group, IQR=8–10, min=5, max=12). Sixty-seven participants were recruited in Australia, and fifty-six from Canada (Supplemental Table 2). The time since donation ranged from 2 months to 16 years (mean 3.6 years, SD=3.1). Demographic and donation characteristics are provided in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Seventy-eight (63%) participants were women, and 100 (81%) were white. The sample included 69 (56%) related donors (child, sibling, parent), 39 (32%) spouses, nine (7%) unrelated donors (colleague, friend), and six (5%) nondirected donors, from Canada. Nineteen (15%) donated through a kidney paired donation. Thirty-one participants (25%) reported mental or physical outcomes which they attributed to the donation (Table 2). No participants reported ESKD.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants (n=123)

| Characteristics | Australia, n=67 (%) | Canada, n=56 (%) | All, n=123 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 41 (61) | 37 (66) | 78 (63) |

| Male | 26 (39) | 19 (34) | 45 (37) |

| Age, yra,e | |||

| 20–29 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 30–39 | 6 (9) | 5 (9) | 11 (9) |

| 40–49 | 15 (22) | 12 (21) | 27 (22) |

| 50–59 | 22 (33) | 14 (25) | 36 (29) |

| 60–69 | 15 (22) | 19 (34) | 34 (28) |

| 70–79 | 8 (12) | 5 (9) | 13 (11) |

| Race/ethnicitya | |||

| White | 56 (84) | 44 (79) | 100 (81) |

| Asian | 5 (7) | 7 (13) | 12 (10) |

| Middle Eastern | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) |

| Otherb | 1 (1) | 5 (9) | 6 (5) |

| Highest level of educationa | |||

| University degree | 25 (37) | 35 (62) | 60 (49) |

| Diploma/certificate | 15 (22) | 10 (18) | 25 (20) |

| Secondary school: year 12 | 9 (13) | 11 (20) | 20 (16) |

| Secondary school: year 10 | 17 (25) | 0 (0) | 17 (14) |

| Total household income per year (USD)a,c | |||

| $0–$32,135 | 15 (22) | 1 (2) | 16 (13) |

| $32,136–$66,949 | 16 (24) | 13 (23) | 29 (24) |

| $66,950–$107,120 | 15 (22) | 15 (27) | 30 (24) |

| >$107,120 | 16 (24) | 26 (46) | 42 (34) |

| Employment statusa | |||

| Full time | 35 (52) | 33 (59) | 68 (55) |

| Part time/casual | 15 (22) | 7 (13) | 22 (18) |

| Retired/pensioner | 12 (18) | 12 (21) | 24 (20) |

| Not employed | 4 (6) | 3 (5) | 7 (6) |

| Marital statusa | |||

| Married/de facto relationshipd | 57 (85) | 39 (70) | 96 (78) |

| Divorced | 0 (0) | 7 (13) | 7 (6) |

| Widowed | 5 (7) | 1 (2) | 6 (5) |

| Separated | 1 (1) | 5 (9) | 6 (5) |

| Single | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 5 (4) |

| Partner (not living with) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

USD, US dollars.

Total N≠123 due to nonresponse.

Includes South American, African, Pacific Islander, and First Nation (Canada).

As defined by Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 Census Survey, converted to USD using average 2011 exchange rate.

Living together as a couple.

In 2016, 14% of kidney donors in Canada were aged >60 (42).

Table 2.

Donation and health characteristics of the participants (n=123)

| Characteristics | Australia (n=67) | Canada (n=56) | All, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time since donation, yra | |||

| <1 | 3 (4) | 9 (16) | 12 (10) |

| 1–3 | 26 (39) | 28 (50) | 54 (44) |

| 4–6 | 16 (24) | 16 (29) | 32 (26) |

| 7–10 | 7 (10) | 2 (4) | 9 (7) |

| >10 | 6 (9) | 0 (0) | 6 (5) |

| Relationship to recipientb | |||

| Spouse | 28 (42) | 11 (20) | 39 (32) |

| Parent | 17 (25) | 16 (29) | 33 (27) |

| Sibling | 15 (22) | 8 (14) | 23 (19) |

| Friend/colleague | 2 (3) | 7 (13) | 9 (7) |

| Child | 2 (3) | 4 (7) | 6 (5) |

| Other relative | 3 (4) | 4 (7) | 7 (6) |

| Nondirected (anonymous) | 0 (0) | 6 (11) | 6 (5) |

| Kidney paired donation | |||

| Yes | 9 (13) | 10 (18) | 19 (15) |

| No | 58 (87) | 46 (82) | 104 (85) |

| Recipient outcomec | |||

| Alive and functioning graft | 61 (91) | 52 (93) | 113 (92) |

| Graft failure or death | 6 (9) | 4 (7) | 10 (8) |

| Self-reported postdonation complications | |||

| Any | 19 (28) | 12 (21) | 31 (25) |

| Mental health | 5 (7) | 3 (5) | 8 (7) |

| Hypertension | 5 (7) | 2 (4) | 7 (6) |

| Chronic pain | 1 (1) | 2 (4) | 3 (2) |

| Hydrocele | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Otherd | 8 (12) | 5 (9) | 13 (11) |

Total N≠123 due to nonresponse.

The timing of the recipient outcome was not captured.

Includes hyperthyroidism, low BP, kidney stones, gall stones, hernia, blood clots, endometriosis, gout, high cholesterol, scleritis, and osteoporosis. Note that acute pain and fatigue were not reported as complications, despite being indicated in qualitative data.

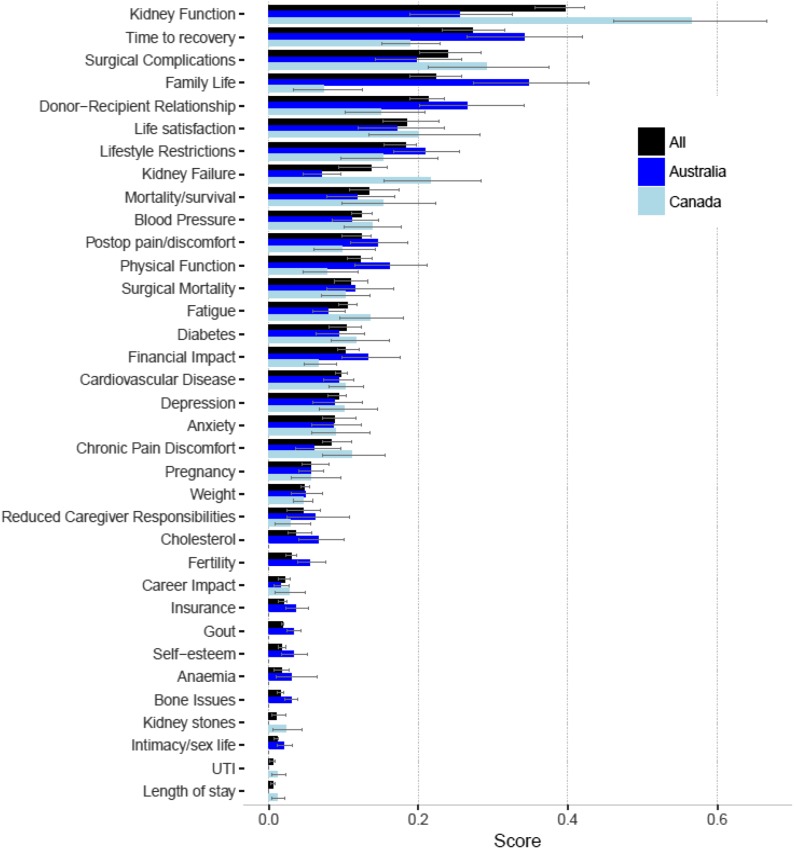

Nominal Group Ranking

The participants identified a combined total of 35 postdonation outcomes and the mean number of outcomes identified by each group was 22 (SD=3.0, range 19–28). The importance scores for donor outcomes across all participants, stratified by country, are shown in Figure 1. Across all participants, the ten highest ranked outcomes were kidney function (i.e., GFR and creatinine levels) (importance=0.40), time to recovery (0.27), surgical complications (0.24), effect on family (0.22), donor-recipient relationship (0.21), life satisfaction (0.18), lifestyle restrictions (0.18), kidney failure (0.14), mortality (0.13), and acute pain/discomfort (0.12) (Supplemental Table 1). Differences in ranking between Canadian and Australian participants are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Importance scores for donor outcomes by country. The five most important donor outcomes for Australian participants were effect on family (importance score=0.35, scale 0–1), followed by time to recovery (0.34), donor-recipient relationship (0.27), kidney function (0.26), and lifestyle restrictions (0.21). The five most important donor outcomes for Canadian participants were kidney function (0.57), followed by surgical complications (0.29), kidney failure (0.22), life satisfaction (0.20), and time to recovery (0.19). Postop, postoperative; UTI, urinary tract infection.

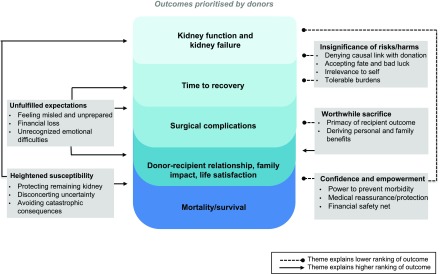

Qualitative Analysis

We identified five themes that explained participants’ ranking of outcomes. Quotations to illustrate each theme are provided in Table 3. Figure 2 provides a conceptual schema of the relationship between themes and the ranking of outcomes.

Table 3.

Illustrative quotations

| Theme | Illustrative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Worthwhile sacrifice | |

| Primacy of recipient outcome | “One of the key ones for me is the success of the donation for the (recipient). Had it been negative or there had been problems it would have been very emotional.” (Woman, Canada, 40s) |

| “They’re all important it’s just hard to pick one as long as whoever is getting the kidney is okay …” (Woman, Australia, 50s) | |

| “When that fails, you're no longer in control of that person's health, and therefore you would feel a sense of blame, maybe? And helplessness, yeah.” (Woman, Australia, 50s) | |

| Deriving personal and familial benefits | “My top one was family life, as long as all that’s fine everything else will be fine.” (Woman, Australia, 70s) |

| “Ever since then we have been travelling all over the world. So freedom! The freedom is amazing so that is really important to us.” (Woman, Canada, 50s) | |

| Insignificance of risks and harms | |

| Tolerable burdens and sacrifices | “I mean, I am now never going to be a professional kick-boxer. There are some things that you’re taking out of your life as options.” (Woman, Canada, 30s) |

| “But I’d like the media, or the general public to know that it’s not hard … just the recovery period.” (Man, Canada, 60s) | |

| “Yeah, just a little bit of the recovery but, you forget about that after a while.” (Man, Canada, 70s) | |

| “As we all said we’ll do it again no matter what the outcome was.” (Woman, Australia, 50s) | |

| “Even now I still don’t get any feeling in my arm when I wake up. It is disturbing. I don’t make a big deal of it because I donated my kidney to my sister and I don’t want her to think that my lifestyle has changed.” (Woman, Canada, 40s) | |

| Irrelevance to self | “You can feel the points; they were 6, 12 mo, and then the 2 yr. And after that it's like it never happened.” (Man, Australia, 60s) |

| “I wasn’t really worried about any of the outcomes. I knew I was a healthy individual. I didn’t really have any concerns.” (Woman, Canada, 40s) | |

| “I haven’t lived with (chronic pain). So it’s hard for me to say because you don’t know what that is until you experience it. So beforehand, I don’t think it would’ve made a difference to me.” (Woman, Australia, 60s) | |

| Denying causation | “But quite a lot of those things, I’ve got, but it’s nothing to do with my kidney I would think. I think it’s because of my age. Postmenopausal.” (Woman, Australia, 70s) |

| “But I mean like you could develop it later in life, like type 2 diabetes, if you have like a poor diet or whatever. If you’re going to make poor choices in your life, are you going to have a worse outcome if you have one kidney or two kidneys, right?” (Man, Canada, 50s) | |

| “Weighted risk compared to other things like smoking and high BP seems to like, far outweigh the kidney thing, so I wouldn’t be concerned about it.” (Man, Canada, 60s) | |

| Accepting fate and bad luck | “I got a massive hernia, so I had to go back in for another 5 d and have that repaired and (I’ve got another one) … But they just said I was just one of the unluckiest ones they’d had, so but it wouldn’t have changed my decision to do it. It’s just that it was damn unlucky. Very unexpected. They got fright too.” (Woman, Australia, 60s) |

| “If it is your time it is your time and you cannot stop it right? You can die crossing the street … When it is your time, it is your time, never thought about it …” (Man, Canada, 40s) | |

| “Because I read that (risk of kidney failure) in the literature before I had the operation, you know, but at the end of day, you just can’t afford to think about that.” (Man, Australia, 70s) | |

| Confidence and empowerment | |

| Power to prevent morbidity | “I am actually healthier now just because I have had this on my mind. So I eat healthier, exercise more and so I feel like health wise it has been beneficial.” (Woman, Canada, 50s) |

| “I was of the impression that if you kept your BP down, you didn’t have diabetes and you didn’t have high cholesterol and you have average weight that there’d be no problems with kidney function.” (Woman, Australia, 50s) | |

| Medical reassurance and protection | “For the rest, they already screened us, so I think if I was going to be worried about all of these, I’m not because they screened me for it. Like I have enough faith in the prework that I’m not going to sweat it now. So it’s done, I’m not going to worry about it or second guess medicine.” (Man, Canada, 50s) |

| “The longer the years go on, the longer statistical window they have, but the statistics they brought up to me were all very positive. So it was, again, another nonissue.” (Man, Canada, 60s) | |

| “Well I remember the surgeon told me there’s no proof at all that says somebody with two kidneys lives any longer than someone with one.” (Man, Canada, 50s) | |

| Financial safety net | “Through the organ donation program, they reimbursed all that which was really good. I didn’t lose any of my long service leave … some people can’t have that 8 wk off or they might depend on that one income coming in. Even though it’s important to donate, there are other things as well …” (Woman, Australia, 50s) |

| “I guess I had the luxury of all I had to worry about was getting better, work was paid, I had sick leave and if I was allowed that time off work without issues.” (Man, Australia, 50s) | |

| Unfulfilled expectations | |

| Misled and unprepared | “I don’t regret my decision at all. But I did not have an easy recovery … but I wish I had known it wasn’t as super easy as some people will lead you to believe. And that is why the donor blogs were super helpful because there are some people on there who have had truly awful experiences. And I knew that wasn’t going to be my experience. There were some people on there who had truly amazing experiences and mine ended up somewhere in the middle.” (Woman, Canada, 40s) |

| “What would been interesting if there was some sort of follow-up as to how long you’re in hospital for, what was your recovery like? At what report did you return to full health? All that seems like valuable information. I didn’t really feel that captured at all. If it was recorded in a way that it could be used to better inform people or perhaps maybe target different things for different people. And maybe complications … Information that no one bothers to record.” (Man, Australia, 40s) | |

| “It was really awful and I’ve never had that in my life, and they didn’t warn me about all the digestive stuff. From the nausea to the constipation.” (Woman, Canada, 60s) | |

| “Well lifestyle restrictions. I’ve been healthy all my life, I didn’t have to worry about what I ate or drank or whatever. Now I’m worrying about what medications I can take.” (Woman, Canada, 50s) | |

| “I must admit I feel bad sometimes but you would do it again if you had to, I’m so glad I can’t really. I found it pretty horrible to be honest. I had partial lung collapse and the only way to fix that was to cough.” (Man, Australia, 40s) | |

| “The main thing for me was my sex drive went completely out the window … It was more just the fact that every time I looked down, my guts were smiling back up at me and, it was again, a vanity thing, psychological like, ‘Oh, my God! Look at that. It’s horrific.’” (Man, Australia, 30s) | |

| Unrecognized emotional difficulties | “What I’m saying it as a point of study. Not that I have regret. But it would definitely be interesting to see if people have regret after.” (Woman, Canada, 50s) |

| “It actually surprised me how long it took me to recover. It wasn’t just the physical part of it. It was the emotional and the mental part of it.” (Woman, Canada, 50s) | |

| “I focused on the other ones for the entire opposite reason. It’s easier to manage your scientific stuff. It’s really difficult to quantify emotional and relationship things, and I think that’s a missing part of the research.” (Woman, Canada, 30s) | |

| “It was like, you know how you get the baby blues? On the fourth day, I just lost it … I don’t know whether it’s because I lost this thing and I just fell to pieces.” (Woman, Australia, 50s) | |

| “I think for me after I donated a kidney, I got depression for a few months. It took me probably a year to feel better, and I started gaining a lot of weight and I didn’t have any energy. I wasn’t feeling happy. I mean I was feeling happy for my daughter but no, inside me I wasn’t happy.” (Woman, Canada, 30s) | |

| “I was surprised to hear that you suffered depression. I wasn’t told that that could be an impact and I think that’s really crucial. People really need to know that that’s a possibility. I don’t remember them saying anything about it … But if it does happen it can be quite, I would imagine, very discombobulating.” (Woman, Canada, 50s) | |

| “It seemed to me that stuff like kidney function, cardiovascular disease, ESKD, diabetes, all those things with a disease on them will probably be studied or come up in other studies. It seemed to me that I was choosing stuff that probably wouldn’t necessarily be studied.” (Man, Canada, 60s) | |

| “If my husband's kidney failed, I'm not sure how I'd react to that. Right now he's doing extremely well. But if something should happen to him, would I be exposed to this depression and anxiety? That would worry me.” (Woman, Canada, 50s) | |

| “I had a lot of bloating. I had a lot of pain and that went on years. I think they now know that (the surgeon) cut a nerve. But all this has really gotten me down a lot.” (Woman, Australia, 50s) | |

| “I don’t regret it. But I’m not fine. I’m not 100%. It’s a frustrating position to be in because I don’t fit what the ranges are … I definitely felt there was an expectation that I wouldn’t have any needs past 6 wk. It was a magical number.” (Woman, Canada, 40s) | |

| “Number two would be chronic pain/numbness because I’m still suffering from the after effects of that complication, every day. It’s not serious right now but I’m afraid it might get worse. I don’t know what to expect.” (Woman, Canada, 50s) | |

| “I mean I don’t feel good about it, having a medical condition. You know I’m happy to help somebody but I was a healthy person, and now I’m stuck with this … Probably not. I wouldn’t have done it … if I’m harming my health and I have to live the rest of my life like this … It’s really quite intense.” (Man, Canada, 50s) | |

| “For me, what I’d like to know. They are very good at the beginning at telling you this should happen. This should happen. Afterwards, my feeling on it, was they didn’t really follow-up with you and say did that happen? Did that happen in your case? They said the percentages of whatever, but am I one of those percentages?” (Woman, Canada, 30s) | |

| Financial loss | “For me it was absolute destruction. Bankruptcy. I was off for a year … But you know, it is embarrassing to tell the family that …” (Man, Canada, 60s) |

| “That had a bit of an impact, we didn’t get any money back for the medication because I had to get medication and whatnot, I had to pay for all that.” (Man, Australia, 30s) | |

| “I was actually fired for the amount of time that I was about to take off … apart from the actual firing itself, I found it very hard after the recovery of about 2 mo to get another job. People just didn’t want to look at me. It was the weirdest thing ever.” (Man, Australia, 30s) | |

| Heightened susceptibility | |

| Protecting the remaining kidney | “'Because there seems to be, just in my mind anyway, some sort of connection between kidneys and particularly diabetes and BP. And I'm not sure which is the chicken and which is the egg?” (Man, Australia, 70s) |

| “It’s not so much function. It’s, can you preserve or enhance your kidney health as a result of diet … I just got told to keep doing what I was doing, whatever that is …” (Man, Canada, 40s) | |

| Avoiding catastrophic consequences | “Your mortality is not just about yourself, it's about your family or the family that you're going to have.” (Man, Australia, 40s) |

| “So, number one was surgical complications, number two kidney failure, number three cardiovascular disease. I suppose they are, the most serious things … They’re not necessarily the things that impacted me the most but they would be the things that if I was looking to donate a kidney, I would want to know that those things are going to be okay.” (Woman, Australia, 40s) | |

| “I mean it was top ten because I have kids … I worry about diabetes because I don’t want both of us going for dialysis. That’s the only reason why I worry, it’s not my self-preservation but more for family worry.” (Woman, Canada, 30s) | |

| Disconcerting uncertainty | “We’re all adding to the data pool with our annual lab requisitions, but we don’t hear back as a group on the overall experience. You’ve got a mass of data there, it’s easy enough to manipulate, and an incoming donor should have access to that information. Like on average, your GFR will go down to whatever, and you can rank that based on the demographic … you’ve got a pool of information that should be mined.” (Man, Canada, 60s) |

| “Now that I think on it, one of my biggest concerns afterwards was what would be the long-term repercussions because back at the time we did our transplant, there was no ruling data on long term impacts …” (Man, Australia, 50s) | |

| “Is there any study, is there any data the impact of donation on the life expectancy of donors? Is there any statistic? Do we know anything about that? Is that one of the things that could be kind of explored so there’s information? It helps towards making an informed decision if people are assessing all sorts of things.” (Woman, Canada, 70s) | |

Figure 2.

Themes underpinning the importance of outcomes of donation to donors. Concern for their heightened susceptibility to kidney disease led participants to prioritize kidney function, kidney failure, and survival. However, confidence and empowerment to protect their health, and the perceived insignificance and irrelevance of risks and harms, underpinned the lower ranking of these outcomes for some donors. They considered their sacrifice to be worthwhile because of the psychosocial benefits they received and improvement to the recipient’s quality of life; surgical complications were therefore considered tolerable and of lower significance for some donors. However, some participants ranked surgical complications and functional impairment high because they had unfulfilled expectations regarding these outcomes, feeling misled, unprepared, or that these issues were not addressed in follow-up.

Worthwhile Sacrifice.

Primacy of Recipient Outcome.

Participants’ satisfaction with the donation depended primarily on the outcome for the recipient. Recipient graft failure was expected to feel “similar to a stillbirth,” accompanied by guilt, and “helplessness” because “you’ve got no kidney left to give.” Surgical complications and lifestyle restrictions were considered “totally worth it,” given the improvements in their recipients’ health. Donors declared that they concealed their complications to avoid being “selfish” or making the recipient feel guilty.

Deriving Personal and Familial Benefits.

Related donors valued the improvement to their own wellbeing, family life, and relationship with the recipient, because these outcomes had motivated them to donate. For some participants, these positive outcomes were the only effects they had experienced. However, other participants ranked these outcomes lower because they felt these psychosocial benefits were “implicit,” “subjective,” and difficult to measure.

Insignificance of Risks and Harms.

Tolerable Burdens and Sacrifices.

Some participants were less concerned with short-term or non–life-threatening outcomes like pain because these were expected or they could “tough out those ones.” The ease of their recovery surprised some participants, and they wanted these outcomes recorded to reassure potential donors.

Irrelevance to Self.

After full recovery, some participants experienced no perceptible effects of donating a kidney (“it’s like it never happened”) and some believed their health had improved due to their adoption of a healthy lifestyle. Therefore, long-term health outcomes seemed irrelevant.

Denying Causation.

Some participants questioned whether conditions they had developed after donation, such as gout and hypertension, were caused by their lifestyle, preexisting circumstances, or age, rather than the donation. Some participants did not believe the nephrectomy would increase their risk of developing ESKD, and instead attributed this outcome to a “bad” lifestyle.

Accepting Fate and Bad Luck.

Participants were reluctant to consider hypothetic repercussions of their nephrectomy because “there’s no going back.” Older participants believed that they would inevitably develop health complications due to age. Surgical complications were viewed as “bad luck” and some ranked this low to avoid “put(ting) people off.”

Confidence and Empowerment.

Power to Prevent Morbidity.

Participants believed that they could actively prevent kidney disease and cardiovascular disease by managing their diet, weight, cholesterol, and BP. Some ranked psychologic outcomes lower because these were “within (their) own control.”

Medical Reassurance and Protection.

The “stringent” predonation assessment gave participants confidence that their health was “not an issue”—“I’m not going to second guess medicine.” They recalled “very positive” statistics about mortality and long-term outcomes. The promise of transplant wait-listing priority in Canada somewhat reassured participants about ESKD.

Financial Safety Net.

Many participants had a financial buffer or assistance to help them absorb out-of-pocket expenses and replace lost income as a result of donation, thus they ranked this lower.

Unfulfilled Expectations.

Financial Loss.

Other participants ranked financial effect highly because they believed that lost income and out-of-pocket expenses were unfair barriers to donors. For younger donors, single parents, and the donor who was not a resident and uninsured, the costs were “a big hit” and, for one, “an absolute destruction.” The leave required for recovery caused some donors to lose their jobs.

Misled and Unprepared.

Some participants ranked time to recovery, surgical complications, and pain highly because they felt “deeply disappointed” and “resentful” about enduring a more debilitating and protracted recovery than they had been “led to expect.” They considered a full recovery to mean “to be back to your life.” Participants had vivid memories of “excruciating” postoperative pain. Younger participants were frustrated by being unable to resume physical activity and some noticed that their self-esteem and sex drive diminished, during recovery.

Unrecognized Emotional Difficulties.

Donors felt that persistent complications (e.g., pain, fatigue, and seromas) were overlooked by their clinicians. Some experienced a difficult emotional recovery due to their physical incapacitation, or a sense of loss—“I was surprised by how low I felt for a while.” Participants also described worry about their recipient’s graft function, the devastation of recipient death or graft failure, their discomfort with their “hero status” among their social network, lack of support from family members, and complexities in their relationship with the recipient.

Heightened Susceptibility.

Avoiding Catastrophic Consequences.

Surgical mortality, life-expectancy, and morbidity were important, particularly during decision-making, because they were the “most serious” outcomes which would also affect their family. Participants were focused on their kidney function due to a fear of kidney failure. This was concerning for younger donors—“I’m thirty-one, I’ve got a lot of years to come.” Hypothetic long-term outcomes were “not necessarily the things that impacted them the most,” and therefore ranked lower for some. Nondirected donors’ “own health was most important” because they “didn’t know anything about (the) recipient.”

Protecting the Remaining Kidney.

In the short-term period after donation, some participants felt “paranoid” about their kidney function, and were concerned whether their GFR was “normal.” “Lifestyle restrictions” were important because they wanted greater understanding of harmful activities, diets, and medicines so they could protect their long-term kidney function. Diabetes and hypertension were of concern because they were perceived precursors to kidney failure.

Disconcerting Uncertainty.

A few participants, from both countries, expressed concern regarding the lack of long-term data on ESKD and mortality. They considered further research imperative to gain a “longer statistical window,” to “confirm” the safety of donation. Participants also wanted answers to their unexplained complications, such as fatigue, so felt these were important for research.

Discussion

Postdonation outcomes that were most important to kidney donors included long-term health outcomes (kidney function and kidney failure), surgical and functional outcomes (postoperative recovery, surgical complications, pain, and physical function), and psychosocial effects (effect on family, donor-recipient relationship, and life satisfaction). Donors were concerned about their kidney health and some were disappointed by unmet expectations regarding their recovery, physical function, relationships, and psychologic wellbeing. Although their priorities were largely on the basis of the outcomes they experienced of donation, some donors downplayed short-lived problems, perceiving pain and fatigue to be tolerable burdens in light of the improvements to their family life, relationship, and their recipient’s health. The hypothetic long-term risks associated with nephrectomy, including mortality and cardiovascular disease, were of relatively lower importance. Although some donors were concerned about their heightened susceptibility to morbidity and mortality, most donors believed their clinicians had ruled out long-term risks through screening, and believed they were able to prevent disease through a healthy lifestyle and maintaining their kidney function.

There were some differences observed in the importance of outcomes between donors recruited from Australia and Canada. Canadian donors ranked kidney function and failure higher than Australian participants, who ranked time to recovery, physical function, effect on family, donor-recipient relationship, and financial effect higher. A few participants in both countries expressed concerns about their heightened susceptibility to kidney failure. This may have been ranked higher among the Canadian sample, because of the inclusion of nondirected donors and more unrelated donors, who focus more on their own health compared with the recipient. There may also be an era effect, because most Canadian participants were more recent donors, after literature on ESKD risk had been published. The clinicians in Vancouver may emphasize these outcomes differently to donors. The Canadian cohort also had a higher proportion of tertiary educated people. The percentage of participants who reported complications was higher for Australian participants than Canadian participants (Table 2), perhaps explaining the higher ranking of physical function and time to recovery. Financial effect may have been more important to Australian donors because 60% donated before the introduction of the Support for Living Organ Donors Program, in 2013. Canadian participants donated after a reimbursement program was available in British Columbia.

Kidney function was the highest ranked outcome, underpinned by a fear of developing kidney failure. Monitoring their kidney function gave donors reassurance that they could prevent the onset of kidney failure. Donors were uncertain whether their GFR after donation was “normal” and how to modify their lifestyle and diet to protect their long-term kidney function. On the one hand, many donors felt that they had ruled out risks of kidney failure during assessment, and were focused on the outcomes they experienced rather than hypothetic long-term outcomes. However, some expressed concerns about developing kidney failure, particularly younger and more recent donors. Anxiety about kidney failure has been found to be common among donors within 10 years of donation (31).

Psychosocial, physical functioning, and surgical complications were also highly important to donors. Previous studies suggest that only a minority of donors (5%–25%) report negative psychosocial and physical outcomes (21,32–34). A recent registry study from the United States found that 17% of donors experienced a perioperative complication; however, 3% experienced major complications (35). However, donors prioritized these outcomes because they were often unexpected and unaddressed in follow-up. This caused donors to feel unprepared, misled, and unsupported after donation.

We recruited donors from two countries with various donation characteristics. The mixed-methods design generated comprehensive data about donors’ priorities and perspectives regarding donation outcomes. Whereas surveys with donors are susceptible to social desirability bias, inhibiting discussion of negative outcomes (21), the focus group enabled open communication due to the shared experiences among participants. However, there are limitations to our study. Our sample was limited to English-speaking participants who were 81% white and attained a high level of education. Importantly, donors from Australia and Canada have access to universal health coverage. Therefore, the transferability of our findings may be limited in some countries and programs. Because of the semistructured nature of the nominal group technique, each group generated a different list of outcomes. The importance score incorporated the ranking and the consideration of the outcome. We included donors, who were 2 months to 16 years postdonation, but we were unable to assess how donors’ priorities might change over time. Potential donors who were excluded or chose not to donate were not included in our study and may have different perspectives on outcomes. For example, the financial effect, perioperative health risks, and the potential effect on childbearing were identified as reasons for opting out by nondonors (36). These findings may inform larger scale surveys whereby the importance of donor outcomes may be assessed in a larger population that would not be feasible in the mixed-method nominal group technique study (14).

Our findings suggest there is a need to improve donors’ understanding of long-term outcomes, but also improve education and follow-up care around the outcomes that are important to each donor. Informed consent practices have been shown to vary widely across centers, particularly in terms of the information provided and use of methods to assess voluntariness and comprehension of information (37). The recent Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines recommend informing donors of individualized risks and benefits including medical, surgical, psychosocial, and economic outcomes (6). They suggest communicating absolute risks and disclosing uncertainty in long-term outcomes (6). However, donors’ strong motivations and the confidence in their safety pose additional barriers to comprehending information before donation (38–40). Continued education about donor outcomes and emerging evidence is therefore critical after donation.

The assessment of donor-reported outcomes can provide information to help prepare donors for a range of outcomes they may experience and care about, and enable follow-up care to be individualized to the donor’s needs (41). The Organ Procurement Transplant Network mandates the collection of data on a range of postdonation outcomes for 2 years after donation, including two psychosocial outcomes—employment status and loss of insurance. A broader scope of psychosocial and functional outcomes should be assessed in follow-up. For example, a validated longer-term measure of recovery is needed, that captures donors’ full recovery. The effect on family, changes to the donor-recipient relationship, life satisfaction, acute pain, physical function, and fatigue were also important outcomes that donors wanted to be informed about. We suggest that these outcomes be included in future research in living kidney donors to inform shared decision-making on the basis of outcomes that are relevant, meaningful, and important to donors.

Living kidney donors were concerned about their kidney health and the surgical, lifestyle, and psychosocial effects of donation that were unexpected, debilitating, or unaddressed in postdonation follow-up care. They also valued improvements to their emotional wellbeing, effect on family, and donor-recipient relationship. These findings emphasize the importance of identifying donors’ priorities and concerns during the informed consent process, and being cognizant of the donor’s confidence in the transplant process such that they may readily accept or disregard long-term health risks. The assessment of donor-important outcomes during follow-up, the collection of more robust data on long-term outcomes, and efforts to keep donors informed of emerging evidence on donor outcomes and protective lifestyle behaviors could improve donor satisfaction and wellbeing after donation, and reduce their anxieties about their vulnerability to kidney disease. Our findings can provide a framework to ensure that the outcomes most relevant to donors are consistently included in research, education, assessment, and follow-up care.

Disclosures

C.S.H. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Postgraduate Scholarship (GNT1092741). A.T. is supported by an NHMRC Fellowship (1106716). J.R.L. is supported by an NHMRC Fellowship (1107474). A.X.G. is supported by the Doctor Adam Linton Chair in Kidney Health Analytics and a Clinician Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The project is funded by an Australian Research Council Grant (DE120101710). The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval or the manuscript. C.S.H., J.R.C., J.S.G., J.K., G.W., J.C.C., S.J.C., A.X.G., A.F.R., J.P., J.R.L., and A.T. declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the living kidney donors who generously gave their time to share their insights and perspectives.

Research idea and study design: C.S.H., J.R.C., J.S.G., J.K., G.W., J.C.C., A.T.-P., S.J.C., A.X.G., A.F.R., J.P., J.R.L., and A.T.; data acquisition: C.S.H., J.P., A.F.R., and A.T.; data analysis/interpretation: C.S.H., J.R.C., A.T.-P., J.S.G., J.K., G.W., J.C.C., S.J.C., A.X.G., A.F.R., J.P., J.R.L., and A.T.; statistical analysis: C.S.H., J.C.C., A.T.P., and A.T.; supervision and mentorship: J.C.C. and A.T. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related Patient Voice and editorial, “Living Donation: The Donors and Recipient Perspectives,” and “Donor Outcomes: Why We Need to Listen,” on pages 823–824 and 831–832, respectively.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13441217/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation: Organ donation and transplantation activities, 2014. Available at: http://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-reports-2014/. Accessed January 1, 2014

- 2.Terasaki PI, Cecka JM, Gjertson DW, Takemoto S: High survival rates of kidney transplants from spousal and living unrelated donors. N Engl J Med 333: 333–336, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molnar MZ, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Shah A, Huang E, Bunnapradist S, Krishnan M, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Age and the associations of living donor and expanded criteria donor kidneys with kidney transplant outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 841–848, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaston RS, Kumar V, Matas AJ: Reassessing medical risk in living kidney donors. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1017–1019, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reese PP, Boudville N, Garg AX: Living kidney donation: Outcomes, ethics, and uncertainty. Lancet 385: 2003–2013, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lentine KL, Kasiske BL, Levey AS, Adams PL, Alberú J, Bakr MA, Gallon L, Garvey CA, Guleria S, Li PK, Segev DL, Taler SJ, Tanabe K, Wright L, Zeier MG, Cheung M, Garg AX: KDIGO clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and care of living kidney donors. Transplantation 101[8S]: S7–S105, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, Foss A, Midtvedt K, Øyen O, Reisæter A, Pfeffer P, Jenssen T, Leivestad T, Line PD, Øvrehus M, Dale DO, Pihlstrøm H, Holme I, Dekker FW, Holdaas H: Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int 86: 162–167, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang M-C, Montgomery RA, McBride MA, Wainright JL, Segev DL: Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA 311: 579–586, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizvi SAH, Zafar MN, Jawad F, Aziz T, Hussain Z, Hashmi A, Hussain M, Akhtar F, Ahmed E, Naqvi R, Naqvi SA: Long-term safety of living kidney donation in an emerging economy. Transplantation 100: 1284–1293, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey P, Edwards A, Courtney AE: Living kidney donation. BMJ 354: i4746, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reese PP, Bloom RD, Feldman HI, Rosenbaum P, Wang W, Saynisch P, Tarsi NM, Mukherjee N, Garg AX, Mussell A, Shults J, Even-Shoshan O, Townsend RR, Silber JH: Mortality and cardiovascular disease among older live kidney donors. Am J Transplant 14: 1853–1861, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg AX, Meirambayeva A, Huang A, Kim J, Prasad GV, Knoll G, Boudville N, Lok C, McFarlane P, Karpinski M, Storsley L, Klarenbach S, Lam N, Thomas SM, Dipchand C, Reese P, Doshi M, Gibney E, Taub K, Young A; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research Network : Cardiovascular disease in kidney donors: matched cohort study. BMJ 344: e1203, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg AX, Nevis IF, McArthur E, Sontrop JM, Koval JJ, Lam NN, Hildebrand AM, Reese PP, Storsley L, Gill JS, Segev DL, Habbous S, Bugeja A, Knoll GA, Dipchand C, Monroy-Cuadros M, Lentine KL; DONOR Network : Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia in living kidney donors. N Engl J Med 372: 124–133, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong A, Chapman JR, Wong G, Kanellis J, McCarthy G, Craig JC: The motivations and experiences of living kidney donors: A thematic synthesis. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 15–26, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen MB, Abt PL, Reese PP: What are the harms of refusing to allow living kidney donation? An expanded view of risks and benefits. Am J Transplant 14: 531–537, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiessen C, Gordon EJ, Reese PP, Kulkarni S: Development of a donor‐centered approach to risk assessment: Rebalancing non‐maleficence and autonomy. Am J Transplant 15: 2314–2323, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Chapman JR, Wong G, de Bruijn J, Craig JC: Screening and follow-up of living kidney donors: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Transplantation 92: 962–972, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen J, Dyas J, Jones M: Building consensus in health care: A guide to using the nominal group technique. Br J Community Nurs 9: 110–114, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boudville N, Prasad GV, Knoll G, Muirhead N, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Yang RC, Rosas-Arellano MP, Housawi A, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network : Meta-analysis: Risk for hypertension in living kidney donors. Ann Intern Med 145: 185–196, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke KS, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, Yang RC, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network : The direct and indirect economic costs incurred by living kidney donors-a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1952–1960, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clemens KK, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Parikh CR, Yang RC, Karley ML, Boudville N, Ramesh Prasad GV, Garg AX; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network : Psychosocial health of living kidney donors: A systematic review. Am J Transplant 6: 2965–2977, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg AX, Muirhead N, Knoll G, Yang RC, Prasad GV, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Housawi A, Boudville N; Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network : Proteinuria and reduced kidney function in living kidney donors: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Kidney Int 70: 1801–1810, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young A, Storsley L, Garg AX, Treleaven D, Nguan CY, Cuerden MS, Karpinski M: Health outcomes for living kidney donors with isolated medical abnormalities: A systematic review. Am J Transplant 8: 1878–1890, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, Mehta SH, Singer AL, Taranto SE, McBride MA, Montgomery RA: Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA 303: 959–966, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, Rogers T, Bailey RF, Guo H, Gross CR, Matas AJ: Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med 360: 459–469, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gargon E, Gurung B, Medley N, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Williamson PR: Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: A systematic review. PLoS One 9: e99111, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howell M, Tong A, Wong G, Craig JC, Howard K: Important outcomes for kidney transplant recipients: A nominal group and qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 186–196, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morton RL, Tong A, Webster AC, Snelling P, Howard K: Characteristics of dialysis important to patients and family caregivers: A mixed methods approach. Nephrol Dial Transpl 26: 4038–4046, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapelle O, Metlzer D, Zhang Y, Grinspan P, editors: Expected reciprocal rank for graded relevance. Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on Information and knowledge management, Hong Kong, China, November 2–6, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaser BG, Strauss AL: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, Piscataway, NJ, Transaction Publishers, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigue JR, Fleishman A, Vishnevsky T, Whiting J, Vella JP, Garrison K, Moore D, Kayler L, Baliga P, Chavin KD, Karp S, Mandelbrot DA: Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess fear of kidney failure following living donation. Transpl Int 27: 570–575, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Timmerman L, Laging M, Westerhof GJ, Timman R, Zuidema WC, Beck DK, IJzermans JN, Betjes MG, Busschbach JJ, Weimar W, Massey EK: Mental health among living kidney donors: A prospective comparison with matched controls from the general population. Am J Transplant 15: 508–517, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith GC, Trauer T, Kerr PG, Chadban SJ: Prospective psychosocial monitoring of living kidney donors using the Short Form-36 health survey: Results at 12 months. Transplantation 78: 1384–1389, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dew MA, Myaskovsky L, Steel JL, DiMartini AF: Managing the psychosocial and financial consequences of living donation. Curr Transplant Rep 1: 24–34, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lentine KL, Lam NN, Axelrod D, Schnitzler MA, Garg AX, Xiao H, Dzebisashvili N, Schold JD, Brennan DC, Randall H, King EA, Segev DL: Perioperative complications after living kidney donation: A National study. Am J Transplant 16: 1848–1857, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiessen C, Jaji Z, Joyce M, Zimbrean P, Reese P, Gordon EJ, Kulkarni S: Opting out: A single-centre pilot study assessing the reasons for and the psychosocial impact of withdrawing from living kidney donor evaluation. J Med Ethics 43: 756–761, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hays R: Contraindications to living donation from an ILDA perspective. In: Living Donor Advocacy, New York, Springer, 2014, pp 205–219 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hildebrand L, Melchert TP, Anderson RC: Impression management during evaluation and psychological reactions post-donation of living kidney donors. Clin Transplant 28: 855–861, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young A, Karpinski M, Treleaven D, Waterman A, Parikh CR, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Yang RC, Garg AX: Differences in tolerance for health risk to the living donor among potential donors, recipients, and transplant professionals. Kidney Int 73: 1159–1166, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maple NH, Hadjianastassiou V, Jones R, Mamode N: Understanding risk in living donor nephrectomy. J Med Ethics 36: 142–147, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigue JR, Vishnevsky T, Fleishman A, Brann T, Evenson AR, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA: Patient-reported outcomes following living kidney donation: A single center experience. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 22: 160–168, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canadian Organ Replacement Register : CORR annual statistics: Organ donors, 2007–2016, Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canada, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 43.ANZDATA Registry : Monthly report on living kidney donation in Australia, Adelaide, Australia, Austrlaian and New Zealand Living Kidney Donation Registry, 2017 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.