Abstract

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are the first‐line treatment for patients with EGFR mutant non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, most patients become resistant to these drugs, so their disease progresses. Osimertinib, a third‐generation EGFR‐TKI that can inhibit the kinase even when the common resistance‐conferring Thr790Met (T790M) mutation is present, is a promising therapeutic option for patients whose disease has progressed after first‐line EGFR‐TKI treatment. AURA3 was a randomized (2:1), open‐label, phase III study comparing the efficacy of osimertinib (80 mg/d) with platinum‐based therapy plus pemetrexed (500 mg/m2) in 419 patients with advanced NSCLC with the EGFR T790M mutation in whom disease had progressed after first‐line EGFR‐TKI treatment. This subanalysis evaluated the safety and efficacy of osimertinib specifically in 63 Japanese patients enrolled in AURA3. The primary end‐point was progression‐free survival (PFS) based on investigator assessment. Improvement in PFS was clinically meaningful in the osimertinib group (n = 41) vs the platinum‐pemetrexed group (n = 22; hazard ratio 0.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.13‐0.56). The median PFS was 12.5 and 4.3 months in the osimertinib and platinum‐pemetrexed groups, respectively. Grade ≥3 adverse events determined to be related to treatment occurred in 5 patients (12.2%) treated with osimertinib and 12 patients (54.5%) treated with platinum‐pemetrexed. The safety and efficacy results in this subanalysis are consistent with the results of the overall AURA3 study, and support the use of osimertinib in Japanese patients with EGFR T790M mutation‐positive NSCLC whose disease has progressed following first‐line EGFR‐TKI treatment. (ClinicalTrials.gov trial registration no. NCT02151981.)

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor, Japanese, mutation, non‐small‐cell lung cancer, tyrosine kinase

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- CI

confidence interval

- CNS

central nervous system

- DCR

disease control rate

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- ILD

interstitial lung disease

- NSCLC

non‐small‐cell lung cancer

- ORR

objective response rate

- PFS

progression‐free survival

- SAE

serious adverse event

- T790M

EGFR Thr790Met mutation

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

1. INTRODUCTION

Epidermal growth factor receptor TKIs are established as the first line of treatment of patients with EGFR‐mutated NSCLC.1 However, resistance nearly always develops. Despite good response rates with first‐line EGFR‐TKIs, most patients experience disease progression within 8‐14 months of treatment.1, 2, 3 A point mutation in the EGFR gene leading to T790M is found in approximately 50%‐60% of EGFR‐TKI‐treated patients at the time of disease progression.4, 5, 6, 7 This mutation is believed to render the receptor refractory to inhibition by reversible first‐generation EGFR TKIs through effects on both steric hindrance8 and increased ATP affinity.9 Although afatinib, an irreversible second‐generation EGFR TKI, overcame T790M activity preclinically,10 it failed to overcome T790M‐mediated resistance in patients.11, 12

Two studies of Japanese individuals found that the prevalence of the EGFR T790M mutation was 50% and 64% in tumors with acquired resistance to EGFR‐TKIs.13, 14 A previous study showed a poor response to platinum‐based doublet chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in Japanese NSCLC patients with de novo and acquired EGFR T790M mutations, with overall response rates of 25.0% and 22.2% and median survival times of 29.1 and 15.3 months, respectively.15 After failure with first‐line EGFR‐TKI treatment in Japanese patients with EGFR mutation‐positive advanced NSCLC, responses to platinum‐based chemotherapy were poor, as shown by an ORR and median survival time of 25.4% and 28.9 months, respectively.16 A phase II study of NSCLC patients, including those with EGFR mutations, who experienced disease progression after erlotinib and/or gefitinib treatment also showed a poor response, with an ORR and median PFS of 8.2% and 4.4 months, respectively, after treatment with the irreversible ErbB family blocker, afatinib.12 In the same study, the best response in 2 patients with acquired EGFR T790M mutations was stable disease.

Osimertinib is an oral, irreversible, CNS‐penetrant EGFR‐TKI with high selectivity for mutated EGFR, including EGFR with the T790M mutation.17, 18 A phase I study of osimertinib found an overall ORR of 51% in patients who had progressed following prior treatment with EGFR‐TKI inhibitors. The response rate was 61% in evaluable patients with confirmed EGFR T790M, and 21% in those without detectable EGFR T790M.19 The safety and efficacy of osimertinib 80 mg once daily were studied in a phase II, single‐arm study in patients previously treated with an EGFR‐TKI. In the analysis of data from a phase II study in 199 patients, a complete objective response was obtained in 3% of patients, and partial responses in 67%, with manageable AEs.20

AURA3 is an international, randomized (2:1), open‐label, phase III clinical trial to compare the efficacy of osimertinib with that of platinum‐based therapy plus pemetrexed.21 The trial enrolled 419 EGFR T790M mutation‐positive patients with advanced NSCLC who had disease progression following first‐line EGFR‐TKI therapy. Approximately two‐thirds of the patients were Asian. Compared with platinum therapy plus pemetrexed, median PFS was significantly increased with osimertinib treatment (hazard ratio, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.23‐0.41; P < 0.001; 4.4 months vs. 10.1 months). Similarly, the ORR was significantly higher with osimertinib (71.1%) compared with platinum‐based therapy plus pemetrexed (31%).21 This current subgroup analysis, prespecified in the statistical analysis plan of the AURA3 study, was designed to investigate the efficacy and safety of osimertinib in the Japanese patients enrolled in AURA3.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Trial design

Patients were enrolled from 24 centers in Japan. The design of the study has been reported in detail elsewhere.21

In the overall cohort, patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either osimertinib or pemetrexed plus either carboplatin or cisplatin (platinum‐pemetrexed). Investigators chose either carboplatin or cisplatin for each patient before randomization. Patients were randomized centrally using an interactive voice/web response system. Sixty‐three (15%) of the 419 participants enrolled in the original AURA3 study were recruited in Japan and were included in the current analysis.

All patients provided written informed consent prior to screening. Patients were free to discontinue treatment or to withdraw consent to participate in the study at any time. The study adhered to the principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant local and international guidelines and was approved by ethics committees or institutional review boards at all participating institutions. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02151981).

2.2. Patients

Male and female patients aged ≥18 years (≥20 years in Japan) and who provided written informed consent were included. Specific inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) locally advanced or metastatic, histologically or cytologically documented NSCLC not amenable to surgery or radiotherapy; (ii) evidence of disease progression following first‐line EGFR‐TKI therapy; (iii) documented EGFR mutation and central confirmation of tumor EGFR T790M mutation from a tissue biopsy taken after disease progression following first‐line EGFR‐TKI treatment; (iv) WHO performance status of 0 or 1; (v) no more than 1 prior line of treatment for advanced NSCLC; and (vi) no prior neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in the 6 months preceding the first EGFR‐TKI treatment. Patients with stable asymptomatic CNS metastases (defined as not requiring corticosteroids for 4 weeks before study treatment) were eligible for inclusion.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) treatment with an approved EGFR‐TKI within 8 days of the first dose of study treatment; (ii) prior treatment with osimertinib or any T790M‐directed EGFR‐TKI; (iii) prior use of investigational agents or anticancer drugs within 14 days of randomization; and (iv) inadequate bone marrow reserve or organ function.

2.3. Interventions

This was an open‐label study. In the osimertinib group, patients received oral osimertinib at a dose of 80 mg once daily. In the platinum‐pemetrexed group, patients received i.v. pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 plus either carboplatin at an area under the plasma concentration‐time curve of 5, or cisplatin 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for up to 6 cycles. Optional maintenance pemetrexed treatment was permitted for patients whose disease had not progressed after 4 cycles of platinum‐pemetrexed.

Treatment continued until disease progression, the development of unacceptable AEs, or a request by either the patient or the physician to discontinue treatment. In accordance with a protocol amendment, patients assigned to platinum‐pemetrexed could be switched to osimertinib in the event of disease progression assessed by the investigator and confirmed by a blinded independent central review committee.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was PFS assessed by the investigator according to RECIST version 1.1. Analysis of PFS by a blinded independent central review committee was carried out as a sensitivity analysis. All patients had RECIST 1.1 assessments every 6 weeks until objective progression. Secondary outcome measures included overall survival, ORR, duration of response, DCR, tumor shrinkage, and safety and tolerability. Safety assessments included clinical chemistry, hematology and urinalysis, vital signs and physical examination, echocardiogram/multigated acquisition scan, and WHO performance status. Adverse events were classified using the NCI's CTCAE version 4.0.

2.5. Statistical analyses

A full description of the statistical analyses, including the sample size calculation, has been reported in detail elsewhere.21 The full analysis set included all randomized patients and was used for all efficacy and exploratory analyses. The safety analysis set comprised all patients who received at least 1 dose of randomized treatment. No statistical analyses were undertaken for safety data and they were presented as summary data. All calculations were carried out with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

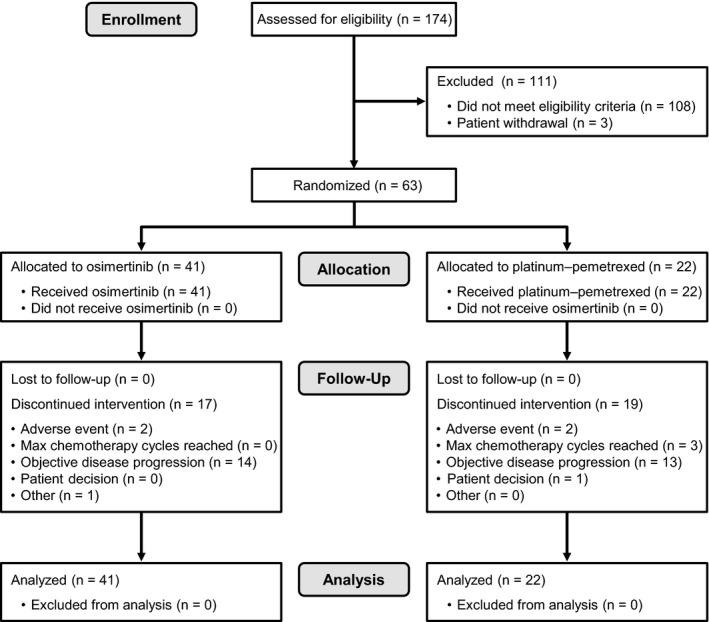

Patients were enrolled and randomized between August 2014 and September 2015. The tissue biopsy samples of 174 Japanese patients were screened by central testing for EGFR T790M mutations after progression, prior to study entry. Of the 111 patients excluded for not meeting eligibility criteria, EGFR T790M mutation was not confirmed in 97 patients. Sixty‐three Japanese patients were randomized and received treatment (osimertinib, n = 41; and platinum‐pemetrexed, n = 22). Fifteen out of 19 patients (78.9%) who discontinued randomized treatment in the platinum‐pemetrexed arm at the data cut‐off (15 April 2016) crossed over to the osimertinib arm. The patient disposition in the Japanese subgroup is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition in the Japanese subgroup of patients with EGFR T790M mutation‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer treated with osimertinib or platinum‐pemetrexed therapy. Patients in the platinum‐pemetrexed group were counted only if they discontinued all platinum‐pemetrexed treatment. If a patient discontinued platinum‐pemetrexed treatments at different times during the trial, they were counted under the last recorded reason for discontinuation of platinum‐pemetrexed. If a patient discontinued platinum‐pemetrexed treatments at the same time, the patient was counted under a single reason using the following order: adverse event, objective disease progression, severe protocol non‐compliance, lost to follow‐up, patient decision, maximum cycle of platinum‐pemetrexed reached, or other

Table 1 provides the characteristics of enrolled patients in the overall cohort and the Japanese subgroup. Patient characteristics in the Japanese subgroup were comparable with those in the overall study cohort. Baseline characteristics were generally balanced across treatment groups in the overall study cohort and in the Japanese subgroup. In the Japanese subgroup, 63.5% of patients were female (n = 40) and 65.1% were never‐smokers (n = 41). The percentage of patients with CNS metastases at baseline was 30.2% (n = 19) in the Japanese subgroup (29.3% in the osimertinib group and 31.8% in the platinum‐pemetrexed group; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics in the overall study cohort and Japanese subgroup of patients with EGFR T790M mutation‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer treated with osimertinib or platinum‐pemetrexed

| Characteristic | Osimertinib | Platinum‐pemetrexed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients21 (n = 279) | Japanese patients (n = 41) | All patients21 (n = 140) | Japanese patients (n = 22) | |

| Sex, % | ||||

| Male | 38.4 | 36.6 | 30.7 | 36.4 |

| Female | 61.6 | 63.4 | 69.3 | 63.6 |

| Age, years, median (range) | 62.0 (25‐85) | 69 (25‐85) | 63.0 (20‐90) | 67 (33‐90) |

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 31.9 | Japanese only | 32.1 | Japanese only |

| Asian | 65.2 | 65.7 | ||

| Othera | 2.8 | 2.1 | ||

| Smoking status, % | ||||

| Never | 67.7 | 68.3 | 67.1 | 59.1 |

| Current | 5.0 | 14.6 | 5.7 | 13.6 |

| Former | 27.2 | 17.1 | 27.1 | 27.3 |

| CNS metastasesb, % | 33.3 | 29.3 | 36.4 | 31.8 |

| EGFR mutationsc, % | ||||

| T790Md | 98.6 | 97.6 | 98.6 | 100.0 |

| Exdel19 | 68.5 | 56.1 | 62.1 | 72.7 |

| L858R | 29.7 | 39.0 | 32.1 | 27.3 |

| Othere | 2.2 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 0.0 |

| Number of previous anticancer regimens, % | ||||

| 1 | 96.4 | 95.1 | 95.7 | 100.0 |

| 2 | 3.2 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 0.4f | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Exdel19, exon 19 deletion; L858R, Leu858Arg mutation.

Including Black or African American and American Indian or Alaskan native.

Central nervous system (CNS) metastases determined programmatically from baseline date of CNS lesion site, medical history and/or surgery, and/or radiotherapy.

EGFR mutation identified by Cobas EGFR mutation test (by biopsy taken after confirmed progression on most recent treatment regimen).

Six patients without centrally confirmed Thr790Met (T790M) mutation‐positive status documented in the trial database/3 patients subsequently confirmed to be tumor T790M mutation‐positive. In the Japanese subgroup, 1 patient in the osimertinib group was reported as having missing results, but was T790M mutation‐positive (100% T790M positive, n = 63): the patient had a T790M positive result recorded under the patient's previous study code, which was missing from the database by error.

Includes G719X, S768I, and exon 20 insertion.

One patient had 3 previous anticancer regimens.

At the data cut‐off, the median duration of treatment was 9.95 months (range, 0.6‐17.5 months) for osimertinib and 5.03 months (range, 0.7‐14.0 months) for platinum‐pemetrexed. After disease progression, patients were treated with chemotherapy (platinum doublet, monotherapy), EGFR‐TKIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors, or radiation therapy.

3.2. Progression‐free survival and tumor responses

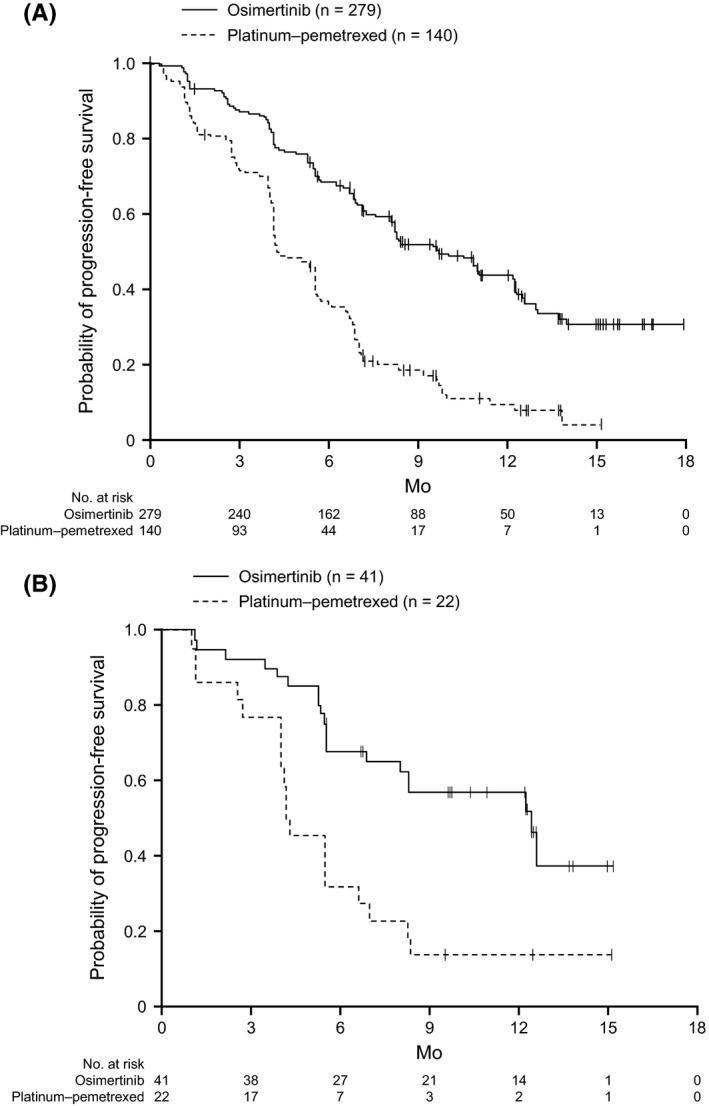

Figure 2 shows PFS in the global cohort21 and Japanese subgroup. PFS was longer in the osimertinib group than in the platinum‐pemetrexed group. In the Japanese subgroup, the hazard ratio was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.13‐0.56), and the median PFS was 12.5 months in the osimertinib group and 4.3 months in the platinum‐pemetrexed group. These results were consistent with those in the global cohort. Table 2 shows a comparison of best objective responses, the ORR, DCR, and duration of response in the 2 treatment groups. The mean reduction of tumor size in the target lesion after 6 weeks was 34.7% in the osimertinib group and 18.8% in the platinum‐pemetrexed group. All 41 patients in the osimertinib group showed a reduction of tumor size in the target lesion regardless of the best objective response (partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease). Among patients in the platinum‐pemetrexed group, most (19/22, 86.4%) showed a reduction of tumor size in the target lesion, except for 3 patients (3/22, 13.6%) who showed an increase of tumor size in the target lesion (1 patient with stable disease and 2 patients with progressive disease) (Figure S1). The findings for secondary outcomes were broadly similar between the Japanese patients and the overall cohort. Overall survival was not analyzed because the data were immature at the cut‐off.

Figure 2.

Progression‐free survival (PFS) using investigator assessment in all patients21 (A) and Japanese patients (B) enrolled with EGFR T790M mutation‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer treated with either osimertinib or platinum‐pemetrexed therapy. A, In all patients, the median PFS was 10.1 mo (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.3‐12.3) in the osimertinib group and 4.4 (95% CI, 4.2‐5.6) in the platinum‐pemetrexed group (hazard ratio, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.23‐0.41; P < 0.001). B, In the Japanese patients, the median PFS was 12.5 mo (95% CI, 6.9‐not calculated) in the osimertinib group and 4.3 (95% CI, 4.0‐6.7) in the platinum‐pemetrexed group (hazard ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.13‐0.56)

Table 2.

Tumor response in the Japanese subgroup of patients with EGFR T790M mutation‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer treated with osimertinib or platinum‐pemetrexed

| Osimertinib (n = 41) | Platinum‐pemetrexed (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|

| Best objective response, n (%) | ||

| Complete response | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Partial response | 29 (70.7) | 8 (36.4) |

| Non‐response (total) | 12 (29.3) | 14 (63.6) |

| Stable disease ≥6 wk | 10 (24.4) | 11 (50.0) |

| Progression | 2 (4.9) | 3 (13.6) |

| RECIST progression | 2 (4.9) | 2 (9.1) |

| Death | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) |

| Objective response rate (%)a | 70.7 | 36.4 |

| Disease control rate (%)b | 95.1 | 86.4 |

| Duration of response, median no. of months (95% CI)c | 11.1 (6.5‐NC) | 4.1 (1.5‐7.1) |

| Patients remaining in response, n (%) | ||

| >3 mo | 26 (89.7) | 5 (62.5) |

| >6 mo | 19 (65.5) | 2 (25.0) |

| >9 mo | 11 (37.9) | 1 (12.5) |

| >12 mo | 2 (6.9) | 1 (12.5) |

NC, not calculated.

Odds ratio, 4.23 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45‐13.23).

Odds ratio, 3.08 (95% CI, 0.47‐24.89).

From onset of response.

3.3. Safety

Adverse events occurred in all patients in both groups. Grade ≥3 AEs or SAEs were reported in a higher proportion of patients in the platinum‐pemetrexed group (Table 3). Adverse events that were determined as possibly related to treatment by investigators in the Japanese subgroup analysis (summarized in Table 4) occurred in 39 patients (95.1%) treated with osimertinib and 22 patients (100%) treated with platinum‐pemetrexed. Paronychia, diarrhea, and skin events including dry skin, pruritus, and dermatitis acneiform were observed in higher proportions in the osimertinib group than in the platinum‐pemetrexed group. Nausea, malaise, decreased appetite, anemia, constipation, decreased platelet count, decreased neutrophil count, decreased white blood cell count, increased alanine aminotransferase, increased aspartate aminotransferase, stomatitis, fatigue, and pyrexia were more frequent in the platinum‐pemetrexed group than in the osimertinib group.

Table 3.

Rates of adverse events (AEs) in the overall study cohort and Japanese subgroup of patients with EGFR T790M mutation‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer treated with osimertinib or platinum‐pemetrexed

| Osimertinib | Platinum‐pemetrexed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients21 (n = 279) | Japanese patients (n = 41) | All patients21 (n = 136) | Japanese patients (n = 22) | |

| AE, anya, n (%) | ||||

| Any AE | 273 (97.8) | 41 (100.0) | 135 (99.3) | 22 (100.0) |

| Any AE grade ≥3 | 63 (22.6) | 13 (31.7) | 64 (47.1) | 15 (68.2) |

| Any AE leading to death | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Any serious AE | 50 (17.9) | 5 (12.2) | 35 (25.7) | 6 (27.3) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation | 19 (6.8) | 3 (7.3) | 14 (10.3) | 2 (9.1) |

| AE, possibly causally related, n (%) | ||||

| Any AE | 231 (82.8) | 39 (95.1) | 121 (89.0) | 22 (100) |

| Any AE grade ≥3 | 16 (5.7) | 5 (12.2) | 46 (33.8) | 12 (54.5) |

| Any AE leading to death | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Any serious AE | 8 (2.9) | 1 (2.4) | 17 (12.5) | 5 (22.7) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation | 10 (3.6) | 3 (7.3) | 12 (8.8) | 2 (9.1) |

Safety analysis set (all patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug and for whom post‐dose data were available). Adverse events were assessed by the investigator, and include those with an onset date on or after the date of the first dose and up to and including 28 days following the date of the last dose of study medication.

Patients with multiple events in the same category were only counted once in that category. Those with events in more than 1 category were counted once in each category.

Table 4.

Possibly causally related adverse events (AEs) in the Japanese subgroup of patients with EGFR T790M mutation‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer treated with osimertinib or platinum‐pemetrexed

| Osimertinib (n = 41) | Platinum‐pemetrexed (n = 22) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Any grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| All AEs >15%, n (%) | ||||

| Any AE | 39 (95.1) | 5 (12.2) | 22 (100) | 12 (54.5) |

| Paronychia | 18 (43.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | 14 (34.1) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dry skin | 8 (19.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stomatitis | 7 (17.1) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (31.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pruritus | 7 (17.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dermatitis acneiform | 6 (14.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nausea | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (63.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Malaise | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (54.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Decreased appetite | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.4) | 11 (50.0) | 4 (18.2) |

| Anemia | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (45.5) | 4 (18.2) |

| Constipation | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (45.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Platelet count decreased | 4 (9.8) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (31.8) | 3 (13.6) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 3 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (31.8) | 4 (18.2) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 5 (12.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (22.7) | 2 (9.1) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 5 (12.2) | 2 (4.9) | 4 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fatigue | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 5 (12.2) | 2 (4.9) | 4 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pyrexia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Select adverse events <15%, n (%) | ||||

| Interstitial lung diseasea | 3 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| QT prolongation | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) |

Safety analysis set (all patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug and for whom post‐dose data were available). Adverse events were assessed by the investigator, and include those with an onset date on or after the date of the first dose and up to and including 28 days following discontinuation of randomized treatment or the day before first administration of cross‐over treatment if within 28 days. Some patients had more than 1 AE.

Grouped term: if a patient had multiple preferred term level events within a specific grouped term AE, then the maximum grade of CTCAE across those events was counted.

The CTCAE grade ≥3 AEs judged as possibly related to osimertinib included increased alanine aminotransferase, increased aspartate aminotransferase, diarrhea, and decreased appetite. Adverse events of CTCAE grade ≥3 were reported in 13 patients (31.7%) treated with osimertinib and in 15 patients (68.2%) treated with platinum‐pemetrexed. Grade ≥3 AEs that were determined as possibly related to treatment by investigators occurred in 5 patients (12.2%) treated with osimertinib and 12 patients (54.5%) treated with platinum‐pemetrexed. Adverse events causally related to treatment that led to treatment discontinuation occurred in 3 patients (7.3%) treated with osimertinib and 2 patients (9.1%) treated with platinum‐pemetrexed. In the osimertinib group, these were ILD‐like AEs (1 patient with grade 1 pneumonitis and 2 patients with grade 2 ILD). Grade 2 events of QT prolongation were reported in 1 patient (2.4%) treated with osimertinib and 1 patient (4.5%) treated with platinum‐pemetrexed (Table 4).

Serious AEs were less common in the osimertinib group than the platinum‐pemetrexed group (5 patients [12.2%] vs. 6 patients [27.3%], respectively). One Japanese patient, whose events were considered possibly related to study treatment by the investigator, developed interstitial pneumonitis almost 7 months after starting treatment, and treatment was discontinued. Nine days later, pneumothorax was reported but the patient subsequently recovered. In total, 4 (9.8%) patients in the osimertinib group and 5 (22.7%) patients in the platinum‐pemetrexed group died, including those who died during the crossover period or after the follow‐up period. All 9 deaths, including all 4 in the osimertinib group, were considered related to the disease under investigation. No fatal SAE was reported in the Japanese subgroup.

4. DISCUSSION

The objective of the current study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of osimertinib in the 63 Japanese patients enrolled in AURA3. This was a randomized, open‐label, phase III clinical trial of NSCLC patients with the EGFR T790M mutation whose disease progressed after first‐line EGFR‐TKI treatment.

Our findings in the Japanese subgroup are consistent with those for the overall study cohort.21 Clinically relevant improvements were observed in PFS and tumor responses in the osimertinib group compared with the platinum‐pemetrexed group of the Japanese subgroup (hazard ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.13‐0.56). The median PFS was 12.5 months in the osimertinib group and 4.3 months in the platinum‐pemetrexed group.

Our results were similar to a previous Japanese phase III study in patients with advanced EGFR‐mutated NSCLC who were naïve to any EGFR‐TKIs and were randomized to treatment with another EGFR‐TKI treatment, gefitinib, or chemotherapy, although the target patients were TKI‐pretreated EGFR T790M mutation‐positive in this AURA3 study,2 which reported a significantly longer PFS with gefitinib than chemotherapy (10.4 months vs. 5.5 months, respectively; hazard ratio for PFS with gefitinib, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.25‐0.51; P < 0.001). This indicated that the use of osimertinib in patients harboring the EGFR T790M mutation after disease progression by prior EGFR‐TKI therapy is supported even in the Japanese population. Notably, among 174 Japanese and 1036 overall patients screened, 63 (36.2%) and 413 (39.9%) patients, respectively, were enrolled in the study with T790M mutation‐positive status.21 Thus, the proportion of patients with documented EGFR T790M mutation between the Japanese and global cohorts was broadly similar.

Treatment options for NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations who experienced disease progression after EGFR‐TKI therapy are limited. The LUX‐Lung 1 and LUX‐Lung 4 trials evaluated the efficacy of afatinib in NSCLC patients after failure with erlotinib or gefitinib in a global study cohort and Japanese patients, respectively.11, 12 In these studies, only a small portion of the patients possessed EGFR T790M mutations. The PFS ranged between 3 and 4 months, ORR ranged between 7% and 8%, and no clinically significant response was found.

The IMPRESS trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of continuing gefitinib combined with chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone in patients with EGFR mutation‐positive advanced NSCLC with acquired resistance to first‐line gefitinib. The median PFS and ORR for the pemetrexed plus carboplatin/cisplatin regimen in the IMPRESS trial were 5.4 months (95% CI, 4.6‐5.5) and 34%, respectively.22 Thus, the median PFS and ORR in the AURA3 trial is considered to be broadly similar to the historical data. However, these comparisons should be interpreted with caution as there is no specific study of platinum doublet chemotherapy in patients with T790M mutation‐positive NSCLC who have progressed on prior EGFR‐TKI therapy, and the trials compared here are heterogeneous.

A retrospective analysis of 24 patients treated with EGFR‐TKI rechallenge in combination with bevacizumab showed a higher DCR (88%) and a slightly longer PFS (4.1 months) than have previously been published for similar patients treated with EGFR‐TKI rechallenge alone. Furthermore, both the DCR and PFS in this study were higher in EGFR T790M mutation‐negative patients compared with those in EGFR T790M mutation‐positive patients (DCR 88% vs. 86% [P = 1.00] and PFS 4.1 vs. 3.3 months [P = 0.048], respectively).23 Although the present study showed clinically meaningful improvement in PFS in the osimertinib group vs the platinum‐pemetrexed group, further study is warranted to determine whether combination treatment with anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor therapy would provide any additional benefit, particularly in EGFR T790M mutation‐positive patients.

In the current study, there were small numerical differences in AEs in the osimertinib group compared with the overall study cohort (22%).21 However, the safety profile of osimertinib in the Japanese patients was broadly similar to the overall cohort and no new safety signals were presently identified. Three Japanese patients in the osimertinib group experienced 3 ILD‐related AEs (CTCAE grades 1 and 2), and all 3 patients recovered. There was no increase in ILD severity in the Japanese subgroup compared with the overall study cohort.

This study has some limitations, including its open‐label nature.21 Given that this was a subgroup analysis, the number of patients is relatively small, meaning results should be interpreted with some caution.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that osimertinib is effective as a standard regimen in Japanese NSCLC patients carrying the EGFR T790M mutation with disease progression after EGFR‐TKI therapy. Osimertinib was relatively well tolerated, with low incidences of causally related AEs classified as CTCAE grade ≥3 or SAEs. The findings in this subgroup of Japanese patients were consistent with those observed in the overall study cohort.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Hiroaki Akamatsu, Nobuyuki Katakami, Terufumi Kato, and Fumio Imamura received honoraria and research funding from AstraZeneca. Isamu Okamoto and Masaharu Shinkai received research funding from AstraZeneca. Young Hak Kim received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical and research funding from AstraZeneca and Ono Pharmaceutical. Rachel A. Hodge and Hirohiko Uchida are employees of and hold stock in AstraZeneca. Toyoaki Hida received honoraria from AstraZeneca and research funding from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Taiho Pharma, Clovis Oncology, and Astellas. The study was designed under the responsibility of AstraZeneca. The study was funded by AstraZeneca; osimertinib was provided by AstraZeneca; AstraZeneca contributed to the study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by AstraZeneca. The authors thank Nicholas D. Smith, Helen Roberton, Sarah Williams, and Susan Cottrell (Edanz Medical Writing) for medical writing support, which was funded by AstraZeneca K.K. The authors also thank the following principal investigators from the participating institutions (all in Japan): Norihiko Ikeda from Tokyo Medical University Hospital, Tokyo; Hiroshi Sakai from Saitama Cancer Center, Saitama; Toshiaki Takahashi from Shizuoka Cancer Center, Shizuoka; Yasuhito Fujisaka from Osaka Medical College Hospital, Osaka; Hiroshige Yoshioka from Kurashiki Central Hospital, Okayama; Hiroshi Tanaka from Niigata Cancer Center Hospital, Niigata; Kazuo Kasahara from Kanazawa University Hospital, Ishikawa; Shinji Atagi from National Hospital Organisation Kinki Chuo Chest Medical Centre, Osaka; Koji Takeda from Osaka City General Hospital, Osaka; Miyako Satouchi from Hyogo Cancer Centre, Hyogo; Naoyuki Nogami from National Hospital Organization Shikoku Cancer Centre, Ehime; Ryo Koyama from Juntendo University Hospital, Tokyo; Tomonori Hirashima from Osaka Habikino Medical Center, Osaka; Kazuhiko Nakagawa from Kindai University Hospital, Osaka; Takashi Yokoi from Kansai Medical University Hospital, Osaka; Katsuyuki Kiura from Okayama University Hospital, Okayama; Makoto Maemondo from Miyagi Cancer Centre, Miyagi (currently Iwate Medical University, Iwate); and Shuji Murakami from Kanagawa Cancer Center, Kanagawa (currently National Cancer Centre Hospital, Tokyo).

Akamatsu H, Katakami N, Okamoto I, et al. Osimertinib in Japanese patients with EGFR T790M mutation‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: AURA3 trial. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:1930–1938. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13623

Funding informationAstraZeneca.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tan DS, Yom SS, Tsao MS, et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Consensus Statement on Optimizing Management of EGFR Mutation‐Positive Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer: Status in 2016. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:946‐963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non–small‐cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380‐2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non–small‐cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786‐792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR‐TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR‐mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2240‐2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias‐Santagata D, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oxnard GR, Arcila ME, Sima CS, et al. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR‐mutant lung cancer: distinct natural history of patients with tumors harboring the T790M mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1616‐1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sos ML, Rode HB, Heynck S, et al. Chemogenomic profiling provides insights into the limited activity of irreversible EGFR Inhibitors in tumor cells expressing the T790M EGFR resistance mutation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:868‐874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yun CH, Mengwasser KE, Toms AV, et al. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2070‐2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, et al. BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27:4702‐4711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, et al. Afatinib versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic non‐small cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib, or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (LUX‐Lung 1): a phase 2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:528‐538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Katakami N, Atagi S, Goto K, et al. LUXlung 4: a phase II trial of afatinib in patients with advanced nonsmall‐cell lung cancer who progressed during prior treatment with erlotinib, gefitinib, or both. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3335‐3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, et al. Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer and acquired resistance to gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5764‐5769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Uramoto H, Shimokawa H, Hanagiri T, Kuwano M, Ono M. Expression of selected gene for acquired drug resistance to EGFR‐TKI in lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2011;73:361‐365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yamane Y, Shiono A, Ishii Y, et al. Treatments and outcomes of advanced/recurrent non‐small cell lung cancer harboring the EGFR T790M mutation: a retrospective observational study of 141 patients in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:1135‐1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyauchi E, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Efficacy of chemotherapy after first‐line gefitinib therapy in EGFR mutation‐positive advanced non‐small cell lung cancer‐data from a randomized Phase III study comparing gefitinib with carboplatin plus paclitaxel (NEJ002). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45:670‐676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soejima K, Yasuda H, Hirano T. Osimertinib for EGFR T790M mutation‐positive non‐small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10:31‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skoulidis F, Papadimitrakopoulou VA. Targeting the gatekeeper: osimertinib in EGFR T790M mutation‐positive non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:618‐622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jänne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW, et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor‐resistant non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1689‐1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goss G, Tsai CM, Shepherd FA, et al. Osimertinib for pretreated EGFR Thr790Met‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (AURA2): a multicentre, open‐label, single‐arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1643‐1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mok TS, Wu YL, Ahn MJ, et al. Osimertinib or platinum‐pemetrexed in EGFR T790M‐positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:629‐640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Soria JC, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, et al. Gefitinib plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy in EGFR‐mutation‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer after progression on first‐line gefitinib (IMPRESS): a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:990‐998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Otsuka K, Hata A, Takeshita J, et al. EGFR‐TKI rechallenge with bevacizumab in EGFR‐mutant non‐small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;76:835‐841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials