Abstract

Background

The potential for a fibrin sealant patch to reduce the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) remains uncertain. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether a fibrin sealant patch is able to reduce POPF in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy.

Methods

In this multicentre trial, patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy were randomized to receive either a fibrin patch (patch group) or no patch (control group), and stratified by gland texture, pancreatic duct size and neoadjuvant treatment. The primary endpoint was POPF. Secondary endpoints included complications, drain‐related factors and duration of hospital stay. Risk factors for POPF were identified by logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 142 patients were enrolled. Forty‐five of 71 patients (63 per cent) in the patch group and 40 of 71 (56 per cent) in the control group developed biochemical leakage or POPF (P = 0·392). Fistulas were classified as grade B or C in 16 (23 per cent) and ten (14 per cent) patients respectively (P = 0·277). There were no differences in postoperative complications (54 patients in patch group and 50 in control group; P = 0·839), drain amylase concentration (P = 0·494), time until drain removal (mean(s.d.) 11·6(1·0) versus 13·3(1·3) days; P = 0·613), fistula closure (17·6(2·2) versus 16·5(2·1) days; P = 0·740) and duration of hospital stay (22·1(2·2) versus 18·2(0·9) days; P = 0·810) between the two groups. Multivariable logistic regression analysis confirmed that obesity (odds ratio (OR) 5·28, 95 per cent c.i. 1·20 to 23·18; P = 0·027), soft gland texture (OR 9·86, 3·41 to 28·54; P < 0·001) and a small duct (OR 5·50, 1·84 to 16·44; P = 0·002) were significant risk factors for POPF. A patch did not reduce the incidence of POPF in patients at higher risk.

Conclusion

The use of a fibrin sealant patch did not reduce the occurrence of POPF and complications after pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy. Registration number: 2013‐000639‐29 (EudraCT register).

Short abstract

Not effective in reducing complications

Introduction

The anastomosis between the pancreatic remnant and the intestinal tract is still the surgical Achilles heel after pancreatic head resection. Up to 27 per cent of patients develop a clinically relevant (grade B or C) postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), according to the recently updated International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition1, 2. Modification of several risk factors by adapting anastomotic techniques or interventions, such as use of octreotide and pancreatic duct drainage, has not had a significant effect on POPF rates in general3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12.

Some patients are at high risk of developing POPF regardless of the method of reconstruction and despite pharmacological depression of exocrine function. It is tempting to add additional sealing materials to cover the pancreatic anastomosis and thereby reduce the potential for overflow of pancreatic juice. Fibrin glue has been used extensively for this indication after both pancreatoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy, but has failed to demonstrate any benefit in most studies13. However, matrix‐bound adhesives have been investigated for their sealing properties in non‐haemostatic indications. Adhesives have shown beneficial results in sealing off air leakage of the lung, reducing the incidence of lymphatic leaks after urological and gynaecological interventions, and cerebrospinal fluid leaks after neurosurgery14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

As with fibrin glue, matrix‐bound sealants have previously shown no obvious advantage in preventing POPF in pancreatic surgery. However, most of the evidence has been obtained from distal pancreatectomy and few results have been reported for pancreatojejunostomy21, 22, 23, 24. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the ability of a fibrin‐coated collagen patch to reduce the risk of postoperative POPF in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy.

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and performed according to CONSORT guidelines25. It was designed as a multicentre, randomized, open, phase II, two‐arm trial, with six participating tertiary‐care centres in Austria specialized in pancreatic surgery, each of which had an annual frequency of more than 20 pancreatic resections. The first patient entered the study on 5 September 2013 and the final patient completed the study on 22 March 2015. Local ethics committee approval was received (1169/2013) and the study was registered in the European Clinical Trials register (EudraCT number 2013‐000639‐29).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included in the study were patients aged at least 18 years who were scheduled for partial pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy, able to comply with the protocol and attend follow‐up, and who signed written informed consent to participate in the study.

Patients with known allergies to any components of the patches tested were excluded from the study. Somatostatin or its analogues were not used routinely in this study, and patients receiving these compounds prophylactically were excluded given the lack of clear evidence supporting their use4.

Randomization

Patients were randomized on a 1 : 1 basis during surgery by the minimization method (preferred treatment probability 0·9), after resection but before anastomosis, to either fibrin‐coated collagen patch application (patch group) or no patch (control group)26. Randomization was done using a secure, internet‐based, randomization service (Randomizer®), provided by the Centre of Medical Statistics, Informatics and Intelligent Systems, Medical University of Vienna, Austria, to all participating sites. Randomization was stratified by pancreatic gland texture (soft or normal–firm), pancreatic duct diameter (up to 4 mm or larger than 4 mm) and neoadjuvant treatment received (yes or no).

Definitions of primary and secondary endpoints

POPF formation according to the ISGPS definition27, with adaptation according to the latest modification1 during analysis, was the primary endpoint of this study; it was assessed during the postoperative period until discharge and up to 42 days after surgery during the end‐of‐study visit. Secondary endpoints, assessed during the same interval, were postoperative surgery‐related complications graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification28, severity of POPF, amylase drainage fluid concentration, time until drain removal and time until fistula closure. Following the update of the fistula definition, asymptomatic grade A POPF was defined as biochemical leakage1. Duration of hospital stay was chosen as an exploratory endpoint.

Surgical procedure

Operative technique, patch placement and drainage were standardized between the participating centres. Briefly, partial pancreatoduodenectomy was performed with pylorus preservation, where appropriate. The pancreatic head and uncinate process were resected beyond the portal vein, and the resection was extended into the retroperitoneal, peripancreatic, pericaval and interaortocaval lymphatic–fatty tissue with regional lymphadenectomy. For reconstruction, one jejunal limb was moved upwards behind the transverse colon and a side‐to‐end pancreatojejunostomy was constructed as the first anastomosis, followed by biliary–enteric anastomosis and finally the gastrojejunostomy in an antecolic position. The pancreatojejunostomy was usually performed in a two‐layer, duct‐to‐mucosa, end‐to‐side technique, with interrupted sutures using monofilament threads according to the individual surgeon's preference.

Intervention

In patients randomized to the patch group, the pancreatojejunostomy was sealed with two 9·5 × 4·8‐cm patches of fibrin‐coated collagen (TachoSil®; Takeda Austria, Linz, Austria) that were placed on the anterior and posterior aspect of the anastomosis according to the manufacturer's instructions, thereby wrapping the reconstruction entirely with a 2‐cm rim on both the jejunal wall and pancreatic tissue. The pancreatojejunostomy was left bare in the control group.

Use and removal of drains

In both groups, two capillary action drains (WEB‐SIL® Easy Flow Drain; Websinger, Wolkersdorf, Austria) were placed closed to the pancreatojejunostomy from the left side of the abdominal wall. Another two drains were placed on the right side underneath the liver close to the hepaticojejunostomy. The drain fluid concentration of amylase and lipase was measured daily on both sides for each patient, and the maximum was used for comparison between groups. The policy for drain removal during the postoperative course was the same at all participating centres. Each drain was removed when the drain fluid amylase concentration had been less than three times the institutional upper normal serum level (100 units/l) for 2 consecutive days. In asymptomatic patients with persisting amylase‐rich drain fluid, the drains remained in place until the fluid volume was less than 30 ml per day and were then retracted stepwise.

Follow‐up

The end‐of‐study visit was scheduled between 21 and 42 days after surgery, usually in the outpatient clinic.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 142 patients, 71 in each group, was calculated based on a type I error α = 0·05, power (1– β) = 0·8, using a two‐sided χ2 test. It was assumed that 30 per cent of the patients undergoing partial pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy would develop a biochemical leak or POPF after surgery. Furthermore, a 70 per cent reduction in biochemical leakage/POPF was considered as a significant clinical improvement with this treatment.

The intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population comprised all randomized patients who provided signed informed consent. Analysis of the primary endpoint was based on the ITT population, with each patient analysed according to randomization. Patients who were not evaluable for the primary endpoint, those who underwent total pancreatectomy and patients with missing information regarding fistula were considered to have a POPF. These patients were excluded from the analyses of secondary endpoints. Primary and secondary endpoint analyses were not adjusted for stratification factors. However, a co‐variable‐adjusted effect of the fibrin sealant patch on the primary endpoint was also derived.

Categorical data are presented as numbers with percentages, and continuous data as mean(s.d.) or median (i.q.r.). The χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used for analysis of categorical data and Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. The mean daily content of drain amylase (total and pancreatic‐specific) and lipase was calculated over all predefined time points for each patient, and compared between the groups.

Time to event was calculated as the time from randomization to drain removal (time point at which all drains had been removed from both sides), fistula closure and hospital discharge. Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed and compared by means of the log rank test.

Prognostic baseline and surgery‐related factors for the occurrence of biochemical leakage/POPF were tested in a multivariable logistic regression model, with results expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Predictive risk factors were derived retrospectively from the present study cohort and patients were categorized into risk groups according to number of risk factors present.

All statistical tests were two‐tailed and P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was undertaken by the Department of Statistics, Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG) using SAS® version 9.3 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

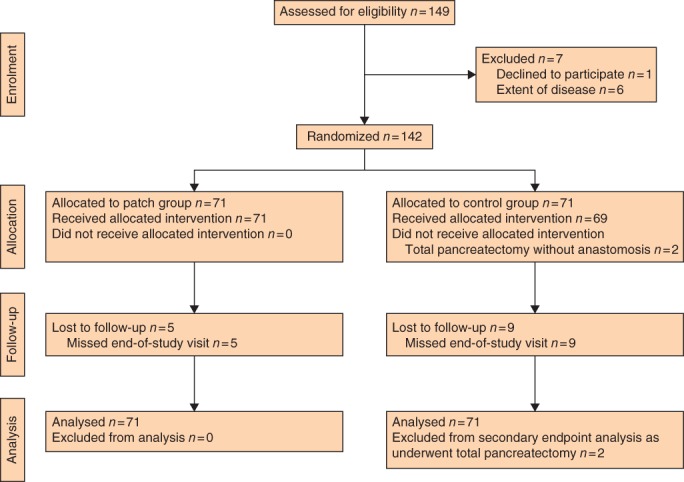

In total, 142 patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy were included in the study, 71 in each group (Fig. 1). Two patients (2·8 per cent) randomized to the control group underwent total pancreatoduodenectomy owing to positive resection margins on subsequent frozen sections from the pancreatic remnant. There were no differences in patient characteristics and risk factors for POPF between the two groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for the trial

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and risk factors for postoperative pancreatic fistula

| Patch group | Control group | All patients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 71) | (n = 71) | (n = 142) | |

| Age (years)* | 66·7(9·1) | 66·2(10·2) | 66·5(9·7) |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 34 : 37 | 33 : 38 | 67 : 75 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| ≥ 30 | 14 (20) | 8 (11) | 22 (15·5) |

| < 30 | 57 (80) | 60 (85) | 117 (82·4) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | 3 (2·1) |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |||

| Yes | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 6 (4·2) |

| No | 68 (96) | 68 (96) | 136 (95·8) |

| Pancreatic duct size (mm) | |||

| > 4 | 21 (30) | 24 (34) | 45 (31·7) |

| ≤ 4 | 50 (70) | 47 (66) | 97 (68·3) |

| Pancreatic gland texture | |||

| Soft | 42 (59) | 35 (49) | 77 (54·2) |

| Normal–firm | 29 (41) | 34 (48) | 63 (44·4) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 2 (1·4) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean(s.d.).

Risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula

After surgery, biochemical leakage or POPF occurred in 85 of 142 patients (59·9 per cent), 45 of 71 (63 (95 per cent c.i. 51 to 75) per cent) in the patch group and 40 of 71 (56 (44 to 68) per cent) in the control group (P = 0·392); the risk difference was 7·0 (95 per cent c.i. –9·0 to 23·1) and the risk ratio 1·13 (0·86 to 1·47). Although the leakage of pancreatic juice was clinically asymptomatic in the majority of patients, some developed clinically relevant grade B and C POPF, with no significant differences between the groups (P = 0·534) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Occurrence of biochemical leakage and postoperative pancreatic fistula

| Patch group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 70)* | (n = 69)† | |

| None | 26 (37) | 31 (45) |

| Biochemical leakage | 28 (40) | 28 (41) |

| POPF B | 13 (19) | 7 (10) |

| POPF C | 3 (4) | 3 (4) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

One patient had no fistula grading information.

Two patients underwent procedures other than pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy. POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula. P = 0·534 (Fisher's exact test).

Secondary outcomes

There was no significant difference in surgical complications between the two groups (Table 3). Overall, six of 142 patients (4·2 per cent), two (3 per cent) in the patch group and four (6 per cent) in the control group underwent reoperation (P = 0·518). Surgical revision was undertaken in three patients with resuturing of the pancreatojejunostomy, whereas the anastomosis was abandoned in two other patients, and one patient underwent reoperation on the first postoperative day for haemorrhage unrelated to pancreatic leakage. Five of 142 patients (3·5 per cent), one (1 per cent) in the patch group and four (6 per cent) in the control group died during the postoperative course. The underlying cause of death was postoperative haemorrhage in two patients, sepsis‐related multiple organ failure in two, and sudden pulmonary embolism on the first postoperative day in one patient. Comparison of all adverse events per patient and maximum grade (P = 0·439) as well as severe adverse events (P = 0·246) showed no significant differences between the two groups. None of the recorded severe adverse events raised any concern about the safety of use of fibrin sealant patches during surgery.

Table 3.

Postoperative complications according to Clavien–Dindo grade

| Patch group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 71) | (n = 70)* | |

| None | 17 (24) | 20 (29) |

| Grade I | 13 (18) | 12 (17) |

| Grade II | 21 (30) | 19 (27) |

| Grade III | 18 (25) | 14 (20) |

| Grade IV | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

| Grade V | 1 (1) | 3 (4) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Clavien–Dindo grade missing for one patient. P = 0·839 (Fisher's exact test).

Drain fluid, amylase levels, drain removal and duration of hospital stay

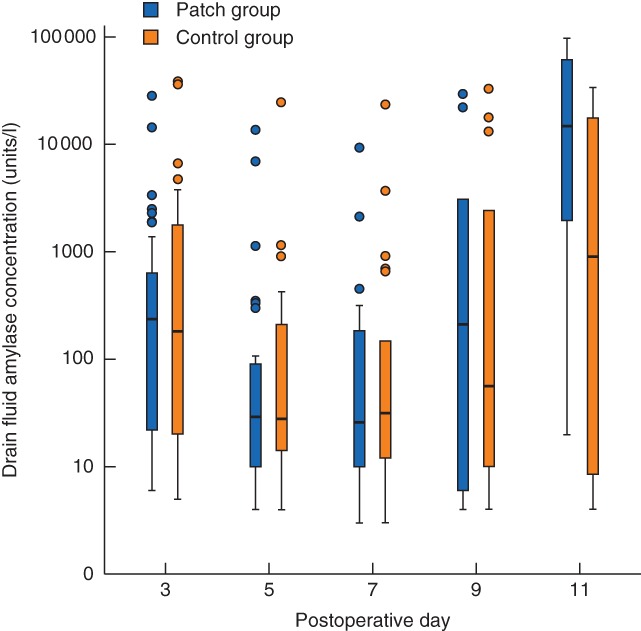

There were no significant differences between the groups in drain fluid concentrations of total amylase (median 110·5 and 90·5 units/l in patch and control groups respectively; P = 0·494) (Fig. 2), pancreas‐specific amylase (median 34·0 versus 38·5 units/l; P = 0·632) or lipase (median 267·3 versus 213·3 units/l; P = 0·613) during the postoperative observation period between the groups.

Figure 2.

Drain fluid concentration of total amylase after surgery. Median values (bold line), i.q.r. (box), and range (error bars) excluding outliers (circles) are shown

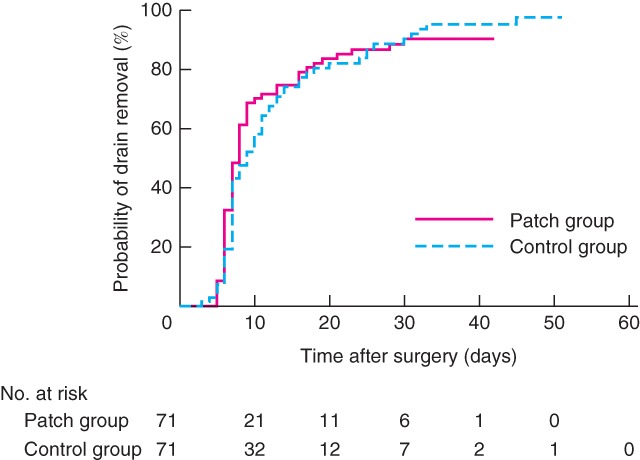

In time‐to‐event analyses, the mean(s.d.) time to removal of all drains was 11·6(1·0) days in the patch group and 13·3(1·3) days in the control group (P = 0·613, log rank test) (Fig. 3). Time until cessation of amylase‐rich fluid secretion from drainage sites (fistula closure) was comparable in the two groups (17·6(2·2) days in the patch group and 16·5(2·1) days in the control group; P = 0·740). The mean duration of hospital stay was 22·1(2·2) and 18·2(0·9) days respectively (P = 0·810).

Figure 3.

Mean time to drain removal after surgery. P = 0·613 (log rank test)

Risk model for postoperative pancreatic fistula

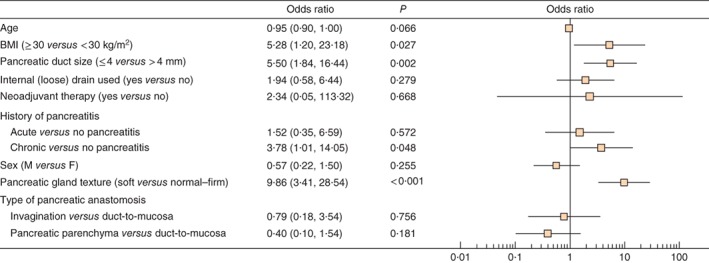

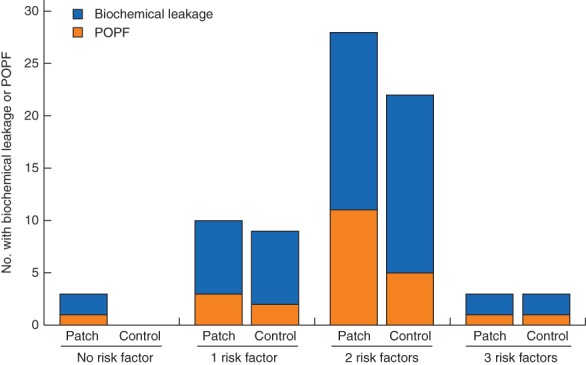

A multivariable logistic regression model identified obesity, pancreatic duct diameter of 4 mm or smaller and a soft texture of the pancreatic remnant as independent risk factors for biochemical leakage and POPF in the study cohort (Fig. 4). In patients with one or more risk factors present there was no significant difference in biochemical leakage/POPF rates between the patch and control groups (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Multivariable model of risk factors for biochemical leakage/postoperative pancreatic fistula. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Figure 5.

Incidence of biochemical leakage and postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) according to number of risk factors for fistula. P = 0·582 (Fisher's exact test)

Discussion

This multicentre randomized study could not prove that the use of fibrin‐coated collagen had any protective effect on the incidence and severity of POPF. Nor were there any significant differences in secondary endpoints, such as postoperative complications, time to drain removal and duration of hospital stay in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy. Subgroup analyses demonstrated no protective effect in patients with a higher risk of POPF.

Matrix‐bound sealants are composed of a carrier such as collagen or gelatin to stimulate endogenous coagulation, with or without additional active components (fibrinogen and thrombin). Although fibrin sealant patches were originally designed to improve haemostasis during surgery, there is an increasing number of publications about their tissue‐sealing properties for indications such as tightening anastomoses in gastrointestinal surgery, and sealing air leakage in pulmonary surgery, lymphatic leakage in urology and gynaecology, and cerebrospinal fluid leakage in neurosurgery29, 30, 31, 32. In the majority of previous studies in pancreatic surgery21, 22, 33, 34, sealant patches were used to cover the pancreatic stump after distal pancreatic resection.

Only two previous studies23, 24, including a total of 94 patients, have investigated the incidence of POPF after sealing pancreatojejunostomies with fibrin sealant patches. In a non‐randomized single‐centre study of 54 patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy23, half of the patients received a fibrin sealant patch layered on to the pancreatojejunostomy and the other half served as controls. The POPF rate was 7 per cent in the entire cohort, with one grade B and two grade A POPFs in the control group, and one grade A fistula in the patch group. Although the differences between groups were not significant, the authors suggested a possible advantage of fibrin sealant patches in the prevention of POPF. In a single‐centre observational study24 that included 40 patients with duct‐to‐mucosa pancreatojejunostomy covered by fibrin sealant patch, 13 per cent of patients developed grade A and 8 per cent grade B POPF. There was no postoperative pancreatic haemorrhage, and the duration of hospital stay was comparable between patients with or without pancreatic fistula. The authors concluded that sealing pancreatic anastomoses is safe and reliable for the prevention of POPF following pancreatoduodenectomy. These two studies were the only investigations with a clinical scenario and endpoints similar to those of the present trial, but involved a considerably smaller number of patients and were limited by a non‐randomized or single‐arm design. Taken the lack of randomized studies, the results of the present study provide important evidence about the performance of fibrin sealant patches applied to pancreatic anastomoses.

The popularity of sealant patches in pancreatic surgery is mainly related to the assumption that these products may reduce the overflow of pancreatic juice from the anastomosis during the first few days after surgery, thereby reducing biochemical leakage and its sequelae, such as inflammatory retention and late haemorrhage35. The present results do not support this hypothesis. Biochemical leakage and POPF occurred in more than half of patients, with no differences between the patch and control groups. Even in a high‐risk group of patients with a small pancreatic duct and soft gland texture, patches did not have a protective effect against pancreatic juice leaking from the anastomosis or related complications.

The lack of success of fibrin sealant patches placed on the pancreatojejunostomy may be explained by the finding that, under in vitro conditions, both liquid and carrier‐bound forms of fibrin were rapidly and grossly degraded by the enzymes in pancreatic fluid36. After surgery, the enzymatic activity of leaking pancreatic juice may decrease both the adhesive strength and sealing properties of fibrin sealant, paving the way for POPF regardless of whether a patch is used.

Furthermore, there is growing evidence that POPFs have a complex aetiology, with postoperative pancreatitis and pancreatic necrosis as contributory factors. In addition, impaired blood perfusion and disruption of the gland remnant by surgical trauma have an important negative impact on the healing of a pancreatic anastomosis37, 38, 39. Although some studies38, 40 have shown that ensuring an adequate blood supply to the pancreatic remnant is essential for uneventful anastomotic healing, there is currently no general agreement about any standardized assessment of pancreatic remnant blood perfusion and postoperative pancreatitis39. In the present study, the decision to recut the surface after initial pancreatic transection was based on the result of frozen‐section analysis and the individual surgeon's assessment of the remaining pancreatic tissue, but without objective evaluation. The contribution of impaired blood flow of the pancreatic remnant and postoperative pancreatitis to the occurrence of biochemical leakage/POPF cannot be ascertained from the present findings, and further research on this topic is needed.

The outcome measures of the present trial were adapted retrospectively according to the new definition of POPF1, 27, but the incidence of biochemical leakage was kept in the report in order to provide a complete picture of the tightening capacity of fibrin sealant patches. The proportion of patients with biochemical leakage was significantly higher here than reported previously, whereas the incidence of grade B and C POPF was not2, 10, 41. The authors are not able to provide a conclusive explanation for this as the participating centres have a high annual caseload of pancreatic resections, with pancreatojejunostomy performed according to general standards, with little variation. Biochemical leakage may be under‐reported to some extent in daily practice, because of the lack of repetitive drain fluid measurements, compared with focused reporting of this endpoint in prospective trials.

The policy to remove drains only when there is no evidence of biochemical leakage on 2 consecutive days may have contributed to prolonged drainage and a number of persistent biochemical leaks. The authors believe that adopting risk‐dependent, individual decisions for drain placement and removal may reduce the number of biochemical leaks and POPFs.

Acknowledgements

The ABCSG is an independent, interdisciplinary academic non‐profit research organization in Austria. The ABCSG received an unrestricted research grant from Takeda to augment study funding.

Disclosure: The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Preliminary results presented to the 12th Biennial Congress of the European–African Hepato‐Pancreato‐Biliary Association, Mainz, Germany, May 2017

References

- 1. Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M et al International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 2017; 161: 584–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pulvirenti A, Marchegiani G, Pea A, Allegrini V, Esposito A, Casetti L et al Clinical implications of the 2016 International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula on 775 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg 2017; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ecker BL, McMillan MT, Asbun HJ, Ball CG, Bassi C, Beane JD et al Characterization and optimal management of high‐risk pancreatic anastomoses during pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2017; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McMillan MT, Christein JD, Callery MP, Behrman SW, Drebin JA, Kent TS et al Prophylactic octreotide for pancreatoduodenectomy: more harm than good? HPB (Oxford) 2014; 16: 954–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shrikhande SV, Sivasanker M, Vollmer CM, Friess H, Besselink MG, Fingerhut A et al Pancreatic anastomosis after pancreatoduodenectomy: a position statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2017; 161: 1221–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kleespies A, Rentsch M, Seeliger H, Albertsmeier M, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. Blumgart anastomosis for pancreaticojejunostomy minimizes severe complications after pancreatic head resection. Br J Surg 2009; 96: 741–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Figueras J, Sabater L, Planellas P, Muñoz‐Forner E, Lopez‐Ben S, Falgueras L et al Randomized clinical trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy on the rate and severity of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2013; 100: 1597–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jang JY, Chang YR, Kim SW, Choi SH, Park SJ, Lee SE et al Randomized multicentre trial comparing external and internal pancreatic stenting during pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2016; 103: 668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CM Jr. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 216: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Senda Y, Shimizu Y, Natsume S, Ito S, Komori K, Abe T et al Randomized clinical trial of duct‐to‐mucosa versus invagination pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2017; 105: 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xiong JJ, Tan CL, Szatmary P, Huang W, Ke NW, Hu WM et al Meta‐analysis of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 1196–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Motoi F, Egawa S, Rikiyama T, Katayose Y, Unno M. Randomized clinical trial of external stent drainage of the pancreatic duct to reduce postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticojejunostomy. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 524–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheng Y, Ye M, Xiong X, Peng S, Wu HM, Cheng N et al Fibrin sealants for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreatic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (2)CD009621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anegg U, Lindenmann J, Matzi V, Smolle J, Maier A, Smolle‐Jüttner F. Efficiency of fleece‐bound sealing (TachoSil) of air leaks in lung surgery: a prospective randomised trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007; 31: 198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Belda‐Sanchís J, Serra‐Mitjans M, Iglesias Sentis M, Rami R. Surgical sealant for preventing air leaks after pulmonary resections in patients with lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; (1)CD003051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simonato A, Varca V, Esposito M, Venzano F, Carmignani G. The use of a surgical patch in the prevention of lymphoceles after extraperitoneal pelvic lymphadenectomy for prostate cancer: a randomized prospective pilot study. J Urol 2009; 182: 2285–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buda A, Ghelardi A, Fruscio R, Guelfi F, La Manna M, Dell'Orto F et al The contribution of a collagen–fibrin patch (Tachosil) to prevent the postoperative lymphatic complications after groin lymphadenectomy: a double institution observational study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016; 197: 156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gasparri ML, Ruscito I, Bolla D, Benedetti Panici P, Mueller MD, Papadia A. The efficacy of fibrin sealant patches in reducing the incidence of lymphatic morbidity after radical lymphadenectomy: a meta‐analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2017; 27: 1283–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Esposito F, Angileri FF, Kruse P, Cavallo LM, Solari D, Esposito V et al Fibrin sealants in dura sealing: a systematic literature review. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0151533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. George B, Matula C, Kihlström L, Ferrer E, Tetens V. Safety and efficacy of TachoSil (absorbable fibrin sealant patch) compared with current practice for the prevention of cerebrospinal fluid leaks in patients undergoing skull base surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Neurosurgery 2017; 80: 847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hüttner FJ, Mihaljevic AL, Hackert T, Ulrich A, Büchler MW, Diener MK. Effectiveness of Tachosil® in the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2016; 401: 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smits FJ, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Borel Rinkes IH, Molenaar IQ. Systematic review on the use of matrix‐bound sealants in pancreatic resection. HPB (Oxford) 2015; 17: 1033–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chirletti P, Caronna R, Fanello G, Schiratti M, Stagnitti F, Peparini N et al Pancreaticojejunostomy with application of fibrinogen/thrombin‐coated collagen patch (TachoSil) in Roux‐en‐Y reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13: 1396–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mita K, Ito H, Fukumoto M, Murabayashi R, Koizumi K, Hayashi T et al Pancreaticojejunostomy using a fibrin adhesive sealant (TachoComb) for the prevention of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2011; 58: 187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010; 340: c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics 1975; 31: 103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J et al; International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005; 138: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD et al The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five‐year experience. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sampanis D, Siori M. Surgical use of fibrin glue‐coated collagen patch for non‐hemostatic indications. Eur Surg 2016; 48: 262–268. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brustia R, Granger B, Scatton O. An update on topical haemostatic agents in liver surgery: systematic review and meta analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2016; 23: 609–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marano L, Di Martino N. Efficacy of human fibrinogen–thrombin patch (TachoSil) clinical application in upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery. J Invest Surg 2016; 29: 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Suárez‐Grau JM, Bernardos García C, Cepeda Franco C, Mendez García C, García Ruiz S, Docobo Durantez F et al Fibrinogen–thrombin collagen patch reinforcement of high‐risk colonic anastomoses in rats. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8: 627–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Park JS, Lee DH, Jang JY, Han Y, Yoon DS, Kim JK et al Use of TachoSil® patches to prevent pancreatic leaks after distal pancreatectomy: a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2016; 23: 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Montorsi M, Zerbi A, Bassi C, Capussotti L, Coppola R, Sacchi M. Efficacy of an absorbable fibrin sealant patch (TachoSil) after distal pancreatectomy: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg 2012; 256: 853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caronna R, Peparini N, Cosimo Russillo G, Antonio Rogano A, Dinatale G, Chirletti P. Pancreaticojejuno anastomosis after pancreaticoduodenectomy: brief pathophysiological considerations for a rational surgical choice. Int J Surg Oncol 2012; 2012: 636824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adelmeijer J, Porte RJ, Lisman T. In vitro effects of proteases in human pancreatic juice on stability of liquid and carrier‐bound fibrin sealants. Br J Surg 2013; 100: 1498–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lai ECH, Lau SHY, Lau WY. Measures to prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy: a comprehensive review. Arch Surg 2009; 144: 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Strasberg SM, McNevin MS. Results of a technique of pancreaticojejunostomy that optimizes blood supply to the pancreas. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 187: 591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Connor S. Defining post‐operative pancreatitis as a new pancreatic specific complication following pancreatic resection. HPB (Oxford) 2016; 18: 642–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Strasberg SM, Drebin JA, Mokadam NA, Green DW, Jones KL, Ehlers JP et al Prospective trial of a blood supply‐based technique of pancreaticojejunostomy: effect on anastomotic failure in the Whipple procedure. J Am Coll Surg 2002; 194: 746–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hackert T, Hinz U, Pausch T, Fesenbeck I, Strobel O, Schneider L et al Postoperative pancreatic fistula: we need to redefine grades B and C. Surgery 2016; 159: 872–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]