Abstract

Background

Stoma reversal is often considered a straightforward procedure with low short‐term complication rates. The aim of this study was to determine the rate of incisional hernia following stoma reversal and identify risk factors for its development.

Methods

This was an observational study of consecutive patients who underwent stoma reversal between 2009 and 2015 at a teaching hospital. Patients followed for at least 12 months were eligible. The primary outcome was the development of incisional hernia at the previous stoma site. Independent risk factors were assessed using multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Results

After a median follow‐up of 24 (range 12–89) months, 110 of 318 included patients (34·6 per cent) developed an incisional hernia at the previous stoma site. In 85 (77·3 per cent) the hernia was symptomatic, and 72 patients (65·5 per cent) underwent surgical correction. Higher BMI (odds ratio (OR) 1·12, 95 per cent c.i. 1·04 to 1·21), stoma prolapse (OR 3·27, 1·04 to 10·27), parastomal hernia (OR 5·08, 1·30 to 19·85) and hypertension (OR 2·52, 1·14 to 5·54) were identified as independent risk factors for the development of incisional hernia at the previous stoma site. In addition, the risk of incisional hernia was greater in patients with underlying malignant disease who had undergone a colostomy than in those who had had an ileostomy (OR 5·05, 2·28 to 11·23).

Conclusion

Incisional hernia of the previous stoma site was common and frequently required surgical correction. Higher BMI, reversal of colostomy in patients with an underlying malignancy, stoma prolapse, parastomal hernia and hypertension were identified as independent risk factors.

Introduction

Stoma reversal is often regarded as a straightforward and safe surgical procedure with low short‐term postoperative morbidity and mortality rates1. The stoma incision site, however, is at risk for the development of incisional hernia2. Earlier studies3, 4, 5 estimated the incidence of incisional hernia following stoma reversal as approximately 7 per cent. More recent studies6, 7, 8, designed specifically to investigate stoma‐site herniation, have reported a considerably higher incidence of 30–35 per cent. Incisional hernia following stoma closure may therefore be an underestimated clinical problem, causing abdominal pain, discomfort and impaired quality of life6. Medical consultation is often sought. Approximately 50 per cent of patients require surgical correction to relieve symptoms6. Hernia repair is often considered a high‐risk procedure due to co‐morbidities and intra‐abdominal adhesions from previous abdominal surgery9 10. The rate of incisional hernia at the stoma site seems to be much higher than rates of herniation following other abdominal incisions (10–15 per cent)11 12.

Further investigation of risk factors is warranted12. This could lead to new strategies for prevention of hernia in high‐risk patients. Prophylactic mesh placement at the previous stoma site during stoma closure may markedly decrease the risk of incisional hernia development6 13. It does, however, increase medical costs per procedure and may increase the risk of surgical‐site infection (SSI)14. The aim of this study was to quantify accurately the incidence of and identify risk factors for incisional hernia at the previous stoma site following reversal.

Methods

This was an observational study involving consecutive patients who underwent stoma reversal between January 2009 and December 2015 at a teaching hospital in the Netherlands. Patients were identified by operation code in the hospital's electronic medical system. Patients older than 18 years were analysed when they underwent reversal of an ileostomy or colostomy and had follow‐up longer than 12 months or an incisional herniation was observed.

Guidelines for oncological follow‐up in the Netherlands include outpatient visits at 6‐month intervals for the first 2–3 years and once a year until 5 years after resection. CT or abdominal ultrasound imaging is done 6 months after resection, and then on a yearly basis15. Medical records were retrieved to see whether incisional hernia was identified by physical examination, CT or ultrasonography during follow‐up. Patients whose clinical or radiological follow‐up (CT or ultrasound imaging) was less than 12 months after stoma reversal were contacted and asked whether the diagnosis of an incisional hernia had been made in another hospital or by their general practitioner. When the diagnosis was considered correct, two additional questions were asked, including when the hernia was diagnosed and whether or not the patient had undergone surgical correction. If incisional hernia had not been diagnosed at that time, the patient was invited to the outpatient clinic for physical examination of the previous stoma site. Any palpable defect was recorded. When it was clinically unclear, abdominal ultrasonography was performed in the supine position during a Valsalva manoeuvre.

All stoma reversals were performed under general anaesthesia. All patients received prophylactic antibiotics (cefmetazole 1 g and metronidazole 500 mg). An incision was made around the stoma, and the bowel was mobilized from surrounding tissues. In patients with a loop stoma, intestinal continuity was restored without the need for an additional laparotomy. When patients had an end stoma, laparotomy or laparoscopy was necessary to restore bowel continuity. Anastomosis was created by a double‐stapling technique for loop stomas and with a circular stapler for end stomas. The fascia defect was closed primarily with either continuous or interrupted absorbable sutures. The skin was closed using a purse‐string technique16. All procedures were performed or supervised by one of four experienced gastrointestinal surgeons.

Data collected from the patients' medical records included patient characteristics (age at stoma‐site closure, sex, BMI, ASA grade, smoking behaviour), co‐morbidities (diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension (defined as a systolic BP above 140 mmHg on more than three consecutive occasions), cardiovascular disease, previous abdominal surgery), surgical variables (operative technique, material and technique of sutures for fascia closure, preoperative haemoglobin, duration of hospital stay during stoma construction and reversal), stoma characteristics (colostomy or ileostomy, loop or end, indication for stoma), complications after reversal (reintervention, SSI, anastomotic leakage, postoperative ileus), and complications while the stoma was in situ (parastomal hernia, stoma prolapse, skin irritation, SSI, dehydration, stoma obstruction, high‐output stoma, pneumonia). Indication for the primary operation (benign or malignant), 30‐day mortality and in‐hospital mortality after stoma reversal were documented.

Endpoints

The primary outcome measure was whether or not an incisional hernia had developed at the previous stoma site. Incisional hernia was defined as a defect in the musculature and fascia detected by either physical examination, ultrasound examination or CT. Other outcomes included risk factors for stoma‐site incisional hernia development identified by multivariable analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). All variables are expressed as median (range) values. Categorical data are presented as number and percentage, and were compared with Fisher's exact test or the χ2 test as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using Mann–Whitney U and Student's t test as appropriate.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of incisional hernia development following stoma reversal. Variables with P < 0·100 in univariable analysis were entered in multivariable logistic regression analysis, keeping a 1 : 10 event per variable (EPV) ratio in mind. Several prespecified theoretically and biologically plausible interaction terms were added to the multivariable analysis to account for possible interaction. Statistical significance was set at P < 0·050 for all analyses.

Results

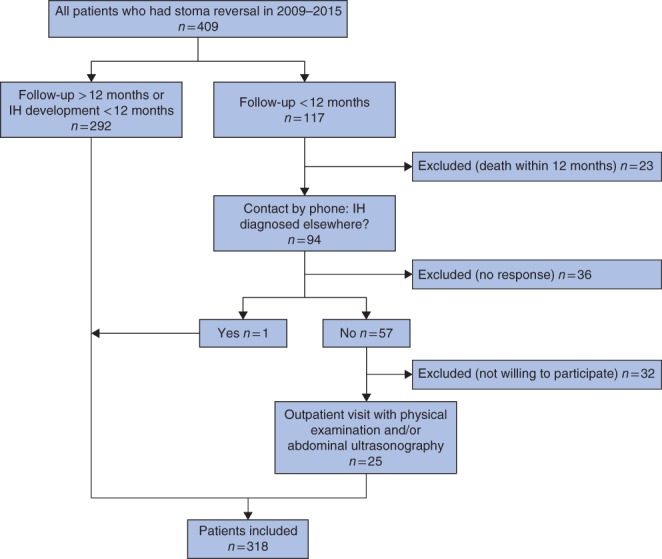

Some 409 patients underwent reversal of an ileostomy or colostomy between January 2009 and December 2015; 292 had been followed for more than 12 months or were diagnosed with a hernia before 12 months. The other 117 patients had limited follow‐up. Twenty‐five patients attended an outpatient clinic for further examination, so that eventually 318 patients (77·8 per cent) were analysed (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of patient selection. IH, incisional hernia

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the 318 patients, 143 (45·0 per cent) had a temporary ileostomy and 175 (55·0 per cent) had a temporary colostomy. Ninety‐five patients (29·9 per cent) had stoma‐related complications while the stoma was in situ.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total (n = 318) | Hernia (n = 110) | No hernia (n = 208) | P § | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 61·7 (53–72) | 61·7 (52–73) | 61·7 (54–71) | 0·992¶ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 170 : 148 | 52 : 58 | 118 : 90 | 0·108 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 26 (23–30) | 27·2 (23·5–32·5) | 25·5 (22–28) | < 0·001¶ |

| ASA fitness grade | 0·700 | |||

| I–II | 286 (89·9) | 98 (89·1) | 188 (90·4) | |

| III–IV | 32 (10·1) | 12 (10·9) | 20 (9·6) | |

| Indication for stoma construction | 0·001 | |||

| Protection of anastomosis | 194 (61·0) | 51 (46·4) | 143 (68·8) | |

| Anastomotic leak | 25 (7·9) | 10 (9·1) | 15 (7·2) | |

| Acute colonic obstruction | 52 (16·4) | 24 (21·8) | 28 (13·5) | |

| Other benign condition† | 47 (14·8) | 25 (22·7) | 22 (10·6) | |

| Underlying malignant disease | 191 (60·1) | 48 (43·6) | 143 (68·8) | < 0·001 |

| Current smoker | 66 (20·8) | 24 (21·8) | 42 (20·2) | 0·665 |

| Preoperative haemoglobin (mmol/l)* | 7·9 (7·2–8·5) | 8·1 (7·3–8·5) | 7·8 (7·1–8·4) | 0·140¶ |

| Co‐morbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 106 (33·3) | 47 (42·7) | 59 (28·4) | 0·012 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 41 (12·9) | 15 (13·6) | 26 (12·5) | 0·861 |

| COPD | 22 (6·9) | 6 (5·5) | 16 (7·7) | 0·643 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 69 (21·7) | 28 (25·5) | 41 (19·7) | 0·254 |

| Primary abdominal surgery | 0·796 | |||

| Open | 138 (43·4) | 49 (44·5) | 89 (42·8) | |

| Laparoscopic | 160 (50·3) | 53 (48·2) | 107 (51·4) | |

| n.a.‡ | 20 (6·3) | 8 (7·3) | 12 (5·8) | |

| Primary resection type | 0·131 | |||

| Left hemicolectomy | 22 (6·9) | 10 (9·1) | 12 (5·8) | |

| Right hemicolectomy | 13 (4·1) | 4 (3·6) | 9 (4·3) | |

| Subtotal colectomy | 19 (6·0) | 7 (6·4) | 12 (5·8) | |

| Sigmoidectomy | 101 (31·8) | 43 (39·1) | 58 (27·9) | |

| Low anterior resection | 143 (45·0) | 38 (34·5) | 105 (50·5) | |

| n.a.‡ | 20 (6·3) | 8 (7·3) | 12 (5·8) | |

| Adjuvant therapy | 49 (15·4) | 11 (10·0) | 38 (18·3) | 0·071 |

| Emergency surgery | 87 (27·4) | 39 (35·5) | 48 (23·1) | 0·024 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (i.q.r.).

Includes diverticulitis, slow‐transit colon and anal fistula.

Stoma construction was the primary surgery with no subsequent resection (anal fistula). COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n.a., not available.

χ2 or Fisher's exact test, except

Mann–Whitney U test.

Intraoperative data and complications are shown in Table 2. Median follow‐up was 24 (range 12–89) months. As most patients were followed up after resection of malignancy, radiological follow‐up exceeded 12 months in 230 patients (72·3 per cent). The remaining 88 patients with follow‐up of less than 12 months underwent physical examination to detect incisional hernia. Following stoma reversal, 110 patients developed an incisional hernia at the stoma incision site. The median time to hernia detection was 7 months. Eighty‐three (75·5 per cent) of the 110 hernias were detected within 12 months. Incisional herniation was diagnosed in 57 patients (51·8 per cent), by physical examination, in 12 (10·9 per cent) by CT and in eight (7·3 per cent) by ultrasound imaging. In 33 patients (30·0 per cent) the hernia was diagnosed by both physical examination and CT.

Table 2.

Intraoperative data and complications

| Total (n = 318) | Hernia (n = 110) | No hernia (n = 208) | P § | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of stoma | 0·001 | |||

| Ileostomy | 143 (45·0) | 36 (32·7) | 107 (51·4) | |

| Colostomy | 175 (55·0) | 74 (67·3) | 101 (48·6) | |

| Type of stoma | 1·000 | |||

| End | 282 (88·7) | 98 (89·1) | 184 (88·5) | |

| Loop | 36 (11·3) | 12 (10·9) | 24 (11·5) | |

| No. of patients with a stoma‐related complication | 100 (31·4) | 37 (33·6) | 63 (30·3) | 0·612 |

| Prolapse | 24 (7·5) | 13 (11·8) | 11 (5·3) | 0·039 |

| Parastomal hernia | 18 (5·7) | 10 (9·1) | 8 (3·8) | 0·067 |

| Dehydration | 19 (6·0) | 4 (3·6) | 15 (7·2) | 0·313 |

| Obstruction | 17 (5·3) | 5 (4·5) | 12 (5·8) | 0·785 |

| Necrosis | 5 (1·6) | 2 (1·8) | 3 (1·4) | 1·000 |

| High output | 23 (7·2) | 7 (6·4) | 16 (7·7) | 0·820 |

| Retraction | 4 (1·3) | 0 (0) | 4 (1·9) | 0·303 |

| Readmission for stoma‐related complication | 25 (7·9) | 10 (9·1) | 15 (7·2) | 0·662 |

| Time from stoma construction to closure (weeks)* | 16 (12–30) | 16 (12–31) | 16 (12–30) | 0·399¶ |

| Suture material for fascia closure‡ | 0·759 | |||

| Polydioxanone (PDS®) | 57 of 284 (20·1) | 21 of 100 (21·0) | 36 of 184 (19·6) | |

| Polyglactin (Vicryl®) | 227 of 284 (79·9) | 79 of 100 (79·0) | 148 of 184 (80·4) | |

| Suture technique | 0·461 | |||

| Intermittent | 217 of 283 (76·7) | 73 of 99 (73·7) | 144 of 184 (78·3) | |

| Continuous | 66 of 283 (23·3) | 26 of 99 (26·3) | 40 of 184 (21·7) | |

| Stoma closure technique | 0·856 | |||

| Local reversal | 257 (80·8) | 94 (85·5) | 163 (78·4) | |

| Including laparotomy | 45 (14·2) | 14 (12·7) | 31 (14·9) | |

| Including laparoscopy | 16 (5·0) | 2 (1·8) | 14 (6·7) | |

| Complications after reversal | ||||

| Surgical‐site infection | 29 (9·1) | 16 (14·5) | 13 (6·3) | 0·023 |

| Pneumonia | 17 (5·3) | 9 (8·2) | 8 (3·8) | 0·112 |

| Anastomotic leak | 3 (0·9) | 1 (0·9) | 2 (1·0) | 1·000 |

| Obstruction | 22 (6·9) | 9 (8·2) | 13 (6·3) | 0·643 |

| Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1·000 |

| Complications after reversal requiring reintervention | 30 (9·4) | 11 (10·0) | 19 (9·1) | 0·842 |

| Duration of follow‐up (months)*† | 27·5 (12–48) | 24 (12–48) | 28 (18–48) | 0·578§ |

| Radiological follow‐up > 12 months | 230 (72·3) | 78 (70·9) | 152 (73·1) | 0·388 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (i.q.r.).

The longest length of follow‐up was used for this variable; this could be the longest clinical (with physical examination) or radiological (CT or abdominal ultrasound imaging) follow‐up.

PDS® and Vicryl® both from Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey, USA.

χ2 or Fisher's exact test, except

Mann–Whitney U test.

The incisional hernia was symptomatic in 85 of 110 patients (77·3 per cent); 72 (65·5 per cent) required surgical correction. Patients with a symptomatic hernia who chose not to undergo surgical correction either had minor symptoms or were helped sufficiently with non‐surgical solutions such as abdominal wall support.

Several variables were identified as possible risk factors for the development of incisional hernia (P < 0·100 in univariable analysis). BMI, having a colostomy, stoma prolapse, parastomal hernia, SSI following stoma reversal, hypertension, undergoing adjuvant therapy, emergency stoma construction, having malignancy as underlying disease and indication for stoma construction were identified as possible risk factors and thus included in the multivariable logistic regression model. BMI, stoma prolapse, parastomal hernia, hypertension and colostomy reversal in patients with an underlying malignancy were identified as independent risk factors for the development of incisional hernia (Table 3). Type of stoma (colostomy versus ileostomy) was not a significant risk factor in patients with no underlying malignancy. Other interaction terms tested included BMI with hypertension, malignancy with wound infection, age with hypertension, and age with malignancy; none was statistically significant.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of risk factors for development of incisional hernia

| Odds ratio | P | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI | 1·12 (1·04, 1·21) | 0·004 |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0·457 | |

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 0·63 (0·18, 2·15) | |

| Indication for stoma | ||

| Protection of anastomosis | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Anastomotic leak | 0·64 (0·19, 2·17) | 0·477 |

| Acute colonic obstruction | 0·53 (0·05, 5·78) | 0·604 |

| Other benign condition* | 0·99 (0·13, 7·69) | 0·990 |

| Type of stoma | 0·584 | |

| Ileostomy | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Colostomy | 1·36 (0·46, 4·05) | |

| Surgical‐site infection | 0·307 | |

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 2·06 (0·52, 8·22) | |

| Prolapse | 0·042 | |

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 3·27 (1·04, 10·27) | |

| Parastomal hernia | 0·020 | |

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 5·08 (1·30, 19·85) | |

| Hypertension | 0·022 | |

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 2·52 (1·14, 5·54) | |

| Emergency surgery | 0·951 | |

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1·06 (0·15, 7·73) | |

| Malignancy | 0·779 | |

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1·18 (0·37, 3·71) | |

| Type of stoma in patients with malignant disease | 0·034 | |

| Ileostomy | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Colostomy | 5·05 (2·28, 11·23) |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Includes diverticulitis, slow‐transit colon and anal fistula.

Discussion

Incisional hernia at the previous stoma site occurred in approximately one‐third of patients after stoma reversal. This seems an appropriate reflection of the true patient population experiencing incisional herniation, as this was a consecutive cohort of patients who had a stoma for a variety of reasons. Many patients wished to undergo surgical correction of the hernia. Higher BMI, stoma prolapse, parastomal hernia, hypertension and colostomy reversal in patients with an underlying malignant disease were identified as independent risk factors for the development of incisional hernia.

The high rate of incisional hernia observed in this study is concordant with that observed in recent studies6, 7, 8 that focused specifically on this problem. Older studies reported markedly lower incisional hernia rates following stoma closure3, but tended to focus mainly on short‐term outcomes (complications, anastomotic leakage) following stoma reversal. Incisional hernia rate was a secondary outcome, and registration may thus have been less precise as follow‐up was short and incomplete6.

It is notable that rates of hernia following stoma reversal were substantially higher than rates seen with midline laparotomy wounds, of around 10 per cent11 12. A possible explanation could be that the fascial defect is larger in stoma wounds. In addition, the defect is oval‐shaped, and closure of these specific wounds may result in increased tension on the abdominal wall compared with that associated with laparotomy incisions. Tension may impair scarring of the fascia. Furthermore, stoma reversal is considered surgery in a possibly contaminated area. This might lead to higher rates of SSI, thought to be a risk factor for incisional hernia development17 18. The present study did not identify SSI as an independent risk factor; this might be explained by a low incidence of SSI owing to the use of purse‐string closure. This closure technique is known to decrease SSI markedly after stoma reversal19.

It has been suggested20 that a continuous suture technique with slowly absorbable monofilament suture material is preferred in order to prevent incisional hernias in laparotomy wounds. This preference, however, was based on the number of wound infections as primary outcome. Studies on preferred suturing materials, or whether a continuous or intermittent technique is preferred in order to prevent incisional hernia, are not available. It is known, however, that a small‐bites (5 mm) suture technique is more effective than a large‐bites (1 cm) technique in preventing incisional hernia21. Various suture techniques and materials were used in the present study, with no clear superiority for a particular technique (intermittent or continuous) or suture material. Unfortunately, it was not possible to retrieve from the surgical reports whether sutures were placed with small or large bites. The most effective closure technique for stoma wounds therefore remains unclear.

The surgical correction rate of diagnosed hernias was high in the present series compared with that in most previous reports6. This may be the result of longer follow‐up. In addition, a surgeon examined all patients, which could have lowered the threshold for reintervention. Another study14 with a similar follow‐up also found reintervention rates of around 70 per cent.

Several previous studies have looked at possible risk factors for incisional hernia following stoma reversal. High BMI and having a temporary colostomy were identified as significant risk factors in several of these studies6 8, 22 23. Parastomal hernia, stoma prolapse and hypertension have not been identified previously; most of these factors were not included in other studies. In addition, previous studies have had a considerably smaller sample size. Parastomal hernia or stoma prolapse increases the size of the existing fascial defect. This could further weaken the abdominal wall, making it more prone to incisional hernia development. The effects of hypertension on wound healing are less clear; possibly chronic microvascular changes secondary to hypertension could impair adequate tissue perfusion, thereby reducing proper wound healing and contributing to possible wound dehiscence22. It is likely that other factors identified in previous studies, such as diabetes mellitus and wound infection, are also independent risk factors for hernia development23. The low incidence of these factors in the present study might explain why they were not identified.

The most important limitation of this study is its retrospective design, which is prone to selection bias. Not all patients were followed for more than 12 months with imaging. In these patients, smaller asymptomatic incisional hernias may have been missed. This could have led to an underestimation of the true incisional hernia rate2 24.

Patients with risk factors have a higher risk of developing an incisional hernia. These patients would therefore benefit most from prophylactic measures. Stoma reversal in these high‐risk patients could even be regarded as a hernia repair rather than a simple fascia closure25. This might indicate the placement of a (prophylactic) mesh to prevent future herniation at the stoma incision site. Several retrospective studies6 13 of prophylactic mesh placement have shown promising results. RCTs, however, are lacking, but should be undertaken to determine whether mesh placement reduces the rate of incisional hernia at the stoma site without increasing SSIs.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding information

No funding

References

- 1. Chow A, Tilney HS, Paraskeva P, Jeyarajah S, Zacharakis E, Purkayastha S. The morbidity surrounding reversal of defunctioning ileostomies: a systematic review of 48 studies including 6107 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis 2009; 24: 711–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cingi A, Cakir T, Sever A, Aktan AO. Enterostomy site hernias: a clinical and computerized tomographic evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; 49: 1559–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tilney HS, Sains PS, Lovegrove RE, Reese GE, Heriot AG, Tekkis PP. Comparison of outcomes following ileostomy versus colostomy for defunctioning colorectal anastomoses. World J Surg 2007; 31: 1142–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bakx R, Busch OR, Bemelman WA, Veldink GJ, Slors JF, van Lanschot JJ. Morbidity of temporary loop ileostomies. Dig Surg 2004; 21: 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guenaga KF, Lustosa SA, Saad SS, Saconato H, Matos D. Ileostomy or colostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (1)CD004647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhangu A, Nepogodiev D, Futaba K. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of the incidence of incisional hernia at the site of stoma closure. World J Surg 2012; 36: 973–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhangu A, Fletcher L, Kingdon S, Smith E, Nepogodiev D, Janjua U. A clinical and radiological assessment of incisional hernias following closure of temporary stomas. Surgeon 2012; 10: 321−325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schreinemacher MH, Vijgen GH, Dagnelie PC, Bloemen JG, Huizinga BF, Bouvy ND. Incisional hernias in temporary stoma wounds: a cohort study. Arch Surg 2011; 146: 94−99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamel MB, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Daley J. Surgical outcomes for patients aged 80 and older: morbidity and mortality from major noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53:424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGugan E, Burton H, Nixon SJ, Thompson AM. Deaths following hernia surgery: room for improvement. J R Coll Surg Edinb 2000; 45: 183–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuhry E, Schwenk WF, Gaupset R, Romild U, Bonjer HJ. Long‐term results of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (2)CD003432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kingsnorth A, LeBlanc K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet 2003; 362: 1561−1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maggiori L, Moszkowicz D, Zappa M, Mongin C, Panis Y. Bioprosthetic mesh reinforcement during temporary stoma closure decreases the rate of incisional hernia: a blinded, case‐matched study in 94 patients with rectal cancer. Surgery 2015; 158: 1651−1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Barneveld KW, Vogels RR, Beets GL, Breukink SO, Greve JW, Bouvy ND et al Prophylactic intraperitoneal mesh placement to prevent incisional hernia after stoma reversal: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc 2014; 28: 1522−1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland . [National Working Group on Gastrointestinal Cancers. Guideline on Colonic Cancer 2.0] http://www.oncoline.nl/coloncarcinoom [accessed 22 October 2017].

- 16. Wada Y, Miyoshi N, Ohue M, Noura S, Fujino S, Sugimura K et al Comparison of surgical techniques for stoma closure: a retrospective study of purse‐string skin closure versus conventional skin closure following ileostomy and colostomy reversal. Mol Clin Oncol 2015; 3: 619−622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murray BW, Cipher DJ, Pham T, Anthony T. The impact of surgical site infection on the development of incisional hernia and small bowel obstruction in colorectal surgery. Am J Surg 2011; 202: 558−560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walming S, Angenete E, Block M, Bock D, Gessler B, Haglind E. Retrospective review of risk factors for surgical wound dehiscence and incisional hernia. BMC Surg 2017; 17: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Camacho‐Mauries D, Rodriguez‐Díaz JL, Salgado‐Nesme N, González QH, Vergara‐Fernández O. Randomized clinical trial of intestinal ostomy takedown comparing pursestring wound closure vs conventional closure to eliminate the risk of wound infection. Dis Colon Rectum 2013; 56: 205−211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heger P, Pianka F, Diener MK, Mihaljevic AL. [Current standards of abdominal wall closure techniques: conventional suture techniques.] Chirurg 2016; 87: 737−743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deerenberg EB, Harlaar J, Steyerberg EW, Lont HE, van Doorn HC, Heisterkamp J et al Small bites versus large bites for closure of abdominal midline incisions (STITCH): a double‐blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 1254−1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Van Ramshorst GH, Nieuwenhuizen J, Hop WC. Abdominal wound dehiscence in adults: development and validation of a risk model. World J Surg 2010; 34: 20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharp SP, Francis JK, Valerian BT, Canete JJ, Chismark AD, Lee EC. Incidence of ostomy site incisional hernias after stoma closure. Am Surg 2015; 81: 1244−1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bhangu A, Fletcher L, Kingdon S, Smith E, Nepogodiev D, Janjua U. A clinical and radiological assessment of incisional hernias following closure of temporary stomas. Surgeon 2012; 10: 321−325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cingi A, Solmaz A, Attaallah W, Aslan A, Aktan AO. Enterostomy closure site hernias: a clinical and ultrasonographic evaluation. Hernia 2008; 12: 401−405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]