Abstract

Background

Bariatric surgery is an accepted treatment option for severe obesity. Previous analysis of the independently collected Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data for outcomes after bariatric surgery demonstrated a 30‐day postoperative mortality rate of 0·3 per cent in the English National Health Service (NHS). However, there have been no published mortality data for bariatric procedures performed since 2008. This study aimed to assess mortality related to bariatric surgery in England from 2009.

Methods

HES data were used to identify all patients who had primary bariatric surgery from 2009 to 2016. Clinical codes were used selectively to identify all primary bariatric procedures but exclude revision or conversion procedures and operations for malignant or other benign disease. The primary outcome measures were HES in‐hospital and Office for National Statistics (ONS) 30‐day mortality after discharge.

Results

A total of 41 241 primary bariatric procedures were carried out in the NHS between 2009 and 2016, with 29 in‐hospital deaths (0·07 per cent). The 30‐day mortality rate after discharge was 0·08 per cent (32 of 41 241). Both the in‐hospital and 30‐day mortality rates after discharge demonstrated a downward trend over the study period.

Conclusion

Overall in‐hospital and 30‐day mortality rates remain very low after primary bariatric surgery. An increased uptake of bariatric surgery within the English NHS has been safe.

Introduction

In the UK, one in four adults and approximately one in five children are now obese, with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more1. For patients with severe and complex obesity (BMI at least 40 kg/m2 or 30 kg/m2 or above with obesity‐related disease), bariatric surgery has been shown to be significantly better than intensive lifestyle intervention at reducing weight and improving obesity‐related disease2 3. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends bariatric surgery as a treatment option for patients unable to lose weight by other means4. Although at least 5 per cent of the adult population in England exceeds the BMI thresholds for bariatric surgery, the uptake of National Health Service (NHS)‐funded surgery is much lower than in equivalent European countries5, 6, 7. The perceived risks of surgery may be one of the factors contributing to this.

Previous Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) analysis of the outcomes following bariatric surgery in England demonstrated a 30‐day postoperative mortality rate of 0·3 per cent for patients operated on between 2000 and 20088. HES data are an independently collected, national data resource, containing diagnostic, procedural and in‐hospital outcome data for all admissions, outpatient and emergency department attendances in NHS trusts in England9. It is the only data source that facilitates mortality analysis throughout the English NHS as a whole. The Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) (now NHS Digital) publishes procedure rates for bariatric surgery based on a selection of HES procedure codes in the absence of specific codes for most types of bariatric surgery10. The lack of specific bariatric procedure codes raises the possibility that the selection used for previous analysis may not have captured all primary bariatric procedures, and may have included some non‐bariatric procedures, with inaccurate outcome reporting. No mortality data related to these procedures have been published since 2008, despite an increase in rates of surgery. This study aimed to assess mortality rates after bariatric surgery using an updated set of HES codes that reflect current bariatric surgical practice in the English NHS.

Methods

Data sources

Data on 30‐day mortality after discharge, annual procedural counts (total and operation subtypes) and in‐hospital mortality rates via an existing linkage between the HES database and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) births, marriages and deaths register were extracted11. Patients are assigned a single primary diagnostic code taken from the ICD‐10. Procedural codes for interventions are assigned from the relevant OPCS version. Patient demographics were not extracted from the HES database. HES does not include BMI, and no data were extracted regarding co‐morbidities as HES reporting of them may not be accurate.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All NHS patients in England who underwent a primary, elective bariatric procedure between April 2009 and March 2016 were included. HES data include private patients treated at NHS hospitals and NHS patients treated at private hospitals; however, private patients were excluded from the present study. Secondary procedures were filtered using two mechanisms. The choice of OPCS codes eliminated secondary procedures with the description ‘Revision’ or ‘Conversion’. A second filter eliminated any procedure performed 1–30 days after a previous procedure. Secondary procedures involving conversion of a previous primary procedure to a new procedure (such as conversion of a gastric band to gastric bypass) were not included. Surgery involving revision of the anatomy of a primary bariatric procedure owing to therapeutic failure or early/late complications of surgery was also excluded.

Patients were identified from the HES data set using a combination of the principal reason for admission (ICD‐10 diagnostic code E66 – Obesity) and the procedures used for treatment (OPCS code). A procedure was assumed to have been elective when the primary diagnostic was E66. The list of OPCS codes selected was finalized from a list of 80 codes prevalent in the existing literature and publications from the HSCIC6 8, 12 13. Each code, code combinations and associated procedure descriptors were analysed individually, and cross‐referenced with the descriptions of bariatric procedures listed in the National Bariatric Registry (NBSR) reports6 12. Two bariatric surgeons chose a list of codes as being appropriate to describe bariatric surgery procedures that form the basis for case ascertainment of data submitted to the NBSR for the annual outcome reporting. Codes that could potentially lead to incorrect inclusion of patients undergoing gastric surgery for non‐bariatric indications (such as malignancy/benign disease) were excluded. Codes and code combinations with a low incidence, and describing a primary bariatric procedure otherwise described by a more populous code, were excluded. Finally, codes listed as ‘other specified procedure’, ‘non‐specific procedure’ and adjuncts to primary bariatric procedures were also excluded.

The final list of 15 OPCS codes used to identify bariatric procedures, categorized by operation type, compared with the HSCIC codes used for previous analysis and currently used by NHS Digital, is shown in Table 1. The four operation types were: gastric bypass (any bypass including Roux‐en‐Y), implant/temporary (gastric band, balloon, bubble), sleeve gastrectomy (including this operation plus duodenal switch) and duodenal switch alone.

Table 1.

OPCS codes utilized and excluded by the present study relative to the Health and Social Care Information Centre/NHS Digital codes used in previous outcome analysis

| Bariatric procedure | Utilized codes* | Excluded codes* |

|---|---|---|

| Bypass | G281, G301, G302, G304, G312, G321, G331 | G288, G289, G310, G311, G313, G314, G315, G316, G318, G319, G320, G322, G323, G324, G325, G328, G329, G330, G332, G333, G335, G336, G338, G339 |

| Sleeve gastrectomy | G282, G283, G284, G285 | |

| Implant/temporary | G303, G481, G485 | G308, G309 |

| Duodenal switch | G716 |

Codes and their full descriptors are shown in Table S1 (supporting information).

Outcome measures

The main outcome measures were in‐hospital mortality and 30‐day mortality after discharge. For the purposes of the HES data set, in‐hospital mortality is defined as a death occurring within the primary admission and before discharge. However, any death occurring after discharge, even when associated with a postoperative complication, is not captured by this measure.

ONS 30‐day postdischarge mortality is defined as any death occurring within 30 days of discharge from the primary admission, and captures readmissions and subsequent postoperative deaths within 30 days.

Statistical analysis

Counts of operations and mortality for each financial year from 2009–2010 to 2015–2016 were extracted from the HES database. Owing to NHS data governance reporting guidelines, exceedingly low mortality figures for a given year (fewer than 5) are not published, to avoid potential patient identification. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS® version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). The χ2 test was used to evaluate categorical variables. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Procedural analysis: HES data set

Between 2009 and 2016, HES data indicated 41 241 primary bariatric procedures, a mean of 5892 procedures per year. In comparison, procedural counts using the code choice currently used by the HSCIC and in previous HES analysis8 (Table 1) identified 45 416 procedures over the same period. Operation subtype‐specific procedural counts are shown, indicating increased uptake of sleeve gastrectomy and a decreasing rate of gastric banding (Table 2).

Table 2.

Annual and total procedure‐specific case counts over the study period

| Year | Procedure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bypass | Sleeve gastrectomy | Implant/temporary | Duodenal switch | |

| 2009–2010 | 3149 | 555 | 1649 | 10 |

| 2010–2011 | 3752 | 900 | 1544 | 15 |

| 2011–2012 | 3739 | 1410 | 1540 | 12 |

| 2012–2013 | 3672 | 1627 | 1110 | 8 |

| 2013–2014 | 3542 | 1544 | 704 | 18 |

| 2014–2015 | 3252 | 1764 | 524 | 17 |

| 2015–2016 | 2895 | 1777 | 494 | 18 |

| Total | 24 001 | 9577 | 7565 | 98 |

Mortality analysis

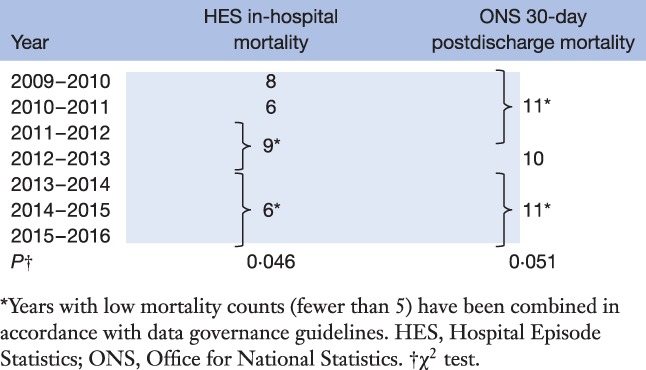

Table 3 shows the annual HES in‐hospital and ONS 30‐day postdischarge mortality rates, both indicating a trend for decreasing mortality. In‐hospital mortality fell from eight deaths in 2009–2010 to six in 2013–2016 (P = 0·046).

Table 3.

Annual in‐hospital (Hospital Episode Statistics) and 30‐day postdischarge (Office for National Statistics) deaths from primary bariatric surgery over the study period

The cumulative HES in‐hospital mortality rate was 0·07 per cent (29 of 41 241) and the ONS 30‐day postdischarge mortality rate was 0·08 per cent (32 of 41 241) (Table 4). In‐hospital and 30‐day mortality rates after discharge using codes employed in the previous mortality analysis8 (Table 1) are shown for comparison. There were no statistically significant differences in in‐hospital or 30‐day postdischarge mortality rates between the two sets of code choices (Table 4). Owing to the low number of total deaths, it was not possible to split mortality rates by procedure.

Table 4.

Comparison of cumulative in‐hospital and 30‐day mortality rates after discharge determined using codes employed in the present study and codes used in previous mortality analysis

| Cumulative mortality measure | ||

|---|---|---|

| In‐hospital mortality (%) | 30‐day postdischarge mortality (%) | |

| Codes used in present study (n = 15) | 0·07 | 0·08 |

| Codes used in previous analysis (n = 37) | 0·07 | 0·06 |

| P * | 0·824 | 0·190 |

χ2 test.

Discussion

Over the 7‐year study period, in‐hospital and 30‐day deaths from primary bariatric procedures in the NHS have remained low. The static in‐hospital and 30‐day mortality rates after discharge are encouraging, particularly given the reduction in temporary/implant procedures such as gastric banding, and the increased use of a more major intervention – sleeve gastrectomy14. Low mortality was independent of the choice of code used to identify bariatric procedures, with no significant difference between the mortality rates identified using a refined set of 15 codes in the present study and the 37 codes used currently by the HSCIC8 13. There was a statistically significant trend for decreased in‐hospital mortality over the period of analysis, although, owing to the overall low number of deaths, caution needs to be exercised in interpreting this as implying progressive improvement.

The in‐hospital mortality rate of 0·07 per cent and 30‐day mortality rate of 0·08 per cent are similar to those reported by the UK NBSR. Between 2009 and 2016, the NBSR reported a UK‐wide in‐hospital mortality rate of 0·08 per cent (31 of 39 745) in two comprehensive registry reports and elsewhere6 12, 15. Although HES data presented here are limited to mortality in England, the similarity between the present results and mortality data reported by the NBSR supports the accuracy of reporting, and suggests that HES data are representative of mortality across the UK.

Mortality in the present study is similar to that in other reports. Analysis of postoperative outcomes between 2005 and 2009 from ten centres (6118 patients) in the USA showed a mortality rate of 0·3 per cent within 30 days of surgery16. The Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative study17 of 15 275 patients reported a 30‐day mortality rate of 0·14 per cent after gastric bypass. A more recent meta‐analysis18 of 164 studies from 2003 to 2012 reported a 30‐day mortality rate of 0·08 per cent in RCTs and 0·22 per cent in observational studies. Bariatric surgery is thus as safe, or safer, than many other common elective procedures19 20.

In an earlier analysis of HES 30‐day mortality figures8, a mortality rate of 0·30 per cent was found following bariatric procedures conducted between 2000 and 2008, when 36 per cent of procedures were open operations. The present results showed fewer in‐hospital and 30‐day postdischarge deaths, despite a substantial increase in the annual number of primary bariatric procedures conducted since 2008. Although small in absolute terms, this difference may reflect improved techniques and the increased use of laparoscopic procedures, known to have better outcomes than those for open surgery8 21. Although the present study did not assess the proportion done openly, laparoscopy is now standard in bariatric surgery, accounting for over 95 per cent of primary procedures recorded in the NBSR in 2011–20136. Mortality rates for open versus laparoscopic approaches have not been reported from the NBSR.

The present study used 15 codes to identify and subsequently group the cohort into four types of bariatric procedure. In the earlier HES analysis8, 37 codes were used to define the three predominant bariatric procedures of gastric bypass, gastrectomy and gastric banding. The discrepancy in the number of codes included is due to the exclusion of 26 codes, and the subsequent inclusion of four additional codes (G284, G481, G485 and G716), through the methodology of code selection used in the present study, as indicated in Table 1. As the descriptors demonstrate (Table S1, supporting information), most of the excluded codes were either revisional procedures, adjuncts to primary surgery, or non‐specific/unspecified procedures. Inclusion of such codes may have resulted in the capture of non‐bariatric procedures, such as oesophagostomy, and revisional bariatric surgery, which may have different outcomes relative to those of primary bariatric procedures22 23.

Although data capture in the NHS is based on HES, it is known to have potential inaccuracies24. Regarding surgical procedures, this can occur through either missing or misidentifying patients. For instance, the HSCIC recently down‐adjusted the annual volume of bariatric surgery by several hundred patients due to the recording of gastric band adjustments in the clinic at one hospital as separate procedures25. In comparison with the present results, the NBSR (at the time a voluntary registry) reported 1052 primary bariatric procedures in 2009–20106. Such findings are likely to be sequelae of the current coding system. Although experienced and skilled, clinical coders assign codes based on their interpretation of the operative summary, notes or discharge letter26. This can lead to variability in the coding of similar procedures between coders and impact the case‐mix reported by HES26, 27, 28.

The process used to refine the plethora of potential bariatric codes to the 15 most relevant ones used in the present study highlights deficiencies in the current coding system. In the absence of linking data of actual patients between HES and the NBSR, investigators must rely on textual analysis of the code descriptions backed up with a survey of code usage to define a minimum set of bariatric codes, as used here. It is not feasible within data governance limitations to link actual patient data between the NBSR and HES. To prevent such coding variability and to ensure the HES database remains the standard, it is suggested that OPCS codes for bariatric surgery should be refined in accordance with the procedure descriptions in the NBSR Clinical Outcomes Reports. This needs greater input and involvement from bariatric surgeons. In support of this, for the 3 years from 2013 to 2016 the overall total case ascertainment for individual patient records submitted to the NBSR for NHS England was 92·5 per cent (20 534 of 22 199) of the HES‐recorded case volume14.

Bariatric surgery is associated with a low risk of procedure‐related death. The increased uptake of bariatric surgery in 2009–2016 within the English NHS has been safe. The perceived risk of bariatric surgery should not be seen as a barrier for severely obese patients seeking treatment.

Supporting information.

Additional supporting information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Supporting information

Table S1 OPCS codes and associated descriptors used to identify patients undergoing bariatric surgery for the present study and those utilized previously but excluded from the present study

Acknowledgements

The HES analysis in this study was funded by the Quality and Outcomes Research Unit, University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, commissioned by the National Bariatric Surgery Registry and funded indirectly by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership as part of the NHS Clinical Outcomes Publication Programme.

R.W. declares relevant financial activities outside the submitted work. This includes support for attending conferences and funding for a Bariatric Clinical Fellow at Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton, from Ethicon‐Endo Surgery, and the receipt of honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

Disclosure: The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Presented to the 20th World Congress of the International Federation for Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, Vienna, Austria, August 2015

Funding information

Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, NHS Clinical Outcomes Publication Programme

National Bariatric Surgery Registry

Quality and Outcomes Research Unit, University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust

References

- 1. Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) . Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet, England 2015. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB16988/obes-phys-acti-diet-eng-2015.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, Kashyap SR, Schauer PR, Mingrone G et al Bariatric surgery versus non‐surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2013; 347: f5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, Schauer PR, Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ et al Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 861–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Obesity: Identification, Assessment and Management. Clinical Guideline CG189; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG189 [accessed 5 September 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Welbourn R, le Roux CW, Owen‐Smith A, Wordsworth S, Blazeby JM. Why the NHS should do more bariatric surgery; how much should we do? BMJ 2016; 353: i1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Welbourn R, Small P, Finlay I, Sareela A, Somers S, Mahawar K et al The United Kingdom National Bariatric Surgery Registry. Second Registry Report 2014 Dendrite Clinical Systems: Henley, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahmad A, Laverty AA, Aasheim E, Majeed A, Millett C, Saxena S. Eligibility for bariatric surgery among adults in England: analysis of a national cross‐sectional survey. JRSM Open 2014; 5: 2042533313512479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burns EM, Naseem H, Bottle A, Lazzarino AI, Aylin P, Darzi A et al Introduction of laparoscopic bariatric surgery in England: observational population cohort study. BMJ 2010; 341: c4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) . Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) Analysis Guide; 2015. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/media/1592/HES-analysis-guide/pdf/HES_Analysis_Guide_Jan_2014.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) . Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet, England 2016, Appendices; 2016. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB20562/obes-phys-acti-diet-eng-2016-app.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) . A Guide to Linked Mortality Data from Hospital Episode Statistics and the Office for National Statistics; 2015. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/media/11668/HES-ONS-Mortality-Data-Guide/pdf/hes_ons__%20mortality_data_guide.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Welbourn R, Fiennes A, Kinsman R, Walton P. The United Kingdom National Bariatric Surgery Registry. First Registry Report to March 2010. Dendrite Clinical Systems: Henley, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) . Classification of Interventions and Procedures, 4th Revision (OPCS‐4) Codes Supplement; 2014. http://www.datadictionary.nhs.uk/web_site_content/supporting_information/clinical_coding/opcs_classification_of_interventions_and_procedures.asp [accessed 5 September 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hopkins JCA, Blazeby JM, Rogers CA, Welbourn R. The use of adjustable gastric bands for management of severe and complex obesity. Br Med Bull 2016; 118: 64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Bariatric Surgery Registry (NBSR) . Publication of Surgeon‐Level Data in the Public Domain for Bariatric Surgery in NHS England; 2017. http://www.bomss.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Bariatric-Surgery-Clinical-Outcomes-Publication-for-2015-16.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith MD, Patterson E, Wahed AS, Belle SH, Berk PD, Courcoulas AP et al Thirty‐day mortality after bariatric surgery: independently adjudicated causes of death in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2011; 21: 1687–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Birkmeyer NJO, Dimick JB, Share D, Hawasli A, English WJ, Genaw J et al Hospital complication rates with bariatric surgery in Michigan. JAMA 2010; 304: 435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang S‐H, Stoll CRT, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta‐analysis, 2003–2012. JAMA Surg 2014; 149: 275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Kashyap SR, Burguera B, Schauer PR. How safe is metabolic/diabetes surgery? Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17: 198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Böckelman C, Hahl T, Victorzon M. Mortality following bariatric surgery compared to other common operations in Finland during a 5‐year period (2009–2013). A nationwide registry study. Obes Surg 2017; 27: 2444–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reoch J, Mottillo S, Shimony A, Filion KB, Christou NV, Joseph L et al Safety of laparoscopic vs open bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arch Surg 2011; 146: 1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spyropoulos C, Kehagias I, Panagiotopoulos S, Mead N, Kalfarentzos F. Revisional bariatric surgery: 13‐year experience from a tertiary institution. Arch Surg [Internet] 2010; 145: 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park DP, Welch CA, Harrison DA, Palser TR, Cromwell DA, Gao F et al Outcomes following oesophagectomy in patients with oesophageal cancer: a secondary analysis of the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care 2009; 13(Suppl 2): S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. S Westaby, Archer N, Manning N, Adwani S, Grebenik C, Ormerod O et al Comparison of Hospital Episode Statistics and Central Cardiac Audit Database in public reporting of congenital heart surgery mortality. BMJ 2007; 335: 759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) . Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet Data Quality Statement, England 2015; 2015. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB16988/obes-phys-acti-diet-eng-2015-qual.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Spencer SA, Davies MP. Hospital Episode Statistics: improving the quality and value of hospital data: a national internet e‐survey of hospital consultants. BMJ Open 2012; 2: e001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hansell A, Bottle A, Shurlock L, Aylin P. Accessing and using hospital activity data. J Public Health 2001; 23: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dixon J, Sanderson C, Elliott P, Walls P, Jones J, Petticrew M. Assessment of the reproducibility of clinical coding in routinely collected hospital activity data: a study in two hospitals. J Public Health 1998; 20: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 OPCS codes and associated descriptors used to identify patients undergoing bariatric surgery for the present study and those utilized previously but excluded from the present study