Abstract

Background

Anal fistula occurs in approximately one in three patients with Crohn's disease and is typically managed through a multimodal approach. The optimal surgical therapy is not yet clear. The aim of this systematic review was to identify and assess the literature on surgical treatments of Crohn's anal fistula.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted that analysed studies relating to surgical treatment of Crohn's anal fistula published on MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane databases between January 1995 and March 2016. Studies reporting specific outcomes of patients treated for Crohn's anal fistula were included. The primary outcome was fistula healing rate. Bias was assessed using the Cochrane ROBINS‐I and ROB tool as appropriate.

Results

A total of 1628 citations were reviewed. Sixty‐three studies comprising 1584 patients were ultimately selected in the analyses. There was extensive reporting on the use of setons, advancement flaps and fistula plugs. Randomized trials were available only for stem cells and fistula plugs. There was inconsistency in outcome measures across studies, and a high degree of bias was noted.

Conclusion

Data describing surgical intervention for Crohn's anal fistula are heterogeneous with a high degree of bias. There is a clear need for standardization of outcomes and description of study cohorts for better understanding of treatment options.

Introduction

Crohn's disease affects an estimated 145 per 100 000 people in the UK1. One in three of these patients will develop a perianal fistula2, of whom just one in three achieve long‐term healing of the fistula3. This is a condition that should be managed in concert between surgeon and physician4. Published guidelines advocate sepsis control and use of anti‐tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α therapy5 6. Some patients improve or heal with this treatment, although many require further surgical intervention. The selected intervention may vary, depending on whether the treatment aim is cure or symptom relief.

Previous studies have shown that a range of surgical techniques are employed7. These include the use of a draining seton, anal fistula plug, fistulotomy, stoma creation and proctectomy. Newer techniques such as video‐assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT; Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) and over‐the‐scope clip (OTSC®; Ovesco Endoscopy, Tübingen, Germany) have also been introduced. This variation in practice suggests either that a widely acceptable and reproducible procedure has not yet been identified, or that additional factors may influence choice.

There is no current systematic assessment of all potential surgical interventions for the treatment of Crohn's anal fistula. The aim of this review was to collate data on the outcomes, including complications, of surgical interventions for the treatment of fistulating Crohn's anal disease.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search for all publications that reported a Crohn's anal fistula‐specific outcome, or surgical treatment outcomes of Crohn's anal fistula published between 1995 and March 2016 was performed. Since 1995, supporting medical therapy has changed significantly8. MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane Library databases were searched using a predefined and registered (PROSPERO database, CRD42016050316) search protocol. Original studies were eligible for inclusion. Hand‐searching was limited to bibliographies from identified systematic reviews following experiences in the pilot searches. Conference proceedings were included when related full text could be identified. Only papers in English were included. Manuscripts that reported outcomes of Crohn's anal fistula as part of all fistula types, those with fistula related to ileoanal pouch only, or outcomes of Crohn's rectovaginal fistula only, were excluded.

Terms used included ‘Crohn Disease’, ‘Rectal fistula’ or ‘anal fistula’, ‘surgery’, ‘Ligation of inter‐sphincteric fistula tract’ (LIFT), ‘seton’, ‘fistula plug’, ‘advancement flap’, ‘vaaft’, ‘OTSC’ ‘stoma’ and ‘proctectomy’ (Appendix S1, supporting information).

VAAFT involves insertion of a fistuloscope through the external opening of the track. Secondary tracks are then identified and electrocautery is performed through the scope. The internal opening is identified and closed using a full‐thickness advancement flap, with excision of the primary track where possible.

The OTSC® technique is performed in the lithotomy position. The track is prepared using a fistula brush. Anal mucosa is excised circumferentially around the internal fistula opening. Sutures are placed into the internal anal sphincter around the internal fistula opening and all tied loosely together in a knot with a few centimetres of length. The knot is then pulled through a clip applicator that guides a circular nitinol metal clip on to the internal fistula opening in order to close it.

Data extraction

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to retrieved citations by two independent reviewers. Abstracts were reviewed to identify full‐text papers. Two reviewers had to agree on inclusion of an abstract. The same process was repeated for full‐text articles. At this stage, the reason for exclusion was recorded.

Two reviewers recorded extracted data independently into a data collection form. These were compared and any variation was discussed with a third reviewer. Where data were missing or unclear, the corresponding author was contacted by e‐mail for clarification.

Data items collected included study descriptors, data on patient cohort, primary outcome used (including definition) and corresponding event rate. Study descriptors were year of publication, first author, study design, number of participants and number of participants with Crohn's disease, originating hospital and country of author. Patient descriptors included mean or median age of patient cohort, sex, duration of Crohn's disease, fistula anatomy (defined using either Parks' classification or the American Gastroenterological Association definition) and, where available, concurrent medical therapy. Intervention details focused on the primary surgical intervention, such as seton placement, LIFT procedure or fibrin glue. Primary outcome was taken as defined by each paper, as was the interval to assessment. Additional outcomes, including complications, were recorded as available together with rates of long‐term recurrence.

Quality analysis

The study was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines9. Risk of bias was assessed using the ROBINS‐I tool for non‐randomized interventions10, and the Cochrane tool for bias assessment in randomized trials11. Bias was assessed independently by two reviewers and then reconciled. Where there was disagreement, a third reviewer acted as an arbiter. The IDEAL (Idea, Development, Exploration, Assessment, Long‐term study) framework provides a means of categorizing the development stage of an intervention12. This allows categorization according to how technically developed a technique is, how well the indications are defined, what the risks and benefits of the procedure are, and long‐term follow‐up data. Studies were assessed by two authors and allocated to an IDEAL stage.

Statistical analysis

Although meta‐analyses of the data were originally intended, the paucity of RCTs and prevalence of small case series led to the decision to perform a qualitative synthesis only using descriptive statistics. No assessment of heterogeneity, publication bias or any other statistical assessment was planned. The primary outcome was fistula healing rate, defined as a reduction of 50 per cent or more from baseline in the number of draining fistulas observed at two or more consecutive study visits, as per the ACCENT‐II study8.

Results

Search results

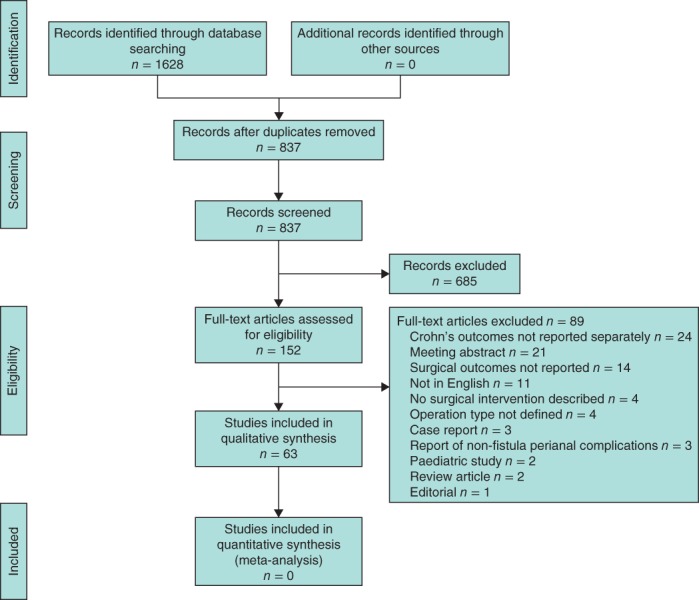

Initial literature review identified 1628 citations, of which 791 were duplicates. Screened against the eligibility criteria, full‐text manuscripts were retrieved and assessed. Of these 152 articles, 63 were included in the qualitative synthesis, reporting outcomes involving 1584 patients (Fig. 1). Study design was defined as retrospective cohort in 39 studies, as prospective cohort in 16, and as open‐label or single‐arm trial in five; there were three RCTs. The number of patients with Crohn's anal fistula ranged from two to 41 in prospective cohort studies, one to 119 in retrospective cohorts, and ten to 33 in open‐label/single‐arm trials. There were 141 patients in the randomized trials.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing selection of studies for review

The surgical interventions described were draining seton, examination under anaesthesia (EUA) with local anti‐TNFα therapy, fistulotomy, fistulectomy, fistula plug, fibrin glue, advancement flap, LIFT procedure, VAAFT, OTSC®, carbon dioxide laser therapy, diverting stoma and proctectomy. A summary of study characteristics is shown in Table 1, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Reference | Study design | Total no. of patients | No. of patients with Crohn's anal fistula | Intervention(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buchanan et al.13 | Retrospective cohort | 24 | 6 | Seton |

| Chung et al.14 | Retrospective cohort | 51 | 40 | Seton, AFP |

| Gligorijević et al.15 | Prospective cohort | 24 | 24 | Seton |

| Göttgens et al.16 | Pilot trial | 10 | 10 | Seton |

| Kotze et al.17 | Retrospective cohort | 78 | 78 | Seton |

| Sciaudone et al.18 | Retrospective cohort | 35 | 35 | Seton |

| Sugita et al.19 | Retrospective cohort | 67 | 67 | Seton |

| Tanaka et al.20 | Retrospective cohort | 14 | 14 | Seton |

| Uchino et al.21 | Retrospective cohort | 62 | 62 | Seton |

| Graf et al.22 | Retrospective cohort | 119 | 119 | Seton, fistulotomy |

| Thornton and Solomon23 | Retrospective cohort | 28 | 28 | Seton |

| Dursun et al.24 | Retrospective cohort | 81 | 81 | Seton, fistulotomy |

| Alessandroni et al.25 | Prospective cohort | 12 | 12 | Local anti‐TNFα |

| Asteria et al.26 | Prospective cohort | 11 | 11 | Local anti‐TNFα |

| Faucheron et al.27 | Retrospective cohort | 41 | 41 | Fistulotomy, seton |

| Halme and Sainio28 | Retrospective cohort | 35 | 35 | Fistulotomy |

| Scott and Northover29 | Retrospective cohort | 59 | 59 | Fistulotomy, seton |

| van Koperen et al.30 | Retrospective cohort | 61 | 61 | Fistulotomy, MAF |

| de Parades et al.31 | Retrospective cohort | 30 | 11 | Fibrin glue |

| Sentovich32 | Retrospective cohort | 48 | 6 | Fibrin glue |

| Sentovich33 | Retrospective cohort | 40 | 4 | Fibrin glue |

| Park et al.34 | Prospective cohort | 25 | 2 | Fibrin glue |

| Loungnarath et al.35 | Retrospective cohort | 39 | 13 | Fibrin glue |

| Zmora et al.36 | Retrospective cohort | 37 | 7 | Fibrin glue, MAF |

| Mizrahi et al.37 | Retrospective cohort | 106 | 28 | MAF |

| Hyman38 | Prospective cohort | 33 | 14 | MAF |

| Jarrar and Church39 | Retrospective cohort | 98 | 19 | MAF |

| Joo et al.40 | Retrospective cohort | 26 | 26 | MAF |

| Makowiec et al.41 | Prospective cohort | 32 | 32 | MAF |

| Ozuner et al.42 | Retrospective cohort | 101 | 47 | MAF |

| Rieger et al.43 | Retrospective cohort | 35 | 6 | MAF |

| Sonoda et al.44 | Retrospective cohort | 99 | 44 | MAF |

| Marchesa et al.45 | Retrospective cohort | 13 | 13 | MAF |

| Van der Hagen et al.46 | Retrospective cohort | 103 | 21 | MAF, fistulotomy |

| Nelson et al.47 | Retrospective cohort | 65 | 17 | Dermal advancement |

| Cintron et al.48 | Prospective cohort, multicentre | 73 | 8 | AFP |

| El‐Gazzaz et al.49 | Retrospective cohort | 33 | 13 | AFP |

| Ky et al.50 | Prospective cohort | 45 | 14 | AFP |

| O'Connor et al.51 | Prospective cohort | 20 | 20 | AFP |

| Ommer et al.52 | Retrospective cohort | 40 | 4 | AFP |

| Owen et al.53 | Retrospective cohort | 35 | 3 | AFP |

| Schwandner and Fuerst54 | Prospective cohort | 16 | 10 | AFP |

| Schwandner et al.55 | Prospective cohort | 19 | 7 | AFP |

| Senéjoux et al.56 | RCT | 106 | 106 | AFP, seton |

| Zubaidi and Al‐Obeed57 | Prospective cohort | 22 | 2 | AFP |

| Gingold et al.58 | Prospective cohort | 15 | 15 | LIFT |

| Molendijk et al.59 | Randomized phase II trial | 21 | 21 | MSC |

| Cho et al.60 | Phase I trial | 10 | 10 | ASC |

| Cho et al.61 | Prospective cohort | 41 | 41 | ASC |

| Ciccocioppo et al.62 | Phase I trial | 12 | 12 | MSC |

| de la Portilla et al.63 | Open‐label trial | 24 | 24 | ASC |

| Garcia‐Olmo et al.64 | Prospective cohort | 10 | 3 | ASC |

| Garcia‐Olmo et al.65 | Randomized open‐label trial | 49 | 14 | ASC, fibrin glue |

| Lee et al.66 | Phase II trial | 43 | 33 | ASC |

| Schwandner67 | Prospective cohort | 13 | 11 | VAAFT |

| Mennigen et al.68 | Retrospective cohort | 10 | 6 | OTSC® |

| Regueiro and Mardini69 | Retrospective cohort | 32 | 32 | EUA |

| Schlegel et al.70 | Retrospective cohort | 11 | 11 | IAR |

| Yamamoto et al.71 | Retrospective cohort | 31 | 31 | Stoma |

| Schaden et al.72 | Retrospective cohort | 69 | 5 | Myocutaneous flap |

| Ozturk73 | Retrospective cohort | 10 | 1 | Free cartilage |

| Bodzin74 | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 7 | Carbon dioxide laser |

| Moy and Bodzin75 | Retrospective cohort | 27 | 27 | Carbon dioxide laser |

AFP, anal fistula plug; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; MAF, mucosal advancement flap; LIFT, ligation of intersphincteric tract; MSC, mesenchyme‐derived stem cells; ASC, adipose‐derived stem cells; VAAFT, video‐assisted anal fistula treatment; OTSC, over‐the‐scope clip; EUA, examination under anaesthesia; IAR, intersphincteric anal resection.

Risk of bias within studies

Bias assessment for non‐randomized and randomized studies is shown in Tables S1 and S2 (supporting information). Overall, bias in non‐randomized studies tended to decrease as publication dates approached the present. Potential bias from confounders arose in studies with mixed populations (cryptoglandular and Crohn's fistula), with incomplete characterization of the cohort. This bias was reduced in cohorts limited to Crohn's fistula, where patient and disease factors were usually more clearly defined. Characterization was still suboptimal with regard to classification of fistulas, use of medical therapies, distribution of disease, smoking status and duration of perianal fistula.

Selection bias was an issue in retrospective studies that reported the outcomes of interventions in a single centre over a number of years. The criteria for offering interventions to patients were not clear: several studies stated that patients offered a procedure ‘typically’ had certain characteristics. Studies from teaching hospitals reported outcomes of patients referred to their centre, likely to introduce further selection bias.

Bias associated with the classification of interventions tended to be low in studies reporting outcomes from one specific procedure. The details of the procedure and perioperative care were clear. In studies reporting the use of setons, some issues arose around the timing of removal, whether setons were removed or not, and the timing and nature of concurrent medical therapy15 17.

Outcome measurement was highly variable. Many studies reported healing, without clear definition, as their primary outcome. Other commonly reported measures included absence of drainage from a fistula when compressed with a finger56, or closure of the external and internal opening of a fistula track at variable time points. Occasional use of MRI to confirm fistula fibrosis was reported25. One study29 reported a successful outcome as ‘the patient and surgeon are both satisfied’. Only one study56 had blinded assessors – a panel of three surgeons who reviewed perineal photographs to confirm fistula closure.

In the randomized trials, the main concerns involved allocation concealment and blinding of participants. One stem cell study65 had patients allocated to receive liposuction to harvest cells only if they were in the intervention arm. Overall, these trials were of good quality.

Results of studies

A summary of the key outcomes by intervention is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of key outcomes by intervention, including classification of level of evidence76

| Intervention | Highest level of evidence | Success rate (%) | Complication rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seton | IIb | 14–81 | Abscess 7–8 |

| Fistulotomy | IIIb | 72–100 | n.r. |

| Fibrin glue | IIIb | 40–67 | n.r. |

| Anal fistula plug | IIb | 15–86 | Abscess 4–54 |

| Avulsion 10 | |||

| Dehiscence 2 | |||

| Advancement flap | IIIc | 50–85 | Haematoma 7 |

| Flap retraction 7 | |||

| LIFT procedure | IV | 60 | n.r. |

| Local stem cells | Ib | 29–79 | Pain 19 |

| Anal inflammation 7 | |||

| Abscess 17–19 | |||

| VAAFT | IV | 8 | n.r. |

| OTSC® | IV | 83 | n.r. |

| Stoma | IIc | 81 | Death 5 |

| Stoma complication 16 |

n.r., Not reported (used where no outcomes reported, or outcomes in patients with Crohn's disease not clear); LIFT, ligation of intersphincteric tract; VAAFT, video‐assisted anal fistula treatment; OTSC, over‐the‐scope clip.

Outcomes after seton insertion

Setons were used in a number of different ways. Use of a seton alone, with removal at various time points, was reported in six retrospective fistula cohort studies13 14, 18 19, 21 22, and included a total of 329 Crohn's fistulas. In the four studies14 18, 19 22 assessing short‐term healing, success rates ranged from 14 to 81 per cent. One study21 looked at symptom improvement, defined as improvement by at least 1 point in all domains of the perianal disease activity index. This endpoint was achieved in 72 per cent of patients. Long‐term recurrence was reported in 43 per cent18 and 83 per cent13 of patients. Further drainage of abscess was required in 42·8 per cent19, and in one study21 two patients developed a cancer related to the fistula.

Long‐term setons were used for symptom control in one study23 of 28 patients, of whom 26 noted symptomatic improvement. The two patients without improvement went on to have a proctectomy or defunctioning stoma.

Seton therapy combined with anti‐TNFα therapy was the focus of two retrospective cohort studies17 20 and one prospective cohort study15, accounting for a total of 116 patients. There was incomplete characterization of group demographics. The timing of anti‐TNFα therapy in relation to sepsis drainage or seton insertion was not clear in these studies. Short‐term success was defined as absence of drainage in two studies15 17 (although the time point for measurement was unclear) and complete fistula healing in one20. These outcomes were achieved in 46 per cent15, 53 per cent17 and 79 per cent20 of patients. Recurrence rates, where reported, were between 9 and 28 per cent15 20. Abscesses occurred in up to 8 per cent15. One study20 reported no serious adverse effects related to systemic drug therapy. Seton with anti‐TNFα therapy also formed the control arm of a randomized trial56, which found short‐term healing in 30·7 per cent of patients, with a recurrent abscess rate of 7·7 per cent.

Examination under anaesthesia with local or systemic anti‐TNFα therapy

Two prospective studies25 26 assessed responses to EUA and local injection of anti‐TNFα drugs. In one study26, 11 patients received between three and five injections, and eight patients achieved remission (cessation of fistula drainage) at the end of the treatment course. In the second study25, 12 patients with Crohn's anal fistula underwent fistulectomy and local anti‐TNFα injection. Definition of healing was based on clinical and MRI appearances at 1 year. With four patients lost to follow‐up, healing was achieved in seven patients (88 (95 per cent c.i. 48 to 100) per cent). One patient developed a new perianal abscess and another developed pulmonary tuberculosis after treatment25.

One retrospective study69 assessed the use of EUA as an adjunct to systemic anti‐TNFα therapy, and found no discharge from fistulas at 3 months, although subsequent recurrence occurred in 44 per cent.

Fistulotomy

Seven retrospective studies22 24, 27, 28, 29, 30 46 reported on the outcomes of fistulotomy in 148 patients. Although baseline factors were poorly reported, these were typically for low fistulas – those involving a small part of sphincter where division would not alter function. Outcomes were defined as initial healing22 or 3‐month healing24.

Short‐term healing was successful in 72–100 per cent of patients22 24, 27 28. Longer‐term (6 months or more after treatment) fistula recurrence occurred in five of 28 patients30 and three of nine patients46 at 12 months. One study29 found that 22 of 27 patients had a ‘satisfactory’ outcome, although the five patients in whom the outcome was unsuccessful developed significant incontinence. Higher rates of continence disturbance were seen in other studies30.

Fibrin glue

Six studies (five retrospective31, 32, 33 35, 36 and one prospective34) included 219 patients, but only 43 of these had Crohn's disease. Short‐term success rates for fibrin glue ranged from 40 to 67 per cent31 33, 34 36. In one study32 reporting long‐term follow‐up, three of four patients remained healed.

Fistula plug

Results of anal fistula plug were reported in 11 studies including 191 patients with Crohn's anal fistula. Study design included one RCT56, six prospective cohort studies48 50, 51 54, 55 57 and four retrospective cohort studies14 49, 52 53. In the cohort studies, follow‐up ranged from 0·75 to 29 months after the procedure. Definition of demographics was poor in these studies, and included 14 patients with a complex fistula in one study50 (including 4 rectovaginal fistulas), and patients with a single transphincteric track and no proctitis in another55. In the RCT, the American Gastroenterological Association classification77 was used, and included 18 patients with a complex fistula and 78 with a simple fistula. Ratios of men to women were 3 : 1 and 41 : 68 where reported, and age ranged from 26 to 43 years. Disease duration before the RCT was 3–13 years. One study54 included the use of faecal diversion in addition to the anal fistula plug in some patients.

Success rates for the fistula plug technique ranged from 15 to 86 per cent. Where reported49 50, 52 56, postoperative abscess formation occurred in 4–54 per cent of patients. Additional complications included one wound dehiscence52, five plug extrusions and two episodes of significant pain56.

Advancement flaps

Eight retrospective30 37, 39 40, 42, 43, 44 46 and two prospective observational38 41 studies reported the outcome of mucosal advancement flaps in both Crohn's and cryptoglandular perianal fistulous disease. Of the 590 reported procedures, 204 were performed for Crohn's fistula. Where reported, treated fistulas were predominantly transphincteric, although studies included some rectovaginal fistulas.

Success in short‐term healing was observed in 50–85 per cent of patients. Where reported38 46, the recurrence rate at more than 1 year was 30–50 per cent. Complications were reported in only one study40, with haemorrhage and flap retraction occurring in 7 per cent.

A retrospective study45 reported on the use of a circumferential advancement flap for severe and multiple fistula tracks in 13 patients, combined with stoma formation in eight. This led to symptomatic improvement in eight patients, although all patients also had a stoma either before or as part of the procedure.

One retrospective study47 reported on the use of dermal flaps to close the fistula opening, with 15 of 17 patients achieving short‐term healing.

An augmented approach was used in a pilot trial16. This involved placement of a seton, followed by local treatment with platelet‐rich plasma and mucosal advancement flap. Participants also received multiple concomitant medical therapies. At 1‐year follow‐up, seven of the ten patients had a dry fistula.

Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract procedure

One study58 reported the outcomes of patients undergoing the LIFT procedure. This was a retrospective study of 15 patients with transphincteric fistula, followed up for 1 year. At 2‐month follow‐up, nine (60 per cent) had healed, and eight of these remained healed at 1 year. Complications such as abscess were reported for this study; however, they were calculated as mean numbers for the cohort. The author was contacted, but data from this study were no longer available.

Stem cell therapy

Six studies reported the outcome of stem cell therapy; five open label/phase I or II trials59 60, 63 65, 66, with longer‐term follow‐up61 of the cohort initially reported by Cho et al.60 in 2013. These studies assessed adipose‐derived stem cells in 143 patients. One phase I trial62 reported outcomes of mesenchymal stem cell treatment in 12 patients. Follow‐up in these studies ranged from 8 weeks to 24 months. Cohorts were dominated by men and young patients, with a median age of about 32 years in several studies. Duration of Crohn's disease was approximately 4·5 years where reported. Most fistulas were transphincteric. Success rates for healing ranged from 29 to 79 per cent. Improvement in symptoms was noted in a large proportion of patients. This was assessed at 8 weeks60, defined as a variable time point of ‘no discharge for 6 weeks’59, or at clinic appointments at 12 and 24 months61.

Symptoms associated with disease flare, such as abdominal pain and diarrhoea, were reported in up to 60 per cent66 and 7 per cent61 respectively. Local complications included anal pain in 19 per cent66, anal inflammation in 7 per cent61, perianal swelling in 29 per cent59 and perianal abscess in 17–19 per cent59 66 of patients.

A single study64 of recurrent anal fistula with a subgroup of three patients with Crohn's disease found that one patient healed and one improved when adipose‐derived stem cells were injected into the fistula and the internal opening was closed.

Video‐assisted anal fistula treatment

One prospective study67 reported outcomes of patients treated with VAAFT. Thirteen patients were treated, of whom 11 had anal fistula related to Crohn's disease. Of these 11 fistulas, nine were transphincteric, one was suprasphincteric and one was rectovaginal. The mean age of patients was 34 years. This study67 combined VAAFT with rectal advancement flap and faecal diversion. ‘Short‐term success’ was achieved in nine patients. There was no reporting of complications.

Over‐the‐scope clip (OTSC®)

A single case series68 reported the use of OTSC® in anal fistula. Of the ten patients treated, six had fistula associated with Crohn's disease. Four were women, and all had a transphincteric fistula. No information was available on mean duration of disease. Median follow‐up was 230·5 (range 156–523) days. The study reported short‐term healing in five of the six patients with Crohn's disease. It was not possible to extract complications specific to treated patients with Crohn's fistula.

Proctectomy and diversion

One retrospective study70 reported the use of intersphincteric anal resection (IAR) for fistulating and fibrosing perianal Crohn's disease. In this series, 11 patients underwent IAR and five achieved closure of the fistula. Another retrospective study72 assessed outcomes of proctectomy with one‐stage myocutaneous reconstruction (gracilis) in five patients. Perianal fistula healed in four cases, and only two patients were free from complications at the end of follow‐up (median 19·6 months).

Faecal diversion was reported as a sole intervention in a series of 31 patients71. In this cohort, 25 patients achieved early remission, although this was sustained in only eight (median follow‐up 81 months). One patient died as a result of Fournier's gangrene and five developed stoma complications, of whom two required operative revision. No patient developed malignancy in the defunctioned rectum71.

Other therapies

One retrospective study75 reported outcomes of patients treated with carbon dioxide laser to the fistula track. This included 27 patients, with a mean duration of disease of 36 months. At 1‐month follow‐up, four patients had ceased fistula drainage. Another retrospective study74 found that laser treatment healed or improved symptoms in five of six patients. One other study73 assessed the use of free cartilage as an interposition material in Crohn's fistula. This was unsuccessful.

Grading according to the IDEAL framework

Only seton, fistulotomy and faecal diversion/proctectomy are classified as IDEAL 4 interventions. The majority of interventions are classified as IDEAL 1–2b interventions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Interventions classified by the IDEAL framework

| IDEAL stage | Intervention |

|---|---|

| 1 (Idea) | Circumferential advancement flap |

| VAAFT | |

| OTSC® | |

| Free cartilage | |

| 2a (Development) | Local anti‐TNFα injection |

| LIFT | |

| Carbon dioxide laser | |

| 2b (Exploration) | Local stem cell therapy |

| Mucosal advancement flap | |

| Fibrin glue | |

| 3 (Assessment) | Anal fistula plug |

| 4 (Long‐term study) | Seton |

| Fistulotomy | |

| Stoma/proctectomy |

VAAFT, video‐assisted anal fistula treatment; OTSC, over‐the‐scope clip; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; LIFT, ligation of intersphincteric tract.

Discussion

Advances in the medical therapy of fistulating perianal Crohn's disease have been boosted by large RCTs8 78, 79. The present study has highlighted a number of important features regarding surgical interventions. The level of evidence supporting these interventions was generally low. Studies often captured specific subsets of patients, and selection bias means that reported results are not always matched by real‐world experience. The lack of a classification system with prognostic value means that a benefit produced in one (unknown and undefined) cohort may be masked by failure in another. Options for surgical management of Crohn's anal fistula, including seton insertion, advancement flap, anal fistula plug and stem cells, have been used in several studies, although success rates vary. Only three RCTs comparing therapies were retrieved. It should be noted that a number of feasibility studies were performed, particularly in relation to local stem cell therapy. Since searches for this review were performed, a randomized trial of stem cells has been reported80. A randomized trial of advancement flap versus seton drainage in the context of protocolled medical therapy is underway81.

Meta‐analyses were not appropriate for these data. The IDEAL classification was used to grade the interventions. Part of the categorization used in the IDEAL framework is the number and type of patients, with ‘indication’ being an important discriminator12. Although draining setons, fistulotomy and faecal diversion seem to have broadly agreed indications with long‐term follow‐up, this does not appear to be the case for other interventions. Classification of fistula anatomy varies between the Hughes–Cardiff classification82, Parks classification83 and American Gastroenterological Association definitions77. It is not always possible to consolidate these classifications. Some studies also specified whether or not patients had proctitis55, as this is thought to be relevant to prognosis5 6.

Current thinking suggests that optimal therapy involves a combined medical and surgical strategy. Smaller case series often described the current medical therapy of their patients, but larger retrospective studies typically failed to report this.

It was impossible to make meaningful comparisons of success rates between interventions, as selected outcomes and time points were heterogeneous. Pooled analysis was hampered by the bias inherent in the preponderance of retrospective studies, and the limited size of their cohorts. It was impossible to compare risk between the operative procedures, as reporting of complications was very poor, with the exception of clinical trials. Some studies30 71 also reported ‘long‐term recurrence’ at the end of their follow‐up period as late as 6–8 years, but was this truly recurrence due to the surgical procedure or simply the natural history of the disease?

Only broad conclusions can be drawn from the present study. Setons provide palliation and can be used in the long term; advancement flap and stem cell therapy may emerge as effective therapies, but require well designed randomized trials. A number of other procedures including LIFT, VAAFT and OTSC® require further evaluation.

Fibrin glue has largely fallen out of favour, and fistula plugs are considered to have limitations, including failure and associated sepsis. Advancement flaps may not be technically possible with a ‘woody’ rectum, extensive fibrosis or active proctitis. The combination of recurrent Crohn's disease and loose stool means that any sphincter disruption or alteration in anocutaneous sensation may have an exaggerated impact on continence. Clinicians and patients may therefore understandably be keen to avoid procedures that pose additional risk to the sphincter, including fistulotomy. Given these technical considerations, fistula anatomy and the risk of recurrent episodes of anal perianal sepsis, including fistula in the long term, it is unsurprising that most clinicians favour conservative interventions such as seton placement7.

When considering these studies together, especially over longer‐term follow‐up, it may be inferred that Crohn's anal fistula is at best palliated by surgical intervention. Most studies report success in terms of short‐term healing, and have not addressed the management or prevention of long‐term recurrence. Although the idea of healing anal fistula is aspirational, work is required to understand how to control symptoms and limit recurrence with medical and surgical techniques. Patient‐centred outcomes such as data on quality of life, impact on personal and social interactions, or lost work‐days may be more helpful in decision‐making. For example, faecal diversion has been shown to improve gastrointestine‐specific domains of quality‐of‐life measures in this setting84.

Work needs to be done to improve the quality of evidence for every type of surgical intervention. Transparent and thorough reporting on studies involving these patients is warranted. There needs to be international agreement on definitions to facilitate comparisons between institutions. Development and adoption of a core outcome set, including a validated, disease‐specific quality‐of‐life score, would help. A classification system based on prognostic factors, and improved therapeutic options based on an understanding of the current mechanisms of treatment failure, are both crucial.

Collaborators

Other ENiGMA Collaborators are: A. Hart, A. J. Lobo, S. Sebastian (gastroenterology), P. Sagar, S. P. Bach, A. McNair (surgery), A. Verjee, S. Blackwell (patient representatives), P. F. C. Lung (radiology) and D. Hind (Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit).

Supporting information

Appendix S1 MEDLINE search via PubMed

Table S1 a–c Risk‐of‐bias assessment of non‐randomized studies using the ROBINS‐I tool10

Table S2 Risk‐of‐bias assessment of randomized studies using the Cochrane risk of bias in randomized trials tool11

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken as part of work funded by the Bowel Disease Research Foundation.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

M. J. Lee, Email: m.j.lee@sheffield.ac.uk.

ENiGMA Collaborators:

A. Hart, A. J. Lobo, S. Sebastian, P. Sagar, S. P. Bach, A. McNair, A. Verjee, S. Blackwell, P. F. C. Lung, and D. Hind

References

- 1. Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R et al; IBD Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2011; 60: 571–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Safar B, Sands D. Perianal Crohn's disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2007; 20: 282–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Molendijk I, Nuij V, van der Meulen‐de Jong A, van der Woude C. Disappointing durable remission rates in complex Crohn's disease fistula. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20: 2022–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yassin NA, Askari A, Warusavitarne J, Faiz OD, Athanasiou T, Phillips RK et al Systematic review: the combined surgical and medical treatment of fistulising perianal Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 40: 741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, van der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M et al; European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). The second European evidence‐based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: special situations. J Crohns Colitis 2010; 4: 63–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gecse K, Bemelman W, Kamm M, Stoker J, Khanna R, Ng SC et al; World Gastroenterology Organization; International Organisation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IOIBD); European Society of Coloproctology and Robarts Clinical Trials. A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn's disease. Gut 2014; 63: 1381–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee MJ, Heywood N, Sagar PM, Brown SR, Fearnhead NS; Collaborators pCD. Surgical management of fistulating perianal Crohn's disease – a UK survey. Colorectal Dis 2017; 19: 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Present D, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA et al Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1398–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M et al ROBINS‐I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non‐randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016; 355: i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higgins JPT, Green S (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration: Copenhagen, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCulloch P, Altman DG, Campbell WB, Flum DR, Glasziou P, Marshall JC et al No surgical innovation without evaluation: the IDEAL recommendations. Lancet 2009; 374: 1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buchanan GN, Owen HA, Torkington J, Lunniss PJ, Nicholls RJ, Cohen CR. Long‐term outcome following loose‐seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. Br J Surg 2004; 91: 476–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chung W, Ko D, Sun C, Raval MJ, Brown CJ, Phang PT. Outcomes of anal fistula surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Surg 2010; 199: 609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gligorijević V, Spasić N, Bojić D, Protić M, Svorcan P, Maksimovic B et al The role of pelvic MRI in assessment of combined surgical and infliximab treatment for perianal Crohn's disease. Acta Chir Iugosl 2010; 57: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Göttgens KW, Smeets RR, Stassen LP, Beets GL, Pierik M, Breukink SO. Treatment of Crohn's disease‐related high perianal fistulas combining the mucosa advancement flap with platelet‐rich plasma: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19: 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kotze PG, Albuquerque I, Moreira A, Tonini WB, Olandoski M, Coy CSR. Perianal complete remission with combined therapy (seton placement and anti‐TNF agents) in Crohn's disease: a Brazilian multicenter observational study. Arq Gastroenterol 2014; 51: 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sciaudone G, Di Stazio C, Limongelli P, Guadagni I, Pellino G, Riegler G et al Treatment of complex perianal fistulas in Crohn disease: infliximab, surgery or combined approach. Can J Surg 2010; 53: 299–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sugita A, Koganei K, Harada H, Yamazaki Y, Fukushima T, Shimada H. Surgery for Crohn's anal fistulas. J Gastroenterol 1995; 30(Suppl 8): 143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tanaka S, Matsuo K, Sasaki T, Nakano M, Sakai K, Beppu R et al Clinical advantages of combined seton placement and infliximab maintenance therapy for perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease: when and how were the seton drains removed? Hepatogastroenterology 2010; 57: 3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Bando T, Matsuoka H, Takesue Y, Takahashi Y et al Long‐term efficacy of infliximab maintenance therapy for perianal Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17: 1174–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Graf W, Andersson M, Åkerlund JE, Börjesson L; Swedish Organization for Studies of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Long‐term outcome after surgery for Crohn's anal fistula. Colorectal Dis 2016; 18: 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thornton M, Solomon MJ. Long‐term indwelling seton for complex anal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dursun A, Hodin R, Bordeianou L. Impact of perineal Crohn's disease on utilization of care in the absence of modifiable predictors of treatment failure. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014; 29: 1535–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alessandroni L, Kohn A, Cosintino R, Marrollo M, Papi C, Monterubbianesi R et al Local injection of infliximab in severe fistulating perianal Crohn's disease: an open uncontrolled study. Tech Coloproctol 2011; 15: 407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Asteria CR, Ficari F, Bagnoli S, Milla M, Tonelli F. Treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease by local injection of antibody to TNF‐alpha accounts for a favourable clinical response in selected cases: a pilot study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006; 41: 1064–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Faucheron JL, Saint‐Marc O, Guibert L, Parc R. Long‐term seton drainage for high anal fistulas in Crohn's disease – a sphincter‐saving operation? Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 208–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Halme L, Sainio AP. Factors related to frequency, type, and outcome of anal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum 1995; 38: 55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scott HJ, Northover JM. Evaluation of surgery for perianal Crohn's fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van Koperen PJ, Safiruddin F, Bemelman WA, Slors JF. Outcome of surgical treatment for fistula in ano in Crohn's disease. Br J Surg 2009; 96: 675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Parades V, Far HS, Etienney I, Zeitoun JD, Atienza P, Bauer P. Seton drainage and fibrin glue injection for complex anal fistulas. Colorectal Dis 2010; 12: 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sentovich SM. Fibrin glue for anal fistulas: long‐term results. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sentovich SM. Fibrin glue for all anal fistulas. J Gastrointest Surg 2001; 5: 158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Park JJ, Cintron JR, Orsay CP, Pearl RK, Nelson RL, Sone J et al Repair of chronic anorectal fistulae using commercial fibrin sealant. Arch Surg 2000; 135: 166–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loungnarath R, Dietz DW, Mutch MG, Birnbaum EH, Kodner IJ, Fleshman JW. Fibrin glue treatment of complex anal fistulas has low success rate. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 432–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zmora O, Mizrahi N, Rotholtz N, Pikarsky AJ, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ et al Fibrin glue sealing in the treatment of perineal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 584–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mizrahi N, Wexner SD, Zmora O, Da Silva G, Efron J, Weiss EG et al Endorectal advancement flap: are there predictors of failure? Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 1616–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hyman N. Endoanal advancement flap repair for complex anorectal fistulas. Am J Surg 1999; 178: 337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jarrar A, Church J. Advancement flap repair: a good option for complex anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2011; 54: 1537–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Joo JS, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Endorectal advancement flap in perianal Crohn's disease. Am Surg 1998; 64: 147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Becker HD, Starlinger M. Clinical course after transanal advancement flap repair of perianal fistula in patients with Crohn's disease. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ozuner G, Hull TL, Cartmill J, Fazio VW. Long‐term analysis of the use of transanal rectal advancement flaps for complicated anorectal/vaginal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rieger NA, Stitz RW, Lumley JW. Full thickness transrectal advancement flap for high anal fistula. Colorectal Dis 1999; 1: 238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sonoda T, Hull T, Piedmonte MR, Fazio VW. Outcomes of primary repair of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas using the endorectal advancement flap. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 1622–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marchesa P, Hull TL, Fazio VW. Advancement sleeve flaps for treatment of severe perianal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 1695–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van der Hagen SJ, Baeten CG, Soeters PB, van Gemert WG. Long‐term outcome following mucosal advancement flap for high perianal fistulas and fistulotomy for low perianal fistulas: recurrent perianal fistulas: failure of treatment or recurrent patient disease? Int J Colorectal Dis 2006; 21: 784–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nelson RL, Cintron J, Abcarian H. Dermal island‐flap anoplasty for transsphincteric fistula‐in‐ano: assessment of treatment failures. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 681–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cintron JR, Abcarian H, Chaudhry V, Singer M, Hunt S, Birnbaum E et al Treatment of fistula‐in‐ano using a porcine small intestinal submucosa anal fistula plug. Tech Coloproctol 2013; 17: 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. El‐Gazzaz G, Zutshi M, Hull T. A retrospective review of chronic anal fistulae treated by anal fistulae plug. Colorectal Dis 2010; 12: 442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ky AJ, Sylla P, Steinhagen R, Steinhagen E, Khaitov S, Ly EK. Collagen fistula plug for the treatment of anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2008; 51: 838–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O'Connor L, Champagne BJ, Ferguson MA, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of Crohn's anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; 49: 1569–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ommer A, Herold A, Joos A, Schmidt C, Weyand G, Bussen D. Gore BioA Fistula Plug in the treatment of high anal fistulas – initial results from a German multicenter‐study. Ger Med Sci 2012; 10: Doc13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Owen G, Keshava A, Stewart P, Patterson J, Chapuis P, Bokey E et al Plugs unplugged. Anal fistula plug: the Concord experience. ANZ J Surg 2010; 80: 341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schwandner O, Fuerst A. Preliminary results on efficacy in closure of transsphincteric and rectovaginal fistulas associated with Crohn's disease using new biomaterials. Surg Innov 2009; 16: 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schwandner O, Stadler F, Dietl O, Wirsching RP, Fuerst A. Initial experience on efficacy in closure of cryptoglandular and Crohn's transsphincteric fistulas by the use of the anal fistula plug. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008; 23: 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Senéjoux A, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, Munoz‐Bongrand N, Desseaux K, Bouguen G et al; Groupe d'Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif [GETAID]. Fistula plug in fistulising ano‐perineal Crohn's disease: a randomised controlled trial. J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10: 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zubaidi A, Al‐Obeed O. Anal fistula plug in high fistula‐in‐ano: an early Saudi experience. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 1584–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gingold DS, Murrell ZA, Fleshner PR. A prospective evaluation of the ligation of the intersphincteric tract procedure for complex anal fistula in patients with Crohn's disease. Ann Surg 2014; 260: 1057–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Molendijk I, Bonsing BA, Roelofs H, Peeters KC, Wasser MN, Dijkstra G et al Allogeneic bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells promote healing of refractory perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 918–927.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cho YB, Lee WY, Park KJ, Kim M, Yoo HW, Yu CS. Autologous adipose tissue‐derived stem cells for the treatment of Crohn's fistula: a phase I clinical study. Cell Transplant 2013; 22: 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cho YB, Park KJ, Yoon SN, Song KH, Kim DS, Jung SH et al Long‐term results of adipose‐derived stem cell therapy for the treatment of Crohn's fistula. Stem Cells Transl Med 2015; 4: 532–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ciccocioppo R, Bernardo ME, Sgarella A, Maccario R, Avanzini MA, Ubezio C et al Autologous bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of fistulising Crohn's disease. Gut 2011; 60: 788–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. de la Portilla F, Alba F, García‐Olmo D, Herrerías JM, González FX, Galindo A. Expanded allogeneic adipose‐derived stem cells (eASCs) for the treatment of complex perianal fistula in Crohn's disease: results from a multicenter phase I/IIa clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013; 28: 313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Garcia‐Olmo D, Guadalajara H, Rubio‐Perez I, Herreros MD, de‐la‐Quintana P, Garcia‐Arranz M. Recurrent anal fistulae: limited surgery supported by stem cells. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 3330–3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Garcia‐Olmo D, Herreros D, Pascual I, Pascual JA, Del‐Valle E, Zorrilla J et al Expanded adipose‐derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula: a phase II clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lee WY, Park KJ, Cho YB, Yoon SN, Song KH, Kim DS et al Autologous adipose tissue‐derived stem cells treatment demonstrated favorable and sustainable therapeutic effect for Crohn's fistula. Stem Cells 2013; 31: 2575–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schwandner O. Video‐assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) combined with advancement flap repair in Crohn's disease. Tech Coloproctol 2013; 17: 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mennigen R, Laukötter M, Senninger N, Rijcken E. The OTSC® proctology clip system for the closure of refractory anal fistulas. Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19: 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Regueiro M, Mardini H. Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease with infliximab alone or as an adjunct to exam under anesthesia with seton placement. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2003; 9: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schlegel N, Kim M, Reibetanz J, Krajinovic K, Germer CT, Isbert C. Sphincter‐sparing intersphincteric rectal resection as an alternative to proctectomy in long‐standing fistulizing and stenotic Crohn's proctitis? Int J Colorectal Dis 2015; 30: 655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MR. Effect of fecal diversion alone on perianal Crohn's disease. World J Surg 2000; 24: 1258–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schaden D, Schauer G, Haas F, Berger A. Myocutaneous flaps and proctocolectomy in severe perianal Crohn's disease – a single stage procedure. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007; 22: 1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ozturk E. Treatment of recurrent anal fistula using an autologous cartilage plug: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19: 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bodzin JH. Laser ablation of complex perianal fistulas preserves continence and is a rectum‐sparing alternative in Crohn's disease patients. Am Surg 1998; 64: 627–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Moy J, Bodzin J. Carbon dioxide laser ablation of perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease: experience with 27 patients. Am J Surg 2006; 191: 424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, Greenhalgh T, Heneghan C, Liberati A et al The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence (Introductory Document) Oxford Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine: Oxford, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 77. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee . American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2003; 125: 1503–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Colombel J, Sandborn W, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R et al Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn's disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 52–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sandborn W, Feagan B, Stoinov S, Honiball PJ, Rutgeerts P, Mason D et al; PRECISE 1 Study Investigators. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2007; 19: 228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Panés J, García‐Olmo D, Van Assche G, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Baumgart DC et al; ADMIRE CD Study Group Collaborators. Expanded allogeneic adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: a phase 3 randomised, double‐blind controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 1281–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. de Groof EJ, Buskens CJ, Ponsioen CY, Dijkgraaf MG, D'Haens GR, Srivastava N et al Multimodal treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: seton versus anti‐TNF versus advancement plasty (PISA): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015; 16: 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hughes L. Clinical classification of perianal Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum 1992; 35: 928–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Parks A, Gordon P, Hardcastle J. A classification of fistula‐in‐ano . Br J Surg 1976; 63: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kasparek MS, Glatzle J, Temeltcheva T, Mueller MH, Koenigsrainer A, Kreis ME. Long‐term quality of life in patients with Crohn's disease and perianal fistulas: influence of fecal diversion. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50: 2067–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 MEDLINE search via PubMed

Table S1 a–c Risk‐of‐bias assessment of non‐randomized studies using the ROBINS‐I tool10

Table S2 Risk‐of‐bias assessment of randomized studies using the Cochrane risk of bias in randomized trials tool11