Abstract

Background

The specificity of clinical questions is gauged by explicit descriptions of four dimensions: subjects, interventions, comparators and outcomes of interest. This study determined whether adding simple instructions and examples on clinical question formulation would increase the specificity of the submitted question compared to using a standard form without instructions and examples.

Methods

A randomised controlled trial was conducted in an evidence-search and appraisal service. New participants were invited to reformulate clinical queries. The Control Group was given no instructions. The Intervention Group was given a brief explanation of proper formulation, written instructions, and diagrammatic examples. The primary outcome was the change in the proportion of reformulated questions that described each the dimensions of specificity.

Results

Fifty-two subjects agreed to participate in the trial of which 13 were lost to follow-up. The remaining 17 Intervention Group and 22 Control Group participants were analysed. Baseline characteristics were comparable. Overall, 20% of initially submitted questions from both groups were properly specified (defined as an explicit statement describing all dimensions of specificity). On follow-up, 7/14 questions previously rated as mis-specified in the Intervention Group had all dimensions described at follow-up (p = 0.008) while the Control Group did not show any changes from baseline. Participants in the Intervention Group were also more likely to explicitly describe patients (p = 0.028), comparisons (p = 0.014), and outcomes (p = 0.008).

Conclusions

This trial demonstrated the positive impact of specific instructions on the proportion of properly-specified clinical queries. The evaluation of the long-term impact of such changes is an area of continued research.

Background

Providing a foundation of evidence to facilitate practice change or to reinforce current practice requires the formulation of specific, relevant questions that are answerable within the bounds of current research methods. This first step – the generation of a focused question – is crucial in many respects. On the one hand, a clearly defined question makes transparent the forethought invested in planning and conducting the research because it readily demarcates the boundaries of the study, clearly defines its significance in relation to previous work, and suggests appropriate methods to examine the problem. On the other hand, research stemming from poorly-defined questions often is unclear about its objectives, applies inappropriate methods in its pursuit of nebulous ideas, is vague in its proposed outcomes and, hence, is liable to be too far reaching in its conclusions.

In the context of the current paradigm of evidence based health care, a focused clinical question is advocated as the starting point from which findings from research are integrated with clinical experience and patient preferences to come to some shared decision about the management of disease or the promotion of health [1].

We define a focused clinical question as a clinical- or practice-based query that is important, relevant, and specific. The importance and relevance of an issue depend on the area of research or clinical practice, with patients often providing insight into the most significant or pertinent aspects of the clinical encounter [2,3]. Specificity is related to the fulfilment of certain criteria that allow the question to be dissected into discrete fragments [4]. Each fragment contributes to the overall demarcation of a particular area of study and consists of a minimum of four dimensions: the subjects on which the research was conducted, the intervention of interest, the comparator against which the intervention was evaluated, and the outcomes of interest [4-6].

Each of the four dimensions are descriptive in their terms and are not meant to be taken literally. Thus, the term "subjects" may refer to discrete patient groups but may be expanded to include research conducted on animals or specimens. Similarly, the "intervention" might not refer to a therapeutic procedure or drug, but to a diagnostic test or prognostic factor [6]. Other dimensions might be included (eg., restrictions on time, place, or clinical environments), but it is the explicit and unambiguous definition of each of the four basic dimensions that fulfils the requirements for specificity [7].

It is important to note that, although well-regarded as a useful means of formulating clinical queries, these ideas have only been tested recently. Booth and colleagues surveyed librarians' attitudes to the use of structured versus unstructured forms in a multicentre, before-after study involving six libraries [8]. They found that librarians were more likely to produce more complex search strategies and perform more precise searches when questions were received on the structured form.

As yet, there is limited published information to describe the current methods used by health care professionals in formulating questions, and much less is available to gauge their ability to frame focused clinical queries. The present study examined these issues in the setting of a clinical information and evidence evaluation service made available to health care professionals.

Methods

Objectives

The study sought to determine whether adding simple instructions and examples on clinical question formulation would increase the specificity of the question being submitted by the health care professional compared to using a standard form without instructions and examples.

Setting

The Centre for Clinical Effectiveness (CCE) opened at the Monash Medical Centre in Melbourne, Australia in March 1998 with the objective of enhancing patient outcomes through the clinical application of the best available evidence. The CCE is funded by the Southern Metropolitan Health Service (Southern Health) and the Acute Health Branch of the Victorian Department of Human Services. Among its many activities, the CCE operates an Evidence Centre that accepts clinical questions posed by members of Southern Health, identifies the best available evidence using a standardised protocol, provides a summary of the results, and assists staff in implementing the findings in clinical practice [9,10]. Requests for evidence originate from all sectors of Southern Health including the medical, nursing, and allied health services, healthcare administration, and other departments such as clinical engineering, infection control, and dietetics.

Questions from health care professionals within Southern Health are forwarded to the Evidence Centre using a standard form. Three levels of service are available, ranging from simple literature searches to systematic reviews of the literature around topical areas. Since its inception, the Evidence Centre has received about 700 requests for evidence evaluation, the particulars of which are maintained in an electronic database.

Eligibility

Eligible participants were first-time users of the services of the Evidence Centre. This was confirmed by checking that their names had not already been entered into the electronic database of all previous users of the Evidence Centre since its inception.

We did not enrol previous users of the service because staff of the Evidence Centre usually facilitate the refinement of clinical questions during consultation sessions and it was postulated that some learning effect would be present.

Interventions

In May 2000, as part of the Evidence Centre's regular marketing strategy, a mass mail-out of brochures was conducted to describe the evidence evaluation service and to invite questions of interest to be forwarded to the Evidence Centre. Each person received a promotional brochure and the standard form on which the Evidence Centre regularly receives requests (see Additional file 1). The standard form is primarily an open-ended self-administered questionnaire that begins by asking for the contact details of the person completing the form (name, position, department, etc.) for follow-up purposes. No effort was made to collect sociodemographic variables such as age, sex, or level of education as these were not routinely collected.

The next section consists of 10 questions eliciting specific information about the topic of interest. The focus of this study is the written response given by the participant to the first question: "The clinical question I would like answered:". This statement was isolated and entered into a database by an administrative officer who was not aware of the research question and who did not participate in any other phase of the study. The subsequent nine questions seek to clarify the purpose to which the evidence is to be used, the level of service required, the condition or context surrounding the query, the particular patients or clients of interest, the intervention or exposure and any comparison treatments or exposures, the relevant outcomes to be considered, the clinical environment, and any restrictions to be imposed on the search.

All requests submitted by eligible participants to the Evidence Centre from July 1, 2000 were prospectively analysed for completeness of each of the four basic dimensions of question specificity. Using a series of computer-generated random numbers, participants were assigned to one of two groups. The Control Group received the original form. The Intervention Group received a revised form (see Additional file 2) containing a brief explanation of the importance of proper question formulation, some written instructions, and a diagrammatic example of how dimensional elements may be arranged [4]. Both groups were invited to complete the forms and resubmit their requests, their participation being invaluable as part of a quality improvement exercise meeting the twin criteria of benefiting participants indirectly and posing no additional risks or benefits to participation [11]. On resubmission, the statement of interest was entered into the database. Thus, each participant potentially provided two entries: one at baseline (the original question) and another at follow-up (the re-formulated question).

Participants who failed to return their completed forms received a follow-up letter at one month. After two months of non-response, the participant was considered lost to follow-up.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the change in the proportion of reformulated questions that had each of the four dimensions of questions specificity explicitly described. Original and re-submitted versions of the questions were randomly ordered and sent to two outcome assessors who were unaware of group assignments. Both outcome assessors were previous Information Officers with at least one year's experience in evaluating clinical queries. Neither was involved in work with the Evidence Centre at the time of the study.

Each assessor was asked to rate the completeness of each of the four dimensions by determining if an explicit statement describing the particular dimension was present. The assessors were under strict instructions not to make assumptions about missing information.

Each assessor scored each dimension of the question pairs along a three-point ordinal scale (Table 1) using a standard form. We were primarily interested in the binary decision of whether a particular dimension was present or absent (i.e., a score of 1 or 2 versus 0) and whether the entire question had all four dimensions present. We defined a properly-specified question as a question having all four dimensions of question specificity present. Alternatively, a mis-specified question had at least one dimension absent.

Table 1.

Three-point ordinal scale used in determining the completeness of dimensional elements of question specificity during outcome assessment.

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | Present, broadly defined |

| 2 | Present, defined specifically |

Secondary outcomes included the differences in the degree by which a particular dimension was specified. If a particular outcome was present, outcome assessors were asked to rate it as being broadly described (a score of one) or specifically described (a score of two). Given the infeasibility of generating a decision rule that would apply to the multitude of topic areas, these decisions were subjective. All disagreements were resolved by a third assessor.

Sample size

We estimated the proportion of poorly formulated questions in the Control Group to be 80%. A study that randomised 23 participants to each arm would detect a 40% reduction in the proportion of poorly formulated questions with a power of 90% at the 5% level of significance. We made the a priori decision to stop recruitment when 30 participants were assigned to each of the groups or on July 2001 (one year after the first participant was recruited), whichever came first.

Randomisation

The randomisation schedule was generated using a pseudo-random number generator with a seed of 33 [12]. The randomisation schedule was maintained in electronic format and stored in a limited-access facility. It was accessed only twice during the project: once when project materials were being prepared and again during the analysis of results.

All project materials were placed in opaque envelopes and consecutively ordered according to the randomisation scheme. Forms for participants in the Intervention and Control Groups were indistinguishable by weight, colour, or size.

Blinding

Participants were partially blinded as to group assignment by not revealing specific details of the study and the project materials. Thus, we used statements that discussed broad issues (i.e., that the CCE was testing several forms to improve its services) when inviting participants. Blinding of outcome assessors was done by randomly ordering the statement-pairs they were to assess.

Statistical methods

Analyses were performed on Stata 7.0 [12] in a stepped manner. Preliminary data analysis included the generation of summaries and plots of each variable. Group differences in the primary outcome were examined using contingency tables and exact binomial procedures. Adjustment for baseline scores in the analysis of post-randomisation effects was modelled using logistic regression [13]. Differences in secondary outcomes were examined using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test given that the outcomes were paired and scaled in an ordinal fashion. Statistical significance was set a priori at a two-sided p-value of 0.05 or less.

Support for CONSORT

This article was prepared using the most recent version of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines [14], a copy of which is available at http://www.consort-statement.org/. The CONSORT guidelines recommend that a checklist be used to ensure that important items are not missed when reports are created. We include such a checklist (see Additional file 3).

Results

Participant flow

From July 1, 2000 to June 30, 2001, the Evidence Centre received a total of 276 requests for evidence evaluation. Of these, 52 (18.8%) were from new users of the service. All were invited to participate in the RCT and none refused.

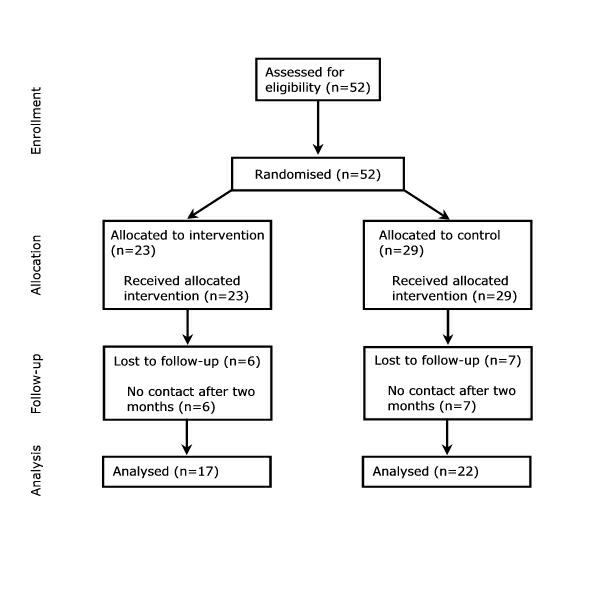

Figure 1 summarises the flow of participants through each stage of the trial. Twenty-three participants were assigned to the Intervention Group and 29 to the Control Group. All received the allocated intervention. Six participants in the Intervention Group (26.1%) and seven in the Control Group (24.1%) were lost to follow-up. Information from 17 Intervention Group and 22 Control Group participants were included in the final analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through each stage in the randomised controlled trial.

Participant characteristics

About 40% of participants were nurses, a third were medical doctors, and a quarter was affiliated with an allied health discipline (Table 2). Generally, the distribution of disciplines did not differ between participants and all users of the service. The only exception was in the allied health disciplines with a greater proportion overall participating in the trial (25.0% versus 14.0%; p = 0.034). There were no statistically significant between-group differences in the distribution of disciplines (Table 3; p = 0.743 by Fisher's exact test). Those lost to follow-up were no more likely to have come from a particular discipline as those who completed the study (Table 4; p = 0.603 by Fisher's exact test).

Table 2.

Distribution of the disciplines of participants enrolled into the RCT compared to all users of the Evidence Centre.*

| Discipline | Participants (n = 52) Frequency (%) | All Users (n = 550) Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing | 21 (40.4) | 223 (40.5) |

| Medicine | 17 (32.7) | 218 (39.6) |

| Allied Health† | 13 (25.0) | 77 (14.0) |

| Other‡ | 1 (1.9) | 32 (5.8) |

* Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding. † Includes such disciplines as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech pathology, pharmacy, etc. ‡ Includes requests from hospital administration, psychology, in-service education units, etc.

Table 3.

Distribution of disciplines according to group assignment.*

| Discipline | Intervention Group (n = 23) Frequency (%) | Control Group (n = 29) Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing | 8 (34.8) | 13 (44.8) |

| Medicine | 8 (34.8) | 9 (31.0) |

| Allied Health† | 6 (26.1) | 7 (24.1) |

| Other‡ | 1 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

* Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding. † Includes such disciplines as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech pathology, pharmacy, etc. ‡ Includes requests from hospital administration, psychology, in-service education units, etc.

Table 4.

Distribution of disciplines according to follow-up status.*

| Discipline | Participants completing the study (n = 39) Frequency (%) | Participants lost to follow-up (n = 13) Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing | 16 (41.0) | 5 (38.5) |

| Medicine | 11 (28.2) | 6 (46.2) |

| Allied Health† | 11 (28.2) | 2 (15.4) |

| Other‡ | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) |

* Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding. † Includes such disciplines as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech pathology, pharmacy, etc. ‡ Includes requests from hospital administration, psychology, in-service education units, etc.

Outcome assessment at baseline

Prior to adjudication by a third person, the overall agreement by two assessors was 90.0% with chance-corrected agreement (kappa statistic) at 68.6% (Standard Error [SE] = 16.0%; p < 0.001).

At baseline, approximately 20% of initially submitted questions in each of the groups was properly specified (an explicit statement describing each of the four dimensions of question specificity was present). There were no differences between the groups in the primary outcome at baseline (Table 5; 17.7% in the Intervention Group versus 22.7% in the Control Group).

Table 5.

Question specificity by group assignment at baseline and follow-up.*

| Specificity | Baseline Frequency (%) | Follow-up Frequency (%) | Within-Group Pre-Post Comparison (p-value)† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 17) | |||

| Primary Outcome‡ | 0.008 | ||

| Properly specified | 3 (17.7) | 10 (58.8) | |

| Mis-specified | 14 (82.4) | 7 (41.2) | |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||

| Patient | 0.028 | ||

| Absent | 5 (29.4) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Broad | 9 (52.9) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Specific | 3 (17.7) | 10 (58.8) | |

| Intervention | 0.157 | ||

| Absent | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Broad | 6 (35.3) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Specific | 11 (64.7) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Comparison | 0.014 | ||

| Absent | 11 (64.7) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Broad | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Specific | 6 (35.3) | 12 (70.6) | |

| Outcome | 0.008 | ||

| Absent | 3 (17.7) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Broad | 11 (64.7) | 7 (41.2) | |

| Specific | 3 (17.7) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Control Group (n = 22) | |||

| Primary Outcome‡ | -- | ||

| Properly specified | 5 (22.7) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Mis-specified | 17 (77.3) | 17 (77.3) | |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||

| Patient | 0.083 | ||

| Absent | 5 (22.7) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Broad | 12 (54.6) | 11 (50.0) | |

| Specific | 5 (22.7) | 7 (31.8) | |

| Intervention | 0.564 | ||

| Absent | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.6) | |

| Broad | 10 (45.5) | 11 (50.0) | |

| Specific | 10 (45.5) | 10 (45.5) | |

| Comparison | 0.974 | ||

| Absent | 16 (72.7) | 17 (77.3) | |

| Broad | 1 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Specific | 5 (22.7) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Outcome | 0.961 | ||

| Absent | 3 (13.6) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Broad | 13 (59.1) | 12 (54.6) | |

| Specific | 6 (27.3) | 6 (27.3) | |

* Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding. † Two-sided Wilcoxon signed ranks test. ‡ A properly specified question was one that had an explicit statement for each of the four dimensions of question specificity. If a question had at least one dimension coded as absent, it was classified as mis-specified.

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups when each of the four domains was examined individually. Patient or subject characteristics were present in some form in about 70.6% of questions in the Intervention Group and 77.3% of questions in the Control Group. The intervention was described in all of the questions submitted by the Intervention Group and in 20 of 22 questions by the Control Group (100.0% versus 90.1%).

A comparator for the intervention of interest was the dimension that was most often left unspecified. In the Intervention Group, 64.7% failed to state a comparison compared to 72.7% in the Control Group. The proportion of questions in which the outcome was stated did not differ between the groups: 82.4% for those assigned the intervention versus 86.4% for those assigned to control (p = 0.811).

Changes in question specificity at follow-up

Generally, favourable within-group changes were observed in the Intervention Group. Of the 14 questions previously rated as mis-specified in the Intervention Group, seven (50%) were assessed to have all four dimensions explicitly described at follow-up (Table 5). None of the questions that were previously rated as properly specified had their binary ratings changed. This reduction in the proportion of mis-specified questions was highly statistically significant (p = 0.008) and contrasts with the lack of any changes in the binary ratings in the Control Group. This finding was reflected in the similar lack of any significant post-randomisation changes in the ratings of all four dimensions of specificity. On the other hand, participants in the Intervention Group were statistically significantly more likely to explicitly describe patients (p = 0.028), comparisons (p = 0.014), and outcomes (p = 0.008) on follow-up.

Assessment of outcome could not proceed via logistic regression given that no changes were observed in the Control Group, causing specificity to be predicted completely by group assignment.

Discussion

This randomised controlled trial provides evidence to support the use of simple instructions to improve the formulation of questions used in the initial steps of evidence searching and critical appraisal. A large improvement in the proportion of properly specified questions was noted in participants who received these instructions, while no changes were apparent in those in which the instructions were withheld. When specific dimensions were compared longitudinally, participants who were given simple instructions were more likely to provide descriptions to three of the four dimensions under study.

The importance of the properly-formulated question as the consummate point from which some survey of a body of knowledge is launched is well-known as the research student's bane. The advantages of a focused research question often translates into a directed course of inquiry in which research "creep" is kept to a minimum.

The same might be said of questions that arise from a clinical encounter. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that the point of encounter between patient and physician is often a generous source of clinical queries [15,16]. However, while expert opinion espouses the need to apply the "best available evidence" to guide clinical decisions [6], the practical implementation of such advice is not often carried through [17-19]. For instance, Ely and co-workers [17] report that a sample of US family doctors failed to pursue up to 64% of their questions about patient care and those who did spent an average of two minutes seeking an answer. Any effort to improve the efficiency by which clinical queries are framed should provide valuable gains downstream.

Just what dimensions should be present? The model proposed by Counsell [4] nominates four standard dimensions. It is unclear whether each dimension should be weighted the same way in terms of importance to the total question. This study applied a uniform weighting structure, but others suggest that certain dimensions may be left out [20]. Indeed, it is our experience that useful information may be provided even if outcomes are vaguely or poorly specified. Moreover, Ely and co-workers [21] suggest that most clinical questions fall into a limited number of question types and propose that a taxonomy of sorts be applied. However, the validity and reliability of such schemata remain to be seen.

Given the broad professional base of the Centre's clientele, we could not rule out with specific certainty that some degree of between group "contamination" did not take place. This might be the case, for instance, if participants in the Control Group sought assistance from third parties with previous training in question formulation. Admittedly while such a situation would result in a diminution in the comparative differences both within and between groups, the magnitude of bias attributable to such an effect is unmeasured.

The setting of a broad professional base against which the study was conducted provides for another consideration that must be raised – that of assuming the information needs of a diverse group of health professionals are homogenous enough to warrant a single analysis. This problem speaks to the potential usefulness of targeted information assessment services for particular professional groups and is a viable research project that builds on these findings.

While the study showed that simple instructions improve question formulation for later use in an evidence-evaluation service, the present study was unable to determine the broader question of whether properly-specified clinical queries led to the provision of more useful evidence which resulted in better patient outcomes. Facets of this important research question are being examined in a series of projects called the Best Available Clinical Information (BACI) Studies (Elizabeth Burrows, Personal Communication, 2001).

Conclusions

This trial has demonstrated the positive impact of providing specific instructions on the proportion of properly-specified clinical queries. The evidence from this study has led to practical changes in the internal evidence-assessment procedures currently implemented. The evaluation of the long-term impact of such changes is an area of continued research.

Competing interests

None declared.

Description of additional files

Attachment 1.

File name: Attachment 1.pdf

File format: PDF

Title of data: "Standard form used for Evidence Centre requests. In this study, the this form was used by both groups during the pre-randomisation phase and by the Control Group post-randomisation."

Short description of data: Sample form used in data collection.

Attachment 2.

File name: Attachment 2.pdf

File format: PDF

Title of data: "Revised form used in this study. This form was used by the Intervention Group post-randomisation."

Short description of data: Sample form used in data collection.

Attachment 3.

File name: Attachment 3.doc

File format: Microsoft Word file

Title of data: "Checklist of items to include when reporting a randomised trial."

Short description of data: CONSORT checklist.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

"Standard form used for Evidence Centre requests. In this study, the this form was used by both groups during the pre-randomisation phase and by the Control Group post-randomisation."

"Revised form used in this study. This form was used by the Intervention Group post-randomisation."

"Checklist of items to include when reporting a randomised trial."

Contributor Information

Elmer V Villanueva, Email: Elmer.Villanueva@med.monash.edu.au.

Elizabeth A Burrows, Email: Elizabeth.Burrows@med.monash.edu.au.

Paul A Fennessy, Email: Paul.Fennessy@med.monash.edu.au.

Meera Rajendran, Email: Meera.Rajendran@hic.gov.au.

Jeremy N Anderson, Email: Jeremy.Anderson@med.monash.edu.au.

Acknowledgements

Ms Jane Predl provided invaluable administrative support.

References

- Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodare H, Smith R. The rights of patients in research. BMJ. 1995;310:1277–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6990.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. What clinical information do doctors need? BMJ. 1996;313:1062–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7064.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:380–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123:A12–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes R. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

- Richardson WS. Ask, and ye shall retrieve. Evidence-Based Medicine. 1998;3:100. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, O'Rourke AJ, Ford NJ. Structuring the pre-search reference interview: a useful technique for handling clinical questions. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000;88:239–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JN, Fennessy PA, Fennessy GA, Schattner RL, Burrows EA. "Picking winners": assessing new health technology. Med J Aust. 1999;171:557–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb123796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JN, Burrows EA, Fennessy PA, Shaw S. An 'evidence centre' in a general hospital: finding and evaluating the best available evidence for clinicians. Evidence-Based Medicine. 1999;4:102. [Google Scholar]

- Casarett D, Karlawish JH, Sugarman J. Determining when quality improvement initiatives should be considered research: proposed criteria and potential implications. JAMA. 2000;283:2275–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata 7.0. College Station, Texas, USA: Stata Corporation.

- Vickers AJ. The use of percentage change from baseline as an outcome in a controlled trial is statistically inefficient: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2001;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Helfand M. Information seeking in primary care: how physicians choose which clinical questions to pursue and which to leave unanswered. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:113–9. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covell DG, Uman GC, Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:596–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, Bergus GR, Levy BT, Chambliss ML, Evans ER. Analysis of questions asked by family doctors regarding patient care. BMJ. 1999;319:358–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7206.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl A, Smith H, White P, Field J. General practitioner's perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316:361–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein AR, Horwitz RI. Problems in the "evidence" of "evidence-based medicine". Am J Med. 1997;103:529–35. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambliss ML, Conley J. Answering clinical questions. J Fam Pract. 1996;43:140–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Gorman PN, Ebell MH, Chambliss ML, Pifer EA, Stavri PZ. A taxonomy of generic clinical questions: classification study. BMJ. 2000;321:429–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

"Standard form used for Evidence Centre requests. In this study, the this form was used by both groups during the pre-randomisation phase and by the Control Group post-randomisation."

"Revised form used in this study. This form was used by the Intervention Group post-randomisation."

"Checklist of items to include when reporting a randomised trial."