Abstract

Background: Social media (SoMe) platforms such as blogs, Twitter, and Facebook are increasingly becoming incorporated into education and scientific communities. In fields such as emergency medicine, clinicians have established communication channels through SoMe to engage in academic and clinical discussions for the purposes of professional growth. While the use of SoMe as an educational tool within the classroom has been previously described, its use as a professional tool has not been adequately investigated. Objective: To assess the perception of SoMe as an academic tool among deans of accredited health care professional schools in the United States. Methods: An electronic cross-sectional survey was distributed to deans of accredited medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools across the United States to assess the knowledge of SoMe, attitudes toward academic merit, and challenges to incorporating SoMe into scholarly activity. Responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Results: Of 188 responses (response rate = 22%), 162 (86%) agreed publication in a peer-reviewed journal ranked highest in academic merit, followed by publishing in medical Web sites (157, 84%), publication in a university-based newsletter (147, 78%), and personal medical education blog (150, 80%). Fifty-one (31%) of respondents stated that volume of viewership would improve academic merit, while 85 (52%) believed a peer-review process would improve academic merit. Conclusion: Although professional SoMe activities should not replace traditional publications, the result of this study suggest establishing a peer-review process to improve validity of such activities.

Keywords: Web 2.0, social media, scholarly activity

Background

The utilization of social media platforms, or Web 2.0, such as blogs, Twitter, and Facebook, are increasingly becoming incorporated into general daily activities and, more recently, into education and scientific communities.1-3 Various fields of education and academic science are employing social media as a vehicle to disseminate lecture material, the latest in research, new advancements, and exciting discoveries with the general public.4-9

Each social media platform serves a separate purpose within this model. Twitter serves as an amplification tool for research publications, blog articles, and local and national lectures and meetings for prospective audience members. Blogs, or Web-based logs or journals, provide a platform for clinicians to describe ongoing research, share and communicate information related to current and trending clinical topics with other pharmacists, and create an online footprint and presence. Importantly, utilizing social media platforms can be a tool to engage the younger generation of university students in general and can serve as a means to facilitate active learning of students in the health care professions in both the didactic and experiential settings.

In fields such as emergency medicine, physicians, nurses, and pharmacists alike are establishing communication channels through social media to engage in academic and clinical discussions for the purposes of professional growth.3,10 Despite the growth of the acceptance of social media publications, such as self-published podcasts or blogs, as a scholarly or professional activity, important critiques of the validity of the work provided through the use of these outlets have been posed.11 The educational, scientific, and clinical work provided by clinicians that has been incorporated and disseminated through the use of social media outlets such as Twitter, Facebook, personal blogs, or podcasts do not have the same rigorous peer-review process that scientific journals possess to ensure accuracy, relevance, and scientific merit of the content provided through these channels. Similarly, social media does not require verification of credentials of the authors before disseminating scientific opinion and likewise, readers providing review. Additionally, the stigma associated with the use of social media tools as purely personal vehicles may have led some to dismiss the use of this tool altogether.

While the use of social media as an educational tool within the pharmacy classroom has been previously described, its use as a professional tool to supplement traditional publication venues such as peer-reviewed journal articles has not been adequately investigated.12-15 Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the perception of social media as a valid professional academic tool from the perspective of the senior leadership of the academic community. We surveyed all deans of health care professional schools within the United States and accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC), and Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE).

Methods

This study and the survey tool were approved by the institutional review board of Rutgers University. An electronic cross-sectional survey was developed using the survey tool Qualtrics Research Suite software version 45,814 (Qualtrics Labs, Provo, UT). The survey was distributed via email hyperlink to the deans of accredited medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools across the United States. Email addresses of the deans were obtained from the respective Web sites of each of these health care professional schools. The survey was made available on June 7, 2013, and closed on July 15, 2013, with 3 reminder emails sent to nonresponders at 1-week intervals.

The survey tool consisted of 17 questions that assessed the general knowledge of social media, attitudes toward the academic merit of social media utilization (self-published podcasts or blogs) among clinicians, and obstacles to incorporating social media into medical education. Respondents were asked to provide demographic information with regard to the geographical region within the United States of America of the health care professional school surveyed, the number of full-time faculty at the school, average class size, and the number of years held as dean of the school. Responses were confidential and were filtered based on the type of health care professional school in which the dean served (medical, nursing, or pharmacy).

Survey results were electronically downloaded from Qualtrics and transferred to an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) for evaluation and analysis. Responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Of the 861 surveys sent to deans of accredited health care professional schools, 188 responses were received, yielding a response rate of 22%. Of the 188 deans who responded to the survey, 22 (12%) served as deans of medical schools, 128 (68%) served as deans of nursing schools, and 38 (20%) served as deans of pharmacy schools at the time the survey was conducted. Table 1 summarizes demographic data related to the health care professional schools and categorized by the type of school.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents.

| Type of Health Care Professional School |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All Schools, n (%) (N = 188) | Medical School, n (%) (n = 22) | Nursing School, n (%) (n = 128) | Pharmacy School, n (%) (n = 38) |

| Region | ||||

| Northeasta | 46 (24) | 6 (27) | 31 (24) | 9 (24) |

| Southeastb | 46 (24) | 7 (32) | 28 (22) | 11 (29) |

| Midwestc | 56 (30) | 3 (14) | 42 (33) | 11 (29) |

| Southwestd | 18 (10) | 3 (14) | 12 (9) | 3 (8) |

| Weste | 22 (12) | 3 (14) | 15 (12) | 4 (11) |

| Noncontinental United Statesf | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Average class size | ||||

| Less than 50 | 42 (22) | 0 (0) | 41 (32) | 1 (3) |

| 50 to 100 | 67 (36) | 6 (27) | 39 (30) | 22 (58) |

| 100 to 150 | 23 (12) | 6 (27) | 10 (8) | 7 (18) |

| 150 to 200 | 15 (8) | 7 (32) | 6 (5) | 2 (5) |

| 200 to 250 | 11 (6) | 2 (9) | 5 (4) | 4 (11) |

| 250 to 300 | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 1 (3) |

| More than 300 | 25 (14) | 1 (5) | 24 (19) | 1(3) |

| Years of school establishment | ||||

| Less than 25 years | 49 (26) | 3 (14) | 27 (21) | 19 (50) |

| 25 to 100 years | 106 (56) | 6 (27) | 93 (73) | 7 (18) |

| More than 100 years | 33 (18) | 13 (59) | 8 (6) | 12 (32) |

| Number of faculty | ||||

| Less than 25 | 76 (40) | 0 (0) | 73 (57) | 3 (8) |

| 25 to 50 | 50 (32) | 0 (0) | 33 (26) | 27 (71) |

| 50 to 75 | 18 (10) | 1 (5) | 13 (10) | 4 (11) |

| 75 to 100 | 9 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 4 (11) |

| 100 to 123 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 125 to 150 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| More than 150 | 23 (12) | 21 (95) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Years of serving as dean | ||||

| Less than 5 years | 98 (52) | 12 (55) | 67 (52) | 19 (50) |

| 5 to 10 years | 55 (29) | 4 (18) | 39 (30) | 12 (32) |

| 10 to 15 years | 18 (10) | 4 (18) | 12 (9) | 2 (5) |

| 15 to 20 years | 6 (3) | 1 (5) | 3 (2) | 2 (5) |

| 20 to 25 years | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| 25 to 30 years | 4 (2) | 1 (5) | 2 (2) | 1 (3) |

| More than 30 years | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 1 (3) |

Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Delaware, New York, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland.

Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Virginia, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Indiana, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and New Mexico.

California, Utah, Colorado, Nevada, Wyoming, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Washington.

Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

When asked about the use of social media outlets, 137 (73%) indicated the use of Facebook followed by 129 (69%) survey respondents indicating that they have a LinkedIn account. Other social media outlets indicated to be in use included Twitter (n = 51, 27%), Web-based log (“blog”) (n = 35, 19%), Google+ (n = 29, 15%), and Pinterest (n = 24, 13%). Fourteen (7%) indicated that they do not currently use social media.

Of those respondents who indicated the use of social media, when asked to approximate the ratio of social media used for personal versus professional purposes on a scale from 0 to 100, the mean percentage was determined to be 56.76% for personal use compared with 43.24% for professional use. Table 2 provides a reflection of the types of activities utilized by survey respondents with regards to social media.

Table 2.

Activities Conducted Through Social Media.

| Type of Health Care Professional School |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | All Schools, n (%) (N = 188) | Medical School, n (%) (n = 22) | Nursing School, n (%) (n = 128) | Pharmacy School, n (%) (n = 38) |

| How many hours per week do you spend on social media Web sites? | ||||

| Less than 1 hour | 87 (46) | 17 (77) | 53 (41) | 17 (45) |

| 1 to 2 hours | 55 (29) | 4 (18) | 39 (30) | 12 (32) |

| 3 to 5 hours | 30 (16) | 1 (5) | 22 (17) | 7 (18) |

| 6 to 8 hours | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 1 (3) |

| 8 to 10 hours | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 1 (3) |

| 10 to 15 hours | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| 15 to 20 hours | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| More than 20 hours | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1(1) | 0 (0) |

| How many times within the past month have you read an article on a medical blog? | ||||

| None | 68 (36) | 6 (27) | 45 (35) | 17 (45) |

| 1 to 3 | 87 (46) | 14 (64) | 58 (45) | 15 (39) |

| 4 to 6 | 22 (12) | 0 (0) | 18 (14) | 4 (11) |

| 6 to 10 | 7 (4) | 1 (5) | 5 (4) | 1 (3) |

| More than 10 | 4 (2) | 1 (5) | 2 (2) | 1 (3) |

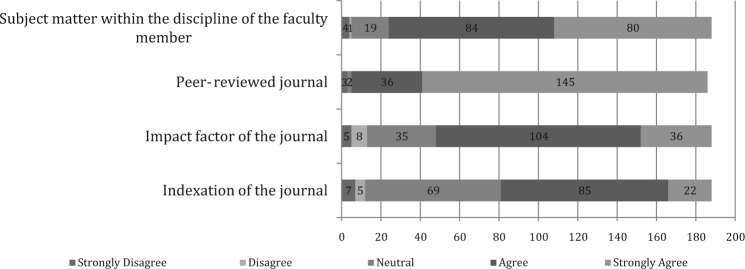

Figure 1 provides a reflection of the respondents’ views of factors determined to be important when considering a faculty member’s publication in a scientific journal (“1” meaning “strongly disagree” to “5” meaning “strongly agree”). A total of 145 (77%) indicated that they strongly agreed with the importance of publication within a peer-reviewed journal, and 80 (43%) strongly agreed that the subject matter of the publication should be within the discipline of the faculty member. A total of 104 (55%) indicated that they agreed that the impact factor of the journal was important, while 85 (45%) agreed that the indexation of the journal was an important factor to consider.

Figure 1.

Factors viewed to be important by deans for publications of faculty members in scientific journals (N = 188).

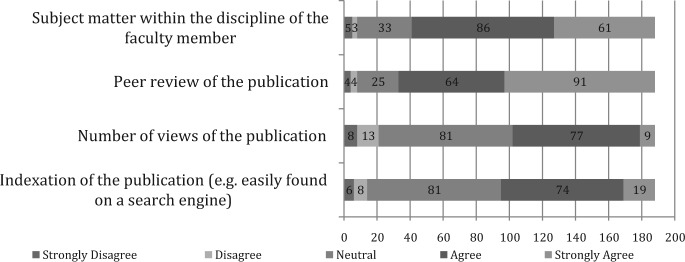

Figure 2 provides a reflection of the respondents’ views of factors determined to be important when considering a faculty member’s publication in a social media platform (“1” meaning “strongly disagree” to “5” meaning “strongly agree”). Ninety-one of the 188 respondents (48%) indicated that they strongly agreed with the importance of publication undergoing peer review, and 61 (32%) strongly agreed that the subject matter of the publication should be within the discipline of the faculty member. Seventy-seven (41%) indicated that they agreed that the number of views of the publication was important, while 74 (39%) agreed that the indexation of the publication on a search engine was an important factor to consider.

Figure 2.

Factors viewed to be important by deans for publications of faculty members in social media platforms (N = 188).

Respondents were asked to rank the academic merit of publications of faculty members published through a variety of mediums. The scale ranged from 1 to 4, with 1 meaning “most academic merit” to 5 meaning “least academic merit.” Publication in a peer-reviewed journal was deemed to have the most academic merit (n = 162, 86%), followed by publication on an online medical Web site, such as Medscape (n = 157, 84%) and publication in a newsletter section on a university-based Web site (n = 147, 78%), with publication on a personal medical education blog having the least academic merit (n = 150, 80%).

A total of 162 survey respondents (86%) ranked publication on a personal medical education blog as a “3” or “4” in academic merit, with 18 respondents being deans of medical schools, 109 being deans of nursing schools, and 35 being deans of pharmacy schools. For these respondents, 2 follow-up questions were asked, the first related to the number of views of the publication in 1 month, and the second related to peer review of the publication. Fifty-one (31%) of respondents felt that the volume of viewership would improve the academic merit, while 85 (52%) felt that a peer-review process would improve the academic merit (Table 3).

Table 3.

Follow-Up Questions Related to Publications on Personal Medical Education Blogs.

| Type of Health Care Professional School |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | All Schools, n (%) (N = 162) | Medical School, n (%) (n = 18) | Nursing School, n (%) (n = 109) | Pharmacy School, n (%) (n = 35) |

| The faculty member decides to post the review article on a personal medical education blog. The article receives 3000 views within the first month of posting on the blog. Would this change your views on academic merit? | ||||

| Yes | 51 (31) | 6 (33) | 36 (33) | 9 (26) |

| No | 111 (69) | 12 (67) | 73 (67) | 26 (74) |

| The faculty member decides to post the review article on a personal medical education blog. Prior to posting, the faculty member distributes the manuscript for peer review to contributors and/or authors of similar medical education blogs. Would this change your views on academic merit? | ||||

| Yes | 85 (52) | 11 (61) | 60 (55) | 14 (40) |

| No | 77 (48) | 7 (39) | 49 (45) | 21 (60) |

Respondents were asked to rank the academic merit of original research and/or presentations of faculty members through a number of channels. The scale ranged from 1 to 4, with 1 meaning “most academic merit” to 5 meaning “least academic merit.” Live platform presentations were deemed to have the most academic merit (148, 78%), followed by live poster symposiums (99, 52%) and Web-based video podcast presentation (83, 44%), with Web-based poster symposiums having the least academic merit (115, 61%).

Discussion

Social media platforms are an evolving tool used by academic health care professionals. These tools have been incorporated into didactic education models such as flipped classrooms and problem-based learning.1,5-8,14-19 Likewise, academic clinical health care professionals are increasingly using these media for intraprofessional communication and education. While this online evolution takes place, relevant discussion must take place to address factors such as the scholarly merit of social media self-publication activities, appropriate disclosure of conflicts of interest, and peer review.

The results of this survey study suggest that, while the professional use of social media platforms is recognized, there is still uncertainty regarding how it may or may not meet criteria for scholarly activity. However, defining scholarly activity for clinical faculty is critical toward establishing the academic value of such professional social media activities. The current definition of scholarly activity can be traced back to the Flexner report where clinical faculties were centered on a curriculum that focused on actively learning through clinical practice.20 Through this clinical practice, faculty could engage in original clinical research based on the patients they treat and clinical experience gained. Today, this model of clinical faculty is described as a 3-legged stool consisting of equal parts—teaching, clinical practice, and service.21 While blogging or other social media activities will never replace or substitute publication in peer-reviewed journals, there may still exist a place in which professional social media could exist within teaching and service. Teaching is fulfilled through creation and publication of blog posts of relevant clinical pearls or YouTube videos of the latest procedures and tricks of the trade, as well as iTunes Podcasts discussing and debating the most recent literature and evidence-based practice. Professional service is accomplished by “live tweeting” at major society conferences to reach audiences far beyond those present at the venue and promoting the profession among the health professional community at large.

As the professional use of social media continues to evolve, more activities linked to the traditional model become evident, for example, serving on editorial boards and reviewing abstracts for virtual meetings, such as the Social Media and Critical Care Conference (SMACC), or creating guidelines and policy as part of social media committees at academic institutions. As described in this survey, peer-reviewed publications ranked highly as a recognized form of scholarly activity. However, as the professional use of social media evolves, online movements such as Free Open Access Meducation, also known as FOAMed, groups are developing methods of establishing a peer-review process for blog publications, podcasts, and videocasts. As these methods continue to evolve, reassessing the place of social media use in the spectrum of scholarly activity is essential.

Social media publications by faculty members have begun to be taken into consideration as part of the promotion and tenure evaluation process at certain universities. A number of disciplines use social media for scholarly activity, including the fields of economics and humanities, as a means of sharing knowledge with the general public and providing opportunities for discussion and feedback of information provided through these mediums. These universities have incorporated publications in social media as some variation of the 3 components—clinical research, service, and teaching—necessary for promotion and tenure.22 While there is no literature describing the similarities or difference of promotion standards between allied health profession universities and colleges in the United States, in this study, they were considered to be similar. In addition, the Committee of Information Technology of the Modern Language Association Executive Council have put forth a set of guidelines23 as to how to consider such areas of work as scholarly activity due to the growing digital age, as new collaborations and areas of research that have come about in such an era. These guidelines provide a number of factors to consider when determining the validity of such scholarly work, which include relevance to the discipline of the faculty member, accessibility to such work by the general public, the level of involvement in which the faculty member is engaged in such activity, and qualified peer reviewers of the work put out through such forms of social media. The results of our survey demonstrate that these factors are indeed of value and significant to senior leaders of the academic community, regardless of whether the publication of the faculty member is in a scientific journal or social media platform, as illustrated in both Figures 1 and 2. This indeed is being recognized by a number of organizations, including Academic Coaching and Writing,24 which provides several resources and workshops designed to support and advance the writing of members of the academic community through a number of mediums that include both scientific journals and social media platforms.

While this survey study demonstrated meaningful attitudes, there are important limitations to acknowledge. First, the survey tool used was not validated and may not accurately assess the perception of social media as an academic tool within the academic community. However, as no such validated survey tool exists currently, this is an area for further development. Second, the limited response rate of this survey study (22%) does not meet the ideal response rate minimum of 80%, which adds complexity to the interpretation and analysis of these results,25 as it may not represent the views and attitudes of the entire academic community. However, it does provide important observations derived from the low response rate. The study population functioned as a census of all deans of accredited medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools across the United States rather than a sample of that group. Within this group, the sample of respondents may represent those who have knowledge of or participate in the scholarly use of social media. Conversely, those who did not respond may represent those with apprehensions regarding social media as a legitimate scholarly tool. Those apprehensions may be a reflection of a lack of knowledge of the current scholarly uses of social media or a reflection of the stigma associated with the personal use of social media. To appropriately incorporate social media use in academia, a complete and coordinated discussion is critical.

Despite these limitations, this survey revealed the current view of a portion of senior leaders of the academic community on the place of professional social media use in the scholarly activity spectrum. Moreover, this study is critical to heighten the awareness of the use of social media within a scholarly context, and to create discussion as to its place, in academia.

Conclusion

The scholarly merit of professional social media use is a growing debate critical to the evolution of academic publishing. While such professional social media activities should not replace traditional publications, the results of this study suggest that establishing a peer-review process may improve the validity of such activities. Further investigation and debate is vital to the continued development of professional social media use to ensure the greatest fulfillment of publication through emerging forms of media.

Appendix

Social Media in Academia Survey

- Please indicate your geographical region:

- Northeast (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Delaware, New York, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland)

- Southeast (Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Virginia, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia)

- Midwest (Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Indiana, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, Ohio, Wisconsin)

- Southwest (Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, New Mexico)

- West (California, Utah, Colorado, Nevada, Wyoming, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Washington)

- Noncontinental United States (Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico)

- Please indicate the accreditation body of your professional school:

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE)

- American Association of Colleges of Nurses (AACN)

- Please indicate the average class size at your professional school

- Less than 50 students

- 50 to 100 students

- 100 to 150 students

- 150 to 200 students

- 200 to 250 students

- 250 to 300 students

- Greater than 300 students

- Please indicate the number of years in which the professional school has been established

- Less than 25 years

- 25 to 100 years

- Greater than 100 years

- Please indicate the number of full-time faculty at your professional school

- Less than 25

- 25 to 50

- 50 to 75

- 75 to 100

- 100 to 125

- 125 to 150

- Greater than 150

- Please indicate the number of years of experience as Dean of the professional school

- Less than 5 years

- 5 to 10 years

- 10 to 15 years

- 15 to 20 years

- 20 to 25 years

- 25 to 30 years

- Greater than 30 years

- Please indicate which social media outlets you currently use (may select more than one):

- Twitter

- Facebook

- Pinterest

- Google Plus

- Instagram

- MySpace

- LinkedIn

- Web-based log (“blog”)

Provide a rough estimate of the percentage of social media outlets you use for personal versus professional use (must add up to 100%): Personal: _____ Professional: ______

Please indicate the number of hours you spend on social media websites per week

How many times within the past month have you read an article on a medical blog?

- What factors are important when considering a faculty members’ publication in a scientific journal?

- Indexation of the journal

- Impact factor of the journal

- Peer-review

- Subject matter within the faculty members’ field

- What factors are important when considering a faculty members’ publication on a social media platform?

- Indexation of the publication (can it be easily found on a Google search)

- Strongly agree → strongly disagree

- Number of views of the publication

- Peer-review

- Subject matter within the faculty members’ field

Please provide your response for the following scenarios:

Scenario 1: A faculty member at your school has a variety of teaching, clinical, and service activities that he or she is actively involved in. He or she drafts a review article on a clinical topic, and is considering submission to the following sources: peer-reviewed medical journal, online medical website (such as Medscape), a newsletter section on a university-affiliated website, or their own personal medical education blog. Please rank the activities in order of academic merit (1 meaning most through 4 meaning least):

___ Peer-reviewed medical journal

___ Online medical website (such as Medscape)

___ A newsletter section on a university-affiliated website

___ Personal medical education blog

Considering the above scenario, the faculty member decides to post the review article on the personal medical education blog. The article receives 3000 views within the first month of posting on the blog. Would this change your views on academic merit?

Yes

No

Considering the above scenario, the faculty member decides to post the review article on the personal medical education blog. Prior to posting, the faculty member distributes the manuscript for peer review to contributors and/or authors of similar medical education blogs. Would this change your views on academic merit?

Yes

No

Scenario 2: A faculty member at your school would like to submit original research for presentation at a professional meeting. The following channels are available for submission and presentation: live poster symposium, live platform presentation, web-based poster symposium, and web-based video podcast presentation. Please rank the activities in order of academic merit (1 meaning most through 4 meaning least):

___ Live poster symposium

___ Live platform presentation

___ Web-based poster symposium

___ Web-based video podcast presentation

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Sandars J, Schroter S. Web 2.0 technologies for undergraduate and postgraduate medical education: an online survey. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:759-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nielsen. State of the media: social media report Q3. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/reports/2011/social-media-report-q3.html. Published 2011. Accessed February 13, 2012.

- 3. Mansfield S, Morrison S, Stephens H, et al. Social media and the medical profession. Med J Aust. 2011;194:642-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giordano C, Giordano C. Health professions students’ use of social media. J Allied Health. 2011;40:78-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cain J, Fox B. Web 2.0 and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sircar F, Clauson K, Duffy M, Joseph S. Thematic analysis of pharmacy students’ perceptions of Web 2.0 tools and preferences for integration in educational delivery. Future Learning 2012;1:65-77. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vincent A, Weber Z. Using Facebook within a pharmacy elective course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75:13c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cain J, Policastri A. Using Facebook as an informal learning environment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McGowan B, Vartabedian B, Miller R, Wasko M. The “meaningful use” of social media by physicians. Paper presented at: 4th World Congress on Social Media and Web 20 in Medicine, Health, and Biomedical Research; September 17, 2011; Stanford University; http://www.medicine20congress.com/ocs/public/conferences/1/schedConfs/5/program.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lulic I, Kovic I. Analysis of emergency physicians’ Twitter accounts. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:371-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chatterjee P, Biswas T. Blogs and Twitter in medical publications: too unreliable to quote, or a change waiting to happen? S Afr Med J. 2011;101:712, 714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thompson L, Dawson K, Ferdig R, et al. The intersection of online social networking with medical professionalism. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:954-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cain J, Fink J. Legal and ethical issues regarding social media and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cain J. Online social networking issues within academia and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Estus E. Using Facebook within a geriatric pharmacotherapy course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pierce R, Fox J. Vodcasts and active-learning exercises in a “flipped classroom” model of a renal pharmacotherapy module. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prober CG, Heath C. Lecture halls without lectures—a proposal for medical education. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1657-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. White J, Kirwan P, Lai K, Walton J, Ross S. “Have you seen what is on Facebook?” The use of social networking software by healthcare professions students. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wipfli H, Press DJ, Kuhn V. Global health education: a pilot in trans-disciplinary, digital instruction. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York, NY: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilson MR. Scholarly activity redefined: balancing the three-legged stool. Ochsner J. 2006;6:12-14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gruzd A, Staves K, Wilk A. Promotion and tenure in the age of online social media. Proc Am Soc Info Sci Tech. 2011;48:1-9. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Modern Language Association. Guidelines for evaluating work in digital humanities and digital media. http://www.mla.org/resources/documents/rep_it/guidelines_evaluation_digital. Accessed December 11, 2013.

- 24. Academic Coaching and Writing, LLC. http://www.academiccoachingandwriting.org/. Accessed December 11, 2013.

- 25. Meszaros K, Barnett MJ, Lenth RV, Knapp KK. Pharmacy school survey standards revisited. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]