Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes and early complications of obese patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis via an anterolateral approach in the supine position (ALS-THA) and compare these outcome with of a matched control group of non-obese patients.

Patients and methods

Thirty-one hips in 28 patients with obesity (BMI ≧ 30 kg/m2) were included in this study. As a control group, 31 hips of 31 patients with a normal weight (BMI between 20 and 25 kg/m2) were matched based on age, sex, and laterality. Clinical evaluations using the Merle d’Aubigne and Postel hip score, radiological evaluations and perioperative complications were compared in two groups.

Results

There were no significant differences between the groups in the operative time, period of hospitalization, clinical hip score, or cup positioning, although the position of the cup tended to deviate from the optimal safe zone in the obese compared with non-obese group (32.3 and 16.1%, respectively). There was no infection, dislocation, nerve palsy, or life-threatening event in either group. The rate of avulsion fractures of the greater trochanter in the obese group was 3 times higher compared to that in the non-obese group.

Conclusions

As the clinical outcome of ALS-THA for the obese group is not inferior to that for the non-obese group, obesity is not considered to be a contraindication for ALS-THA. However, obesity increases the risk of intraoperative greater trochanteric fracture. Thus, surgeons should be particularly careful when manipulating the femur in this class of patients, who should be informed of this risk.

Keywords: Total hip arthroplasty, Anterolateral approach in supine position, Obesity, Greater trochanteric fracture

1. Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) via an anterolateral mini-incision approach has been reported to successfully reduce the rate of posterior dislocation and improve recovery and rehabilitation by preserving muscle insertions.1, 2

However, minimally invasive operative techniques demand that surgeons have experience and skill. Moreover, obesity further complicates the operation.

Obesity has been defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≧ 30 kg/m2 by the World Health Organization.3 BMI is calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the height in meters squared. Several studies have reported a relationship between obesity and poor outcomes after THA, including component malpositioning, infection, an increased operative time, longer hospitalization, and lower clinical scores.4, 5, 6, 7 Liu reported that obesity negatively influenced the dislocation rate, functional outcomes and operative time of primary THA.4 However, some studies have reported controversial results.8

Even in minimally invasive THA (MIS-THA), surgical indications for obese patients are controversial. For example, while Sculco stated that patients with BMI <28 kg/m2 were the most suitable for minimally invasive THA,9 other studies have reported that obesity is not a contraindication for the mini-incision approach.10, 11

As the population ages, the demand for THA to treat obese patients has been increasing in Japan. To the best of our knowledge, however, there are only a few reports on the early complications of THA performed via an anterolateral approach in the supine position (ALS-THA) in obese patients.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical and radiological results and complications during the intra- and early post-operative period of obese patients who underwent ALS-THA for osteoarthritis and compare them with those in a matched control group of non-obese patients.

2. Patients and methods

Between January 2010 and February 2015, a total of 756 primary cementless THAs were performed at our hospital. The data from all operations and clinical and radiological examinations were routinely collected and stored in our institutional database. From the original cohort, we included only patients with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis with no prior hip surgery. Patients with markedly dislocated hips were excluded because of the need for additional femoral shortening osteotomy. Other exclusion criteria included the following: a history of acute intracranial disease or hemorrhagic stroke, uncontrolled hypertension, myocardial infarction during the past 3 months, severe liver or renal disease, and pulmonary embolism. Patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THA, which was performed depending on cases in our hospital, were also excluded, leaving a remainder of 491 hips.

Of these 491 hips, 31 hips in 28 obese patients (BMI ≧ 30 kg/m2) were included in this retrospective, case-matched study.

The average age of the patients at the time of the operation was 62.6 years (range: 35–85 years). Seventeen hip replacements were performed on the right side, and 14 were performed on the left side. This study group included 6 men and 22 women.

As a control group, 31 hips (31 patients) of patients with a normal weight (BMI between 20 and 25 kg/m2) were selected from the 491 hips, after being matched based on age, sex, and laterality. The average BMI was 32.2 (range: 30.1–39.0) in the obese group and 22.0 (range: 20.0–24.6) in the matched non-obese group. The demographic data of the case-matched series are shown in Table 1. All patients were followed up for at least 6 months and had complete records, including radiographic and clinical examinations.

Table 1.

Preoperative patient date.

| Obese | Non-Obese | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side (Right: Left) | 17:14 | 17:14 | 1* |

| Sex (Male: Female) | 6:25 | 6:25 | 1* |

| Age (years old) | 62.6 (35–85) | 62.7 (46–81) | 0.76** |

| Height (cm) | 154.1 (130.0–183.0) | 157.0 (145.0–174.0) | 0.17** |

| Weight (kg) | 76.6 (53.0–104.0) | 54.6 (44.0–67.9) | <0.0001** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.2 (30.1–39.0) | 22.0 (20.0–24.6) | <0.0001** |

Data analysis.

Chi-squared test.

Mann-Whitney’s U test.

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study and all patients provided written informed consent.

2.1. Operation

All operations were performed under general anesthesia utilizing an anterolateral approach in the supine position; the interval between the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius muscles was opened using minimally invasive instruments, and the operations were conducted by or under the supervision of the senior author in a single institution.2, 12

Regarding the femoral component, a cementless, collarless, tapered, titanium fiber metal proximally coated stem (Versys Fiber Metal Taper/Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA) was used in all cases. The acetabular cup used in this study was the HA/TCP Trilogy Acetabular cup (Zimmer) in all cases. The optimal windows of abduction and anteversion angles of the acetabular cup were 30–50° and 5–25°, respectively. Bearing combinations included ceramic-on-polyethylene and cobalt chrome-on-polyethylene, and femoral heads were either 28 or 32 mm in size.

To reduce the need for allogeneic blood transfusion, preoperative autologous blood donation was used in all cases. Within 1 month of the operation, patients deposited one unit (400 mL) of blood and received it after the operation. In addition, all patients received 1000 mg of intravenous tranexamic acid just before surgical incision and just prior to wound closure.

Postoperatively, the patients underwent a standard rehabilitation protocol. They were mobilized with the assistance of physical therapy, and full weight-bearing was allowed with the use of a walker on the first postoperative day.

2.2. Evaluation items

As evaluation items, the operation time, estimated blood loss, requirement of allogenic transfusion, period of hospitalization and number of days to achieve gait with a cane were reviewed. Hemoglobin (Hb) concentrations (g/dL) within 1 month before the operation, within 1 h after the operation, and on postoperative day 1 were also recorded.

As clinical evaluation, pre- and post-operative pain and function were assessed using the Merle d’Aubigne and Postel hip score, which assigns up to 6 points for each category of pain, mobility, and the ability to walk, with a total of 18 points being given to a normal hip.13 The postoperative hip score was determined at the time of the latest follow-up.

Radiographic analysis was performed by digitizing anteroposterior (AP) pelvic and lateral radiographs. The images were evaluated by the same observer who was blinded to the patient group.

The preoperative femoral morphology was assessed by quantifying the Canal Flare Index (the ratio of the canal width of the femur at a point 20 mm proximal to the lesser trochanter to that at the isthmus) and classified into three general shapes: normal, stovepipe, and champagne-flute, according to Noble et al. in both groups.14

Postoperative radiographs were taken at each follow-up examination using a standardized technique. The immediate postoperative AP and lateral images were examined for cup abduction, anteversion, and stem orientation. Cup anteversion was measured on AP radiographs according to Widmer’s method.15 The numbers of cups within the so-called safe zone described by Lewinnek et al. were used as the anticipated target value of abduction at 40 ± 10° and anteversion at 15 ± 10° were measured in both groups.16

The incidence of implant loosening, the presence of a radiolucent line and stress shielding upon imaging were evaluated at the time of the most recent follow-up. The presence of radiolucent lines around the femoral stem was evaluated using the seven zones described by Gruen et al.17 Stress shielding was graded according to the classification of Engh et al.18

Peri- and post-operative complications including infection, dislocation, nerve palsy, life-threatening events, and re-operation, were recorded in both groups. Life-threatening events included venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular incidents.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed in both groups and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for quantitative parameters and the Chi-squared test for dichotomous parameters. The statistical software package StatView-J 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all calculations. Differences were considered significant when the p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

There was no significant difference in the mean age at the operation or height between the two groups (Table 1). The mean BMI was 32.2 and 22.0 in the obese and non-obese groups, respectively (P < 0.0001).

The mean operative time was slightly longer in the obese group compared with the non-obese group (70.8 and 64.8 min, respectively), but this difference was not significant (P = 0.25). The mean total blood loss was significantly greater in the obese group compared with the non-obese group (385.4 and 267.7 mL, respectively, P = 0.01), but no patient required allogenic transfusion after the operation in either group (Table 2). The Hb concentration was significantly higher in the obese group at all points of measurement except for postoperative day 1.

Table 2.

Perioperative variables in the two groups.

| Obese | Non-Obese | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (minutes) | 70.8 (42–110) | 64.8 (37–102) | 0.25 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 385.4 (100–850) | 267.7 (30–700) | 0.01 |

| Allogenic transfusion | 0 | 0 | |

| Hb | |||

| Preop. Hb (g/dL) | 13.9 | 13.1 | 0.03 |

| Immediately postop. (g/dL) | 12.2 | 11.3 | 0.01 |

| Postop. day 1 (g/dL) | 11.8 | 11.1 | 0.07 |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | 23.4 (13–48) | 21.3 (10–32) | 0.13 |

| Time to achieve gait with a cane (days) | 9.3 (6–27) | 7.6(4–18) | 0.008 |

Data analysis: Mann-Whitney’s U test.

The mean duration of the hospital stay was 23.4 days in the obese group and 21.3 days in the non-obese group. Patients in the obese group showed a slightly longer hospital stay compared with patients in the non-obese group, but this was not significant (P = 0.13). The mean number of days to achieve gait with a cane was significantly longer in the obese group compared with the non-obese group (9.3 and 7.6 days, respectively, P = 0.008).

Final follow-up evaluation was performed at an average of 3.1 years in the obese group and 3.3 years in the non-obese group.

The clinical results of the case-matched series are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in the hip scores between the two groups in any of the categories including the total either pre- or postoperatively.

Table 3.

Mean clinical results in the two groups (the Merle d’Aubigne and Postel hip score).

| Obese | Non-Obese | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperation | |||

| Pain | 1.71 (0–4) | 1.26 (0–3) | 0.28 |

| Mobility | 4.32 (2–6) | 4.32 (2–6) | 0.93 |

| Ability to walk | 2.68 (1–5) | 3.00 (1–6) | 0.65 |

| Total | 8.71 (4–13) | 8.58 (5–12) | 0.75 |

| Postoperation | |||

| Pain | 5.74 (5–6) | 5.87 (5–6) | 0.38 |

| Mobility | 5.84 (5–6) | 5.98 (5–6) | 0.38 |

| Ability to walk | 5.16 (3–6) | 5.35 (3–6) | 0.16 |

| Total | 16.74 (14–18) | 17.19 (14–18) | 0.097 |

Data analysis: Mann-Whitney’s U test.

The radiological results are shown in Table 4. Regarding the shape of the proximal femur, no significant difference was observed according to the Canal Flare index.

Table 4.

Radiographic results in the two groups.

| Obese | Non-Obese | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canal Flare Index (CFI) | |||

| Flare index | 3.9 (2.9–6.2) | 3.6 (2.6–6.3) | 0.08* |

| Stovepipe (<3.0) | 1 | 3 | |

| Normal (3–4.7) | 27 | 26 | |

| Champagne-flute (>4.7) | 3 | 2 | 0.88** |

| Cup component | |||

| Mean anteversion angle (°) | 18.0°(5.3–29.0) | 18.1°(3.4–39.8) | 0.71* |

| Mean abduction angle (°) | 37.0°(17.0–53.5) | 36.6°(20.7–64.3) | 0.60* |

| Incidence of migration | 0 | 0 | |

| Incidence of radiolucent line | 0 | 0 | |

| Femoral component | |||

| Varus alignment (≧3°) | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.50** |

| Valgus alignment (≧3°) | 0 | 0 | |

| Stem loosening | 0 | 0 | |

| Incidence of radiolucent line | |||

| Zone 1 | 10 (32.3%) | 8 (25.8%) | 0.78** |

| Zone 2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Zone 3 | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.5%) | 0.24** |

| Zone 4 | 10 (32.3%) | 10 (32.3%) | 1** |

| Zone 5 | 3 (9.7%) | 2 (6.5%) | 0.82** |

| Zone 6 | 1 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Zone 7 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Stress shielding | 0.98** | ||

| 0 | 13 (41.9%) | 12 (38.7%) | |

| 1 | 15 (48.4%) | 17 (54.8%) | |

| 2 | 3 (9.7%) | 2 (6.4%) | |

Data analysis:

Mann-Whitney’s U test.

Chi-squared test.

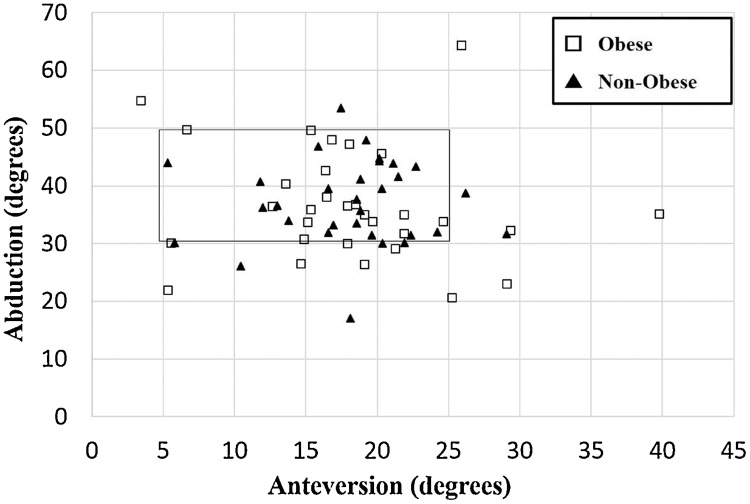

The mean cup abduction angle in the obese group was 37.0° (range: 17.0–53.5°), while the mean anteversion angle was 18.0° (range: 5.3–29.0°), compared with 36.6° abduction (range: 20.7–64.3°) and 18.1° anteversion (range: 3.4–39.8°) in the non-obese group. There was no significant difference in either the cup abduction or anteversion angle between the two groups (P = 0.60 and 0.71, respectively). Twenty-six (83.9%) cups in the non-obese group were within the safe zone, but only 21 (67.7%) cups in the obese group were within this zone (Fig. 1). However, this difference was not significant (P = 0.14).

Fig. 1.

A scatter plot showing the acetabular cup positioning of the two groups.

The safe zone window is included for reference.

Varus alignment of more than 3° was found in 2 (6.5%) hips in the obese group and 1 (3.2%) in the non-obese group (Table 4). The difference was also not significant (P = 0.50).

At the final follow-up, there was no acetabular migration or circumferential radiolucent line around the acetabular component.

The incidence and distribution of the radiolucent lines around the femoral stem are shown in Table 4. In both groups, radiolucent lines were seen mostly in zones 1 and 4.

Early complications of both groups are shown in Table 5. Avulsion fractures of the greater trochanter occurred in 3 patients (9.7%) during the operation in the obese group which was 3 times higher than that of the non-obese group (one patient, 3.2%). All cases were treated conservatively in both groups.

Table 5.

Complications documented in the two groups.

| Obese | Non-Obese | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avulsion fracture of greater trochanter | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (3.2%) | 0.31 |

| Crack of femoral calcar | 1 (3.2%) | 2 (6.5%) | 0.5 |

| Surgical site infection | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Dislocation | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Nerve palsy | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Life-threatening event | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Re-operation | 0 (0%) | 1* (3.2%) |

Data analysis: Chi-squared test.

A femoral neck fracture occurred due to stem subsidence, and re-operation was performed with wiring.

Intraoperative crack of the femoral calcar occurred in 1 patient in the obese group and 2 patients in the non-obese group. All such cases were successfully fixed with a circular wire intraoperatively.

In the non-obese group, more than 3 mm of subsidence of the femoral stem had occurred in 1 patient at 1 week after the operation, which led to a femoral neck fracture that necessitated re-operation with wiring (Table 5).

There was no infection, dislocation, nerve palsy, or life-threatening event in either group.

4. Discussion

The effect of obesity on THA outcomes has been the subject of considerable debate. Similarly, several reports have documented MIS-THA outcomes in obese patients.9, 10, 11, 19 Conversely, there have been few reports on the outcome of ALS-THA in obese patients, particularly in Japan. This may be because Asians are generally less obese compared with Western population. However, in Japan, where more than 50,000 THAs are performed annually, the number of obese patients requiring THA is expected to increase in the future. This is the first study to evaluate the outcomes of ALS-THA in obese patients in Japan, by matching them with non-obese patients.

The amount of operative blood loss was significantly larger in obese patients, but there was no case requiring allogenic blood transfusion after the operation. This suggests that we can perform ALS-THA safely, even in obese patients, with the use of autologous blood donation and intravenous tranexamic acid.

The average number of days required to achieve gait with a cane was significantly higher in the obese group, but according to the Merle d’Aubigne and Postel hip score, there was no significant difference between the groups in the ability to walk at the final follow-up. The period during which the obese group showed an inferior walking ability was short only in the post-operative period and improved with 3 years, at which time their walking ability was comparable to that in the non-obese group. Busato et al. reported that a high preoperative BMI is associated with poorer ambulation, and recommended weight loss prior to THA.19 In this study, however, obesity did not affect the clinical outcome of ALS-THA over the average 3-year follow-up.

The obese group in this study did not show any mean significant difference from the non-obese group when evaluating positioning for cup abduction, cup anteversion, positioning outside of the safe zone (30–45° abduction, 5–25° anteversion), or alignment of the femoral stem. However, the position of the cup tended to deviate from the safe zone in the obese group compared with the non-obese group. Elson reported that operating on a patient with a large BMI made it difficult to identify bony landmarks through the excess adipose tissue.20 Malpositioning of the acetabular component has been associated with a number of adverse clinical outcomes, including dislocation.21 For more precise cup positioning, an intraoperative roentgenogram or navigation may be useful. In this study, however, no dislocation occurred in either group during the follow-up. This may be because the ALS-THA approach, in which the posterior capsule and external rotators are spared, reduces the risk of dislocation.22 Our results indicated that ALS-THA for obese patients is advantageous compared to the posterior approach in terms of dislocation.

Meanwhile, there is a concern about the high number of femoral complications. Fractures of the proximal calcar were treated by cerclage wiring, and greater trochanter fractures required no internal fixation. They usually occur during elevation and rasping of the femur. Moreover, the incidence rate of greater trochanter fractures in the obese group was 3 times higher than that in the non-obese group, although the difference was also not significant (9.7% and 3.2%, respectively). Particularly among obese patients, elevating the femur is difficult because of the excessive amount of adipose tissue; thus, surgeons should be mindful to not to place an excessive load on the retractor when elevating the femur. The sufficient release of the capsule at the postero-superior neck remnant and fossa piriformis is important in elevating the femur gently and avoiding trochanteric fracture.

This study had a number of limitations. First, we studied date from a relatively small number of patients. We restricted the inclusion criteria to patients with only a diagnosis of osteoarthritis and no history of hip surgery, while we excluded those who had undergone simultaneous bilateral THAs. Thus, while the number of subjects was small, the influence of potentially confounding factors was limited. It is possible that there was no significant difference in the incidence of intraoperative greater trochanteric fractures between the two groups because of the small number of patients. For this reason, future studies that increase the number of cases are needed.

Second, this study employed a relatively short follow-up period. Further investigations are necessary to identify long-term complications in obese patients, such as the wear of components. Nevertheless, this study effectively documented the early complication of ALS-THA in obese patients. Moreover, we highlighted critical areas of concern that require caution among surgeons.

In conclusion, there was no difference in terms of patient outcomes regarding the operative time, period of hospitalization, clinical score or perioperative mortality between obese and matched non-obese patients. Obesity is not a contraindication for ALS-THA. However, avulsion fractures of the greater trochanter occurred at a rate that was 3 times higher in obese patients compared to non-obese patients. Thus, careful attention should be paid to avoid femoral fracture during femur manipulation in ALS-THA, particularly among obese patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

The retrospective use of patient date was approved by the ethics board of our hospital.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author contributions

Hirokazu Iwata conceived of the presented idea and planned and carried out the experiments. Kosuke Sakata, Eiji Sogo and Nanno Katsuhiko contributed to the interpretation of the results. Hirokazu Iwata wrote the manuscript in consultation with Sanae Kuroda and Tsuyoshi Nakai.

References

- 1.Bertin K.C., Röttinger H. Anterolateral mini-incision hip replacement surgery: a modified Watson-Jones approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:248–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pflüger G., Junk-Jantsch S., Schöll V. Minimally invasive total hip replacement via the anterolateral approach in the supine position. Int Orthop. 2007;31(1):7–11. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. (Accessed 28 August 2017).

- 4.Liu W., Wahafu T., Cheng M., Cheng T., Zhang Y., Zhang X. The influence of obesity on primary total hip arthroplasty outcomes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(3):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukada S., Wakui M. Decreased accuracy of acetabular cup placement for imageless navigation in obese patients. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(6):758–763. doi: 10.1007/s00776-010-1546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callanan M.C., Jarrett B., Bragdon C.R. The John Charnley Award: risk factors for cup malpositioning: quality improvement through a joint registry at a tertiary hospital. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(2):319–329. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1487-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murgatroyd S.E., Frampton C.M., Wright M.S. The effect of body mass index on outcome in total hip arthroplasty: early analysis from the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(10):1884–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michalka P.K., Khan R.J., Scaddan M.C., Haebich S., Chirodian N., Wimhurst J.A. The influence of obesity on early outcomes in primary hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2012;27:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sculco T.P. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2004;19(4):78–80. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wenz J.F., Gurkan I., Jibodh S.R. Mini-incision total hip arthroplasty: a comparative assessment of perioperative outcomes. Orthopedics. 2002;25(10):1031–1043. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20021001-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siguier T., Siguier M., Brumpt B. Mini-incision anterior approach does not increase dislocation rate: a study of 1037 total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;426:164–173. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000136651.21191.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakai T., Kakiuchi M. Minimally invasive anterolateral total hip arthroplasty on a standard operative table using a two-tined retractor and a double offset broach handle. J Orthop. 2009;6(3):e10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.d'Aubigne R.M., Postel M. Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36(3):451–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noble P.C., Box G.G., Kamaric E., Fink M.J., Alexander J.W., Tullos H.S. The effect of aging on the shape of the proximal femur. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;316:31–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widmer K.H. A simplified method to determine acetabular cup anteversion from plain radiographs. J Arthroplast. 2004;19(3):387–390. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewinnek G.E., Lewis J.L., Tarr R., Compere C.L., Zimmerman J.R. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(2):217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruen T.A., Mcneice G.M., Amstutz H.C. Modes of failure of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;141:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engh C.A., Bobyn J.D., Glassman A.H. Porous-coated hip replacement. The factors governing bone ingrowth: stress shielding, and clinical results. Bone Joint J. 1987;69(1):45–55. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B1.3818732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busato A., Röder C., Herren S., Eggli S. Influence of high BMI on functional outcome after total hip arthroplasty. Obes Surg. 2008;18(5):595–600. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elson L.C., Barr C.J., Chandran S.E., Hansen V.J., Malchau H., Kwon Y.M. Are morbidly obese patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty at an increased risk for component malpositioning? J Arthroplast. 2013;28(8):41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan M.A., Brakenbury P.H., Reynolds I.S. Dislocation following total hip replacement. Bone Joint J. 1981;63(2):214–218. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B2.7217144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dudda M., Gueleryuez A., Gautier E., Busato A., Röder C. Risk factors for early dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: a matched case-control study. J Orthop Surg. 2010;18(2):179–183. doi: 10.1177/230949901001800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]