Abstract

Clathrin mediated endocytosis is a fundamental transport pathway that depends on numerous protein-protein interactions. Testing the importance of the adaptor protein-clathrin interaction for coat formation and progression of endocytosis in vivo has been difficult due to experimental constrains. Here we addressed this question using the yeast clathrin adaptor Sla1, which is unique in showing a cargo endocytosis defect upon substitution of three amino acids in its clathrin-binding motif (sla1AAA) that disrupt clathrin binding. Live cell imaging showed an impaired Sla1-clathrin interaction causes reduced clathrin levels but increased Sla1 levels at endocytic sites. Moreover, the rate of Sla1 recruitment was reduced indicating proper dynamics of both clathrin and Sla1 depend on their interaction. sla1AAA cells showed a delay in progression through the various stages of endocytosis. The Arp2/3-dependent actin polymerization machinery was present for significantly longer time before actin polymerization ensued, revealing a link between coat formation and activation of actin polymerization. Ultimately, in sla1AAA cells a larger than normal actin network was formed, dramatically higher levels of various machinery proteins other than clathrin were recruited, and the membrane profile of endocytic invaginations was longer. Thus, the Sla1-clathrin interaction is important for coat formation, regulation of endocytic progression, and membrane bending.

Keywords: Endocytosis, clathrin, adaptor protein, yeast, endocytic machinery

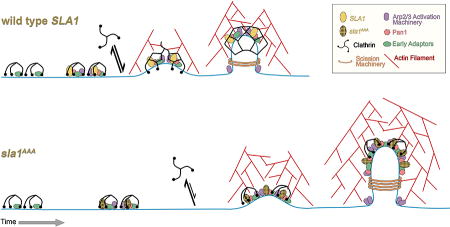

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Endocytosis is necessary for a variety of fundamental cellular activities, including nutrient internalization, regulation of signal transduction, and cell surface remodeling. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) is a major endocytic pathway involving numerous proteins that collect cargo into a membrane patch, invaginate the membrane, and pinch off a vesicle1–6. Quickly after being released, the vesicle loses the coat of clathrin and other machinery components and then fuses with endosomes. This process is conserved throughout evolution and proceeds through a well-defined sequence of events2,3,7–9.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been a very fruitful system to study CME using a combination of genetics, live-cell fluorescence microscopy, and biochemistry7,10–12. Several studies have revealed CME takes place through discrete stages and a well-choreographed assembly and disassembly pathway of endocytic machinery components. First, clathrin and other proteins, such as Ede1 and Syp1, arrive to the plasma membrane and begin collecting transmembrane cargo (e.g., receptors)10,11,13–16. This step is immobile, relatively long and variable in time (~ 1 min). Second, other fundamental components of the immobile phase arrive, including Sla1, Pan1 and Las17, approximately 20 sec before actin polymerization12. Third, a fast, mobile stage of endocytosis occurs concomitant with Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization17. Components of the coat, such as Sla1, move into the cell together with the bending membrane10,17,18. This mobile stage of endocytosis is brief (~15 sec) and culminates with vesicle scission, which is facilitated by the BAR-domain proteins Rvs161/167. Fourth, immediately after the scission step, most components of the coat disassemble and the released vesicle moves towards endosomes. While the various stages of endocytosis have been very well established, the regulation of the transition and progression through these stages is less well understood.

The clathrin ‘triskelion’, the soluble form of clathrin, is composed of three heavy chains and three light-chain subunits4,5,19–21. As clathrin is unable to bind directly to membrane components, coat assembly requires adaptors that link clathrin to membrane proteins and/or lipids22,23. The clathrin box (CB) is a type of clathrin-binding motif present in adaptor proteins that binds the N-terminal domain of the clathrin heavy chain19,24–26. In addition to assist in clathrin recruitment, adaptors also select and concentrate transmembrane protein cargo by binding to cytoplasmic sorting signals in cargo proteins27. Interestingly, binding to clathrin and cargo may also stabilize adaptors as part of the coat24,28. Additionally, adaptors interact with a host of accessory proteins that function in different stages of endocytosis. Sla1 binds clathrin through a variant clathrin box (vCB) sequence (LLDLQ) and also binds and collects transmembrane protein cargo containing the NPFxD endocytic signal29–33. Thus, Sla1 is a good example of an endocytic clathrin adaptor. Moreover, it was previously shown that mutation of the Sla1 vCB motif from LLDLQ to AAALQ in the SLA1 gene (sla1AAA) impedes physical interaction with clathrin and causes a defect in endocytosis of endogenous NPFxD-dependent cargo29. While this result underscored the importance of adaptor-clathrin interaction during CME, it is not clear if the endocytosis defect is the result of aberrant clathrin recruitment, Sla1 recruitment or both.

How does the adaptor-clathrin interaction impact progression of endocytosis and the ability of the CME machinery to bend the membrane and change the invagination shape? This question has gained particular relevance in light of recent findings that all the needed clathrin appears to be present at endocytic sites since early stages of CME when the membrane is still flat. This result was first reported in yeast cells, which necessitate actin polymerization to drive membrane bending and internalization17. Subsequently, the same correlative fluorescence and electron microcopy approach applied to mammalian cells, which may have a more nuanced actin requirement, also showed the presence of a full clathrin coat before membrane bending34,35. As a result, the traditional view of clathrin function in shaping the plasma membrane invagination has been challenged19,36,37. In this emerging new model, clathrin is being described as a passive player that adjusts to the changing curvature imposed by other components of the machinery such as actin and BAR-domain proteins17,34. It is therefore unclear if clathrin cooperates with such membrane shaping forces of the CME machinery during progression of endocytosis.

Here we explored the functional meaning of the adaptor-clathrin interaction using Sla1 vCB mutant cells (sla1AAA). We observed an overall decrease in clathrin recruitment and increase in Sla1 recruitment at CME sites, a significant delay in progression to later stages of endocytosis, an excess accumulation of the actin machinery and other CME proteins, and abnormal endocytic membrane profiles. The findings suggest that clathrin recruitment by adaptor protein contributes to transition to later stages of endocytosis and cooperates with other components of the CME machinery to shape the invaginating membrane.

RESULTS

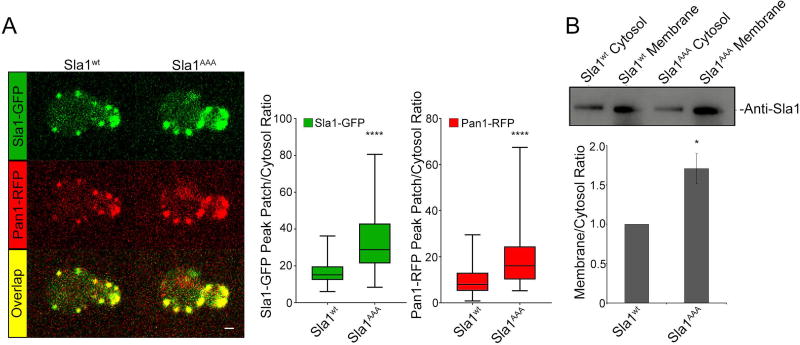

Impaired Sla1-Clathrin Binding Results in Higher Levels of Sla1 at Endocytic Sites

Our previous work showed sla1AAA cells constitute an ideal system to address the function of adaptor-clathrin interaction in CME29. First we wanted to establish if an impaired interaction between Sla1 and clathrin in sla1AAA cells could cause a defect in Sla1 recruitment, clathrin recruitment or both. To investigate this question, a strain expressing both Sla1AAA-GFP and Pan1-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus was generated and analyzed by two-color, live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy. A wild type control strain expressing Sla1-GFP and Pan1-RFP was also generated and analyzed in parallel. Pan1 is an endocytic protein with a recruitment time similar to that of Sla1 that serves as a reference for endocytic sites12,38,39. Importantly, Sla1AAA-GFP was present at all Pan1-RFP patches, paralleling results with wild type cells (Figure 1A). We then measured the Sla1 peak patch/cytosol fluorescent intensity ratio in both wild type and sla1AAA cells. Results from these experiments demonstrated that not only were levels of Sla1AAA-GFP not reduced at endocytic sites, but were actually enhanced to statistically significant higher levels relative to Sla1-GFP (Figure 1A). The number of Sla1AAA-GFP patches per cell was also increased relative to Sla1-GFP (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Interestingly, Pan1-RFP levels at endocytic sites were also enhanced in sla1AAA cells. As an independent method to assess Sla1AAA levels at the plasma membrane, we performed a biochemical experiment. Total membrane and cytosol fractions from yeast extracts expressing wild type Sla1 or the Sla1AAA mutant were separated by ultracentrifugation and subjected to immunoblotting analysis with anti-Sla1 antibodies (Figure 1B). Quantification of band intensities (Figure 1B) demonstrated higher membrane/cytosol ratio in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells, a result that correlates with the live cell fluorescent microscopy data. These results indicate that the defects in endocytosis observed in sla1AAA cells are not a result of reduced levels of Sla1AAA protein at endocytic sites.

Figure 1. Defective Sla1-clathrin binding results in higher levels of Sla1 and Pan1 at endocytic sites.

(A) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Sla1AAA-GFP and Pan1-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing Sla1wt-GFP and Pan1-RFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Left, panels show one representative frame of a movie (scale bar, 1µm). Right, quantification represented as box and whisker (minimum-maximum) plots showed higher peak patch/cytosol fluorescence intensity ratio for Sla1AAA-GFP relative to Sla1wt-GFP (P<0.0001, N=50 patches). The black horizontal line inside each box indicates the mean. Pan1-RFP levels at endocytic sites were also enhanced in cells expressing Sla1AAA-GFP relative to cells expressing Sla1wt-GFP (P<0.0001, N=50 patches). (B) Yeast cell extracts from sla1AAA cells and wild type cells were separated into membrane and cytosol fractions and subjected to immunoblotting analysis with anti-Sla1 antibodies. Representative experiment (top) and quantification (bottom) showing a higher proportion of membrane associated Sla1AAA relative to Sla1wt (P<0.05, N=6, bars represent mean ± SEM).

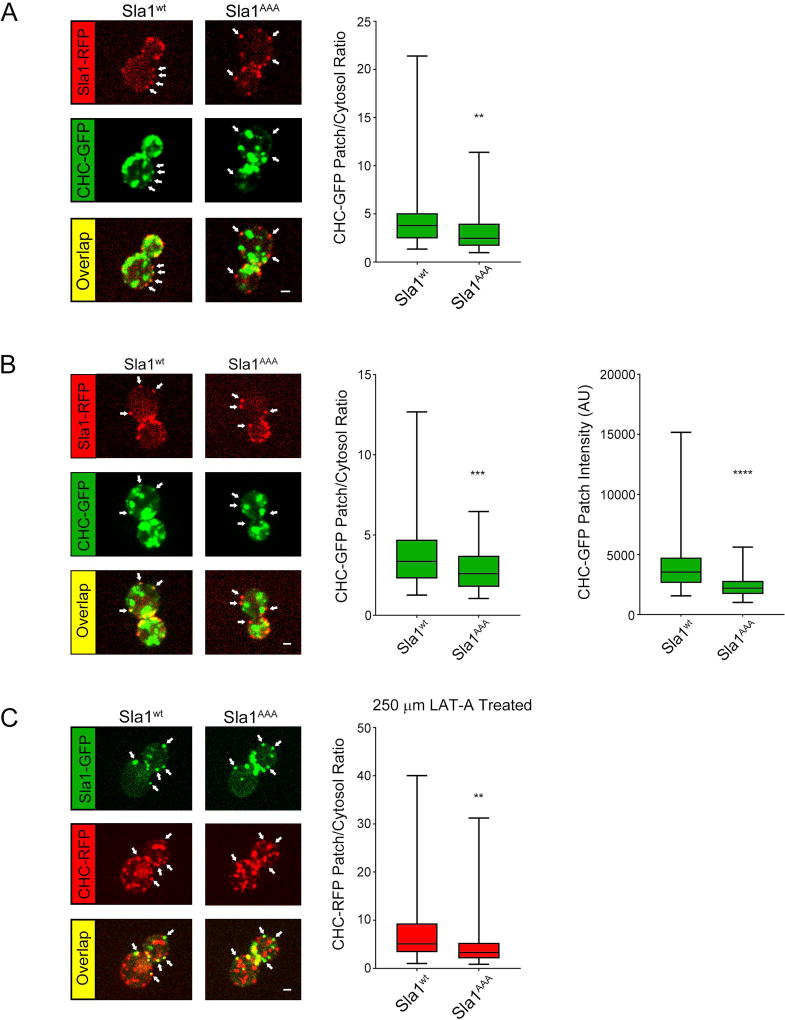

Deficient Sla1-Clathrin Binding Results in Lower Clathrin Levels During Late Stages of Endocytosis

In order to determine the effects of abolished Sla1-clathrin binding on clathrin levels at endocytic sites, we took a live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy approach. A strain expressing both Sla1AAA-RFP and clathrin heavy chain-GFP (CHC-GFP) from the corresponding endogenous locus was generated and analyzed. A wild type control strain expressing Sla1-RFP and CHC-GFP was also generated and analyzed in parallel. Since clathrin localizes to regions of the cell other than the plasma membrane (trans-Golgi Network, endosomes), Sla1-RFP was used as a marker for localization of clathrin to endocytic sites. Quantification showed lower levels of CHC-GFP at endocytic sites in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells (Figure 2A). To corroborate this result, comparison of CHC-GFP levels at endocytic sites between wild type and sla1AAA cells was also performed following a “blinded” approach in which the operator was unaware of the identity of the samples. Again, results demonstrated that reduced Sla1-clathrin binding causes lower absolute levels of CHC-GFP at endocytic sites as well as lower CHC-GFP patch/cytosol ratio (Figure 2B). To further examine clathrin levels at endocytic sites, we performed additional experiments in which we utilized both wild type and sla1AAA strains with switched tags (expressing Sla1 and CHC tagged with GFP and RFP respectively). The cells were treated with 250uM Latrunculin-A to inhibit actin polymerization, thus stalling the endocytic process at late stages and allowing for the accumulation of coat proteins at endocytic sites7,11. Confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis was performed to measure the levels of CHC-RFP at endocytic sites. Similar to the previous experiments, lower levels of CHC-RFP were found at endocytic sites in cells expressing the Sla1AAA mutant (Figure 2C). These results indicate that interaction with Sla1 is important for either recruiting clathrin and/or maintaining clathrin levels at endocytic sites. Given that in wild type cells initial clathrin recruitment precedes Sla1 arrival10,11, the Sla1-clathrin interaction is likely important for maintaining normal clathrin levels at later stages but not at early stages of endocytosis. Consistent with this idea, we measured CHC-GFP levels at endocytic sites before the arrival of Sla1-RFP and found no difference between wild type and sla1AAA cells, suggesting deficient Sla1-clathrin binding does not affect initial clathrin recruitment (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Reduced clathrin levels at endocytic sites during late phases of internalization explain the defects in endocytosis observed in sla1AAA cells.

Figure 2. Defective Sla1-clathrin binding results in lower clathrin levels during late stages of endocytosis.

(A) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Clathrin Heavy Chain (CHC)-GFP and Sla1AAA-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing CHC-GFP and Sla1wt-RFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Left, panels show one representative frame of a movie. Given that CHC-GFP also localizes to internal organelles, the presence of Sla1 was used as a reference to quantify CHC-GFP specifically at endocytic sites. White arrows indicate examples of endocytic sites. Scale bar, 1µm. Right, quantification represented as box and whisker (minimum-maximum) plots demonstrates lower levels of CHC-GFP at endocytic sites in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells (P<0.001, N=83 wild type cell patches and N=112 sla1AAA cell patches. (B) Similar CHC-GFP live cell imaging and quantification was performed in wild type and sla1AAA cells as described in Figure 2A. The quantification of this experiment was performed in a blind fashion such that the identity of the samples was not known by the investigator until post imaging and fluorescent intensity analysis. Left, panels show one representative frame of a movie with white arrows indicating examples of endocytic sites. Right, quantification showed lower CHC-GFP patch/cytosol fluorescence intensity ratio (P<0.001, N=75 patches per cell type) and patch fluorescence intensity (P<0.0001, N=75 patches per cell type) in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells. (C) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both CHC-RFP and Sla1AAA-GFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing CHC-RFP and Sla1wt-GFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Before imaging, cells were incubated for 20 min in media containing 250 µM Latrunculin A, an actin depolymerizing agent. Left, panels show one representative frame of a movie. Right, quantification demonstrates lower levels of CHC-RFP associated with endocytic sites (P<0.01, N=62 patches from wild type cells and N=64 patches from sla1AAA cells).

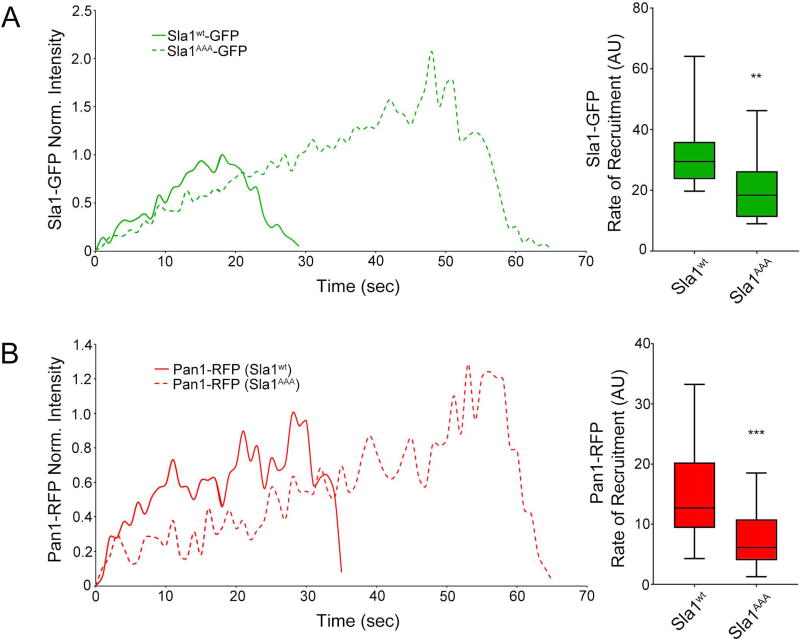

Defective Sla1-Clathrin Binding Slows the Rate and Delays the Timing of Sla1 and Pan1 Recruitment to Endocytic Sites

In order to further examine the effects of impaired Sla1-clathrin binding on Sla1 dynamics, we measured the rate of Sla1 recruitment in wild type and sla1AAA cells. Results from these experiments show that while peak endocytic site levels of Sla1AAA-GFP are much higher than Sla1-GFP, the rate of recruitment is lower for Sla1AAA-GFP (Figure 3A). This result along with lower levels of clathrin at endocytic sites in sla1AAA cells suggests that the Sla1-clathrin interaction is necessary for proper recruitment of both proteins.

Figure 3. Impaired Sla1-clathrin binding slows the rate of Sla1 and Pan1 recruitment to endocytic sites.

Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Sla1AAA-GFP and Pan1-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing Sla1wt-GFP and Pan1-RFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. (A) Left, representation of patch fluorescence intensity over time shows that Sla1AAA-GFP achieves a higher maximum value than Sla1wt-GFP, but takes significantly longer time. Right, box and whisker (minimum-maximum) plots showing the rate of Sla1AAA-GFP recruitment is significantly slower than Sla1wt-GFP (P<0.01, N=23 patches per cell type). (B) Left, representation of patch fluorescence intensity over time shows that Pan1-RFP also takes significantly longer time to reach its maximum recruitment in sla1AAA cells compared to wild type cells. Right, the rate of Pan1-RFP recruitment is significantly slower in sla1AAA cells (P<0.001, N=23 patches per cell type).

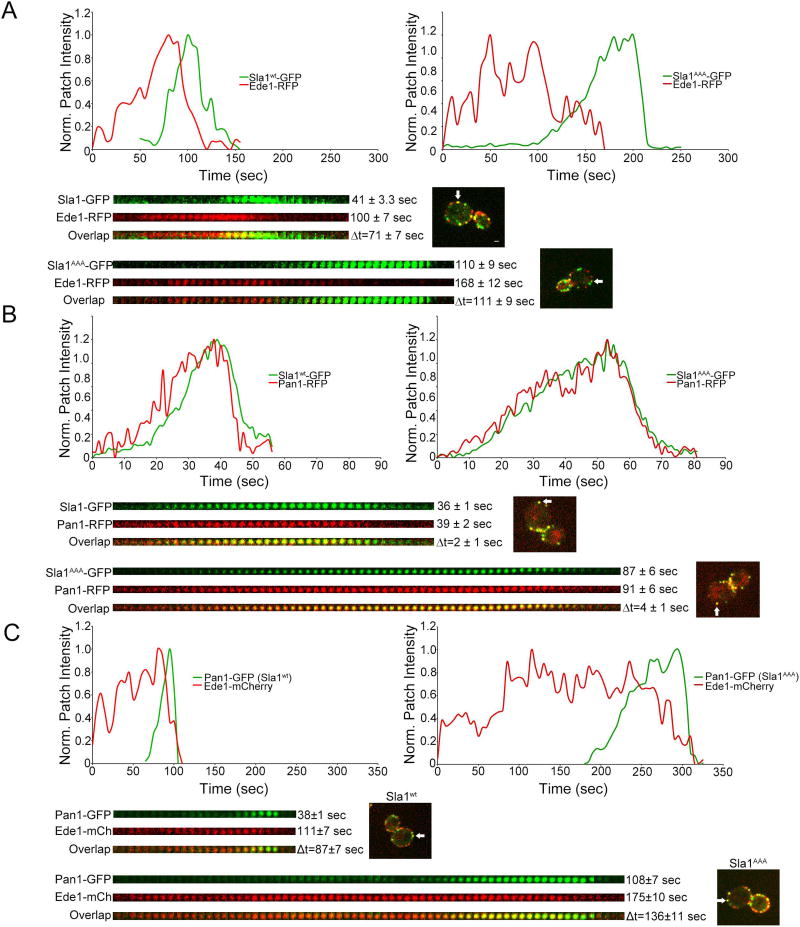

In order to determine if there was a delay in Sla1AAA-GFP recruitment compared with wild type Sla1-GFP, we generated strains expressing either of these proteins and Ede1-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus. Ede1 is an early marker that arrives at endocytic sites well before Sla113. Quantification of patch lifetimes and relative recruitment times between Ede1 and Sla1 gave two results of interest (Figure 4A). First, the timing of Sla1AAA-GFP recruitment following Ede1-RFP (Δt) was delayed compared with the Δt between wild type Sla1-GFP and Ede1-RFP (Δt = 111 ± 9 sec vs. Δt = 71 ± 7 sec). Second, the patch lifetime of Ede1-RFP was significantly extended in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells (168 ± 12 sec vs. 100 ± 7 sec). Together these results suggest that Sla1-clathrin binding is important for properly timed Sla1 recruitment to endocytic sites and progression of endocytosis.

Figure 4. Impaired Sla1-clathrin binding delays the timing of Sla1 and Pan1 recruitment to endocytic sites.

(A) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Sla1AAA-GFP and Ede1-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing Sla1wt-GFP and Ede1-RFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Graphs and kymographs demonstrate a delay in Sla1AAA-GFP recruitment following early arriving endocytic protein Ede1-RFP compared with Sla1wt-GFP. White arrows indicate the endocytic sites used to construct the graphs and kymographs. Average patch lifetimes and relative recruitment times are given next to each kymograph. The patch lifetime of both Sla1AAA-GFP and Ede1-RFP were longer than the corresponding times in wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=40 patches per strain). The timing of Sla1AAA-GFP recruitment following Ede1-RFP (Δt) was delayed compared with the control (P<0.001, N=40 patches per strain). Scale bar, 1µm. (B) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Sla1AAA-GFP and Pan1-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing Sla1wt-GFP and Pan1-RFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Graphs and kymographs demonstrate closely timed recruitment to endocytic sites of Pan1 with both Sla1AAA-GFP and Sla1wt-GFP. White arrows indicate the endocytic sites used to construct the graphs and kymographs. Average fluorescent patch lifetimes and relative recruitment times are given next to each kymograph. Quantification therefore showed the Δt was not significantly different between sla1AAA cells and wild type cells (P=0.26, N=31 patches per strain). The patch lifetime of both Sla1 and Pan1 was significantly longer in sla1AAA cells relative to control (P<0.0001, N=31 patches per strain). (C) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Pan1-GFP and Ede1-mCherry from the corresponding endogenous locus in both sla1AAA cells and wild type cells. Graphs and kymographs demonstrate a delay in Pan1-GFP recruitment following early arriving endocytic protein Ede1-mCherry in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells. White arrows indicate the endocytic sites used to construct the graphs and kymographs. Average patch lifetimes and relative recruitment times are given next to each kymograph. The patch lifetime of both Pan1-GFP and Ede1-mCherry were longer in sla1AAA cells than in wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=40 patches per strain). The timing of Pan1-GFP recruitment following Ede1-mCherry (Δt) was significantly delayed compared with the control (P<0.001, N=40 patches per strain).

Previous work showed Pan1 arrives at endocytic sites with similar timing as Sla1, and that the two proteins interact physically12,39. To begin assessing if the Sla1-clathrin interaction is important for the dynamics of other endocytic machinery proteins, we investigated the dynamics of Pan1 in sla1AAA cells. Just like Sla1, Pan1 also has a reduced rate of recruitment in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells (Figure 3B), despite achieving higher overall levels at endocytic sites (Figure 1A). The recruitment timing of Pan1 to endocytic sites is closely associated with that of Sla1 both in wild type and sla1AAA cells (Figure 4B), suggesting Pan1 recruitment should be delayed relative to Ede1 in sla1AAA cells. To corroborate this idea, we generated cells expressing Pan1-GFP and Ede1-mCherry from the corresponding endogenous locus both in wild type and sla1AAA background. Indeed the timing of Pan1-GFP recruitment following Ede1-mCherry (Δt) was delayed in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells (Δt = 136 ± 11 sec vs. Δt = 87 ± 7 sec) (Figure 4C). This result suggests a more general defect in coat formation and progression from early to late stages of endocytosis when the Sla1-clathrin interaction is impaired.

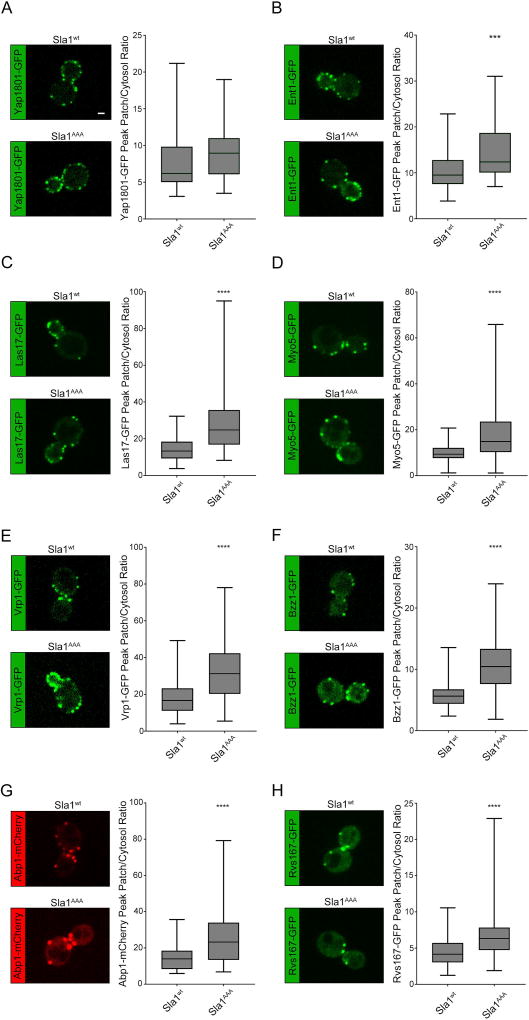

Other Endocytic Clathrin Binding Adaptors Are Present at Endocytic Sites in sla1AAA Cells

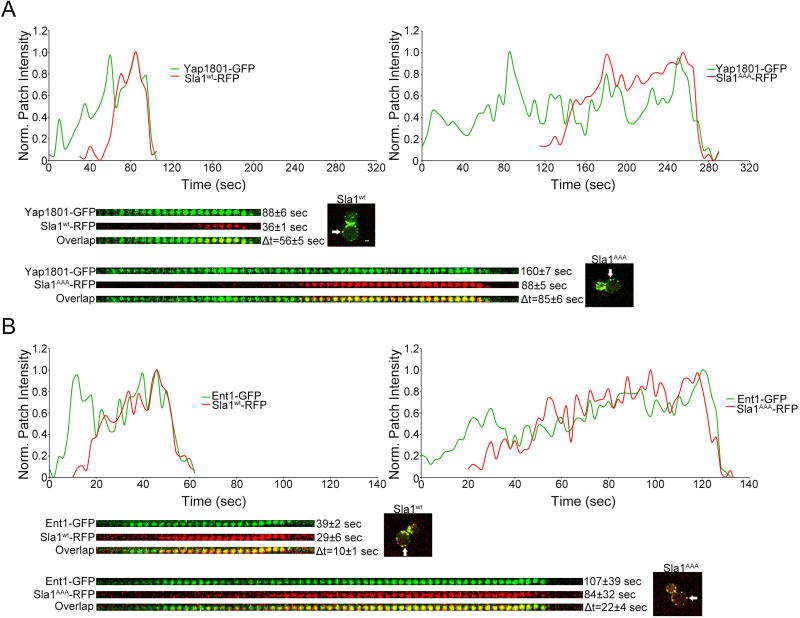

In addition to Sla1, the are other endocytic adaptors such as Yap1801/2 and Ent1/2 with the ability to bind clathrin26. Yap1801/2 and Ent1/2 have complementary/redundant functions, arrive to endocytic sites before Sla1, and remain until the patch internalizes40. To study their dynamics and overall recruitment levels, we generated cells expressing Yap1801-GFP and Sla1-RFP or Sla1AAA-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus. We also generated cells expressing Ent1-GFP and Sla1-RFP or Sla1AAA-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus. Quantification of patch lifetimes and relative recruitment times between Yap1801 and Sla1 gave two results of interest (Figure 5A). First, the timing of Sla1AAA-RFP recruitment following Yap1801-GFP (Δt) was delayed compared with the Δt between wild type Sla1-RFP and Yap1801-GFP (Δt = 85 ± 6 sec vs. Δt = 56 ± 5 sec). Second, the patch lifetime of Yap1801-GFP was significantly extended in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells (160 ± 7 sec vs. 88 ± 6 sec). Similar results were observed with Ent1-GFP. The Sla1AAA-RFP recruitment following Ent1-GFP (Δt) was delayed compared with the Δt between wild type Sla1-RFP and Ent1-GFP (Δt = 22 ± 4 sec vs. Δt = 10 ± 7 sec) (Figure 5B). Likewise, the patch lifetime of Ent1-GFP was significantly extended in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells (107 ± 39 sec vs. 39 ± 2 sec) (Figure 5B). Results with Yap1801 and Ent1 parallel those with Ede1 and Pan1, supporting the idea that Sla1-clathrin binding is needed for normal progression of endocytosis. Importantly, the fluorescence intensity of Yap1801-GFP and Ent1-GFP at endocytic sites was not decreased in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells. Yap1801-GFP fluorescence intensity was somewhat increased in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type, although the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 7A). The fluorescence intensity of Ent1-GFP was significantly increased in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells (Figure 7B). This result indicates that the clathrin binding function of Yap1801/Ent1 is not redundant with that of Sla1 and supports the idea that Sla1-clathrin binding is necessary for maintaining a proper level of clathrin during late stages of endocytosis.

Figure 5. Yap1801 and Ent1 display an extended lifetime at endocytic sites and a delayed Sla1 recruitment in cells with abolished Sla1-clathrin binding.

(A) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Sla1AAA-RFP and Yap1801-GFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing Sla1wt-RFP and Yap1801-GFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Graphs and kymographs demonstrate a delay in Sla1AAA-RFP recruitment following Yap1801-GFP compared with Sla1wt-GFP. White arrows indicate the endocytic sites used to construct the graphs and kymographs. Scale bar, 1µm. Average patch lifetimes and relative recruitment times are given next to each kymograph. The patch lifetime of both Yap1801-GFP and Sla1AAA-RFP were longer than the corresponding times in wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=40 patches per strain). The timing of Sla1AAA-RFP recruitment following Yap1801-GFP (Δt) was delayed compared with the control (P<0.001, N=40 patches per strain). (B) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Sla1AAA-RFP and Ent1-GFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing Sla1wt-RFP and Ent1-GFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Graphs and kymographs demonstrate a delay in Sla1AAA-RFP recruitment following Ent1-GFP compared with Sla1wt-GFP. White arrows indicate the endocytic sites used to construct the graphs and kymographs. Average patch lifetimes and relative recruitment times are given next to each kymograph. The patch lifetime of both Ent1-GFP and Sla1AAA-RFP were longer than the corresponding times in wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=35 patches per strain). Also, the timing of Sla1AAA-RFP recruitment following Ent1-GFP (Δt) was delayed compared with control (P<0.01, N=35 patches for the wild type cells and N=31 patches for sla1AAA cells).

Figure 7. Deficient Sla1-Clathrin binding results in higher levels of coat proteins, polymerized actin, the actin polymerization machinery and the scission machinery.

Live cell confocal fluorescent microscopy analysis of various endocytic proteins expressed from the corresponding endogenous locus both in wild type and sla1AAA cells. Scale bar, 1µm. The peak patch/cytosol fluorescence intensity ratio was determined for each protein in both sla1AAA cells and control cells and is represented using box and whisker plots: (A) Yap1801-GFP (N=40 patches per strain); (B) Ent1-GFP (N=35 patches per strain); (C) Las17-GFP (N=50 patches per strain); (D) Myo5-GFP (N=70 patches per strain); (E) Vrp1-GFP (N=50 patches per strain); (F) Bzz1-GFP (N=50 patches per strain); (G) Abp1-mCherry (N=50 patches per strain); (H) Rvs167-GFP (N=70 patches for wild type cells and N=64 patches sla1AAA cells). With the exception of Yap1801, the peak patch/cytosol fluorescence intensity ratio was significantly higher for each of these proteins in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells (P<0.001 for Ent1-GFP and P<0.0001 in all other cases).

Sla1-Clathrin Binding is Necessary for Normal Progression Between Coat Formation and Actin Polymerization

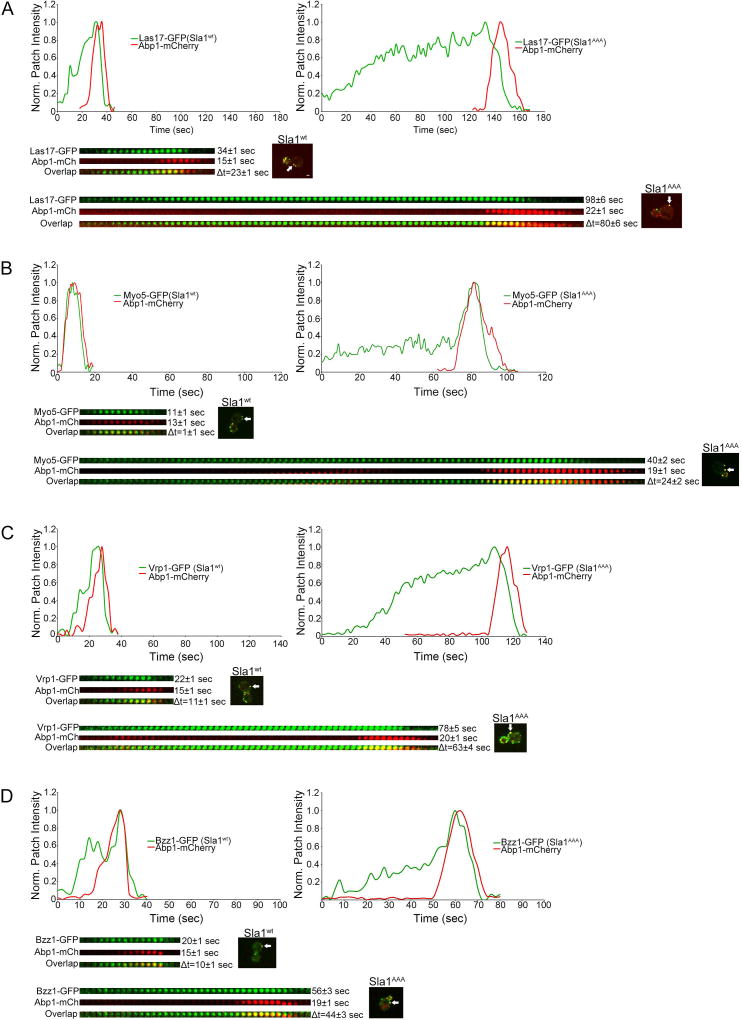

Recruitment of Sla1 to endocytic sites is one of the final steps in coat formation. Shortly after Sla1 recruitment (~15 sec), Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization takes place, which is typically detected in live cells by imaging Abp17. Las17 and Myo3/5 are the strongest activators of Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization12. In wild type cells, Las17 arrives to endocytic sites at the same time as Sla1 and Myo3/5 arrive simultaneously with Abp112,41. Vrp1 and Bzz1 are also part of the actin polymerization machinery and in wild type cells they arrive at endocytic sites just before Abp1 (~5 sec)12,42. Here we examined the dynamics of Las17-GFP, Myo5-GFP, Vrp1-GFP and Bzz1-GFP relative to Abp1-mCherry in cells expressing each protein pair from the corresponding endogenous locus, both in wild type and sla1AAA background. In these experiments it was determined that the patch lifetime of all of these four proteins was significantly extended in sla1AAA cells beyond that found in wild type cells (Figure 6). Importantly, the time between their recruitment and Abp1-mCherry arrival (Δt) was significantly increased in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells (Δt = 80 ± 6 sec vs. Δt = 23 ± 1 sec for Las17-GFP; Δt = 24 ± 2 sec vs. Δt = 1 ± 1 sec for Myo5-GFP; Δt = 63 ± 4 sec vs. Δt = 11 ± 1 sec for Vrp1-GFP; Δt = 44 ± 3 sec vs. Δt = 10 ± 1 sec for Bzz1-GFP). Furthermore, the maximal level of these four proteins at endocytic sites was also increased in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells (Figure 7C–F), as was the case with Sla1, Pan1 and Ent-1 (Figure 1 and 7B). These results demonstrate that deficient Sla1-clathrin binding results in delayed actin polymerization, as marked by Abp1-mCherry, relative to the recruitment of the actin polymerizing machinery. Given that clathrin is present at reduced levels in sla1AAA cells (Figure 2), the data suggests a link between formation of the endocytic clathrin coat and initiation of actin polymerization, one of the final stages in CME.

Figure 6. Normal transition between coat formation and actin polymerization depends on Sla1-clathrin binding.

(A) Graphs and kymographs obtained by confocal fluorescent microscopy analysis of Las17-GFP and Abp1-mCherry expressed from the corresponding endogenous locus in wild type and sla1AAA cells. White arrows indicate the endocytic sites used to generate the graphs and kymographs. The patch lifetime of both Las17-GFP and Abp1-mCherry were longer in sla1AAA cells than in wild type cells (P<0.0001 for both proteins, N=50 patches per strain). The timing of Abp1-mCherry recruitment following Las17-GFP (Δt) was delayed in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=50 patches per strain). Scale bar, 1µm. (B) Graphs and kymographs obtained by confocal fluorescent microscopy analysis of Myo5-GFP and Abp1-mCherry expressed from the corresponding endogenous locus in wild type and sla1AAA cells. The patch lifetime of both Myo5-GFP and Abp1-mCherry were longer in sla1AAA cells than in wild type cells (P<0.0001 for both proteins, N=70 patches per strain). The timing of Abp1-mCherry recruitment following Myo5-GFP (Δt) was delayed in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=70 patches per strain). Also notice that in sla1AAA cells the Myo5-GFP fluorescence intensity is present for a long time before Abp1-mCherry arrival but increases concomitantly with Abp1-mCherry recruitment (C) Graphs and kymographs obtained by confocal fluorescent microscopy analysis of Vrp1-GFP and Abp1-mCherry expressed from the corresponding endogenous locus in wild type and sla1AAA cells. The patch lifetime of both Vrp1-GFP and Abp1-mCherry were longer in sla1AAA cells than in wild type cells (P<0.0001 for both proteins, N=50 patches per strain). The timing of Abp1-mCherry recruitment following Vrp1-GFP (Δt) was delayed in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=50 patches per strain). (D) Graphs and kymographs obtained by confocal fluorescent microscopy analysis of Bzz1-GFP and Abp1-mCherry expressed from the corresponding endogenous locus in wild type and sla1AAA cells. The patch lifetime of both Bzz1-GFP and Abp1-mCherry were longer in sla1AAA cells than in wild type cells (P<0.0001 for Bzz1-GFP and P<0.05 for Abp1-mCherry, N=30 patches per strain). The timing of Abp1-mCherry recruitment following Bzz1-GFP (Δt) was delayed in sla1AAA cells compared with wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=50 patches per strain).

Impaired Sla1-Clathrin Binding Results in Higher Levels of Polymerized Actin and Scission Machinery

In our analysis of the actin machinery we noticed that in sla1AAA cells the Abp1-mCherry patches appeared to be much brighter and the lifetime of Abp1-mCherry was longer compared to wild type cells. Since actin polymerization is considered the main force-generating component of CME and Abp1 acts as a marker for polymerized actin, it was important to corroborate these observations. Quantification showed that indeed in sla1AAA cells the Abp1-mCherry levels were significantly higher (Figure 7G) and the patch lifetime was slightly longer (~5 sec, Figure 6) compared with wild type cells. This data indicates defective Sla1-clathrin binding results in a larger network of polymerized actin at endocytic sites.

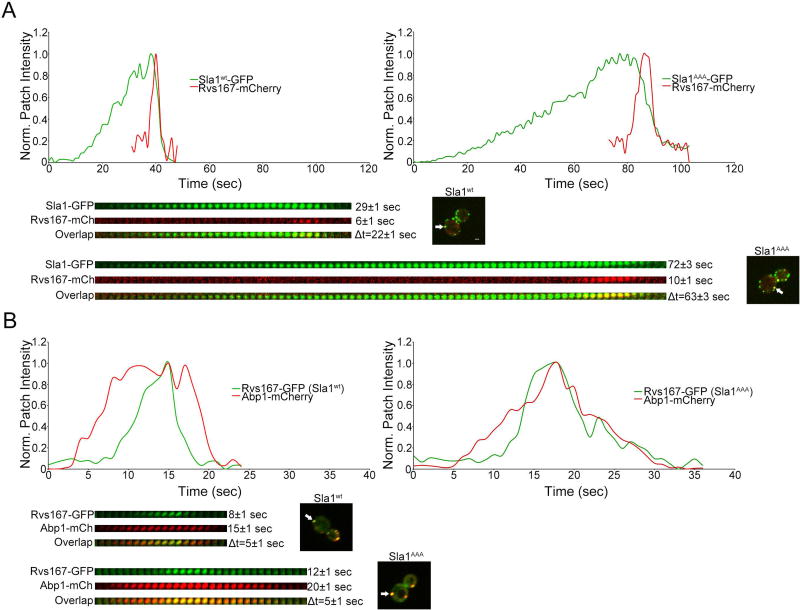

We then investigated the effects of impaired Sla1-clathrin interaction on the scission machinery. Rvs167 is one of two BAR domain-containing scission proteins recruited to the endocytic site neck right after actin polymerization begins to assist in vesicle release10,43. We generated and examined cells expressing Rvs167-mCherry and Sla1-GFP or Sla1AAA-GFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (Figure 8A). Rvs167-mCherry was significantly delayed in its recruitment following Sla1AAA-GFP compared with wild type Sla1-GFP (Figure 8A). This result parallels the late recruitment of Abp1-mCherry in sla1AAA cells (Figure 6). Also, similar to Abp1-mCherry, Rvs167-GFP fluorescent intensity appeared to be higher and patch lifetime longer in sla1AAA cells relative to wild type cells. We thus generated and analyzed wild type and sla1AAA strains expressing Rvs167-GFP and Abp1-mCherry from the corresponding endogenous locus. Quantification showed that indeed in sla1AAA cells the maximal levels of Rvs167-GFP were significantly higher (Figure 7H) and the patch lifetime of Rvs167-GFP was extended by ~5sec (Figure 8B) when compared to wild type cells. Rvs167-GFP recruitment occurs shortly after Abp1-mCherry both in sla1AAA and wild type cell (Figure 8B). This data indicates defective Sla1-clathrin binding results in the recruitment of more molecules of Rvs167 to endocytic sites with a timing closely associated with actin polymerization.

Figure 8. Normal transition between coat formation and recruitment of the scission machinery depends on Sla1-clathrin binding.

(A) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both Sla1AAA-GFP and Rvs167-mCherry from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing Sla1wt-GFP and Rvs167-mCherry were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Graphs and kymographs are depicted and average patch lifetimes and relative recruitment times are given next to each kymograph. Quantification demonstrates a significant delay in Rvs167-mCherry recruitment following Sla1AAA-GFP compared with control cells (P<0.0001, N=70 patches per strain). The patch lifetime of Rvs167-mCherry was longer in sla1AAA cells than in wild type cells (P<0.0001, N=70 patches per strain). Scale bar, 1µm. (B) Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing Rvs167-GFP and Abp1-mCherry from the corresponding endogenous locus in both sla1AAA cells and control cells. Analysis confirmed both proteins have an extended patch lifetime in sla1AAA cells relative to control cells (P<0.0001, N=50 patches per strain). The recruitment timing of Rvs167-GFP following Abp1-mCherry in sla1AAA cells was the same as in wild type cells (Δt=5±1 sec in both strains, N= 50 patches per strain).

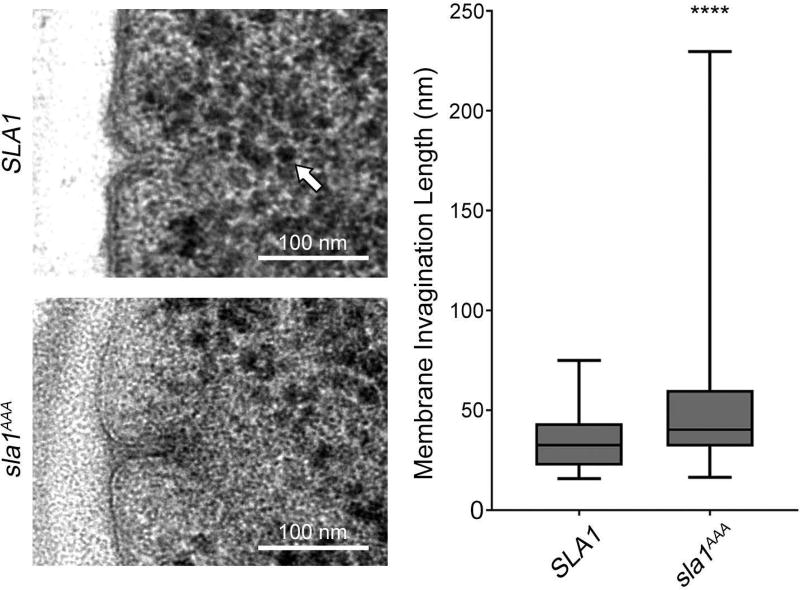

Defective Sla1-clathrin Binding Enhances Average Membrane Invagination Length and the Size of the Ribosome Exclusion Zone

To analyze the effect of impaired Sla1-clathrin binding in endocytic membrane invagination shape with appropriate resolution, wild type and sla1AAA cells were subjected to high pressure freezing and processed for thin-section electron microscopy. Both the endocytic membrane invagination and its surrounding ribosome exclusion zone, which is caused mainly by the endocytic coat and the actin network17, appeared to be abnormally large in sla1AAA cells. Quantitative analysis corroborated the average invagination length was longer in sla1AAA cells compared to control cells (Figure 9). This result indicates that the Sla1-clathrin interaction contributes to proper shaping of the endocytic invagination likely through either recruitment or stabilization of the clathrin coat. Furthermore, the ribosome exclusion zone was quantified in wild type and sla1AAA cells by measuring the distance from the membrane invagination tip to the closest ribosome found towards the cell interior (26 ± 2 nm vs. 35 ± 3 nm, n = 62 patches per strain, p<0.01) and the width of the exclusion zone at the base of the invagination (98 ± 3 nm vs. 129 ± 7 nm, n = 62 patches per strain, p<0.01). Quantification therefore corroborated a larger ribosome exclusion zone surrounds the endocytic invagination in sla1AAA cells. These results are consistent with the fluorescent microscopy determinations showing increased levels of coat proteins other than clathrin (Sla1, Pan1, Ent1), polymerized actin and actin machinery (Abp1, Las17, Myo5, Vrp1, Bzz1), and scission machinery (Rvs167) in sla1AAA cells. These results also reinforce the idea that Sla1-clathrin binding is needed for consistent progression to late stages of endocytosis, normal levels of actin polymerization and proper membrane shaping.

Figure 9. Impaired Sla1-clathrin binding results in longer membrane invagination and larger ribosome exclusion zone at endocytic sites.

Upper left, electron micrograph demonstrating a typical membrane invagination of an endocytic site in wild type cells. Lower left, electron micrograph demonstrating a membrane invagination of an endocytic site in sla1AAA cells. Notice the typical area devoid of ribosomes around the invagination is larger in sla1AAA cells (quantification described in the text). The white arrow indicates a ribosome. Right, box and whisker plot quantification of membrane invaginations in both wild type and sla1AAA cells showing a difference in the membrane invagination length (P<0.001, N=77 wild type cell patches and N=118 sla1AAA cell patches).

DISCUSSION

While the function of the adaptor protein-clathrin interaction in CME is conceptually clear, studying its importance in live cells has not been straightforward. For example the existence of several clathrin adaptors can result in redundancy/compensation and lack of phenotype when only one is mutated40,44,45. Furthermore, deletion of the adaptor gene can complicate the interpretation of results because the other interactions that adaptors make with cargo and the CME machinery are also lost2,6,22,23. On the other hand, overall clathrin deficiency results in defects beyond CME due to its function in the secretory pathway and endosomes5,19,23. For instance, if clathrin is mutated the CME cargo would not be normally delivered to the plasma membrane in the first place. The sla1AAA allele is unique in demonstrating a defect in endocytosis of CME endogenous cargo with a mutation that specifically disrupts the clathrin-binding motif but preserves all other Sla1 domains29. Also Sla1 functions specifically in CME, thus avoiding confounding factors such as a role in other vesicle transport pathways that could indirectly affect CME.

The lower clathrin levels detected at late stages of endocytosis in sla1AAA cells imply interaction with Sla1 is needed for normal clathrin recruitment even though other clathrin binding adaptors – Yap1801, Ent1 – are present. However, initial clathrin recruitment occurs before Sla1 arrival to endocytic sites10,11. This suggests the Sla1-clathrin interaction is needed for later clathrin recruitment or maintenance of a full clathrin coat as endocytosis progresses but should not be needed at early stages. Supporting this idea, clathrin levels at endocytic sites before Sla1AAA arrival were not affected. It was recently suggested that while a complete clathrin coat already exists at early stages when the membrane is still flat, such membrane bound clathrin exchanges with soluble clathrin while transitioning from flat to curved membrane17,34. This would allow adapting the clathrin configuration of hexagons and pentagons to the changing membrane curvature. Our results are consistent with a model in which interaction with other adaptors recruited at earlier stages bring initial clathrin triskelia to an incipient CME site11,40 and interaction with Sla1 is needed during exchange with soluble clathrin triskelia at later stages, perhaps during the flat-curved membrane transition.

While it is conceptually clear that clathrin recruitment requires binding to adaptor proteins, the converse relationship may also be true. In other words, adaptors may be recruited or stabilized at endocytic coats in part by binding to clathrin, in addition to interacting with cargo and other endocytic proteins. Even though Sla1AAA achieved overall membrane recruitment levels higher than the wild type protein, the rate of recruitment was reduced compared to wild type Sla1. This result is consistent with the idea that binding to clathrin is important for proper adaptor recruitment to endocytic sites.

Endocytosis proceeds through various stages that take place in a reproducible and stereotypical manner1–3,7,10. Several experimental results obtained here underscore the need for adaptor-clathrin interaction and proper clathrin recruitment levels for normal progression of endocytosis:

First, the patch lifetime of early (Ede1, Yap1801), intermediate (Sla1, Pan1, Las17, Ent1) and late (Vrp1, Bzz1, Myo5, Abp1, Rvs167) CME machinery proteins was significantly extended in sla1AAA cells. Moreover, the transition between the various endocytic machinery modules (Δt) was significantly delayed. It was particularly noteworthy to find that the key components activating Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization (Las17, Pan1, Myo5, Vrp1, Bzz1) were present for a significantly longer time before actin polymerization took place in sla1AAA cells. This result highlights a previously unappreciated link between coat formation and activation of actin polymerization.

Second, with the exception of clathrin, the levels of all endocytic machinery proteins studied were higher than normal at the endocytic sites of sla1AAA cells. In particular, the significantly higher levels of Abp1 and expanded ribosome exclusion zone around endocytic sites indicate a larger actin network in sla1AAA cells. Given that actin polymerization is considered the main force driving membrane bending, this result suggests that the clathrin coat normally cooperates in shaping the membrane and that a higher level of actin polymerization compensates when clathrin contribution decreases. Another force believed to cooperate in membrane bending arises from the steric collision of coat proteins such as adaptors on the cytosolic side of the membrane, which is alleviated by invaginating the membrane37,46,47. Again, the higher levels of various proteins in sla1AAA cells could represent a compensatory mechanism to allow endocytosis progression in a situation of reduced clathrin contribution. Alternatively, increased levels of coat and actin network proteins may be caused by the slower rate of vesicle formation that provides more time for additional recruitment of endocytic factors.

Third, the endocytic membrane profile was longer in sla1AAA cells. Given that we only find a deficit of clathrin at CME sites, this result also suggests that a full coat is necessary to produce a normal invagination shape. Interestingly, cells carrying a deletion of the RVS167 gene have shorter endocytic profiles17. Rvs167 is normally recruited to the endocytic site when the invagination transitions from dome shaped to developing parallel membranes ultimately aiding the scission step. Thus, the higher level of Rvs167 observed in sla1AAA cells is consistent with a longer endocytic profile that is able to accommodate more copies of Rvs167. The extra time provided by a slower process of vesicle formation could also allow for additional recruitment of Rvs167. The enhanced levels of Rvs167 could also represent another compensatory mechanism to alleviate the lack of clathrin coat contribution to membrane bending, perhaps at the invagination tip-neck transition. Interestingly, a recent superresolution microscopy analysis suggested Sla1 forms a ring at the invagination tip-neck transition48. Consequently, sla1AAA cells may lack clathrin recruitment specifically at a key region where the clathrin cage meets the invagination neck. Such a mechanism would help explain clathrin contribution to the regularity of vesicle scission and the resulting vesicle size49.

Several studies previously reported the phenotype of strains carrying a deletion of the clathrin heavy chain gene (CHC1) or clathrin light chain gene (CLC1). The fact that in yeast clathrin is not needed to produce endocytic invagination profiles as observed by electron microscopy was first reported using chemical fixation18 and then high pressure freezing and freeze substitution of chc1Δ cells49. The first study also found that immunogold labeling of Sla1 decorated a higher proportion of longer endocytic invaginations in chc1Δ cells than in wild type cells18. The second study found that the endocytic invaginations in chc1Δ cells have approximately the same morphology as in wild type cells49. Importantly, fluorescence microscopy studies of live chc1Δ cells and clc1Δ cells demonstrated less endocytic sites labeled by Sla1-GFP, more cytosolic Sla1-GFP background and a shorter Sla1-GFP lifetime at endocytic sites compared with wild type cells10,50. These results contrast with our findings of Sla1AAA–GFP displaying more patches per cell, longer lifetime, higher membrane/cytosol proportion, and longer invagination profiles compared with wild type Sla1-GFP. While the reason for the different phenotypes is not entirely clear, several possibilities can be envisioned:

As previously mentioned, vesicular transport in chc1Δ cells and clc1Δ cells is more globally affected than in sla1AAA cells due to lost clathrin function at the trans-Golgi Network and endosomes. Endocytosis phenotypes observed in chc1Δ cells and clc1Δ cells may therefore be partly indirect and reflect factors such as a reduced flux of membrane and protein cargo requiring endocytosis/recycling. This would explain for instance the lower number of endocytic sites observed in chc1Δ cells and clc1Δ cells10,50.

In sla1AAA cells early clathrin recruitment and endocytic site initiation is normal due to the function of other clathrin binding adaptors. Subsequently, the presence of assembled clathrin may impede progression to later stages of endocytosis. If as suggested above Sla1 normally functions in the remodeling of assembled clathrin during the flat-curved transition, the inability of Sla1AAA to bind clathrin may delay such transition. Sla1 would still be recruited to endocytic sites (although at a slower rate) via interactions with various other machinery components and transmembrane protein cargo. Such a scenario with normal endocytic site initiation but slower progression would explain the longer Sla1AAA lifetime and, consequently, the increased number of patches detected at steady state relative to wild type Sla1.

In addition to binding clathrin, the Sla1 vCB sequence (LLDLQ) binds intramolecularly to the Sla1 SAM domain29. Interestingly, the Sla1 SAM domain can homo-oligomerize thus driving Sla1 homo-oligomerization. The region of the SAM domain surface involved in binding vCB overlaps with the SAM domain homo-oligomerization surface. Accordingly, vCB was proposed to act as a switch that binds to clathrin or the Sla1 SAM domain thereby mediating clathrin recruitment or inhibiting Sla1 self-oligomerization29. Based on this model, the vCB mutation should increase the proportion of oligomeric Sla1, which is expected to occur while concentrated at endocytic sites29, thus contributing to the higher Sla1AAA patch/cytosol ratio observed here. Considering Sla1 brings Las17 to endocytic sites41 and that Sla1 and Las17 interact with many other endocytic proteins, a higher level of Sla1AAA oligomerization/recruitment may then cause an increased recruitment of other coat and actin network components.

The phenotype of sla1AAA cells is broader than the one found in cells with mutated canonical clathrin-box and W-box binding sites on the clathrin heavy chain N-terminal domain51. The more recent discovery of additional binding sites on the clathrin heavy chain N-terminal domain likely explain this difference and the mild phenotype of such mutant52.

In summary, this work shows the clathrin-Sla1 adaptor protein interaction is important for recruitment of both proteins to endocytic sites, progression through various stages of endocytosis (especially actin polymerization), and normal shaping of the invagination membrane. This work advances our understanding of the function of the adaptor-clathrin interaction and also opens new questions. For example, in the future it will be important to further explore the mechanistic link between coat formation and actin polymerization.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Strains

Standard methods were utilized to generate SDY1031 (MATa ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL EDE1-RFP::HIS3) which was then mated with SDY063 (MATα ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL SLA1-GFP::TRP1) or GPY4918 (MATα ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL CHC-RFP::KAN, sla1AAA-GFP::TRP1)29,41,53,54. The corresponding diploid cells were then subjected to sporulation and tetrad dissection to generate haploid segregant SDY1033 (MAT ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL EDE1-RFP::HIS3, SLA1-GFP::TRP1) and SDY1034 (MAT ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL EDE1-RFP::HIS3, sla1AAA-GFP::TRP1). Standard methods were utilized to generate SDY1032 (MATa ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL PAN1-RFP::HIS3) which was then mated with SDY063 and the corresponding diploid cells were then subjected to sporulation and tetrad dissection to generate haploid segregant SDY1035 (MAT ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL PAN1-RFP::HIS3, SLA1-GFP::TRP1).

The vCB mutation (LLDLQ to AAALQ) was introduced into the endogenous SLA1 gene in GPY1805 (MATa ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL ste2Δ::LEU2) following a two-step approach similar to the one previously described30,31. For the first step, sequences flanking the Sla1 SHD2 domain and vCB motif, nucleotides 1207–1410 and 2427–2589 were amplified by PCR and cloned into the NotI/BamHI and EcoRI/SalI sites of pBluescriptKS, respectively. A PCR fragment containing URA3 was then subcloned into the BamHI/EcoRI sites. The resulting construct was cleaved with NotI/ SalI and the URA3 fragment was introduced by lithium acetate transformation53 into GPY1805 to generate SDY057 in which SHD2 and the vCB were replaced by URA3. In the second step, BsgI/AgeI fragments from pBKS-Sla1-1207-2589 (SLA1 nucleotides 1207–2589 subcloned into the NotI/SalI sites of pBluescriptKS) containing the LLDLQ-to-AAALQ mutation was cotransformed with pRS313 (HIS3)55 into SDY057. His+ colonies were replica-plated onto agar medium containing 5-fluorotic acid to identify cells in which the mutant sequence replaced URA3, thus generating strain SDY059 (sla1AAA). Standard methods were subsequently applied to strain SDY059 to generate SDY1027 (MATa ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL ste2Δ::LEU2, sla1AAA, PAN1-GFP::TRP1, EDE1-mCHERRY::HIS3) and to GPY1805 to generate wild type control strain SDY1025 (MATa ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL ste2Δ::LEU2, PAN1-GFP::TRP1, EDE1-mCHERRY::HIS3).

The wild type control and vCB mutant yeast strains used for biochemical analysis shown in Figure 1 were previously described: TVY614 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 pep4::LEU2 prb1::HISG prc1::HIS3) and GPY4913 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 sla1AAA pep4::LEU2 prb1::HISG prc1::HIS3)29,56.

The vCB mutation (LLDLQ to AAALQ) was also introduced into the endogenous SLA1 gene in SDY358 (MATα ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL SLA1-RFP::Kan) following a similar two-step approach as described above. The first step generated SDY855 in which the third SH3 domain, SHD2 and vCB of SLA1 were replaced by URA3. In the second step, the BsgI/AgeI fragment containing the LLDLQ-to-AAALQ mutation cotransformed with pRS314 (TRP1) into SDY855. Trp+ colonies were replica-plated onto agar medium containing 5-fluorotic acid to identify cells in which the mutant sequence replaced URA3, thus generating strain SDY878. This strain was then mated with strain expressing CHC-GFP from the endogenous locus (MATa his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15-Δ0, ura3Δ0, CHC-GFP::HIS3) and the resulting diploid cells were subjected to sporulation and tetrad dissection to generate haploid segregant SDY884 (MATα his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15-Δ0, ura3Δ0, CHC-GFP::HIS3, sla1AAA-RFP::Kan). Wild type control SDY650 (MATα his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15-Δ0, ura3Δ0, CHC-GFP::HIS3, SLA1-RFP::Kan) was generated by crossing the corresponding wild type strains. Strains GPY4916 (MATα, ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9, CHC-RFP::Kan, SLA1-GFP::TRP1) GPY4918 (MATα, ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9, CHC-RFP::Kan, sla1AAA-GFP::TRP1) were previously described29.

Standard methods were applied to wild type (SDY087) and sla1AAA (SDY059) cells to tag the endogenous genes and generate strains expressing the following protein pairs: Las17-GFP and Abp1-mCherry (SDY1029, wt; SDY1023, sla1AAA); Vrp1-GFP and Abp1-mCherry (SDY860, wt; SDY862, sla1AAA); Myo5-GFP and Abp1-mCherry (SDY871, wt; SDY873, sla1AAA); Bzz1-GFP and Abp1-mCherry (SDY864, wt; SDY870, sla1AAA); Rvs167-GFP and Abp1-mCherry (SDY856, wt; SDY858, sla1AAA). Standard methods were also applied to wild type (SDY358) and sla1AAA (SDY878) cells to tag the endogenous YAP1801 and ENT1 genes with GFP and generate strains SDY1107 (MATα ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL SLA1-RFP::Kan, YAP1801-GFP::TRP1), SDY1108 (MATα ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL sla1AAA-RFP::Kan, YAP1801-GFP::TRP1), SDY1103 (MATα ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL SLA1-RFP::Kan, ENT1-GFP::TRP1), SDY1105 (MATα ura3-52, leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200,trp1-Δ901, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9 GAL –MEL sla1AAA-RFP::Kan, ENT1-GFP::TRP1),

Fluorescent Microscopy

Fluorescent microscopy imaging was performed using an Olympus IX81 spinning disk confocal microscope as described57–59. Cells were grown to early log phase and imaged at room temperature. Time laps images where collected every 1, 2, 3 or 5sec according to the length of the patch lifetimes. Imaging software Slidebook6 (3I, Denver, CO) was used for capturing and analysis of images. Data of endocytic patch lifetimes was obtained by drawing a trace around imaged endocytic sites and measuring the average fluorescent intensity for the masked area. Peak patch fluorescence intensities and patch/cytosol fluorescence intensities were measured by drawing a mask on endocytic sites and internal regions, and then normalizing the intensity to that of the background. Kaleidagraph software was used for patch-lifetime determination of fluorescently tagged proteins by integrating the intensities of each consecutive time point and establishing the minimum and maximum value of the integral as previously described41. Sla1-GFP and Pan1-RFP recruitment rates were determined by measuring the slope of the linear portion of fluorescence intensity over time plots in the region corresponding to 25% to 50% of the maximal fluorescence. For Figure 2C, cells expressing CHC-RFP and Sla1-GFP or Sla1AAA-GFP were treated with 250uM Latrunculin A in SD complete media for 20 minutes before being imaged as described11. Statistical significance between wild type and sla1AAA cells was determined using an unpaired student’s t-test (Graph-pad Software) to determine the SEM and P values.

Biochemical Assay

To obtain total cell extracts, 9mL of yeast were cultured in YPD media to an OD500 of 1.0, pelleted via centrifugation, washed 2 times with 2mL of sterile diH2O and placed on ice. 400uL of 0.5mm glass beads were then added to each cell pellet along with 100uL of Buffer A (10mm Hepes pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells were then broken by vortexing at 4°C for 1min. Samples were subjected to centrifugation at 16,000×g, 4°C, for 10 min to remove unbroken cells and nuclei. The supernatant was removed and placed into tubes for ultracenrifugation at 75,000rpm for 20 minutes using a Beckman TLA 100.3 rotor to separate the membrane fraction from the cytosol. The cytosolic fraction was removed and the pelleted membrane fraction was resuspended in RIPA buffer (150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1%Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 20mM Tris pH 7.4). The solubilized membrane fraction was then spun at 16,000×g, 4°C, for 15 min and the supernatant was removed and placed in a new culture tube on ice. Equivalent amounts of membrane and cytosol fractions were boiled in Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting as described60. Imaging of immunoblots was performed by use of ImageQuant Las500 from GE and quantification of band intensity was performed using ImageJ software61.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Yeast cultures SDY063 (wild type) and GPY4918 (sla1AAA) were grown in YPD media to an OD500 of 0.5, quickly concentrated by filtration, and subjected to high pressure freezing, freeze-substitution, and embedding in Lowicryl HM20 resin as described previously62–64. This was followed by collecting 90nm sections of the resin embedded cells onto formvar coated copper grids. The grids were then stained with 2% uranyl acetate prepared in a 70% methanol 30% water mixture for 15 minutes in the dark. Grids were then washed in a 70% methanol 30% water mixture for 20 secs. This was followed by incubation in Reynolds lead stain for 3 minutes in the dark, followed by four 50 second washes in diH20. Grids were then subjected to transmission electron microscopy using a JEOL2000 microscope. Membrane invagination length and ribosome exclusion zone were measured using Adobe Photoshop software. Statistical significance between membrane invagination lengths and the size of ribosome exclusion zones was determined using an unpaired student’s t-test (Graph-pad Software) to determine the SEM and P value.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Defective Sla1-clathrin binding results in a higher number of endocytic sites labeled by Sla1-GFP. Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing Sla1AAA-GFP or Sla1wt-GFP. Left, panels show one representative frame of a movie. Scale bar, 1µm. The number of endocytic sites was determined using a single random frame per cell analyzing the mother cell, where endocytic patches are more spatially separated. Right, quantification represented as box and whisker (minimum-maximum) plots showed higher number of patches per cell for Sla1AAA-GFP relative to Sla1wt-GFP (P=0.001, N=271 wild type cell patches and 335 sla1AAA cell patches).

Figure S2: Defective Sla1-clathrin binding does not affect clathrin levels at early stages of endocytosis. Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing both CHC-GFP and Sla1AAA-RFP from the corresponding endogenous locus (sla1AAA cells). Wild type cells expressing CHC-GFP and Sla1wt-RFP were analyzed in parallel for comparison. Left, panels show one representative frame of a movie. Scale bar, 1µm. Given that CHC-GFP also localizes to internal organelles, the presence of Sla1 was used as a reference to identify CHC-GFP localized at endocytic sites. After endocytic patch identification, movies were rewound to analyze the CHC-GFP fluorescence during the period preceding the arrival of Sla1-RFP or Sla1AAA-RFP. The CHC-GFP fluorescence intensity was recorded except for the time points in which internal structures interfered by overlapping with endocytic sites as determined by visual inspection of each patch frame by frame. Right, quantification represented as box and whisker (minimum-maximum) plots demonstrates the CHC-GFP levels at endocytic sites in sla1AAA are indistinguishable from wild type cells (P=0.45, N=155 patches from wild type cells and N=133 patches from sla1AAA cells).

SYNOPSIS.

Mutation of the clathrin-binding motif in the Sla1 endocytic adaptor (sla1AAA) causes a defect in endocytosis of endogenous cargo. This study shows that cells expressing sla1AAA have normal clathrin levels at early stages of endocytosis but reduced clathrin levels at late stages of endocytosis, after the arrival of sla1AAA. Defective Sla1-clathrin interaction also leads to a delayed progression through stages of endocytosis, especially between the arrival of the Arp2/3 complex activation machinery and the initiation of actin polymerization. Ultimately, an impaired Sla1-clathrin interaction causes a dramatic increase in overall level of actin and other machinery proteins at sites of endocytosis as well as a longer membrane invagination.

Acknowledgments

We thank Laurie Stargell for generous gift of yeast strains, Judith Boyle and Tom Giddings for help with high pressure freezing and electron microscopy, and Andrea Ambrosio for help with figure preparation. This work was supported by NSF grant 1616775 and NIH grant HL106186. T.O.T. acknowledges American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, T. Tolsma, S. Di Pietro; investigation, T. Tolsma, L. Cuevas; formal analysis, T. Tolsma; writing, T. Tolsma, S. Di Pietro; visualization, T. Tolsma, S. Di Pietro; funding acquisition, S. Di Pietro; resources, S. Di Pietro; and supervision, S. Di Pietro.

References

- 1.Goode BL, Eskin JA, Wendland B. Actin and endocytosis in budding yeast. Genetics. 2015;199(2):315–358. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boettner DR, Chi RJ, Lemmon SK. Lessons from yeast for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(1):2–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinberg J, Drubin DG. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis in budding yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirchhausen T, Owen D, Harrison SC. Molecular structure, function, and dynamics of clathrin-mediated membrane traffic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(5):a016725. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodsky FM. Diversity of clathrin function: new tricks for an old protein. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:309–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reider A, Wendland B. Endocytic adaptors--social networking at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 10):1613–1622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaksonen M, Sun Y, Drubin DG. A pathway for association of receptors, adaptors, and actin during endocytic internalization. Cell. 2003;115(4):475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor MJ, Perrais D, Merrifield CJ. A high precision survey of the molecular dynamics of mammalian clathrin-mediated endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(3):e1000604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyon JB, Zeitler B, Cheng J, et al. Rapid and efficient clathrin-mediated endocytosis revealed in genome-edited mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(3):331–337. doi: 10.1038/ncb2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaksonen M, Toret CP, Drubin DG. A modular design for the clathrin- and actin-mediated endocytosis machinery. Cell. 2005;123(2):305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newpher TM, Smith RP, Lemmon V, Lemmon SK. In vivo dynamics of clathrin and its adaptor-dependent recruitment to the actin-based endocytic machinery in yeast. Dev Cell. 2005;9(1):87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun Y, Martin AC, Drubin DG. Endocytic internalization in budding yeast requires coordinated actin nucleation and myosin motor activity. Dev Cell. 2006;11(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toshima JY, Toshima J, Kaksonen M, Martin AC, King DS, Drubin DG. Spatial dynamics of receptor-mediated endocytic trafficking in budding yeast revealed by using fluorescent alpha-factor derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(15):5793–5798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601042103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reider A, Barker SL, Mishra SK, et al. Syp1 is a conserved endocytic adaptor that contains domains involved in cargo selection and membrane tubulation. EMBO J. 2009;28(20):3103–3116. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stimpson HE, Toret CP, Cheng AT, Pauly BS, Drubin DG. Early-arriving Syp1p and Ede1p function in endocytic site placement and formation in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(22):4640–4651. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-05-0429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boettner DR, D'Agostino JL, Torres OT, et al. The F-BAR protein Syp1 negatively regulates WASp-Arp2/3 complex activity during endocytic patch formation. Curr Biol. 2009;19(23):1979–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kukulski W, Schorb M, Kaksonen M, Briggs JA. Plasma membrane reshaping during endocytosis is revealed by time-resolved electron tomography. Cell. 2012;150(3):508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idrissi FZ, Blasco A, Espinal A, Geli MI. Ultrastructural dynamics of proteins involved in endocytic budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(39):E2587–2594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202789109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchhausen T. Clathrin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:699–727. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearse BM. Clathrin: a unique protein associated with intracellular transfer of membrane by coated vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73(4):1255–1259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.4.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson MS. Forty Years of Clathrin-coated Vesicles. Traffic. 2015;16(12):1210–1238. doi: 10.1111/tra.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen DJ, Collins BM, Evans PR. Adaptors for clathrin coats: structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:153–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson MS. Adaptable adaptors for coated vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14(4):167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dell'Angelica EC, Klumperman J, Stoorvogel W, Bonifacino JS. Association of the AP-3 adaptor complex with clathrin. Science. 1998;280(5362):431–434. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ter Haar E, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T. Peptide-in-groove interactions link target proteins to the beta-propeller of clathrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(3):1096–1100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wendland B, Steece KE, Emr SD. Yeast epsins contain an essential N-terminal ENTH domain, bind clathrin and are required for endocytosis. EMBO J. 1999;18(16):4383–4393. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Traub LM, Bonifacino JS. Cargo recognition in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(11):a016790. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mettlen M, Loerke D, Yarar D, Danuser G, Schmid SL. Cargo- and adaptor-specific mechanisms regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2010;188(6):919–933. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Pietro SM, Cascio D, Feliciano D, Bowie JU, Payne GS. Regulation of clathrin adaptor function in endocytosis: novel role for the SAM domain. EMBO J. 2010;29(6):1033–1044. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard JP, Hutton JL, Olson JM, Payne GS. Sla1p serves as the targeting signal recognition factor for NPFX(1,2)D-mediated endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;157(2):315–326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahadev RK, Di Pietro SM, Olson JM, Piao HL, Payne GS, Overduin M. Structure of Sla1p homology domain 1 and interaction with the NPFxD endocytic internalization motif. EMBO J. 2007;26(7):1963–1971. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piao HL, Machado IM, Payne GS. NPFXD-mediated endocytosis is required for polarity and function of a yeast cell wall stress sensor. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(1):57–65. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu K, Hua Z, Nepute JA, Graham TR. Yeast P4-ATPases Drs2p and Dnf1p are essential cargos of the NPFXD/Sla1p endocytic pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(2):487–500. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avinoam O, Schorb M, Beese CJ, Briggs JA, Kaksonen M. ENDOCYTOSIS. Endocytic sites mature by continuous bending and remodeling of the clathrin coat. Science. 2015;348(6241):1369–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boulant S, Kural C, Zeeh JC, Ubelmann F, Kirchhausen T. Actin dynamics counteract membrane tension during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(9):1124–1131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ehrlich M, Boll W, Van Oijen A, et al. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits. Cell. 2004;118(5):591–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stachowiak JC, Brodsky FM, Miller EA. A cost-benefit analysis of the physical mechanisms of membrane curvature. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(9):1019–1027. doi: 10.1038/ncb2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wendland B, McCaffery JM, Xiao Q, Emr SD. A novel fluorescence-activated cell sorter-based screen for yeast endocytosis mutants identifies a yeast homologue of mammalian eps15. J Cell Biol. 1996;135(6 Pt 1):1485–1500. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang HY, Xu J, Cai M. Pan1p, End3p, and S1a1p, three yeast proteins required for normal cortical actin cytoskeleton organization, associate with each other and play essential roles in cell wall morphogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(1):12–25. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.12-25.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maldonado-Baez L, Dores MR, Perkins EM, Drivas TG, Hicke L, Wendland B. Interaction between Epsin/Yap180 adaptors and the scaffolds Ede1/Pan1 is required for endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(7):2936–2948. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feliciano D, Di Pietro SM. SLAC, a complex between Sla1 and Las17, regulates actin polymerization during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(21):4256–4272. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geli MI, Lombardi R, Schmelzl B, Riezman H. An intact SH3 domain is required for myosin I-induced actin polymerization. EMBO J. 2000;19(16):4281–4291. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Idrissi FZ, Grotsch H, Fernandez-Golbano IM, Presciatto-Baschong C, Riezman H, Geli MI. Distinct acto/myosin-I structures associate with endocytic profiles at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2008;180(6):1219–1232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brach T, Godlee C, Moeller-Hansen I, Boeke D, Kaksonen M. The initiation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis is mechanistically highly flexible. Curr Biol. 2014;24(5):548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keyel PA, Mishra SK, Roth R, Heuser JE, Watkins SC, Traub LM. A single common portal for clathrin-mediated endocytosis of distinct cargo governed by cargo-selective adaptors. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(10):4300–4317. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stachowiak JC, Schmid EM, Ryan CJ, et al. Membrane bending by protein-protein crowding. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(9):944–949. doi: 10.1038/ncb2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snead WT, Hayden CC, Gadok AK, et al. Membrane fission by protein crowding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(16):E3258–E3267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616199114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Picco A, Mund M, Ries J, Nedelec F, Kaksonen M. Visualizing the functional architecture of the endocytic machinery. Elife. 2015:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kukulski W, Picco A, Specht T, Briggs JA, Kaksonen M. Clathrin modulates vesicle scission, but not invagination shape, in yeast endocytosis. Elife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.16036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newpher TM, Lemmon SK. Clathrin is important for normal actin dynamics and progression of Sla2p-containing patches during endocytosis in yeast. Traffic. 2006;7(5):574–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collette JR, Chi RJ, Boettner DR, et al. Clathrin functions in the absence of the terminal domain binding site for adaptor-associated clathrin-box motifs. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(14):3401–3413. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lemmon SK, Traub LM. Getting in touch with the clathrin terminal domain. Traffic. 2012;13(4):511–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983;153(1):163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Longtine MS, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14(10):953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122(1):19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vida TA, Emr SD. A new vital stain for visualizing vacuolar membrane dynamics and endocytosis in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1995;128(5):779–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farrell KB, Grossman C, Di Pietro SM. New Regulators of Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis Identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by Systematic Quantitative Fluorescence Microscopy. Genetics. 2015;201(3):1061–1070. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.180729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farrell KB, McDonald S, Lamb AK, Worcester C, Peersen OB, Di Pietro SM. Novel function of a dynein light chain in actin assembly during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2017;216(8):2565–2580. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201604123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feliciano D, Tolsma TO, Farrell KB, Aradi A, Di Pietro SM. A second Las17 monomeric actin-binding motif functions in Arp2/3-dependent actin polymerization during endocytosis. Traffic. 2015;16(4):379–397. doi: 10.1111/tra.12259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bultema JJ, Ambrosio AL, Burek CL, Di Pietro SM. BLOC-2, AP-3, and AP-1 proteins function in concert with Rab38 and Rab32 proteins to mediate protein trafficking to lysosome-related organelles. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(23):19550–19563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.351908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ambrosio AL, Boyle JA, Di Pietro SM. Mechanism of platelet dense granule biogenesis: study of cargo transport and function of Rab32 and Rab38 in a model system. Blood. 2012;120(19):4072–4081. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-420745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meehl JB, Giddings TH, Jr, Winey M. High pressure freezing, electron microscopy, and immuno-electron microscopy of Tetrahymena thermophila basal bodies. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;586:227–241. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-376-3_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bultema JJ, Boyle JA, Malenke PB, et al. Myosin vc interacts with Rab32 and Rab38 proteins and works in the biogenesis and secretion of melanosomes. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(48):33513–33528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.578948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ambrosio AL, Boyle JA, Aradi AE, Christian KA, Di Pietro SM. TPC2 controls pigmentation by regulating melanosome pH and size. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(20):5622–5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600108113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Defective Sla1-clathrin binding results in a higher number of endocytic sites labeled by Sla1-GFP. Live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing Sla1AAA-GFP or Sla1wt-GFP. Left, panels show one representative frame of a movie. Scale bar, 1µm. The number of endocytic sites was determined using a single random frame per cell analyzing the mother cell, where endocytic patches are more spatially separated. Right, quantification represented as box and whisker (minimum-maximum) plots showed higher number of patches per cell for Sla1AAA-GFP relative to Sla1wt-GFP (P=0.001, N=271 wild type cell patches and 335 sla1AAA cell patches).