Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate immediate postoperative pain control modalities after total knee arthroplasty at the author’s specific institution and compare those modalities with patient satisfaction, rehabilitation status, and length of hospital stay.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of 101 patients who underwent total knee arthroplasty from 2013 to 2016 was performed. Data was collected including the pain control modality, total pain medication consumption, physical therapy progress, length of hospital stay and Visual Analog Scores. Analysis was then performed using SAS proprietary software. Results were reported as statistically significant if p value was less than 0.05.

Results

Multiple variables proved to be statistically significant (p value <0.05) in this particular study. Patients who received Valium required more morphine equivalents on average and reported higher Visual Analog Scores (VAS). For those patients who received a lower extremity nerve block pre operatively, there was a decrease in morphine equivalents on postoperative day one and lower VAS. For those patients who received the continuous pain pump, ON-Q postoperatively, there was an average increase in length of hospital stay by one day and a decrease in ambulation on postoperative day one. Also, females required less overall pain medication on postoperative days two and three compared to their male counterparts. Finally, there was no statistically significant difference for those patients who received Lyrica (pregabalin) or NSAIDS for the parameters that were measured in this study.

Conclusions

Postoperative pain control modalities after total knee arthroplasty are highly variable among physicians. This variability has allowed researchers to review each modality and compare and contrast the benefits with the potential adverse effects of these medications on total knee replacement outcomes. The data in this study suggests that the use of Valium is correlated with increased pain medication consumption and decreased patient satisfaction. Data from this study also reveals that patients who underwent preoperative nerve blocks experienced decreased pain on postoperative day one and greater patient satisfaction. The most notable contribution of this study was the discovery of the adverse effects of the continuous pain pump, ON-Q. Patients treated with this modality had decreased ambulation on postoperative day one and on average remained in the hospital one extra day, a variable that significantly increases the cost of a total knee arthroplasty for the hospital, the surgeon and the patient. Even though this data is significant, further studies should be performed to enhance our knowledge of postoperative pain control for these patients.

Keyword: ON-Q

1. Introduction/background

Total knee arthroplasty has become one of the most popular and most performed surgical procedures in the field of orthopedics over the past thirty years. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, roughly 600,000 total knee replacements are performed in the U.S. each year. By the year 2030, the number of total knee replacements is expected to increase to more than 3.5 million per year, a 673% increase1. With this increased growth, new research and clinical studies have been performed in order to decrease costs and increase overall operative room efficiency. One particular aspect of the total knee replacement that has been studied, although not extensively is postoperative pain control modalities and how it relates to post operative satisfaction, rehab and cost. This study aims to isolate specific postoperative pain control modalities at one institution and compare those modalities with patient satisfaction, rehab status, and total time in hospital.

More than half of the patients who undergo surgery experience inappropriate levels of postoperative pain, despite increased investigation in pain management.2, 3, 4, 5 Patients who have specifically undergone orthopedic surgery have been considered especially difficult to manage pain in the postoperative setting.6, 7, 8, 9 Approximately half of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patients present with extreme pain immediately after surgery.10, 11, 12 Furthermore, uncontrolled postoperative pain leads to increased stress and prolonged immobilization, which can secondarily promote cardiac events, decreased pulmonary function, gastrointestinal complications, such as an ileus, and thrombus formation.13,14 A rapid increase in stress hormones and sleep disorders due to severe pain can worsen the already decreased immunity, which leads to higher risk of infection and prolonged wound healing. This may then also affect the cognitive status of elderly patients, leading to delirium and anxiety.9, 10, 11, 12 Uncontrolled severe immediate postoperative pain can also develop into chronic pain due to the sensitization and up regulation of the nociceptors in the nervous system.15,16 It has been well documented that uncontrolled pain can compromise early rehabilitation and recovery, resulting in increased length of hospitalization, increased medical costs, and increased burden on the health care provider.2,3,9, 10, 11, 12

Pain after TKA is a particularly serious problem, considering the substantially increasing TKA use and the aging population. Studies have shown that multimodal analgesic pain protocols have led to decreased pain and decreased hospital stays17 but further studies of specific modalities need to be completed. This particular study sought to compare specific postoperative measurable variables based on the type of pain medication the patient was taking after surgery.

2. Data methods

A retrospective chart review of 101 patients who underwent total knee arthroplasty at the author’s institution from 2013 to 2016 was performed. Data was collected including gender, and pain control modality. Then based on individual pain control modalities, total pain medication consumption (graded in morphine equivalents per hour), physical therapy progress (graded in number of feet ambulated per day), length of stay (measured in days), and patient satisfaction of pain control (measured with Visual Analog Scores, VAS: measured 1–10, 1 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain) were measured. Analysis was then performed using SAS (statistical analysis system) proprietary software version 9.2. Results were reported as statistically significant if p value was less than 0.05 as reported in ANOVA (analysis of variance) tables comparing the (Fig. 3).

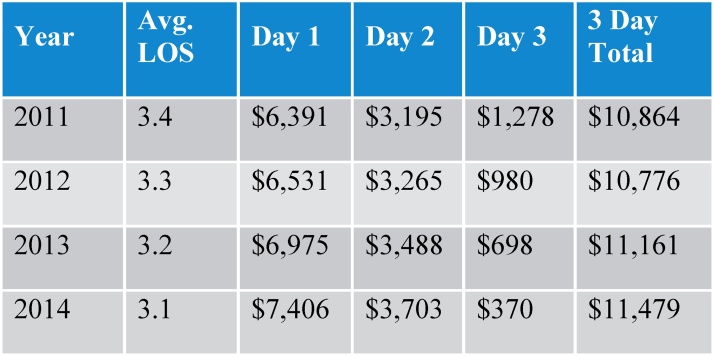

Fig. 3.

Medicare Reimbursement for total joint replacements by day.29

3. Results

Of the 101 patients included in the retrospective review, 63 were female and 38 were male. The average age was 65.93 years, ranging from 46 to 86 years. The average length of stay in the hospital was 2.81 days. Average Mill-equivalents (M-eq) of morphine used was 25.65 units on postoperative day (POD) 0, 56.64 M-eq on POD 1, 49.03 on POD 2, and 34.68 on POD 3. Average patient satisfaction of pain control, measured in visual analog scores (VAS) was 2.74 POD 0, 4.01 POD 1, 4.24 POD 2, and 3.38 POD 3. Average ambulation of patients was 2.90 feet POD 0; 85.53 feet POD 1; 147.31 feet POD2; and 100.37 feet POD 3.

Gender played a role in postoperative pain control. Males required more M-eq of morphine on average on POD 2 and 3 than females. POD 2 (p value 0.017), males required 62.83 M-eq of morphine whereas females required 41.24 M-eq. On POD 3 (p value 0.025), males required 48.89 M-eq of morphine and females required 25.86 M-eq of morphine.

Thirty patients in the study did receive Lyrica (pregabalin), there was no statistical significance between groups in any of the outcome variables after receiving this medication. Seventy-five patients in the study received generic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS), and there was no statistical significance between groups in any of the outcome variables after receiving this medication.

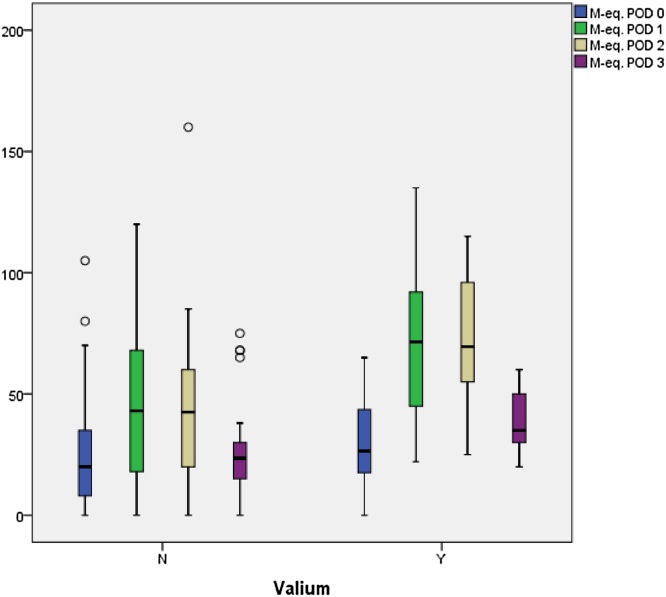

Thirty one patients received Valium, and these patients had a statistically significant increase in amount of M-eq of morphine needed each day for pain control: POD 0 (p value 0.049) average M-eq of morphine needed was 33.35 compared to 25.65 without valium; POD 1 (p value 0.001) M-eq of morphine needed was 79.55 compared with 56.64 without valium; POD 2 (p value 0.001) M-eq of morphine needed was 69.0 compared to 49.03 on average without valium and POD 3 (p value 0.023) M-eq of morphine needed was 49.17 compared to 34.68 without valium. Accordingly, there was statistically significant increase in Visual analog scores (VAS). Patients who received Valium reported more pain, by roughly one point than those who did not receive Valium on POD 1 (p value 0.006) and POD 2 (p value 0.003).

Eighty-six patients did receive a lower extremity nerve block prior to the procedure. There was a significant decrease in the amount of M-eq of morphine needed on POD 0 (p value 0.002) for those patients from 25.65 units on average without a block to 22.36 units for those with a block. There was a decrease in VAS on POD 0 (p value 0.003) from 2.74 on average to 2.16 for those patients who received a nerve block.

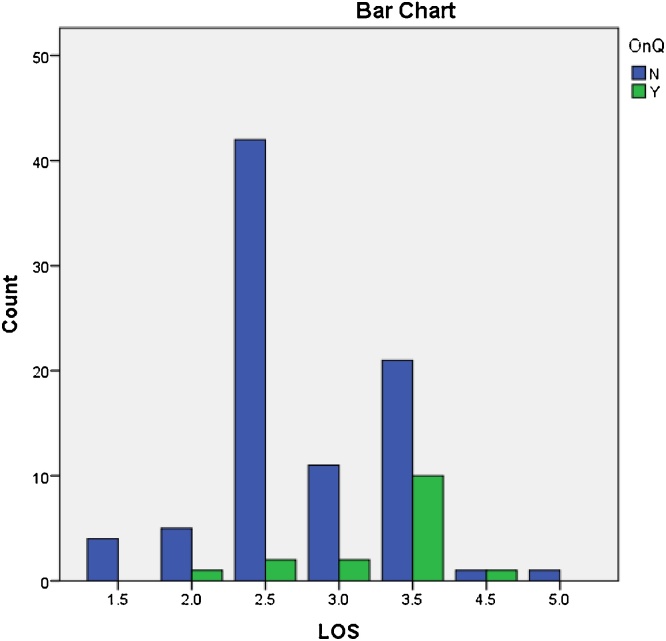

Finally, Sixteen patients did receive the brand name On-Q pain pump with continuous pain medication release while in the hospital. There was a statistically significant (p value 0.001) increase in length of hospital stay for those patients from 2.81 days without On-Q pump to an average of 3.50 days with the On-Q pump. Also, those with the On-Q pump only ambulated on average 40.94 feet on POD 1 (p value 0.001) compared to 85.53 feet for those without the pump.

4. Discussion

4.1. Gender differences

In this particular study, males required more Mil-equivalents of morphine on postoperative days one and two than females. Although gender differences have been studied for many years, most studies state that the female gender is more sensitive to painful stimulus than males.18 According to Melchior et al in the Journal of Neuroscience 2016, women are overrepresented in clinical pain. They also have a lower pain threshold in most of experimental pain modalities and more brain activity in cortical regions that are related to the affective pain component. Although this article proves the opposite of our results, it also states that in the specific pain category of osteoarthritis, males have higher pain ratings after the age of 75. The discrepancy between published data and the results of this study can be explained secondary to weaknesses in the study. First, patients were not isolated based upon the amount of pain medications they were taking before the surgery, which could definitely skew the results. Second, the sample size was small enough that it may not represent the population as a whole. In future studies, using a larger patient population would be beneficial in further evaluating this discrepancy.

4.2. Non-opioid pain medications

The non-opioid pain medications tracked in this particular study were Lyrica (generic name: pregabalin), and generic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS). Although the use of these mediations in this particular retrospective review were not statistically significant in the control of and/or decrease of post operative pain, there have been many studies that promote their use as an integral part of multi-modal pain control therapy. According to the American Pain Society, systemic pharmacological multi modal pain control for total knee arthroplasty includes opioid narcotics, NSAIDS, and gabapentin. Randomized trials have shown that multimodal analgesia involving simultaneous use of combinations of several medications acting at different receptors or one or more medications administered through different techniques (e.g., systemically and neuraxially) is associated with superior pain relief and decreased opioid consumption compared with use of a single medication administered through one technique.19 As illustrated, there is a clearly a published benefit to these medications even though our study did not show significant data to support.

4.3. Valium

Valium (generic name: diazepam) is a medication in the benzodiazepine family that typically produces a calming effect. It has been used to treat anxiety, muscle spasms, seizures, restless leg syndrome, and alcohol withdrawal syndrome.20 In the study, those patients who did receive Valium had a statistically significant increase in the amount of Mil-equivalents of morphine needed each day for pain control (Fig. 1). According to Jones et al, research has shown that opioids and benzodiazepines exert significant modulatory effects on one another. Specifically, benzodiazepines may alter the pharmacokinetics of opioids. In a controlled experiment with rats, their investigation revealed that diazepam was a non-competitive inhibitor of methadone metabolism.21 Essentially this data suggests that taking both Valium and opioid medications together will give a stronger pain relief/euphoria sensation. We cannot state that this is the reason why the patients on Valium in the study requested/required more opioid pain medication, but it is an interesting correlation that needs to be investigated further.

Fig. 1.

Effect of Valium on M-Eq of morphine consumption.

4.4. Nerve block

The femoral nerve block for TKA is a well-documented option for pain control. In the past, surgeons could only rely on intravenous and oral pain medications for postoperative pain control, and nerve blocks have now proven to be efficacious alternatives to pharmacotherapy. Proponents of the femoral nerve block state that with the block, the patient does not have to endure the side effects of general anesthesia which include nausea, vomiting and systemic sedation. These proponents state that bypassing general anesthesia allows the patient to ambulate earlier and perhaps decrease the risk of postoperative deep venous thrombosis, although this has not been proven. Other proponents state the pain control aspect of the nerve block is superior to intravenous and oral opioid medications. In a recent article in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery by Chang et al, perioperative pain levels were assessed for 424 patients undergoing TKA. The methods of managing pain, the combined use of peri-articular infiltration and nerve blocks provided better pain relief than other methods during the first two post-operative days. Patients managed with peri-articular injection plus nerve block, and epidural analgesia was more likely to have higher satisfaction at two weeks after TKA.22 However, femoral nerve blocks are not free from risk. One multicenter study followed 709 patients after a femoral nerve block before TKA. They found that 12 patients sustained falls postoperatively, likely secondary to quadriceps weakness; five patients had postoperative femoral neuritis and one patient had new onset atrial fibrillation.23

In our study, patients who received a femoral nerve block reported decreased pain on postoperative days one and two and received less pain medication overall than those patients who did not receive a femoral block. There were no complications from the nerve block in our particular set of patients. These results correlate with the previously explained published data.

4.5. ON-Q continuous pain pump

Perhaps the most significant finding in this study was the adverse effects of the ON-Q pump on TKA rehabilitation and recovery. The ON-Q Pain Relief System is a trade marked brand name non-narcotic pump that automatically and continuously delivers a regulated flow of local anesthetic to a patient’s surgical site or in close proximity to nerves providing targeted pain relief for up to five days.24 Although this sounds promising, multiple studies have been published that prove nerve blocks are superior to continuous local anesthesia in pain control. Cip et al published an article in the Journal of Anesthesia recently and states that those patients who underwent continuous local anesthesia after TKA showed higher pain intensity levels and showed significantly higher postoperative opioid consumption.25

The data from this study demonstrated that those patients who received the ON-Q pain pump after TKA ambulated on average 45 feet less on postoperative day one than those patients who did not receive the ON-Q pump. These results could be related to the fact that those patients with an ON-Q pump had increased numbness and anesthesia of their operative joint and therefore decreased proprioception. Although not proven, this inhibited proprioception may have led to the decreased ambulation.

Furthermore, there was a statistically significant (p value 0.001) increase in length of stay (LOS) in the hospital from 2.81 days without an ON-Q pump to an average of 3.50 days with the ON-Q pump (Fig. 2). That’s an average increase in hospital stay by one day. The increased length of stay can lead to multiple negative effects on a patient’s recovery from TKA. For example, one major risk factor that can occur as a direct result in increased LOS is Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Inpatient LOS has been shown to be significantly longer at hospitals with greater CDI incidence at both the hospital and individual level. At a hospital level, a percentage point increase in the CDI incidence rate is associated with more than an additional one day stay (between 1.19 and 1.61 days).26

Fig. 2.

Length of stay with and without On-Q.

In addition to the increased risk of infection to the patient, is the increased cost to healthcare system as a whole with increased LOS after surgery. The reimbursement methodology for total hip and knee replacements is partially based on the length of stay (LOS) for these patients. The average length of stay for total hip and total knee replacements has continued to decrease over the years as anesthesia procedures, surgical techniques, pain management protocols, implant advancements and hospital processes have improved.27 Medicare front-loads the reimbursement to cover the higher cost of the first day of hospitalization with the remainder of the payment dispersed throughout the hospital stay. Hospitals that have a lower LOS without readmission will be better positioned to maximize their reimbursement while controlling their costs of additional bed days.27

In 2013, Medicare allocated $6975 reimbursement for day one since this is where a majority of the costs lie (day of surgery and implant cost). The payment allocation is $3488 for day two and $698 for day three. The average bed day costs allocated by a hospitalare generally $500–$700 per day. In 2013, the average LOS was 3.2 days, and the Medicare reimbursement for day three would roughly equal the bed day cost. However, with the decrease in average LOS in 2014 to 3.1 days, the payment for day three has decreased to $370. Based on the bed day costs, most hospitals would incur a financial loss on the third day (Fig. 3).

This data proves that those patients in our study who receive an On-Q pump and are staying in the hospital an average of 3.50 days are not only lacking in their rehabilitation process, they are actually costing the hospital and the surgeons reimbursement. By postoperative day 3, the hospital actually has to pay an average of $350 for the patient that remains in house after TKA.

5. Conclusion

Postoperative pain control modalities after TKA are highly variable among physicians. This variability has allowed researchers to look at each modality and compare and contrast the benefits with the potential harmful effects of these medications on TKA outcomes. The data in this study suggests that the use of Valium causes a need for more pain medication and decreased patient satisfaction. It also demonstrates that patients who underwent preoperative nerve blocks had decreased pain on postoperative day one and greater patient satisfaction. However, the most notable contribution of this study was the negative effects of the continuous pain pump, ON-Q. The patients who were treated with this modality had decreased ambulation on postoperative day one and on average stayed in the hospital one extra day, a variable that significantly increases the cost of a TKA for the hospital, the surgeon and the patient. Even though this data is significant, further studies should be performed enhance our knowledge of postoperative pain control for these patients.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest with this article and the following authors did not receive any funds from vendors Steve O’Neil, DO, Kristopher Danielson, DO, Kory Johnson, DO, Thomas Matelic, MD.

References

- 1.AAOS; 2018. A Nation in Motion. Total Knee Replacement Surgery by the Numbers. Anationinmotion.org. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filos K.S., Lehmann K.A. Current concepts and practice in postoperative pain management: need for a change? Eur Surg Res. 1999;31:97–107. doi: 10.1159/000008627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Follin S.L., Charland S.L. Acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:1068–1076. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sriwatanakul K., Weis O.F., Alloza J.L., Kelvie W., Weintraub M., Lasagna L. Analysis of narcotic analgesic usage in the treatment of postoperative pain. JAMA. 1983;250:926–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warfield C.A., Kahn C.H. Acute pain management. Programs in U.S. hospitals and experiences and attitudes among U.S. adults. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:1090–1094. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199511000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apfelbaum J.L., Chen C., Mehta S.S., Gan T.J. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:534–540. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068822.10113.9E. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung F., Ritchie E., Su J. Postoperative pain in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:808–816. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawal N., Hylander J., Nydahl P.A., Olofsson I., Gupta A. Survey of postoperative analgesia following ambulatory surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:1017–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parvizi J., Porat M., Gandhi K., Viscusi E.R., Rothman R.H. Postoperative pain management techniques in hip and knee arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 2009;58:769–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maheshwari A.V., Blum Y.C., Shekhar L., Ranawat A.S., Ranawat C.S. Multimodal pain management after total hip and knee arthroplasty at the Ranawat Orthopaedic Center. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1418–1423. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0728-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parvataneni H.K., Ranawat A.S., Ranawat C.S. The use of local periarticular injections in the management of postoperative pain after total hip and knee replacement: a multimodal approach. Instr Course Lect. 2007;56:125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinatra R.S., Torres J., Bustos A.M. Pain management after major orthopaedic surgery: current strategies and new concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:117–129. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wisner D.H. A stepwise logistic regression analysis of factors affecting morbidity and mortality after thoracic trauma: effect of epidural analgesia. J Trauma. 1990;30:799–804. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wattwil M. Postoperative pain relief and gastrointestinal motility. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1989;550:140–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr D.B., Goudas L.C. Acute pain. Lancet. 1999;353:2051–2058. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samad T.A., Moore K.A., Sapirstein A., Billet S., Allchorne A., Poole S., Bonventre J.V., Woolf C.J. Interleukin-1beta-mediated induction of Cox-2 in the CNS contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. Nature. 2001;410:471–475. doi: 10.1038/35068566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moucha, Calin S., Weiser, Mitchell C., Levin Emily. Current strategies in anesthesia and analgesia for total knee arthroplasty. JAAOS. 2016;(March) doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melchior Maggane, Pierrick Poisbeau, Isabelle Gaumond, Serge Marchand. Insights into the mechanisms and the emergence of sex differences in pain. J Neurosci. 2016;338:63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.05.007. Copyright 2017 IBRO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou Roger, Gordon Debra B., de Leon-Casasola Oscar A., Rosenberg Jack M., Bickler Stephen, Brennan Tim. American pain society. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. Copyright @2016 American Pain Society. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valium. Drugs.com. Copyright 1996–2017 Cerner Multum Inc. Version 13.03. Revision date 09-28-16.

- 21.Jones J.D., Mogali S., Comer S.D. Polydrug abuse. A review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1):8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.004. Copyright 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang C.B., Cho W.S. Pain management protocols: perioperative pain and patient satisfaction after total knee replacement: a multicenter study. JBJS. 2012;94(11):1511–1516. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B11.29165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma Sanjeev, Iorio Richard, Specht Lawrence M., Davies-Lepie Sara, Healy William L. Complications of femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(January (1)):135–140. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1025-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.What is On-Q? MyOn-Q.com.

- 25.Cip Johannes, Erb-Linzmeier Hedwig, Stadlbauer Peter, Bach Christian, Martin Arno, Germann Reinhard. Continuous intra-articular local anesthetic drug instillation versus discontinuous sciatic nerve block after total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.08.027. Copyright 2016 Elsevier Inc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller A.C., Polgreen L.A. Hospital clostridium difficile infection rates and prediction of length of stay in patients without C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(4):404–410. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Accelero Health Partners . 2018. Length of Stay is Critical to Total Hip and Knee Replacement Cost of Care. AcceleroHealth.com. [Google Scholar]