Abstract

Social network users often see their online friends post about experiential purchases (such as traveling experiences) and material purchases (such as newly purchased gadgets). Three studies (total N = 798) were conducted to investigate which type of purchase triggers more envy on Social Network Sites (SNSs) and explored its underlying mechanism. We consistently found that experiential purchases triggered more envy than material purchases did. This effect existed when people looked at instances at their own Facebook News Feeds (Study 1), in a controlled scenario experiment (Study 2), and in a general survey (Study 3). Study 1 and 2 confirmed that experiential purchases increased envy because they were more self-relevant than material purchases. In addition, we found (in Study 1 and 3) that people shared their experiential purchases more frequently than material purchases on Facebook. So why do people often share experiential purchases that are likely to elicit envy in others? One answer provided in Study 3 is that people actually think that material purchases will trigger more envy. This paper provides insight into how browsing SNSs can lead to envy. It contributes to the research on experiential vs. material purchases and the emotion of envy.

Keywords: Experiential purchases, Material purchases, Envy, Social comparison, Social network sites

Highlights

-

•

Users report that experiential purchases trigger more envy than material purchases.

-

•

This is because experiential purchases are more self-relevant to most Facebook users.

-

•

Experiential purchases are shared more frequently than material purchases.

-

•

Readers prefer to see other's experiential purchases more than material purchases.

-

•

Posters wrongly think material purchases should trigger the most envy.

1. Introduction and theoretical background

Social network users often share positive news such as their traveling experiences or newly purchased gadgets. Others, who read such posts, may compare themselves unfavorably with the poster (Festinger, 1954), which could lead to the unpleasant feeling of envy (Smith & Kim, 2007). Krasnova, Wenninger, Widjaja, and Buxmann (2013) identified several content categories that often trigger envy on Facebook, including categories such as travel and leisure, money and material possessions, achievements in job and school, relationship and family, and appearance. The first two categories resemble the distinction between experiential and material purchases (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003, p. 1194), the effects of which are widely investigated in the consumer psychology literature. The current research mainly investigates which type of content (experiential vs. material purchases) on Social Network Sites (SNSs) triggers more envy and why this is the case.

In the following parts, we will first introduce the concept of envy and address why it is so relevant to study envy on SNSs. We then introduce the distinction between experiential and material purchases, and explain why it is important to test whether experiential or material purchases trigger more envy.

1.1. Envy and SNSs

Envy is the emotion that “arises when a person lacks another's superior quality, achievement, or possession and either desires it or wishes that the other lacked it” (Parrott & Smith, 1993). The concept of envy involves two parties: the envier (who is in the inferior position) and the envied person (who possesses the envied object). The emotion envy has important consequences. First, envy feels negative and contains feelings of frustration (Smith & Kim, 2007). Second, feeling envious can be detrimental for the relationship with the envied person, as envy can lead to negative behavior towards the person being envied (such as gossiping, Wert & Salovey, 2004).

At the same time, envy can also have more positive consequences, as it can motivate people to improve their own position (Van de Ven, Zeelenberg, & Pieters, 2011b) and stimulate consumption (Crusius & Mussweiler, 2012; Van de Ven, Zeelenberg, & Pieters, 2011a). Therefore, knowing which type of content on SNSs triggers more envy (and why this is the case) can help social media marketers to utilize this emotion for better advertising.

The current manuscript focuses on the emotion of general envy as a result of SNS consumption. People who share their fabulous new purchases online can trigger envy in others. Indeed, researchers found that passive consumption of SNSs leads to more envy, and this envy in turn decreases life satisfaction and well-being (Appel, Crusius, & Gerlach, 2015; Krasnova, Widjaja, Buxmann, Wenninger, & Benbasat, 2015; Steers, Wickham, & Acitelli, 2014; Tandoc, Ferrucci, & Duffy, 2015; Verduyn, Ybarra, Résibois, Jonides, & Kross, 2017). Given these negative effects of envy on well-being, gaining a better understanding of the causes of envy on SNSs is important. Furthermore, experiencing envy while browsing SNSs also increases the likelihood that someone leaves the SNS platform (Lim & Yang, 2015). As a result, users may stop using the current social network service when too much envy is triggered. It is therefore important for SNS providers to know under which conditions the general negative emotion of envy is likely to be triggered.

1.2. Experiential vs. material purchases

We think the distinction between experiential and material purchases can help identify when people are most likely to become envious on SNSs. The distinction between experiential and material purchases was first proposed by Van Boven and Gilovich (2003): Experiential purchases are “those made with the primary intention of acquiring a life experience: an event or series of events that one lives through”, and material purchases are “those made with primary intention of acquiring a material good: a tangible object that is kept in one's possession”. The main difference between experiential and material purchases lies in the intention of the purchase: to do vs. to have (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003). This distinction between purchase types has turned out to be fruitful in spurring new research questions and understanding the consumer experience.

Previous research on these purchase types mainly focused on investigating which type of purchase brings more happiness, and the results showed that spending money on experiential purchases typically brings more happiness (Gilovich, Kumar, & Jampol, 2015). Three underlying mechanisms for why experiences tend to bring more happiness were summarized by Gilovich et al. (2015). First, experiential purchases enhance social relations more than material purchases do, and thereby improving well-being (Caprariello & Reis, 2013; Kumar & Gilovich, 2015). Second, experiential purchases tend to be more closely associated with one's central identity than material purchases are, acquiring them is therefore likely to have a stronger positive effect on well-being (Carter & Gilovich, 2012). Lastly, experiential purchases are more unique and difficult to be compared with, hence they trigger less social comparisons than material purchases do (Carter & Gilovich, 2010). In the next two sections, we will first introduce some relevant work on envy and then explain why these mechanisms for happiness are also important when studying the effects of purchase types on envy.

1.3. The relation between envy and experiential/material purchases

To the best of our knowledge, there are three studies that tested differences in felt envy over experiential and material purchases. However, these do not yet paint a clear picture on the effects of these purchase types on envy. First, Krasnova et al. (2015) found that people indicated that, from all instances of envy reported, a category posts about travel and leisure was the category that elicited envy on Facebook the most frequently (62.1%); and people were rarely envious about “material possessions” on Facebook (5.9%). This finding, that people report being envious about experiences more frequently than about material objects, could have two causes: 1) experiences are shared more often and are therefore more likely to be a cause of envy (higher base rate), or 2) each instance of a shared experience is more likely to trigger envy than a shared material purchase is. Therefore, the current studies will 1) test if experiential purchases are posted more frequently on SNSs than material purchases (and with more posts in that category, the chance that one triggers envy becomes higher); and 2) test the envy intensity while controlling for the exposure frequency (to see whether experiential or material purchases are likely to elicit more intense envy).

Besides this work of Krasnova et al. (2015), there appear to be two conflicting findings in the literature: Carter and Gilovich (2010, Study 5c) found that jealousy (used in their study to measure envy) was stronger towards someone else who had a better laptop than the participant, compared with the situation in which someone had a better vacation than the participant. This was thought to be due to the idea that material purchases are more comparative than experiential purchases, as the value of an experiential purchase is usually hard to estimate. This would thus lead to the prediction that, in general, sharing a material purchase would be more likely to elicit envy than sharing an experiential purchase would. However, Lin and Utz (2015, in Study 2) found that envy was stronger when they saw a Facebook friend post a picture of a vacation, than when they saw the same person post a picture of a newly bought iPhone. This would suggest that experiential purchases might trigger more envy. These seemingly conflicting results make it important to test whether it is experiential or material purchases that elicit a higher degree of envy (and why they do so).

1.4. Hypotheses

1.4.1. Which type of purchase is shared more frequently, and why?

As mentioned above, one mechanism that explains why experiential purchases trigger more happiness is about the social and hedonic value of sharing experiential purchases. Kumar and Gilovich (2015) asserted people tend to talk more about their experiential purchases than material purchases. This is because of three reasons. First, it is more rewarding to talk about one's experiential purchases than material purchases as it helps to build social capital. Van Boven, Campbell, and Gilovich (2010) showed that due to the stigmatization of materialism, others enjoy the conversation and the person more when talking over experiential purchases than material purchases. Second, by talking to others, people can re-live experiences after the experiences have happened (Kumar & Gilovich, 2015). Third, people may even re-create the experience and add a “rosy view” by talking about them (Kumar & Gilovich, 2015). Therefore, more satisfaction and happiness are gained by talking about experiential purchases than material purchases. Based on these reasons, we expected that.

H1

Social network users are more likely to post about their experiential purchases than material purchases.

Note that this would imply that even if material and experiential purchases trigger similar levels of envy in intensity, the more frequent sharing of experiential purchases would suggest that these experiences trigger envy more frequently.

Which type of purchase triggers more intense envy, and why?

For the question which type of purchase triggers stronger envy (in intensity), it is still unclear given the contradicting earlier findings. Note that there are also two different possible mechanisms (self-relevance vs. comparability) based on the theory of experiential vs material purchases, that would lead to different predictions about which one is more likely to trigger envy.

Self-relevance. Experiential purchases tend to be more central to one's self-identity compared with material purchases (Carter & Gilovich, 2012). When people look back on their life, they indicate that experiences were more important parts of their life than material purchases were (Kumar, Mann, & Gilovich, 2017). Self-relevance of the comparison domain is also a key antecedent of envy according to social comparison theory: Things that are more important to you and are seen as a larger part of your identity are more likely to trigger envy (DeSteno & Salovey, 1996; Festinger, 1954; Salovey & Rodin, 1984). This is the main reason why it could be predicted that experiences are more likely to trigger envy than material purchases do: When others showcase their experiential purchases, and these experiences are also more likely to be self-relevant and important to those observing the posts, more intense envy is likely for such experiential purchases over material ones. Hence.

H2

a) Experiential purchases are typically more likely to be self-relevant to people than material purchases are, which b) makes experiential purchases trigger more envy than material purchases.

Comparability. The second important point relates to the comparability of material and experiential purchases. Gilovich et al. (2015) explained that experiential purchases are evaluated more on their own terms and that they evoke less social comparisons. A concrete product is relatively easy to compare, but an experience (e.g., a vacation) is typically unique and difficult to compare. Carter and Gilovich (2010) found that for material purchases people are more sensitive to how aspects of one's own purchase relate to possible alternatives. As an upward social comparison is the key cause of envy (Smith & Kim, 2007), the findings that material purchases are easier to compare suggests that they likely trigger envy more easily as well. Therefore.

H3

a) People make comparisons more easily for material purchases than for experiential purchases, which b) makes material purchase trigger more envy than experiential purchases.

1.5. Current research

To summarize, we will first examine which type of purchase are shared more frequently on SNSs. This will replicate earlier work of Kumar and Gilovich (2015) that people are more likely to share experiences than material purchases, but also that of Krasnova et al. (2015) that posts on SNSs about leisure (i.e. experiences in our terms) are shared more often than about material possessions.

We also examine which type of content (experiential vs. material purchase) triggers more intense envy on SNSs and explore the underlying mechanism (self-relevance vs. comparability). Two conflicting findings exist in the earlier research: Lin and Utz (2015) found that experiential purchases triggered a higher degree of envy, while Carter and Gilovich (2010) found that material purchases triggered a higher degree of envy. We also add theoretically derived mechanisms, which can help explain why a possible difference occurs in the envy that is elicited by experiential or material purchases.

Three studies are designed to test these hypotheses. Study 1 uses more naturalistic observations in which participants report on an experiential and a material purchase from their own Facebook friends, and measure resulting envy. Study 2 uses a more controlled experimental scenario study based on past work on experiential purchases vs. material purchases to see which of two similarly priced purchases would trigger more envy. Finally, Study 3 will examine these research questions via a survey method from two perspectives: those who post themselves vs. who read what someone else's posts. It examines which type of purchase triggers most envy when reading such a post. It also tests if posters are accurate in predicting which type of posts is most likely to elicit envy in others. Studies 1 to 3 thus all allow us to test whether it is experiential or material purchases that trigger more intense envy. Studies 1 and 2 also focus on the mechanism why it is experiential or material purchases that trigger more intense envy. Finally, Studies 1 and 3 also measure how frequent people encounter experiential and material purchases on SNS, to see which has the potential to trigger envy more frequently.

2. Study 1

Study 1 is a lab study with a within-subject design. It examines which type of purchase (experiential vs. material) triggers more envy by asking people to look at real posts from their own News Feed. The platform of Facebook is used, as it is one of the most popular SNS worldwide. Facebook users were asked to look at their own News Feed to report the first instance in which a friend shared an experiential and a material purchase. They were also asked to report how frequent they see posts in each category. For each reported post, we measured how important the shared topic was for their own identity (self-relevance), how easy it was to compare the shared purchase to other possible purchases (comparability), and how intense the envy is. It was then tested whether self-relevance and comparability mediated the effect of product type on envy. In addition to the degree of envy, this set-up allowed to test if Facebook users are more likely to be exposed to posts from friends about experiential purchases than material purchases (exposure frequency).

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Procedure

Participants were recruited via a Dutch University local panel. Our study was part of a series of independent studies, that together lasted 50–60 min and participants were paid 8 Euro for their participation. Participants completed an online questionnaire in Dutch. They were asked to search through their Facebook News Updates, and, if possible, report the first post they see about an experiential purchase by their Facebook Friends and the first post about a material purchase. The two post categories were identified as following: 1) a post of an experiential purchase mainly addresses a (paid) experience (e.g., a dinner, party, holiday or vacation, concert, etc.) of a Facebook friend; 2) a post about a material purchase mainly addresses a purchased product (e.g., a car, telephone, television, clothes, etc.) of a Facebook friend. They were asked to continue with the survey once they found the two posts: one post for each category. If they had not found these within 10 min, the survey gave off a signal and they were asked to continue as well. Participants were asked to first describe the post(s) that they had found, then answer several questions for each of the reported posts, and fill out demographic information (age, gender, education). For exploratory purposes, several additional questions had been added. For a full list of these questions (and the results), please see Appendix A.

2.1.2. Measures

Participants indicated whether they had found a post in each category (experiential and material purchase) and briefly wrote down what the post was about.

Frequency of exposure to experiential and material purchases. Participants were asked to report how often they see posts from their Facebook Friends about experiential and material purchases respectively in the past year. Answers were rated with a 7-point ordinal scale from never (1), (via less than once a month, once a month, 2–3 times a month, once a week, 2–3 times a week) to daily (7).

Degree of envy (intensity). After each reported post, participants were asked to indicate to what extent they felt envy after reading the reported post by using the three items: “I felt a little frustrated that the other was better off than I”, “I was a bit envious”, and “I was a bit jealous”, rated continuously with a slider scale from not at all (0) to very much so (6), (Cronbach's α = 0.77 for experiential category, and Cronbach's α = 0.88 for material category). These three items were adapted from the envy scale used by van de Ven (2017).

Underlying mechanisms. Self-relevance was measured by the following question: “To what extent is the thing acquired by the other person important to you (in other words, is the domain in which the other bought something also important to you)?”, using a continuous slider scale from not at all (0) to very much so (9). Comparative nature of the envied object (comparability) was measured with one item: “It was about something that is easy to compare with what someone else can buy”. Participants were asked to rate it from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

Manipulation check (type of post). We examined whether the reported post indeed belonged to each category by asking whether it was seen as something material or experiential. It was asked “to what extent do you think the purchase in the Facebook post is an experience (something you buy to do), or a material possession (a product you buy to have/use)?”. Participants rated each reported post with a scale from definitely experience (−4) to definitely material possession (4).

Sample. Of the 178 participants who eventually came to the lab and completed the questionnaire, 6 did not have a Facebook account and were excluded (Mage = 21.48, SDage = 3.12, 68% female). Participants in this sample visited Facebook on average one to several times a day, read their news feeds one to several times a day, and posted status updates once a month. They spent on average about 1–2 h on Facebook in the past week, and the average amount of Facebook Friends was 434, SD = 245, median = 400.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Frequency of exposure to experiential and material purchases

Among 172 Facebook users, 131 participants found both types of posts, 39 participants found only a post of experiential purchase, and 2 participants found only a post of material purchase. This suggests that posts about both experiential and material purchases are quite common, but that posts about experiential purchases were encountered more frequently (McNemar's χ2(1) = 31.61, p < .001). In total, 98.8% of participants encountered at least one post about an experiential purchase within 10 min of scrolling through their News Feed, 77.2% encountered at least one about material purchases.

For how often people in general see posts about experiential or material purchases, we found that participants reported that in the past year they have seen more experiential posts (M = 5.72, SD = 1.39) than material posts (M = 4.28, SD = 1.55), t(171) = 12.97, p < .001, dz = 0.99, which is in line with the prediction of H1. Participants in this sample saw experiential posts on average two to three times per week, whereas they saw material posts on average two to three times per month.

2.2.2. Type of posts, envy, self-relevance, and comparability

In order to compare how someone responds to experiential and material purchases, we only take the participants who have reported both an experiential and a material post. The reason is that we cannot do the within-subject comparisons for those who found only one post, and treating responses to experiential and material posts as independent would ignore the existing dependency. The sample size is thus 131 participants when looking at the effect of reading a material or experiential post on envy (as well as the possible reasons for why they envy). Table 1 contains the descriptive statistics for each type of post and the statistical tests comparing the responses. Table 2 contains the correlations between the variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and the results of within-subject comparisons in Study 1.

| Experiential |

Material |

Statistics |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | n | t | p | |

| Experiential (−4) to Material (+4) | −1.95 | (2.42) | 1.49 | (2.42) | 129 | −11.26 | <.001 |

| Envy (0–6) | 0.85 | (0.98) | 0.67 | (1.07) | 130 | 1.83 | .070 |

| Self-relevance (0–9) | 3.90 | (2.71) | 2.88 | (2.70) | 131 | 3.43 | <.001 |

| Comparability (1–7) | 4.82 | (1.56) | 5.08 | (1.75) | 131 | −1.35 | .179 |

Table 2.

Pairwise correlations for experiential/material conditions respectively in Study 1.

| Pearson's Correlations | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Envy (0–6) | 1 | ||

| 2. Experiential (−4) to Material (+4) manipulation check | −.01/−.04 | 1 | |

| 3. Self-relevance (0–9) | .40∗∗∗/.39∗∗∗ | −.12/.04 | 1 |

| 4. Comparability (1–7) | .00/−.05 | .15/.33∗∗∗ | .02/.24∗∗ |

∗p < .05; ∗∗p < .01; ∗∗∗p < .001.

As can be seen in Table 1, the manipulation check showed that participants reported posts in the material condition as more material than those in experiential condition, t(128) = −11.26, p < .001, dz = 0.99. With regard to envy intensity, participants reported a marginally significant higher level of envy when they read the reported experiential post than the reported material post, t(129) = 1.83, p = .070, dz = 0.16. These results are a first indication that experiential posts likely triggered more envy on Facebook, showing initial support for H2b and they reject H3b.

As Table 1 shows, the results also supported H2a: Self-relevance, the perception that the purchase of the other was also important for oneself, was higher in the experiential condition than in the material condition, t(130) = 3.43, p < .001, dz = 0.30. With regard to H3a, the comparability of experiential purchases was slightly lower than that of material purchases, but the effect was not significant, t(130) = −1.35, p = .179, dz = 0.12.

The correlational statistics (see Table 2) revealed that the degree of envy was highly correlated with self-relevance, but not with comparability. We had expected that the difference in envy elicited by experiential and material purchases to be mediated by the perceived self-relevance of the situation and comparability as well. As the design was within-subjects, we used Judd, Kenny, & McLelland (2001) method to examine mediation (using bootstrapping). The first step in a within-subjects mediation analysis was to test whether there is a condition effect (a difference between material and experiential posts) on the dependent variable (envy) and the possible mediators (self-relevance and comparability). As Table 1 shows, all these three effects of the condition were at least marginally significant. Second, the within-subjects difference score for the effect of condition on the mediator should predict the condition difference score on the dependent variable (e.g., the increased self-relevance for experiential purchases over material purchases should predict the increase in envy for experiential purchases over material purchases). The result of the bootstrapping regression model showed that self-relevance played a mediating role in explaining why envy differed across two conditions: Based on 5000 bootstrap samples, the bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect of the type of post on envy via self-relevance did not include zero (0.28–0.58). The 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect via comparability did include zero (−0.31 to 0.10), indicating no mediating role of comparability (because changes in comparability turned out to not be associated with changes in envy in this study).

2.3. Discussion

In this study, we examined whether reading posts about experiential purchases or material purchases triggers more envy. The results are a first indication that seeing a Facebook friend post about an experiential purchase triggers more intense envy than seeing a Facebook friend post about a material purchase. For the potential mechanisms, we examined the role of self-relevance and the comparative nature of envied object. We replicated earlier work that posts about experiential purchases were seen as more self-relevant (Gilovich et al., 2015). There was no significant effect that material purchases were easier to be compared with each other, but the direction of the effect was in line with the findings of Carter and Gilovich (2010). Nevertheless, only self-relevance was related to envy in this case: The higher envy for experiential purchases existed (for a part) because these were seen as more self-relevant, supporting H2 and rejecting H3.

Another finding is that, in line with H1, users encounter posts about experiential purchases much more frequently on SNSs. This is also one reason to explain why experiential purchases are more likely to elicit envy than material purchases (Krasnova et al., 2015): Typical posts about experiences trigger more intense envy than posts about material purchases, but people also encounter the posts about experiential purchases more frequently probably giving rise to more frequent envy as well.

This study had the advantage that it used people's responses to actual posts on their News Feeds. Furthermore, it used a within-subjects design that allowed the comparison of responses to experiential versus material posts of the same person. One limitation of Study 1 is that the price/size of the envied object and the perceived similarity to the poster seem to be unequal across the two comparison groups (see the additional results in Appendix A). Nevertheless, the post-hoc analysis showed that, even when controlling for the perceived similarity to the poster and the size/price of the envied object, self-relevance was still an important mediator (95% CI; 0.22 to 0.51). Study 2 was further conducted to exclude the influence of these factors.

3. Study 2

Study 2 was an online experiment aimed to again test whether a shared experiential purchase triggers more envy or a shared material purchase does. In Study 2 we controlled for the price of the envied object and the poster. The study stimuli were developed based on the previous work on material and experiential purchases (see Study 2, Rosenzweig & Gilovich, 2012). Following their study, we created two hypothetical Facebook posts, one in which a person displayed a recently bought iPod and the other in which the same person displayed a visit to a music venue, both labeled as having the same price ($55). This has the advantage that both the material and experiential purchases are in the same domain (music) and have the same price.

Besides measuring how much envy the purchase elicited, we also measured self-relevance of the purchase and the comparability of the product to what one has oneself. Finally, this study also adds a third important consequence that differs between experiential and material purchases, which is whether someone likes the other person more after seeing his/her post about the purchase. In their review on the differences between material and experiential purchases, Gilovich et al. (2015) concluded that experiential purchases improve social bonds. Therefore, we hypothesized that sharing posts about experiential purchases is more likely to increase liking than sharing material purchases is. This might be the reason why users are more likely to share experiential purchases than material purchases on Facebook, even if readers might become more envious when the former are being shared.

3.1. Method

A one-minute online questionnaire was conducted with a one-way (type of purchase: experiential vs. material) between-subjects design. Two hundred and fifty-two Amazon mTurk workers completed the questionnaire, and each of them was paid $0.15. Participants were instructed to imagine that they encountered a Facebook post made by someone they know (called “Joe”). Participants were randomly assigned to the experiential condition and saw a post by Joe about having bought a concert ticket worth 55$. The other participants were assigned to the material condition and saw a post by Joe having bought an iPod shuffle also priced at 55$. The exact posts can be found in Appendix B.

In both conditions participants were asked to evaluate their degree of envy by answering “Would you be a little envious of Joe?”. Self-relevance was measured with one item: “How important is it for you to have a similar thing as the one Joe posted about?”. Comparability was measured with “Did Joe's post make you think about what you have yourself and how that relates to what Joe has?”. These questions were all answered on a continuous slider scale from 0 (not at all) to 6 (very much so). Additionally, we asked “does Joe's post make you like him less or more” for the changed level of liking. Participants rated this question on a slider scale from −3 (like him much less) to 3 (like him much more). The sequence of these four measurements was randomized. At the end of the questionnaire, demographic information (gender, age, and whether the participant is a Facebook user) was measured.

After excluding 9 participants who had no Facebook account and 2 participant who did not complete the full questionnaire, the final sample included 241 participants (Mage = 32.35, SDage = 9.82, 39% female).

3.2. Results and discussion

Table 3 depicts the mean values per condition for each measured variables and the results of between-group comparisons. As can be seen in Table 3, participants reported more envy (t(239) = 6.04, p < .001, d = 0.78) and a higher degree of self-relevance (t(239) = 3.05, p = .003, d = 0.37) in the experiential condition than in the material condition. There was no difference in the comparability across two conditions, t(239) = 0.80, p = .421. Once again, H2 was supported but H3 was rejected. In addition, we found that participants liked someone who posted about an experiential purchase more than someone who posted about the material purchase, t(239) = 4.83, p < .001, d = 0.63. A closer examination shows that when someone shares an experiential purchase, participants liked that person more than they did before, t(123) = 2.88, p = .005, d = 0.26 (compared with the neutral point of the scale). When someone posts a material purchase, participants indicated they would like the person less than before, t(116) = −3.89, p < .001, d = 0.36 (compared with the neutral point).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and the results of between-group comparisons in Study 2.

| Experiential (n = 124) |

Material (n = 117) |

Independent t-Tests |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | t | p | |

| Envy (0–6) | 2.08 | (1.81) | 0.86 | (1.24) | 6.04 | <0.001 |

| Self-relevance (0–6) | 1.34 | (1.50) | 0.82 | (1.08) | 3.05 | 0.002 |

| Comparability (0–6) | 1.95 | (1.64) | 1.78 | (1.65) | 0.80 | 0.421 |

| Liking (−3 - 3) | 0.24 | (0.93) | −0.37 | (1.02) | 4.83 | <0.001 |

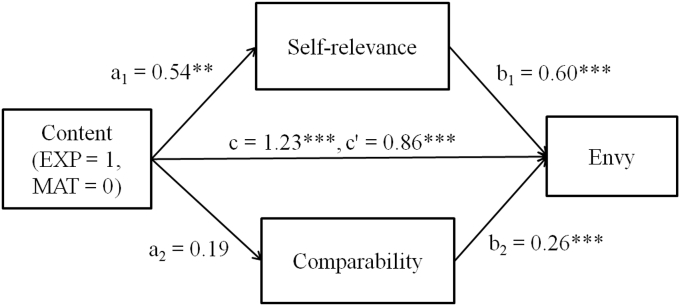

A mediation analysis was conducted to test the mediating role of self-relevance and comparability using ordinary least squares path analysis in PROCESS (Hayes, 2013) (see results in Fig. 1). A bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect of self-relevance (a1b1 = 0.33) based on 5000 bootstrap samples was entirely above zero (0.14–0.57), but the confidence interval for indirect effect of comparability (a2b2 = 0.05) included zero (−0.05 to 0.20). In other words, the experiential purchases triggered a higher degree of envy, for a part because it was more self-relevant. In this study, we did find that comparability of the product increased envy (similar to what we found in Study 1). This time the manipulation of the type of product (experiential versus material) did not affect perceived comparability. Because of this, there was also no indirect effect of product type on envy via comparability.

Fig. 1.

Mediating Model in Study 2 (Unstandardized Regression Coefficients; ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .001.).

To summarize, we replicated that an experiential purchase triggered more envy than a material purchase did. Consistent with Study 1, we found again that this effect arises for a part because the experiential purchase was seen as more self-relevant. Just like in Study 1, we found no mediation of comparability; but this time there was an effect of comparability on envy (but no effect of the condition on comparability). This might be due to the slightly changed measure of comparability: In Study 1, we measured comparability with the comparative nature of the envied object (i.e., “whether the object itself is something that everyone thinks it is easy to compare with”); but in Study 2, we measured comparability by addressing comparing one's current situation with the poster. This change was made due to the specific context of the study design. This change of measure is a limitation of the current study, and future research should try to replicate the findings by developing reliable and consistent measurement for comparability. However, another reason for the lack of an effect on comparability is that in this study the price of the product was mentioned explicitly and held constant across conditions, leading to identical means of comparability (probably also with an alternative measure).

Interestingly, although the experiential purchases do trigger more negative feelings in the form of envy, people do actually like someone more who posts about an experiential purchase. This is also in line with Van Boven et al.’s (2010) finding that others enjoy a conversation about experiential purchases more than one about material purchases. It seems that most social network users are somehow aware of the social norm that sharing experiential purchases is in a more positive light than sharing about material purchases, and therefore share experiential purchases more often. Interestingly, this does also increase the chance of triggering the negative experience of envy in others. This issue is investigated in Study 3 both a poster's and a reader's perspective.

4. Study 3

Studies 1 and 2 found that posts about experiential purchases elicit a higher degree of envy in those reading the posts (compared with posts about material purchases). However, we also know that people do not like to be envied by others (Foster et al., 1972; Rodriguez Mosquera, Parrott, & Hurtado de Mendoza, 2010; Van de Ven, Zeelenberg, & Pieters, 2010). Indeed, people feel discomfort when they receive preferential treatment over others (Jiang, Hoegg, & Dahl, 2013) and can feel guilty or anxious when others are thought to be envious of them (Romani, Grappi, & Bagozzi, 2016).

How do we reconcile that people share these envy eliciting stories if they do not like to be envied? Study 2 already provided one answer: Despite the increase in envy, people do like those who share experiential purchases more. Study 3 tested a second possible reason, namely that people wrongly predict what will elicit envy in others. Do they actually realize that others will become more envious over experiential purchases than over material purchases?

In addition to the original hypotheses, in Study 3, we explored the degrees of envy triggered by five categories of posts (i.e., experiential purchases, material purchases, relationships, achievements, and appearances) and from two different perspectives: the poster's (the person who posted the post) and the reader's (the person who read the post). These categories were found by Krasnova et al. (2013) to be the most common categories of posts that may trigger envy on Facebook. Including more post categories than only experiential and material purchases made the study broader, and allowed us to explore how purchases trigger envy in relation to other possible topics people might share. In addition, we expected that there would be a prediction error: People who post a topic (posters) would think that posts about material purchases would elicit most envy, while readers actually experience more envy when seeing posts about experiential products.

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Procedure

Participants were recruited via Amazon MTurk for a 10–15-min survey that paid $1.50. They were required to be active social network users (who used Facebook at least weekly), at least 18 years old, and located in the U.S. Five post categories were examined: experiential purchases, material purchases, relationships, achievements, and appearances. The description that described each post category can be found in Appendix C. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions: Participants were asked to answer questions with regard to each of the five post categories from either a poster's (n = 188) or a reader's (n = 197) perspective. In other words, participants in the poster's version were asked to imagine how others would react to participants' own posts, and participants in reader's version were asked to report their reaction after reading the posts made by others.

We first asked how frequently people typically posted items from each category themselves (in the poster's version) or how much they liked to see posts from each category (in the reader's version). Then, for each post category, we measured the degree of envy that posters think would be triggered in readers (in the poster's version), and how much envy a typical post would trigger in readers themselves (in the reader's version). The comparison between readers' and the posters' reactions is therefore a between-subjects comparison, but the comparison across the five content categories is a within-subjects comparison.

At the end of the questionnaire, Facebook usage behavior, an instructional manipulation check (to check whether participants actually paid attention to instructions), and demographical information were included. Same as the first study, several additional questions had been added for exploratory purposes. Appendix A contains a full list of these questions and additional results.

4.1.2. Measures

Participants in the poster's condition were first asked to report how frequently they tend to post status updates in each post category, with a 5-point ordinal scale from never (1) to very often (5). Expected envy was measured with one item question for each post category: “When you post about [post category], do you think people who read such a post are likely to become a little envious?”, with a continuous slider scale ranging from not at all (0) to very much (6).

Participants in the reader's condition were asked to report the extent to which they like to see status updates from other people in each post category, with a continuous slider scale from not at all (0) to very much (6). Envy was measured with one item question: “When someone posts about [post category], does such a post make you a little envious?”, with a continuous slider scale ranging from not at all (0) to very much (6).

Frequency of visiting Facebook, reading one's news feed, and writing status updates were measured with an ordinal 7-point scale (1 = less than once a month, 2 = one to three times a month, 3 = once a week, 4 = several times a week, 5 = once a day, 6 = several times a day, 7 = all the time). The average time spent on Facebook daily in the past week was measured with an ordinal scale (1 = 10 min or less, 2 = 10–30 min, 3 = 31–60 min, 4 = 1–2 h, 5 = 2–3 h, 6 = more than 3 h). The number of Facebook friends was also measured. In order to check if participants were attentive, a modified version of an instructional manipulation check was included (Oppenheimer, Meyvis, & Davidenko, 2009): Participants were explicitly asked to choose a certain option as indicated in the long instruction. Those who did not read the instruction carefully were likely to click on other options, therefore can be treated as inattentive. Basic demographic information such as gender and age were collected at the end of the questionnaire.

4.1.3. Sample

Four hundred and five American mTurk workers completed the questionnaire. Before analyzing the data, 20 cases were dropped using the following criteria: participants who 1) did not agree with the consent form, 2) failed the instructional manipulation check, and 3) visited Facebook less than once a week. The final sample consisted of 385 participants. The mean age of the current sample was 33.78 years (SD = 9.31), with 49% female participants. In this sample, most participants visited Facebook one to several times a day, read their news feed one to several times a day, posted status updates one to several times a week, and spent about 1 h on Facebook daily in the past week. The average amount of Facebook Friends was 282, SD = 337, median = 185.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Frequency of posting (poster) and willingness to see (reader)

Descriptive results are summarized in Table 4. About 94% of participants in the poster condition had posted a status update about experiential purchases (that is the % of participants that did not answer “never”), 81% had posted about material purchases, 95% had posted about a relationship, 92% had posted about achievements, and 71% had posted about appearances before. Across the five topic categories, there was a clear difference in the frequency of posting (see Table 4), F(4,935) = 39.03, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.14. Posts about “relationship and family” were shared the most frequently, whereas posts about “appearance” were shared the least frequently on Facebook. Of main interest for our study is that participants indicated that they shared their experiential purchases (M = 3.00, SD = 0.93) more frequently than material purchases (M = 2.30, SD = 0.93), t(187) = 8.81, p < .001, d = 0.64, supporting H1.

Table 4.

Descriptive results for frequency of posting, willingness to see, and degrees of envy in Study 3.

|

Post categories |

Poster version (n = 188) |

Reader version (n = 197) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | (SD) | Variables | Mean | (SD) | |

| Experiential purchases | Frequency of posting (1–5) | 3.00d | (0.93) | Willingness to see posts (0–6) | 3.85b | (1.73) |

| Material purchases | 2.30b | (0.93) | 2.35a | (1.74) | ||

| Relationship/family | 3.20e | (1.07) | 4.13c | (1.52) | ||

| Achievements | 2.81c | (1.01) | 3.90b | (1.48) | ||

| Appearance | 2.15a | (1.00) | 2.50a | (1.87) | ||

| Experiential purchases | Expected envy in readers (0–6) | 2.72c | (1.53) | Self-reported envy (0–6) | 2.80c | (1.75) |

| Material purchases | 3.06d | (1.65) | 2.36b | (1.75) | ||

| Relationship/family | 1.94a | (1.64) | 1.50a | (1.50) | ||

| Achievements | 3.03d | (1.68) | 2.25b | (1.69) | ||

| Appearance | 2.35b | (1.74) | 1.39a | (1.64) | ||

Note. Superscripts with different letters indicate a significant difference at p < .05 tested with paired-t tests for each variable.

The extent to which readers liked to read posts also differed across the categories, F(4,980) = 50.54, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.17. It followed a similar pattern as the frequency at which posters indicated to post in each category: Participants indicated to like to read others’ status updates about relationships and experiential purchases the most, and least liked to see selfies (appearance posts) and posts about material purchases. Of notable interest for our current work is that people like to see posts about experiential purchases (M = 3.85, SD = 1.73) more than posts about material purchases (M = 2.35, SD = 1.74), t (196) = 10.25, p < .001, dz = 0.73.

4.2.2. Expected and reported degree of envy

Descriptive results are summarized in Table 4. Readers responses show that some post categories triggered more envy than others, F(4,980) = 25.17, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.09. Of the five categories, a post about experiential purchases was found to elicit the most envy, and posts about both “appearance” and “relationship and family” triggered the least envy. We replicated our earlier findings that readers reported a higher degree of envy when reading a typical post about an experiential purchase (M = 2.80, SD = 1.75) compared with reading about a typical post about a material purchase (M = 2.36, SD = 1.75), t(196) = 4.24, p < .001, dz = 0.30, supporting H2b, but not H3b.

Posters did expect that posts in the different categories would elicit different amounts of envy in readers, F(4,935) = 15.85, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.06. We found that participants, who took the perspective of someone who posts a message, expected that others would be most envious by a typical post about a material purchase or an achievement. Especially important to our research question is that posters thought a typical post about a material purchase would trigger more envy (M = 3.06, SD = 1.64) than a typical post about an experiential purchase would (M = 2.72, SD = 1.53), t(187) = −3.81, p < .001, dz = 0.28. The difference remained significant when we excluded those posters who indicated to have no previous posting experience with these specific content categories, p < .001.

In sum, posters thought that posts about material goods would elicit more envy than posts about experiences would, while readers indicate experiencing the exact opposite. A closer look suggests that posters are quite accurate in how much envy they expected that a typical post about an experiential purchase would elicit, as this did not differ significantly from the reported envy by readers, t(383) = 0.48, p = .628, dz = 0.05. However, for material purchases, the posters overestimated the degree of envy that is experienced by readers: They expected that a typical post about a material purchase would elicit more envy than readers actually indicated to experience, t(383) = 4.07, p < .001, dz = 0.42.

5. General discussion

Across three studies with different methods we found that experiential purchases that were shared on Facebook tend to trigger more intense envy than material purchases. Studies 1 and 2 found that this effect exists because experiential purchases were more important and self-relevant to people compared with material purchases, which increased the intensity of envy.

Furthermore, Study 1 and Study 3 confirmed earlier research (Krasnova et al., 2015; Kumar & Gilovich, 2015) that experiential purchases are shared more frequently than material purchases. This raised the interesting question whether people are aware that such posts about experiential purchases are also likely to trigger envy in others: People do not like others to be envious of them, so why do they post about experiential purchases so often?

One reason why people probably post about experiential purchases more often is revealed in Study 2: Participants indicated to like someone who posts about an experiential purchase more, than someone who posts about a material purchase. This fits with prior work that shows that sharing of experiences improves social bonds (e.g., Kumar & Gilovich, 2015, 2016). A second reason is that people do not seem to realize that experiential purchases are likely to elicit more envy in others, as revealed in Study 3.

5.1. Theoretical implications

A long line of research has documented the positive aspects of experiential purchases: Compared with material purchases, experiential purchases create greater satisfaction, people regret experiential purchases less, and in general they create greater hedonic value (Gilovich et al., 2015). However, no research has investigated the other side, i.e., how posting experiential and material purchases on SNSs is perceived by others and to what extent it causes envy. The current work suggests that sharing experiences might not be uniformly positive. Given that others’ vacation pictures and material possessions are so prevalent on SNSs and experiencing envy on SNSs negatively affects well-being (Verduyn et al., 2017), the current research is very important.

The current research also helps to clarify earlier conflicting findings. Some research found that material purchases triggered more envy (jealousy) because they are more comparable (Carter & Gilovich, 2010), while others found that experiences triggered more envy (Lin & Utz, 2015). It is probably because experiential purchases are more self-relevant and important to people than material purchases (Carter & Gilovich, 2012). Past research found that the more important someone else's accomplishment is to one's own identity, the more likely it is to trigger envy (Salovey & Rodin, 1991). Study 1 and Study 2 indeed replicated that experiential purchases were more self-relevant to most Facebook users, and showed that the difference in self-relevance partially explained the extra envy that experiential purchases tend to elicit. However, we did not find support for the competing idea that material purchases are easier to compare than experiential purchases are.

Another implication of the current research is the slightly more nuanced view of the effect that experiential purchases have in enhancing social relations. On the one hand, due to a higher story value of experiential purchases than material purchases (Bastos & Brucks, 2017; Kumar & Gilovich, 2015), people are more likely to share their experiential purchases than material purchases online, as supported by the results of Study 1 and 3. Readers also liked the poster more when sharing experiential purchases than when sharing material purchases (as indicated by Study 2), and readers are more willing to read about other's experiential purchases than about material purchases (Study 3). Despite these many positive effects that have been identified in previous research (and we verify here), experiential purchases are also likely to elicit stronger negative feelings (envy in this case). This research provided a more comprehensive view on how sharing experiential and material purchases changes attitudes and emotions. Even though reading other's experiential purchases was found to trigger more envy than material purchases, it is also confirmed that sharing experiential purchases is better for social bonding than sharing material purchases is.

Also note that quite some research exists that shows that envy can be detrimental for social relationships and can lead to outright negative behavior towards the envied person (Duffy & Shaw, 2000; Oswald & Zizzo, 2001; Parks, Rumble, & Posey, 2002). The negative emotion of envy can be resolved by either trying to pull down the other from their superior position (a motivation often associated with malicious envy) in a negative way, or by motivating oneself to improve (a motivation often associated with benign envy) in a positive way (Van de Ven, Zeelenberg, & Pieters, 2009). However, only malicious envy leads to negative behavior towards the envied, and benign envy does not (Van de Ven et al., 2009). Existing research (see Van de Ven, 2016 for an overview) can provide valuable insights into how one can gain the most benefit from sharing about experiential purchases without triggering the malicious form of envy. For example, the resulting envy is more likely to be of the benign form when one deserves the envied object more (Van de Ven, Zeelenberg, & Pieters, 2012), or by focusing attention on aspects of the desired purchase (and less on oneself enjoying it; Crusius & Lange, 2014).

Previous research on materialism has suggested a strong link between envy and materialism. For example, Belk (1984) measure of trait materialism that measures how materialistic a person is, has an envy subscale. This subscale measures how envious someone is of material objects owned by others. We agree that individuals who tend to be envious of material objects are more materialistic persons. But the reason is not an inherent relation between envy and materialism, but rather that people are more envious for things that are more important to them; for a materialistic person, material objects are important and thus likely to elicit relatively more envy. Similarly, other research found that people who are more extraverted and more open to experience tend to prefer more experiential purchases (Howell, Pchelin, & Iyer, 2012), because experiences (for openness) and doing things with other people (for extraverts) are more important to them. For people who score high on these traits we therefore predict even stronger envy towards experiential purchases (relative to material ones). Envy is thus a useful signal to see what people find important, but we caution against an interpretation that envy and materialism are inherently linked.

Finally, our study has the interesting finding that people mispredict what other people are likely to be envious of. Where people themselves are more envious towards experiential purchases of others, they think others will be more envious of material purchases. A consequence of this is that people often do not realize others are likely to be envious of them when they share their experiences. Theoretically, it is also interesting why this misprediction occurs: Do we overestimate how important other people find material goods? Or is there another cause?

5.2. Practical implications

Besides the theoretical implication as mentioned above, the current work also has practical implications for social media marketers, SNS platform providers, and users. As discussed before, the malicious consequences of envy might harm the relationship with the envied person, as it is likely to leads to more destructive tendencies (Oswald & Zizzo, 2001; Van de Ven et al., 2009); but if the envy is of the benign type, it can potentially motivate people to “keep up with the Joneses” and improve their own position (Van de Ven et al., 2009). Some work has been conducted on the role of envy in increasing the willingness to pay for envied products (Crusius & Mussweiler, 2012; Van de Ven et al., 2011a). As the posts about experiential purchases trigger the most envy on SNSs, marketers can also utilize the emotion of envy for better targeted advertising that fits with the motivation that is likely active at that moment (e.g., by showing the tourism-related ads to those who are envious about friends’ vacation experiences). This research is also useful for those “influencers” those who make a living with their social media presence. Merely concerning the mechanism of envy, the effect of promoting might be better (and even be more effective) when it is about experiences (e.g., a post about a city trip) than products (e.g., a post about a bag).

As a higher degree of envy increases user's switch intention (Lim & Yang, 2015), it is also important for SNS providers to know when and why envy is triggered. Though SNS providers are trying to provide users with news that is more relevant, the current research highlighted that such content is also more likely to trigger envy. More systematic research is needed to help SNS providers to further improve its news feed display algorithm.

For SNS users who post frequently, it is interesting to know which type of posts on SNSs are being liked more by others. The results in the third study showed that readers are willing to see posts about other's relationship and family, but not too much about other's material purchases and selfies. With regard to the emotion of envy, it is also important to make posters aware of the prediction error: It is actually experiential purchases that are likely to trigger the most envy. However, it does not necessarily mean that users should not post about their experiential purchases. There is an interesting discrepancy here: Though posts about experiential purchases trigger envy more intensively and more frequently, they were still found to be good for social relationships and well-being, and readers were willing to see such posts. The current research provides guidance to users about what to share on SNSs.

5.3. Limitations and future research

There are some limitations of the current research. First, even though multiple studies were utilized to examine whether experiential or material purchases elicit more envy, it is difficult to exclude all confounding factors. For example, in Study 2 we manipulated a purchase about music to be experiential (concert visit) or material (music player), but the conditions also for example differ in that a concert visit is also a social experience. Although the range of different studies we used helps to balance out potential confounds, it does point to the fact that experiences and material purchases often differ on a number of dimensions. Future research can help identify whether there are more characteristics, in addition to the differences we found for self-relevance, that can affect envy.

Another point is that because of the negative stereotype associated with being materialistic (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003), readers in the current studies might be reluctant to admit that they feel envious towards material goods; therefore, it is possible that readers might feel more envious after reading a post about material purchases but they did not report it in the questionnaire. However, please note that the mean scores on the envy-subscale of Belk (1984) materialism scale are not very low, indicating that people do not seem to mind admitting being (somewhat) envious of material goods.

A third point is that the one-item measures for comparability and self-relevance may not be reliable. Even though the concepts of self-relevance and comparative nature were often mentioned in the literature (Carter & Gilovich, 2010; Smith, 2004), no good measures of those concepts are available in the relevant research. As a result, measurements were created based on the authors’ preliminary understanding of the concepts.

Fourth, even though this research claims that the results are valid on SNSs, it mainly used the platform of Facebook and used samples from developed countries. Future research is encouraged to examine if experiential purchases also trigger more envy than material purchases using different samples and social networking platforms.

There are several potential directions for future research. As a first step, this paper only examined the general emotion of envy. Future research could also examine possible differences in the type of envy elicited by experiential or material purchases. An important distinction in envy research is that between benign and malicious envy (Van de Ven et al., 2009). Although initial research on the antecedents of these envy types (Van de Ven et al., 2012) would not predict any differences in whether experiential or material purchases are more likely to trigger benign/malicious envy, the current research suggests that those who shared their experiential purchases are liked more than those who shared material purchases. If the sharing of experiences increases liking, it might become more likely that the resulting envy could be of the benign type.

It is important to understand under which conditions envy is triggered on SNSs. So far, a systematic research on this topic is not available yet. The current work only focused the post content (mainly experiential vs. material category). However, the emotion of envy on SNSs is not only influenced by the content of the post, but also depends on the personality trait of the reader and the relationship with the poster. For example, Appel et al. (2015) found that depressed social network users were likely to experience a higher degree of envy than non-depressed users. Lin and Utz (2015) found that the relationship closeness with the poster predicted the degree of benign envy. Furthermore, personality traits such as materialism (Belk, 1984; Richins, 2004) and relationship characteristics like the perceived similarity (Tesser, 1991) could also be potential moderators of the current research. Future research could further explore the potential moderators and the interactions between the content of the post, the relationship with the reader, and the personality trait of the poster.

6. Conclusion

The current research contributes to explaining when and why people feel envious when browsing SNSs. Social network users thought that their posts about material purchases would elicit more envy in others, but it was actually the posts about experiential purchases that elicited more envy. This is due to the experiential purchases being seen as more self-relevant and important to one's identity. Also, posts about experiential purchases are more frequent than posts about material purchases, making these not only elicit a higher degree of envy but also elicit envy more frequently. This research not only contributes to the literature on experiential vs. material purchases and the emotion of envy, but also provides practical implications for SNS marketers, users, and platform providers.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ ERC grant agreement no 312420.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.049.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Appel H., Crusius J., Gerlach A.L. Social comparison, envy, and depression on facebook: A study looking at the effects of high comparison standards on depressed individuals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2015;34(4):277–289. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2015.34.4.277 [Google Scholar]

- Bastos W., Brucks M. How and why conversational value leads to happiness for experiential and material purchases. Journal of Consumer Research. 2017;44(3):598–612. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx054 [Google Scholar]

- Belk R. Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness. Advances in Consumer Research. 1984;11:291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Caprariello P.A., Reis H.T. To do, to have, or to share? Valuing experiences over material possessions depends on the involvement of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104(2):199–215. doi: 10.1037/a0030953. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter T.J., Gilovich T. The relative relativity of material and experiential purchases. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(1):146–159. doi: 10.1037/a0017145. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter T.J., Gilovich T. I am what I do, not what I have: The differential centrality of experiential and material purchases to the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(6):1304–1317. doi: 10.1037/a0027407. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crusius J., Lange J. What catches the envious eye? Attentional biases within malicious and benign envy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2014;55:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.05.007 [Google Scholar]

- Crusius J., Mussweiler T. When people want what others have: The impulsive side of envious desire. Emotion. 2012;12(1):142–153. doi: 10.1037/a0023523. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSteno D.A., Salovey P. Jealousy and the characteristics of one's rival: A self-evaluation maintenance perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22(9):920–932. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296229006 [Google Scholar]

- Duffy M.K., Shaw J.D. The salieri syndrome: Consequences of envy in groups. Small Group Research. 2000;31(1):3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649640003100101 [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202 [Google Scholar]

- Foster G.M., Apthorpe R.J., Bernard H.R., Bock B., Brogger J., Brown J.K. The anatomy of envy: A study in symbolic behavior. Current Anthropology. 1972;13(2):165–202. https://doi.org/10.2307/2740970 [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich T., Kumar A., Jampol L. A wonderful life: Experiential consumption and the pursuit of happiness. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2015;25(1):152–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2014.08.004 [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. Vols. 3–4. Guilford; New York, NY: 2013. https://doi.org/978-1-60918-230-4 (Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis). [Google Scholar]

- Howell R.T., Pchelin P., Iyer R. The preference for experiences over possessions: Measurement and construct validation of the Experiential Buying Tendency Scale. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2012;7(1):57–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.626791 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Hoegg J., Dahl D.W. Consumer reaction to unearned preferential treatment. Journal of Consumer Research. 2013;40(3):412–427. https://doi.org/10.1086/670765 [Google Scholar]

- Judd C.M., Kenny D.A., McClelland G.H. Estimating and testing mediation and moderation in within-subject designs. Psychological Methods. 2001;6(2):115–134. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.2.115. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.6.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova H., Wenninger H., Widjaja T., Buxmann P. 11th international conference on wirtschaftsinformatik. 2013. Envy on facebook: A hidden threat to users' life satisfaction? pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova H., Widjaja T., Buxmann P., Wenninger H., Benbasat I. Why following friends can hurt you: An exploratory investigation of the effects of envy on Social Networking Sites among college-age users. Information Systems Research. 2015;26(3):585–605. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2015.0588 [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Gilovich T. Some “thing” to talk about? Differential story utility from experiential and material purchases. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2015;41(10) doi: 10.1177/0146167215594591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215594591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Gilovich T. To do or to have, now or later? The preferred consumption profiles of material and experiential purchases. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2016;26(2):169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.06.013 [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Mann T.C., Gilovich T. The aptly buried “I” in experience: Experiential purchases foster social connection. Manuscript in preparation. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lim M., Yang Y. Effects of users' envy and shame on social comparison that occurs on social network services. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;51:300–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.013 [Google Scholar]

- Lin R., Utz S. The emotional responses of browsing Facebook: Happiness, envy, and the role of tie strength. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;52:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer D.M., Meyvis T., Davidenko N. Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(4):867–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.009 [Google Scholar]

- Oswald A.J., Zizzo D.J. Are people willing to pay to reduce others' incomes? Annales d’Économie et de Statistique. 2001;63/64:39–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462300006280 [Google Scholar]

- Parks C.D., Rumble A.C., Posey D.C. The effects of envy on reciprocation in a social dilemma. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28(4):509–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202287008 [Google Scholar]

- Parrott W.G., Smith R.H. Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64(6):906–920. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.906. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richins M.L. The material values scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research. 2004;31(1):209–219. https://doi.org/10.1086/383436 [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Mosquera P.M., Parrott W.G., Hurtado de Mendoza A. I fear your envy, I rejoice in your coveting: On the ambivalent experience of being envied by others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(5):842–854. doi: 10.1037/a0020965. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani S., Grappi S., Bagozzi R.P. The bittersweet experience of being envied in a consumption context. European Journal of Marketing. 2016;50(7/8) https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230910978511 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig E., Gilovich T. Buyer's remorse or missed opportunity? Differential regrets for material and experiential purchases. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(2):215–223. doi: 10.1037/a0024999. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P., Rodin J. Some antecedents and consequences of social-comparison jealousy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47(4):780–792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.4.780 [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P., Rodin J. Provoking jealousy and envy: Domain relevance and self-esteem threat. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1991;10(4):395–413. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1991.10.4.395 [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.H. Envy and its transmutations. In: Tiedens L.Z., Leach C.W., editors. The social life of emotions. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 2004. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.H., Kim S.H. Comprehending envy. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:46–64. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.46. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steers M.-L.N., Wickham R.E., Acitelli L.K. Seeing everyone else's highlight reels: How Facebook usage is linked to depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2014;33:701–731. [Google Scholar]

- Tandoc E.C., Ferrucci P., Duffy M. Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;43:139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.053 [Google Scholar]

- Tesser A. Emotion in social comparison and reflection processes. Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research. 1991:115–145. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boven L., Campbell M.C., Gilovich T. Stigmatizing materialism: On stereotypes and impressions of materialistic and experiential pursuits. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36(4):551–563. doi: 10.1177/0146167210362790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210362790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boven L., Gilovich T. To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(6):1193–1202. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven N. Envy and its consequences: Why it is useful to distinguish between benign and malicious envy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2016;10(6):337–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12253 [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven N. Envy and admiration: Emotion and motivation following upward social comparison. Cognition & Emotion. 2017;31(1):193–200. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2015.1087972. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1087972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven N., Zeelenberg M., Pieters R. Leveling up and down: The experiences of benign and malicious envy. Emotion. 2009;9(3):419–429. doi: 10.1037/a0015669. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015669 (Washington, D.C.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven N., Zeelenberg M., Pieters R. Warding off the evil eye: When the fear of being envied increases prosocial behavior. Psychological Science: A Journal of the American Psychological Society / APS. 2010;21(11):1671–1677. doi: 10.1177/0956797610385352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610385352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven N., Zeelenberg M., Pieters R. The envy premium in product evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research. 2011;37(6):984–998. https://doi.org/10.1086/657239 [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven N., Zeelenberg M., Pieters R. Why envy outperforms admiration. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37(6):784–795. doi: 10.1177/0146167211400421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211400421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven N., Zeelenberg M., Pieters R. Appraisal patterns of envy and related emotions. Motivation and Emotion. 2012;36(2):195–204. doi: 10.1007/s11031-011-9235-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9235-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduyn P., Ybarra O., Résibois M., Jonides J., Kross E. Do Social Network Sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2017;11(1):274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033 [Google Scholar]

- Wert S.R., Salovey P. A social comparison account of gossip. Review of General Psychology. 2004;8(2):122–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.122 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.