Abstract

We present a case of beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration, a form of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. The patient harbored a novel mutation in the WDR45 gene. A detailed video and description of her clinical condition are provided. Her movement disorder phenomenology was characterized primarily by limb stereotypies and gait dyspraxia. The patient’s disability was advanced by the time iron-chelating therapy with deferiprone was initiated, and no clinical response in terms of cognitive function, behavior, speech, or movements were observed after one year of treatment.

Keywords: Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration, neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation, stereotypies, deferiprone

Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN) is a form of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA; type 5), which was initially described as static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood (SENDA). BPAN is very rare, with fewer than 50 cases reported to date [1]. The disease typically starts in early childhood with intellectual impairment and seizures. The disease progresses during adolescence or early adulthood with the emergence of dementia and movement disorders, especially dystonia and parkinsonism [1,2]. Rett syndrome-like behaviors, including hand stereotypies, may be observed. The vast majority of cases are female and sporadic, resulting from a de novo mutation in the WD repeat-containing protein 45 (WDR45) gene located at Xp11.23 [1,2]. The gene product, WIPI4, is a 7-bladed beta-propeller protein believed to be involved in autophagy, and there is preliminary evidence suggesting that BPAN could be a tauopathy [3].

We report a case of a 29-year-old woman of ethnic Indian descent with typical imaging results and clinical presentation for BPAN (intellectual impairment, epilepsy beginning with febrile seizures, Rett-like features, including loss of language, and the presence of stereotypies and gait dyspraxia) as well as a novel mutation in the WDR45 gene (c.249G>A in exon 6). To the best of our knowledge, this is only the second patient of ethnic Indian descent reported with BPAN [4]. A detailed video and description of her clinical condition are provided. Our experience with deferiprone treatment is also described; we are aware of only one prior case report of a BPAN patient treated with deferiprone.

CASE REPORT

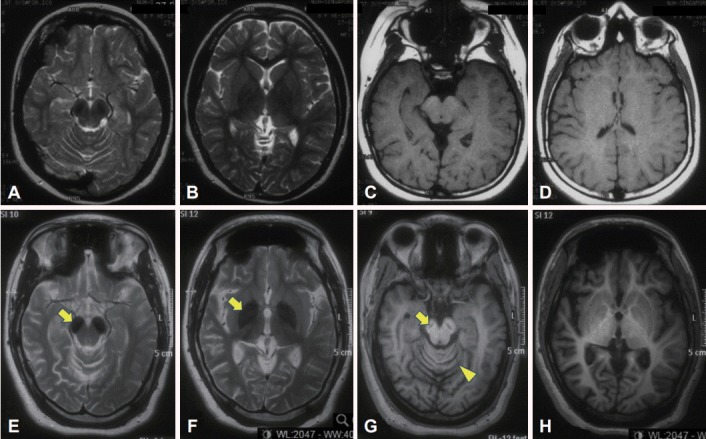

The patient was the second child of a nonconsanguineous couple. Birth and early developmental history were unremarkable. There was no history of neurological disorders in the immediate or extended family. At 13 months of age, she started having seizures associated with fever and urinary tract infections. The seizures became more frequent during her early childhood and were described as episodes of absence, brief jerks, or sudden forward flexion of the trunk. She became hyperactive with poor attention span and was diagnosed with a learning disability. EEG revealed epileptiform discharges, but brain MRI results were reportedly normal (although in retrospect, bilateral T2 hypointensity could be seen in the substantia nigra) (Figure 1, top panel). She was treated with clonazepam and methylphenidate. At the age of eight, sodium valproate and levetiracetam were added, and the seizures were controlled. She attained her best level of function in her teenage years. She was able to walk independently without a walking aid and even run. She could speak in brief sentences but was never able to read or write.

Figure 1.

Brain MRI scans performed at ages eight (top panel) and 24 (bottom panel). The first MRI was initially reported as normal but in retrospect shows bilateral T2 hypointensity in the substantia nigra (A). However, the first MRI shows normal signal in the globus pallidus (B) (more prominent nigral vs. pallidal involvement is typical of beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration) [1]. There is also mild thinning of the posterior corpus callosum, seen on the sagittal T1 image (not shown). Later, marked T2 hypointensity in the substantia nigra and cerebral peduncle (arrow) (E) and globus pallidus (arrow) (F) has developed bilaterally. There is a “slit” of T1 hypointensity in the nigra with a faint rim of hyperintensity, the so-called “halo” sign (arrow) (G), as well as global cerebral atrophy (G and H, compared to C and D) and cerebellar atrophy (arrowhead) (G).

In her early 20s, she started to deteriorate with reduced ability to walk and was falling backwards, followed soon after by cognitive decline. Ophthalmological examination revealed optic atrophy without retinal pigmentary changes. EEG showed thetadelta range slowing of the background rhythm with epileptiform discharges. Brain MRI repeated at age 24 (Figure 1, lower panel) showed marked bilateral T2 hypointensity in the substantia nigra and globus pallidus and a “slit” of T1 hypointensity in the nigra with a faint rim of hyperintensity, as well as global cerebral atrophy and cerebellar atrophy. Brain magnetic resonance spectroscopy was normal. Molecular genetic testing revealed a nucleotide change of guanine (G) to adenine (A) at nucleotide position c.249 (c.249G>A) in exon 6 in one copy of the WDR45 gene (accession number NM 007075.3) (Knight Diagnostic Laboratories, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA). This variant is not annotated in any published database, including Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), 1000 Genomes, or the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project Exome Variant Server (EVS). This mutation predicts an amino acid change of tryptophan (Trp) to a stop codon at codon p.83 (p.Trp83X) (accession number NP 009006) within the WD40 repeat domain of WDR45. Additionally, this mutation is predicted to be pathogenic, potentially resulting in a truncated WDR45 protein, which lacks amino acids 84–361 [5]. Proteomic analysis may be explored in the future to confirm the truncation. Both parents tested negative for the mutation, and screening of an additional 20 control samples from the local population was negative. Her older sister, who lives overseas, also had a negative genetic test result. The patient’s other blood investigations were normal, including blood film (no acanthocytes) and lactate.

Upon treatment with sodium valproate (200 mg bid), levetiracetam (500 mg bid), baclofen (10 mg bid), trihexyphenidyl (1.5 mg daily), and clonazepam (0.5 mg bid), her seizures were controlled, and episodic limb muscle spasms were reduced. Previous trials of levodopa treatment resulted in generalized dyskinesia and had to be stopped. Her condition when age 28–29 is shown in the video and described in the video legend (please see Supplementary Video 1 in the online-only data supplement).

A trial of deferiprone, an iron-chelating agent able to cross the blood-brain barrier, was initiated at a dose of 250 mg bid (body weight 65 kg). When this was uptitrated to 500 mg bid, i.e. approximately 15 mg/kg/day (a moderate 20–30 mg/kg/day dose has been suggested for chelation in neurodegenerative disorders, whereas typically approximately 80 mg/kg/day is used to treat iron overload due to blood transfusion in thalassemia) [6-8], the patient experienced distressing abdominal pain, anorexia, insomnia, restlessness, and agitation, and the treatment had to be withheld. Deferiprone was subsequently resumed and gradually increased to 250 mg bid, but she again suffered the same side effects as before. Thus, the dosage had to be reduced back to 250 mg daily. After treatment with deferiprone for a year, there has been no apparent clinical improvement in terms of cognitive function, behavior, speech, or movements. The patient’s symptomatic treatments remained stable over this period. Repeat brain imaging was not performed, as this would have necessitated administration of general anesthesia.

Interestingly, iron indices prior to initiation of deferiprone showed low systemic iron stores with transferrin saturation of 10% (reference range 20–45%); the serum ferritin level (52.9 μg/L, reference range 10.0–291.0 μg/L), hemoglobin level (121 g/L), and mean corpuscular volume (81 fL) were in the lower range of normal. There was no history of menorrhagia or other overt blood loss, and serum vitamin B12 and folate levels were in the normal range. We were concerned about the possibility of inducing global iron depletion in a patient who was already mildly hypoferremic; however, her transferrin saturation and ferritin levels (ranged between 19–20% and 53.7–67 μg/L, respectively) did not drop further during deferiprone treatment .

DISCUSSION

We report a case of BPAN with a novel mutation in the WDR45 gene with illustrative video and detailed description of the movement disorder phenomenology, characterized primarily by limb stereotypies and gait dyspraxia. Sequential brain imaging showed evolution of iron deposition and atrophy over time, with involvement of the substantia nigra occurring earlier and more prominently than in the pallidum, as previously described [1].

Chelation therapy with deferiprone to remove excessive iron in the brain has shown some promise in pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), the most common form of NBIA. In one study (n = 9), treatment for 6 months resulted in improvement of radiological but not clinical status; the authors noted that the majority of their patients were already in an advanced stage (e.g., wheelchairbound) by the time of treatment initiation [7]. Another cohort of patients (n = 6) with milder disability overall compared to the aforementioned study completed 3–4 years of treatment. This cohort showed radiological improvement and stabilization of motor symptoms [8]. However, convincing evidence of clinical benefit is lacking. No serious adverse events were reported [7,8]. Unfortunately, although perhaps not unexpectedly since she was already severely disabled by the time of deferiprone initiation, our patient did not show any clinical response to treatment after one year. Furthermore, only a low dose of deferiprone could be used due to poor patient tolerance. We are aware of only one other published case report of a patient with BPAN (with much milder motoric impairment compared to our patient) who was treated with deferiprone at a relatively high dose of 1,000 mg bid for four months. The treatment coincided with worsening of the patient’s parkinsonian features and was ceased for this reason [9].

This case adds to the existing literature on a very rare neurodegenerative disease. It is hoped that greater awareness of the NBIAs, including rare forms such as BPAN, will lead to future advances in the scientific understanding and management of these disabling diseases [10].

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patient’s family for their consent and participation in this report, including publication of the video. SAS was supported by the Else Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://dx.doi.org/10.14802/jmd.17082.

Video 1.

The patient has an “open mouth” facies with a vacuous smile and inappropriate laughter. Speech is limited to highpitched sounds and simple single words (e.g., saying “cry” when she is apparently happy), and comprehension is severely impaired (e.g., unable to follow verbal or gestural commands to perform repetitive movements when testing for limb bradykinesia). Spontaneous eye movements are normal. Midline stereotypies in the hands (e.g., fiddling with an object and hand tapping) are seen. There is abnormal posturing (e.g., intermittently crossing the left leg, sometimes even while she is walking, or holding the arms raised above her head). Although, these look volitional rather than dystonic (likely also representing stereotypies). In the third video segment, intermittent choreiform movements occur in the right leg, which again probably represent stereotypies. A strong grasp response is present bilaterally (e.g., patient reaching out for the examiner’s hand); pollicomental and palmomental reflexes are also present bilaterally (not shown). The patient is only able to stand and walk with 2-person assistance (requiring support from the back to prevent backward falls) in an unusual high-stepping or marching fashion—probably best classified as a gait dyspraxia. Moderate cogwheel rigidity is present at the wrists, as well as mild rigidity in the left leg. However, spontaneous movements do not appear bradykinetic, and there is no resting or postural tremor. There are no pyramidal signs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gregory A, Kurian MA, Haack T, Hayflick SJ, Hogarth P. Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration. [cited 2017 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424403/?report=printable. [PubMed]

- 2.Nishioka K, Li G, Yoshino H, Li Y, Matsushima T, Takeuchi C, et al. High frequency of beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN) among patients with intellectual disability and young-onset parkinsonism. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.01.020. e9-2004.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paudel R, Li A, Wiethoff S, Bandopadhyay R, Bhatia K, de Silva R, et al. Neuropathology of beta-propeller protein associated neurodegeneration (BPAN): a new tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:39. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0221-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoganathan S, Arunachal G, Sudhakar SV, Rajaraman V, Thomas M, Danda S. Beta propellar protein-associated neurodegeneration: a rare cause of infantile autistic regression and intracranial calcification. Neuropediatrics. 2016;47:123–127. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1571189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haack TB, Hogarth P, Kruer MC, Gregory A, Wieland T, Schwarzmayr T, et al. Exome sequencing reveals de novo WDR45 mutations causing a phenotypically distinct, X-linked dominant form of NBIA. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:1144–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boddaert N, Le Quan Sang KH, Rötig A, Leroy-Willig A, Gallet S, Brunelle F, et al. Selective iron chelation in Friedreich ataxia: biologic and clinical implications. Blood. 2007;110:401–408. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-065433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zorzi G, Zibordi F, Chiapparini L, Bertini E, Russo L, Piga A, et al. Iron-related MRI images in patients with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) treated with deferiprone: results of a phase II pilot trial. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1756–1759. doi: 10.1002/mds.23751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cossu G, Abbruzzese G, Matta G, Murgia D, Melis M, Ricchi V, et al. Efficacy and safety of deferiprone for the treatment of pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA): results from a four years follow-up. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:651–654. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonderico M, Laudisi M, Andreasi NG, Bigoni S, Lamperti C, Panteghini C, et al. Patient affected by beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration: a therapeutic attempt with iron chelation therapy. Front Neurol. 2017;8:385. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jinnah HA, Albanese A, Bhatia KP, Cardoso F, Da Prat G, de Koning TJ, et al. Treatable inherited rare movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2018;33:21–35. doi: 10.1002/mds.27140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1.

The patient has an “open mouth” facies with a vacuous smile and inappropriate laughter. Speech is limited to highpitched sounds and simple single words (e.g., saying “cry” when she is apparently happy), and comprehension is severely impaired (e.g., unable to follow verbal or gestural commands to perform repetitive movements when testing for limb bradykinesia). Spontaneous eye movements are normal. Midline stereotypies in the hands (e.g., fiddling with an object and hand tapping) are seen. There is abnormal posturing (e.g., intermittently crossing the left leg, sometimes even while she is walking, or holding the arms raised above her head). Although, these look volitional rather than dystonic (likely also representing stereotypies). In the third video segment, intermittent choreiform movements occur in the right leg, which again probably represent stereotypies. A strong grasp response is present bilaterally (e.g., patient reaching out for the examiner’s hand); pollicomental and palmomental reflexes are also present bilaterally (not shown). The patient is only able to stand and walk with 2-person assistance (requiring support from the back to prevent backward falls) in an unusual high-stepping or marching fashion—probably best classified as a gait dyspraxia. Moderate cogwheel rigidity is present at the wrists, as well as mild rigidity in the left leg. However, spontaneous movements do not appear bradykinetic, and there is no resting or postural tremor. There are no pyramidal signs.