ABSTRACT

Background: The provision of respectful and satisfactory maternity care is essential for promoting timely care-seeking behaviour, and ultimately ensuring the health and well-being of mothers and their babies. Disrespectful and abusive care has been recognized as one of the barriers to seeking timely maternity health services. However, the issue has not been adequately researched in community settings in low- and middle-income countries using validated measurement tools.

Objective: This study was conducted to assess the extent of, and factors associated with, disrespectful and abusive maternity care reported by women who utilized facility-based delivery services in northern Ethiopia.

Methods: We conducted a community-based cross-sectional study in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Women who gave birth in the preceding year and visited health institutions for these deliveries were selected using a multistage cluster sampling procedure. Data were collected using a pretested questionnaire. Six domains of disrespect and abuse (D and A) were included in the questionnaire. Socio-demographic and obstetric related factors associated with D and A were tested using a negative binomial regression model.

Results: Of the 1125 women in the sample, 248 (22%; 95% CI: 19.8%, 24.4%) reported at least one incident of D and A during delivery at a public health facility in northern Ethiopia. Higher incidents of D and A were reported by women who were older than 19 years at the time of delivery (aIRR = 2.649 (95% CI: 1.455, 4.825) compared to younger women. Incidents of D and A were reported more by women residing in urban areas, by women educated to the ninth grade and above, by women who experienced longer labour duration, and also by women who were not permitted to have support persons attend labour and delivery.

Conclusions: A fifth of the women reported D and A while receiving care during labour and delivery. Policies and practices aimed at ensuring universal coverage for institutional deliveries need to promote respectful maternity care for women in all facilities.

SPECIAL ISSUE: Gender and Health Inequality

KEYWORDS: Antenatal care, companionship, labour and delivery, respectful care, Tigray

Background

The provision of respectful maternity services is a key strategy for preventing maternal suffering and deaths in sub-Saharan Africa [1,2]. Strategies such as locating birthing facilities close to communities and improving transportation are not sufficient inducements to encourage pregnant women to deliver in health facilities [3]. Individual and group perceptions and experiences in relation to the quality of care can influence the utilization of maternity services [4,5]. Improving the quality of maternity services and the manner in which they are delivered is critical for increasing service utilization [6,7].

The concept of ‘respectful maternity care’ is very difficult to measure because it is mainly dependent on women’s perceptions. As a result, this topic has been either ignored or under-reported [8]. Disrespectful and abusive care includes impoliteness of care providers, inappropriate reprimands, shouting at the client, lack of empathy, refusal to assist, threatening clients for their non-compliance, and denying clients opportunities to choose or give an opinion on the care they are receiving [9–11]. In recent years, the issue has received greater attention due to improved methods to operationally define and measure the phenomena [12–14]. However, community-based information on disrespectful and abusive care in sub-Saharan Africa is still lacking. Most previous studies were conducted in health institutions, where social desirability bias and fear of retaliatory action can potentially underestimate the extent of the problem. We assessed the quality of maternity care from users’ perspectives in order to bring women’s voices into the maternal health quality improvement agenda. This community-based study was conducted to assess the extent of, and factors associated with, disrespectful and abusive maternity care reported by women who utilized facility-based delivery services in northern Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting

Tigray regional state in Ethiopia has 52 districts/woredas (34 rural and 18 urban) and 792 kebeles which are the lowest administrative units (722 rural and 70 urban kebeles) [15]. Within the region, there are 668 health posts, 218 health centres and 28 hospitals (11 primary, 16 general and 1 specialized). The general health service coverage is estimated to be 96%. In 2014, the regional health bureau report indicated 100% coverage for antenatal care, 55.3% for deliveries attended by skilled attendants, and 69.6% for postnatal care [15]. Maternity services in Ethiopia are provided free of charge in all government-owned health facilities. In this study area in northern Ethiopia, private health facilities rarely provide delivery services. Incidents reported here refer only to delivery facilities in government-run health facilities.

Study participants

The study utilized a community based cross-sectional design. Women who gave birth in the preceding 12 months and visited public health facilities for birthing were the study subjects. This study period was chosen in order to achieve an adequate sample size and minimize recall bias. Women were selected for the study using a multistage sampling procedure. In the first stage, six districts were selected by simple random sampling. In the second stage, nine kebeles (three from urban and six from rural districts) were selected at random proportionate to the population size. The calculated sample size was proportionally allocated (736 to rural and 390 to urban kebeles). Rural kebeles with poor or no access to health services were excluded from the study sample. In the third stage, after selecting a random starting point, households with eligible women were sequentially enrolled until the allocated sample size for each selected kebele was achieved.

Data collection tool and data collection

Data were collected, using an interviewer-administered questionnaire, over the period August to September 2015. The questionnaire was designed to collect information on socio-demographic characteristics, obstetric related conditions, and women’s experiences and perceptions of health services during labour and delivery. Based on Bowser and Hill’s report, this study measured six domains of disrespectful and abusive care which include: physical abuse, non-consensual care, non-confidential care, non-dignified care, discrimination based on specific patient attributes, and abandonment of care [8]. A seventh domain which captures information on detention was not included. Detainment in a health facility can occur because of failure to pay healthcare fees, and this study includes only maternity services provided without payment in government health facilities. The study instrument was first validated for content by experts, and then pretested on 50 women residing in similar settings outside the study area to check for ease of understanding and the time needed to complete the interview. The instrument was translated from English to the local language, Tigrigna, and then back-translated to English to ensure consistency in meaning.

Health extension workers, who are formal community-level primary healthcare providers, implemented the questionnaire in each village. This facilitated a high response rate because they were able to establish rapport with the mothers. Once a household with eligible women was identified there were up to three repeat visits to enroll the women in the study.

During data collection, the completeness of the questionnaires was checked on a daily basis by the field supervisors and the principal investigator. Data were entered using Epidata version 3.1 statistical software and then transferred to SPSS version 20 for analysis.

Covariates

Information on residence, occupation, household head and permission for support persons to attend labour and delivery was captured and used to derive categorical variables. Maternal age was categorized into 3, as less than 20 years, 20–34, and 35 and above. Maternal educational status was categorized into 4, as illiterate, primary (1–4 grade), junior secondary (5–8 grade) and secondary and above. Total number of births to the mother were categorized into 3, as less than 3 births, 3–5 births, and 5 or more. Maternal age at marriage was categorized into 2, as 20 or less years, and more than 20 years. Duration of labour at the facility was categorized into 3, as less than 1 hour, 1–12 hours, 13–23 hours, and 24 or more hours.

The outcome of interest was count of occurrences of disrespectful and abusive practices/events, taking into account responses to all items in the questionnaire. An indicator variable was derived whereby respondents were classified as having experienced D and A if they reported at least one incident; women who scored zero were classified as not having experienced D and A.

Analysis

Given that the outcome was a count, the appropriate model would have been a Poisson regression. However, the assumptions for this model were violated in terms of dispersion; the mean was 0.54, and the variance was 1.73 indicating the presence of over-dispersion. Negative Binomial Regression was chosen as the preferred model. The measure of association for the Negative Binomial Model is presented as the Incidence Rate Ratio and 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was set at alpha 0.05. Variables were included in the multivariable Negative Binomial Model if their p-value was < 0.25 in bivariate analysis.

Data were missing at random for the economic variable, which referred to household income. However, this variable was not included in the analysis because the amount of missing data was > 10%. Missing data for all other variables was < 10%.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from Mekelle University Institutional Review Board (IRB). A written informed consent was obtained from each study participant; participants unable to sign were asked to give a thumbprint. Interviews were conducted in privacy and completed questionnaires were kept confidential and stored in a safe place.

Results

Consistent with the sample size calculation, 1125 women were invited to participate in this study. All those invited agreed to participate. The majority of the women (902, 80.2%) were in the 20–34 years age category. The mean and median age of the women were 26.8 and 26.0 years, respectively. The majority of women were housewives (827, 73.5%) and rural residents (738, 65.6%). About one-third (415, 36.9%) of the women were illiterate (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study subjects, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2015.

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | less than 20 years | 76 | 6.7 |

| 20–34 years | 902 | 80.2 | |

| 35 years and above | 147 | 13.1 | |

| Ethnicity | Tigray | 1115 | 99.1 |

| Erop | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Amhara | 6 | 0.5 | |

| Afar | 3 | 0.3 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 995 | 88.4 |

| Muslim | 125 | 11.1 | |

| Catholic | 4 | 0.4 | |

| Protestant | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Marital status | Married | 1069 | 95 |

| Unmarried | 17 | 1.5 | |

| Divorced | 35 | 3.1 | |

| Widowed | 4 | 0.4 | |

| Age at marriage | Less than 20 years | 775 | 69.9 |

| 20–34 years | 333 | 30.1 | |

| Occupation | Housewife | 827 | 73.5 |

| Farmer | 105 | 9.3 | |

| Self-employed | 110 | 9.8 | |

| Employee | 62 | 5.5 | |

| Other | 21 | 1.9 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 415 | 36.9 |

| Grade 1–4 (First cycle) | 125 | 11.1 | |

| Grade 5–8 (Second cycle) | 248 | 22.0 | |

| Grade 9–10 (Third cycle) | 229 | 20.4 | |

| Grade 11–12 and above (PCU and above) | 108 | 9.6 | |

| Husband’s education | Illiterate | 320 | 30.3 |

| Grade 1–4 (First cycle) | 108 | 10.2 | |

| Grade 5–8 (Second cycle) | 205 | 19.4 | |

| Grade 9–10 (Third cycle) | 211 | 20.0 | |

| Grade 11–12 and above (PCU and above) | 213 | 20.1 | |

| Husbands’ occupation | Farmer | 395 | 36.9 |

| Self-employed | 326 | 30.5 | |

| Employee | 212 | 19.8 | |

| Others | 137 | 12.8 | |

| Total births | Less than 3 | 621 | 55.2 |

| 1–3 | 402 | 35.7 | |

| Greater than 5 | 102 | 9.1 | |

| Household size | 2–5 | 801 | 71.2 |

| 6 and above | 324 | 28.8 | |

| Residence | Urban | 387 | 34.4 |

| Rural | 738 | 65.6 | |

| Head of household | Husband | 1060 | 94.2 |

| Wife | 65 | 5.8 |

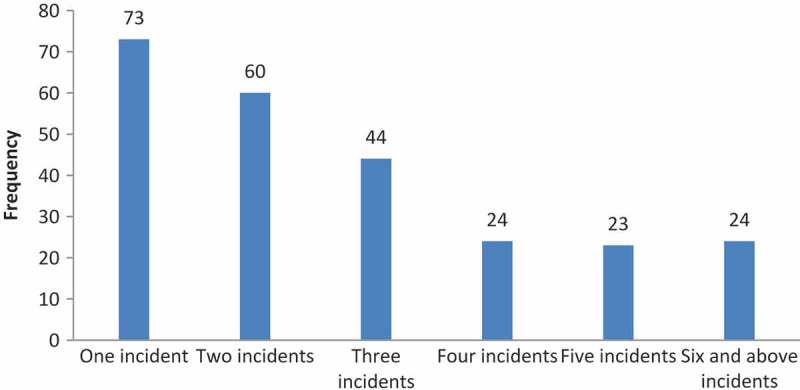

Almost all study participants (1114, 99.1%) reported that they had visited a health institution for antenatal care services in the previous year, and 1031 (91.6%) reported that their last place of delivery was at a health facility. Out of 1125 women, 248 or 22% reported having experienced at least one type of D and A while receiving maternity services in health facilities. About 53% of participants reported that they were shouted at, 44.8% reported having been insulted or scolded and 33.9% reported being ignored when they requested services (Table 2). The majority of women reported two or more incidents (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Women’s experience of D and A during labour and delivery services in Tigray, Ethiopia, 2015.

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D and A during delivery services | |||

| Shouted at | Yes | 132 | 12.5 |

| No | 922 | 87.5 | |

| Scolded/insulted | Yes | 111 | 10.5 |

| No | 943 | 89.5 | |

| Discouraging/became negative to me | Yes | 56 | 5.3 |

| No | 998 | 94.7 | |

| Request for assistance/help ignored | Yes | 84 | 8.0 |

| No | 969 | 92.0 | |

| Not told information before/during a procedure | Yes | 81 | 7.7 |

| No | 973 | 92.3 | |

| Providers discussed my private health information in public | Yes | 9 | 0.9 |

| No | 1045 | 99.1 | |

| Shared my health information with others | Yes | 8 | 0.8 |

| No | 1046 | 99.2 | |

| Was made to lay on unhygienic bed/couch | Yes | 40 | 3.8 |

| No | 1014 | 96.2 | |

| Ashamed for being exposed naked to others | Yes | 17 | 1.6 |

| No | 1037 | 98.4 | |

| Movement restricted for a long time | Yes | 40 | 3.8 |

| No | 1014 | 96.2 | |

| Procedure/s done without being adequately informed | Yes | 67 | 6.4 |

| No | 987 | 93.6 | |

| Left alone unattended | Yes | 63 | 6.0 |

| No | 991 | 94.0 | |

| Hit/slapped/pushed by provider | Yes | 8 | 0.8 |

| No | 1046 | 99.2 | |

| Anything that you do not want to mention | Yes | 2 | 0.2 |

| No | 1052 | 99.8 | |

Figure 1.

Incidents of D and A during labour and delivery in Tigray, Ethiopia, 2015.

In bivariable analyses, the variables religion, ethnicity, marital status, husband’s education, husband’s occupation, and levels of health facilities were dropped because in each case the p-value was > 0.25. Covariates retained for the multivariable analysis were residence, maternal age, maternal education, maternal occupation, total births, household head sex, number of individuals in household, age at marriage, number of antenatal care (ANC) visits for the last pregnancy, duration of labour at facility and permission for support persons to attend labour and delivery.

In the multivariable analysis, D and A during delivery services was reported more among women residing in urban compared with rural areas (aIRR = 1.326; 95% CI: 1.018, 1.727) and women educated to grade 9 or above (aIRR = 1.487; 95% CI: 1.034, 2.139). Similarly, women in the age groups 20–34 (aIRR = 2.674; 95% CI: 1.468, 4.871), and 35 or above (aIRR = 2.892; 95% CI: 1.351, 6.189), compared to those below the age of 20 years, reported more incidents of D and A. Women who were heads of households reported more incidents of D and A (aIRR = 2.024; 95% CI: 1.201, 3.414) compared with women living in a household headed by a male. Women who had 3–5 births experienced fewer incidents of D and A (aIRR = 0.560; 95% CI: 0.318, 0.985) than women with more than 5 births (Table 3).

Table 3.

Negative Binomial Regression estimates of incidence rate ratios of disrespectful and abusive care during labour and delivery with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in Tigray, Ethiopia, 2015.

| Incidence Rate Ratios (Crude) | 95% CIs |

Incidence Rate Ratios (Adjusted) |

95% CIs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| Residence (Reference = Rural) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Urban | 1.626* | 1.339 | 1.976 | 1.326* | 1.018 | 1.727 |

| Age (Reference = Less than 20 years) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 20–34 | 1.988* | 1.251 | 3.161 | 2.674* | 1.468 | 4.871 |

| ≥ 35 | 1.344 | .785 | 2.302 | 2.892* | 1.351 | 6.189 |

| Education (Reference = Illiterate) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Grade 1st–4th | 1.270 | .904 | 1.785 | 1.489 | .980 | 2.263 |

| Grade 5th–8th | 1.280 | .977 | 1.678 | 1.291 | .909 | 1.836 |

| 9th grade and above | 1.931* | 1.527 | 2.442 | 1.487* | 1.034 | 2.139 |

| Occupation (Reference = Housewife) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Farmer | .627* | .427 | .920 | .554 | .189 | 1.626 |

| Self-employed | 1.120 | .816 | 1.537 | 1.213 | .787 | 1.869 |

| Employee | 1.824* | 1.269 | 2.622 | .870 | .608 | 1.245 |

| Other | .884 | .423 | 1.849 | .585 | .332 | 1.032 |

| Total births (Reference = > 5) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <3 | 1.314 | .928 | 1.861 | .864 | .456 | 1.638 |

| 3–5 | 0.797 | 0.550 | 1.156 | 0.560* | 0.318 | 0.985 |

| Household head (Reference = Husband) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Wife | 1.492* | 1.031 | 2.158 | 2.024* | 1.201 | 3.414 |

| Number of individuals in household (Reference = > 5) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2–5 | 1.589* | 1.266 | 1.994 | 1.340 | .905 | 1.984 |

| Age at marriage (Reference = < 20 years) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 20–34 years | 1.638* | 1.341 | 2.001 | 1.009 | .771 | 1.320 |

| Number of ANC visits for the last pregnancy (Reference = ≥ 4 visits) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| One time | 1.641 | .866 | 3.110 | .658 | .206 | 2.097 |

| Two times | 1.042 | .674 | 1.613 | 1.068 | .583 | 1.953 |

| Three times | 1.087 | .874 | 1.351 | 1.259 | .960 | 1.650 |

| Duration of labour at facility(Reference = < 1 hour) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1 to 12 | 1.633* | 1.115 | 2.393 | 1.262 | .834 | 1.910 |

| 13 to 23 | 2.675* | 1.658 | 4.315 | 1.755* | 1.024 | 3.009 |

| 24 hours and more | 4.091* | 1.962 | 8.532 | 2.457* | 1.075 | 5.619 |

| Permission for support persons to attend labour and delivery (Reference = yes) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| No | 2.400* | 1.905 | 3.022 | 1.800* | 1.383 | 2.344 |

Women who spent longer hours in labour in health facilities reported higher rates of D and A. Compared with women who spent less than 1 hour in labour, the adjusted incidence rate ratio for women who spent 13–23 hours in labour was 75% higher (aIRR = 1.755; 95% CI: 1.024, 3.009) and 2.5 times higher for women who spent 24 hours or more in labour (aIRR = 2.457; 95% CI: 1.075, 5.619). Women who were not permitted to have support persons/relatives in the delivery room also reported a significantly higher rate of D and A (aIRR = 1.800; 95% CI: 1.383, 2.344) during labour and delivery compared with those women who were allowed to have support persons (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, a fifth of women reported at least one incident of D and A while attending delivery services. Shouting, insults and ignoring women’s request for assistance were commonly reported types of disrespectful and abusive practices. Residence, women’s education, being the head of a household, the number of births, duration of labour at the health facility, and permission for support persons to attend labour and delivery were significantly associated with incidents of D and A.

In this study, the proportion of women (22%) who reported D and A during labour and delivery is similar to studies conducted in Kenya and Ethiopia [12,16], although lower than that reported in a study conducted in Nigeria (98%) [17]. The commonly reported incidents of D and A in this study were similar to those reported in many from sub-Saharan African countries [13]. These practices are totally unacceptable and unethical. Ignoring women’s requests for help could be very dangerous, leading to life-threatening complications and even death for either (or both) the mother and the baby [18,19].

Lack of information given to women before or during procedures, procedures conducted without their consent, and breach of privacy and confidentiality during childbirth are common practices associated with D and A in sub-Saharan Africa [14,16,20–22]. It is critical that healthcare providers offer women adequate explanation and obtain informed consent from women before administering treatment and performing procedures. These principles conform to fundamental human rights [23]. When women are well informed about the procedures they are required to undergo, their compliance with safety instructions is likely to be higher. They are also more likely to feel respected and come away with positive feelings about their childbirth experiences [9,22].

The proportion of women left unattended during labour (6%) was low in this study compared to that reported in other studies [12,14]. This could well be due to routine performance evaluations that were implemented in health services at the time of this study. Another reason was that the majority of the health institutions in the study also allowed women, but not men, to accompany women in the labour ward [21,23].

Educated women in urban study sites reported more incidents of D and A. Educated women are more knowledgeable about their rights and have higher expectations regarding their healthcare experiences than uneducated women [12,24]. Higher incidents of disrespectful and abusive care were reported from women who had longer labour durations. This may be related to longer observation times in uncomfortable circumstances, which may also cause severe distress and result in negative experiences. Health service users in developing countries generally have insufficient processes in place for appeals, and lengthy labour times provide more opportunities for negative experiences [25]. However, proper incident reporting can lead to improved policies and practices in health facilities and better informed health decision-making by women [26].

Strengths of the study

This community-based study included participants from both rural and urban areas, interviewed outside health facilities. This gave women more freedom to express their feelings and report positive and negative experiences without fear, and eliminated social desirability bias [9]. The use of health extension workers who were known to the women and their communities was a factor in the study achieving a 100% response rate.

Limitations of the study

We acknowledge recall and sampling bias as possible limitations. The recall period in this study was limited to one year in order to minimize recall errors; however, one year could still be considered too long to recall details of incidents that occurred during labour and delivery. There may also have been sampling bias due to the focus on a single encounter in the previous year. Only women who gave birth to live babies were included and therefore the study excluded stillbirths, neonatal and infant deaths. It is possible that those women may have had negative experiences of D and A, but this cannot be established from these data [9].

Women from rural study sites may have under-reported D and A due to their lack of awareness of their rights and having relatively lower expectations than urban women. On the other hand, women referred to a health facility as a result of life-threatening complications may feel gratitude and therefore downplay their reporting of incidents of D and A [9,12,27]. However, we cannot say whether this is true or not from these data.

We did not also include economic status in our analysis because of the large amount of missing data. This was possibly due to women having insufficient information about household income or being unable to report the value of their farm products in monetary terms. Information about facilities and whether there were procedures for reporting D and A was not collected. It is possible that we have underestimated the extent of D and A although we are unable to say whether this is the case.

Conclusions

One in five women reported at least one incident of D and A during labour and delivery. It is important to strengthen accountability mechanisms and enable women to report any violations that occur during their use of health services. Further research is necessary to gain more information about this issue.

Responsible Editor Jennifer Stewart Williams, Umeå University, Sweden

Funding Statement

Mekelle University supported this study financially, and also the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC) under grant number 2016-2018 ADF 011.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Mekelle University and Addis Continental Institute of Public Health for the support provided for this study. This work was financed by Mekelle University and by an African Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship (ADDRF) award offered by African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC). Special thanks to the Tigray Regional Health Bureau and its District Health Offices for facilitating the fieldwork. We also thank all women who participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics and consent

Ethical clearance was secured from Mekelle University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study subjects provided written consent to participate in the study after receiving information about the purpose of the study, risks and benefits, and their rights. Assurance of privacy during the interview and confidentiality of information was given.

Paper context

We conducted a community-based cross-sectional study in northern Ethiopia to investigate the extent of, and factors associated with, disrespectful and abusive maternity care reported by women. One-fifth of women reported disrespect and abuse while giving birth. Urban or educated women reported more incidents of disrespect and abuse. Women who had longer labour duration, and those who were not permitted to have support persons attend their labour and delivery, reported more incidents of disrespect and abuse.

References

- [1]. WHO Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. World Health Organ [Internet] 2014;56 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112682/2/9789241507226_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Daniel E. Identifying and measuring women’s perception of respectful maternity care in public health facilities. A thesis report. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Godefay H, Kinsman J, Admasu K, et al. Can innovative ambulance transport avert pregnancy-related deaths? One-year operational assessment in Ethiopia. J Glob Health 2016;6(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Van Eijk AM, Bles HM, Odhiambo F, et al. Use of antenatal services and delivery care among women in rural western Kenya: a community based survey. Reprod Health. 2006;3:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Mrisho M, Obrist B, Schellenberg JA, et al. The use of antenatal and postnatal care: perspectives and experiences of women and health care providers in rural southern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Graham WJ, Varghese B. Quality, quality, quality: gaps in the continuum of care. Lancet. 2012;379:5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Windau-Melmer TA. Guide for advocating for respectful maternity care. Washington, DC: Futures Group, Health Policy Project; [Internet]; 2013. Available from: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/189_RMCGuideFINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth report of a landscape analysis. Harvard Sch Public Heal Univ Res Co, LLC [Internet] 2010;1–57. Available from: http://www.urc-chs.com/uploads/resourceFiles/Live/RespectfulCareatBirth9-20-101Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [9]. D’Ambruoso L, Abbey M, Hussein J. Please understand when I cry out in pain: women’s accounts of maternity services during labour and delivery in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Center for Reproductive Rights A, Federation of Women Lawyers Failure to deliver: violations of women’s human rights in kenyan health facilities. 2007. Available from: http://www.reproductiverights.org/sites/default/files/documents/pub_bo_failuretodeliver.pdf

- [11]. Changole J, Bandawe C, Makanani B, et al. Patients’ satisfaction with reproductive health services at Gogo Chatinkha Maternity Unit, Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi. (Special section: Reproductive Health). Malawi Med J. [Internet] 2010;22:5–9. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=cagh&AN=20113158733%5Cnhttp://lshtmsfx.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/lshtm?sid=OVID:caghdb&id=pmid:&id=doi:&issn=&isbn=&volume=22&issue=1&spage=5&pages=5-9&date=2010&title=Malawi+Medical+Journa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Abuya T, Warren CE, Miller N, et al. Exploring the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. eBSCOhost. 2015;49:1–13. Available from: http://0-web.b.ebscohost.com.innopac.wits.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=55&sid=1b6b0b8f-fdc0-410f-8222-bfe0c2c33ed0%40sessionmgr114&hid=116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. McMahon SA, George AS, Chebet JJ, et al. Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet] 2014;14:268 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25112432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Asefa A, Bekele D. Status of respectful and non-abusive care during facility-based childbirth in a hospital and health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod Health [Internet] 2015;12:33 Available from: http://www.reproductive-health-journal.com/content/12/1/33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Tigray Regional Health Bureau Nine years performance report on selected core indicators; 1998-2006 EFY. Mekelle (Ethiopia): Dayo Printing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [16]. The last Ten Kilometers (L10K) project Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in four PHCUs in two regions of Ethiopia – Baseline Study Findings. 2014. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Disrespect-and-abuse-during-facility-based-in-four/3f5145440beceff6e35e3c5e3170b402aabf0dd9?tab=citations. [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Okafor II, Ugwu EO, Obi SN. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. Int J Gynecol Obstet [Internet] 2015;128:110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Family Care International Care-seeking during pregnancy, delivery and the postpartum period: a study in Homa Bay and Migori districts, Kenya. New York: FCI; 2005. The Skilled Care Initiative Technical Brief: Compassionate Maternity Care: Provider Communica. [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Pacagnella RC, Cecatti JG, Parpinelli MA, et al. Delays in receiving obstetric care and poor maternal outcomes: results from a national multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet] 2014;14:1–15. Available from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/14/159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Abuya T, Ndwiga C, Ritter J, et al. The effect of a multi-component intervention on disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. Internet. 2015;15:224 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4580125&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Sheferaw ED, Bazant E, Gibson H, et al. Respectful maternity care in Ethiopian public health facilities. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2017;14:60 Available from: http://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-017-0323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Warren C, Njuki R, Abuya T, et al. Study protocol for promoting respectful maternity care initiative to assess, measure and design interventions to reduce disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet] 2013;13:21 Available from: BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Johnson TR. Intensive caring. Int J Gynecol Obs. 2009;104:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Kruk M, Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, et al. Freedm. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: a facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2014; 33(1):e26-e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Gurung G, Derrett S, Gauld R, et al. Why service users do not complain or have “voice”: a mixed-methods study from Nepal’s rural primary health care system. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2017;17:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Ibeneme S, Eni G, Ezuma A, et al. Roads to health in developing countries: understanding the intersection of culture and healing. Curr Ther Res - Clin Exp [Internet] 2017;86:13–18. The Authors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Mesenburg MA, Victora CG, Serruya SJ, et al. Disrespect and abuse of women during the process of childbirth in the 2015 Pelotas birth cohort. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2018;15:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]