“There are few things more embarrassing to a surgeon than the sight of his recently operated patient, his abdomen gaping, and the gut spilling out all around…”

………Moshe Schein

Closing the abdomen after a laparotomy is an important skill that is taught to all surgeons during the initial training period. The skill however takes a while to be understood optimally. There are few facts that are now considered as the “scientific truths” like midline laparotomy, although convenient, bloodless, faster, and popular, is associated with slightly higher rates of burst abdomens and incisional hernias as compared to transverse incisions. Also, that the incisional hernias would have started happening immediately after the closure of abdomen but may take up to 2 years to show up. Although there are many patient-related, surgeon-related, and other miscellaneous factors that play their role in healing of abdominal wall, the understanding of the basic physiology of healing is essential.

The Phases of Fascia Healing [1]

Healing of fascial wounds is a coordinated event of many processes (triggered by tissue injury) and involves three overlapping but well-defined phases:

Inflammation: Lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages take up residence in the wound over the first week after injury, drawn by an array of cytokines and chemokines. The wound becomes edematous, and much of the injured tissue and debris is cleared from the wound by phagocytosis.

Proliferation: Fibroblasts are activated and produce extracellular matrix components. Angiogenesis occurs, and the resulting granulation tissue appears red.

Remodeling: For up to a year after injury, the extracellular matrix is remodeled, helping the wound to regain strength. As the healed tissue matures, fibronectin and hyaluronan are broken down, and collagen bundles increase in diameter, corresponding with increasing tensile strength of the wound. However, these collagen fibers never regain the original strength of unwounded fascia, and at best 80% strength can be achieved.

Initial type III collagen is weaker than the definite scar, type-I collagen [2, 3]. Initial phase of wound healing has type III (weak) collagen (80%) that has low tissue tensile strength and finally definite scar type I (strong) collagen (80%) that has high tissue tensile strength. Initial wound is thus totally dependent on suture for strength [1–3].

Alterations in one or more of these phases would result in wound complications. Although these factors are predominantly patient related, other factors like suture breaks, though rare, are also important and poor judgment or technique is also not rare.

Commandment 1: One Has to Be Thorough with the Basics in Fascia Healing Including Its Anatomy

Fascia is the firm, strong connective tissue that sheaths muscles and is a main supportive structure of the body. Healing of the abdominal wall fascia by around 2 weeks is 20%; by the end of 1 month, it is nearly 50%; at 2 months, 60–80%; and after 1 year, up to 90% healing would have happened. This healing depends on successful wound closure, and after 2–4 weeks, healing fascia begins to have the strength to be self-supporting but is still vulnerable to wound dehiscence. Thus, the abdominal wall attains 52–59% of its original strength in 42 days, 70–80% in 120 days, and 73–93% by 140 days. Maximum strength finally achieved is 93% of the original strength.

Thus, healing fascia requires at least 14 to 28 days before becoming self-supportive. During this time, the wound is completely dependent on the closure device for its initial holding strength. This time is also known as the “critical healing period” and the concept is true for all tissues, though they will have different critical healing periods.

Disruptions in any of the phases of wound healing can lead to wound complications or can result in severely reduced strength of healing fascia.

These disruptions can be localized infection or can be attributed to delayed healing due to patient factors such as diabetes or smoking. The wound is at its weakest at post-operative day 3 [4].

Commandment 2: One Shall Make the Right Incision

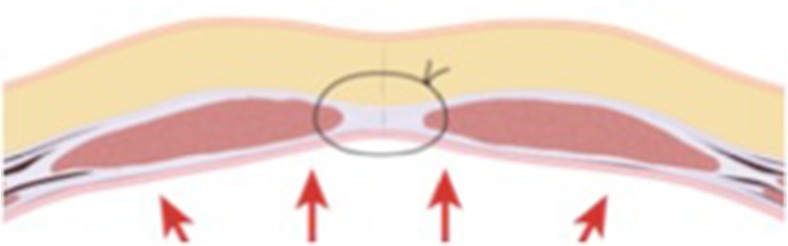

Making right incision forms the basis of a good wound closure. While most agree that midline incisions are associated with increased risk of incisional hernias, these are the most commonly used incisions for ease and speed of access, less bleeding, and subsequent mass closure. This incision also does not involve cutting of any muscle (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The sheath bears the maximum stress of the abdominal wall. Linea alba or the white line is a relatively avascular line for a quick and blood less entry in to the abdomen. Midline laparotomy is therefore the preferred approach

Commandment 3: One Should/Need Not Close the Peritoneum

The peritoneum is a one-cell layer that usually heals as a sheet rather than from the edges. Peritoneum heals itself within 48–72 h and therefore does not need to be sutured. Suturing of peritoneum has been found to be associated with a higher rate of postoperative pain and adhesions. Sheath is the most important layer of the abdominal wall, as it must bear maximum stress on the incision (Fig. 1).

Commandment 4: One Should Use the Right Technique; Surgical Technique Is Only As Good As the Surgeon

One should adhere to basic principles in the technique and surgical technique is only as good as the surgeon. One must not cut corners with the length of the suture and it should be optimum (at least four times the length of the wound). Simple sutures without locking would generally suffice on most occasions but should not be too tight (strangulation of the tissue). This has also been observed that the length of abdominal incision increases up to 30% in postoperative period. Therefore, 4:1 suture to wound length ratio will allow adequate bites and would also avoid cutting through the fascial sheath.

“If it looks all right, it’s too tight—if it looks too loose, it’s all right”

……….Matt Oliver

Commandment 5

One should deploy a safe technique that is fast, easy, cost effective, and associated with minimal early or late complications. The continuous suture is associated with greater tensile strength when compared to interrupted one. Layered closure has been shown to have wound dehiscence rates of 11% as compared to 1% with mass closure technique. Layered closure also consumes more time. Statistically significant reduction in hernia and dehiscence rates has been observed with mass closure technique [4].

Commandment 6

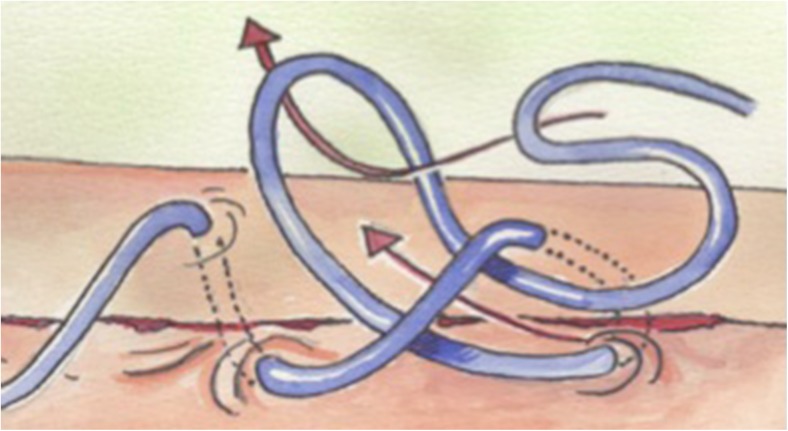

One should use mass closure technique based on Jenkins’s rule (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mass closure technique involves continuous suturing with a minimum width of 1 cm and not more than 1 cm away from the previous bite

The “spring coil effect theory” of Jenkins revolutionized the concept of abdominal wound closure especially following a midline laparotomy. It is based on the concept of closure of aponeurosis using continuous bites (without locking) at a width of more than 1 cm and not more than 1 cm away from the previous bite (“1x1 cm without locking and tension”), in the end producing a spring coil that would accommodate the wound distension in the immediate postoperative period. This spring coil also promotes healing with type I collagen that is present around 1 cm away from the edge of the rectus sheath. There is however no consensus on the surgical technique [5].

Commandment 7: One Would Use the Right Suture

An ideal suture as defined by Sir Moynihan should be “absorbable, non reactive, easily available, cheap and easy to handle for knotting purposes etc.”. Needless to say, such a suture does not exist. There are however monofilament “synthetic” absorbable as well as non-absorbable sutures that are close to being ideal. The suture should be tailored to the tissue, its tensile strength and the support that it needs to heal optimally. It is generally accepted that non-absorbable sutures cause less tissue reaction and are more resistant to infection than the absorbable sutures. However, these sutures are associated with higher incidence of buttonhole hernias and sinus formation leading to increased wound pain. A study comprising of 12 centers reporting about the closure tactics following elective laparotomies showed no consensus on the type of suture material to be used [4].

Commandment 7: One Should Follow Recommendations Regarding the Suturing and Knotting Techniques

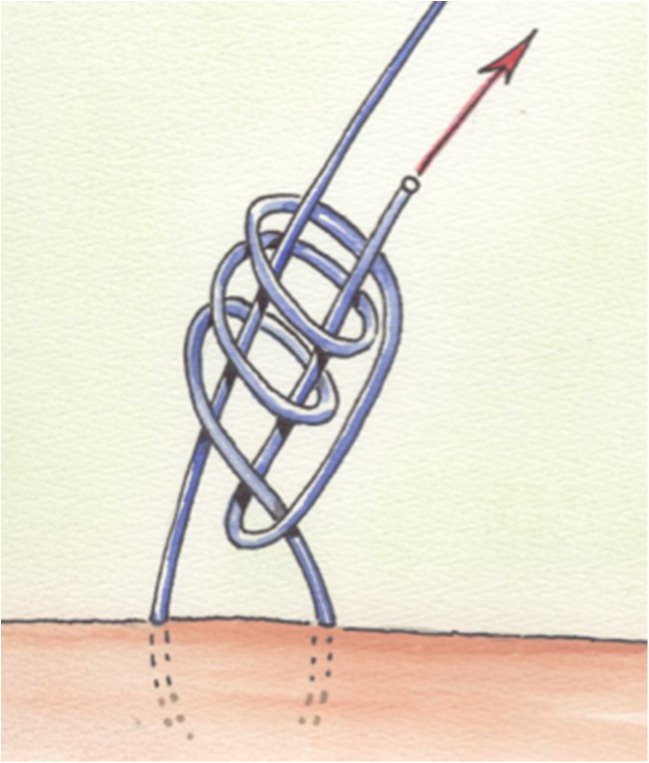

Monofilament suture material, 2/0 slowly absorbable or non-absorbable mounted on small needle, should be deployed as continuous sutures without any locking. The suture would terminate with self-locking anchor knots (Figs. 2 and 3). Continuous suture when used in one layer avoids high tension on suture and does not compress the wound edges. This prevents devascularization of the sheath and formation of a good quality collagen, i.e., type I.

Fig. 3.

The self-locking knot

Commandment 8: Shall Use Good Knotting Techniques [6]

Self-locking knots or an Aberdeen knot is a very effective and frequently used knot in view of high knot security, efficiency, and minimal volume. This knot is also known for not slipping and has minimal effect on suture strength unlike the conventional reef or square knot in this scenario (Fig. 3).

Commandment 9: One Should Not “always” Close the Abdomen—Shall not stuff a living Turkey [7]

All abdomens should not be closed, especially if there is associated tension. Also, if there is intraperitoneal contamination or more importantly if the patient has poor APACHE-II scores, one needs to understand that the physiological changes produced as a result of intra-abdominal hypertension (even if transient) are often irreversible. One has to rely on objective scoring rather than gut feeling and subjective assessment to make a decision regarding closing or leaving the abdomen open. The author likes to rely on APACHE-II scoring system to triage the patients in to high-, moderate-, and low-risk groups. As a protocol, the abdomens of patients with poor APACHE-II scores are not closed and these should be managed as laparostomies [7–9].

Commandment 10: One Should Not Use “tension band sutures” to Close the Abdomen

The age old practice of using tension sutures when dehiscence is anticipated should not be encouraged and in fact should not be used. There is a risk of producing “bow string” damage to the bowel coming in contact with these tight sutures and also the fact that associated tension may actually hurt the cause. Every abdomen can/should not be closed. In the event of peritoneal sepsis, poor sepsis scores/APACHE scores, it is not wise to close the abdomen as it would open up on its own but not before setting up a sequence of events leading to an irreversible physiological damage. Such abdomens are better managed as open abdomens or laparostomies with or without any zippers [7–9].

References

- 1.Ramshorst V, et al. Abdominal wound dehiscence in adults. World J Surg. 2010;34(1):20–27. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0277-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Höer J, Junge K, Schachtrupp A, Klinge U, Schumpelick V. Influence of laparotomy closure technique on collagen synthesis in the incisional region.Hernia. 2002 Sep;6(3):93-8. Epub 2002 Jul 20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Hawley PR, Hunt TK, Dumphy JE. Etiology of colonic anastomotic leaks. Proc R Soc Med. 1970;63(Suppl 1):28–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rath AM, Chevrel JP (Am J Surg 1992, 1987) The healing of laparotomies: a review of the literature. Part 1. Physiologic and pathologic aspects. 1:727

- 5.Chintamani, et al. Technique related issues—Indian scenario. Indian J Surg. 2012;74(3):213–216. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Israelsson LA, Jonnson T. Physical properties of self locking and conventional surgical knots. Eur J Surg. 1994;160:323–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chintamani, Bhatnagar D. The role of APACHE-II triaging in optimum management of small bowel perforations & wound closure. Trop Dr. 2001;31(4):198–201. doi: 10.1177/004947550103100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chintamani, Singhal V. Urobag zipper laparostomy in intraperitoneal sepsis. Trop Doct. 2003;33(2):123–124. doi: 10.1177/004947550303300230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chintamani, Singhal V. Temporary closure of open abdominal wounds by the modified sandwich-vacuum pack technique—letter. Br J Surg. 2003;90:718–722. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]