Abstract

Introduction:

Urinary schistosomiasis caused by Schistosoma haematobium is common in some parts of Lusaka Province, Zambia, where water contact activity is high and sanitation is poor. We conducted a longitudinal study in Ng'ombe Compound of Lusaka, between 2007 and 2015, to observe the prevalence and intensity of S. haematobium infection among community primary school children, before and after receiving a single dose of praziquantel.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 975 (445 females and 530 males) pupils, aged 9–16 years, were tested for S. haematobium at baseline. After mass treatment with praziquantel in 2010, 1570 pupils (785 females and 785 males), aged 9–15 years, were examined for S. haematobium eggs, from 2011 to 2015.

Results:

At baseline, 279 out of 975 of the children were infected, with light infections constituting 84.9% and 15.1% classified as heavy infection. After mass treatment with praziquantel, the prevalence rate dropped, slightly, to 20.3% (63 out of 310) in 2011. However, it increased the following years up to 38% (133 out of 350) in 2015, with prevalence rates higher in males than females. The average number of heavy infection cases increased to 24.3% (120 out of 494) after treatment, reducing cases of light infections to 75.7% (374 out of 494).

Conclusion:

This study revealed that mass treatment with a single dose of praziquantel was not sufficient to significantly reduce the transmission of schistosomiasis. Further studies will need to evaluate whether multiple praziquantel treatments will be more therapeutically effective in limiting future incidences.

Keywords: Intensity, neglected tropical disease, praziquantel, prevalence, Schistosoma haematobium, schistosomiasis

INTRODUCTION

Schistosomiasis (commonly known as bilharzia) is a neglected tropical disease that affects about 258 million of the world population per annum, most of whom live in the tropical and subtropical regions of the globe.[1] Despite its high morbidity, the disease is often not incorporated in national health programs of most developing countries as the mortality rate attributed to schistosomiasis is low and occurs after prolonged infection. In Zambia, over two million people are infected with schistosomiasis with children accounting for >60%.[2] Two species of Schistosoma common in this country are Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni.[3,4] The freshwater snails of genera Bulinus and Biomphalaria serve as intermediate hosts for S. haematobium and S. mansoni, respectively.[5] This ties transmission of the disease to places where people and snails (that release cercariae) come together at the same water habitat.[6,7] Hence, schistosomiasis tends to be commonly found in different communities where contact with fresh water bodies can be a routine and inevitable occurrence.

Schistosomiasis infection can result in severe illness, disability, and death.[8] Some forms of the disease have also been linked to hepatitis,[9,10] cancer,[11,12] and HIV/AIDS.[13] Chronic schistosomiasis can also lead to renal dysfunction.[14,15] In addition, inflammation and ulceration in the bladder mucosa lead to hematuria and dysuria,[16] which may eventually lead to anemia. The disease, even when not associated with other infections, affects the physical and mental development of children and greatly diminishes the strength and production power of adults. It is estimated that the disease lowers the productivity of the population by 33%.[17]

In Zambia, the Ministry of Health in conjunction with the Ministry of Education, under the Zambia Bilharzia Control Program, has carried out mass treatment of pupils with a single dose of praziquantel, at least once a year in different community primary schools. In Ng'ombe Compound of Lusaka, the drug was given to the children in 2010, but no posttreatment follow-ups were made to evaluate the effectiveness of the drug. In addition, the sources of schistosomiasis infection (water bodies) were not surveyed. Therefore, we conducted this study to access the prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis in school-going children in Ng'ombe before and after treatment with praziquantel. The aim of this study was to observe the trend of urinary schistosomiasis and determine whether the intervention was effective or not.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study area

Ng'ombe Compound is an area of about 0.934 km2 and is situated to the Northeast of Lusaka City in Zambia. This area was selected based on the previous history of schistosomiasis infection which was reported to be in the range of 20%–40%.[18] A census of the population in 2010 reported that the population of Ng'ombe was 45 733 with a total of 9417 households. Out of this population, 49% or about 22,409 were children below the age of 16 years. Sanitation in this area is poor. The compound is surrounded by the Chamba Valley stream which harbors the snails Bulinus globosus that act as intermediate hosts of S. haematobium. This 3 km long stream is the major source of water for human activities including recreation activities for children resulting in their exposure to cercarial Schistosoma.

Study participants and specimen collection

Since S. haematobium is more common in young age groups, the target population for this study was school-going children below the age of 16 years in Ng'ombe Compound. Four community primary schools were selected at random. These were Flying Angel, Ng'ombe PTA, ZOCS, and Presbyterian Schools. Consent was obtained 3 months prior from the parents through the school teachers and assent was obtained from all the children included in the study. Children from grades 1–5 were included in this study. Grades 6 and 7 are usually crucial years for standardized exams; thus, children in these grades were excluded from the study. The children were interviewed to obtain their name, age, sex, distance of home to the stream and water contact activities. The data were recorded on a collection form that was kept confidential. Each child was assigned a number that was written on a clean bottle given to the child. The children were instructed to provide the last portion of their urine to optimize the egg collection. All urine samples were collected before noon. Two drops of 10% formyl saline were added to each urine sample to preserve any S. haematobium eggs that may have been present. The urine samples were then transported to the University of Zambia, Biological Sciences laboratory for examination on the same day of urine collection. Diagnosis was based on the detection of eggs of S. haematobium in 10 ml of urine specimen. The filtration method described by Mott et al.[19] was used for processing all urine specimens. One microscope slide was prepared from each urine specimen and then examined microscopically at ×10 and ×40 objectives. If positive, the number of eggs in the entire sample of 10 ml of urine was counted and recorded as light infection if <30, or heavy infection if >30 eggs.[20] This study was carried out from 2011 to 2015, after mass treatment with praziquantel in 2010.

Use of epidemiological data

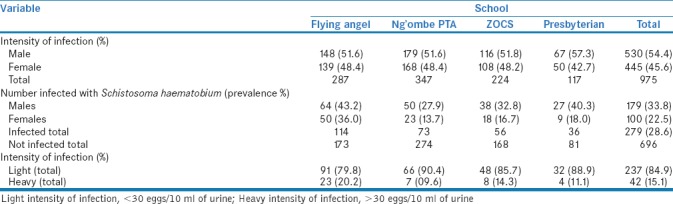

Epidemiological data on the prevalence and intensity of S. haematobium obtained in 2007[18] before treatment with praziquantel were used as the baseline for the present study. Prevalence and intensity data during 2007 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence and intensity of Schistosoma haematobium in 2007 in the four primary schools before treatment

Posttreatment surveys

Five longitudinal surveys were conducted to obtain basic data on the prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis, after treatment of all school-going children with praziquantel in the study area. The first survey was conducted in 2011 and was repeated every year up to 2015 to follow up the impact of targeted mass treatment with praziquantel, given to all school-going children by Ng'ombe Health Centre Workers in 2010. The number of urine samples collected in each year was dependent on the availability of pupils in each school. A total of 1570 pupils (785 females and 785 males), aged 9–15 years, were enrolled for the study from the four schools.

Ethical approval

The study was approved and reviewed by the University of Zambia Biochemical Research and Ethics committee and is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. The parents of children who tested positive for bilharzia were encouraged to take the children to Ng'ombe Health Center for further testing and treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data were double entered and analyzed in Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 6 from (GraphPad Software Inc, USA). The Chi-square test was used to compare differences in prevalence rates between males and females. The reduction in prevalence of S. haematobium 1 year after treatment was calculated as outlined below.[21]

Prevalence Reduction = (% baseline prevalence − % prevalence 1 year after treatment/% baseline prevalence) ×100%

RESULTS

Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium before mass treatment

Table 1 summarizes the prevalence and intensity of S. haematobium infections in 2007 before the intervention. A total of 279 out of 975 or 28.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 25.8–31.5) of the children were infected. The overall rate of light infection with S. haematobium was observed in 237 out of 696 or 84.9% (95% CI = 80.8–89.1) of the infected individuals, whereas 42 (15.1%) were heavily infected. The average prevalence rate in males was higher than in females (P = 0.0001 using Chi-square test).

Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium post mass treatment

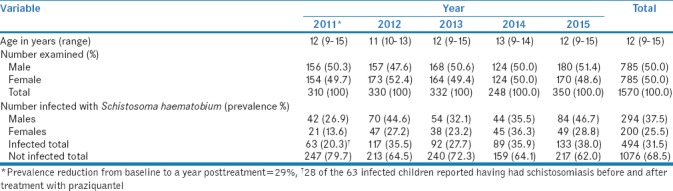

Table 2 summarizes a summary of age, gender, and prevalence of S. haematobium from 2011 to 2015, in school-going children from Ng'ombe Compound after receiving treatment with praziquantel in 2010. The prevalence rate reduced to 20.3% with 95% CI = 15.8–24.8 (63 out of 310) after treatment but began to increase steadily and up to 38% with 95% CI = 32.9–43.1 (113 out of 217) in 2015. The average prevalence rate was 31.5% with 95% CI = 29.2–33.8 (494 out of 1570) for S. haematobium form. When stratified by gender, the overall prevalence of S. haematobium was higher in males than in females [Table 2]. Using Chi-square test at probability 0.05, there was a statistical significance difference in infection rates between males and females for the years 2011 (P = 0.004), 2012 (P 0.001), and 2015 (P = 0.001). However, in 2013 (P = 0.068) and 2014 (P = 0.895), the difference in infection rate between males and females was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium infection in four community school children after treatment with praziquantel

Intensity of Schistosoma haematobium

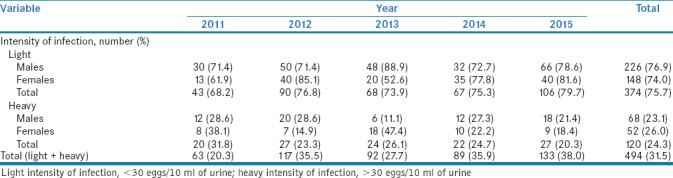

Table 3 summarizes the intensity of infection with S. haematobium posttreatment. Light infection was observed in 374 of the 494 (75.5% with 95% CI = 72.1–79.7) infected children, whereas 120 (24.3% with 95% CI = 20.5–28.1) had egg counts >30 eggs per 10 ml of urine and were categorized as heavy infections. A number of light infection cases were higher than cases of heavy infections throughout the 5-year period, as depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intensity of Schistosoma haematobium infection in four community school children after treatment with praziquantel

DISCUSSION

This study revealed varied rates of both prevalence and intensity of infection with S. haematobium from 1 year to another. Administration of praziquantel in 2010 resulted in the prevalence reduction of only 29% the following year. However, the prevalence rate increased after 2011 up to 38% in 2015, closely resembling the prevalence rate at baseline (28.6% in 2007). These results suggest that a single dose of praziquantel was not sufficient to maintain low levels of schistosomiasis over a long period of time. A study in Yemen also reported that treatment with praziquantel alone was not sufficient to significantly reduce the prevalence of S. haematobium in endemic areas.[22] In addition, another study observed that yearly chemotherapeutic intervention did not dramatically change the prevalence nor the intensity of infection in many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.[23]

Similar to what was reported in Ghana,[24] Ethiopia,[25] Nigeria,[26] Benin,[27] and Senegal,[28] our study revealed that boys are more commonly infected than girls of the same age. This observation may perhaps be explained by the greater mobility of males. Boys who are mobile, for reasons relating to their pastime, will frequently encounter S. haematobium cercariae more than girls. Thus, the females will be less intensively exposed to infection and will have virtually less numbers of schistosome worms.

The intensity describes the parasitic load and can be measured by the number of eggs excreted. It is considered to be directly related to the morbidity of schistosomiasis.[29] Before treatment with praziquantel, the overall rate of light infection was much higher than that of heavy infection. This means that a low proportion of children were carriers of heavy load. This trend is common in many studies[30,31,32] although a few studies[33,34] reported instances where carriers of heavy infection were significantly higher than carriers of low infection. Five years after mass treatment, the overall rate of light infection reduced, whereas the rate of heavy infection increased. This indicates that a relatively higher proportion of children became carriers of heavy infection after treatment with praziquantel, suggesting that one-time chemotherapy might shift intensity of schistosomiasis. Taken together, our results indicate that reduction of transmission by short-term chemotherapy alone seems to be very difficult to achieve.

As the Chamba Valley stream offers the only available source of water, the local population of Ng'ombe, including children, is all potentially exposed to infection. Bulinus (Physopsis) globosus snails which act as intermediate hosts have been found in Chamba Valley stream at several points.[18] The transmission of urinary schistosomiasis could be introduced into the stream by other infected nonschool-going children in the community who were not treated at Ng'ombe Health Centre. This could happen through their water contact activities such as swimming. Thus, the discharge of more new eggs of Schistosoma parasite, especially from those with heavy infection, would infect existing snails that then shed more cercariae, which in turn reinfect even the previously treated school children. Rapid reinfection could be responsible for increasing the prevalence rate and carrying the intensity rate after treatment. Indeed, the re-infection rate for schistosomiasis in the children sampled from Ng'ombe compound was as high as 44% in 2012. This suggests that close to half of the children that get treated may still contract the disease by the following year. However, caution may be applied in interpreting this reoccurrence rate since several studies have shown that praziquantel rarely achieves a 100% cure rate.[35,36,37,38,39] Therefore, some cases that were counted as re-infections may be old cases of schistosome infection from the previous years.

Generally, two or more egg counts improve the estimation of the prevalence and intensity of infection when the filtration method is used. However, due to limited resources, single egg counts were used to estimate the prevalence and intensity of S. haematobium. Therefore, it is possible that burden of urinary schistosomiasis, especially light intensity of infection, in Ng'ombe Compound may be higher than what we have reported in this study. Future studies would include analyzing the immunology cell profile of children who have been treated with praziquantel more than once in this population. This would greatly contribute to the understanding of re-infection of schistosomiasis in endemic areas.

CONCLUSION

As long as transmission continues, chemotherapy would have to be repeated indefinitely. Complete eradication of schistosomiasis may be next to impossible, provided poor sanitary conditions persist, but control can significantly reduce the prevalence rates. Ideally, every re-infection should be treated at a community level; this is obviously costlier and may not be realistic. Although chemotherapy is considered as a measure for reduction of human morbidity in Schistosomiasis, it is certainly not the only public health intervention of value. Control of Schistosomiasis requires an integrated approach with the use of health education, water supply, sanitation, and focal mollusciciding, which are all important components of Schistosomiasis control.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Department of Biological Sciences, School of Natural Sciences, The University of Zambia.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Technical Staff at Department of Biological Sciences, School of Natural Sciences, The University of Zambia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bamgbola OF. Urinary schistosomiasis. Pediatr Nephrol (Berlin, Germany) 2014;29:2113–20. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2723-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agnew-Blais J, Carnevale J, Gropper A, Shilika E, Bail R, Ngoma M, et al. Schistosomiasis haematobium prevalence and risk factors in a school-age population of peri-urban Lusaka, Zambia. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:247–53. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ZBCP. Baseline Survey for Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis. Lusaka, Zambia: Ministry of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutengo MM, Mwansa JC, Mduluza T, Sianongo S, Chipeta J. High Schistosoma mansoni disease burden in a rural district of Western Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:965–72. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Eeden JA, Brown DS, Oberholzer G. The distribution of freshwater molluscs of medical and veterinary importance in south-eastern africa. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1965;59:413–24. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1965.11686327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colley DG, Secor WE. Immunology of human schistosomiasis. Parasite Immunol. 2014;36:347–57. doi: 10.1111/pim.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCreesh N, Booth M. The effect of simulating different intermediate host snail species on the link between water temperature and schistosomiasis risk. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chitsulo L, Loverde P, Engels D. Schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:12–3. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rakotonirina EJ, Andrianjaka P, Rakotoarivelo RA, Ramanampamonjy RM, Randria MJ, Rakotomanga JD, et al. Relation between Shistosoma mansoni and hepatosplenomegalies. Sante. 2010;20:15–9. doi: 10.1684/san.2009.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lubeya M, Muloshi C, Baboo KS, Sianongo S, Kelly P. Hepatosplenic schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2010;376:1645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botelho MC, Alves H, Richter J. Estrogen metabolites for the diagnosis of schistosomiasis associated urinary bladder cancer. SM tropical medicine journal. 2016;1:1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardo C, Cunha MC, Santos JH, da Costa JM, Brindley PJ, Lopes C, et al. Insight into the molecular basis of Schistosoma haematobium-induced bladder cancer through urine proteomics. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:11279–87. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4997-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Means AR, Burns P, Sinclair D, Walson JL. Antihelminthics in helminth-endemic areas: Effects on HIV disease progression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD006419. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006419.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duarte DB, Vanderlei LA, de Azevêdo Bispo RK, Pinheiro ME, da Silva GB, Junior, De Francesco Daher E, et al. Acute kidney injury in schistosomiasis: A retrospective cohort of 60 patients in Brazil. J Parasitol. 2015;101:244–7. doi: 10.1645/13-361.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morenikeji OA, Eleng IE, Atanda OS, Oyeyemi OT. Renal related disorders in concomitant Schistosoma haematobium-plasmodium falciparum infection among children in a rural community of Nigeria. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9:136–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ephraim RK, Abongo CK, Sakyi SA, Brenyah RC, Diabor E, Bogoch II, et al. Microhaematuria as a diagnostic marker of Schistosoma haematobium in an outpatient clinical setting: Results from a cross-sectional study in rural Ghana. Trop Doct. 2015;45:194–6. doi: 10.1177/0049475515583793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organisation. Measurement of the Public Importance of Bilharziasis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shehata MA. Prevalence of Urinary Schistosomiasis and Snail Survey in Ng'ombe Compound, Lusaka. In: Zambia TU, editor. First International Multi-Discipline Conference on Recent Advances in Research; Lusaka, Zambia. Lusaka, Zambia: The University of Zambia; 2007. pp. 145–59. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mott KE, Baltes R, Bambagha J, Baldassini B. Field studies of a reusable polyamide filter for detection of Schistosoma haematobium eggs by urine filtration. Tropenmed Parasitol. 1982;33:227–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed AM, Abbas H, Mansour FA, Gasim GI, Adam I. Schistosoma haematobium infections among schoolchildren in central sudan one year after treatment with praziquantel. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:108. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montresor A, Crompton DW, Hall A, Bundy DA, Savioli L. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis and Schistosomiasis at Community Level: A Guide for Managers of Control Programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 1998. p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdulrab A, Salem A, Algobati F, Saleh S, Shibani K, Albuthigi R, et al. Effect of school based treatment on the prevalence of schistosomiasis in endemic area in Yemen. Iran J Parasitol. 2013;8:219–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doenhoff MJ, Hagan P, Cioli D, Southgate V, Pica-Mattoccia L, Botros S, et al. Praziquantel: Its use in control of schistosomiasis in Sub-Saharan Africa and current research needs. Parasitology. 2009;136:1825–35. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayeh-Kumi PF, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Baidoo D, Teye J, Asmah RH. High levels of urinary schistosomiasis among children in Bunuso, a rural community in Ghana: An urgent call for increased surveillance and control programs. J Parasitic Dis. 2015;39:613–23. doi: 10.1007/s12639-013-0411-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geleta S, Alemu A, Getie S, Mekonnen Z, Erko B. Prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis and associated risk factors among abobo primary school children in Gambella Regional State, Southwestern Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:215. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0822-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ojurongbe O, Sina-Agbaje OR, Busari A, Okorie PN, Ojurongbe TA, Akindele AA. Efficacy of praziquantel in the treatment of Schistosoma hematobium infection among school-age children in rural communities of Abeokuta, Nigeria. Infect Dis Poverty. 2014;3:30. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-3-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibikounle M, Ogouyemi-Hounto A, de Tove YS, Dansou A, Courtin D, Kinde-Gazard D, et al. Epidemiology of urinary schistosomiasis among school children in Pehunco area, Northern Benin. Malacological survey. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2014;107:177–84. doi: 10.1007/s13149-014-0345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senghor B, Diallo A, Sylla SN, Doucouré S, Ndiath MO, Gaayeb L, et al. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis among school children in the district of Niakhar, region of Fatick, Senegal. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooppan RM, Schutte CH, Mayet FG, Dingle CE, Van Deventer JM, Mosese PG, et al. Morbidity from urinary schistosomiasis in relation to intensity of infection in the natal Province of South Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35:765–76. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bocanegra C, Gallego S, Mendioroz J, Moreno M, Sulleiro E, Salvador F, et al. Epidemiology of schistosomiasis and usefulness of indirect diagnostic tests in school-age children in Cubal, central Angola. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amuta EU, Houmsou RS. Prevalence, intensity of infection and risk factors of urinary schistosomiasis in pre-school and school aged children in Guma Local Government Area, Nigeria. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7:34–9. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Midzi N, Mduluza T, Chimbari MJ, Tshuma C, Charimari L, Mhlanga G, et al. Distribution of schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminthiasis in Zimbabwe: Towards a national plan of action for control and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senghor B, Diaw OT, Doucoure S, Sylla SN, Seye M, Talla I, et al. Efficacy of praziquantel against urinary schistosomiasis and reinfection in senegalese school children where there is a single well-defined transmission period. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:362. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0980-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jukes MC, Nokes CA, Alcock KJ, Lambo JK, Kihamia C, Ngorosho N, et al. Heavy schistosomiasis associated with poor short-term memory and slower reaction times in Tanzanian schoolchildren. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:104–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trainor-Moss S, Mutapi F. Schistosomiasis therapeutics: Whats in the pipeline? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9:157–60. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.1102051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenwick A. Praziquantel: Do we need another antischistosoma treatment? Future Med Chem. 2015;7:677–80. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kramer CV, Zhang F, Sinclair D, Olliaro PL. Drugs for treating urinary schistosomiasis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;8:Cd000053. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000053.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keiser J, Silué KD, Adiossan LK, N'Guessan NA, Monsan N, Utzinger J, et al. Praziquantel, mefloquine-praziquantel, and mefloquine-artesunate-praziquantel against Schistosoma haematobium: A randomized, exploratory, open-label trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaula SA, Tarimo DS. Impact of praziquantel mass drug administration campaign on prevalence and intensity of Schistosoma haemamtobium among school children in Bahi district, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2014;16:1–8. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v16i1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]