Abstract

Background & objectives:

Invasive cervical cancer patients are primarily treated with chemoradiation therapy. The overall and disease-free survival in these patients is variable and depends on the tumoral response apart from the tumour stage. This study was undertaken to assess whether in vivo changes in gene promoter methylation and transcript expression in invasive cervical cancer were induced by chemoradiation. Hence, paired pre- and post-treatment biopsy samples were evaluated for in vivo changes in promoter methylation and transcript expression of 10 genes (ESR1, BRCA1, RASSF1A, MYOD1, MLH1, hTERT, MGMT, DAPK1, BAX and BCL2L1) in response to chemoradiation therapy.

Methods:

In patients with locally advanced invasive cervical cancer, paired pre- and post-treatment biopsies after 10 Gy chemoradiation were obtained. DNA/RNA was extracted and gene promoter methylation status was evaluated by custom-synthesized methylation PCR arrays, and the corresponding gene transcript expression was determined by absolute quantification method using quantitative reverse transcription PCR.

Results:

Changes in the gene promoter methylation as well as gene expression following chemoradiation therapy were observed. BAX promoter methylation showed a significant increase (P< 0.01) following treatment. There was a significant increase in the gene transcript expression of BRCA1 (P< 0.01), DAPK1 and ESR1 (P< 0.05), whereas MYOD1 and MLH1 gene transcript expression was significantly decreased (P< 0.05) following treatment.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The findings of our study show that chemoradiation therapy can induce epigenetic alterations as well as affect gene expression in tissues of invasive cervical cancer which may have implications in determining radiation response.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, chemoradiation therapy, gene transcript expression, methylation PCR arrays, promoter methylation

Locally advanced invasive cervical cancer is treated by chemoradiation therapy that involves administration of chemotherapeutic agent concurrently with radical radiation therapy1. Cisplatin is the commonly used chemotherapeutic agent in the case of cervical cancer which sensitizes the tumour cells to radiation therapy by inducing DNA damage1,2. Although chemoradiation therapy has significantly improved the outcome of patients with invasive cervical cancer, response to treatment is variable and difficult to predict within a given tumour stage. It is well known that chemotherapy as well as radiation therapy induces cell death and is also associated with inhibition of cell proliferation and decreased cell survival3. Ionizing radiation (IR) induces DNA damage by the disruption of many signal transduction cascades responsible for maintaining cellular homeostasis and the interactions between the cells and extracellular matrix resulting in cell death which usually takes place by apoptosis4,5. However, the exact molecular mechanisms and the determinants of radiation response intrinsic to the tumour are not well understood and hence there is a need for identifying markers (genetic and epigenetic), which can prognosticate and predict the response of a given patient6. In an in vitro study on HeLa and SiHa cells, we have previously shown that cisplatin modulates methylation pattern and gene expression of various genes, thereby affecting response to chemotherapy7. Hence, we designed this pilot study to evaluate in vivo changes in the methylation and gene expression profiles in response to chemoradiation therapy in patients with locally advanced invasive cervical cancer. For this study genes involved in DNA repair (BRCA1, MLH1, MGMT and DAPK1), apoptosis (BAX and BCL2L1), tumour suppressors (RASSF1A) and others (hTERT, MYOD1 and ESR1) were selected. All these genes have been shown to be hypermethylated with a frequency of methylation ranging from 20 to 70 per cent in invasive cervical cancer excluding genes which showed a very high or a very low frequency of promoter methylation8,9,10,11,12,13. In our previous study on a large group of cervical cancer patients unmethylated MYOD1, unmethylated ESR1 and methylated hTERT promoters as well as lower ESR1 transcript levels were shown to predict chemoradiation resistance14. The patients included in this study were from a subset of the cohort wherein paired biopsies prior to and following 10 Gy chemoradiation treatment were evaluated.

Material & Methods

This study was carried out after approval by the Institute's Ethics Committee (vide letter no. 7985/PG/1Trg/09/10242) in the Molecular Pathology Laboratory, department of Cytology and Gynecological Pathology, in collaboration with the departments of Gynaecology and Obstetrics and Radiotherapy and Oncology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. Patients were recruited voluntarily from 2009 to 2011 after obtaining an informed written consent, and the experiments were carried out in 2014-2015.

A total of 20 patients (age range: 34-65 yr, mean age: 49.8±8.55) were included in the study. All patients were histologically proven cases of invasive squamous cell carcinoma, non-keratinizing type. A small portion of the routine pre-treatment cervical biopsy performed for histopathological diagnosis was snap frozen and stored at −80°C. The paired post-chemoradiation therapy sample was obtained after 10 Gy radiation. This dose of 10 Gy was chosen in light of previous studies that have shown peak apoptosis to occur with 9 Gy radiation and tissue necrosis at higher radiation doses when molecular evaluation is not possible11,15. The chemoradiation protocol consisted of 40 mg/m2 cisplatin along with 10 Gy radiation in five fractions given in the first week; following this, a biopsy was obtained from the tumour. After confirmation of the histopathological diagnosis and evaluation of touch imprint smear to confirm that it contained at least 70 per cent tumour tissue, the samples were subjected to molecular analysis.

Treatment protocol and follow up: All patients were in FIGO (International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics) Stage IIB/III (7 patients were in Stage IIB and 13 were in Stage III) and were treated identically with chemoradiation therapy. The patients were administered with 46 Gy in 23 fractions external beam radiation concurrently with 40 mg/m2 cisplatin weekly dose with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy using a four-field box technique followed by intracavitary brachytherapy (two fractions of 9 Gy high-dose rate delivered one week apart). All patients were followed up clinically with relevant clinical and radiological investigations performed during the follow up which included haemogram, detailed clinical examination, biochemical evaluation including renal and liver function tests, ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scan of pelvis, abdomen and chest. All patients were followed up every two months for the first year, every three months until five years and six months after five years. Patients without pelvic control within the radiation portals were considered as locoregional failures [local evidence of disease (LED)] which included patients with residual cervical disease and/or presence of pelvic lymph nodes while on treatment or recurrence, which occurred 1-18 months after completion of the chemoradiation protocol. The remaining patients who were disease free [no evidence of disease (NED)] on follow up ranging from 36 to 60 months after completion of the chemoradiation protocol were considered chemoradiation sensitive.

The effect of chemoradiation therapy on gene promoter methylation and transcript levels of ESR1, BRCA1, RASSF1A, MYOD1, MLH1, hTERT, MGMT, DAPK1, BAX and BCL2L1 genes was evaluated by comparing pre-treatment sample with a second post-treatment sample obtained after 10 Gy chemoradiation treatment. The gene promoter methylation status was evaluated as percentage methylation using methylation PCR arrays. The transcript copy numbers were derived by absolute quantification using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR).

DNA/RNA extraction: DNA/RNA was extracted from the tissue samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following manufacturers’ instructions and were stored at −80°C till further analysis.

Gene promoter methylation analysis by methylation PCR arrays: The percentage methylation of the gene promoter was analyzed by the EpiTect Methyl II PCR Array (SABiosciences Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following manufacturer's instructions. DNA (1 μg) was mixed with 26 μl of 5× Restriction digestion buffer and RNase/DNase-free water was added to make a final volume of 120 μl. The reaction was further divided into four separate reaction tubes, each tube containing 28 μl of the above mix and the tubes were labelled as Mo, Ms, Md and Msd. To Mo, no enzyme was added, 1 μl methylation-sensitive enzyme A was added to Ms, 1 μl methylation-dependent enzyme B was added to Md, 1 μl methylation-sensitive enzyme A and 1 μl methylation-dependent enzyme B were added to Msd and the total volume was adjusted to 30 μl by the addition of RNase/DNase-free water. The components were mixed gently with pipette and incubated at 37°C for 8-10 h, and the reaction was stopped by heating at 65°C for 20 min. This digested DNA was used as template to detect change in methylation status of the sample after treatment by qPCR. The cp (crossing point) of each digested sample was put into EpiTech Methyl II PCR Array software (SABiosciences Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and the relative fractions of methylated and unmethylated DNA were subsequently determined by comparing the amount in each digest with that of a mock (no enzymes added) digest using a ΔCT method following manufacturer's protocol. The amount of hypermethylated target DNA copies was derived as follows: 2[−Ct(Ms−Mo)−CR]/(1−CR), where CR represents the amount of target DNA copies resistant to enzyme digestion and is defined as 2−Ct(Msd−Mo). The amount of unmethylated DNA was determined as 2[−Ct(Md−Mo)−CR]/(1−CR). All experiments were carried out in duplicates to ensure reproducibility.

Quantification of gene transcript levels by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR): Purified and intact total RNA was converted to cDNA using the RevertAid™ First strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas Life Sciences, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Gene transcript levels of all the genes under study were analyzed by RT-qPCR using absolute quantification method carried out with the Light Cycler 480 (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) as described previously in detail14,15,16.

Statistical analysis: The data were statistically analysed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 for windows (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Normality of quantitative data was checked by measures of Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests of normality17. Differences in the DNA methylation profile and gene transcript expression profile of pre- and post-treatment samples were analyzed using paired Student's t test and Wilcoxon signed rank test (whichever applicable). Correlation of gene promoter methylation to gene transcript levels status was analyzed by Spearman's rank Correlation.

Results

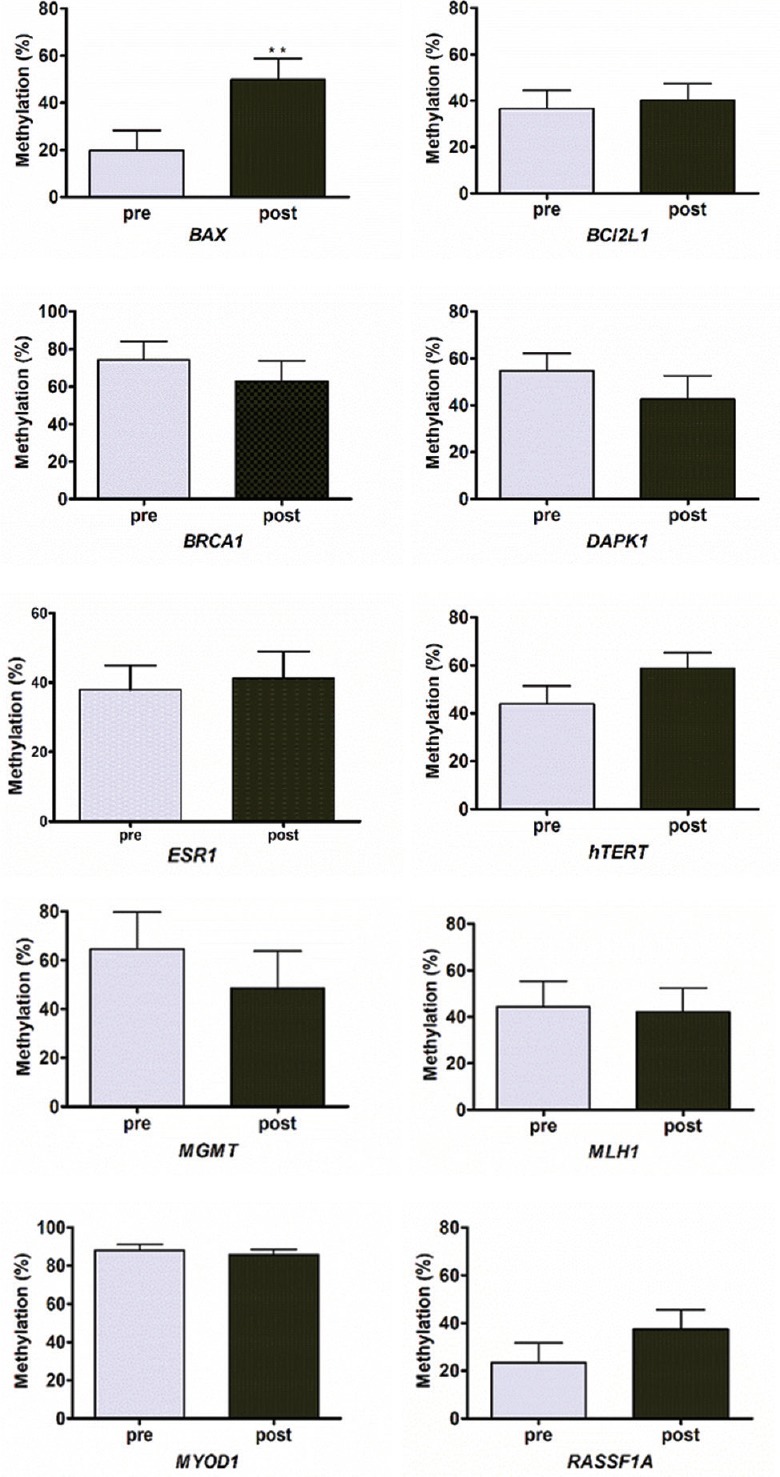

Evaluation of change in gene promoter methylation pattern in response to chemoradiation therapy: The differences in the methylation profile of paired samples following treatment varied from sample to sample. The differences in the mean levels of methylation in the pre-treatment versus post-treatment biopsies are shown in Fig. 1. Overall, the mean percentage methylation of hTERT, RASSF1A and BAX genes was increased and mean percentage methylation of DAPK1, MGMT and BRCA1 genes was decreased in post-treatment samples, whereas the other genes studied did not show any change. Only BAX gene promoter methylation showed a significant increase in response to chemoradiation treatment (P< 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Bar graph showing mean change in gene promoter methylation levels in paired pre- and post-chemoradiation therapy samples of invasive cervical cancer. Values are shown as mean±SD (n=20). **P<0.01 compared to pre value.

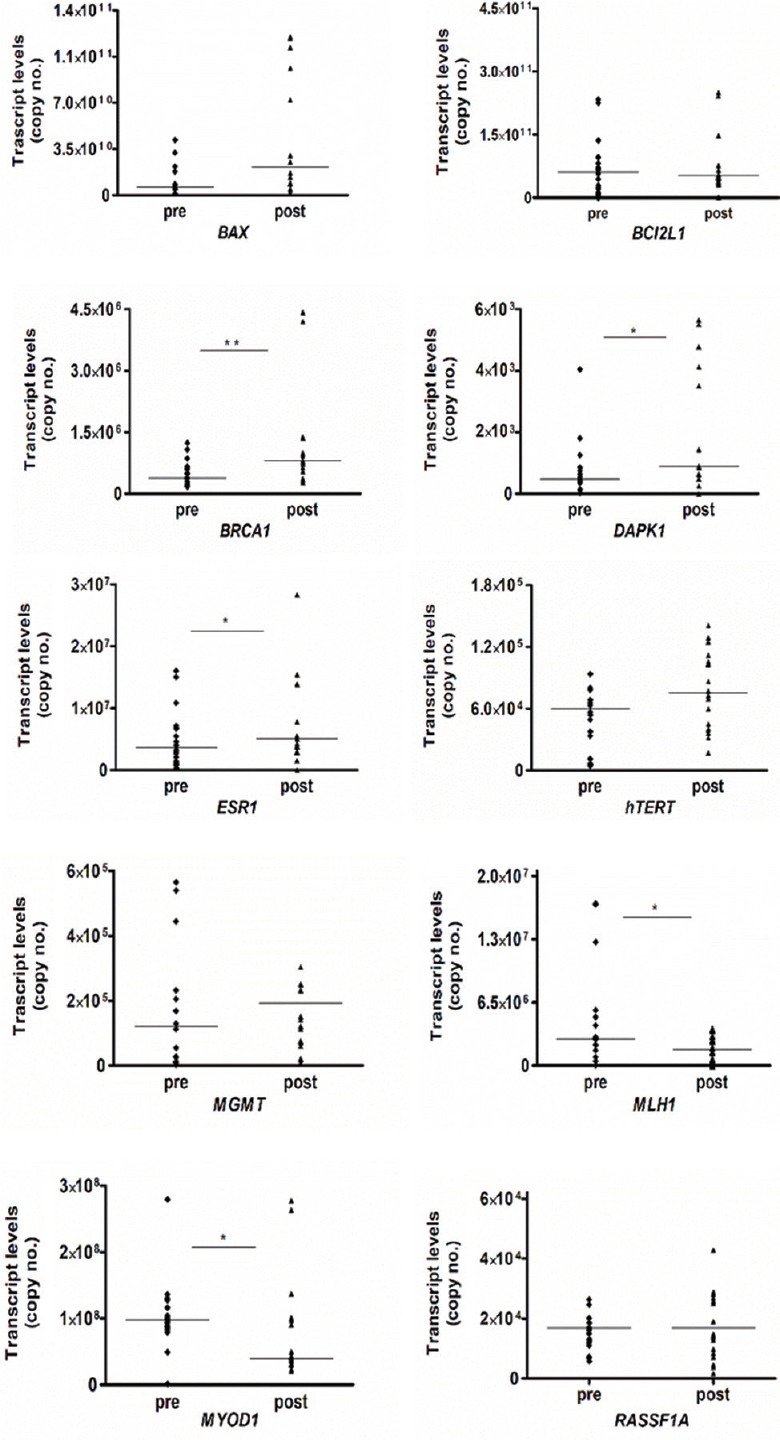

Evaluation of change in gene transcript levels in response to chemoradiation therapy: Absolute quantification was performed to derive copy numbers of transcript levels. The median levels in the pre-treatment versus post-treatment sample were compared and results are shown in Fig. 2. The gene transcript levels of BRCA1 (P<0.01), DAPK1 and ESR1 (P< 0.05) genes were significantly increased, whereas MYOD1 and MLH1 genes were significantly decreased (P< 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Dot plot showing comparison of transcript levels (copy number) in paired pre- and post-chemoradiation therapy samples of invasive cervical cancer. Median values are shown as horizontal bars (n=20). P *<0.05, **<0.01 compared to respective pre values.

Correlation of gene promoter methylation to gene transcript level status: There was a significant correlation of BAX and BCL2L1 gene promoter methylation with corresponding gene transcript expression (Spearman's rho=0.461, P=0.003 and Spearman's rho=0.327, P=0.039, respectively). However, none of the other genes showed a significant correlation with gene expression.

Patient response to chemoradiation therapy: All patients were followed up clinically and all except one responded to the chemoradiation treatment instituted to them and were free of disease at three years follow up. The single case who had LED in this subset of 20 patients showed increase in methylation of DAPK1, MGMT and BRCA1 and increased transcript levels of RASSF1A and MLH1 in addition to increased transcript levels of BRCA1, DAPK1, ESR1 and hTERT following chemoradiation as compared to the remaining 19 cases.

Discussion

The overall survival in invasive cervical cancer is around 50 per cent and the prognosis depends on tumour stage, pelvic lymph node metastasis, tumour volume and vascular invasion in recurrent disease18,19. Patients with invasive cervical cancer are treated primarily by chemoradiation which involves administration of cisplatin along with radiation therapy in the form of intracavitary brachytherapy and external radiation. This is more effective than radiation therapy alone in the treatment of invasive cervical cancer and has improved the overall five-year survival rate from 30 to 50 per cent in Stage II and III patients to about 50 to 70 per cent1,20. It is well recognized that radiation treatment induces cell death by both cellular necrosis and apoptosis; however, cellular biological aspects of response to radiation/chemoradiation therapy are not well understood21. Gene expression profiling studies using microarrays have shown large-scale alterations in genes involved in DNA repair, cell cycle, cell proliferation and apoptosis, angiogenesis and cell-matrix interactions5. A few studies have evaluated molecular alterations following chemoradiation therapy. In one report, biopsy samples from pre- and mid-treatment (chemoradiation) cervical tumours were evaluated using single-color oligo-microarrays, and upregulation of CDKN1A, BAX, TNFSF8 and RRM2B gene transcripts was observed21. In a study by Bae et al22, the effect of IR on colon cancer cells (in vitro) was evaluated after exposure with 2 and 5 Gy irradiation and it was observed that IR induced genome-wide DNA hypomethylation. MGMT promoter methylation has been shown to be associated with improved response to radiation/chemoradiation therapy in glioblastomas23,24,25. In the present pilot study, we evaluated the changes in the gene promoter methylation and gene expression in paired pre- and post-chemoradiation biopsies. The post-treatment biopsy was taken after 10 Gy of fractionated radiotherapy over one week as in previous studies11,15,21. Tissue viability was maintained at this dose of radiation permitting the study of molecular alterations. We have reported previously in an in vitro study that cisplatin affects promoter methylation and the expression pattern of the genes under study and subsequently affects patient's response to therapy7. The present study was an extension of our observation and was carried on patient samples (in vivo) to evaluate changes in the gene promoter methylation and gene expression profile of the patients with invasive cervical cancer treated by chemoradiation therapy. Similar changes were observed in the methylation and gene expression profile post-therapy as observed earlier7; however, it was observed that the changes induced were variable from sample to sample. An overall increase in the methylation of hTERT, RASSF1A and BAX genes was seen, whereas methylation of DAPK1, MGMT and BRCA1 genes was decreased in post-treatment biopsy samples. The fold change was also variable and ranged from 0 to 100 per cent. Only BAX gene methylation showed a significant increase post-chemoradiation. In a previous study on the immunohistochemical expression of Bax, Bcl-2 and Bcl-x1, an increased Bax protein expression was observed in post-RT samples11. It is likely that the expression of the pro-apoptotic Bax is not repressed by methylation. The pro- and anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family are known to have post-transcriptional regulation, especially by microRNAs and other mechanisms such as phosphorylation by kinases which are hyperactive in cancers26.

In contrast to gene promoter methylation, striking changes were observed in the transcript levels of many genes. There was a significant increase in the tissue transcript levels of BRCA1, DAPK and ESR1 and a small but significant decrease in gene transcript levels of MYOD1 and MLH1. The upregulation of BRCA1 transcript may be viewed as a cellular response to DNA damage as it is involved in the repair of damaged DNA. DAPK1 is a pro-apoptotic gene that induces apoptosis by gamma interferon and potentially inhibits metastasis27; therefore, decreased methylation corresponding to increased expression in post-RT samples suggested that the tumour cells were subjected to apoptosis. The implications of the increase in ESR1 transcript and decrease in MYOD1 transcript levels are not clear. ESR1 encodes the oestrogen receptor protein which has no direct role in the cell death mechanism and MYOD1 gene encodes for a protein that regulates myogenic differentiation. Both are related to the levels of cellular differentiation with MYOD1, a marker of cellular dedifferentiation and ESR1 is associated with better differentiated cells of the cervical epithelium13,28.

Decreased transcript levels of MLH1 post-chemotherapy were observed in our study. Previous reports have shown loss of hMLH1 protein expression to be associated with chemotherapy resistance in ovarian and other tumours29; however, existing data on cervical cancer with regard to hMHL1 expression status and methylation are limited. One group has found loss of hMLH1 protein expression in invasive lesions30, whereas others have found the opposite31. Further, presence of microsatellite instability appears to correlate with a worse prognosis32 but not with response to cisplatin in a neoadjuvant setting in cervical cancer33.

It is important to note that all except one patient had no evidence of disease at 36 months’ follow up. Therefore, the clinical implications of our findings need to be ascertained by inclusion of cases which are chemoradiation resistant and compare it to the chemoradiation-sensitive patients. To conclude, chemoradiation therapy appears to induce epigenetic changes in DNA methylation pattern and alterations in gene transcript levels in tissues of invasive cervical cancer which may have implications to understand the biology of tumoral radiation response.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank all the patients who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: This study was supported financially by Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, India (vide grant No. 71/6-Edu-13/1377-1877)

Conflicts of Interest: The first author (SS) is currently working in the Editorial Unit of the Indian Journal of Medical Research as a contractual staff. The remaining three authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Saibishkumar EP, Patel FD, Sharma SC. Results of a phase II trial of concurrent chemoradiation in the treatment of locally advanced carcinoma of uterine cervix: An experience from India. Bull Cancer. 2005;92:E7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mountzios G, Soultati A, Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Dimopoulos MA, Papadimitriou CA, et al. Developments in the systemic treatment of metastatic cervical cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:430–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross GM. Induction of cell death by radiotherapy. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:41–4. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balcer-Kubiczek EK. Apoptosis in radiation therapy: A double-edged sword. Exp Oncol. 2012;34:277–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder AR, Morgan WF. Radiation-induced chromosomal instability and gene expression profiling: Searching for clues to initiation and perpetuation. Mutat Res. 2004;568:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burdak-Rothkamm S, Prise KM. New molecular targets in radiotherapy: DNA damage signalling and repair in targeted and non-targeted cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:151–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.09.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sood S, Srinivasan R. Alterations in gene promoter methylation and transcript expression induced by cisplatin in comparison to 5-Azacytidine in HeLa and SiHa cervical cancer cell lines. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;404:181–91. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2377-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narayan G, Arias-Pulido H, Nandula SV, Basso K, Sugirtharaj DD, Vargas H, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of FANCF: Disruption of Fanconi Anemia-BRCA pathway in cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2994–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang S, Kim JW, Kang GH, Park NH, Song YS, Kang SB, et al. Polymorphism in folate- and methionine-metabolizing enzyme and aberrant CpG island hypermethylation in uterine cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong SM, Kim HS, Rha SH, Sidransky D. Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1982–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adhya AK, Srinivasan R, Patel FD. Radiation therapy induced changes in apoptosis and its major regulatory proteins, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bax, in locally advanced invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:281–7. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000215292.99996.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widschwendter A, Müller HM, Fiegl H, Ivarsson L, Wiedemair A, Müller-Holzner E, et al. DNA methylation in serum and tumors of cervical cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:565–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0825-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhai Y, Bommer GT, Feng Y, Wiese AB, Fearon ER, Cho KR. Loss of estrogen receptor 1 enhances cervical cancer invasion. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:884–95. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sood S, Patel FD, Ghosh S, Arora A, Dhaliwal LK, Srinivasan R, et al. Epigenetic alteration by DNA methylation of ESR1, MYOD1 and hTERT gene promoters is useful for prediction of response in patients of locally advanced invasive cervical carcinoma treated by chemoradiation. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2015;27:720–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokawa K, Shikone T, Otani T, Nakano R. Transient increases of apoptosis and Bax expression occurring during radiotherapy in patients with invasive cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leong DT, Gupta A, Bai HF, Wan G, Yoong LF, Too HP, et al. Absolute quantification of gene expression in biomaterials research using real-time PCR. Biomaterials. 2007;28:203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HY1. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38:52–4. doi: 10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graflund M, Sorbe B, Bryne M, Karlsson M. The prognostic value of a histologic grading system, DNA profile, and MIB-1 expression in early stages of cervical squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:149–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeda N, Sakuragi N, Takeda M, Okamoto K, Kuwabara M, Negishi H, et al. Multivariate analysis of histopathologic prognostic factors for invasive cervical cancer treated with radical hysterectomy and systematic retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:1144–51. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.811208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine EL, Renehan A, Gossiel R, Davidson SE, Roberts SA, Chadwick C, et al. Apoptosis, intrinsic radiosensitivity and prediction of radiotherapy response in cervical carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 1995;37:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(95)01622-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwakawa M, Ohno T, Imadome K, Nakawatari M, Ishikawa K, Sakai M, et al. The radiation-induced cell-death signaling pathway is activated by concurrent use of cisplatin in sequential biopsy specimens from patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:905–11. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.6.4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae JH, Kim JG, Heo K, Yang K, Kim TO, Yi JM. Identification of radiation-induced aberrant hypo methylation in colon cancer. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:56. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, Blatt V, Pession A, Tallini G, et al. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2192–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mock A, Geisenberger C, Orlik C, Warta R, Schwager C, Jungk C, et al. LOC283731 promoter hypermethylation prognosticates survival after radiochemotherapy in IDH1 wild-type glioblastoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:424–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivera AL, Pelloski CE, Gilbert MR, Colman H, De La Cruz C, Sulman EP, et al. MGMT promoter methylation is predictive of response to radiotherapy and prognostic in the absence of adjuvant alkylating chemotherapy for glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:116–21. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yip KW, Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins and cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:6398–406. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YR, Yuan WC, Ho HC, Chen CH, Shih HM, Chen RH. The Cullin 3 substrate adaptor KLHL20 mediates DAPK ubiquitination to control interferon responses. EMBO J. 2010;29:1748–61. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kokabu S, Nakatomi C, Matsubara T, Ono Y, Addison WN, Lowery JW, et al. The transcriptional co-repressor TLE3 regulates myogenic differentiation by repressing the activity of the MyoD transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:12885–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.774570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de las Alas MM, Aebi S, Fink D, Howell SB, Los G. Loss of DNA mismatch repair: Effects on the rate of mutation to drug resistance. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1537–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.20.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciavattini A, Piccioni M, Tranquilli AL, Filosa A, Pieramici T, Goteri G, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system proteins (hMLH1, hMSH2) in cervical preinvasive and invasive lesions. Pathol Res Pract. 2005;201:21–5. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwaśniewska A, Goździcka-Józefiak A, Postawski K, Miturski R. Evaluation of DNA mismatch repair system in cervical dysplasias and invasive carcinomas related to HPV infection. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2002;23:231–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung TK, Cheung TH, Wang VW, Yu MY, Wong YF. Microsatellite instability, expression of hMSH2 and hMLH1 and HPV infection in cervical cancer and their clinico-pathological association. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2001;52:98–103. doi: 10.1159/000052951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ercoli A, Ferrandina G, Genuardi M, Zannoni GF, Cicchillitti L, Raspaglio G, et al. Microsatellite instability is not related to response to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:308–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.15221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]