Abstract

The efficacy of antidepressants to treat major depressive disorder (MDD) varies by patient characteristics. This post-hoc analysis evaluated the effects of vilazodone across patient subgroups in adults with MDD. Data were pooled from four trials of vilazodone (NCT00285376, NCT00683592, NCT01473394, and NCT01473381). Mean change from baseline to week 8 in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score, MADRS response (≥50% total score improvement), and MADRS remission (total score≤10) were analyzed in the pooled intent-to-treat population (vilazodone=1254, placebo=964) and in subgroups of patients categorized by sex, age, MDD duration, recurrent episodes, baseline MADRS total score, and current episode duration. MADRS total score improvement was significantly greater with vilazodone versus placebo in the intent-to-treat population and in all patient subgroups (P<0.001). MADRS response and remission rates significantly separated from placebo (P<0.05) regardless of age, sex, MDD duration, recurrent MDD, and baseline symptom severity [except remission in patients with very severe baseline symptoms (MADRS score≥35)] and in patients with a shorter current episode duration (≤12 months). Despite the limitations associated with analyzing uncommon outcomes (e.g. MADRS remission) in small subgroups, vilazodone was an effective treatment in multiple patient populations, including those where reduced efficacy has previously been reported: males, older individuals, patients with a longer duration of MDD, and patients with recurrent depression.

Keywords: antidepressant, demographics, major depressive disorder, symptom severity, vilazodone

Introduction

According to the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (Kessler et al., 2012), the lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) is 16.6%. Patients with MDD differ across a wide range of features, including age, sex, symptom severity, disease duration, episode quantity and duration, and disease recurrence. Differences in patient demographics and disease characteristics have been shown to impact treatment outcomes. For example, decreased treatment response has been linked to various demographic subgroups, including older age (Tedeschini et al., 2011; Reed et al., 2012) and male sex (Khan et al., 2005; Trivedi et al., 2006). In addition, baseline disease characteristics such as chronic depression (Rush et al., 2004), more severe depression at baseline (Howland et al., 2008; Ansseau et al., 2009), longer duration of illness (Okuda et al., 2010; Rush et al., 2012), and the presence of a higher number of previous MDD episodes (Ansseau et al., 2009) are also associated with worse treatment response.

The aim of antidepressant treatment is remission, defined as the absence of depressive symptoms; despite the availability of numerous pharmaceutical treatments, no single therapy is effective in every patient. It is estimated that during a 1-year period, only 6% of patients with MDD will achieve remission with treatment (Pence et al., 2012). Remission is correlated with improved patient function; therefore, it is not surprising that a low rate of remission is associated with impaired work, social, and family-life functioning (Ansseau et al., 2009). As efficacy has been shown to vary by patient characteristics, evaluating the effectiveness of antidepressants in patient subgroups may provide information that can better inform clinicians about treatment options to help individual patients achieve remission and improve the overall quality of life.

Vilazodone is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist that is approved in the USA and Canada for the treatment of MDD in adults. In four short-term clinical trials with vilazodone 20–40 mg/day (Rickels et al., 2009; Khan et al., 2011; Croft et al., 2014; Mathews et al., 2015), vilazodone was effective versus placebo in improving depressive symptoms, as measured by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (primary efficacy parameter) (Montgomery and Asberg, 1979). To evaluate the efficacy of vilazodone in patients characterized by demographics, MDD history, and symptom severity, data were pooled from the short-term clinical trials of vilazodone.

Materials and methods

Clinical studies

Data were pooled from four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials; detailed methods have been previously described (Rickels et al., 2009; Khan et al., 2011; Croft et al., 2014; Mathews et al., 2015). In three studies (NCT00285376, NCT00683592, NCT01473394), patients were randomized (1 : 1) to 8 weeks of double-blind treatment with placebo or vilazodone 40 mg/day (Rickels et al., 2009; Khan et al., 2011; Croft et al., 2014). In one study (NCT01473381), patients were randomized (1 : 1 : 1) to 10 weeks of double-blind treatment with placebo, vilazodone 20 mg/day or vilazodone 40 mg/day; a citalopram arm was also included as an active control for assay sensitivity (Mathews et al., 2015). The primary endpoint of each study was the mean change from baseline to the end of double-blind treatment (week 8 or week 10) in MADRS total score. All studies were carried out in accordance with good clinical practice guidelines (US Food and Drug Administration, International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, and/or Declaration of Helsinki) and with the approval of the Institutional Review Board at each study site. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study participants

Adult patients, 18 years or older, who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (APA, 2000) criteria for MDD were eligible to participate in the constituent studies. Key clinical inclusion criteria included a current major depressive episode of at least 4 weeks and less than 2 years (Rickels et al., 2009; Khan et al., 2011) or at least 8 weeks to 12 months or less (Croft et al., 2014; Mathews et al., 2015), 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960) total score of at least 22 and item one (depressed mood) score of at least 2 (Rickels et al., 2009; Khan et al., 2011), and MADRS total score of at least 26 (Croft et al., 2014; Mathews et al., 2015). Key exclusion criteria included a DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorder other than MDD, history of bipolar or psychotic disorders, nonresponse to at least two previous antidepressants of different classes after adequate treatment duration at recommended doses, and suicide risk, based on investigator judgment, previous suicide attempt within the past year, Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale score (Posner et al., 2011), and/or MADRS item 10 (suicidal thoughts) score of at least 5.

Post-hoc analyses

Analyses were carried out in the pooled intent-to-treat population, defined as all patients who received at least one dose of double-blind study treatment and had a baseline and at least one postbaseline MADRS total score assessment. Efficacy was evaluated in patient subgroups categorized by demographic characteristics, including sex (male, female) and age; age cutoffs (<45, 45 to <60, and ≥60 years) were based on National Comorbidity Survey Replication data (Kessler et al., 2003). Efficacy was also evaluated by MDD history, including duration of illness (<2, 2 to <10, and ≥10 years), recurrent episodes (yes, no), and current episode duration (≤6, >6 to ≤12, and >12 months), and symptom severity using baseline MADRS total score (<30, ≥30, and ≥35).

The least squares (LS) mean change from baseline to week 8 in MADRS total score was analyzed in the pooled population and within each subgroup population. LS mean differences (LSMDs) between treatment groups were analyzed using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures with study, treatment group, visit, subgroup, treatment-by-subgroup, subgroup-by-visit, treatment group-by-visit, and subgroup-by-treatment-by-visit as fixed effects, and baseline value and baseline value-by-visit as covariates using a compound symmetry covariance matrix; effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d calculation. MADRS response was defined as greater than or equal to 50% total score improvement from baseline to end of treatment, and MADRS remission was defined as a total score of less than or equal to 10 at the end of treatment. End of treatment was defined as the last available postbaseline assessment during the double-blind treatment period. MADRS response and remission were analyzed using a logistic regression with treatment group and baseline MADRS total scores as explanatory variables and MADRS response or remission as the dependent variable; odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P values were calculated. Numbers needed to treat (NNTs) were calculated from the response or remission rate differences between vilazodone and placebo.

Results

Patients

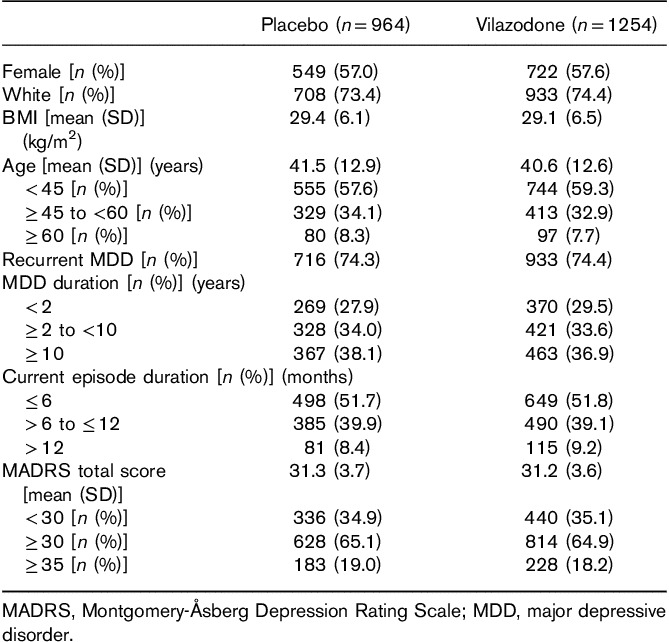

The pooled intent-to-treat population included 2218 patients (placebo, n=964; vilazodone, n=1254). Demographic and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients were female, White, and under 45 years of age. Almost half of the patient population had current episode duration of more than 6 months, and nearly 75% of all patients had experienced recurrent MDD. Approximately 65% of patients entered the study with a MADRS score of at least 30, indicating a severe level of depressive symptoms (Nemeroff, 2007).

Table 1.

Patient demographic and baseline characteristics (pooled intent-to-treat population)

Efficacy

MADRS total score

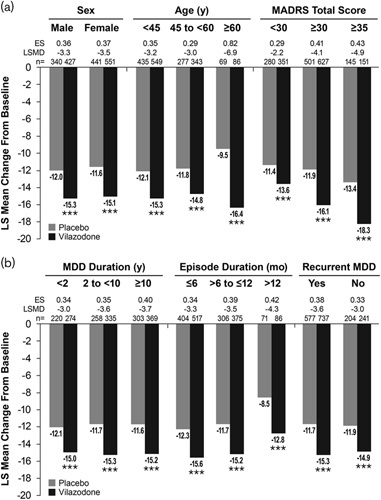

In the pooled population, LS mean change from baseline to week 8 in MADRS total score was significantly greater for vilazodone relative to placebo [LSMD (95% CI): −3.4 (−4.1 to −2.7); P<0.001; d=0.37]. When patients were categorized by demographic subgroup (sex, age) and baseline symptom severity, the LS mean change from baseline in MADRS total score was significantly greater for vilazodone compared with placebo in all subgroups (Fig. 1a). Similarly, when categorized by MDD history (MDD duration, episode duration, and recurrent MDD), the difference in MADRS total score was statistically significant in favor of patients treated with vilazodone compared with placebo for all subgroups (Fig. 1b). LSMDs for vilazodone versus placebo were comparable in males and females (−3.3 and −3.5, respectively) and regardless of MDD duration (−3.0 to −3.7), episode duration (−3.3 to −4.3), or the presence or absence of recurrent depression (−3.6 and −3.0, respectively). The LSMD for vilazodone versus placebo in patients 60 years of age or older (−6.9) was greater than in patients younger than 60 years of age (−3.0 to −3.2), and differences from placebo in patients with a baseline MADRS score of at least 30 or at least 35 (−4.1 and −4.9, respectively) were greater than in patients with a MADRS score less than 30 (−2.2).

Fig. 1.

MADRS total score change from baseline in patient subgroups. Differences for vilazodone versus placebo in MADRS total score change from baseline were significant in each patient subgroup tested. (a) Catagorized by demographics and baseline symptom severity. (b) Categorized by MDD history. ***P<0.001 versus placebo. ES, effect size (Cohen’s d); LS, least squares; LSMD, least squares mean difference; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; mo, months; n, number of patients with an available MADRS total score at week 8; y, years.

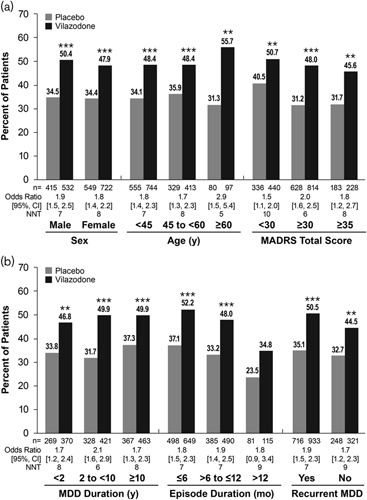

MADRS response

In the overall pooled population, a significantly higher percentage of vilazodone-treated patients compared with placebo-treated patients achieved MADRS response [49.0 vs. 34.4%; OR (95% CI): 1.8 (1.5–2.2); P<0.001; NNT=7]. When stratified by sex, age, and symptom severity, the percentage of patients meeting criteria for MADRS response was significantly higher for vilazodone than for placebo in every patient subgroup (Fig. 2a). When stratified by MDD history, significantly higher rates of response were also observed for vilazodone versus placebo regardless of MDD duration and recurrence status (Fig. 2b). Significantly higher response rates in favor of vilazodone versus placebo were seen in subgroups with an episode duration of 6 months or less, and more than 6 to 12 months or less; response rates in the subgroup of patients with a current episode duration of more than 12 months were numerically higher for vilazodone-treated patients versus placebo-treated patients (34.8 vs. 23.5%), but the difference did not reach statistical significance. The NNT was less than or equal to 10 for all patient subgroups (see Fig. 2 for individual subgroup NNT).

Fig. 2.

MADRS response in patient subgroups. Differences for vilazodone versus placebo in MADRS response were significant in each patient subgroup tested, with the exception of patients with an episode duration >12 months. (a) Catagorized by demographics and baseline symptom severity. (b) Categorized by MDD history. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus placebo. CI, confidence interval; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; mo, months; n, number of patients with an available postbaseline MADRS total score; NNT, number needed to treat; y, years.

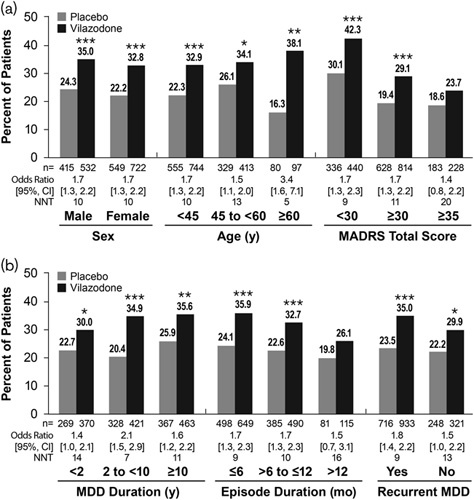

MADRS remission

The percentage of patients in the overall pooled population meeting criteria for MADRS remission was significantly higher in the vilazodone group than in the placebo group [33.7 vs. 23.1%; OR (95% CI): 1.7 (1.4–2.1); P<0.001; NNT=10]. Remission rates were significantly higher for vilazodone compared with placebo in both male and female patients and in all age groups (Fig. 3a). Among patients stratified by symptom severity, a significantly higher percentage of vilazodone-treated patients with a baseline MADRS score less than 30 and greater than or equal to 30 met remission criteria compared with placebo. The percentage of vilazodone-treated patients with a baseline MADRS total score of 35 or greater who met remission criteria was not statistically significant versus placebo.

Fig. 3.

MADRS remission in patient subgroups. Differences for vilazodone versus placebo in MADRS remission were significant in each patient subgroup tested, with the exception of patients with an episode duration >12 months or MADRS total score ≥35. (a) Catagorized by demographics and baseline symptom severity. (b) Categorized by MDD history. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus placebo. CI, confidence interval; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; mo, months; n, number of patients with an available postbaseline MADRS total score; NNT, number needed to treat; y, years.

In patients categorized by MDD duration and recurrent MDD, and in patients with a current episode duration of 6 months or less and more than 6 to 12 months or less, rates of remission were also significantly higher for vilazodone-treated versus placebo-treated patients (Fig. 3b). Similar to MADRS response, the MADRS remission rate was not significantly different for vilazodone and placebo in the subgroup of patients with an episode duration of more than 12 months; however, the percentage of patients that met remission criteria was numerically higher in vilazodone-treated patients than in placebo-treated patients.

Discussion

In this post-hoc analysis of four randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials in patients with MDD, vilazodone 20–40 mg/day was an effective treatment across subgroups of patients categorized by demographics, symptom severity, and MDD history. In parallel with each individual short-term trial, a statistically significant difference in favor of vilazodone versus placebo in change from baseline in MADRS total score was seen in the overall pooled population (P<0.0001). In addition, statistically significant improvement for vilazodone compared with placebo was observed in subgroups of patients characterized by sex, age, baseline MADRS total score, MDD duration, episode duration, and recurrent MDD (all groups, P<0.001). In this post-hoc analysis, the LSMD for vilazodone versus placebo in MADRS total score was −3.4 in the pooled population and ranged from −2.2 to −6.9 in the subgroup populations; as an LSMD of more than two points on the MADRS is considered to be clinically meaningful (Montgomery and Moller, 2009), the difference between treatments was clinically important as well as statistically significant in all subgroups. These results expand upon a previous preliminary assessment of vilazodone efficacy in patient subgroups from two of the four clinical trials included in this analysis (Reed et al., 2012).

The percentage of vilazodone-treated patients reaching response (≥50% reduction in MADRS total score) and remission (MADRS total score ≤10) was also statistically greater in the pooled population and across the majority of patient subgroups. An NNT of 10 or less was found for treatment response in each patient subgroup and in a little more than half (nine of 16) of the subgroups for treatment remission. A between-group difference of at least 10%, which corresponds with an NNT of 10 or less, is generally associated with a clinically meaningful outcome for antidepressant treatment (Montgomery and Moller, 2009; Citrome and Ketter, 2013). Though statistical testing was not conducted between subgroups within each category, no consistent trends between subgroups were observed with vilazodone treatment.

Inconsistent treatment effects have previously been reported in clinical trials of antidepressants in specific patient subgroups. For example, reduced efficacy has been reported in males (Khan et al., 2005; Trivedi et al., 2006), older individuals (Tedeschini et al., 2011), patients with a longer duration of MDD (Okuda et al., 2010; Rush et al., 2012), and patients with a higher number of previous depressive episodes (Ansseau et al., 2009). As such, it is of note that vilazodone demonstrated broad efficacy across baseline demographic and disease categories in these post-hoc analyses. When patients were stratified by demographics, a significant treatment effect was observed in both male and female patients and in all age groups, including older adults (≥60 years of age). In addition, in the subgroup of patients 60 years or older, there was a low NNT (5) for MADRS response and remission and a larger effect size on each efficacy parameter relative to the other age groups. This large effect size may be partially explained by either the low placebo effect (a smaller mean change from baseline compared with active treatment) or by the proportionally smaller sample size of patients who were between 60 and 70 years of age.

The majority of patients with MDD experience chronic or recurrent depression (Eaton et al., 2008; APA, 2010; Rush et al., 2012). Clinical data indicate that antidepressants are not as effective in these patient populations. For example, lower rates of remission have been observed in patients with a higher number of previous episodes (Ansseau et al., 2009), a longer duration of illness (Okuda et al., 2010), and chronic MDD (Rush et al., 2012). The results of the current analysis showed that vilazodone treatment significantly improved MDD symptoms regardless of MDD duration or length of the current depressive episode, and in patients with or without recurrent MDD. In contrast to other antidepressant studies (Ansseau et al., 2009; Okuda et al., 2010), response and remission rates were significantly higher for vilazodone than for placebo regardless of MDD duration and recurrent MDD, with the exception of patients with an episode duration of more than 12 months. In these patients, the effect size for symptom improvement was numerically greater than in other episode duration subgroups; however, the difference in MADRS response and remission rates for vilazodone and placebo was not significant.

Chronic MDD is associated with a reduced placebo effect and a lower likelihood to respond to antidepressant treatment (Papakostas and Fava, 2009; Rush et al., 2012; Kornstein et al., 2016). As patients in the longer than 12-months subgroup had episode duration between 1 and 2 years, and chronic MDD is defined as an index episode of at least 2 years, the diagnostic entities associated with chronic MDD may encompass these patients. The placebo effect for symptom improvement in the longer than 12-months subgroup was smaller than that in subgroups with shorter episode duration, which may have contributed to the slightly larger effect size of vilazodone in this subgroup. Although the difference between vilazodone and placebo in the percentage of patients meeting criteria for response was not statistically significant in patients with episode duration longer than 12 months, the OR was similar to that of the other subgroups, and the NNT of 9 suggests that the lack of significance may have been due to the smaller sample size in this subgroup. This was not the case for the remission outcome, where the rates for vilazodone and placebo were more similar (26.1 vs. 19.8%, respectively; NNT=16). These results suggest that patients with more chronic depression symptoms receive meaningful benefit from vilazodone treatment, though achievement of full remission may be less common than in patients with less chronic symptoms.

The efficacy of antidepressant drugs can vary by baseline depression symptom severity (Kasper et al., 1997; Hirschfeld, 1999; Nemeroff, 2007). For instance, studies have demonstrated an increase in symptom severity is associated with a decreased rate of remission (Howland et al., 2008; Ansseau et al., 2009). Remission, defined by rating scale criteria, is more difficult to achieve in patients with severe depression (baseline MADRS score >28) (Nemeroff, 2007) as patients with a higher baseline MADRS score must make greater improvements to reach a predefined remission score (e.g. MADRS score ≤10) than patients with a lower baseline MADRS score. Results from the current post-hoc analysis showed rates of remission with vilazodone were not statistically different than placebo in patients with very severe baseline depression (MADRS score ≥35). However, improvement in depressive symptoms, as measured by change from baseline in MADRS total score, significantly favored vilazodone treatment over placebo in this subgroup and showed a similar effect size to patients with lower baseline symptom severity; rates of response were also significant, with similar odds ratios observed in all baseline severity subgroups.

Limitations of this study include those inherent in post-hoc analyses; P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of the individual studies may limit generalizability as they do not incorporate all patients with depression typically seen in real-world practice. As patients over the age of 70 years were excluded from the constituent studies, the subgroup of patients 60 years or older only included patients between 60 and 70 years of age; the small sample size in this subgroup may have limited the ability to detect significant between-group differences. In addition, MADRS remission is typically low in individual short-term studies and analyses may be underpowered when patients are divided into smaller subgroups, even in a pooled analysis. Finally, short-term study duration (8 or 10 weeks) does not provide any information on the long-term effects of vilazodone in the subgroup populations.

Conclusion

Results from this post-hoc analysis of four large clinical trials showed that, relative to placebo, vilazodone significantly reduced symptoms of depression in subgroups of patients categorized by demographic characteristics, disease history, and symptom severity. A clinically meaningful treatment effect was found in all of the subgroups included in this post-hoc analysis. Despite the difficulty in evaluating uncommon outcomes (e.g. MADRS remission) in small subgroups, this study demonstrated vilazodone was an effective treatment in populations of patients where less robust efficacy has been previously observed in other antidepressants studies, including males, older individuals, patients with a longer duration of MDD, and patients with recurrent depression. Vilazodone may be an effective treatment option for heterogenous populations of adults with MDD regardless of sex, age, baseline symptom severity, or MDD history.

Acknowledgements

This analysis was funded by Forest Research Institute, Inc., an Allergan affiliate, Jersey City, New Jersey, USA.

Writing and editorial support were provided by Jill Shults, PhD, and Carol Brown, MS, at Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Conflicts of interest

S. Kornstein has received research support from Forest Laboratories (an Allergan affiliate), Pfizer Inc., Takeda, and Palatin Technologies; has served as consultant/advisory board member to Allergan, Forest Laboratories, Eli Lilly and Company, Palatin Technologies, Pfizer Inc., Shire, Sunovion, and Takeda; and has received royalties from Guilford Press. C. Gommoll and J. Edwards are full-time employees of Allergan. C.T. Chang was an employee at Allergan at the time the study was carried out.

References

- Ansseau M, Demyttenaere K, Heyrman J, Migeotte A, Leyman S, Mignon A. (2009). Objective: remission of depression in primary care The Oreon Study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 19:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text revision Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- APA (2010). Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, third edition Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L, Ketter TA. (2013). When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract 67:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft HA, Pomara N, Gommoll C, Chen D, Nunez R, Mathews M. (2014). Efficacy and safety of vilazodone in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 75:e1291–e1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Shao H, Nestadt G, Lee HB, Bienvenu OJ, Zandi P. (2008). Population-based study of first onset and chronicity in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65:513–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RM. (1999). Efficacy of SSRIs and newer antidepressants in severe depression: comparison with TCAs. J Clin Psychiatry 60:326–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland RH, Wilson MG, Kornstein SG, Clayton AH, Trivedi MH, Wohlreich MM, et al. (2008). Factors predicting reduced antidepressant response: experience with the SNRI duloxetine in patients with major depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry 20:209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper S, Zivkov M, Roes KC, Pols AG. (1997). Pharmacological treatment of severely depressed patients: a meta-analysis comparing efficacy of mirtazapine and amitriptyline. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 7:115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU. (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 21:169–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Brodhead AE, Schwartz KA, Kolts RL, Brown WA. (2005). Sex differences in antidepressant response in recent antidepressant clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol 25:318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Cutler AJ, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, Athanasiou M, Robinson DS, et al. (2011). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week study of vilazodone, a serotonergic agent for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 72:441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornstein SG, Gommoll C, Chen C, Kramer K. (2016). The effects of levomilnacipran ER in adult patients with first-episode, highly recurrent, or chronic MDD. J Affect Disord 193:137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews M, Gommoll C, Chen D, Nunez R, Khan A. (2015). Efficacy and safety of vilazodone 20 and 40 mg in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 30:67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 134:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Moller HJ. (2009). Is the significant superiority of escitalopram compared with other antidepressants clinically relevant? Int Clin Psychopharmacol 24:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff CB. (2007). The burden of severe depression: a review of diagnostic challenges and treatment alternatives. J Psychiatr Res 41:189–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda A, Suzuki T, Kishi T, Yamanouchi Y, Umeda K, Haitoh H, et al. (2010). Duration of untreated illness and antidepressant fluvoxamine response in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 64:268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI, Fava M. (2009). Does the probability of receiving placebo influence clinical trial outcome? A meta-regression of double-blind, randomized clinical trials in MDD. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 19:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, O’Donnell JK, Gaynes BN. (2012). The depression treatment cascade in primary care: a public health perspective. Curr Psychiatry Rep 14:328–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. (2011). The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 168:1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CR, Kajdasz DK, Whalen H, Athanasiou MC, Gallipoli S, Thase ME. (2012). The efficacy profile of vilazodone, a novel antidepressant for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin 28:27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Athanasiou M, Robinson DS, Gibertini M, Whalen H, Reed CR. (2009). Evidence for efficacy and tolerability of vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 70:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi M, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Ibrahim H, et al. (2004). One-year clinical outcomes of depressed public sector outpatients: a benchmark for subsequent studies. Biol Psychiatry 56:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Zisook S, Fava M, Sung SC, Haley CL, et al. (2012). Is prior course of illness relevant to acute or longer-term outcomes in depressed out-patients? A STAR*D report. Psychol Med 42:1131–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschini E, Levkovitz Y, Iovieno N, Ameral VE, Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. (2011). Efficacy of antidepressants for late-life depression: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry 72:1660–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, et al. (2006). Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 163:28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]