Immunotherapy targeting the programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1)–programmed cell death ligand-1 (PDL-1) axis in sepsis is poised for clinical trials, although optimal inclusion criteria and predictors of response are not well characterized.

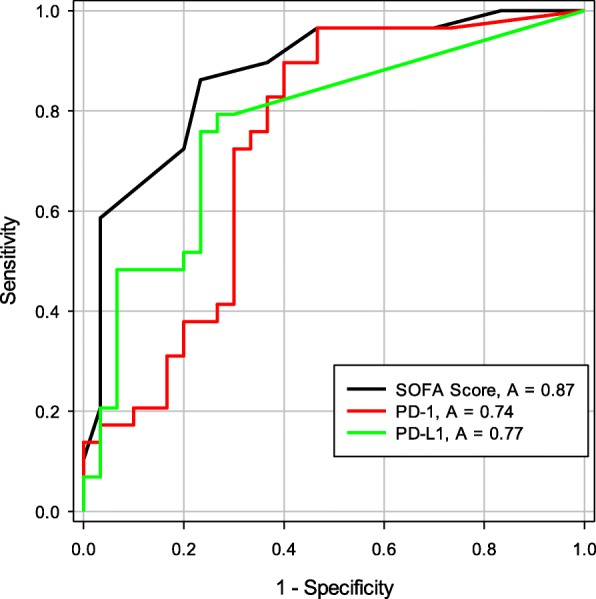

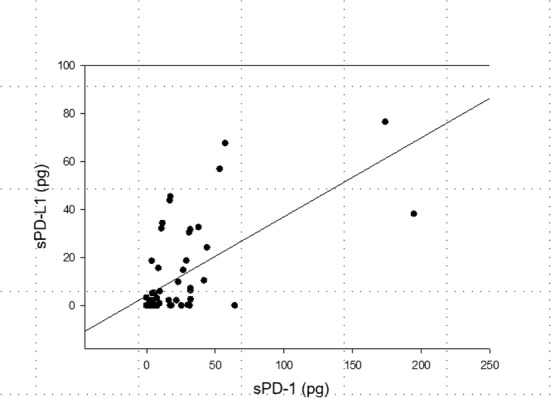

We evaluated the kinetics of soluble (s)PD-1 and sPD-L1 in 30 septic intensive care unit (ICU) patients and 30 nonseptic ICU patients (Table 1). sPD-1 and sPD-L1 were significantly elevated among the septic cohort compared with the nonseptic ICU patients at enrollment (17.7 pg/ml vs. 4.5 pg/ml, p = 0.002; and 29.9 pg/ml vs. 11.3 pg/ml, p = 0.02; respectively) and were associated with sepsis (Fig. 1). Higher sPD-L1 on day 3 was associated with mortality among septic patients (16.7 pg/ml vs. 3.0 pg/ml, p = 0.054) and also in the total ICU cohort (14.9 pg/ml vs. 2.7 pg/ml, p = 0.026). Soluble PD-L1 regressed on interleukin (IL)-6 and interferon (IFN)γ levels were significantly associated in the total ICU cohort and septic patients, possibly pointing to upstream triggers for post-transcriptional modifications. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α regressed on sPD-1 and sPD-L1 was significant in all populations including septic survivors, revealing possible downstream effects of sPD-1 and sPD-L1. Initial sPD-1 levels correlated with a drop in lymphocyte count to < 1 × 109/L (area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve 0.72, p = 0.006) and to < 0.6 × 109/L (area under the ROC curve 0.68, p = 0.02). sPD-L1 also correlated with lymphocyte count drop to < 1 × 109/L during the hospital stay. The correlation between the two immune checkpoint molecules, sPD-1 and sPD-L1, was also significant on enrollment, and at days 1 and 3 (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.004, respectively; Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variables | Septic patients (n = 30) | Control subjects (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 63.3 (49.3–74.1) | 58.6 (52.8–64.6) |

| Male, n (%) | 11 (36) | 19 (63) |

| White, n (%) | 23 (76) | 25 (83) |

| Past medical history | ||

| COPD/asthma/fibrosis, n (%) | 11 (36) | 2 (7) |

| CAD/MI, CHF, AF, n (%) | 16 (53) | 7 (23) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 5 (17) | 10 (33) |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 8 (27) | 6 (20) |

| CKD/ESRD, n (%) | 5 (17) | 1 (3) |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (13) |

| Connective tissue disease, n (%) | 3 (10) | 0 |

| Arthritis, n (%) | 3 (10) | 3 (10) |

| Clinical assessment | ||

| WBC (×10−9/L), median (IQR) | 12.8 (6.9–19.1) | 9.1 (7.6–10.9) |

| SOFA score, median (IQR) | 7 (5–9) | 2 (1–4) |

| Shock, n (%) | 24 (80) | 2 (6) |

| Site of infection in septic patients (n) | ||

| Pneumonia | 13 | |

| Genitourinary tract infection | 11 | |

| Abdominal infection | 2 | |

| Meningitis | 1 | |

| Multiple sites of infection | 1 | |

| Bacteremia | 9 | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Organism of infection if known in septic patients (n) | ||

| Escherichia coli not extended-spectrum β-lactamase producer | 4 | |

| Escherichia coli extended-spectrum β-lactamase producer | 2 | |

| Enterobacter | 1 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 1 | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 | |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | |

| Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | |

| Candida albicans | 1 | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1 | |

| Bacillus species not anthracis | 2 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 | |

AF atrial fibrillation, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CAD coronary artery disease, CHF congestive heart Failure, CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, IQR interquartile range, MI myocardial infarction, SOFA sequential organ function assessment, WBC white blood cell

Fig. 1.

The area under the ROC curve for the discrimination of sepsis by soluble programmed death protein-1 (sPD-1) and soluble programmed death ligand-1 (sPD-L1). These are the day 0 area under the ROC curves for Sequential Organ Function Assessment (SOFA) score, sPD-1 (pg/ml), and sPD-L1 (pg/ml) for the discrimination of patients who have sepsis. Soluble PD-L1 outperforms sPD-1 for discrimination of sepsis

Fig. 2.

Correlation between soluble programmed death protein-1 (sPD-1) and soluble programmed death ligand-1 (sPD-L1) on day 0 among all ICU patients. The Pearson correlation between sPD-L1 (pg/ml on y axis) and sPD-1 (pg/ml on x axis) is 0.629 at the time of enrollment

sPD-1 and sPD-L1 are easily sampled, making them advantageous biomarkers in sepsis. A recent study demonstrated elevated sPD-1 among patients with infected pancreatitis [1]. sPD-1 may serve as an indicator of severity of sepsis among emergency room patients [2]. Lange et al. [3] reported that sPD-1 levels did not differ significantly between septic and nonseptic critically ill patients and had no association with outcome among septic patients. Our results may stem from sampling a different population to Lange and colleagues. Our controls, while critically ill, had lower severity of illness and mortality. Additionally, we excluded patients with immunocompromise, malignancy, and organ transplantation due to possible iatrogenic skewing of sPD-1 and sPD-L1. Approximately half of the control group in Lange et al. developed infections; thus, observations comparing sepsis versus nonseptic groups were limited to initial measurement only.

sPD-1 and sPD-L1 are point-of-care tests that might eventually guide personalized medicine in sepsis. These soluble immune checkpoints can risk-stratify patients for immunotherapy in sepsis and may potentially serve as targets themselves.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants in this study.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GR5223260.1001). GSP received funding to support statistical analyses for this project from Rhode Island Hospital.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IFN

Interferon

- IL

Interleukin

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein-1

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death ligand-1

- ROC

Receiver operator characteristic

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

Authors’ contributions

MML and SO constructed the biorepository for this study. DB contributed to the IRB for this study and handling of specimens. TW enrolled patients and collected biosamples and AP supervised biobank maintenance. RZ performed the multiplex analysis. GSP performed the statistical analysis for this project, GSP and SM created the figures presented. DB drafted and edited the manuscript, while SM, SO, GSP, and MML edited and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Rhode Island Hospital IRB 4159-14. All participants consented prior to enrollment.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Debasree Banerjee, Phone: (401) 444-4191, Email: banerjed19@gmail.com.

Sean Monaghan, Email: sean_monaghan@brown.edu.

Runping Zhao, Email: runping_zhao@lifespan.org.

Thomas Walsh, Email: Thomas.walsh@lifespan.org.

Amy Palmisciano, Email: apalmisciano@lifespan.org.

Gary S. Phillips, Email: gphillips.stat@gmail.com

Steven Opal, Email: steven_opal@brown.edu.

Mitchell M. Levy, Email: Mitchell_levy@brown.edu

References

- 1.Chen Y, Li M, Liu J, Pan T, Zhou T, Liu Z, Tan R, Wang X, Tian L, Chen E, et al. sPD-L1 expression is associated with immunosuppression and infectious complications in patients with acute pancreatitis. Scand J Immunol. 2017;86(2):100–106. doi: 10.1111/sji.12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao Y, Jia Y, Li C, Fang Y, Shao R. The risk stratification and prognostic evaluation of soluble programmed death-1 on patients with sepsis in emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;36(1):43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lange A, Sunden-Cullberg J, Magnuson A, Hultgren O. Soluble B and T lymphocyte attenuator correlates to disease severity in sepsis and high levels are associated with an increased risk of mortality. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.