Abstract

Objective

To describe the prevalence, use of antidepressants, and predictors of major and minor depression among non-pregnant women of childbearing age.

Methods

Using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2007–2014, we performed a cross-sectional study of 3,705 non-pregnant women of childbearing age. The primary outcome is the prevalence of major depression, and secondary outcomes are the prevalence of minor depression, rates of antidepressant use, and predictors of major and minor depression. Major and minor depression were classified using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9. Univariate and multivariate associations between major depression and minor depression with potential predictors were estimated using multinomial logistic regression.

Results

The overall prevalences of major and minor depression were 4.8% (95% confidence intervals (CI) = 4.0%–5.7%) and 4.3% (95% CI = 3.5%–5.2%), respectively. The prevalences of antidepressant use among women with major depression and minor depression were 32.4% (95% CI = 25.3%–40.4%) and 20.0% (95% CI = 12.9%–29.7%), respectively. Factors most strongly associated with major depression were government insurance (adjusted relative risk ratio (aRR) =2.49; 95% CI = 1.56–3.96) and hypertension (aRR = 2.09; 95% CI = 1.25–3.50); for minor depression, these were education less than high school (aRR = 4.34; 95% CI = 2.09–9.01) or high school education (aRR = 2.92; 95% CI = 1.35–6.31).

Conclusions

Our analysis indicates that 1 in 20 non-pregnant women of childbearing age experience major depression. Antidepressants are used by one third of those with major depression and one fifth of those with minor depression.

INTRODUCTION

Major depression during pregnancy affects up to 12.7% of pregnant women1 and is associated with severe maternal and perinatal morbidity, including: maternal self-harm or suicide2, impaired fetal growth, preterm delivery or low birthweight infants3, impaired maternal functioning4, inadequate mother-child bonding5, and adverse effects on later childhood development6, 7. To address these issues, the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care have published recommendations to improve the screening and management of women with perinatal mood disorders, including depression.8 Furthermore, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends depression screening for pregnant and postpartum women.9

Given that 54% of women with depression before pregnancy suffer with depression during pregnancy10, 11 and that 50% of US pregnancies are unplanned12, better diagnosis and treatment of non-pregnant women with depression may reduce the burden of perinatal mental illness. Epidemiological studies are needed to plan management strategies for women with major depression before pregnancy. However, few studies have examined the prevalence of major depression among women of childbearing age.10, 13, 14 Furthermore, postpartum women were not clearly differentiated from non-pregnant women remote from pregnancy in these studies. Therefore, our primary aim was to describe the prevalence of major depression among non-pregnant women of childbearing age using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Secondary aims were to describe the prevalence of minor depression, examine rates of antidepressant use among women with major and minor depression, and perform an exploratory analysis to identify potential predictors for major and minor depression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey to assess the health and nutritional status of a representative sample of non-institutionalized U.S. civilians, selected using a complex, multistage probability design. Data are collected continuously and released in two-year cycles.15 We received a waiver from the Stanford University IRB because the analysis relied on publicly available data without participant identifiers.

We combined data from the 2007–2014 data collection cycles. Because pregnancy status was not available for women aged less than 20 years and more than 44 years, these women were excluded. To limit the likelihood of misclassifying women with perinatal or postpartum depression,1, 11, 16 we excluded pregnant women and postpartum women (up to 12 months after delivery). Pregnancy status was self-reported or determined with a urine pregnancy test.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) was administered as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to detect major and minor depression. We used the PHQ-9 scores to identify women with major and minor depression. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item depression questionnaire17 used to assess depressive symptomatology. It is a well-established screening instrument to identify patients at risk for depression in a number of clinical settings, with good evidence of reliability and validity.17 For each question, participants select a response based on a Likert-type scale, with responses including: not at all (0); several days (1); more than half the days (2); and nearly every day (3). The PHQ-9 diagnosis of major depression is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV)18 criteria and requires that subjects have five or more of the nine depressive symptoms for at least “more than half the days” in the past 2 weeks, with at least one of the symptoms being depressed mood or anhedonia. One symptom “thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way” counts if present at all. Potential risk factors for major depression were abstracted from the dataset. These included: age; race; marital status; education; monthly income to poverty ratio (categorized as low, medium, or high based on tertiles of their distribution), body mass index (BMI); health insurance; physical activity; alcohol use over last year; smoking history; and a prior history of asthma, hypertension or diabetes.

The PHQ-9 diagnosis of minor depression were based on DSM-IV criteria,18 which was classified by the presence of two, three, or four depressive symptoms for at least “more than half the days” in the past 2 weeks, with one of the symptoms being depressed mood or anhedonia.

Use of antidepressant medication was ascertained from the Prescription Medication questionnaire. The questionnaire inquired about the intake of prescribed medication in the past 30 days. The complete list of antidepressants is presented in Table 1. Patients were classified as taking antidepressants if any of the medications were taken at least once in the past month.

Table 1.

Estimated prevalence of antidepressant use among childbearing age women

| Drug Class | Major depression

(n=207) Proportion (95% CI) |

Minor depression

(n=192) Proportion (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Any antidepressant | 32.4 (25.3–40.4) | 20.0 (12.9–29.7) |

| SSRIs: citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline | 21.3 (15.0–29.3) | 9.5 (5.1–17.2) |

| SNRIs : desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran, venlafaxine, and levomilnacipran | 7.2 (4.1–12.4) | 3.3 (1.2–9.1) |

| Miscellaneous: agomelatine, vilazodone, and bupropion | 4.7 (2.3–9.5) | 4.9 (2.2–10.5) |

| Phenylpiperazines: trazodone and nefazodone | 8.4 (4.6–15.0) | 1.1 (0.3–4.4) |

| Tricyclic antidepressants: amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, imipramine, nortriptyline, serotonin, doxepin, trimipramine and protriptyline | 3.7 (1.5–8.9) | 2.3 (0.7–7.6) |

| Tetracyclic antidepressants: mirtazapine, amoxapine, and maprotiline | 3.0 (1.0–8.5) | 0.5 (0.1–3.6) |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors : phenelzine, selegiline, isocarboxazid, tranylcypromine and unspecified monoamine oxidase inhibitors | 0 | 0 |

Data presented as percent (95% confidence intervals)

SNRIs = serotonin—norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA (Version 14.0, College Station, TX), accounting for the complex survey design. Sample weights are provided by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to permit calculations of nationally representative estimates and population weights.15 Means and standard errors were calculated for continuous variables and proportions were calculated for categorical variables. Statistical differences between continuous variables were tested with an adjusted Wald test for survey data, analogous to the parametric t test. Statistical differences between categorical variables were tested with chi-square tests.

The prevalences of major and minor depression, and antidepressant use by type of depression were calculated. Univariate and multivariate associations between major depression and minor depression with potential risk factors were estimated using multinomial logistic regression. The results are presented as relative risk ratios with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). We identified variables independently associated with major and minor depression where the P-value was less than 0.05. To account for multiple comparisons, a false discovery rate criteria of <5% was applied.

RESULTS

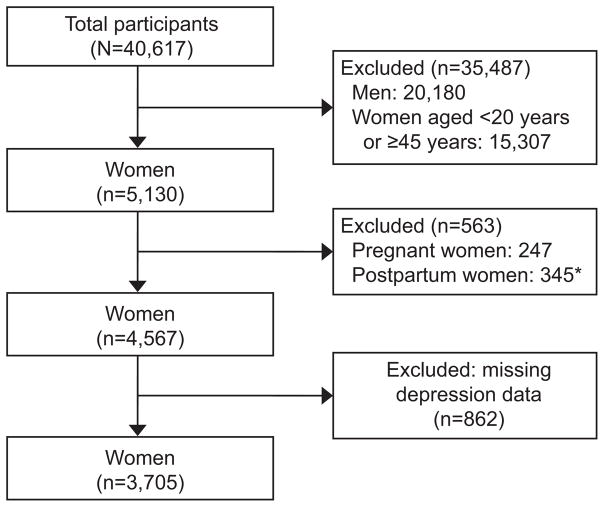

A cohort flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. Between 2007 and 2014, we identified 4,567 non-pregnant childbearing age women. After excluding 862 women with missing PHQ-9 data, our final study cohort comprised 3,705 women. Characteristics of women with reported PHQ-9 scores vs. those missing PHQ-9 scores are presented in Table 2. Compared to those missing data, women reporting PHQ-9 scores were more likely to be Non-Hispanic White, college educated or higher, have a high income to poverty ratio, BMI>18.5, report alcohol consumption, have a smoking history, asthma, be insured, do moderate exercise, and report good general health status. The overall prevalences of major and minor depression were 4.8% (95% CI = 4.0%–5.7%) and 4.3% (95% CI = 3.5%–5.2%), respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow chart. *Women who also self-reported as pregnant (n=29).

Table 2.

Comparisons of Demographic and Medical Characteristics among Childbearing Age Women with PHQ-9 Data and Those Excluded Because of Missing PHQ-9 Data.

| Characteristic | Women reporting PHQ-9 Data (n=3705) | Women with Missing PHQ-9 Data (n=862) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr): | .529 | ||

| 20–34 | 56.6 (53.9–59.2) | 53.6 (48.5–58.6) | |

| 35–39 | 20.3 (18.8–22.0) | 22.1 (19.1–25.3) | |

| 40–44 | 23.1 (21.0–25.4) | 24.4 (19.8–29.6) | |

| Race: | <.001 | ||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 61.8 (57.5–65.8) | 51.2 (45.1–57.3) | |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 13.2 (11.2–15.7) | 16.1 (13.5–19.0) | |

| Mexican-American | 10.4 (8.4–12.9) | 11.8 (8.8–15.7) | |

| Other | 14.6 (12.9–16.5) | 20.9 (16.7–25.8) | |

| Education: | <.001 | ||

| Less than high school | 13.9 (12.3–15.7) | 20.4 (17.2–24.2) | |

| High school | 18.0 (16.1–20.1) | 18.9 (15.5–22.8) | |

| Some college or AA degree | 37.9 (35.6–40.3) | 31.9 (27.4–36.7) | |

| College graduate and above | 30.1 (27.4–33.1) | 28.4 (24.1–33.2) | |

| Marital status: | .12 | ||

| Never married | 31.1 (28.1–34.2) | 26.1 (21.8–30.8) | |

| Married or live with partners | 57.2 (54.1–60.2) | 61.5 (56.8–66.0) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 11.7 (10.5–13.1) | 12.4 (9.8–15.6) | |

| Ratio of family income to poverty: | <.001 | ||

| Low | 22.5 (20.2–25.0) | 31.0 (27.7–34.6) | |

| Middle | 28.9 (26.7–31.2) | 25.8 (21.7–30.5) | |

| High | 43.3 (40.1–46.5) | 32.0 (27.8–36.4) | |

| Missing | 5.3 (4.3–6.6) | 11.2 (8.4–14.7) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): | <.001 | ||

| <18.5 | 2.5 (2.0–3.2) | 5.0 (3.3–7.4) | |

| 18.5–24.99 | 37.0 (34.6–39.5) | 36.3 (32.1–40.8) | |

| 25–29.99 | 25.7 (23.8–27.6) | 24.7 (20.9–28.9) | |

| >=30 | 34.5 (32.7–36.3) | 30.5 (26.9–34.3) | |

| Missing | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 3.5 (2.0–6.3) | |

| Alcohol consumption: | <.001 | ||

| Never | 20.7 (18.6–22.9) | 1.5 (0.6–3.6) | |

| Less than 1 drink/day | 24.5 (22.8–26.4) | 0 | |

| More than 1 drink/day | 54.7 (52.6–56.8) | 0 | |

| Missing | 0.1 (0–0.2) | 98.5 (96.4–99.4) | |

| Smoking | .11 | ||

| Current smoker | 22.6 (20.7–24.6) | 21.0 (17.0–25.6) | |

| Former smoker | 13.3 (11.8–14.8) | 10.5 (7.8–14.1) | |

| Never smoker | 64.2 (61.6–66.7) | 68.4 (62.8–73.5) | |

| Asthma | 10.8 (9.7–11.9) | 7.0 (5.3–9.1) | .002 |

| Hypertension | 13.6 (12.5–14.9) | 10.1 (7.7–13.3) | .060 |

| Diabetes | 4.1 (3.5–5.0) | 3.0 (2.1–4.5) | .35 |

| Insurance type: | .017 | ||

| No insurance | 24.7 (22.8–26.8) | 28.4 (24.1–33.1) | |

| Private insurance | 56.6 (53.7–59.5) | 49.5 (44.9–54.0) | |

| Government/state/military insurance | 18.3 (16.4–20.5) | 22.2 (18.3–26.6) | |

| Missing | 0.3 (0.2–0.7) | 0 | |

| Seen mental health professional | 11.1 (9.8–12.6) | 11.7 (8.8–15.4) | .73 |

| Moderate to rigorous physical activity | 74.9 (73.0–76.7) | 66.7 (62.4–70.8) | <.001 |

| General health: | <.001 | ||

| Excellent | 11.0 (9.7–12.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | |

| Very good | 34.7 (32.6–36.9) | 0.3 (0–2.5) | |

| Good | 39.8 (38.0–41.6) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | |

| Fair | 12.6 (11.4–13.9) | 0.6 (0.1–3.1) | |

| Poor | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | 0 | |

| Missing | 0 | 98.4 (96.4–99.3) |

The prevalence of any antidepressant use among women with major depression and minor depression was 32.4% (95% CI: 25.3%–40.4%) and 20.0% (95% CI: 12.9%–29.7%), respectively (Table 1). Among women with major depression, the most commonly used antidepressants were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (21.3%), phenylpiperazines (8.4%) and serotonin—norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (7.2%). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were the most common antidepressant used among women with minor depression (9.5%). No women were taking trimipramine, amoxapine, maprotiline, isocarboxazid, or tranylcypromine.

Table 3 shows the demographic and medical characteristics among childbearing age women with major depression, minor depression, and no depression. Table 4 shows the associations between correlates with major and minor depression in the multinomial models. In the multivariable analysis, being a current smoker, having hypertension, and government insurance were independently associated with major depression. In contrast, factors independently associated with minor depression were: Black race, other race, all education categories below college graduate level, current smoker, and asthma. Factors most strongly associated with major depression were government insurance (aRR = 2.49; 95% CI = 1.56–3.96) and hypertension (aRR = 2.09; 95% CI = 1.25–3.5), whereas for minor depression, these were: education less than high school (aRR = 4.34; 95% CI = 2.09–9.01) and high school education (aRR = 2.92; 95% CI = 1.35–6.31). To account for possible overfitting in our models, we performed sensitivity analyses using backward selection for variable inclusion in each multivariable model (Table 5). Risk factors identified in these sensitivity analyses were consistent with those identified in our full models.

Table 3.

Demographic and medical characteristics of childbearing age women by depression status

| Characteristic | Major depression (n=207) | Minor depression (n=192) | No depression (n=3306) | P value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | ||

| Age (yr): | <.001 | ||||||

| 20–34 | 92 | 46.7 (38.1–55.5) | 103 | 57.8 (49.8–65.4) | 1866 | 57.0 (54.0–59.9) | |

| 35–39 | 57 | 25.3 (18.9–33.1) | 44 | 22.9 (16.1–31.4) | 668 | 20.0 (18.2–21.8) | |

| 40–44 | 58 | 28.0 (20.0–37.6) | 45 | 19.3 (14.5–25.3) | 772 | 23.0 (20.8–25.5) | |

| Race: | <.001 | ||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 92 | 58.2 (49.1–66.8) | 60 | 44.1 (34.3–54.5) | 1358 | 62.8 (58.5–66.8) | |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 57 | 20.4 (14.8–27.5) | 51 | 20.8 (15.1–28.0) | 655 | 12.5 (10.5–14.9) | |

| Mexican-American | 24 | 7.7 (4.6–12.7) | 28 | 10.9 (6.9–17.0) | 566 | 10.5 (8.4–13.2) | |

| Other | 34 | 13.7 (9.2–19.8) | 53 | 24.1 (17.2–32.8) | 727 | 14.2 (12.5–16.1) | |

| Education: | <.001 | ||||||

| Less than high school | 71 | 27.2 (21.4–33.9) | 61 | 27.4 (20.6–35.4) | 574 | 12.6 (11.1–14.4) | |

| High school | 46 | 20.6 (14.8–28.0) | 45 | 24.2 (16.2–34.5) | 614 | 17.6 (15.6–19.6) | |

| Some college or AA degree | 71 | 40.0 (31.5–49.1) | 66 | 38.3 (30.1–47.2) | 1217 | 37.8 (35.3–40.4) | |

| College graduate and above | 19 | 12.2 (7.3–19.6) | 20 | 10.2 (6.0–16.7) | 900 | 32.0 (29.1–35.1) | |

| Marital status: | <.001 | ||||||

| Never married | 63 | 29.2 (22.3–37.2) | 68 | 35.3 (27.7–43.6) | 1097 | 31.0 (27.9–34.3) | |

| Married or live with partners | 88 | 45.0 (37.5–52.7) | 98 | 50.5 (41.8–59.1) | 1819 | 58.2 (54.9–61.3) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 56 | 25.8 (19.7–33.1) | 26 | 14.3 (10.1–19.8) | 389 | 10.9 (9.5–12.3) | |

| Ratio of family income to poverty: | <.001 | ||||||

| Low | 105 | 40.0 (32.7–47.9) | 76 | 36.2 (29.3–43.8) | 931 | 21.0 (18.6–23.5) | |

| Middle | 61 | 34.4 (27.3–42.2) | 65 | 34.6 (27.1–42.9) | 990 | 28.3 (26.2–30.6) | |

| High | 29 | 21.4 (15.2–29.4) | 37 | 22.6(16.1–30.6) | 1166 | 45.4 (42.1–48.8) | |

| Missing | 12 | 4.1 (2.0–8.3) | 14 | 6.6 (3.3–12.8) | 219 | 5.3 (4.2–6.7) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): | <.001 | ||||||

| <18.5 | 5 | 3.9 (1.3–11.0) | 3 | 1.7 (0.4–6.5) | 79 | 2.4 (1.9–3.2) | |

| 18.5–24.99 | 41 | 17.9 (12.8–24.5) | 68 | 35.8 (29.0–43.2) | 1173 | 38.1 (35.5–40.8) | |

| 25–29.99 | 44 | 23.7 (17.0–32.0) | 43 | 22.8 (16.9–30.1) | 852 | 25.9 (24.0–27.9) | |

| >=30 | 115 | 53.9 (46.1–61.6) | 77 | 39.1 (31.4–47.4) | 1186 | 33.3 (31.4–35.2) | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.6 (0.2–2.4) | 1 | 0.57 (0–4.1) | 16 | 0.31 (0.2–0.5) | |

| Alcohol consumption: | <.001 | ||||||

| Never | 55 | 25.8 (19.0–34.1) | 58 | 24.6 (18.2–32.3) | 796 | 20.2 (18.1–22.5) | |

| Less than 1 drink/day | 32 | 16.2 (10.2–24.7) | 35 | 17.8 (12.9–24.0) | 814 | 25.3 (23.4–27.2) | |

| More than 1 drink/day | 119 | 57.3 (49.7–64.6) | 98 | 57.4 (48.8–65.6) | 1692 | 54.5 (52.3–56.7) | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.7 (0–4.9) | 1 | 0.3 (0–1.9) | 4 | 0 (0–0.1) | |

| Smoking | <.001 | ||||||

| Current smoker | 106 | 47.7 (39.8–55.7) | 69 | 40.1 (32.1–48.8) | 673 | 20.4 (18.6–22.4) | |

| Former smoker | 19 | 9.3 (5.3–15.8) | 8 | 4.7 (2.3–9.3) | 376 | 13.9 (12.3–15.5) | |

| Never smoker | 82 | 43.0 (35.3–51.0) | 115 | 55.2 (46.7–63.5) | 2257 | 65.7 (62.9–68.4) | |

| Asthma | 48 | 23.0 (17.5–29.6) | 31 | 19.7 (14.0–27.1) | 317 | 9.7 (8.6–10.9) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 74 | 33.5 (25.5–42.5) | 43 | 21.8 (14.8–30.9) | 424 | 12.2 (11.1–13.5) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 25 | 10.5 (7.0–15.4) | 14 | 6.0 (3.4–10.4) | 137 | 3.7 (3.0–4.6) | <.001 |

| Insurance type: | <.001 | ||||||

| No insurance | 63 | 30.5 (24.3–37.5) | 73 | 33.8 (27.1–41.2) | 980 | 24.0 (22.0–26.1) | |

| Private insurance | 388 | 28.9 (21.6–37.4) | 67 | 40.4 (31.8–49.6) | 1687 | 58.8 (56.0–61.6) | |

| Government/state/military insurance | 208 | 39.5 (32.5–47.0) | 51 | 25.2(18.8–32.8) | 630 | 16.9 (15.0–19.0) | |

| Missing | 2 | 1.2 (0.3–5.1) | 1 | 0.7 (0–4.8) | 9 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | |

| Seen mental health professional in last 12 months | 71 | 35.2 (27.8–43.3) | 42 | 25.1 (18.4–33.2) | 272 | 9.2 (7.9–10.6) | <.001 |

| Moderate to rigorous physical activity | 120 | 61.0 (52.1–69.2) | 104 | 53.5 (45.5–61.3) | 2380 | 76.6 (74.6–78.5) | <.001 |

| General health: | <.001 | ||||||

| Excellent | 2 | 0.6 (0.2–2.5) | 7 | 3.2 (1.5–6.6) | 360 | 11.9 (10.5–13.4) | |

| Very good | 18 | 9.6 (5.7–15.9) | 38 | 23.6 (17.6–30.9) | 1022 | 36.5 (34.2–38.9) | |

| Good | 72 | 42.8 (35.8–50.0) | 79 | 40.5 (32.6–48.8) | 1402 | 39.6 (37.6–41.7) | |

| Fair | 81 | 31.5 (24.9–38.9) | 54 | 26.9 (19.8–35.4) | 472 | 10.9 (9.8–12.2) | |

| Poor | 34 | 15.5 (11.2–21.2) | 14 | 5.9 (3.5–9.7) | 50 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |

P-values are from Chi-square tests.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Relative Risk Ratios for the Risk of Major Depression vs. Non-depression and Minor Depression vs. Non-depression by Characteristics of Reproductive Aged Women*

| Characteristic | Major depression vs Non depression | Minor depression vs Non depression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude RRR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | P value‡ | Crude RRR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | P value‡ | |

| Age (yr): | ||||||||

| 20–34 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 35–39 | 1.55 (0.99–2.42) | .054 | 1.45 (0.86–2.45) | .17 | 1.13 (0.70–1.82) | .61 | 1.12 (0.68–.84) | .64 |

| 40–44 | 1.48 (0.92–2.40) | .11 | 1.24 (0.70–2.18) | .45 | 0.83 (0.56–1.21) | .33 | 0.87 (0.56–1.35) | .53 |

| Race: | ||||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 1.75 (1.12–2.75) | .015 | 1.16 (0.67–2.01) | .59 | 2.36 (1.54–3.63) | <.001 | 2.05 (1.22–3.45) | .008 |

| Mexican-American | 0.79 (0.47–1.34) | .38 | 0.64 (0.33–1.25) | .19 | 1.47 (0.79–2.76) | .23 | .91 (.51–1.61) | .74 |

| Other | 1.04 (0.63–1.70) | .88 | 0.87 (0.50–1.53) | .63 | 2.42 (1.52–3.84) | <.001 | 2.35 (1.42–3.91) | .001 |

| Education: | ||||||||

| College graduate and above | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Less than high school | 5.68 (3.09–10.46) | <.001 | 1.83 (0.88–3.80) | .10 | 6.84 (3.80–12.30) | <001 | 4.34 (2.09–9.01) | <.001 |

| High school | 3.09 (1.59–6.02) | .001 | 1.25 (0.60–2.62) | .54 | 4.34 (2.15–8.77) | <.001 | 2.92 (1.35–6.31) | .007 |

| Some college or AA degree | 2.78 (1.50–5.17) | .002 | 1.40 (0.67–2.90) | .36 | 3.19 (1.66–6.15) | .001 | 2.59 (1.35–4.97) | .005 |

| Marital status: | ||||||||

| Never married | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Married or live with partners | 0.82 (0.56–1.21) | .31 | 0.92 (0.60–1.42) | .72 | .76 (0.51–1.13) | .18 | 0.96 (0.62–1.49) | .87 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 2.53 (1.57–4.05) | <.001 | 1.60 (0.93–2.75) | .091 | 1.16 (0.74–1.81) | .52 | 1.15 (0.65–2.01) | .63 |

| Ratio of family income to poverty | ||||||||

| Low | 4.05 (2.54–6.44) | <.001 | 1.50 (0.86–2.63) | 3.48 (2.25–5.39) | <.001 | 1.53 (0.84–2.79) | ||

| Middle | 2.57 (1.59–4.15) | <.001 | 1.51 (0.86–2.64) | .15 | 2.46 (1.54–3.91) | <.001 | 1.55 (0.92–2.59) | .16 |

| High | Reference | Reference | .15 | Reference | Reference | .096 | ||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2): | ||||||||

| <18.5 | 3.41 (1.01–11.56) | .049 | 3.33 (0.90–12.37) | 0.74 (0.18–3.06) | .67 | 0.64 (0.17–2.43) | ||

| 18.5–24.99 | Reference | Reference | .07 | Reference | Reference | .50 | ||

| 25–29.99 | 1.94 (1.15–3.29) | .014 | 1.58 (0.87–2.85) | .13 | 0.94 (0.62–1.42) | .76 | 0.72 (0.48–1.08) | .11 |

| >=30 | 3.45 (2.24–5.32) | <.001 | 1.93 (1.11–3.35) | 0.02 | 1.25 (0.85–1.85) | .26 | 0.74 (0.49–1.14) | .17 |

| Alcohol consumption: | ||||||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Less than 1 drink/day | 0.50 (0.27–0.94) | .033 | 0.71 (0.35–1.43) | .33 | 0.58 (0.36–0.94) | .026 | 0.87 (0.53–1.41) | .56 |

| More than 1 drink/day | 0.82 (0.56–1.21) | .32 | 0.93 (0.59–1.47) | .76 | 0.87 (0.57–1.32) | .50 | 1.10 (0.73–1.67) | .65 |

| Cigarette Smoking: | ||||||||

| Never smoker | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Former smoker | 1.03 (0.53–1.96) | .93 | 0.86 (0.43–1.74) | .67 | 0.40 (0.19–0.84) | .017 | 0.45 (0.21–0.97) | .043 |

| Current smoker | 3.56 (2.58–4.92) | <.001 | 2.02 (1.31–3.12) | .002 | 2.34 (1.61–3.39) | <.001 | 1.66 (1.14–2.42) | .009 |

| Asthma | 2.79 (1.90–4.09) | <.001 | 1.79 (1.13–2.82) | .013 | 2.29 (1.48–3.53) | <.001 | 2.11 (1.31–3.41) | .003 |

| Hypertension | 3.61 (2.39–5.45) | <.001 | 2.09 (1.25–3.50) | .005 | 2.01 (1.24–3.26) | .005 | 1.69 (0.97–2.97) | .065 |

| Diabetes | 3.04 (1.83–5.04) | <.001 | 1.40 (0.69–2.83) | .34 | 1.65 (0.87–3.13) | .12 | 0.97 (0.43–2.15) | .93 |

| Insurance type: | ||||||||

| Private insurance | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No insurance | 2.59 (1.71–3.93) | <.001 | 1.84 (1.14–2.95) | .013 | 2.05 (1.39–3.03) | .001 | 1.11 (0.68–1.81) | .68 |

| Government/state/military insurance | 4.76 (3.21–7.07) | <.001 | 2.49 (1.56–3.96) | <.001 | 2.17 (1.39–3.37) | .001 | 1.13 (0.68–1.87) | .63 |

Multinomial logistic regression were used. Multivariate model adjusted for age, race, marital status, education, monthly income to poverty ratio, body mass index, health insurance, physical activity, alcohol use, smoking, a prior history of asthma, hypertension and diabetes. Statistically significant associations were denoted by bold text.

CI = Confidence Intervals; RR = relative risk ratio.

Multiplicity adjustment using Benjamini-Hochberg method with a false discovery rate of 5% was used to decide statistical significance.

Table 5.

Adjusted Relative Risk Ratios for the Risk of Major Depression vs. Non-depression and Minor Depression vs. Non-depression by Characteristics of Reproductive Aged Women using backward selection*

| Major depression vs Non depression Adjusted RR (95% CI) | P value | Minor depression vs Non depression Adjusted RR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race: | ||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 1.29 (0.77–2.13) | .33 | 1.80 (1.09–2.96) | .021 |

| Mexican-American | 0.65 (0.33–1.26) | .20 | 1.04 (.59–1.82) | .89 |

| Other | 0.97 (0.57–1.67) | .92 | 2.37 (1.47–3.82) | .001 |

| Education: | ||||

| College graduate and above | Reference | Reference | ||

| Less than high school | 2.59 (1.37–4.92) | .004 | 4.38 (2.31–8.30) | <.001 |

| High school | 1.59 (0.82–3.05) | .16 | 3.11 (1.54–6.30) | .002 |

| Some college or AA degree | 1.71 (0.89–3.30) | .11 | 2.52 (1.31–4.86) | .006 |

| Marital status: | ||||

| Never married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Married or live with partners | 0.94 (0.61–1.43) | .77 | 0.90 (0.58–1.38) | .62 |

| widowed/divorced/separated | 2.00 (1.19–3.36) | .001 | 1.05 (0.64–1.72) | .86 |

| Cigarette Smoking: | ||||

| Never smoker | Reference | Reference | ||

| Former smoker | 0.91 (0.47–1.79) | .79 | 0.44 (0.20–0.92) | .031 |

| Current smoker | 2.08 (1.39–3.12) | .001 | 1.70 (1.13–2.56) | .012 |

| Asthma | 1.89 (1.24–2.87) | .004 | 1.98 (1.23–3.18) | .005 |

| Hypertension | 2.60 (1.69–3.99) | <.001 | 1.56 (0.93–2.63) | .094 |

| Insurance type: | ||||

| Private insurance | Reference | Reference | ||

| No insurance | 2.04 (1.32–3.16) | .002 | 1.32 (0.86–2.03) | .21 |

| Government/state/military insurance | 2.99 (1.96–4.56) | <.001 | 1.27 (0.79–2.05) | .32 |

Data are adjusted relative risk ratios (95%CI) unless otherwise specified.

CI = Confidence Intervals; RR = Relative Risk

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that 1 in 20 non-pregnant women of childbearing age experience major depression, with approximately 1 in 3 women with major depression reporting antidepressant use. Given these findings and the limited guidance for managing severely depressed women prior to pregnancy,16 there is unmet need for stakeholders in obstetrics, primary care, and psychiatry to coordinate approaches to optimize care and prepregnancy counseling for women with major depression.

Our prevalence estimate for major depression falls within the range reported for depression during pregnancy (3.1% to 4.9%).1 In contrast, in two national surveys, the prevalence of a major depressive episode among non-pregnant women of childbearing age ranged from 11.1% to 12.2%.13, 14 However, neither survey differentiated postpartum women from non-pregnant women remote from pregnancy, therefore these estimates may be inflated. We observed similar prevalences for minor and major depression (4.3% vs. 4.8%, respectively). This has public health relevance as high rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders have been reported among adolescents with subclinical depression.19, 20 Of additional concern, up to 27% of adults with minor depression develop more severe forms, including major depression or dysthymia.21 Longitudinal studies are needed to examine perinatal outcomes among women with minor depression.

Rates of antidepressant use varied according to depression severity, with a higher rate among women with major depression (32.4%) compared to those with minor depression (20%). In contrast to our findings, Ko et al. reported that 47% of women with a past year history of major depression received treatment with prescription medication.13 Rate discrepancies may be explained by the different time windows for assessing antidepressant use and different definitions for depression. Despite these rate discrepancies, findings from these national studies are consistent with other population-wide studies that report undertreatment of major depression in the general population.22, 23 For women with minor depression, the efficacy of antidepressant use is unclear24 which may explain the lower utilization rate in this group.

In our multivariable analysis, several modifiable states — hypertension and smoking — were independently associated with major depression. Links between hypertension and smoking with depression have been reported in other studies.25–28 Although we cannot ascertain causation, the prevalence of each comorbid state among women with major depression was high (hypertension=33.5%, smoking=47.7%). Compared to women with private insurance, women with public insurance had a 2.5-fold increased risk of major depression. Prior research indicated that patients with mental health problems are more likely to be uninsured compared to those without these problems.29 Our data showed a similar trend but these associations were not statistically significant.

Our study has several limitations. The cross-sectional nature of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data limited our ability to assess the effect of treatment on recently diagnosed women, or to estimate the rate of a partial response to treatment. It is unclear whether antidepressants were exclusively prescribed for depression treatment. Medications in the classes under study can be used for anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, binge eating, mood stabilization for bipolar disorders, insomnia, different pain conditions, and urinary incontinence.30 Furthermore, non-pharmacological treatments for depression, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, were not described in the dataset. Because National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys only provides information on pregnancy history for women aged 20–44 years, we could not account for women aged <20 years or >44 years in our analysis. Our examination of predictors for major and minor depression was exploratory and the reported associations may be altered in the presence of unmeasured confounders. The statistically significant associations may also represent chance findings, especially as multiple comparisons were performed. We could not account for parity or number of prior live births in our analysis because of a high rate of missing data for each variable in our study cohort (44% and 50%, respectively). Lastly, 862 women had missing PHQ- 9 data, and these women differed from our study population along variables that were important for determining depression risk, therefore our findings are potentially prone to selection bias.

Our results provide a cross-sectional estimate of the prevalence of major and minor depression affecting non-pregnant women of childbearing age in the United States. These data also suggest that a substantial proportion of women with severe depression are untreated or undertreated. Further studies are needed to determine if improved screening and treatment of severe depression in non-pregnant women of childbearing age can secondarily reduce the prevalence of perinatal and postpartum depression.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure and acknowledgements: Supported by funding from the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative, and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Butwick is a recipient of an award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1K23HD070972).

The authors thank Dr. Elena Kuklina and Dr. Jean Ko, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who reviewed the manuscript for content and accuracy.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G. Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening, accuracy, and screening outcomes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. Evidence report/technology asssessment No.119 from RTI -University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ) under Contract no.290-02-0016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oates M. Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:279–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012–24. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLearn KT, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM, Marks E, Hou W. Maternal depressive symptoms at 2 to 4 months post partum and early parenting practices. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:279–84. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Righetti-Veltema M, Conne-Perreard E, Bousquet A, Manzano J. Postpartum depression and mother-infant relationship at 3 months old. J Affect Disord. 2002;70:291–306. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fihrer I, McMahon CA, Taylor AJ. The impact of postnatal and concurrent maternal depression on child behaviour during the early school years. J Affect Disord. 2009;119:116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay DF, Pawlby S, Angold A, Harold GT, Sharp D. Pathways to violence in the children of mothers who were depressed postpartum. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:1083–94. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendig S, Keats JP, Hoffman MC, Kay LB, Miller ES, Moore Simas TA, et al. Consensus Bundle on Maternal Mental Health: Perinatal Depression and Anxiety. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:422–30. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, et al. Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;315:380–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, Bachman DJ, Whitlock EP, Hornbrook MC. Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1515–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Screening for perinatal depression. Committee Opinion No. 630. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1268–71. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000465192.34779.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84:478–85. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ko JY, Farr SL, Dietz PM, Robbins CL. Depression and treatment among U.S. pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005–2009. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:830–6. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Strat Y, Dubertret C, Le Foll B. Prevalence and correlates of major depressive episode in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:128–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Health and Human Services. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 2017 June 1]; Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.aspx.

- 16.Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, Oberlander TF, Dell DL, Stotland N, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:403–13. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disoders: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrellas NW, Biederman J, Uchida M. How prevalent and morbid are subthreshold manifestations of major depression in adolescents? A literature review J Affect Disord. 2017;210:166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7:3–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermens ML, van Hout HP, Terluin B, van der Windt DA, Beekman AT, van Dyck R, et al. The prognosis of minor depression in the general population: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang PS, Demler O, Kessler RC. Adequacy of treatment for serious mental illness in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:92–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young AS, Klap R, Shoai R, Wells KB. Persistent depression and anxiety in the United States: prevalence and quality of care. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1391–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegerl U, Schonknecht P, Mergl R. Are antidepressants useful in the treatment of minor depression: a critical update of the current literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:1–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834dc15d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dagher RK, Shenassa ED. Prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depression: is there an association? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15:31–7. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidson K, Jonas BS, Dixon KE, Markovitz JH. Do depression symptoms predict early hypertension incidence in young adults in the CARDIA study? Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1495–500. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman MP, Wright R, Watchman M, Wahl RA, Sisk DJ, Fraleigh L, et al. Postpartum depression assessments at well-baby visits: screening feasibility, prevalence, and risk factors. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14:929–35. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott KM, Von Korff M, Ormel J, Zhang MY, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, et al. Mental disorders among adults with asthma: results from the World Mental Health Survey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:123–33. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowan K, McAlpine DD, Blewett LA. Access and cost barriers to mental health care, by insurance status, 1999–2010. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1723–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercier A, Auger-Aubin I, Lebeau JP, Schuers M, Boulet P, Hermil JL, et al. Evidence of prescription of antidepressants for non-psychiatric conditions in primary care: an analysis of guidelines and systematic reviews. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]