Introduction

Expenditures on means-tested transfer programs in the United States have risen dramatically in recent decades (Moffitt 2015b; Ziliak 2015a). However, this growth in program outlays is not universal. For example, inflation-adjusted spending on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and the Additional Child Tax Credit (CTC) grew by 290, 59, and over 2200 % from 2000–2012, respectively.1 In contrast, real spending on cash assistance from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program declined, reflecting the transformation of the safety net away from cash-based assistance to one more reliant on refundable tax credits and in-kind food assistance (Bitler and Hoynes 2010; Hardy 2016; Moffitt 2013, 2015b; Ziliak 2015a). This spending pattern predated the Great Recession, suggesting that factors beyond the business cycle are potentially driving transfer program participation. These may include policy reforms affecting program eligibility and generosity, such as the 1990s welfare reform and expansion of EITC and creation of the CTC, the decline in full-time work, stagnant earnings, the rise in disability, and changing demographic trends leaving families vulnerable to economic risk (Meyer and Rosenbaum 2001; Piketty and Saez 2003; Gundersen and Ziliak 2004; Autor and Duggan 2006; Autor et al. 2008; Cancian and Reed 2009). Working alone or together, these demographic, macroeconomic, and policy forces might push the safety net towards a longer-term role as an income supplement for the working poor.

In this paper, we estimate the determinants associated with the growth in longer-term reliance on the safety net over the past 30 years. Specifically, we construct a series of two-year (biennial) panels from the 1981–2013 waves of the Current Population Survey’s (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to estimate the effect of state labor-market conditions, federal and state transfer-program policy choices, and household demographics governing joint participation of SNAP, the EITC, and the CTC. With the model estimates we then conduct a number of counterfactual simulations to assess the relative contributions of the economy, policy, and demographics on the dramatic rise in multiple transfer-program participation. We emphasize SNAP, the EITC, and CTC both because of the extraordinary growth in outlays, but also because of their ties to a more work-based safety net. SNAP, also known as food stamps, provides monthly benefits to support household purchases of food for preparation and consumption in the home. Eligibility for the program is income conditioned, and while it is open to workers and nonworkers alike, there has been strong secular growth in the fraction of the SNAP caseload combining benefits with work (Hoynes and Schanzenbach 2016). The EITC and Additional CTC are refundable tax credits that are received once per year after filing the tax return. Like SNAP, the EITC and CTC are income conditioned, but are available only to workers. Also distinguishing these three programs is the fact that they are highly liquid; SNAP is formally an in-kind program but benefits are treated as near cash by participants (Hoynes and Schanzenbach 2009). This stands in contrast to Medicare and Medicaid, two highly illiquid programs, or Social Security retirement and disability insofar as they are not conditional on sickness, age, or disability status. Moreover, unlike housing assistance, neither SNAP, EITC, or the CTC has waiting lists, so that all who are eligible should receive benefits if they apply.

Our empirical framework extends the prior literature in three substantive directions. First, previous research on SNAP and the EITC has relied upon annual repeated cross-sectional data that provide just a snapshot of program use (Meyer and Rosenbaum 2001; Bitler, Hoynes, and Kuka 2014; Ziliak 2015b). While cross-sectional research designs capture important, shorter-term conditions facing individuals and families, such as temporary job loss, our use of a panel permits us to study the factors driving less transitory, longer-term usage of transfer programs. While we are necessarily limited to two-year panels based on the design of the CPS, we demonstrate that there is churn in program use and secular biennial growth in program participation missing from the cross-sectional case.

Second, to our knowledge, we are the first to examine the factors affecting biennial multiple-program participation in SNAP, the EITC, and the CTC. Ziliak (2015b) focused solely on the factors driving the rise in SNAP participation in the cross-section, and Bitler, Hoynes, and Kuka (2014) focused on cross-sectional analysis of the EITC. Research on multiple program participation in the cross-section is scarce (Moffitt 2015a), let alone over time. Exceptions to this include recent work by Cancian et al. (2014) examining multiple program participation in Wisconsin through the lens of subsequent program disconnectedness, while Slack et al. (2014) examine how low-income families combine benefits in the post-Welfare Reform era. Slack et al. confirm that many households combine benefits and thus treat assistance as a package and not necessarily independent. Similarly, Moffitt (2015a) shows that among those receiving SNAP in the 2008–2009 Survey of Income and Program Participation, 38 % also received the EITC, and 28 % received the CTC. These percentages rise to 53 and 40 %, respectively, among the non-elderly, non-disabled SNAP population, and to 89 and 72 % among those with incomes between 50 and 100 % of the poverty line. By contrast, only 10–15 % of SNAP families in any one of these samples received TANF, again suggesting a shift to multiple-program participation that coincides with, or fosters, work such as SNAP, EITC, and the CTC. For completeness, we also report briefly on models inclusive of TANF and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a non-work conditioned disability program.2

Third, we examine a wider array of family structures at risk of transfer use, and we focus more directly on the role of stagnant wages and the shift away from full time work on participation. Our focus on families with children is motivated by the design of the American social welfare system, which is largely geared towards assisting adults with dependent children (Currie 2006). The key advantage of the ASEC is the comparatively large sample size permitting us to focus on demographic groups most likely at risk of participation in the safety net from 1980 onward, especially families with low incomes and/or skills, as well as families headed by a single mother—the focal demographic group targeted by the 1990s welfare reforms. Moreover, the ASEC is the official data set used to calculate poverty and income inequality—in effect offering a useful baseline off of which to assess and contextualize the predictors of participation in major social welfare programs.

We find evidence of significant growth in longer-term joint use of SNAP, the EITC, and the CTC, increasing 104 % across all families with children since 2000 so that by 2012, three years after the end of the Great Recession, nearly 1 in 16 American families with children relied on both programs across two years. This joint participation rate jumps to almost 1 in 5 families living below twice the federal poverty line, to over 1 in 8 among single mother families (regardless of their income level), and 1 in 9 among family heads with a high school degree or less. The model estimates suggest that SNAP operates as an unambiguous countercyclical policy with respect to state unemployment rates. Increases in the share of workers out of the labor force as well as the state median wage have led to decreases in joint SNAP, EITC, and CTC use, demonstrating the unique margins off of which the EITC operates relative to traditional cash welfare—persons out of work receive no benefit while lower earners are supplemented. We also find that increases in real maximum SNAP benefits are associated with the growth in joint program participation; the generosity of the EITC phase-in rate is positively associated with EITC and CTC program participation. This suggests that changes in the benefit structure of the programs have fostered the coupling of work with work-based assistance, while at the same time strengthening the safety net for vulnerable low skill families with children.

Combining the factors together, the simulations suggest that the majority of the increase in joint use of SNAP and EITC/CTC from 2000 to 2012 is associated neither with the cyclical nor structural aspects of the economy, nor changing demographics, and instead is attributed to changing policy in the SNAP and EITC programs. The primacy of policy holds for all subsamples, and stands in stark contrast from the factors accounting for the post-2000 growth in SNAP alone where cyclical and structural labor-market factors account for at least one-half of the growth, and demographics play a more prominent role. Importantly, we note that the former result of the importance of policy over the economy for the joint use of SNAP and EITC/CTC since 2000 is sensitive to whether we use parameters estimated over the entire three-decade period or from the post-2000 period alone. In the latter case, the state macroeconomy becomes the leading factor for joint program participation, suggesting a strengthening in the relationship between economic conditions and participation in SNAP, the EITC, and CTC in recent years.

Setting the Context: SNAP, EITC, CTC and the Work-Based Safety Net

Fundamental changes in the U.S. social policy landscape throughout the 1980s and 1990s significantly altered the economic rewards to work and to participation in transfer programs, affecting all segments of the low-income population—especially single-mother headed families. During his first campaign for president, then Governor Clinton pledged to “end welfare as we know it,” and upon election in 1992 states aggressively pursued waivers from federal rules governing their main cash welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). These changes were codified into federal law with passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (aka “welfare reform”) that eliminated the AFDC program and replaced it with TANF. TANF policies varied widely across states, but generally included a set of “carrots” and “sticks”. The former included both expanded liquid asset limits for eligibility and earnings disregards that permitted mothers to retain a higher fraction of benefits as their earnings increased, while the latter included, among others, work requirements and time limits for benefit receipt. Importantly, funding was converted from an open-ended entitlement financed by a federal-state matching grant under AFDC to a fixed (in nominal dollars) $16.5 billion federal block grant under TANF. States reconfigured their programs from one that primarily provided cash assistance to one that predominantly provides in-kind assistance such as child-care vouchers, workforce training, and marriage counseling, among others, and that is much less target efficient on assisting the poor (Bitler and Hoynes 2016).

Concurrent to the new cash welfare law were enhanced incentives for low-income persons to work via expansions in the EITC, the creation of the Additional CTC, and liberalization of eligibility for participation in SNAP. The EITC was established in 1975 as the first refundable credit in the federal tax code in a bid to increase the incentive to work by offsetting the regressive Social Security payroll tax among low-wage workers (Hotz and Scholz 2003). The size of the credit first rises with earnings, is then constant over a certain range, and finally is gradually phased out as earnings continue to increase. Provided that the credit amount exceeds taxes owed the balance gets refunded. Over time the implicit scope of the program expanded to one that not only spurred work, but also combated poverty. This occurred through a series of increases, first as part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, and then the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Acts of 1990 and 1993, the latter of which increased the generosity of the credit, especially for families with two or more qualifying children. Finally, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 created a new, higher credit for three or more qualifying children (Steuerle 2015; Bitler and Hoynes 2016). In tax year 2015 the maximum credit for a single headed household with two qualifying children was $5,548, or 40 % of earnings. It is estimated that 5–6 million persons are lifted out of poverty each year by the EITC, and over 9 million when the alternative poverty line from the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure is used (Nichols and Rothstein 2016).

At the same time as the TANF program was being rolled out, Congress passed the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 that introduced the Child Tax Credit. Initially the credit was worth up to $400 for each qualifying child under age 17, but through a series of legislative changes, the credit today is worth up to $1,000 for each qualifying child. It also has a refundable component if the amount of the CTC exceeds the amount of tax owed and (a) the household has three or more dependent children or (b) earned income exceeds $3,000 (CBO 2013b). As shown in Appendix Fig. 1, spending on the Additional CTC is now in excess of $30 billion annually and larger than TANF. The December 2015 federal budget agreement made all of these ARRA expansions in the EITC and CTC a permanent part of the income tax structure.

The 1996 welfare reform also affected SNAP rules. SNAP, originally known as the Food Stamp Program, was established in 1964 as a means of providing food assistance to low-income and low-asset households. Benefits are federally funded, with the maximum benefit varying by household size but constant across the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia. Initially households were required to meet two income tests—gross income less than 130 % of the poverty guideline for the household size, and net income below 100 % of the line—and two asset tests, one pertaining to holdings of liquid wealth (e.g. cash, checking, savings) and one to vehicle wealth. The gross income limit is waived for households containing a disabled person or with persons age 60 or older, and the liquid asset limit is higher for these households. There was no work requirement associated with benefit receipt and they were available to all legal residents who qualified. This changed with welfare reform, wherein restrictions on benefit receipt were imposed upon legal immigrants and so-called ABAWDS—able-bodied adults without dependents working less than 20 hours per week. The reform also reduced the maximum benefit and froze many deductions used in calculating net income; it allowed states to sanction individuals and households for noncompliance with TANF requirements or child support payments; and it mandated that states replace the paper coupons with the Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) debit cards. Take-up rates (i.e. participation rates among those eligible) plummeted from nearly 75 % before reform to just over 50 % five years after (Lefton, et al. 2011). In response, rule changes implemented first by USDA, and then within the 2002 Farm Bill passed by Congress, restored eligibility for most of the legal residents removed by the 1996 reform, liberalized financial eligibility rules (notably asset tests), and allowed states to utilize broad-based categorical eligibility that gave flexibility to apply more generous TANF asset and gross-income tests to determine SNAP eligibility. Many states also shifted to electronic applications, reducing the potential stigma associated with SNAP use. Furthermore, in the 2008 Farm Bill, states were given the option of increasing or removing both the vehicle and liquid asset tests. While all have removed the value of at least one vehicle from the test, upwards of 38 states have also eliminated liquid asset tests at some point over the past decade.3

Combined, the restrictions placed on cash welfare, alongside new incentives to work with EITC expansions and the introduction of the CTC, point to expected increases in program take-up, while the retrenchment of SNAP eligibility in the 1990s followed by the liberalization of program rules in the 2000s point to decadal-specific shifts in policy-induced program participation. For example, with respect to SNAP, Ganong and Leibman (2013) find that longer recertification periods—whereby recipients update information on income and eligibility—along with simplified reporting positively impact program take-up. Likewise, for the EITC, workers eligible for lower credits in the phase-in range are less likely to participate, as are those with less education (Jones 2014).

These policy reforms did not occur in isolation from broader macroeconomic and demographic trends. On the macroeconomic front, there have been four recessions since 1980—1981–82, 1991, 2001, and the Great Recession that officially spanned from December 2007 to June 2009—as well as three of the four longest economic expansions since World War II following these downturns. All else equal, participation in SNAP is expected to be counter-cyclical—rising when the economy is falling—as households experience declining earnings and other forms of economic hardship. However, participation in the EITC and CTC is less clear over the business cycle. Falling incomes from earnings and/or hours reductions could bring some workers and families into eligibility as low earners. This may be especially true for formerly EITC-ineligible married families that are buffered against economic shocks by the EITC when one worker faces economic hardship or job loss. On the other hand, if job loss occurs and results in a total loss of earnings, economic shocks associated with unemployment could result in lowered EITC and CTC participation. During economic expansions, low-skilled persons out of the labor force could be enticed to enter, potentially increasing EITC and CTC participation, while those working could receive wage and/or hours boosts that lift them out of eligibility. These potentially heterogeneous participation effects suggest that we should estimate our empirical model for different skill and income groups.

On top of the business-cycle shocks are important secular economic trends that could affect program participation. Inflation-adjusted wages have been stagnant or declining in the lower half of the wage distribution for the better part of four decades (Autor, Katz, and Kearney 2008), which could lead to greater long-term attachment to programs such as SNAP, the EITC, and the CTC. Likewise, detachment from the labor force for extended periods (continuous two-years) rose over four-fold from about 8 % to 38 % among less skilled men of prime working age (Ziliak, Hardy, and Bollinger 2011), which would at once lead to increases in SNAP and decreases in the EITC and CTC. This has been buttressed by strong secular growth in disability, again pulling toward higher SNAP and lower EITC and CTC, with spending on Social Security Disability and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) programs more than doubling in real terms since 2000 alone to nearly $200 billion annually (Autor and Duggan 2007).

The changing demographic makeup of the American household could also have potentially countervailing influences on trends in SNAP, the EITC, and CTC participation. Population aging and delays in childbirth each likely put downward pressure on program participation because take-up rates in means-tested programs are lower among older adults and those without children. Likewise, secular growth in high school completion and college attendance since 1980 also put downward pressure on SNAP program use, primarily because incomes and education are positively correlated, but may have resulted in greater take-up of EITC and CTC. On the other hand, the rise of out-of-wedlock childbirth and delay of marriage point toward increased reliance on public assistance because of greater economic need (Tach and Eads 2015). One would also expect an interaction between family structure and social policy reforms such as welfare reform and the EITC. Namely, as the 1996 welfare reform was aimed at reducing welfare use and increasing work among single-mother families, this demographic group should especially influence the growth in the EITC, CTC and SNAP. As such, we estimate the empirical model below separately for single mothers, the low-income, and the low-skilled.

Empirical Model and Data

Based on the discussion above, our objective is to model multi-year participation in SNAP, EITC, and CTC as a function of household demographic characteristics, the state macroeconomy, and state-level policy choices as

| (1) |

where is an indicator equal to 1 if anyone in household i residing in state j receives program k (k = joint SNAP, EITC, and CTC) in both time t and t+1; Xit is a vector of demographic characteristics of the household head in the initial period t; Zjt is a vector of state (or federal) by year economic and policy variables from period t; πjk is a set of indicators for each state to control for fixed, but unobserved state-specific factors affecting participation; φtk is a set of indicators for each year to control for macroeconomic and policy factors that affect all households the same in a given year but differ over time; and uijtk is a random error term. While our ultimate focus is on joint program participation, we also estimate Eq. (1) separately for SNAP alone and EITC plus CTC alone.

The primary data used in our study come from the CPS ASEC for calendar years 1980 to 2012 (interview years 1981 to 2013). The CPS is a monthly survey of the U.S. labor force based on a stratified random sample of 60,000 households, with the ASEC fielded in March of each year (and with some portion from the February and April samples) to collect information on household income, family structure, and health insurance in the prior calendar year. The CPS has a rotating sample design whereby respondents are in-sample for 4 months, out-of-sample for 8 months, and then in-sample for 4 more months. This makes it possible to match up to one-half of the sample from one ASEC interview to the next, creating a series of two-year (biennial) panels that form our measure of longer-term participation in welfare restricted to 20 to 55 year old individuals. Our final data set consists of 694,278 matches across the 30-year sample, with a match rate of 55 %. More detail on sample selection and longitudinal matching of the ASEC is provided in an online data appendix.4

In the ASEC, SNAP is asked at the household level; specifically, whether anyone in the household received SNAP in the last calendar year. It is possible for a household to contain more than one SNAP unit, or for only a subset of members to be on assistance. With our focus on the family we make the implicit assumption of resource sharing within the household such that all members benefit from SNAP even if they are not directly a recipient. Ziliak (2015b) shows that from 1980 to 2000, population-weighted participation rates were broadly comparable to administrative data, but over the past decade there has been a divergence in the levels, though not in trends (the levels gap was previously highlighted in Wheaton (2007) and Meyer et al. (2014)). Information on the EITC and the refundable portion of the CTC are not collected in the ASEC, and thus we rely on simulated eligibility based on the NBER’s TAXSIM model.5 The assumption in TAXSIM is that take-up rates are 100 %, when in fact they are closer to 80 %, though take-up in the EITC is lowest for those who receive a lower tax bill and not a refundable credit (Jones 2014). That is, for the EITC and CTC we focus on eligibility rates rather than actual participation, but for convenience we will refer to these as EITC/CTC participation rates. As we are interested in the persistence of participation over time, we construct an indicator of whether the family is receiving SNAP for both years they are in the sample. Since the CTC was not in effect until 1998, we combine these two refundable credits to construct an indicator for whether a family receives either or both the EITC or the CTC in both years (we refer to this combined program as EITC/CTC). Our broader measure of the safety net then is an indicator variable for whether the family receives SNAP and the EITC/CTC in both years.

We consider four subsamples for our analysis of safety net participation: all families; low-income families defined as having family income-to-needs below 200 % of the federal poverty line in each of the two years; low-education families defined as those whose head has a high school diploma or less; and single mother families, defined as those who mothers who head the family in both years. The longer-term low-income sample is of interest because federal gross-income eligibility for SNAP for the non-elderly is capped at 130 % of the household-specific poverty line, but since 2000 many states implemented broad-based categorical eligibility that lifted gross income tests to 150–200 % of the poverty line. Many low-income families fall within this category; roughly 1 in 4 sample respondents lie within this threshold for both years (see Appendix Table 3). Moreover, the under 200 % of poverty subpopulation is the group that generally qualifies for the EITC. However, we recognize that this low-income sample may be endogenous with SNAP and EITC/CTC participation in that the programs are means tested. Thus, we also present the low-education sample on the standard assumption that educational attainment is a proxy for permanent income, with high school or less signaling high-risk for program participation (Bloome and Western 2011; Corcoran 2001; Hoynes, et al. 2006). Last, we present the single mother subsample as this was the group most affected by the 1990s welfare reforms and expansion of the EITC/CTC.

The demographic controls in Eq. (1) include indicators for the household head’s age (ages 20–34 is the omitted group), education attainment (relative to high school dropout), race (relative to white), Hispanic ethnicity, female headship, and marital status (relative to widowed/separated/divorced/never married); the number of persons in the household (includes non-family members), the number of related children under age 18, residency within a metropolitan area, and within a metro area, residence in the central city to capture within-metro heterogeneity.6 All of these measures are based on year one of the match.

The measures of state labor-market conditions include the contemporaneous unemployment rate, along with one and two-year lags in order to capture potential business-cycle dynamics; the fraction of persons working full-time, part-time, and out of the labor force; and median wages as the focal measures of cyclical and structural changes in the macroeconomy. The key policy variables at the state and federal level include the larger of the real state or federal minimum wage rate, the maximum subsidy rate for the EITC based on year and number of qualifying children, whether the state offers a refundable state EITC, and the family-size specific maximum SNAP benefit. Even though it is set nationally, the EITC subsidy rate is identified by the fact that it varies over time and by the number of qualifying children (Hotz and Scholz 2003). For the SNAP policy variables, we assign the real maximum benefit guarantee for a 1, 2, 3, or 4 person household based on family size (the 4-person guarantee is assigned to households with 4 or more persons) to measure the financial generosity of the program. Like the EITC subsidy rate, the SNAP benefit is identified in the model because it varies over time and by household size.7 We also include indicators for: (i) whether a state implemented a waiver from its AFDC program; (ii) when its TANF program was implemented; (iii) a host of SNAP policy variables such as the fraction of SNAP dollars redeemed via the EBT, indicators for whether the state allows broad-based categorical eligibility, noncitizen SNAP eligibility, whether it imposes short recertification periods of 3 months or less for households with a working member, whether the household must be fingerprinted (either statewide or partial state), whether the household is disqualified for being sanctioned by another program such as TANF, whether the state adopted simplified reporting, whether it excludes the full value of a vehicle for eligibility, and the real value of spending on outreach; and (iv) whether the Governor was a Democrat.8 Our choice of SNAP policy variables is consistent with those employed throughout the literature (e.g. Ganong and Leibman 2013; Ratcliffe et al. 2008) to account for both positive and negative administrative and remunerative policy incentives driving program participation. Basic summary statistics on the variables used in the regression analysis for each sample are presented in Appendix Table 3.

Results

Biennial SNAP, EITC, and CTC Participation

We begin our results section with a descriptive analysis of two-year trends in SNAP, the EITC, and the CTC, and joint program participation. Because analysis of biennial program participation is a key contribution of our study, an examination of trends in participation is of interest on its own.

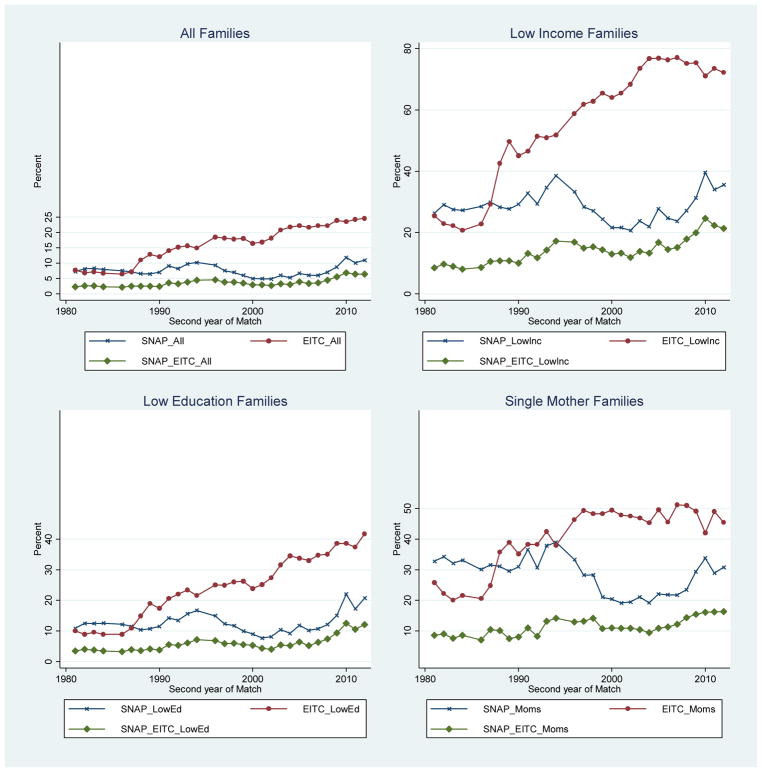

Figure 1 depicts trends in SNAP, EITC, and CTC, and combined SNAP and EITC/CTC participation for each of our samples across the two-year matches in the ASEC. Each of the panels in the figure shows strong secular increases in biennial use of the EITC/CTC starting after the first expansion in the Tax Reform Act of 1986, with a subsequent surge after the 1993 expansions (note the different scales for each panel). Over the whole sample period, biennial participation in the EITC/CTC more than doubled for the sample overall and for the low-income subsample, more than tripled for the low-education group, and rose a substantial 48 % among single mother families. There are substantive differences in the level of participation, with rates nearly twice as high among the low-income sample as compared to the low-skill sample, and with rates among single mothers falling in between (though closer to the low-skill rates). For the low-income sample, biennial participation in the EITC and CTC peaks in 2006, whereas for the single mother sample biennial participation in the EITC and CTC peaks in 2008 and has fallen in the subsequent years. For all families, EITC and CTC participation stabilizes towards the end of the sample period. While tax credit participation appears to be more secular than cyclical, we test this formally in our subsequent empirical analysis.

Figure 1.

Trends in Two-Year SNAP and EITC/CTC Participation

The biennial trends in SNAP in Fig. 1 are considerably different than the EITC and CTC. First, much like one finds in annual participation rates in Ziliak (2015b), there is evidence that biennial SNAP participation responds counter-cyclically with the health of the macroeconomy, with increases evident in the years surrounding recessions. This holds across all four samples. Second, changes in SNAP participation from 1981 to 2012 are substantial, though at a 50 % increase, growth in participation lags behind the overall rise in EITC and CTC participation. And, in fact, among single mothers, biennial SNAP participation rates fell 3 percentage points over the past 30 years. Third, biennial SNAP participation increased aggressively in response to the Great Recession, and remains at elevated levels.

Rates of joint participation in SNAP, EITC, and CTC are lower than either program in isolation. However, there was a dramatic 180 % increase in joint participation over the past three decades across all families, led in part by the 250 % increase from 3.5 % to 12.1 % among low-skilled family heads. Among single mothers, the 90 % increase in joint program participation meant that by 2012 16 % of single mother families relied on both programs for consecutive years. The figure suggests that joint participation moves with the business cycle more like SNAP than the EITC, and again like SNAP alone, there was a very substantial increase in joint participation with the onset of the Great Recession.

In order to further assess and decompose the prevalence of biennial program use, we construct a transition matrix of program participation, shown in Appendix Table 4. The rows in the table sum to 100 %, subject to rounding error. In it, we find that during the 1980s 47 % of families receiving SNAP and EITC/CTC in year 1 subsequently receive both programs in year 2. Year 2 dual program participation, conditional on year 1 participation, subsequently rises to 52 % of families in the 1990s and 54 % of families in the 2000s. We also see a fair amount of churn in program use across years. For example, SNAP receipt in year 1 seems to be more of a gateway to joint program use in year 2 (because individuals combine work and SNAP) than year 1 EITC participation alone, and joint program use in year 1 is more likely to result in EITC alone in year 2 than SNAP alone.

Employment and Wages

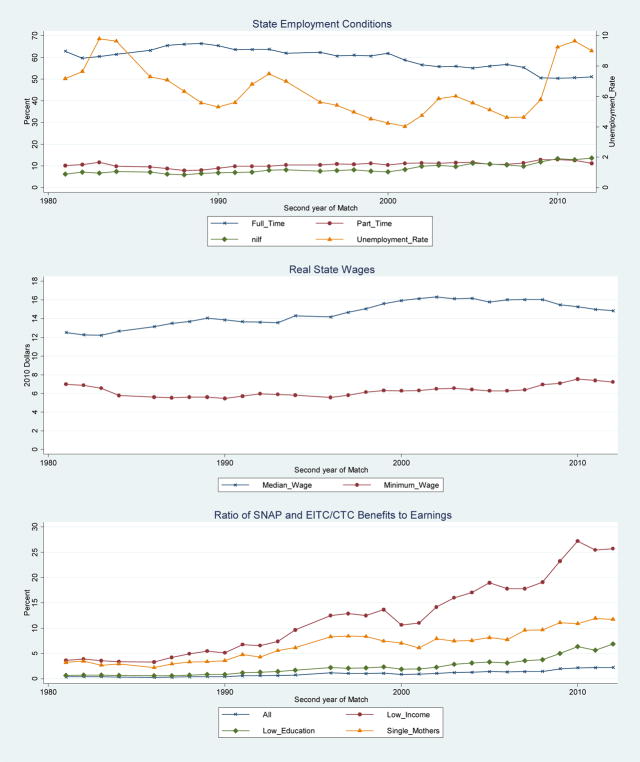

Because eligibility for participation in the EITC and CTC is work conditioned and income tested, and SNAP is means tested, an obvious place to look for evidence of changes in participation in those programs is changes in macroeconomic labor-market conditions. The top panel of Fig. 2 presents trends in state unemployment rates (right-axis) along with state-level averages in the fraction of the sample with continuous (i.e. biennial) full-time employment, continuous part-time employment, and continuous status of not in the labor force (nilf). The unemployment rate series is that estimated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics from the CPS, Current Employment Statistics, and state Unemployment Insurance claims data.9 The full-time, part-time, and not-in-labor-force series are estimated from our CPS sample of matched individuals (i.e. 465,091 pairs) and aggregated up to capture state differences over time in employment opportunities as reflected in the intensity of labor-market attachment.

Figure 2.

Trends in Employment, Wages and Benefit Replacement Rates

There are substantial swings in state unemployment rates with the business cycle in Fig. 2, and these swings coincide with changes in biennial SNAP participation in the previous figure. Importantly, while the peak unemployment rate in the Great Recession actually was slightly below that of the 1981–82 recession, the run-up of unemployment in the most recent downturn was much larger, and recovery much smaller, each of which could account for the sustained levels of transfer-program participation in the 2000s. Likewise, there are substantive changes in state labor-market opportunities over time in terms of full-time and part-time employment, and complete labor-force exit. While a cyclical component of continuous full-time employment is in evidence in the figure, there also appears to be a change in secular trends, with the pre-2000 period exhibiting increases in biennial full-time work, and then a reversal in the post-2000 period. The latter seems to have been met more by a secular increase in labor-force withdrawal than in part-time work. This could help account for the more rapid growth in SNAP compared to the EITC and CTC since SNAP has no explicit work requirement (except for ABAWDS).

The second panel of Fig. 2 depicts trends in state-level compensation for low- and middle-skill workers. Specifically, we present inflation-adjusted state minimum hourly wage rates along with the inflation-adjusted state median biennial average hourly wage.10 The figure shows that the first two decades of the sample were a period of secular growth in median wages, but since 2000 there has been a flattening out and then decline in hourly wages of the typical worker—the median real wage in 2012 was the same as in 1998. Wage opportunities among the least skilled also declined sharply in real terms in the 1980s when the nominal federal minimum remained fixed at $3.35 per hour and few states’ minimum wages deviated from the federal rate. It then held steady for the next eighteen years until the Great Recession when both the federal government and states increased the minimum. However, the average real state minimum wage was actually ten cents per hour lower in 2012 than in 1981. The stagnation of wages in the bottom half of the income distribution points both to increased eligibility and need for assistance from SNAP and the EITC and CTC.

To gauge the importance of this growth in biennial joint program participation for family budgets, the bottom panel of Fig. 2 presents trends in the ratio of biennial average benefits from SNAP, the EITC, and the CTC to biennial average family earnings among those with positive labor earnings in both years. The figure makes clear that the programs are increasingly “filling the gap” for low-income and low-skill families. Assistance from these programs had the effect of raising family earnings by 25 % in 2012 among low-income families—a 9-fold increase from three decades earlier.

Regression Results

We next turn to our regression results from estimating Eq. (1) via linear probability, where we correct the standard errors for heteroskedasticity and within-state autocorrelation arising from the fact that multiple households are present in each state. All models control for fixed state and year effects and are weighted using person level sampling weights adjusted for the probability of year 2 selection on observable demographics, conditional on year 1 selection.

Table 1 presents estimates for the biennial SNAP participation models for each of the four samples. Comparing across columns there is considerable consistency in the marginal effects of the family-level variables on the probability of participating in SNAP for two consecutive years. Namely, participation in SNAP is lower for older heads, those with higher education attainment, for whites and non-Hispanics, for larger households, and for married heads. Participation is higher for female-headed families and for families with more related children under age 18. We note that the magnitude of the coefficients differs because the baseline probabilities vary substantially across samples—average SNAP participation is 0.084, 0.302, 0.139, and 0.287 for the sample overall, for low-income, low-education, and single mother headed families, respectively (see Appendix Table 3).

Table 1.

Linear Probability Estimates of Biennial SNAP Participation

| VARIABLES | All Families | Low-Income Families | Low-Education Families | Single Mother Families |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Level | ||||

| Ages 28–35 | −0.0860** (0.004) |

−0.0926** (0.006) |

−0.0935** (0.005) |

−0.1439** (0.007) |

| Ages 36–44 | −0.1092** (0.006) |

−0.1176** (0.009) |

−0.1177** (0.008) |

−0.1934** (0.011) |

| Ages 45–55 | −0.0962** (0.006) |

−0.0987** (0.013) |

−0.0974** (0.008) |

−0.1933** (0.013) |

| High School Diploma | −0.1179** (0.005) |

−0.1265** (0.009) |

−0.1096** (0.004) |

−0.2081** (0.006) |

| Some College | −0.1434** (0.006) |

−0.1589** (0.012) |

−0.2748** (0.011) |

|

| College Graduate | −0.1527** (0.006) |

−0.2402** (0.014) |

−0.3648** (0.011) |

|

| Black | 0.0831** (0.007) |

0.1052** (0.013) |

0.1040** (0.011) |

0.1194** (0.012) |

| Other Race | 0.0317** (0.007) |

0.0590* (0.024) |

0.0355* (0.015) |

0.0304* (0.013) |

| Hispanic | 0.0077 (0.016) |

−0.0115 (0.030) |

0.0118 (0.019) |

0.0359 (0.029) |

| Household Size | −0.0219** (0.002) |

−0.0339** (0.003) |

−0.0255** (0.003) |

−0.0456** (0.005) |

| Number of Own Kids < Age 18 | 0.0557** (0.002) |

0.0749** (0.003) |

0.0741** (0.002) |

0.1222** (0.004) |

| Female Head | 0.0484** (0.003) |

0.0990** (0.008) |

0.0790** (0.005) |

|

| Married Head | −0.1539** (0.007) |

−0.1780** (0.010) |

−0.1844** (0.009) |

|

| Lives in Metro Area | −0.0141** (0.003) |

−0.0113 (0.009) |

−0.0192** (0.005) |

−0.0453** (0.011) |

| Lives in Central City | 0.0212** (0.005) |

0.0197 (0.015) |

0.0239** (0.008) |

0.0386** (0.012) |

| State/Federal Level | ||||

| State Unemployment Rate (UR) | 0.1703 (0.182) |

0.7645 (0.586) |

0.1091 (0.303) |

0.7835 (0.788) |

| 1 Year Lagged State UR | −0.0757 (0.220) |

−0.3199 (0.711) |

−0.0172 (0.324) |

0.0599 (0.873) |

| 2 year Lagged State UR | 0.5362** (0.122) |

1.5629** (0.424) |

0.7809** (0.195) |

1.2783** (0.460) |

| State % Full Year Worker | −0.0316 (0.036) |

0.0756 (0.126) |

−0.0366 (0.065) |

0.0327 (0.140) |

| State % Part Year Worker | 0.0620 (0.051) |

0.2445 (0.168) |

0.1240 (0.088) |

−0.1327 (0.178) |

| State % Not in Labor Force | 0.2015** (0.065) |

0.5287* (0.209) |

0.2813* (0.108) |

0.3139 (0.201) |

| State Median Wage | −0.0007 (0.001) |

0.0016 (0.004) |

−0.0016 (0.002) |

−0.0016 (0.003) |

| State Minimum Wage | −0.0029 (0.002) |

−0.0048 (0.008) |

−0.0086* (0.005) |

0.0016 (0.008) |

| EITC Subsidy Rate | −0.4042** (0.062) |

−0.1791 (0.202) |

−0.3508** (0.098) |

−0.5125** (0.180) |

| State Has Refundable EITC | −0.0044 (0.005) |

−0.0253 (0.016) |

−0.0113 (0.008) |

−0.0169 (0.015) |

| Any Welfare Reform Waiver | −0.0052 (0.005) |

−0.0198 (0.017) |

−0.0090 (0.011) |

−0.0037 (0.017) |

| TANF Implementation | −0.0268** (0.008) |

−0.0805** (0.028) |

−0.0148 (0.018) |

−0.0721* (0.032) |

| Max SNAP Benefit ($100s) | 0.0286** (0.003) |

0.0267** (0.005) |

0.0250** (0.005) |

0.0213** (0.005) |

| Implementation of EBT Card | 0.0006 (0.004) |

0.0103 (0.018) |

−0.0018 (0.008) |

0.0089 (0.015) |

| Broad-Based Eligibility | 0.0026 (0.005) |

−0.0061 (0.012) |

−0.0039 (0.008) |

0.0142 (0.018) |

| Short Certification | −0.0009 (0.004) |

−0.0058 (0.014) |

−0.0080 (0.009) |

−0.0045 (0.014) |

| Requires Fingerprinting | −0.0002 (0.005) |

0.0158 (0.016) |

0.0008 (0.009) |

0.0057 (0.014) |

| Compulsory Disqualification | 0.0036 (0.004) |

0.0075 (0.012) |

0.0091 (0.007) |

−0.0087 (0.012) |

| Simplified Reporting | 0.0128* (0.006) |

0.0577** (0.020) |

0.0366** (0.011) |

0.0399† (0.022) |

| Vehicle Assets Excludable | 0.0024 (0.005) |

0.0220 (0.015) |

0.0129 (0.008) |

−0.0016 (0.015) |

| Outreach ($100 millions) | −0.0033** (0.001) |

−0.0084** (0.003) |

−0.0043** (0.001) |

−0.0135** (0.002) |

| Noncitizens SNAP-eligible | −0.0005 (0.005) |

−0.0120 (0.013) |

0.0004 (0.007) |

0.0029 (0.011) |

| Governor is Democrat | 0.0055** (0.002) |

0.0180** (0.005) |

0.0083** (0.003) |

0.0147* (0.006) |

| SELECTED ELASTICITY CALCULATIONS FOR SNAP PARTICIPATION | ||||

| State Unemployment | 0.473 | 0.439 | 0.408 | 0.473 |

| State % Full Year Worker | −0.225 | 0.076 | −0.137 | 0.043 |

| State % Part Year Worker | 0.078 | 0.143 | 0.105 | −0.070 |

| State % Not in Labor Force | 0.204 | 0.378 | 0.239 | 0.199 |

| State Median Wage | −0.121 | 0.075 | −0.163 | −0.081 |

| State Minimum Wage | −0.225 | −0.104 | −0.402 | 0.036 |

| EITC Subsidy Rate | −1.270 | −0.158 | −0.626 | −0.484 |

| State Has Refundable EITC | −0.006 | −0.009 | −0.008 | −0.008 |

| Any Welfare Reform Waiver | −0.003 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.001 |

| TANF Implementation | −0.140 | −0.115 | −0.041 | −0.118 |

| Max SNAP Benefit ($100s) | 1.616 | 0.410 | 0.844 | 0.304 |

| Observations | 176,072 | 39,596 | 80,574 | 27,522 |

| R-squared | 0.229 | 0.186 | 0.252 | 0.244 |

Standard errors in parenthesis control for heteroskedasticity and within-state autocorrelation. All models control for fixed state and time effects.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Elasticities are calculated at mean values by group for the selected policy variables.

The estimates in Table 1 provide strong evidence that biennial SNAP participation is countercyclical with respect to the state unemployment rate, which is consistent with annual estimates from pooled cross-sectional data (Ganong and Liebman 2013; Ziliak 2015b). For example, in the full sample a one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate that persists two years leads to a 0.63 point increase in biennial SNAP participation (the sum of the three coefficients on the unemployment rate).11 It is often more convenient to express this as an elasticity.12 The elasticity of continuous SNAP participation with respect to the 2 year lagged unemployment rate is 0.47 for the full sample of family heads (see bottom of Table 1 for elasticities); that is, a 10 % increase in unemployment results in a 4.7 % increase in biennial SNAP participation. This business cycle relationship persists for the remaining categories, with an elasticity range of 0.44 (low income heads) to 0.47 (single-mother heads). The positive relationship between the proportion of the state’s labor market that is out-of-the-labor force and continuous SNAP participation rates is statistically significant for all but single mother headed families, and their SNAP out-of-the-labor force elasticity is 0.20, which is similar to that of all heads (0.20) and less educated heads (0.24) and less than low income heads (0.38). These results are broadly consistent with those in Ziliak (2015b) and Bitler and Hoynes (2016), showing that SNAP performs in a countercyclical nature—with unemployment as the business cycle indicator—during the Great Recession. We find this result holds for unemployment as well as the proportion out of the labor force, and that this occurs over a 30-year period inclusive of but not limited to the 2007–2009 Great Recession. In these and remaining empirical models, we depart from Ziliak (2015b) by estimating a broader set of structural economic, policy, and demographic variables for dual program participation over two years, including additional controls for part-time employment, labor force status, and an indicator for state EITC—stratified by the adult head’s income level, educational attainment, and marital status.

Across all samples except low-income, increased generosity of the EITC leads to lower continuous SNAP use, with elasticities ranging from −1.27 in the full sample to −0.48 among single mothers. Because the generosity of the recipient’s SNAP benefit is not reduced by the size of the EITC, this reflects a behavioral response to increasing work and reducing food stamps rather than a mechanical relationship between the EITC and SNAP allotments. On the other hand, increases in the generosity of the SNAP benefit lead to increases in SNAP participation for all samples, consistent with demand theory. The elasticity of continuous participation with respect to the SNAP benefit generosity ranges from 0.30 for single mothers and 0.84 for low-skilled heads, to 1.62 for the sample overall. The greater responsiveness of the full sample compared to the more disadvantaged subsamples stems in part from more permanence in SNAP use among disadvantaged groups. Most of the other SNAP policy variables have no statistically significant effect on continuous participation, with a few exceptions such as simplified reporting and outreach spending.13 Across all samples, residing in a state with a Democrat as Governor is associated with higher odds of continuous SNAP use, which may reflect overall state climate governing program access.

Table 2 contains the parallel set of results for biennial participation in the EITC and CTC programs. In general the results of the family-level demographic factors are similar between the SNAP models of Table 1 and the EITC/CTC models of Table 2, with some notable exceptions where low-income and single-mother families differ from the low-skilled and families in general. For example, among these families there is no significant difference between older and younger heads, but participation is increasing in education attainment, and is higher among married heads. The positive association between education and EITC/CTC use among the poor is consistent both with greater program knowledge and labor-force attachment (Chetty et al. 2013; Moffitt 2015b).

Table 2.

Linear Probability Estimates of Biennial EITC/CTC Participation

| VARIABLES | All Families | Low-Income Families | Low-Education Families | Single Mother Families |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Level | ||||

| Ages 28–35 | −0.0629** (0.007) |

0.0171 (0.010) |

−0.0423** (0.008) |

0.0067 (0.016) |

| Ages 36–44 | −0.0936** (0.008) |

0.0125 (0.011) |

−0.0726** (0.009) |

−0.0298 (0.020) |

| Ages 45–55 | −0.0916** (0.007) |

−0.0188† (0.011) |

−0.0713** (0.007) |

−0.0568** (0.016) |

| High School Diploma | −0.0774** (0.010) |

0.0241** (0.007) |

−0.0741** (0.008) |

0.0406** (0.013) |

| Some College | −0.1188** (0.013) |

0.0400** (0.008) |

0.0020 (0.013) |

|

| College Graduate | −0.1816** (0.011) |

0.0122 (0.015) |

−0.2183** (0.011) |

|

| Black | 0.0372** (0.007) |

−0.0182 (0.013) |

0.0390** (0.009) |

0.0078 (0.013) |

| Other Race | 0.0378** (0.006) |

−0.0003 (0.016) |

0.0312** (0.011) |

0.0071 (0.023) |

| Hispanic | 0.1122** (0.016) |

0.0491† (0.027) |

0.1234** (0.023) |

0.0329 (0.023) |

| Household Size | −0.0092* (0.004) |

−0.0213** (0.007) |

−0.0100† (0.006) |

−0.0089* (0.004) |

| Number of Own Kids < Age 18 | 0.0446** (0.004) |

−0.0224** (0.007) |

0.0476** (0.006) |

0.0197** (0.007) |

| Female Head | 0.0321** (0.003) |

0.0045 (0.010) |

0.0438** (0.006) |

|

| Married Head | −0.1478** (0.014) |

0.0537** (0.012) |

−0.1173** (0.016) |

|

| Lives in Metro Area | −0.0499** (0.004) |

−0.0131 (0.010) |

−0.0537** (0.006) |

−0.0882** (0.012) |

| Lives in Central City | 0.0068 (0.007) |

−0.0229 (0.015) |

0.0049 (0.009) |

−0.0055 (0.014) |

| State/Federal Level | ||||

| State Unemployment Rate (UR) | −0.2222 (0.165) |

−0.4393 (0.315) |

−0.4701* (0.218) |

−0.8798* (0.405) |

| 1 Year Lagged State UR | 0.1823 (0.286) |

−0.2015 (0.675) |

0.4810 (0.424) |

−0.2477 (0.808) |

| 2 year Lagged State UR | 0.1887 (0.188) |

0.6851 (0.510) |

0.4229 (0.328) |

0.5509 (0.615) |

| State % Full Year Worker | −0.0289 (0.060) |

0.1352 (0.150) |

−0.0676 (0.088) |

−0.0514 (0.153) |

| State % Part Year Worker | 0.1651* (0.077) |

0.4578* (0.178) |

0.2298* (0.113) |

0.2257 (0.224) |

| State % Not in Labor Force | −0.2067* (0.078) |

−0.8560** (0.224) |

−0.3306* (0.146) |

−1.0496** (0.259) |

| State Median Wage | −0.0119** (0.002) |

−0.0168** (0.005) |

−0.0147** (0.003) |

−0.0286** (0.006) |

| State Minimum Wage | 0.0008 (0.004) |

0.0049 (0.010) |

0.0120* (0.006) |

−0.0065 (0.010) |

| EITC Subsidy Rate | 1.1056** (0.073) |

1.5172** (0.158) |

1.5727** (0.112) |

1.6342** (0.187) |

| State Has Refundable EITC | −0.0057 (0.004) |

−0.0033 (0.013) |

−0.0147† (0.008) |

0.0122 (0.013) |

| Any Welfare Reform Waiver | −0.0018 (0.008) |

0.0182 (0.024) |

0.0114 (0.015) |

0.0109 (0.029) |

| TANF Implementation | 0.0160 (0.015) |

0.0407 (0.034) |

0.0336 (0.023) |

0.1006* (0.042) |

| Max SNAP Benefit ($100s) | −0.0465** (0.003) |

−0.0222** (0.006) |

−0.0647** (0.005) |

−0.0328** (0.007) |

| Implementation of EBT Card | −0.0004 (0.006) |

0.0052 (0.020) |

−0.0110 (0.010) |

0.0481** (0.018) |

| Broad-Based Eligibility | 0.0066 (0.005) |

0.0004 (0.018) |

0.0093 (0.011) |

0.0240 (0.016) |

| Short Certification | −0.0047 (0.005) |

−0.0112 (0.014) |

−0.0107 (0.010) |

0.0042 (0.015) |

| Requires Fingerprinting | 0.0046 (0.006) |

0.0052 (0.016) |

0.0101 (0.011) |

0.0011 (0.013) |

| Compulsory Disqualification | −0.0005 (0.004) |

0.0016 (0.014) |

0.0021 (0.009) |

0.0054 (0.016) |

| Simplified Reporting | −0.0006 (0.007) |

−0.0051 (0.020) |

−0.0144 (0.014) |

−0.0193 (0.020) |

| Vehicle Assets Excludable | −0.0031 (0.005) |

−0.0206 (0.017) |

−0.0099 (0.010) |

−0.0006 (0.015) |

| Outreach ($100 millions) | −0.0021 (0.002) |

−0.0014 (0.007) |

−0.0036 (0.005) |

0.0097** (0.002) |

| Noncitizens SNAP-eligible | 0.0019 (0.008) |

0.0452* (0.019) |

0.0118 (0.014) |

0.0030 (0.018) |

| Governor is Democrat | 0.0006 (0.003) |

0.0010 (0.006) |

−0.0022 (0.004) |

0.0022 (0.007) |

| SELECTED ELASTICITY CALCULATIONS FOR EITC/CTC PARTICIPATION | ||||

| State Unemployment | 0.058 | 0.005 | 0.121 | −0.096 |

| State % Full Year Worker | −0.106 | 0.077 | −0.151 | −0.051 |

| State % Part Year Worker | 0.106 | 0.152 | 0.116 | 0.088 |

| State % Not in Labor Force | −0.108 | −0.347 | −0.167 | −0.495 |

| State Median Wage | −1.058 | −0.445 | −0.894 | −1.074 |

| State Minimum Wage | 0.032 | 0.060 | 0.335 | −0.110 |

| EITC Subsidy Rate | 1.791 | 0.757 | 1.674 | 1.147 |

| State Has Refundable EITC | −0.004 | −0.001 | −0.006 | 0.004 |

| Any Welfare Reform Waiver | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| TANF Implementation | 0.043 | 0.033 | 0.055 | 0.122 |

| Max SNAP Benefit ($100s) | −1.354 | −0.193 | −1.304 | −0.348 |

| Observations | 176,072 | 39,596 | 80,574 | 27,522 |

| R-squared | 0.199 | 0.162 | 0.173 | 0.106 |

Standard errors in parenthesis control for heteroskedasticity and within-state autocorrelation. All models control for fixed state and time effects.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Elasticities are calculated at mean values by group for the selected policy variables.

Among the state and federal economic and policy variables, there are also several key differences from the SNAP models. For example, across all samples the quantitative effect of state unemployment rates on EITC and CTC participation is considerably smaller in absolute value than the SNAP alone models (see the elasticities in the lower panel) and generally statistically insignificant. This implies that SNAP functions more as an automatic stabilizer than refundable tax credits. This is further underscored by the different qualitative associations—EITC and CTC participation is generally a-cyclical with respect to the state unemployment rate as demonstrated by the elasticities.14,15 Another key difference in Table 2 from the SNAP models is the consistently strong effect of the share of part-time workers on the odds of continuous EITC and CTC participation, buttressing the result that the program serves as a longer-term work support for those in longer-term part-time employment.

The estimates in Table 2 show economically important own and cross-price effects with respect to program generosity. That is, continuous participation in the EITC/CTC is strongly positively associated with the generosity of the EITC phase-in subsidy rate, and negatively associated with the generosity of SNAP (though smaller in absolute value). As shown in Appendix Table 3 there are large differences in biennial participation rates in the EITC and CTC across samples, ranging from 16 % among all families to 53 % among low-income families. The associated elasticities of continuous EITC/CTC participation with respect to the phase-in rate range from 1.15 among single mother families to 0.76 among low-income families. The estimate for single mothers is equivalent to the estimate of 1.1 in Meyer and Rosenbaum (2001), even though our study differs in that we are examining both the EITC and CTC for two consecutive years as opposed to single-year use of the EITC alone, and our study covers an additional 18 years of data when single mothers’ employment rates were much higher than in the 1980s and early 1990s. To our knowledge we are the first to estimate such elasticities for the wider low-skilled and low-income populations. The corresponding elasticities of EITC/CTC with respect to the SNAP maximum benefit range from −0.19, −0.35, −1.30, and −1.35 for low-income, single-mother, low-skill headed families, and all families, respectively.

We find positive associations of TANF implementation with continuous EITC/CTC participation among single-mother family heads, which aligns with the wider cross-sectional welfare literature that found higher labor force participation in response to TANF implementation (Blank 2009). SNAP policy has no additional consistent association with EITC participation across groups when examining the remaining policies, as neither program benefit is counted as resources in determining the other program’s benefit.

Table 3 examines the determinants of joint participation in SNAP, EITC, and the CTC across two years. Here we see an interesting mix of estimates where in some cases the coefficients align with the SNAP-alone models and others the EITC/CTC models. For example, qualitatively all of the coefficients on the demographic factors align with the continuous SNAP models, though the magnitudes are attenuated for age, education, race/ethnicity, household size, gender, and marital status. Also notable is the fact that joint participation in SNAP, EITC, and CTC is countercyclical, similar to our findings in the SNAP-alone models, and though the coefficients are smaller in magnitude, the corresponding elasticities for biennial lagged unemployment at the mean are comparable, ranging from 0.31 to 0.39.16 The proportion of the state’s labor market that is out-of-the-labor force is now negatively related to joint participation—reflecting the direct relationship between EITC and work. This is consistent with recent work examining EITC eligibility by Jones (2015), who finds that less-educated, single females are likely to experience reduced EITC due to job loss during the Great Recession. Related to this, higher state median wages are now associated with a lowered likelihood of joint program participation, with sizable elasticities; higher earner workers are eventually disqualified from both EITC and CTC and SNAP receipt. The EITC subsidy rate has a much more muted effect on joint participation. The positive coefficient on the maximum SNAP benefit guarantee, like we observed in Table 1, is suggestive that more generous SNAP benefits are associated with higher rates of persistent use of joint program use, underscoring the importance of these programs to the work-based safety net. Although most of the other state SNAP policies have a qualitative positive effect on joint participation, with few exceptions they are not individually statistically significant. Vehicle assets stand out as a formerly unimportant policy in the SNAP-alone models that now positively predict SNAP and EITC/CTC participation for all groups except the full sample, and outreach spending has the expected positive sign. Again as in Table 1, residing in a state with a Democrat as Governor is positively associated with biennial multiple program participation.

Table 3.

Linear Probability Estimates of Biennial SNAP and EITC/CTC Participation

| VARIABLES | All Families | Low-Income Families | Low-Education Families | Single Mother Families |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Level | ||||

| Ages 28–35 | −0.0385** (0.005) |

−0.0393** (0.007) |

−0.0388** (0.005) |

−0.0412** (0.012) |

| Ages 36–44 | −0.0500** (0.006) |

−0.0520** (0.011) |

−0.0498** (0.007) |

−0.0591** (0.013) |

| Ages 45–55 | −0.0482** (0.005) |

−0.0590** (0.011) |

−0.0456** (0.007) |

−0.0711** (0.014) |

| High School Diploma | −0.0405** (0.004) |

−0.0369** (0.007) |

−0.0395** (0.003) |

−0.0429** (0.007) |

| Some College | −0.0498** (0.004) |

−0.0350** (0.010) |

−0.0597** (0.008) |

|

| College Graduate | −0.0594** (0.004) |

−0.0887** (0.013) |

−0.1071** (0.008) |

|

| Black | 0.0295** (0.004) |

0.0355** (0.010) |

0.0364** (0.006) |

0.0424** (0.009) |

| Other Race | 0.0112** (0.004) |

0.0092 (0.012) |

0.0085 (0.007) |

−0.0001 (0.013) |

| Hispanic | 0.0053 (0.008) |

−0.0168 (0.015) |

0.0045 (0.011) |

−0.0032 (0.010) |

| Household Size | −0.0041** (0.001) |

−0.0054† (0.003) |

−0.0035† (0.002) |

−0.0092* (0.004) |

| Number of Own Kids < Age 18 | 0.0196** (0.002) |

0.0189** (0.004) |

0.0245** (0.003) |

0.0273** (0.005) |

| Female Head | 0.0134** (0.001) |

0.0251** (0.006) |

0.0205** (0.002) |

|

| Married Head | −0.0554** (0.004) |

−0.0454** (0.008) |

−0.0566** (0.006) |

|

| Lives in Metro Area | −0.0097** (0.003) |

−0.0064 (0.009) |

−0.0107* (0.004) |

−0.0282** (0.009) |

| Central City | 0.0016 (0.003) |

−0.0103 (0.010) |

−0.0030 (0.005) |

0.0005 (0.007) |

| State/Federal Level | ||||

| State Unemployment Rate (UR) | −0.0235 (0.127) |

−0.0232 (0.461) |

−0.1360 (0.203) |

0.1384 (0.437) |

| 1 Year Lagged State UR | −0.1321 (0.159) |

−0.5327 (0.543) |

0.0556 (0.215) |

−0.7222 (0.642) |

| 2 year Lagged State UR | 0.3515** (0.100) |

1.2749** (0.313) |

0.4282** (0.146) |

1.1186* (0.456) |

| State % Full Year Worker | −0.0477 (0.030) |

−0.0459 (0.103) |

−0.0707 (0.047) |

−0.0809 (0.124) |

| State % Part Year Worker | 0.0441 (0.043) |

0.2230 (0.164) |

0.0712 (0.064) |

−0.0795 (0.165) |

| State % Not in Labor Force | −0.1143* (0.055) |

−0.4952** (0.179) |

−0.2103† (0.106) |

−0.5098* (0.202) |

| State Median Wage | −0.0035** (0.001) |

−0.0101** (0.003) |

−0.0066** (0.002) |

−0.0095** (0.003) |

| State Minimum Wage | 0.0005 (0.002) |

0.0053 (0.007) |

−0.0003 (0.003) |

0.0077 (0.007) |

| EITC Subsidy Rate | 0.0066 (0.051) |

0.1210 (0.143) |

0.1449 (0.087) |

0.1705 (0.142) |

| State Has Refundable EITC | 0.0001 (0.003) |

0.0005 (0.013) |

−0.0053 (0.006) |

0.0114 (0.013) |

| Any Welfare Reform Waiver | 0.0009 (0.005) |

0.0000 (0.017) |

−0.0009 (0.006) |

0.0167 (0.018) |

| TANF Implementation | −0.0112 (0.008) |

−0.0328 (0.028) |

0.0027 (0.012) |

−0.0066 (0.033) |

| Max SNAP Benefit ($100s) | 0.0068** (0.002) |

0.0135** (0.003) |

0.0029 (0.003) |

0.0151** (0.004) |

| Implementation of EBT Card | −0.0020 (0.003) |

0.0009 (0.011) |

−0.0060 (0.006) |

0.0094 (0.013) |

| Broad-Based Eligibility | 0.0032 (0.004) |

0.0022 (0.012) |

−0.0030 (0.008) |

0.0059 (0.015) |

| Short Certification | −0.0006 (0.003) |

−0.0023 (0.011) |

−0.0055 (0.008) |

−0.0025 (0.011) |

| Requires Fingerprinting | 0.0033 (0.004) |

0.0119 (0.011) |

0.0023 (0.007) |

0.0032 (0.011) |

| Compulsory Disqualification | 0.0018 (0.004) |

0.0091 (0.012) |

0.0058 (0.007) |

−0.0039 (0.012) |

| Simplified Reporting | 0.0095* (0.004) |

0.0369* (0.015) |

0.0222** (0.008) |

0.0324† (0.016) |

| Vehicle Assets Excludable | 0.0053 (0.004) |

0.0281* (0.013) |

0.0151* (0.007) |

0.0240* (0.011) |

| Outreach ($100 millions) | 0.0005 (0.001) |

0.0024 (0.004) |

0.0020† (0.001) |

0.0056* (0.003) |

| Noncitizens SNAP-eligible | −0.0058 (0.004) |

−0.0186 (0.013) |

−0.0061 (0.006) |

−0.0157 (0.012) |

| Governor is Democrat | 0.0037** (0.001) |

0.0154** (0.004) |

0.0057* (0.002) |

0.0084* (0.004) |

| SELECTED ELASTICITY CALCULATIONS FOR JOINT SNAP AND EITC/CTC PARTICIPATION | ||||

| State Unemployment | 0.334 | 0.346 | 0.390 | 0.314 |

| State % Full Year Worker | −0.772 | −0.101 | −0.635 | −0.283 |

| State % Part Year Worker | 0.125 | 0.288 | 0.145 | −0.110 |

| State % Not in Labor Force | −0.263 | −0.781 | −0.428 | −0.851 |

| State Median Wage | −1.371 | −1.042 | −1.613 | −1.263 |

| State Minimum Wage | 0.088 | 0.253 | −0.034 | 0.461 |

| EITC Subsidy Rate | 0.047 | 0.235 | 0.620 | 0.424 |

| State Has Refundable EITC | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.009 | 0.014 |

| Any Welfare Reform Waiver | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.008 |

| TANF Implementation | −0.133 | −0.103 | 0.018 | −0.028 |

| Max SNAP Benefit ($100s) | 0.872 | 0.457 | 0.235 | 0.567 |

| Observations | 176,072 | 39,596 | 80,574 | 27,522 |

| R-squared | 0.076 | 0.049 | 0.073 | 0.064 |

Standard errors in parenthesis control for heteroskedasticity and within-state autocorrelation. All models control for fixed state and time effects.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Elasticities are calculated at mean values by group for the selected policy variables.

Counterfactual Simulations: What Accounts for the post-2000 Growth?

In Tables 4–6 we return to the issue of whether or not changes in longer-term SNAP, EITC, and CTC participation since 2000—when dramatic spending increases in both programs begin to appear—are largely associated with cyclical and structural changes in the macroeconomy, in policy reforms, or in other factors aligned with changing demographics of the American family. We do so by conducting a series of counterfactual simulations based on the parameter estimates from the models in Tables 1 (for SNAP alone), 2 (for EITC and CTC alone), and 3 (for joint SNAP, EITC, and CTC). Specifically, we ask the following question: what would biennial participation in each program alone or in combination be if (i) state economic factors (unemployment rates, rates of full-time/part-time/not in labor force, median wages) had remained fixed at their 2000 values, (ii) if state and federal policies remained fixed at their 2000 values (state minimum wage, EITC subsidy, SNAP benefit, welfare and SNAP reforms), or (iii) if average demographics of the family remained fixed at their 2000 values. Each of the three experiments allow all other factors to change over the 2000–2012 period except for the set of variables being held constant at the 2000 values. We perform these simulations for each of the four samples. As a robustness check, Tables 7 and 8 then repeat the analysis for SNAP alone and joint SNAP and EITC/CTC, but instead use within-period parameter estimates; that is, the models and simulations both use data only from 2000–2012.17

Table 4.

Counterfactual Simulations of Changes in Biennial Participation in SNAP from 2000–2012, using 1980–2012 regressions

| All Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 104 | 37 | 70 | 35 | 71 | 90 | 15 |

| Low-Income Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 56 | 7 | 89 | 19 | 68 | 53 | 8 |

| Low-Education Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 110 | 55 | 54 | 51 | 56 | 51 | 36 |

| Single-Mother Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 38 | −23 | 154 | 9 | 79 | 53 | −19 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on parameter estimates in Table 1. Simulations hold identified variables fixed and allow others to vary over time. In each case, the year effects are allowed to vary over time. Shares do not sum to 100% since some factors are omitted.

Table 6.

Counterfactual Simulations of Changes in Biennial Participation in SNAP and EITC/CTC from 2000–2012, using 1980–2012 regressions

| All Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 104 | 89 | 23 | 6 | 94 | 90 | 9 |

| Low-Income Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 54 | 33 | 42 | −28 | 153 | 41 | 24 |

| Low-Education Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 107 | 63 | 43 | 7 | 93 | 51 | 39 |

| Single-Mother Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 38 | 33 | 23 | −66 | 272 | 48 | −11 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on parameter estimates in Table 3. Simulations hold identified variables fixed and allow others to vary over time. In each case, the year effects are allowed to vary over time. Shares do not sum to 100% since some factors are omitted.

Table 7.

Counterfactual Simulations of Changes in Biennial Participation in SNAP from 2000–2012, using 2000–2012 regressions

| All Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 104 | −16 | 113 | 52 | 56 | 99 | 1 |

| Low-Income Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 56 | 12 | 118 | 41 | 31 | 59 | −2 |

| Low-Education Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 110 | 32 | 78 | 92 | 21 | 62 | 26 |

| Single-Mother Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 38 | −55 | 260 | 18 | 53 | 51 | −20 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on parameter estimates in Appendix Table 5. Simulations hold identified variables fixed and allow others to vary over time. In each case, the year effects are allowed to vary over time. Shares do not sum to 100% since some factors are omitted.

Table 8.

Counterfactual Simulations of Changes in Biennial Participation in SNAP and EITC/CTC from 2000–2012, using 2000–2012 regressions

| All Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 104 | −79 | 163 | 11 | 90 | 84 | 15 |

| Low-Income Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 54 | −57 | 196 | −5 | 109 | 42 | 22 |

| Low-Education Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 107 | −63 | 151 | 51 | 54 | 45 | 45 |

| Single-Mother Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 38 | −108 | 344 | −51 | 229 | 40 | 5 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on parameter estimates in Appendix Table 6. Simulations hold identified variables fixed and allow others to vary over time. In each case, the year effects are allowed to vary over time. Shares do not sum to 100% since some factors are omitted.

In Table 4, from 2000 to 2012 biennial participation in SNAP among all families increased 104 %. If we fixed the state economic factors at their 2000 values, we would have predicted a 37 % increase in SNAP participation. This implies that changes in the state business cycle accounted for 70 % (≈ 100*(1-(37/104))) of the change over the biennial period (note that numbers in the table are rounded to the nearest whole number, and shares do not sum to 1 because some factors, e.g. year and state effects, are not reported). Policy changes are equally important, with a 71 % share, while demographics have a more modest role of 15 % (again recall shares do not necessarily sum to 100 % because of omitted factors). A similar pattern holds for low-income and low-skilled families, though for low-income families the economy is more important (89 %) than policy (68 %); for low-skilled families the economy-policy relationship is again evenly split, with 54 % of SNAP participation explained by changes in the economy, 56 % explained by policy, and a more substantive 36 % explained by demographics. Among single mother families, policy changes account for 79 % of the observed 38 % growth in biennial SNAP participation, but cyclical and structural labor market factors are associated with 154 % of the growth. Demographic shifts account for a negative share of the growth, meaning changes in the demographic composition of single-mother families alone actually slowed down the growth of longer-term SNAP participation.

In Table 5 we examine the predictors of biennial EITC and CTC participation alone based upon the parameter estimates in Table 2. In comparison with biennial SNAP participation, the EITC and CTC simulations illustrate that different groups exhibit unique responses. For the full sample, economic and demographic factors are equally important, and this roughly holds for low-skilled family heads. For the low-income sample, policy changes are the most important predictors of EITC and CTC participation. Less educated family heads are roughly evenly impacted by the economy, policy, and demographics. Families headed by a single mother are most sensitive to the economy as it relates to EITC and CTC use; had the economy remained at its 2000 level our models would have predicted 2 % growth in EITC and CTC, which instead emerged as a 9 % decline in forecasted participation.

Table 5.

Counterfactual Simulations of Changes in Biennial Participation in EITC/CTC from 2000–2012, using 1980–2012 regressions

| All Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 44 | 36 | 20 | 63 | −49 | 34 | 19 |

| Low-Income Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 13 | 11 | 16 | 6 | 54 | 4 | 68 |

| Low-Education Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| 67 | 48 | 26 | 79 | −28 | 36 | 35 |

| Single-Mother Families | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| State Labor Market Fixed at 2000 Levels | Policies Fixed at 2000 Levels | Demographics Fixed at 2000 Levels | ||||

| Actual Change (%) | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share | Predicted Change | Share |

| −9 | 2 | 119 | −13 | −49 | −5 | 42 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on parameter estimates in Table 2. Simulations hold identified variables fixed and allow others to vary over time. In each case, the year effects are allowed to vary over time. Shares do not sum to 100% since some factors are omitted.