Abstract

Gestational alcohol use is well documented as detrimental to both maternal and fetal health, producing increased offspring’s tendency for alcoholism, as well as behavioral and neuropsychological disorders. In both rodents and in humans, parental care can influence the development of offspring physiology and behavior. Animal studies that have investigated gestational alcohol use on parental care and/or their interaction mostly employ heavy alcohol use and single strains. This study aimed at investigating the effects of low gestational ethanol dose on parental behavior and its transgenerational transmission, with comparison between two rat strains. Pregnant Sprague Dawley (SD) and Long Evans (LE) progenitor dams (F0) received 1g/kg ethanol or water through gestational days 17– 20 via gavage, or remained untreated in their home cages. At maturity, F1 female offspring were mated with same strain and treatment males and were left undisturbed through gestation. Maternal behavior was scored in both generations during the first six postnatal days. Arched-back nursing (ABN) was categorized as: 1, when the dam demonstrated minimal kyphosis; 2, when the dam demonstrated moderate kyphosis; and 3, when the dam displayed maximal kyphosis. Overall, SD showed greater amounts of ABN than LE dams and spend more time in contact with their pups. In the F0 generation, water and ethanol gavage increased ABN1 and contact with pups in SD, behaviors which decreased in treated LE. For ABN2, ethanol-treated SD dams showed more ABN2 than water-treated dams, with no effect of treatment on LE animals. In the F1 generation, prenatal exposure affected retrieval. Transgenerational transmission of LG was observed only in the untreated LE group. Strain-specific differences in maternal behavior were also observed. This study provides evidence that gestational gavage can influence maternal behavior in a strain-specific manner. Our results also suggest that the experimental procedure during gestation and genetic variations between strains may play an important role in the behavioral effects of prenatal manipulations.

Keywords: Maternal care, Intragastric gavage, Rat, Transgenerational, Ethanol

1. Introduction

Alcohol is a widely consumed substance with significant health implications, and is particularly detrimental for mother and fetus when consumed during pregnancy. Regardless, epidemiological studies reveal that many women continue drinking during pregnancy despite the consequential increased risk of fetal alcohol syndrome, spectrum disorders, and tendency of alcohol use and abuse for the developing child in the future [1–3]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently stated that 7.6% of pregnant women self-reported alcohol use within the past 30 days, with 1.4% indulging in binge drinking at least once within the period [5]. Evidence of familial transmission of drinking behavior and alcoholism is well established in the literature. Genetic heritability of alcohol use disorders is around 50% in the general population [6]. Children born into families with greater alcohol use also show externalizing behavior problems, which are a risk factor for later alcoholism [7]. Interestingly, parental practices moderate these behavioral, cognitive, and psychological effects of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) and the familial predisposition to alcoholism in children [8] [9]. Parental warmth, consistency in discipline, and parental monitoring decrease the likelihood of behavioral problems in children with biological relatives consuming large quantities of alcohol [9]. This evidence demonstrates the importance of parental care in moderating the later-life consequences of predisposition to alcoholism.

Parental care is affected by exposure to environmental stressors. In humans, it has been suggested that the stress associated with poverty increases parental anxiety and irritability, thus influencing parent-child interactions [10]. In nonhuman primates, environmental adversity increases mother-infant conflicts [11]. In the California mouse, chronic intermittent stress reduces father contact with offspring [12]. The quality and quantity of maternal care is also reduced by chronic stress during gestation in the rat [13]. The prevalence of child abuse and its association with drug use and abuse is well established in the United States. In a 2003 report by the United States Office on Child Abuse and Neglect [14], one-third to two-thirds of child maltreatment cases were related to substance abuse. In fact, children whose parents abuse alcohol and other drugs were three times more likely to be abused and four times more likely to be neglected. Few human studies have looked at the effect of alcohol on human parental behavior, and their results lack consistency. Although Chassin et al. [15] and O’Connor et al. [16] found low-quality parenting in the presence of parental alcoholism, other studies have reported the opposite [17] or no effect [9] of alcohol on parental practices. Thus, there is a need for an improved understanding of the effect of alcohol use on parental behavior.

Animal models may provide much-needed insight. To date, animal models of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders have been widely used; however, few research groups have investigated gestational ethanol exposure effects on maternal behavior. Vorhees (1989) [18] used cross-fostering to study the influence of postnatal care on gestational ethanol exposure effects. They found no effect of prenatal ethanol on postnatal care in Long Evans (LE) rats following a liquid diet procedure where pregnant dams were exposed to ethanol throughout gestation. Marino et al. [19] looked at the effect of high doses (intragastric 4.5 g/kg) of ethanol during the entire gestation period on maternal care in LE rats. No effect on maternal behavior was found as a result of the prenatal exposure, although combined pre- and post- natal exposure was shown to increase pups’ ultrasonic vocalizations. The occurrence and latency of pup retrieval and nursing posture following low and moderate doses (1 and 2 g/kg, respectively) of ethanol exposure during late gestation were also investigated in Wistar-derived rats [20]. No effects were observed for these two behaviors. However, the maternal care observation period for this study was very short. Thus, more thorough investigation is needed to attest for the lack of effects of gestational ethanol exposure on the maternal behavior of this species. A third group investigated the combined effects of prenatal ethanol and nicotine on maternal behavior [21] and found slight, but significant, decreases in maternal care after this combined treatment. However the effects of nicotine or ethanol alone were not dissected. The present experiment aimed at investigating the effect of a low dose of ethanol exposure during late pregnancy in two strains of rats, the LE and the Sprague Dawley (SD), by performing a more comprehensive analysis of a wider array of behaviors indicative of maternal care.

Clarifying the influence of gestational alcohol exposure on maternal behavior is important, as quality of parental care has been shown to influence offspring development. In primates and rodents, maternal deprivation studies show behavioral and neurophysiological evidence that lack of appropriate maternal care results in increased anxiety and fearfulness [22–24], increased aggressive behavior [25], and impaired cognitive function in offspring [24] [26]. Even slight variations in maternal behavior may have an important impact on the psychological and physiological development of the young. Natural variations in maternal care in the rat are associated with differences in gene expression, in neurotransmitter and hormone release, and in behavior of the offspring [27–32]. The effects of maternal behavior on infant development persist to maturity and influence the offspring’s phenotype. More specifically, lower levels of maternal licking/grooming (LG) result in early onset of puberty [27, 28], increase stress reactivity [33], influence reproductive strategy [29, 31, 33, 34], and increase alcohol self-administration [35]. Furthermore, maternal behavior has been shown to be transmitted across generations through epigenetic modification, such that female rats that have received low level of maternal care will also provide low levels of maternal care to their offspring [36, 37] Thus, maternal care in the rodent has a large impact on the offspring outcome. Positive parenting practices can actually remedy some of the detrimental effects of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE), with improvements to both intelligence and coping skills in childhood [16, 38]. Additionally, variations in parenting style influence alcohol consumption and abuse in human adolescents and adults [39, 40]. Therefore, if alcohol consumption during pregnancy is capable of influencing maternal behavior, it will be important to determine whether variations in maternal care in the rodent mediate the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on offspring phenotype.

Although rat strains respond differently to similar experimental manipulations, few studies test multiple strains of rat to verify their results. Most researchers will spend their entire research career using the same strain, fearing that changing the animal model can change the effects they have previously found. Genetic variations between strains of rats may influence response to certain tests [41]. Additionally, rat strains have been shown to differ both in voluntary ethanol consumption [42] and in the effects of gestational stress on LG behavior [43]. For translational research purposes, it is vital to verify the validity of results, at least across different strains of the same species. Here we compare the effect of gestational ethanol and water, administered via gavage, on maternal behavior of both SD and LE rats.

An important aim of this study was to model gestational low-level alcohol consumption in humans and its consequences on fetal outcome. Exploring this aim using a rodent model required a paradigm that exposed pregnant dams to a small quantity of ethanol. Hence, we selected a PAE paradigm that has been proven to be effective, over the past two decades, to produce neurophysiological alterations that are similar to most paradigms that used longer durations of exposure to higher doses (42–44; Nizhnikov et al., submitted). Additionally, late gestation in the rat is a sensitive period during which perturbations may affect later maternal behavior [44]. During late gestation, the hypothalamic oxytocin system undergoes notable changes in preparation for parturition and nursing which are principally regulated by γ-aminobutyric acid and endogenous opioid systems, important targets for ethanol [45, 46]. Existing literature suggests that PAE may influence systems important for maternal care, such as oxytocin [47]. Thus, late gestation in the rodent may represent a critical window for the effects of ethanol exposure on future maternal behavior.

Research has shown that exposure to low-moderate doses of ethanol during late pregnancy in SD rats, results in an increase in ethanol consumption in offspring [48–50]. Considering that variations in maternal care may influence the offspring’s behavior, this experiment also aimed to investigate the effects of gestational ethanol exposure on maternal behavior in two strains of rat. Based on the research findings of Chassin and O’Connor [1, 15, 16], we predicted that gestational ethanol exposure would decrease levels of maternal behavior. Furthermore, since maternal care has been shown to be transmitted across generations [36], we also investigated the effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on maternal behavior in the adult female offspring, predicting that gestational exposure effects on maternal behavior would be passed on to future generations of mothers.

2. General Methods

2.1. Subjects

Thirty-four female Long-Evans (LE) rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA) and were allowed two weeks of acclimation in our colony prior to the beginning of the experiment. Twenty-eight adult female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats derived from animals obtained from Taconic (Germantown, NY, USA)) and born in our colony at Binghamton University were also used. These females were considered the first generation (F0). While the F0 animals differed in origin, all subsequent generations were born in our colony. Food and water for all animals were provided ad libitum. Animals were housed under controlled temperature (22 ± 1 C) conditions. No environmental enrichment or nesting material was provided. The day that pups were born was defined as postnatal day zero (PND 0). Dams were housed with their litters in a standard Plexiglas cage (22 × 23 × 45 cm) in the colony room. Weaning occurred at PND 21 when pups were pair-housed in same-sex, same-litter groups. Male breeders were housed in a separate holding room. At adulthood (70–90 days), F1 females (SD, n: 45; LE, n: 36) were randomly selected and allowed to mate with a non-related male of the same strain and treatment group. No more than 2 females and 1 male/litter were used. Since the pups produced from this study were later used in other experiments, animals were bred in 6 cohorts (3 for F1 and 3 for F2). Litters were left intact and undisturbed until PND 14, when offspring from F0 and F1 (2 cohorts) were counted and sexed. Litters with less than 5 pups were excluded from this study (F0: LE ethanol, n=1; SD water, n=1; F1: LE control, n=2; SD water, n=1). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines for laboratory animal use and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Binghamton University.

2.2. Mating

During mating, the room was maintained at a 12-12h light-dark cycle (with lights on at 0900). Two female (at least 70 days old) rats were housed in a Plexiglas mating cage (22 × 23 × 45 cm) with a single male for seven days, after which both females were transferred into a standard cage and pair-housed for another week. For Experiment 1, vaginal smears were collected (with 0.9% saline) daily during the seven-day mating period, and the day of sperm detection was considered gestation day zero (GD 0) as previously described [27]. Females were separated at the end of the second week and single housed in standard cages with wood shavings as bedding material and allowed to give birth. No environmental enrichment was provided to the animals in order to maintain the effects of the prenatal treatment.

2.3. Prenatal Treatment

During pregnancy, animals were housed on a 10–14 light-dark cycle, with lights on at 9 am. From GD 17 to 20, pregnant female rat progenitors (F0) received 1g/kg/day dose of ethanol (SD, n:11; LE, n:11) or the corresponding amount of vehicle (tap water; SD, n: 8; LE, n:10) via intragastric administration (gavage). This dose induces blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) in maternal blood, fetal blood, and amniotic fluid of approximately 50 mg/dl in the Wistar rat [51]. A third group remained undisturbed in their home cage during this period as an additional control for the gavage manipulation (control; SD, n: 9; LE, n: 13). The solution was delivered through a polyethylene cannula (PE 50) connected to a 10 cc syringe, and introduced into the stomach via the oral cavity. This procedure occurred between 1000 and 1100 hours daily and took about 15–20 seconds per rat. Rats in the untreated control group were left in their cages in the colony room during this period.

2.4. Maternal Behavior

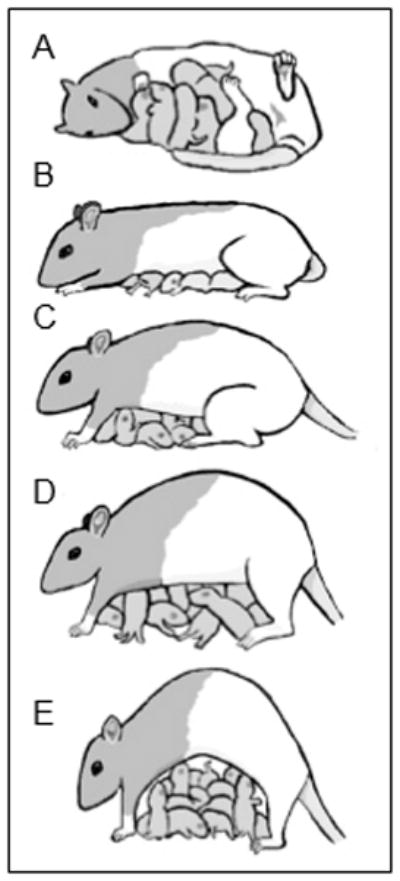

Maternal behaviors of lactating dams towards their pups were blindly scored by well-trained observers daily as initially described by Myers et al. 1989 [52] and adapted and regularly used in our laboratory [27–31]. Observations occurred three times in the light cycle (1030, 1300, and 1700 h) and twice during the dark cycle (0700 and 2000 h), during 75-minute observation periods for the first 6 postnatal days (PND 1 – PND 6). During an observation period, each litter was observed at approximately three minute intervals (for a total of 25 observations per period and 125 per day) for the following behaviors adapted from Myers et al. 1989 [52]: (1) maternal licking and grooming (LG) of pups, (2) nursing, (3) retrieving a pup to the nest, (4) being in contact with pups but not nursing, (5) being away from the pups. Nursing was recorded when pups were attached to the mother’s nipples and was scored as one of five postures: (1) passively (or supinely) nursing pups while laying on her side or back, (2) a blanket nursing posture, where the mother was over the litter but did not arch her back or extend her legs, and arch-back nursing (ABN), which was further divided into three categories; (3) ABN1, defined by the dam hovering over the litter, (4) ABN2, when the mother’s back was arched and her back or front legs were half-way extended (also termed kyphosis) [53], and (5) ABN3, when the mother’s back was arched and all her legs were completely extended so that the kyphosis was more pronounced (Figure 1). These nursing postures demand different amounts of energy from the mother; passive and blanket nursing require low energy expenditure, while ABN2 and ABN3 are more physically taxing. High arch-back nursing postures allow for more movement of the pups between nipples, which can be critical considering that a dam has only 12 nipples but can have up to 20 pups. It is important to note that while some of these behaviors are mutually exclusive (e.g. LG and away), some are not (e.g. LG and ABN), and such conditions were put into consideration throughout maternal observations and analysis.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of maternal nursing posture; A) passive; B) blanket; C) arch-back 1 (ABN1); D) arch-back 2 (ABN2); E) arch-back 3 (ABN3).

2.5. Intergenerational transmission

To investigate the effect of gestational ethanol exposure on the transmission of maternal behavior across generations, we compared the behavior of F0 dams that had F1 daughters used in this study.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to analyze maternal behavior over time (day). When interactions were found, the effect of strain was investigated by comparing the behavior of untreated LE and SD dams, and the effect of treatment was investigated by comparing the untreated, water-treated and ethanol-treated groups within each strain. When no effect of treatment was found in either strain, data were pooled within strain only. Cohort, litter (F1) and litter size were used as covariates. Paired-samples T tests were used to analyze change over days. Tukey’s HSD was used for post hoc tests. To reduce the risk of Type 1 error, significance for post hoc comparisons was set at p<.01 when the effect of time (day) was investigated. Correlation between mothers’ (F0) and daughters’ (F1) maternal behaviors were conducted with a two-tailed Pearson correlation. ANOVAs were used to compare litter size and sex ratio between the two generations. Levene’s F statistic for homogeneity of variance was used to analyze the range of litter size and sex ratio. Significance was set at the p<.05 level. When no effect of treatment was found, data were pooled in figures for the sake of clarity. All statistics were performed using SPSS (IBM, Version 21).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of gestational ethanol exposure

We investigated the effects of gavage of 1g/kg ethanol or water given daily between GD 17 and GD 20, in SD and LE dams (F0). Neither treatment nor strain difference had an effect on the number of pups per litter (12.8 ± 3.29) or on the male/female sex ratio (Table 1). Furthermore, we found no interaction of the behaviors investigated with either the cohort, litter size or male/female pup ratio (p>.8). We found important treatment effects and also interesting strain differences between SD and LE rats on dam’s maternal behavior.

Table 1.

Litter size and sex ratio (Mean and Range) of F0 generation Sprague Dawley and Long Evans ethanol, water and untreated control groups.

| Treatment group | Litter size (# pups) | Litter sex ratio (male/female) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | |

| SD Control (n:9) | 10.75 | 7–14 | 2.93 | 0.00–3.00 |

| SD Water (n:8) | 11.38 | 8–15 | 1.30 | 0.33–3.50 |

| SD Ethanol (n:11) | 11.00 | 8–18 | 1.45 | 0.50–3.00 |

| LE Control (n:13) | 10.50 | 5–18 | 1.17 | 0.50–1.67 |

| LE Water (n:10) | 10.00 | 5–15 | 1.31 | 0.30–2.33 |

| LE Ethanol (n:11) | 11.82 | 8–17 | 1.22 | 0.33–3.50 |

Note. SD = Sprague Dawley; LE = Long Evans

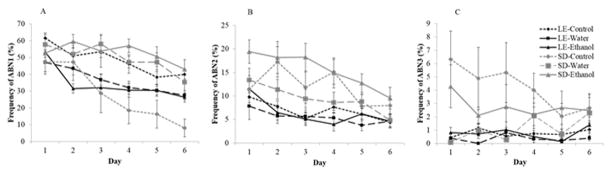

3.1.1 Nursing posture

We investigated the effects of both rat strain and drug treatment on animals’ maternal behavior by examining the average daily frequency of behavior during the first six days postpartum. We found that strain and treatment with ethanol or water gavage had significant effects on nursing behavior on both strains of rat. The frequency of ABN1 was found to decrease over time (F[5,280]=77.66, p<.001) (Fig. 2a). This nursing posture, which was favored the most by the lactating dams, also showed strain by treatment (F[2,56]=19.32, p<.001) and day by strain by treatment (F[10,280]=4.09, p<.001) interactions. When comparing the untreated groups, the frequency of ABN1 was found to be greater in SD compared to LE dams (F[1,20]=7.52, p<.05). We also found an effect of day, as the frequency of ABN1 was found to decline significantly over time (F[1,20]=11.35, p<.001) at Days 4 through 6 compared to Day 1 (p<0.01). This nursing posture also showed a main effect of treatment in the LE group (F[2,31]=8.34, p<.001), with untreated LE dams showing a greater frequency of ABN1 compared to water- and ethanol-treated animals (p<0.05). A significant effect of treatment was also found in the SD dams, although in the opposite direction to the effect seen in LE mothers, with water- and ethanol-treated dams showing a greater frequency of this behavior compared to untreated SD dams. In the SD strain we also found a day by treatment interaction (F[10,25]=2.54, p<.01), as the frequency of ABN1 declined steadily over time only in the untreated group.

Fig. 2.

Mean (± S.E.) percentage frequency of A) arch-back nursing 1 (ABN1), B) arch-back nursing 2 (ABN2), C) arch-back nursing 3 (ABN3) in the F0 generation of water-treated, ethanol-treated, and untreated Long Evans (LE) and Sprague Dawley (SD) dams over the first 6 days postpartum.

ABN2 frequency also showed a main effect of day (F[5,280]=21.04, p<.001), a strain by treatment interaction (F[2,56]=17.36, p<.001), and a day by stain by treatment interaction (F[10, 280]=2.09, p<.05) (Figure 2b). Untreated SD dams showed ABN2 more often than untreated LE dams, and this behavior was found to decline over time, as Day 6 frequency was significantly lower than Days 1, 2, and 4 (p<0.01). During this period, SD and LE ethanol-treated dams were significantly different, with LE ethanol-treated animals showing the lowest frequency of ABN2 and SD ethanol-treated dams showing the highest of the groups (p<.01). This behavior showed no effect of treatment in the LE dams. We found a main treatment effect (F[2,25]=4.45, p<.05) in the SD strain, with the ethanol-treated group displaying this behavior more frequently than SD water-treated dams (p<0.05).

ABN3 was the nursing posture demonstrated the least by the dams. However, we still were able to note a main effect of strain (F[1,56]=17.62, p<.001), with untreated SD dams displaying this posture more often than untreated LE mothers (Figure 2c). We also found a main effect of treatment (F[2,56]=4.2, p<.05), with control mothers showing this posture more often than water-treated dams. A trend for a strain by treatment interaction (F[2,56]=2.50, p=.09) was also noted. Post hoc analysis revealed that the control SD group had a greater frequency of ABN3 than the SD water-treated (p<.05). However, the SD control group was not significantly different from SD ethanol-treated dams for this behavior. We found no effect of treatment in the LE groups.

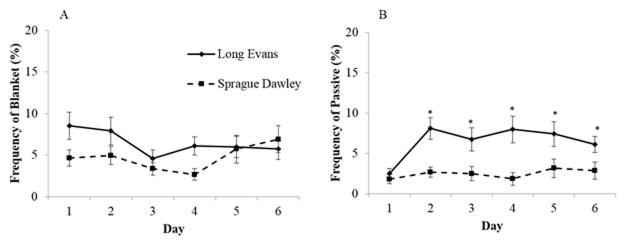

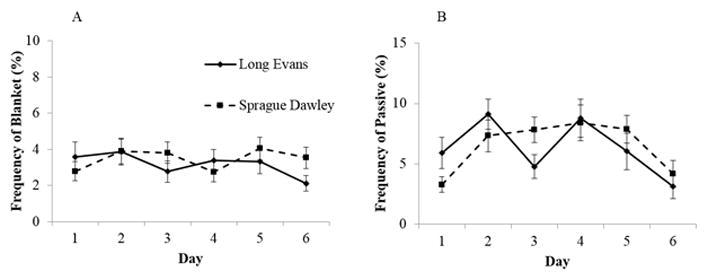

Blanket nursing posture frequency showed only a trend for change over time (F[5,280]=1.92, p=.09), and for effect of strain (F[2,56]=2.86, p=.1), but no effect of treatment or interaction was found (Figure 3A). Finally, we found an important main effect of strain in the frequency of passive nursing posture (Figure 3B). Starting at postpartum Day 2, LE rats displayed this posture significantly more than SD dams (p<.01). No effect of treatment, day or interaction was found for this behavior in the SD dams.

Fig. 3.

Mean (± S.E.) percentage frequency of A) blanket and B) passive nursing posture in water-treated, ethanol-treated, and untreated Long Evans (LE) and Sprague Dawley (SD) dams over the first 6 days postpartum. (p<.01)

3.1.2 Licking and grooming

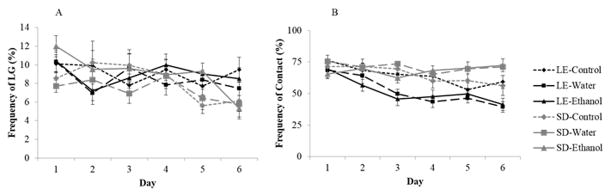

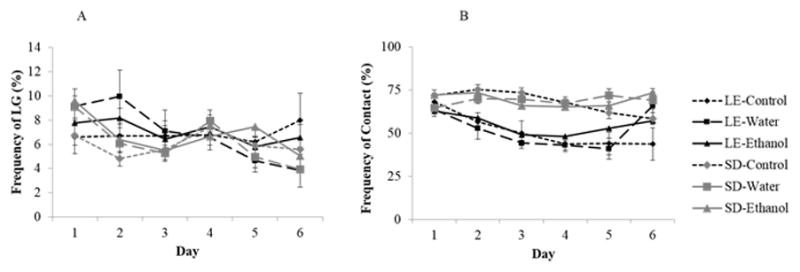

There was a main effect of day (F[5,280]=4.31, p<.001) and a trend for an interaction between day and strain (F[5,280]=2.21, p=.06) on the frequency of LG (Figure 4A). Post hoc testing revealed that LG frequency was stable across days in LE mothers, but declined over time in the SD dams. No differences in treatment or any other interaction was found for this behavior.

Fig. 4.

Mean (± S.E.) percentage frequency of A) licking and grooming (LG) and B) contact with the litter in the F0 generation of water-treated, ethanol-treated, and untreated (LE) and (SD) dams over the first 6 days postpartum.

3.1.3 Contact with pups and retrieval

There was a noted strain difference in the time dams spent in contact with their litter (F[1, 56]=18.37, p<.001) and a strain by treatment interaction (F[2,56]=4.34, p<.05) (Figure 4B). Indeed, SD mothers spent more time with their pups than LE mothers did. Furthermore, on average, SD ethanol- and water-treated dams were more frequently in contact with their litters than LE ethanol- and water-treated dams (p<.01). These results demonstrate that the gavage procedure had an opposing effect on the frequency of contact with the litter between the two strains of rat. We also found a main effect of day (F[5, 280]=10.61, p<.001), and a day by strain interaction (F[5, 280]=4.40, p<.01) which showed that although LE dams’ frequency of contact decreased with time, this effect was not found in SD dams (p<.01). However, when analyzing the time that untreated SD and LE dams spent in contact with their litter, we found a main effect of day (F[5, 20]=4.54, p<.001). Indeed, this behavior declined over time, as Day 1 frequency was significantly greater than Days 4 through 6 (p<.01). This effect was driven by the LE dams (F[1, 31]=37.03, p<.001), as the frequency of contact with pups declined over time, while it remained stable in the untreated SD dams. In the LE strain, we found a main treatment effect for this behavior (F[2,31]=3.94, p<.05), although a post hoc test revealed no significant difference between treatment groups.

We also scored the frequency of retrieving pups to the nesting area. This behavior was rarely observed. Only a trend for a treatment effect was noted (F[2,56]=2.61, p=.08), with a higher frequency of retrieval in control groups (0.21 ± 0.06%) compared to water- (0.11 ± 0.04%) and ethanol- (0.06 ± 0.1%) treated groups. No strain (LE: 1.92 ± 0.67%; SD: 0.89 ± 0.39%) or other effects were found for this behavior.

3.2 Effect of prenatal ethanol exposure

Prenatal ethanol and water exposure had no effect on the mean or range of litter size or sex ratio (Table 2). Furthermore, we found no interaction of the behaviors investigated with either the cohort, litter size or male/female pup ratio (p>.8). Unexpectedly, an ANOVA revealed an effect of generation (F[1, 112]=31.97, p<.001) on litter size, such that F1 dams (14.25 ± 0.37) had larger litters than F0 dams (10.92 ± 0.42). No other effects were found.

Table 2.

Litter size and sex ratio (Mean and Range) of F1 generation Sprague Dawley and Long Evans ethanol, water and untreated control groups.

| Treatment group | Litter size (# pups) | Litter sex ratio (male/female) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | |

| SD Control (n:15) | 13.75 | 8–20 | 1.04 | 0.54–1.50 |

| SD Water (n:16) | 13.23 | 10–16 | 1.38 | 0.40–4.00 |

| SD Ethanol (n:13) | 15.17 | 12–19 | 1.37 | 0.67–2.40 |

| LE Control (n:8) | 14.00 | 9–17 | 1.19 | 0.44–2.50 |

| LE Water (n:9) | 15.56 | 10–19 | 1.26 | 0.80–1.80 |

| LE Ethanol (n:19) | 14.24 | 10–20 | 1.16 | 0.31–2.40 |

Note. SD = Sprague Dawley; LE = Long Evans

Maternal behavior of lactating rats prenatally exposed to water, ethanol, or the home cage control condition was also observed in this experiment. In other words, these animals experienced ethanol in the womb but were not given any treatment while they were pregnant themselves. Prenatal treatment had fewer effects on the maternal behavior of dams than gestational exposure. However, strain differences in maternal behavior were again noted.

3.2.1. Nursing posture

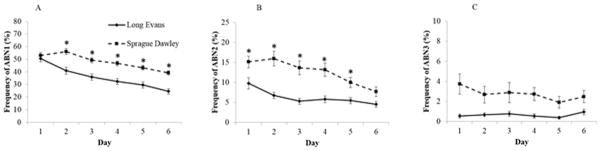

Like the F0 generation, ABN1 was also the nursing posture favored by the F1 generation dams. No effect of treatment was found to influence the display of this behavior in the F1 generation. Therefore, the data were thereafter pooled by strain. A repeated measures ANOVA indicated a main effect of strain (F[1, 75]=34.25, p<.001) on the frequency of ABN1 posture in the F1 generation (Figure 5A). On average, SD dams displayed this behavior more often than LE mothers. We also found an effect of day (F[5, 75]= 29.6, p<.001) and a day by strain interaction (F[5, 75]=3.15, p<.01). LE dams decreased the frequency of ABN1 starting at postpartum Day 2, while SD mothers did not show a decline in this behavior until Day 4 (p<.01).

Fig. 5.

Mean (± S.E.) percentage frequency of A) arch-back nursing 1 (ABN1), B) arch-back nursing 2 (ABN2), C) arch-back nursing 3 (ABN3) in F1 generation of Long Evans (LE) and Sprague Dawley (SD) dams over the first 6 days postpartum. (*p<.01)

We also found no effect of treatment on ABN2 in either SD or LE dams. However, we found a main effect of strain (F[1, 75]=14.37, p<.001) on the frequency of ABN2 in the F1 generation (Figure 5B). As in the frequency of ABN1, ABN2 was displayed more often in SD compared to LE mothers. There was also a significant main effect of day (F[5, 75]=6.18, p<.001) and a day by strain interaction (F[5, 75]=6.74, p<.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that the levels of ABN2 were significantly lower during Day 1 through 5 in LE dams compared to SD dams (p<.01). Furthermore, this behavior showed a sharp decline at postpartum Day 4 in SD mothers, whereas no change over time was observed in LE dams (p<.01). ABN3 was very rarely observed in the F1 generation and no significant difference was found between groups (Figure 5C).

No difference was seen in the display of blanket nursing posture frequency in the F1 generation (Figure 6A). Finally, no treatment or strain main effect was found in the frequency of passive nursing posture, but a significant main effect of day (F[5, 75]=5.96, p<.001) and a day by strain interaction (F[5, 75]=2.97, p<.05) were observed (Figure 6B). The frequency of this behavior was higher at Day 1, 2 and 4 in SD compared to LE dams (p<.01). No treatment effects were noted for any other nursing behaviors in this generation.

Fig. 6.

Mean (± S.E.) percentage frequency of A) blanket and B) passive nursing posture in the F1 generation of Long Evans (LE) and Sprague Dawley (SD) dams over the first 6 days postpartum.

3.2.2 Licking and grooming

The effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on LG frequency were also investigated (Figure 7A). No effect of treatment was found. However, a repeated measures ANOVA indicated a main effect of day (F[5, 75]=5.37, p<.001), and a day by strain interaction (F[5, 75]=2.29, p<.05). Indeed, as in the first generation, further analysis revealed that the frequency of LG declined over time in the SD dams (F[5, 41]=8.20, p<.001), but not in the LE dams for this generation.

Fig. 7.

Mean (± S.E.) percentage frequency of A) licking and grooming (LG) and B) contact with the litter in the F1 generation of Long Evans and Sprague Dawley dams over the first 6 days postpartum. (* p< .01)

3.2.3 Contact with pups and retrieval

We investigated the effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on the time dams spent with their litter. We found a significant main effect of strain (F[1, 75]=48.9, p<.001) demonstrating that F1 SD dams spent more time in contact with their litter compared to LE mothers, particularly between Days 2 to 5 (p<.01; Figure 7B). We also found a main effect of day (F[5, 75]=7.87, p<.001), and both a day by strain (F[5, 75]=4.5, p<.01) and day by treatment (F[10, 75]=1.93, p<.05) interactions. As we observed in the F0 generation, a decrease in contact with pups across days was observed, driven by the LE strain (F[5, 33]=7.90, p<.001), whereas SD dams’ frequency of this behavior was stable over time. Furthermore, the day by treatment interaction suggests that while control animals decrease their contact with their offspring through all six days, animals that received either water or ethanol have higher levels of pup contact on later days. Finally, at Day 6 gavage had opposite effects on the two strains, so that SD ethanol- and water-exposed dams were more often in contact with their litter than LE ethanol- and water-exposed mothers (p<.01).

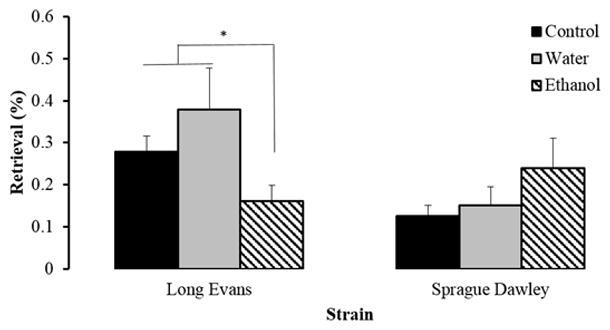

The frequency of retrieving pups to the nest area remained very low in this generation, as was observed in F0 dams. Nevertheless, we found a main effect of strain (F[1, 74]=5.16, p<.05) and a strain by treatment interaction F[2, 74]=4.94, p<.01) (Figure 8). In the untreated groups, LE dams retrieved their pups more frequently than SD mothers F[1, 21]=9.13, p<.01). Furthermore, we also found a main treatment effect in the LE strain F[2, 33]=4.29, p<.05), as ethanol-treated mothers retrieved their pups less often than untreated and water-treated LE dams. No effect of treatment was found in the SD strain for this behavior, which did not change over time.

Fig. 8.

Mean (± S.E.) percentage frequency of retrieval in the F1 generation of Long Evans (LE) and Sprague Dawley (SD) dams during the first 6 days postpartum. (*p<.05)

3.3. Intergenerational transmission

In LE lactating rats, individual variations in frequency of maternal behaviors have been shown to be transmitted from mothers to their female offspring, such that adult female offspring of High LG mothers also show high frequency of this behavior towards their own litter, while the opposite is true for Low LG female offspring [36, 37]. Pearson correlations were used to examine the effects of treatment during gestation on maternal care and the resulting effects on their female offspring’s own maternal behavior

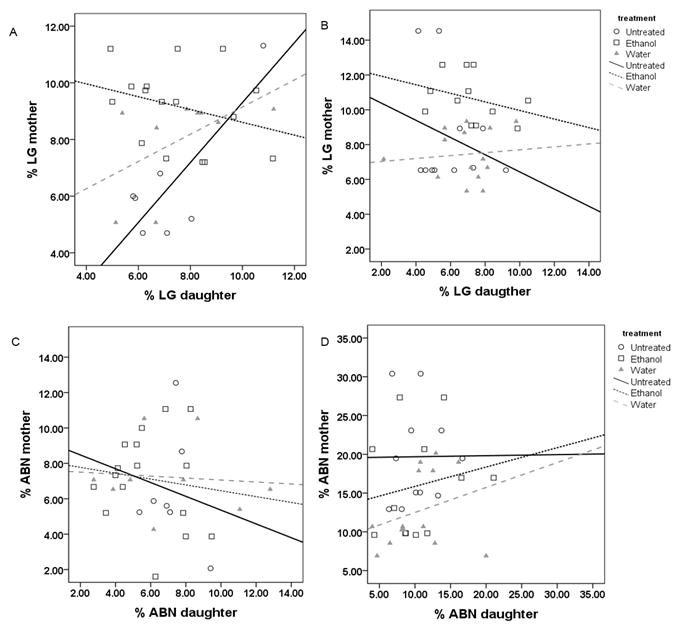

In the LE untreated group, LG was transmitted from mothers to female offspring (r=.81, n=7, p<0.05) (Fig 9A). This effect was lost in both the water-treated (r=.54, n=9, p=.13) and ethanol-treated (r=−.30, n=16, p=.26) groups. In the SD dams, no transmission of the LG behavior across generations was observed in any of the treatment groups (untreated: r=−.27, n=11, p=.45; water: r=.10, n=14, p=.72; ethanol: r=−.33, n=12, p=.30) (Fig 9B). High levels of ABN (ABN2 and ABN3) behavior were not transmitted across the two generations in any of the LE groups (untreated: r=.−.15, n=7, p=.71; water- r=−.09, n=9, p=.82; ethanol- (r=−.12, n=16, p=.65) (Fig. 9C). The transmission of high ABN behavior from mother to female offspring was also not observed in any of the SD treatment groups (untreated: r=.01, n=11, p=.98; water: r=.28, n=14, p=.32; ethanol: r=.18, n=12, p=.57) (Fig. 9D).

Fig. 9.

Scattergrams of (A,B) licking/grooming (LG) and (C,D) arch-back nursing posture (ABN2 and ABN3) of individual mothers and their adult offspring daughters toward their litters. (A) LG was transmitted from mother to female offspring in Long Evans (LE) untreated (r=.81, n=7 p<0.05) but not in water-treated (r=.54, n=9, p=.13) and ethanol-treated (r=−.30, n=16, p=.26) groups. (B) No correlation was found in LG frequency of Sprague Dawley (SD) dams (untreated: r=−.27, n=11, p=.45; water: r=.10, n=14, p=.72; ethanol: r=−.33, n=12, p=.30). (C) High levels of ABN were not correlated between mothers and daughters in LE animals (untreated: r=.−.15, n=7, p=.71; water: r=−.09, n=9, p=.82; ethanol: r=−.12, n=16, p=.65) or (D) SD (untreated: r=.01, n=11, p=.98; water: r=.28, n=14, p=.32; ethanol: r=.18, n=12, p=.57) treated groups.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the effects of gestational ethanol gavage on maternal behavior in two generations of two different strains of rat. Ethanol and water gavage during late pregnancy influenced the maternal behavior of both dams and their offspring once they became mothers. While there were very limited effects of the small dose of alcohol used in this experiment on behavior, the gavage procedure itself had an impact. Both the magnitude and direction of the effects were strain-specific. Here we demonstrated that SD and LE rats’ nursing behaviors were particularly sensitive to the effects of maternal gavage during pregnancy. Additionally, we uncovered effects on ABN and LG when we compared the prenatally exposed females to their mothers. While we did not find a direct effect of low-level gestational ethanol exposure on maternal behavior, these results demonstrate that the late gestational period is sensitive to laboratory manipulations in a strain-specific manner. Interestingly, we also discovered important strain differences in the display of most of the behaviors observed.

Both gestational stress and drug exposure are linked to changes in mother-offspring interactions [1, 13, 15, 16, 18]. Here we found that gestational exposures to ethanol and water through gavage during GD17-20 have similar effects on dams’ nursing behavior. Exposure to either treatment influenced the frequency and type of nursing posture mothers displayed during the first week postpartum. We believe that this finding may result from the stress associated with the gavage procedure, as has been shown previously [54, 55]. Stress may be particularly influential in this animal model since the period of exposure is short compared to other models [19, 56], which may reduce the capacity of animals to habituate to the manipulations. However, direct confirmation of changes in stress levels during or after gavage would be needed to confirm this hypothesis. Interestingly, gavage treatment had opposite effects on contact with pups and on ABN1 and ABN2 in the SD mothers compared to LE dams. Contact with pups was increased by treatment in both generation of SD dams and decreased in LE dams. In the first generation, SD rats showed an increase in the frequency of ABN1 after water or ethanol treatment. F0 SD dams exposed to ethanol displayed a higher frequency of ABN2 compared to LE ethanol-treated dams but also compared to SD water-treated animals. Additionally, F0 SD dams that had received water gavage during gestation increased the display of ABN3 compared to untreated animals. Marino et al. (2002) have also found that ABN is particularly sensitive to gestational ethanol exposure administered through gavage (19). While they have reported alterations to nursing behaviors in LE rats that more closely mirror our findings in the SD strain, it is important to note several major differences in methodology between their experiment and the current study. First, Marino et al. 2002 administered a larger dose (4.5g/kg) of ethanol to pregnant dams through the entire gestation period, and provided an additional 3.0g/kg of ethanol to pups from PND 2 through PND 10. The large dose of ethanol coupled with habituation to the gavage procedure may have blunted any physiological response to the method of ethanol administration. Additionally, dams were likely exposed to ethanol odors from their pups, which might have altered their maternal behaviors. Pups intoxicated with ethanol might also differently influence nursing behaviors, as this group reported an increase in ultrasonic vocalizations in ethanol-treated pups. The differences between our observations in SD and LE rats and Marino et al.’s (2002) findings further suggest that the ethanol dose required to produce behavioral effects may vary across strains.

The effects of the gavage procedure on maternal care may also be dependent on the timing of gestational exposure. Fernandez and colleagues (1983) found no difference in behaviors such as nursing or the amount of time spent in contact with pups between SD dams that were intubated twice daily with ethanol or sucrose solution during GD 10-14 or that were untreated controls [57]. However, it is possible that the lack of an effect of gavage on behavior in their experiment stems from the time period of exposure. As discussed previously, late gestation is a critical period for the onset of maternal behavior [45, 46]. An alternate explanation for the lack of behavioral effects seen by Fernandez et al. (1983) is their duration of behavioral observation, as they only observed maternal behavior during a single ten-minute period. A more detailed evaluation of maternal behavior might have yielded the effect of gavage that our results have indicated.

Each one of the maternal behaviors displayed by the dam has its own energy requirements and its own importance for offspring development. As rat pups cannot regulate their body temperature properly [58], contact with the mother during early life is very important for both warmth and nurturing. The quantity of energy required by the mother to maintain a nursing posture increases from passive and blanket to ABN1, 2 and 3. Upright crouching postures such as ABN1, 2 and 3 are necessary for milk ejection, with increased efficiency as the arching increases [59]. Passive nursing postures usually occur after a prolonged ABN, and are displayed more frequently as pups mature [60]. Unexpectedly, we discovered important strain differences in maternal behavior between SD and LE dams. Our results showed that although for both strains of rat ABN1 is displayed most frequently, SD dams also spend more time in ABN2 than LE mothers, while LE dams spend more time than SD mothers in passive posture. Furthermore, we also show that SD dams spend more time in contact with their litter compared to LE mothers. No difference was observed in the frequency of LG. This strain difference in nursing suggests lower energy expenditure for maternal behavior in LE compared to SD dams.

For most of the behaviors observed in the F0 generation, the results were replicated in the F1 generation. Interestingly, because of the lack of treatment effects, we were able to pool the data by strain in the F1 generation, increasing the power of the analysis, which revealed several differences from the F0 generation. Indeed, in the F1 generation, SD dams show a greater frequency of retrieval and time in contact with the litter, which was not observed in the first generation. Additionally, the analysis of F1 behaviors also revealed that a strain by day interaction for passive nursing posture during the first few observation days showed a greater frequency in SD dams compared to LE mothers. This was different from the finding seen in the F0 generation. Most importantly, in the F1 LE dams, ethanol-treated mothers showed a lower frequency of retrieval compared to untreated and water-treated dams. Thus, there were small but noticeable and unexpected differences in the behavior between the two generations.

Maternal behavior of our F1 adult female offspring was only weakly affected by their F0 mother’s ethanol or water treatment during pregnancy. Only the effects on retrieval in LE dams mentioned above were found in this generation. The effects of treatment became more obvious when a Pearson correlation compared dams’ behavior with that of their female offspring. Maternal behavior such as licking and grooming and high ABN postures (ABN2 and ABN3) have been shown to be transmitted across generations in the LE rat [36, 37]. In this study we were able to replicate the transmission of LG in the LE untreated controls, but not the transgenerational transmission of high ABN. The lack of transmission of ABN may be due to a lack of power in the analysis, since we only had seven mother-daughter dyads in that group. Maternal behaviors were not transmitted to female offspring when mothers had received water or ethanol gavage during gestation and, these behaviors were not transmitted across generations in either untreated or treated SD animals in both strains, LG in the ethanol-treated groups showed a moderate negative correlation. This suggests that the F1 daughter of a dam that received ethanol gavage displayed a frequency for this behavior opposite to the F0 generation. Thus, receiving ethanol during gestation compared to prenatally may have opposite effects on this behavior. Therefore, our data suggest that the maternal behavior of the SD and prenatally treated LE F1 dams was unlikely to be learned from their mothers. Although more evidence is needed, our results also suggest that transgenerational transmission of maternal care in rats may be strain-specific and affected by both gestational and prenatal manipulation.

In both humans and the rat, offspring can influence the parenting they receive. In fact, research suggests that ABN postures may be reflexive in nature, and may occur in response to ventral stimulation from pups [53]. With age, pups are increasingly capable of effectively stimulating the mother so she can maintain a high ABN posture (ABN2 and ABN3) favorable for milk ejection [59]. In humans, gestationally drug-exposed children induce higher levels of parental stress in both biological and foster parents [61], which has been shown to influence parental behavior [62]. Likewise, in rats, developmental exposure to ethanol alters pup-initiated nursing-related behaviors such as latency to attach to a nipple and ultrasonic vocalizations during nursing (19, see Kelly et al., 2009 for review). Finally, Fernandez et al. (1983) found that untreated control dams retrieved pups prenatally exposed to a high dose of ethanol (8g/kg per day) more frequently than untreated pups [57]. Therefore, it is important to consider the possibility that the changes in maternal care reported herein might stem from alterations in pup behavior or physiology. A cross-fostering analysis in future experiments would help delineate the source for our findings.

The difference found in the frequency of ABN posture between the two strains in the F0 generation suggests that pups may have been affected by the gavage their mothers received during pregnancy in a strain-specific manner. In SD animals, the increase in ABN1 in the ethanol and water gavaged dams and the decrease in ABN3 compared to untreated controls could result from less ventral stimulation from their pups. In contrast, the only change in nursing posture associated with gavage in LE dams was a decrease in ABN1, suggesting that the treatment had fewer effects on the mother-pup dyad. SD pups may be more sensitive to prenatal treatment than LE rats in terms of infant-dam interactions. Furthermore, ethanol and water gavage increased mother-pup contact in the SD strain and reduced it in the LE strain. Therefore, strain differences in pups’ influence on maternal behavior are a critical consideration needed when designing future studies.

Maternal behavior has been well described within the last decade in Wistar [34, 52] and in LE [36, 63] rats. These studies have provided tools to investigate natural variations in such behaviors in rodents. Timing and frequency of sampling are important factors for the assessment of maternal behavior in the rat [32, 36, 52]. The use of our experimental methodology has allowed for the discovery of marked differences in maternal behavior between SD and LE rats. SD dams spent more time in contact with their litter, and showed an increased frequency of ABN postures compared to LE dams. It would be interesting to investigate if these strain differences are driven by variations in pup behavior, and if these differences in maternal behavior influence other noted behavioral differences between these two strains as similarly reported in mice [64].

As previously reported by others in this species [32, 36], we found no effect of litter size on maternal behavior. However, it is important to mention that this finding is not consistent with studies in other rodents that have reported variations in parental investment associated with the number and sex ratio of offspring [65, 66]. Unexpectedly, we did find unexplainable differences in litter size between the F0 and F1 generations. Further investigation will be needed to clarify this finding.

There are some limitations associated with this experiment. First, a more effective translation of human alcohol consumption might have included intermittent ethanol exposure across gestation. However, as discussed above, we were particularly interested in late gestation in the rat, as this period is important for programming maternal behavior. Additionally, we hoped to minimize the handling-induced stress that accompanied the gavage procedure by limiting the number of treatments, although this may also have reduced habituation. Indeed, our current study has revealed effects of the gavage procedure itself on behavior. This study also did not investigate BAC in its subjects. While BAC data could have yielded helpful information as to any strain differences in ethanol metabolism, we wished to avoid the added stress of blood collection from our dams. Another limitation of this study is the difference in origin between strains of F0 animals. While the SD rats originated from our colony, F0 LE rats were purchased from a vendor. However, the LE animals were acclimated for two weeks prior to mating, thereby diminishing any potential residual stress from transportation. Finally, it is not possible to determine from the current study if our effects resulted from maternal behavior received, from genetic differences, from changes in pup behavior, or from in utero environment. A cross-fostering study would help provide insight as to the role of each of these factors.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we found few effects of gestational water and ethanol gavage on maternal care. Although in utero ethanol exposure has been shown to increase ethanol consumption in offspring [48–50], the increase in intake may not be influenced by maternal care received during the first week of life. Nevertheless, studies have shown that even very small variations in maternal care may influence the development of the offspring. Thus, the role of maternal behavior should be considered in future studies that investigate perinatal manipulations. Interestingly, we found strain-specific differences in maternal behavior. To our knowledge, this is the first paper in over twenty-five years to investigate strain differences in maternal behavior in the rat [52]. Our results suggest strain variations in sensitivity to experimental treatment that could have important implications for research. It is currently unknown if the effects we have found on maternal behavior stem from changes within the offspring. Finally, we found strain-specific transgenerational transmission of maternal care, which was altered by prenatal gavage treatment. The current experiment investigated two common strains of laboratory rat: the SD and the LE. Our findings emphasize the need to characterize the maternal behaviors in other strains of rat, and to determine their importance in offspring phenotype.

Highlights.

Ethanol and water gavage influence maternal behavior in a strain-specific manner.

Maternal behavior varies across strain of rat.

Transgenerational transmission of maternal behavior is strain-specific.

Prenatal gavage alters trangenerational transmission of maternal behavior.

References

- 1.O’Connor MJ, Whaley SE. Alcohol Use in Pregnant Low-Income Women. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(6):773–783. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alati R, et al. The developmental origin of adolescent alcohol use: Findings from the Mater University Study of Pregnancy and its outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98(1–2):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baer JS, et al. A 21-year longitudinal analysis of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on young adult drinking. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(4):377–385. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alcohol use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age - United States, 1991–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(19):529–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill SY, et al. Factors predicting the onset of adolescent drinking in families at high risk for developing alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(4):265–75. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuckit MA. Promoting Recovery in Alcohol-Dependent Patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(1):S5–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martel M, et al. Temperament Pathways to Childhood Disruptive Behavior and Adolescent Substance Abuse: Testing a Cascade Model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(3):363–373. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9269-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moos RH, Billings AG. Children of alcoholics during the recovery process: alcoholic and matched control families. Addict Behav. 1982;7(2):155–63. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molina BSG, Donovan JE, Belendiuk KA. Familial Loading for Alcoholism and Offspring Behavior: Mediating and Moderating Influences. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(11):1972–1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenblum LA, Andrews MW. Influences of environmental demand on maternal behavior and infant development. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1994;397:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris BN, et al. Chronic variable stress in fathers alters paternal and social behavior but not pup development in the biparental California mouse (Peromyscus californicus) Hormones and Behavior. 2013;64(5):799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champagne FA, Meaney MJ. Stress During gestation alters postpartum maternal care and the development of the offspring in a rodent model. Biol Psych. 2006;59(12):1227–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid J, Macchetto P, Foster S. No Safe Haven: Children of Substance-Abusing Parents. Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chassin L, et al. The relation of parent alcoholism to adolescent substance use: a longitudinal follow-up study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105(1):70–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor MJ, Kogan N, Findlay R. Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Attachment Behavior in Children. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26(10):1592–1602. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034665.79909.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latendresse SJ, et al. Parenting Mechanisms in Links Between Parents’ and Adolescents’ Alcohol Use Behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(2):322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vorhees CV. A fostering/crossfostering analysis of the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure in a liquid diet on offspring development and behavior in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1989;11(2):115–120. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(89)90049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marino MD, et al. Ultrasonic vocalizations and maternal–infant interactions in a rat model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Developmental Psychobiology. 2002;41(4):341–351. doi: 10.1002/dev.10077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pueta M, et al. Ethanol exposure during late gestation and nursing in the rat: Effects upon maternal care, ethanol metabolism and infantile milk intake. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2008;91(1):21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMurray MS, et al. Gestational ethanol and nicotine exposure: effects on maternal behavior, oxytocin, and offspring ethanol intake in the rat. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30(6):475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caldji C, Diorio J, Meaney MJ. Variations in maternal care alter GABA(A) receptor subunit expression in brain regions associated with fear. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(11):1950–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menard JL, Champagne DL, Meaney MJ. Variations of maternal care differentially influence ‘fear’ reactivity and regional patterns of cFos immunoreactivity in response to the shock-probe burying test. Neuroscience. 2004;129(2):297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Hasselt FN, et al. Individual variations in maternal care early in life correlate with later life decision-making and c-fos expression in prefrontal subregions of rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parent CI, Meaney MJ. The influence of natural variations in maternal care on play fighting in the rat. Dev Psychobiol. 2008;50(8):767–76. doi: 10.1002/dev.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ammerman RT, et al. Consequences of physical abuse and neglect in children. Clin. Clin Psychol Rev. 1986;6:291–310. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borrow AP, et al. Perinatal Testosterone Exposure and Maternal Care Effects on the Female Rat’s Development and Sexual Behaviour. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2013;25(6):528–536. doi: 10.1111/jne.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cameron NM, et al. Maternal Programming of Sexual Behavior and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Function in the Female Rat. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5):e2210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cameron NM, Fish EW, Meaney MJ. Maternal influences on the sexual behavior and reproductive success of the female rat. Hormones and Behavior. 2008;54(1):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cameron NM, Soehngen E, Meaney MJ. Variation in Maternal Care Influences Ventromedial Hypothalamus Activation in the Rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23(5):393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prior KM, Meaney MJ, Cameron NM. Variations in maternal care associated with differences in female rat reproductive behavior in a group-mating environment. Developmental Psychobiology. 2013;55(8):838–848. doi: 10.1002/dev.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peña CJ, et al. Effects of maternal care on the development of midbrain dopamine pathways and reward-directed behavior in female offspring. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;39(6):946–956. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cameron NM, et al. The programming of individual differences in defensive responses and reproductive strategies in the rat through variations in maternal care. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29(45):843–865. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uriarte N, et al. Effects of maternal care on the development, emotionality, and reproductive functions in male and female rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49(5):451–462. doi: 10.1002/dev.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Francis DD, Kuhar MJ. Frequency of maternal licking and grooming correlates negatively with vulnerability to cocaine and alcohol use in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2008;90(3):497–500. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Champagne FA, et al. Variation in maternal care in the rat as a mediating influence for the effects of environment on development. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:359–371. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Francis D, et al. Nongenomic Transmission Across Generations of Maternal Behavior and Stress Responses in the Rat. Science. 1999;286:1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson SW, et al. Maternal age, alcohol abuse history, and quality of parenting as moderators of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on 7.5-year intellectual function. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1732–1745. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145691.81233.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dube SR, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict Behav. 2002;27:713–725. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44:774–783. doi: 10.1080/00048674.2010.501759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smits BMG, et al. Genetic Variation in Coding Regions Between and Within Commonly Used Inbred Rat Strains. Genome Research. 2004;14(7):1285–1290. doi: 10.1101/gr.2155004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gauvin DV, Moore KR, Holloway FA. Do rat strain differences in ethanol consumption reflect differences in ethanol sensitivity or the preparedness to learn? Alcohol. 1993;10:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90051-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polytrev T, Weinstock M. Effects of gestational stress on maternal behavior in response to cage transfer and handling of pups in two strains of rat. Stress. 1999;3:85–95. doi: 10.3109/10253899909001114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenblatt JS, Siegel HI, Mayer AD. Progress in the Study of Maternal Behavior in the Rat: Hormonal, Nonhormonal, Sensory, and Developmental Aspects. In: Jay RAHCB, Rosenblatt S, Marie-Claire B, editors. Advances in the Study of Behavior. Academic Press; 1979. pp. 225–311. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wigger A, I, Neumann D. Endogenous opioid regulation of stress-induced oxytocin release within the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus is reversed in late pregnancy: a microdialysis study. Neuroscience. 2002;112(1):121–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russell JA, Brunton PJ. Neuroactive steroids attenuate oxytocin stress responses in late pregnancy. Neuroscience. 2006;138(3):879–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMurray MS, et al. Gestational ethanol and nicotine exposure: effects on maternal behavior, oxytocin, and offspring ethanol intake in the rat. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30(6):475–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diaz-Cenzano E, Chotro MG. Prenatal binge ethanol exposure on gestation days 19–20, but not on days 17–18, increases postnatal ethanol acceptance in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124(3):362–369. doi: 10.1037/a0019482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fabio MC, et al. Prenatal ethanol exposure increases ethanol intake and reduces C-fos expression in infralimbic cortex of adolescent rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2013;103(4):842–852. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nizhnikov ME, et al. Brief Prenatal Ethanol Exposure Alters Behavioral Sensitivity to the Kappa Opioid Receptor Agonist (U62,066E) and Antagonist (Nor-BNI) and Reduces Kappa Opioid Receptor Expression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014 doi: 10.1111/acer.12416. p. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Domınguez HD, et al. Perinatal Responsiveness to Alcohol’s Chemosensory Cues as a Function of Prenatal Alcohol Administration during Gestational Days 17–20 in the Rat. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 1996;65(2):103–112. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myers M, Brunelli S, Snair H. Relationships between maternal behavior of SHR and WKY dams and adult blood pressures of croos-fostered F1 pups. Dev Psychology. 1989;22(1):55–67. doi: 10.1002/dev.420220105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stern JM. Somatosensation and maternal care in Norway rats. In: Slater PJ, et al., editors. Advances in the study of parental behavior. New York: Academic Press: New York; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perkins A, et al. Alcohol exposure during development: Impact on the epigenome. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2013;31(6):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kelly S, Lawrence C. Intragastric Intubation of Alcohol During the Perinatal Period. In: Nagy L, editor. Alcohol. Humana Press; 2008. pp. 101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abel EL, Dintcheff BA. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth and development in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;207(3):916–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandez K, et al. Effects of prenatal alcohol on homing behavior, maternal responding and open-field activity in rats. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1983;5(3):351–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alberts JR. Huddling by rat pups: group behavioral mechanisms of temperature regulation and energy conservation. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1978;92(2):231–245. doi: 10.1037/h0077459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stern JM, Johnson Sk. Ventral somatosensory determinants of nursing behavior in Norway rats. I. Effects of variations in the quality and quantity of pup stimuli. Physiol Behav. 1990;47(5):993–1011. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90026-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stern JM, Levine S. Pituitary-adrenal activity in the postpartum rat in the absence of suckling stimulation. Hormones and Behavior. 1972;3:237–246. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(72)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelley SJ. Parenting stress and child maltreatment in drug-exposed children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16(3):317–328. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90042-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Potapova NV, Gartstein MA, Bridgett DJ. Paternal influences on infant temperament: effects of father internalizing problems, parenting-related stress, and temperament. Infant Behav Dev. 2014;37(1):105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Hasselt FN, et al. Adult hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor expression and dentate synaptic plasticity correlate with maternal care received by individuals early in life. Hippocampus. 2012;22(2):255–266. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caldji C, et al. Maternal behavior regulates benzodiazepine/GABAA receptor subunit expression in brain regions associated with fear in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(7):1344–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koskela E, et al. Maternal investment in relation to sex ratio and offspring number in a small mammal – a case for Trivers and Willard theory? Journal of Animal Ecology. 2009;78(5):1007–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clark MM, Galef BGJ. Unconfounded evidence of sex-biased, postnatal maternal effort by Mongolian gerbil dams. Dev Psychology. 1991;24(8):539–546. doi: 10.1002/dev.420240802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]