SUMMARY

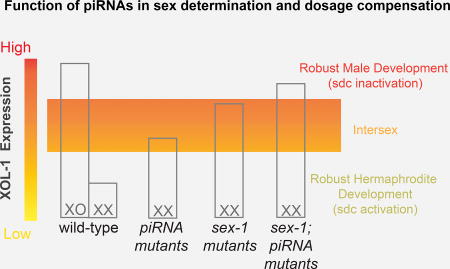

In metazoans, Piwi-related Argonaute proteins engage piRNAs (Piwi-interacting small RNAs) to defend the genome against invasive nucleic acids, such as transposable elements. Yet many organisms—including worms and humans—express thousands of piRNA that do not target transposons, suggesting that piRNA function extends beyond genome defense. Here we show that the X chromosome-derived piRNA 21ux-1 down-regulates XOL-1 (XO Lethal), a master regulator of X-chromosome dosage compensation and sex determination in C. elegans. Mutations in 21ux-1 and several Piwi-pathway components sensitize hermaphrodites to dosage compensation and sex-determination defects. We show that the piRNA pathway also targets xol-1 in C. briggsae, a nematode species related to C. elegans. Our findings reveal physiologically important piRNA–mRNA interactions, raising the possibility that piRNAs function broadly to ensure robust gene expression and germline development.

eTOC Blurb

Although piRNAs are known to defend the genome against transposons, it remains unclear whether they have additional functions beyond genome defense. Tang et al. show that an X chromosome-derived piRNA down-regulates XOL-1 expression to promote robust regulation of dosage compensation and sex determination in C. elegans.

INTRODUCTION

Piwi proteins and their piRNA co-factors silence transposons and promote fertility in diverse animals (Juliano et al., 2011; Siomi et al., 2011; Weick and Miska, 2014). The importance of transposon silencing for genome stability, and therefore fertility, seems obvious, but whether the role of piRNAs in fertility depends on transposon silencing alone remains a matter of debate. In worms, Piwi mutants show markedly reduced fertility that increases in severity over multiple generations—i.e., the mortal germline phenotype (Simon et al., 2014), but most piRNAs do not target transposons (Batista et al., 2008; Das et al., 2008; Ruby et al., 2006). Moreover, piRNAs can target with imperfect base-pairing (Bagijn et al., 2012; Goh et al., 2015; Gou et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2012), which dramatically increases their targeting potential. It seems reasonable therefore that transposon silencing is not the only way that piRNAs help ensure a fit germline and appropriate developmental outcomes.

Indeed, piRNA pathways have been linked to epigenetic programming, genome rearrangement, and developmental regulation in diverse organisms (Ross et al., 2014). For example, a Piwi-related Argonaute is required in the totipotent neoblast cells of planarians for the regeneration of body parts (Reddien et al., 2005). In ciliates, Piwi orthologs and parental piRNAs regulate DNA elimination during development of the new somatic macronucleus (Fang et al., 2012). The C. elegans Piwi protein, PRG-1, initiates heritable silencing of foreign genes, such as single-copy transgenes containing gfp sequences. Remarkably, PRG-1 is responsible for generating secondary small RNAs at a number of endogenous mRNAs (Ashe et al., 2012; Bagijn et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2012; Shirayama et al., 2012). The physiological relevance—if any—of this regulation has not been explored.

Here we show that a piRNA gene located on the X-chromosome, 21ux-1 (21U-RNA on the X chromosome), is complementary to sequences within the open-reading frame of the xol-1 mRNA and functions to repress xol-1 expression in the hermaphrodite germline. xol-1 encodes a GHMP (Galacto, Homoserine, Mevalonate and Phosphomevalonate) kinase homolog that specifies male(XO) development when active and hermaphrodite(XX) development when repressed (Luz et al., 2003; Miller et al., 1988; Rhind et al., 1995). Consistent with the idea that 21ux-1 promotes robust regulation of xol-1, we show that 21ux-1 mutations dramatically enhance the dosage compensation and sexual transformation phenotypes of animals with mutations in sex-1 or sdc-2. Moreover, these synergistic phenotypes are strongly suppressed upon loss of xol-1. We show 21ux-1 acts maternally to ensure the robust sensitivity of zygotes to the dose of X-signal elements. Furthermore, we show that the piRNA pathway regulates the expression of the xol-1 ortholog in C. briggsae, a related nematode that separated from C. elegans 50–100 million years ago. Together, our findings provide evidence that piRNA-mediated mRNA surveillance has physiological consequences for the proper regulation of embryonic development across Caenorhabditis species.

RESULTS

21ux-1 targets xol-1 and represses its expression

The X chromosome-derived piRNA locus 21ux-1 produces the single most abundant piRNA, yet its function is unknown (Gu et al., 2012). piRNA targeting recruits RdRP (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) to generate secondary small RNAs termed 22G-RNAs that guide silencing by members of an expanded group of WAGOs (Worm Argonautes) (Bagijn et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2012). A parallel study (Seth et al., co-submitted), reprogrammed the 21ux-1 locus to target gfp, i.e., 21ux-1(anti-gfp) using CRISPR/CAS9 genome editing. To identify candidate targets for 21ux-1 piRNA, we examined this 21ux-1(anti-gfp) strain for endogenous genes whose levels of PRG-1-dependent 22G-RNAs were reduced. This analysis revealed sixteen genes, including the well-studied gene xol-1 (Figures 1A and S1A). These findings were confirmed in our analysis of a second 21ux-1 allele that completely deletes the 21ux-1 piRNA, 21ux-1(deletion) (Figure 1A). A search of the xol-1 mRNA revealed a putative 21ux-1 target site that could base-pair perfectly with positions 2 to 15 of the piRNA (Figure 1A).

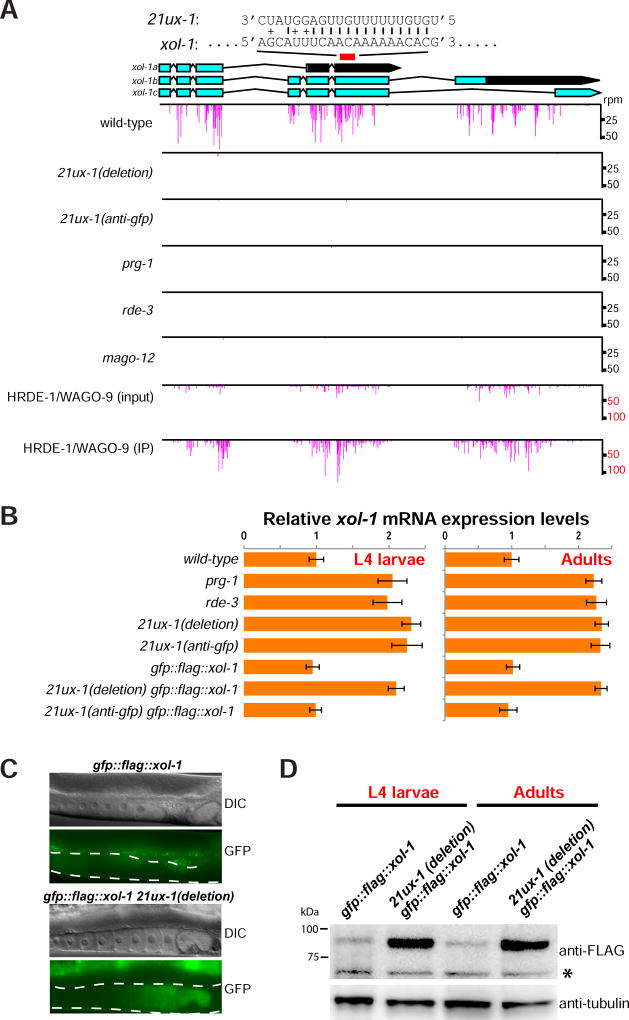

Figure 1. 21UX-1 targets the xol-1 transcript, induces 22G-RNA production, and represses xol-1 expression.

(A) 21ux-1 and 22G-RNAs targeting xol-1 mRNA in wild-type, 21ux-1(deletion), 21ux-1(anti-gfp), prg-1, rde-3, mago-12 mutants, and in HRDE-1/WAGO-9 input and IP samples are illustrated graphically. Histograms represent the position of 5’ end of 22G-RNAs at xol-1 locus. The position and base-pairing interaction between 21ux-1 and xol-1 are indicated above the genome browser view. I marks A:U or G:C base pairs. + marks G:U wobble base pairs.

(B) qRT-PCR of xol-1 mRNA from total RNAs isolated from synchronized populations at late L4 larvae and Adult stages. Expression of actin mRNA (act-3) served as the internal control. Data were collected from three independent biological replicates. Error bars represent Standard Deviation.

(C) Representative Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) image and fluorescence micrographs showing GFP::FLAG::XOL-1 expression (green) from wild-type and 21ux-1(deletion) animals. The dashed lines outline the position of the germline. Bright signals detected outside of the germline are from autofluorescence of gut granules.

(D) Western blotting analysis of proteins isolated from gfp::flag::xol-1 and 21ux-1(deletion) gfp::flag::xol-1 strains at late L4 larvae and Adult stages. The anti-FLAG antibody (top) detecting GFP::FLAG::XOL-1 and anti-tubulin antibody (bottom) were used. An asterisk marks a non-specific band.

Based on published deep-sequencing data we deduced that the xol-1-targeted 22G-RNAs are dependent on both the PRG-1 and WAGO pathways. For example, mutations that disrupt these pathways including prg-1 (Piwi), rde-3 (putative polynucleotide polymerase required for 22G-RNA accumulation) (Chen et al., 2005), and the 12 wago genes (mago-12) (Gu et al., 2009; Yigit et al., 2006), led to significant reduction of xol-1 22G-RNAs. Moreover, these 22G-RNAs were enriched in the HRDE-1/WAGO-9 immunoprecipitation (Figure 1A; Buckley et al., 2012; Shirayama et al., 2012).

Because the PRG-1 and WAGO pathways typically silence their targets (Ashe et al., 2012; Bagijn et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2012; Shirayama et al., 2012), we measured xol-1 mRNA levels in mutants that disrupt these pathways. In 21ux-1, prg-1, and rde-3 mutants, xol-1 mRNA levels were increased by 2- to 3-fold (Figure 1B). Developmental analysis of these mutants revealed that xol-1 mRNA levels were elevated by the L4 larval stage (before embryos are formed) and persisted throughout adulthood in hermaphrodites (Figure 1B). Thus, 21ux-1 along with piRNA pathway components appears to repress xol-1 mRNA expression in the L4 and adult germline.

To examine XOL-1 protein expression, we engineered the xol-1 locus to express a GFP::FLAG::XOL-1 fusion protein. In an otherwise wild-type background, gfp::flag::xol-1 hermaphrodites rarely produce male offspring, and we did not observe GFP fluorescence in embryos (Figure 1C; Data not shown). In a him-8 (high incidence of males) background, gfp::flag::xol-1 hermaphrodites produced male progeny at the expected frequency (~40%; Figure S1B) (Phillips et al., 2005), indicating that the GFP::FLAG::XOL-1 fusion protein is functional. Moreover, GFP fluorescence was readily detected in some embryos (Figure S1C), as expected for XO-specific expression of XOL-1 (Rhind et al., 1995).

In 21ux-1(deletion) hermaphrodites, GFP fluorescence was detected in the oocytes and in early embryo (Figure 1C), and gfp::flag::xol-1 mRNA was derepressed (Figure 1B). Furthermore, GFP::FLAG::XOL-1 fusion protein levels as measured by western blotting were significantly increased at both the L4 and adult stages (Figure 1D). The re-specified 21ux-1(anti-gfp), which can silence a GFP transgene (Seth et al., co-submitted), was sufficient to silence gfp::flag::xol-1 expression (Figures 1B–D). Together, these data indicate that a single piRNA, 21ux-1, directly regulates xol-1 mRNA and protein expression in the hermaphrodite germline.

21ux-1 promotes dosage compensation and sex-determination

xol-1 negatively regulates the activity of the hermaphrodite-specific sdc (sex determination and dosage compensation) genes (Dawes et al., 1999; Strome et al., 2014). Activation of xol-1 is thus essential for male development, but dispensable for hermaphrodite development (Miller et al., 1988; Rhind et al., 1995). Hermaphrodites with abnormally elevated xol-1 expression exhibit a range of phenotypes that include embryonic and larval death, partial sexual transformation (psuedomale formation), abnormal shortened body morphology (dumpy), and vulval and egg-laying defects (Carmi et al., 1998; Miller et al., 1988; Rhind et al., 1995). Although XOL-1 expression was increased in 21ux-1 and piRNA pathway mutants, these single mutants showed at most a mild reduction in hermaphrodite viability (Figure 2A and Table 1).

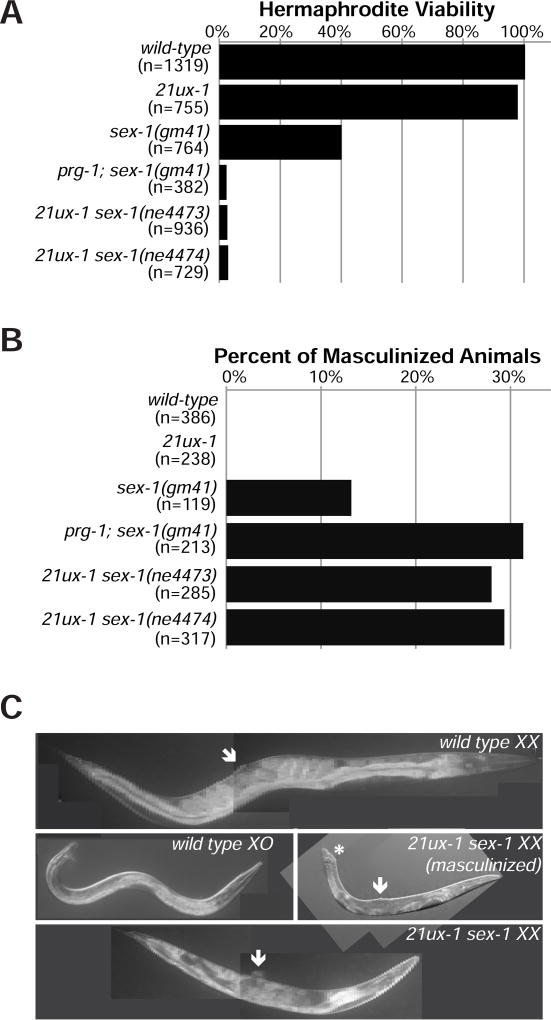

Figure 2. 21ux-1 acts with sex-1 to regulate dosage compensation and sex determination.

(A and B) Percentage of XX viability and masculinized XX animals in wild-type, 21ux-1(anti-gfp), sex-1(gm41), prg-1; sex-1(gm41), 21ux-1(anti-gfp) sex-1(ne4473) and 21ux-1(anti-gfp) sex-1(ne4474) mutant strains. n. Total number of animal scored.

(C) Representative DIC imaging of wild-type XX, 21ux-1 sex-1 XX, wild-type XO and surviving 21ux-1 sex-1 masculinized XX animals. An asterisk marks a masculinized tail. Arrows mark the vulva.

Table 1.

The piRNA pathway functions in sex determination and dosage compensation.

| Genotype | Hermaphrodite viability (%) (Number of Animal Scored) |

Phenotype of Survivors |

|---|---|---|

| wild-type | 100.4% (1319) | Wild-type |

| 21ux-1(anti-gfp) | 98.0% (755) | Slightly Tra |

| prg-1(tm872) | 92.6% (894) | Reduced fertility |

| rde-3(ne3370) | 78.5% (503) | Reduced fertility |

| sex-1(gm41) | 40.1% (764) | Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| 21ux-1(anti-gfp) sex-1(ne4473) | 2.6% (936) | Very Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| 21ux-1(anti-gfp) sex-1(ne4474) | 2.9% (729) | Very Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| prg-1(tm872); sex-1(gm41) | 2.4% (382) | Very Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| rde-3(ne3370); sex-1(gm41) | 1.4% (147) | Dpy; Tra; Egl; Sterile |

| sex-1(RNAi) | 50.9% (601) | Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| prg-1(tm872); sex-1(RNAi) | 3.2% (755) | Very Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| 21ux-1(anti-gfp) sex-1(RNAi) | 5.9% (768) | Very Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| 21ux-1(deletion) sex-1(RNAi) | 6.5% (417) | Very Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| 21ux-1(anti-gfp) sex-1 (RNAi) gfp::flag::xol-1 | 52.9% (223) | Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| 21ux-1(deletion) sex-1 (RNAi) gfp::flag::xol-1 | 6.2% (350) | Very Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| sdc-2(RNAi) | 78.3% (811) | Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| 21ux-1(deletion) sdc-2(RNAi) | 18.1% (341) | Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| 21ux-1(anti-gfp) sdc-2(RNAi) | 15.8% (939) | Dpy; Tra; Egl |

| sex-1(gm41); sdc-2(RNAi) | 1.3% (682) | Very Dpy; Tra; Egl |

Hermaphrodite viability and phenotype of survivors were scored. RNAi experiments were carried out by feeding worms bacteria expressing dsRNA. Dpy: Dumpy. Tra: Transformer. Egl: Egg-laying defective.

X-signal elements (XSEs) that count the X-chromosome-to-autosome ratio and repress xol-1 are partially redundant, and mutations in multiple XSEs are required to fully activate xol-1 (Carmi et al., 1998; Farboud et al., 2013; Gladden and Meyer, 2007; Hodgkin et al., 1994; Nicoll et al., 1997; Skipper et al., 1999). We therefore tested whether the piRNA pathway acts redundantly with XSEs to repress xol-1 expression. The nuclear hormone receptor SEX-1, for example, directly binds to the xol-1 promoter and represses xol-1 transcription (Carmi et al., 1998; Farboud et al., 2013). As previously reported (Carmi et al., 1998), depleting sex-1 via RNA interference (RNAi) or loss-of-function mutations reduced hermaphrodite viability by 50% to 60% (Figure 2A and Table 1), with survivors showing dumpy, egg-laying defective, and masculinized phenotypes (Table 1). Strikingly, simultaneous depletion of sex-1 in prg-1, rde-3, or 21ux-1 mutants led to nearly 100% lethality in hermaphrodites (Figure 2A and Table 1). Moreover, the XX survivors showed strong sexual transformations, including male-like tail morphogenesis, and became very dumpy (Figures 2B and 2C). The 21ux-1(deletion) and 21ux-1(anti-gfp) alleles exhibited identical synthetic phenotypes when combined with sex-1, in the context of a wild-type xol-1 locus (Table 1).

Since 21ux-1 targets mRNAs other than xol-1, the synthetic phenotypes we observed could result from misregulation of one or more of these other targets. We showed above that the re-specified 21ux-1(anti-gfp) piRNA can repress the gfp::flag::xol-1 allele, but it should not repress other 21ux-1 targets. In the presence of endogenous xol-1, sex-1(RNAi) is synthetic lethal with both 21ux-1(deletion) and 21ux-1(anti-gfp) alleles. In the gfp::flag::xol-1 background, however, sex-1(RNAi) was still strongly synthetic lethal with the 21ux-1(deletion) but was no longer synthetic lethal with 21ux-1(anti-gfp) (Table 1). Thus, 21ux-1(anti-gfp) mediates functional repression of gfp::flag::xol-1 by targeting the gfp sequences of the fusion gene. These findings confirm that piRNA mediated regulation of xol-1 function is important for robust dosage compensation and sex determination.

The above findings suggest that 21ux-1 and sex-1 repress xol-1 expression independently, or in parallel. Consistent with this idea, we found that xol-1 loss-of-function mutations partially rescued the viability of 21ux-1 sex-1 double mutant animals (Table 2). The degree of rescue was comparable to the levels observed in previously described xol-1 sex-1 double mutant strains (Gladden et al., 2007).

Table 2.

21ux-1 acts upstream of xol-1.

| Genotype | Hermaphrodite viability (%) (Number of Animal Scored) |

|---|---|

| xol-1(y9) | 96.0% (1001) |

| xol-1(ne4472) | 94.6% (835) |

| 21ux-1 sex-1(ne4473)# | 2.6% (936) |

| 21ux-1 sex-1(ne4474)# | 2.9% (729) |

| 21ux-1 xol-1(ne4475) sex-1(ne4476) | 72.1% (970) |

| 21ux-1 xol-1(ne4475) sex-1(ne4477) | 75.8% (959) |

| sdc-2(RNAi) | 77.5% (614) |

| xol-1(y9) sdc-2(RNAi) | 94.3% (703) |

| 21ux-1 sdc-2(RNAi) | 15.2% (487) |

| 21ux-1 xol-1(ne4475) sdc-2(RNAi) | 91.2% (591) |

Viability of progeny from mutant animals was calculated.

The same dataset from Table 1.

To further explore the relationship between 21ux-1 and xol-1 expression, we examined XX lethality in combination with sdc-2 depletion. XOL-1 down-regulates dosage compensation genes, such as sdc-2 (Dawes et al., 1999). Hermaphrodites with a complete loss of sdc-2 function are inviable (Dawes et al., 1999; Gladden et al., 2007). However, RNAi-mediated depletion of sdc-2 caused an intermediate phenotype, reducing XX viability to ~78% (Table 1), which allowed us to explore potential synthetic interactions between sdc-2(RNAi) and 21ux-1. As previously shown (Gladden et al., 2007), we found that sdc-2(RNAi) in a sex-1 null mutant results in a near complete loss of hermaphrodite viability (to ~1%, Table 1). Similarly, sdc-2(RNAi) in 21ux-1 mutants caused a marked loss of viability (to ~18%, Table 1). For both double mutants, the survivors showed a high incidence of sexual-transformation and body morphological defects (Table 1). If 21ux-1 functions through xol-1, then mutations in xol-1 should suppress the synergistic lethality caused by the combination of 21ux-1 and sdc-2 (RNAi). Indeed, loss of xol-1 activity strongly suppressed the synthetic lethality caused by loss of both 21ux-1 and sdc-2(RNAi) (Table 2). Together these findings suggest 21ux-1 acts directly on xol-1 to regulate dosage compensation and sex determination.

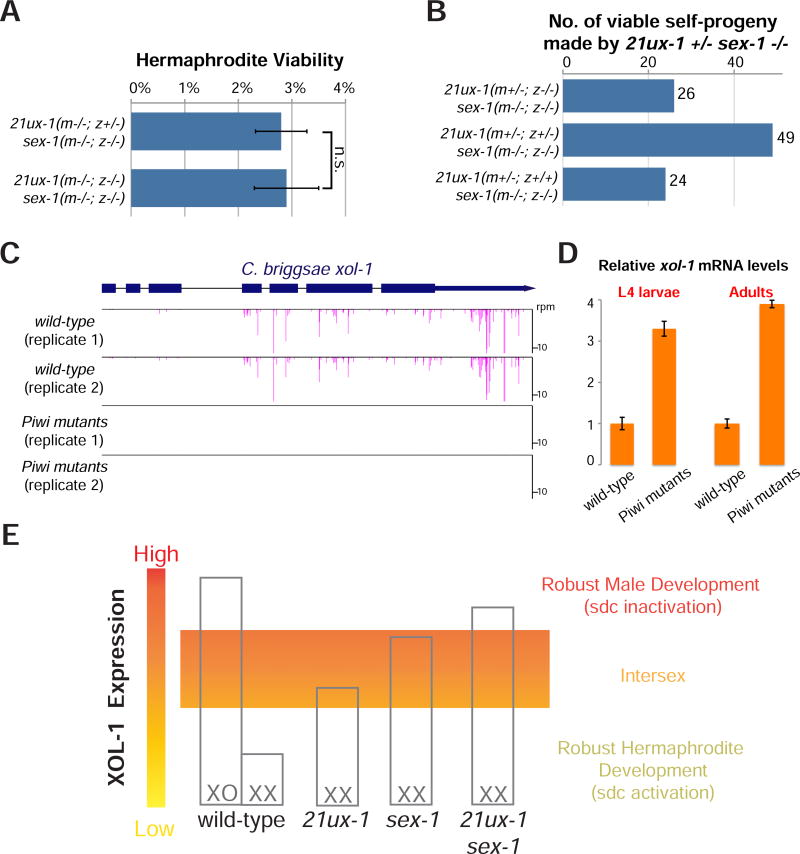

21ux-1 has a maternal effect

PRG-1 and piRNAs are expressed in the maternal and paternal germlines (Batista et al., 2008; Das et al., 2008; Wang and Reinke, 2008), while xol-1 levels are thought to be regulated in response to X-signal elements in the early embryo. We therefore explored the parental and zygotic roles of 21ux-1 expression in dosage compensation and sex determination. Mating sex-1 single-mutant males to homozygous 21ux-1 sex-1 double-mutant hermaphrodites failed to rescue the viability of the resulting 21ux-1/+ sex-1 hermaphrodite progeny, indicating that paternal and zygotic expression of 21ux-1 are insufficient to rescue viability (Figures 3A and S2). Conversely, hermaphrodites homozygous for sex-1 and heterozygous for 21ux-1 (21ux-1/+ sex-1−/−) produced viable 21ux-1−/− self-progeny at the same frequency as 21ux-1+/+ self-progeny (Figures 3B and S2). Thus, maternal expression of 21ux-1 is necessary and sufficient for the viability of homozygous 21ux-1 sex-1 progeny.

Figure 3. Maternal expression of 21ux-1 contributes to dosage compensation and sexual development and piRNAs regulate xol-1 expression in C. briggsae.

(A) Viability of 21ux-1(m−/−; z−/+) sex-1 (m−/−; z−/−) was calculated as the ratio of viable hermaphrodites to viable males as equal numbers of males and hermaphrodites are expected. Viability of 21ux-1(m−/−; z−/−) sex-1 (m−/−; z−/−) was calculated as the ratio of viable adults to the total number of embryos. The genetic crosses are illustrated in Figure S2. Data were collected from four independent crosses. Error bars represent Standard Deviation. m, maternal expression; z: zygotic expression. Data were collected from three independent experiments. Error bars represent Standard Deviation. n.s. Not Significant.

(B) Number of 21ux-1(m+/−; z−/−) sex-1(m−/−; z−/−), 21ux-1(m+/−; z+/−) sex-1(m−/−; z−/–), and 21ux-1(m+/−; z+/+) sex-1(m−/−; z−/−) progeny produced from 21ux-1+/− sex-1−/− hermaphrodites detected by sequence-based genotyping. The genetic crosses are illustrated in Figure S2.

(C) 22G-RNAs mapped to xol-1 locus in isogenic C. briggsae wild-type and Piwi mutant strains are illustrated. The histograms show the position and relative abundance of 22G-RNAs.

(D) Relative xol-1 mRNA level at L4 larvae and Adult stages as measured by qRT-PCR. Expression of actin mRNA (act-5) served as the internal control. Data were collected from six independent biological replicates. Error bars represent Standard Deviation.

(E) Model illustrating the function of 21ux-1 and sex-1 in regulating xol-1 expression and promoting robust dosage compensation and sex determination in C. elegans.

Finally, we mated wild-type males to homozygous 21ux-1 sex-1 hermaphrodites to generate hemizygous 21ux-1 sex-1 male and heterozygous 21ux-1/+ sex-1/+ hermaphrodite progeny. As expected, we found that sex-1 and 21ux-1 activities were not essential for male viability or development (Figure S3A). By contrast, we observed a partial rescue among the XX progeny from this cross presumably due to zygotic expression of sex-1, but we observed significantly fewer viable (21ux-1/+ sex-1/+) XX progeny relative to XO progeny (Figure S3B). This latter result suggests that both 21ux-1 and sex-1 may contribute maternally to the viability of hermaphrodite progeny, or that the reduction in maternal 21ux-1 uncovers a zygotic haploinsufficiency for sex-1. Consistent with the former possibility, a previous report has shown that SEX-1 activity is contributed in part maternally (Carmi et al., 1998; Gladden et al., 2007). Taken together, these findings suggest that 21ux-1 is required maternally for robust xol-1 regulation and for the proper development of hermaphrodite progeny.

piRNA regulation of xol-1 is conserved in the related nematode C. briggsae

We wished to study if piRNAs have conserved functions in regulating dosage compensation and sex determination in other Caenorhabditis species. C. briggsae is an ideal model for this comparative study as its whole genome is sequenced and well annotated (Stein et al., 2003). C. briggsae and C. elegans are thought to have separated from a common ancestor 50~100 million years ago (Coghlan and Wolfe, 2002). Both species have the same chromosome numbers, similar genome sizes, a large number of orthologous protein coding genes (Stein et al., 2003). Yet sex-related genes and genetic pathways have rapidly evolved across Caenorhabditis species (Civetta and Singh, 1998; Haag et al., 2002).

The C. elegans xol-1 ortholog has been identified in C. briggsae. Structural and genetic analysis has suggested that it could function as a regulator of sexual development and dosage compensation in C. briggsae (Luz et al., 2003). To the best of our knowledge, factors acting upstream of xol- 1 are completely unknown in C. briggsae. Although we could not identify a homolog of 21ux-1, C. briggsae is known to express a prg-1/Piwi homolog, RdRP and an array of WAGOs (Shi et al., 2013). To ask if C. briggsae xol-1 is regulated by piRNAs, we mutated the C. briggsae Piwi gene and monitored 22G-RNAs genome-wide. We found that 22G-RNAs targeting xol-1 mRNA were greatly diminished in the Piwi mutants (Figure 3C). Furthermore, we found that the xol-1 transcript level was increased by 3- to 4- fold in the mutant animals at the stage of L4 larvae and adult. Thus in both C. elegans and C. briggsae the piRNA pathway functions to repress xol-1 expression in the germline (Figure 3D).

DISCUSSION

The piRNA pathway is often discussed in the context of transposon and transgene suppression. Our findings identify a physiological role for a piRNA in regulating an endogenous gene in nematode. Specifically, we have shown that an X-chromosome piRNA regulates the maternal level of xol-1 mRNA and protein. xol-1 encodes a master regulator of dosage compensation and sex determination (Miller et al., 1988; Rhind et al., 1995). The 21ux-1 piRNA acts along with other maternally contributed factors, including SEX-1 mRNA or protein, to establish a delicate balance of XOL-1 and its regulators, such that X-signal elements can robustly specify sexual fates in response to the karyotype of XX and XO progeny (Figure 3E). This remarkably subtle, but very pathway-specific function of 21ux-1, demonstrates that a piRNA can confer physiologically important regulation on a germline mRNA.

piRNAs in gene regulation

The piRNA pathway is thought to initiate silencing by recruiting RdRP which templates 22G-RNA synthesis directly from the target mRNA. These 22G-RNAs are loaded onto WAGOs and deposited into mature gametes. In concert with chromatin modifiers, WAGOs/22G-RNA complexes can maintain transgenerational gene silencing independently of the Piwi pathway (Ashe et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2012; Shirayama et al., 2012). Nevertheless, Seth et al. (co-submitted) have shown that some transgenes require both the WAGO and Piwi pathways to maintain silencing, and that full repression of transgenes can be piRNA-dependent. The xol-1 locus provides an example of an endogenous gene that depends on both WAGO and Piwi pathways for its regulation.

Because of the extreme diversity of piRNA sequences and their ability to recognize targets with partial complementarity (Ashe et al., 2012; Bagijn et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2012; Shirayama et al., 2012), piRNAs should, in principal, target all germline transcripts. This notion has led to the proposal that endogenous mRNAs are protected (at least partially) by other mechanisms (See Discussion Below, Shirayama et al., 2012; Wedeles et al. 2013; Seth et al., 2013). Conceivably, over evolutionary time, germline mRNAs sample piRNA targeting through random nucleotide changes that strengthen or weaken base-pairing. Some piRNA–target interactions might lead to stable silencing (as seen for most transposons and some protein coding genes), while other interactions—e.g., between the 21ux-1 piRNA and the xol-1 mRNA—may lead to partial down-regulation. The degree of targeting and silencing at each transcript could in turn provide a source of heritable variation upon which natural selection can act.

It is interesting that xol-1 is not completely or permanently silenced upon piRNA targeting. Although the details are not understood, it is clear that mechanisms exist that oppose piRNA-induced silencing. At the DNA level, A/T rich clusters have been shown to counteract silencing and to promote C. elegans germline gene expression (Frokjaer-Jensen et al., 2016). At the RNA level, the CSR-1 Argonaute has been shown to promote the transitive activation of a silent transgene, and has been proposed to protect mRNAs from piRNA-mediated silencing (Seth et al., 2013; Wedeles et al., 2013). The csr-1 gene is essential for fertility and viability, and csr-1 mutants exhibit changes in the levels of many germline mRNAs (Claycomb et al., 2009; Gerson-Gurwitz et al., 2016; Yigit et al., 2006). Indeed, a recent study proposed that CSR-1 tunes germline gene expression broadly (Gerson-Gurwitz et al., 2016). The emerging picture from our studies and others is that there are many influences on germline gene expression and that these are likely to include, as yet, entirely undiscovered pathways. The present findings and those of Seth et al., (co-submitted) suggest that variations in the level of piRNA-target complementarity—within the context of other mechanisms that govern sensitivity/resistance to piRNA silencing—provides a rich regulatory milieu within which Argonautes have the potential to broadly shape (or tune) the profile of germline gene expression.

Non-coding RNAs in dosage compensation and sex determination

A role for 21ux-1 in dosage compensation and sex determination provides yet another example of an independently evolved non-coding RNA that functions to equalize sex-chromosome gene expression (Amrein and Axel, 1997; Brockdorff et al., 1992; Brown et al., 1992; Meller et al., 1997). McJunkin and Ambros (2017) recently showed that the mir-35 microRNA family exerts maternal control of sex determination in the early C. elegans embryo (McJunkin and Ambros, 2017). Thus, multiple small RNA pathways contribute to sex determination in C. elegans.

The regulation of xol-1 by 21ux-1 exhibits striking parallels to the likely independently evolved relationship between the Masculinizer (Masc) gene and the feminizing (Fem) piRNA in the Lepidopteran Bombyx mori (Kiuchi et al., 2014). Fem originates from the W chromosome and specifies female (ZW) development by silencing the Z-derived Masculinizer (Masc) mRNA. Masc encodes a CCCH-type zinc finger protein that controls dosage compensation and sex determination in Bombyx mori males (ZZ) (Kiuchi et al., 2014). Both the nematode and insect B. mori—separated by at least 700-million years of evolution—use piRNAs to regulate this dose-sensitive developmental mechanism, providing further support for the idea that piRNAs play important physiological roles in gene regulation in animals.

STAR★METHODS

• CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Craig C. Mello (Craig.Melloumassmed.edu)

• EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

C. elegans

The Bristol strain N2 was designated as the wild-type C. elegans strain. Other strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 and KEY RESOURCES TABLE. The C. elegans and C. briggsae strains were maintained with E. coli OP50 as diet on Nematode Growth Media (NGM) (Brenner, 1974). All animals were maintained at 20 °C unless otherwise indicated.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Flag | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F1804-200UG |

| Rat polyclonal anti-alpha-Tubulin | Bio-Rad | Cat#VMA00051 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (HRP) | Abcam | Cat#ab6789 |

| Goat Anti-Rat IgG H&L (HRP) | Abcam | Cat#ab97057 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Bacteria: OP50 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/OP50 |

| Bacteria: HT115 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/HT115(DE3) |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| CAS9 protein | Integrated DNA Technologies | Cat#1074181 |

| TRI Reagent | Molecular Research Center | Cat#TR118 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#AM1560 |

| SYBR Green PCR Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#4309155 |

| SuperScript IIIReverse Transcriptase | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#18080093 |

| Ex TaqDNA Polymerase | TaKaRa | Cat#RR001C |

| RNA 5' Polyphosphatase | Lucigen | Cat#RP8092H |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Small RNA sequencing data from HRDE-1/WAGO-9 IP | Shirayama et al., 2012 | GSE38724 |

| Small RNA sequencing data from rde-3 and mago-12 mutants | Gu et al., 2009 | GSE18215 |

| Small RNA sequencing data from prg-1 mutants | Lee et al., 2012 | GSE38723 |

| Small RNA sequencing data from wild-type and 21ux-1 mutants | This study | PRJNA398958 |

| Small RNA sequencing data C briggsaewild-type and piwi mutants | This study | PRJNA398958 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C. elegans: N2 Bristol | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/N2 |

| C. elegans:TY1807 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/TY1807 |

| C. elegans:NG41 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/NG41 |

| C. elegans:WM161 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/WM161 |

| C. elegans:WM191 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/WM191 |

| C. elegans:CB1489 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/CB1489 |

| C. briggsae:AF16 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/AF16 |

| C. elegans:WM286 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | https://cgc.umn.edu/strain/WM286 |

| Additional C. elegans strains in this study are listed in Supplemental Table 1 | This paper | Supplemental Table 1 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| miRNA cloning linker 1: 5' rAppCTGTAGGCACCATCAAT/3ddC/ 3' | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| xol-1 (C. elegans)_sense: GGAGCGAAAACAGTCCAGTC | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| xol-1 (C. elegans)_antisense: ATCATGTGCATGCTTCGGTA | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| act-3 (C. elegans)_sense: GGCCCAATCCAAGAGAGGTATCC | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| act-3 (C. elegans)_antisense: GGGCAACACGAAGCTCATTGTA | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| xol-1 (C. briggsae)_sense: GACCACCCATATCGCAAACG | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| xol-1 (C. briggsae)_antisense: TCAACACCTCGCAAACCCAG | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| act-5 (C. briggsae)_sense: AGCGTGGATACACCTTCACC | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| act-5 (C. briggsae)_antisense:AATGAAAGCTGGCTGGAAGA | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Ahringer C. elegans RNAi library: RNAi controlplasmid: pL4440 | Source BioScience | http://www.sourcebioscience.com/products/life-science-research/clones/rnai-resources/c-elegans-rnai-collection-ahringer/ |

| Ahringer C. elegans RNAi library: RNAi sex-1 knockdown: pL4440-sex-1 | Source BioScience | http://www.sourcebioscience.com/products/life-science-research/clones/rnai-resources/c-elegans-rnai-collection-ahringer/ |

| Ahringer C. elegans RNAi library: RNAi sdc-2 knockdown: pL4440-sdc-2 | Source BioScience | http://www.sourcebioscience.com/products/life-science-research/clones/rnai-resources/c-elegans-rnai-collection-ahringer/ |

| pRF4 | Mello CC et al., 1991 | https://www.addgene.org/vector-database/7880/ |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Bowtie | Langmead et al., 2009 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml |

| GraphPad Prism 6 | GraphPad Software, Inc. | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Perl | The Perl Foundation | https://www.perl.org/ |

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of transgenic strains by CRISPR/CAS9

21ux-1 (anti-gfp) and C. briggsae piwi mutants were generated by a co-CRISPR strategy and unc-22 sgRNA served as a co-injection marker to enrich CRISPR/CAS9-mediated genome editing events (Kim et al., 2014). 21ux-1 deletion, xol-1 with N terminal gfp::2XFlag::auxin-based degron sequences, 21ux-1 sex-1 double, and 21ux-1 xol-1 sex-1 triple mutant strains were generated using CRISPR/CAS9 ribonucleoprotein complexes (Paix et al., 2015). The transgenic strains made by CRISPR/CAS9 are listed in Table S1. The vector pRF4 expressing rol-6 (su1006), a dominant allele conferring a roller phenotype, served as a co-injection marker.

Scoring viability and masculinized animals

Five gravid hermaphrodites (wild-type and mutants) were placed on individual plate and allowed to lay embryos for six to eight hours. The total number of eggs was scored. Surviving animals were counted in a period of 4 days at room temperature. Survivors that failed to reach L4 stage were considered inviable.

The HT115 RNAi feeding strains (sex-1 and sdc-2) were picked from the C. elegans RNAi Collection (Source BioScience). All RNAi experiments were performed as described previously (Kamath et al., 2003). Specifically, synchronized L1 animals were placed on plates spotted with corresponding RNAi strains. Five gravid adults were transferred onto fresh RNAi plates, eggs were counted, and survivors were scored as described above. The percentage of masculinized animals was calculated as the ratio of total number of pseudomale to total number of surviving animals.

Small RNA cloning

Total RNAs were isolated from adult worms using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center). Small RNAs were enriched using MirVana Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples from wild-type and mutants were pretreated with a homemade 5’ Polyphosphatase or RNA 5-Polyphosphatase (Lucigen) and were ligated to the miRNA cloning linker 1 (5' rAppCTGTAGGCACCATCAAT/3ddC/ 3', IDT). The 5’ linkers containing 6 nt barcode were ligated using T4 RNA ligase (NEB). The ligated products were converted to cDNA using SuperScript III (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Libraries were amplified by PCR and sequenced using the HiSeq systems (Illumina) at the UMass Medical School Deep Sequencing facility.

Data analysis

Small RNA sequencing data were analyzed using a reported pipeline (Gu et al., 2012). Briefly, sequencing reads were first sorted according to barcode sequences, and both 5’ and 3’ adaptor sequences were removed. Reads starting with G/A and 21~23 nt in length were mapped to the reference genome by allowing at most two mismatches. To account for differences in sequencing depth between samples, reads were normalized to library size. Normalized counts were visualized in the UCSC genome browser. All scripts are available upon request.

Quantitative RT-PCR

The reverse transcription (RT) was performed using antisense primers by SuperScript III (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT reaction was conducted in at least triplicate-reactions. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All primers are listed in KEY RESOURCES TABLE. Statistical analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel. Error bars in the graph represent the standard deviation (SD).

Western blotting analysis

Cell lysate were prepared from synchronized population of L4 larvae and gravid adults. 50 µg lysate were loaded onto the precast polyacrylamide gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific), subjected to electrophoresis, and transferred onto the PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad) with Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad). The primary antibodies used were anti-FLAG (M2, Sigma) and anti-alpha-Tubulin (Bio-Rad). The secondary antibodies were goat-anti-mouse HRP (Abcam) and goat-anti-rat HRP (Abcam) respectively.

Imaging and Microscopy

To collect DIC and epifluorescence images, wild-type and mutant animals were first treated with 0.2 mM levamisole and mounted on the RITE-ON glass slide (Becton, Dickinson and Company). The Axioplan2 Microscope (Zeiss) was used to collect the images and images were processed using AxioVision software (Zeiss).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Genetic crosses and qRT-PCR experiments were performed as independent biological replicates and the number of replicates was shown in the figure legends. All statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 7 or Microsoft Excel. Standard Student’s t-test was conducted. p-values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

HRDE-1/WAGO-9 IP data are available from GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) under the accession number GSE38724. Small RNA sequencing data from rde-3 and mago-12 mutants are available under accession number GSE18215. Small RNA sequencing data from prg-1 mutants are under the accession number GSE38723. Small RNA sequencing data from wild-type, 21ux-1 mutants, C briggsae wild-type, and piwi mutants are available under PRJNA398958.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Strains used in this study and their genotypes. Related to the STAR Methods

Highlights.

An X-linked piRNA, 21ux-1, targets xol-1 and represses its expression in C. elegans

21ux-1 acts with sex-1 to promote dosage compensation and sex determination

The piRNA pathway regulates the expression of the xol-1 ortholog in C. briggsae

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Farbound and B.J. Meyer, for suggestions; D. Conte for critical review of the manuscript; members of Mello and Ambros labs for discussions, W. Gu for providing the reagents for library preparation; E. Kittler and the UMass Deep Sequencing Core for Illumina sequencing; T. Zheng for the assistance in generating C. briggsae Piwi mutant strain. Some of the strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center supported by NIH (P40 OD010440). This work was supported by the Hope Funds for Cancer Research Postdoctoral fellowship (HFCR-15-06-03) and NIH Pathway to Independence Award (GM124460) to W.T.; an NIH grant (HD078253) to Z.W.; NIH grants (GM058800 and HD078253) to C.C.M. C.C.M. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions Conceptualization, W. T. and C. C. M.; Investigation, W. T., M. S., S. T., E. Z., Q. L., M. S., Z.W., and C. C. M.; Writing – Original Draft, W. T. and C. C. M.; Writing–Review & Editing, W. T., and C. C. M.; Funding Acquisition, W. T. Z.W., and C. C. M.; Supervision, C. C. M.

References

- Amrein H, Axel R. Genes expressed in neurons of adult male Drosophila. Cell. 1997;88:459–469. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81886-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe A, Sapetschnig A, Weick EM, Mitchell J, Bagijn MP, Cording AC, Doebley AL, Goldstein LD, Lehrbach NJ, Le Pen J, et al. piRNAs can trigger a multigenerational epigenetic memory in the germline of C. elegans. Cell. 2012;150:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagijn MP, Goldstein LD, Sapetschnig A, Weick EM, Bouasker S, Lehrbach NJ, Simard MJ, Miska EA. Function, targets, and evolution of Caenorhabditis elegans piRNAs. Science. 2012;337:574–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1220952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista PJ, Ruby JG, Claycomb JM, Chiang R, Fahlgren N, Kasschau KD, Chaves DA, Gu W, Vasale JJ, Duan S, et al. PRG-1 and 21U-RNAs interact to form the piRNA complex required for fertility in C. elegans. Molecular cell. 2008;31:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockdorff N, Ashworth A, Kay GF, McCabe VM, Norris DP, Cooper PJ, Swift S, Rastan S. The product of the mouse Xist gene is a 15 kb inactive X-specific transcript containing no conserved ORF and located in the nucleus. Cell. 1992;71:515–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90519-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Hendrich BD, Rupert JL, Lafreniere RG, Xing Y, Lawrence J, Willard HF. The human XIST gene: analysis of a 17 kb inactive X-specific RNA that contains conserved repeats and is highly localized within the nucleus. Cell. 1992;71:527–542. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90520-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmi I, Kopczynski JB, Meyer BJ. The nuclear hormone receptor SEX-1 is an X-chromosome signal that determines nematode sex. Nature. 1998;396:168–173. doi: 10.1038/24164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Simard MJ, Tabara H, Brownell DR, McCollough JA, Mello CC. A member of the polymerase beta nucleotidyltransferase superfamily is required for RNA interference in C. elegans. Current biology : CB. 2005;15:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civetta A, Singh RS. Sex-related genes, directional sexual selection, and speciation. Molecular biology and evolution. 1998;15:901–909. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claycomb JM, Batista PJ, Pang KM, Gu W, Vasale JJ, van Wolfswinkel JC, Chaves DA, Shirayama M, Mitani S, Ketting RF, et al. The Argonaute CSR-1 and its 22G-RNA cofactors are required for holocentric chromosome segregation. Cell. 2009;139:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan A, Wolfe KH. Fourfold faster rate of genome rearrangement in nematodes than in Drosophila. Genome research. 2002;12:857–867. doi: 10.1101/gr.172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PP, Bagijn MP, Goldstein LD, Woolford JR, Lehrbach NJ, Sapetschnig A, Buhecha HR, Gilchrist MJ, Howe KL, Stark R, et al. Piwi and piRNAs act upstream of an endogenous siRNA pathway to suppress Tc3 transposon mobility in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Molecular cell. 2008;31:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes HE, Berlin DS, Lapidus DM, Nusbaum C, Davis TL, Meyer BJ. Dosage compensation proteins targeted to X chromosomes by a determinant of hermaphrodite fate. Science. 1999;284:1800–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang W, Wang X, Bracht JR, Nowacki M, Landweber LF. Piwi-interacting RNAs protect DNA against loss during Oxytricha genome rearrangement. Cell. 2012;151:1243–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farboud B, Nix P, Jow MM, Gladden JM, Meyer BJ. Molecular antagonism between X-chromosome and autosome signals determines nematode sex. Genes & development. 2013;27:1159–1178. doi: 10.1101/gad.217026.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer-Jensen C, Jain N, Hansen L, Davis MW, Li Y, Zhao D, Rebora K, Millet JRM, Liu X, Kim SK, et al. An Abundant Class of Non-coding DNA Can Prevent Stochastic Gene Silencing in the C. elegans Germline. Cell. 2016;166:343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerson-Gurwitz A, Wang S, Sathe S, Green R, Yeo GW, Oegema K, Desai A. A Small RNA-Catalytic Argonaute Pathway Tunes Germline Transcript Levels to Ensure Embryonic Divisions. Cell. 2016;165:396–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden JM, Farboud B, Meyer BJ. Revisiting the X:A signal that specifies Caenorhabditis elegans sexual fate. Genetics. 2007;177:1639–1654. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.078071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden JM, Meyer BJ. A ONECUT homeodomain protein communicates X chromosome dose to specify Caenorhabditis elegans sexual fate by repressing a sex switch gene. Genetics. 2007;177:1621–1637. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh WS, Falciatori I, Tam OH, Burgess R, Meikar O, Kotaja N, Hammell M, Hannon GJ. piRNA-directed cleavage of meiotic transcripts regulates spermatogenesis. Genes & development. 2015;29:1032–1044. doi: 10.1101/gad.260455.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou LT, Dai P, Yang JH, Xue Y, Hu YP, Zhou Y, Kang JY, Wang X, Li H, Hua MM, et al. Pachytene piRNAs instruct massive mRNA elimination during late spermiogenesis. Cell research. 2014 doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Lee HC, Chaves D, Youngman EM, Pazour GJ, Conte D, Jr, Mello CC. CapSeq and CIP-TAP identify Pol II start sites and reveal capped small RNAs as C. elegans piRNA precursors. Cell. 2012;151:1488–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Shirayama M, Conte D, Jr, Vasale J, Batista PJ, Claycomb JM, Moresco JJ, Youngman EM, Keys J, Stoltz MJ, et al. Distinct argonaute-mediated 22G-RNA pathways direct genome surveillance in the C. elegans germline. Molecular cell. 2009;36:231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag ES, Wang S, Kimble J. Rapid coevolution of the nematode sex-determining genes fem-3 and tra-2. Current biology : CB. 2002;12:2035–2041. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J, Zellan JD, Albertson DG. Identification of a candidate primary sex determination locus, fox-1, on the X chromosome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1994;120:3681–3689. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano C, Wang J, Lin H. Uniting germline and stem cells: the function of Piwi proteins and the piRNA pathway in diverse organisms. Annual review of genetics. 2011;45:447–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Ishidate T, Ghanta KS, Seth M, Conte D, Jr, Shirayama M, Mello CC. A co-CRISPR strategy for efficient genome editing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2014;197:1069–1080. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.166389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi T, Koga H, Kawamoto M, Shoji K, Sakai H, Arai Y, Ishihara G, Kawaoka S, Sugano S, Shimada T, et al. A single female-specific piRNA is the primary determiner of sex in the silkworm. Nature. 2014;509:633–636. doi: 10.1038/nature13315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HC, Gu W, Shirayama M, Youngman E, Conte D, Jr, Mello CC. C. elegans piRNAs mediate the genome-wide surveillance of germline transcripts. Cell. 2012;150:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz JG, Hassig CA, Pickle C, Godzik A, Meyer BJ, Wilson IA. XOL-1, primary determinant of sexual fate in C. elegans, is a GHMP kinase family member and a structural prototype for a class of developmental regulators. Genes & development. 2003;17:977–990. doi: 10.1101/gad.1082303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McJunkin K, Ambros V. A microRNA family exerts maternal control on sex determination in C. elegans. Genes & development. 2017;31:422–437. doi: 10.1101/gad.290155.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller VH, Wu KH, Roman G, Kuroda MI, Davis RL. roX1 RNA paints the X chromosome of male Drosophila and is regulated by the dosage compensation system. Cell. 1997;88:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Plenefisch JD, Casson LP, Meyer BJ. xol-1: a gene that controls the male modes of both sex determination and X chromosome dosage compensation in C. elegans. Cell. 1988;55:167–183. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll M, Akerib CC, Meyer BJ. X-chromosome-counting mechanisms that determine nematode sex. Nature. 1997;388:200–204. doi: 10.1038/40669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paix A, Folkmann A, Rasoloson D, Seydoux G. High Efficiency, Homology-Directed Genome Editing in Caenorhabditis elegans Using CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. Genetics. 2015;201:47–54. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.179382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CM, Wong C, Bhalla N, Carlton PM, Weiser P, Meneely PM, Dernburg AF. HIM-8 binds to the X chromosome pairing center and mediates chromosome-specific meiotic synapsis. Cell. 2005;123:1051–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Oviedo NJ, Jennings JR, Jenkin JC, Sanchez Alvarado A. SMEDWI-2 is a PIWI-like protein that regulates planarian stem cells. Science. 2005;310:1327–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.1116110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind NR, Miller LM, Kopczynski JB, Meyer BJ. xol-1 acts as an early switch in the C. elegans male/hermaphrodite decision. Cell. 1995;80:71–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RJ, Weiner MM, Lin H. PIWI proteins and PIWI-interacting RNAs in the soma. Nature. 2014;505:353–359. doi: 10.1038/nature12987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby JG, Jan C, Player C, Axtell MJ, Lee W, Nusbaum C, Ge H, Bartel DP. Large-scale sequencing reveals 21U-RNAs and additional microRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in C. elegans. Cell. 2006;127:1193–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth M, Shirayama M, Gu W, Ishidate T, Conte D, Jr, Mello CC. The C. elegans CSR-1 Argonaute Pathway Counteracts Epigenetic Silencing to Promote Germline Gene Expression. Developmental cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Montgomery TA, Qi Y, Ruvkun G. High-throughput sequencing reveals extraordinary fluidity of miRNA, piRNA, and siRNA pathways in nematodes. Genome research. 2013;23:497–508. doi: 10.1101/gr.149112.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M, Seth M, Lee HC, Gu W, Ishidate T, Conte D, Jr, Mello CC. piRNAs initiate an epigenetic memory of nonself RNA in the C. elegans germline. Cell. 2012;150:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, Sarkies P, Ikegami K, Doebley AL, Goldstein LD, Mitchell J, Sakaguchi A, Miska EA, Ahmed S. Reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling restores germ cell immortality to caenorhabditis elegans Piwi mutants. Cell reports. 2014;7:762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:246–258. doi: 10.1038/nrm3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper M, Milne CA, Hodgkin J. Genetic and molecular analysis of fox-1, a numerator element involved in Caenorhabditis elegans primary sex determination. Genetics. 1999;151:617–631. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LD, Bao Z, Blasiar D, Blumenthal T, Brent MR, Chen N, Chinwalla A, Clarke L, Clee C, Coghlan A, et al. The genome sequence of Caenorhabditis briggsae: a platform for comparative genomics. PLoS biology. 2003;1:E45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Kelly WG, Ercan S, Lieb JD. Regulation of the X chromosomes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2014;6 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Reinke V. A C. elegans Piwi, PRG-1, regulates 21U-RNAs during spermatogenesis. Current biology : CB. 2008;18:861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedeles CJ, Wu MZ, Claycomb JM. Protection of Germline Gene Expression by the C. elegans Argonaute CSR-1. Developmental cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weick EM, Miska EA. piRNAs: from biogenesis to function. Development. 2014;141:3458–3471. doi: 10.1242/dev.094037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yigit E, Batista PJ, Bei Y, Pang KM, Chen CC, Tolia NH, Joshua-Tor L, Mitani S, Simard MJ, Mello CC. Analysis of the C. elegans Argonaute family reveals that distinct Argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell. 2006;127:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Strains used in this study and their genotypes. Related to the STAR Methods