Abstract

(3-Hydroxy-2-naphthalenyl)methyl (NQMP) group represents an efficient photo-cage for fluorescein – based dyes. Thus, irradiation of 6-NQMP ether of 2’-hydroxymethyl fluorescein with low-intensity UVA light results in 4 fold increase in emission intensity. Photoactivation of non-fluorescent NQMP-caged 3-allyloxyfluorescein produces highly emissive fluorescein mono ether. To facilitate conjugation of the caged dye to the substrate of interest via click-chemistry, the allyloxy appendage was functionalized with an azide moiety.

Graphical Abstract

Labeling of biological substrates with fluorescent tags represents one of the most useful tools in biochemistry and cell biology.1 Fluorogenic probes that change the intensity (or more precisely, quantum yield) of fluorescence under the action of an external stimulus add extra dimension to these methods.2 Thus, recently developed photoactivatable fluorophores (PAFs), permit spatiotemporal control of the emission of fluorescent reporters.3 PAFs are crucial components of several advanced bio-imaging techniques, such as local activation of fluorescent molecular probes (LAMP)4, photo-activated localization microscopy (e.g., PALM, FPALM, STORM),5,6 and other methods for ultra-resolution microscopy.7 PAFs have also found use in protein tracking/trafficking studies in cells,8 as well as fate-mapping of cells in organisms9.

Several successful approaches to the design of PAFs have been reported recently. Enhancement of fluorescent efficiency can be accomplished by photochemical rearrangement of the precursor molecule that increases the π-conjugation;10 push-pull fluorophores can be turned on by light-induced change in the electronic properties of substituents.11 The blinking properties of some fluorescent proteins can employed to achieve switchable emission.12 However, the most popular strategy in PAF design is caging, i.e., use of photolabile protecting groups (PPGs)13 to alter the emission of conventional fluorescent dyes. Irradiation of the caged fluorophore removes the PPG and releases the dye.6,14,15 The main advantage of the latter approach is its compatibility with well-developed fluorescent imaging techniques. While o-nitrobenzyl-based PPGs are most commonly employed in the development of PFA,6,14 this family of PPGs has some significant drawbacks. The substrate release from o-nitrobenzyl cage is often slow, as it proceeds through several dark steps,16 and its efficiency depends on the pH of the solution and the basicity of the caged functionality.13 In addition, uncaging is accompanied by the formation of reactive and cytotoxic o-nitrosobenzoyl byproducts.13 To alleviate these complications, the utility of other caging groups is being explored.15

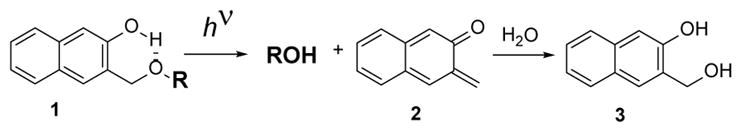

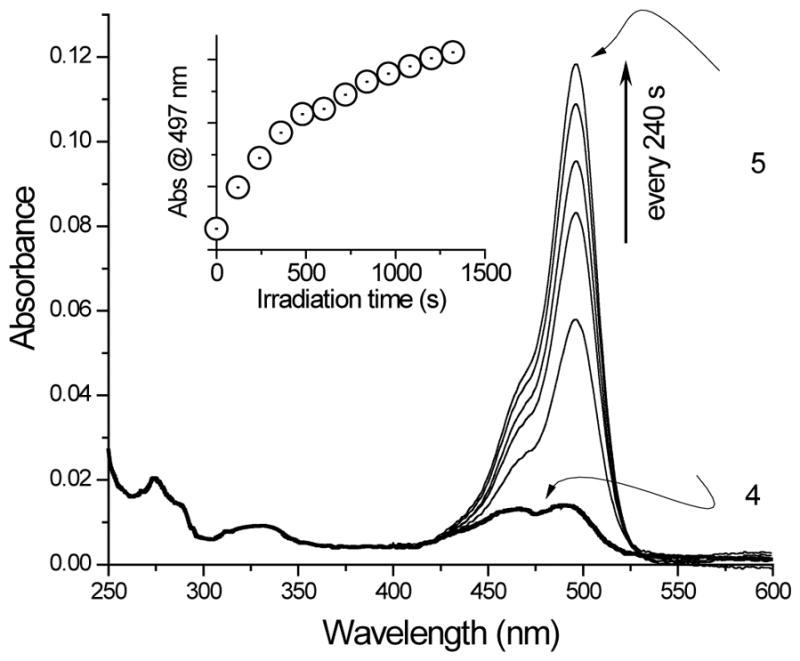

In this report, we describe the use of recently developed (3-hydroxyl-2-naphthyl)methyl (NQMP)17 photolabile protecting group for the caging of fluorescein-based dyes. Irradiation of NQMP ethers or esters 1 with 300 – 350 nm light results in the efficient cleavage of the benzylic C-O bond and the release of a substrate (Scheme 1). The o-naphthoquinone methide (oNQM) intermediate 2 is rapidly (τ ~ 7 ms) hydrated to 3-(hydroxymethyl)naphthalen-2-ol (3, Scheme 1).18 The substrate release from NQMP cage is efficient (Φ = 0.2 – 0.3) and very fast (~105 s−1) making this PPG suitable for time-resolved experiments.

Scheme 1.

Photochemical substrate release from NQMP cage

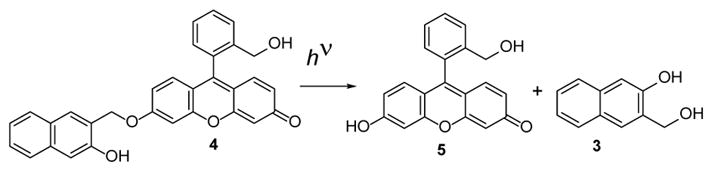

We decided to test the utility of NQMP group for the PAF development on the example of NQMP-caged fluorescein derivative 4. We hypothesized that this compound should have a low fluorescent efficiency since its vinyl ether analog is essentially non-fluorescent at physiological pH.19 Irradiation of 4 was expected to release highly fluorescent 6-hydroxy-9-(2-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl-3H-xanthen-3-one (5, Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Photo-release of 6-hydroxy-9-(2-(hydroxymethyl) phenyl)-3H-xanthen-3-one (5) from NQMP cage.

Photoactivatable fluorophore 4 was synthesized in four steps from fluorescein (Scheme 3). Esterification of the latter was achieved by refluxing in alcohol with 1—3 molar equivalents of boron trifluoride etherate. This procedure cleanly affords the corresponding fluorescein ethyl ester 6. It is worth noting that conventional esterification of fluorescein in the presence of strong mineral acids produces a significant amount of byproducts and requires complex work-up procedures.20 Williamson esterification of fluorescein ethyl ester 6 with the MEM-protected 3-(bromomethyl) -3-naphthol 7* at room temperature gave mono NQMP-caged fluorescein ethyl ester 8 in 99 % isolated yield. An ethoxycarbonyl moiety of 8 was reduced to alcohol with DIBAL. Even mild hydride sources, e.g. NaBH4, are known to reduce p-quinone methide fragment of fluorescein to the corresponding phenol.21 To re-oxidize it to the quinoid form, the crude product mixture was treated with DDQ19a to afford 9. Subsequent attempts to remove the MEM (as well as MOM) protecting group from 9 using strong acids (e.g., HCl, TFA, etc.) were accompanied by the significant hydrolysis of the NQMP ether. Fortunately, incubation of 9 in 95 % aqueous methanol at 40 °C in the presence of amberlyst-15 resin22 produced NQMP-caged dye 4 in 60% yield (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of NQMP-caged 6-hydroxy-9-(2-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl)-3H-xanthen-3-one (4).

Reagents and conditions: (a) EtOH, BF3.Et2O, reflux, 85 %; (b) i) DIBALH, CH2Cl2; ii) DDQ, Et2O, 52 % over 2 steps; (c) Amberlist-15, 95 % Methanol, 40 °C, 60 %.

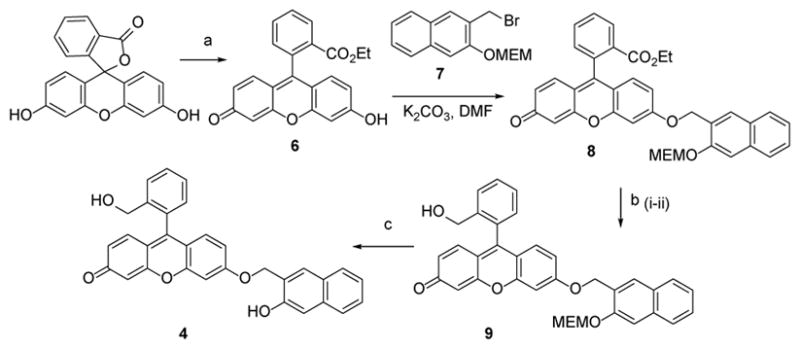

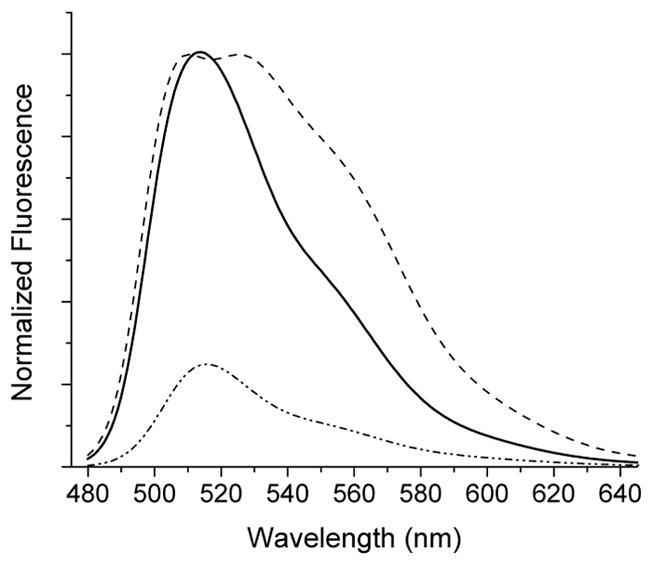

The UV spectrum of mono NQMP-caged fluorescein derivative 4 in aqueous solution at pH = 7.4 (PBS buffer) shows two absorbance bands at 467 nm and 491 nm with similar intensity (log ε = 3.7, Fig. 1). The presence of these bands suggests that caged dye 4 exists in a quinoid form to some extent. This suggestion is supported by significant fluorescence of 4 (ΦFL = 0.29—0.32) with an emission maximum at 513 NM (Fig. 2). The emission efficiency of 4 is similar to that of the mono anion of fluorescein. 1b irradiation (thin lines, every 240 s). The inset shows the change of absorbance at 497 nm vs irradiation time.

Figure 1.

UV spectra of 2.8 μM aqueous solution of 4 (in PBS buffer + 2 % DMSO, pH 7.4) in the dark (thick line), and during 350 nm

Figure 2.

Emission spectra (λexc = 460 nm) of 3.4 μM solution of 4 (in PBS buffer + 2 % DMSO, pH 7.4) in the dark (dash-dotted line); after 10 min of 300 nm irradiation (solid line), and after 20 min exposure to 350 nm light (dashed line).

Irradiation of a PBS solution of caged dye 4 using 300 NM or 350 NM fluorescent lamps results in the efficient release of 6-hydroxy-9-(2-(hydroxy-methyl)phenyl)-3H-xanthen-3-one 5 (Scheme 2), as evident from the rise of the characteristic UV band at 497 nm (Fig. 1). HRMS-ESI of the resulting photolysate confirmed the clean release of the fluorescent dye 5 (Fig. S1).23 Photo-chemical cleavage of the NQMP ether in caged dye 4 also resulted in a 3–4 fold enhancement of fluorescent efficiency (ΦFl = 0.74—0.93, Fig. 2). It is interesting to note that prolonged irradiation at 350 nm does not significantly affect the UV spectrum of 5 but results in the splitting of the emission band at 513 m in two (λmax = 509 and 525 nm, Fig.2). This observation suggests that secondary photochemistry does not affect the fluorescent core of 5 but rather occur in the aromatic side chain. We believe that this phenomenon is probably due to the oxidation of the benzylic hydroxy group.

While photoactivation of caged dye 4 produces a dramatic enhancement of fluorescence, the maximum achievable contrast using this PAF is below 1:4 (dark vs exposed). Complete quenching of the emission of fluorescein-based dyes can be achieved by etheri-fication of both phenols. Although the symmetrical caging of these moieties with photolabile protecting groups is a synthetically attractive approach, the removal of two protecting groups requires prolonged irradiation and increases the probability of photo-bleaching of the fluorophore. Incomplete uncaging, on the other hand, produces a mixture of three forms of the PAF, reducing the contrast and hampering quantitative measurements. Alternatively, only one phenolic hydroxyl can be caged with a photolabile protecting group, while the other is irreversibly capped. This strategy results in improved activation efficiency and excellent image contrast.20b,24 Following this design, we have developed NQMP-caged fluorescein (NQMP-FL-A 10), with a “clickable” linker attached to the second phenyl ring. It is important to note that the order of alkylation of the phenolic hydroxy groups is crucial to the success of the synthesis of unsymmetrical fluorescein derivatives. Thus, alkylation of fluorescein with bromide 7 prevented the subsequent installation of the allyl group. The working strategy for the preparation of PFA 10 is outlined in Scheme 4.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of caged fluorescein derivative 10.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Allyl bromide, CsCO3, 60 °C 94 %; (b) 1N NaOH, 95 %; (c) 7, Ag2O, benzene, 77 %; (d) Amberlist-15, aq. MeOH, 50 °C, 74 %; (e) 19, Et3N. CH2Cl2, 53 %.

Treatment of fluorescein with allyl bromide in the presence of cesium carbonate resulted not only in alkylation of one phenol moiety but also in lactone ring opening and the formation of allyl ester 11. Subsequent saponification afforded the air-sensitive fluores-cein lactone 12. Alkylation of the second phenolic hydroxy group in mono-alkylated fluorescein is often complicated by the ring-chain tautomerism of the dye.20b However, silver(I) oxide-mediated alkylation of 12 with bromide 7 in benzene produced the target unsymmetrical bis-alkylated fluorescein 13 in an excellent yield. The removal of the 2-(ethoxymethoxy) protecting group was achieved in 74 % yield using amberlyst-15 resin in 95 % aqueous methanol at 50 °C (Scheme 4).

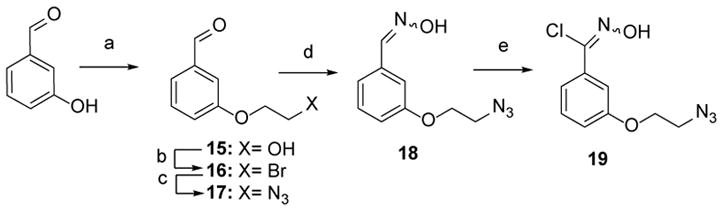

The allyl group in NQMP-caged fluorescein 14 provides a convenient handle for subsequent functionalization or conversion into various reactive groups, such as aldehydes, alcohols, and epoxides. We decided to exploit the dipolarophilic properties of this moiety and introduced azide-terminated linker via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of nitrile oxide. The latter was generated in situ25 from N-hydroxycarboximdoyl chloride 19 (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Preparation of 3-(2-azidoethoxy) -N-hydroxybenzenecarboximidoyl chloride

Reagents and conditions: (a) i) TBSOCH2CH2Br*, K2CO3, DMF, 46 %; ii) HF(aq), 87 %; (b) Imidazole, Br2, Ph3P, CH2Cl2, 96 %; (c) NaN3, DMF, 69 %; (d) NH2OH.HCl, CH2Cl2, 88 %; (e) NCS, DMF, 65 %.

The nitrile oxide precursor 19 was synthesized from commercially available m-hydroxybenzaldehyde. Alkylation of the latter with TBDMS-protected bromoethanol, followed by removal of the silyl protecting group, afforded 3-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-benzaldehyde (15). Bromination of aldehyde 15 followed by substitution with sodium azide produced azido aldehyde 17 in a good yield. Treatment of aldehyde 17 with hydroxylamine hydrochloride gave the corresponding aldoxime 18 in 88 % yield. The key intermediate 3-(2-azidoethoxy)-N-hydroxybenzenecarboximidoyl chloride 19 was obtained in 65 % yield from aldoxime 18 using N-chlorosuccinimide.

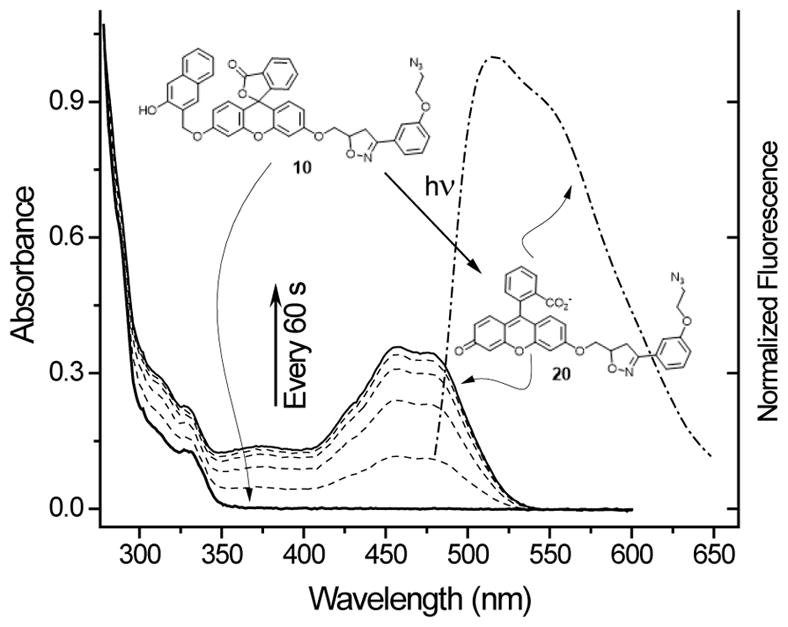

Phosphate buffered or aqueous methanol solutions of NQMP-caged fluorophore 10 have no detectable absorbance bands above 350 nm (Figure 3). Irradiation of this solution with 300 nm fluorescent tubes (4 W) causes a rapid rise in characteristic “quinoid” absorbance bands at 452 and 496 nm due to release of fluorescein mono-ether 20 (Figure 3). Complete conversion is achieved in 5 min. Use of 350 nm lamps requires four times longer exposure, apparently due to lower extinction coefficient of NQMP chromophore at this wavelength.17 Upon 460 nm excitation, the photolysate is intensely fluorescent (λmax = 515 nm, ΦFL = 0.22–25, Figure 3). The absorbance spectrum shows two maxima, which also suggests the presence of tautomeric forms of uncaged dye 21, typical of fluorescein derivatives.

Figure 3.

UV spectra of 0.08 mM aqueous methanol solution of 10 in the dark (thick line), and during 300 nm irradiation (dotted lines, every 60 s). Emission spectra (dash-dotted line, λexc = 460 nm) of 2.3 μM solution of 20 (in PBS buffer + 9 % DMSO, pH 7.4).

To test the suitability of the azide moiety in 10 for the derivatization of various substrates using click chemistry, we evaluated its reactivity in strain-promoted copper-free cycloaddition (SPAAC) reaction. The rate of reaction of 10 with oxodibenzocyclooctyne (ODIBO, 21)26 was measured by UV spectroscopy at 25±0.1 °C in methanol solution following the decay of the characteristic 305 nm absorbance of ODIBO (Figure 4). The observed reaction rate between 50 μM of ODIBO and 0.22 mM of caged fluorophore 10 (kOBS=(5.11±0.01)*10−4 s−1) allowed us to estimate the bimolecular rate of this SPAAC reaction at k= 2.3±0.2 M−1s−1. This value is similar to the rates observed in cycloaddition of aliphatic azides to ODIBO.26 The formation of cycloadduct 22 was confirmed by HRMS of the product.*

Figure 4.

Changes in absorption at 305 nm accompanying the reaction of ODIBO (21, 50 μM) with an azide moiety of NQMP-caged fluorophore 10 (0.22 mm) in methanol at 25.0 ±0.1 °C.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated that (3-hydroxy-2-naphthalenyl)methyl (NQMP) photolabile protecting group is suitable for the development of photoactivatable fluorophores (PAFs). Two NQMP-caged derivatives of fluorescein were prepared following a relatively straightforward synthetic sequence. These caged compounds are not fluorescent or have low emission in the dark. The irradiation of aqueous or methanol solutions of NQMP-caged fluorophores with low-intensity 300 and 350 nm light results in the efficient release of the fluorescent dye and dramatic enhancement of emission. NQMP-caged fluorophore can be equipped with a reactive moiety for convenient attachment to a biological molecule, polymer, surface, or other substrate. We have demonstrated derivatization of NQMP-caged fluorescein with azide-terminated linker. The latter was subsequently utilized for copper-free ligation (SPAAC) to oxadibenzocyclooctyne (ODIBO). Feasibility studies of the use of NQMP-caged fluorescein 20 for fate-mapping in zebra fish embryos are underway in our laboratory.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Methods

All organic solvents were dried and freshly distilled before use. Flash chromatography was performed using 40–75 μm silica gel. All NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 using 400 MHz instruments and HRMS data was analyzed using ion trap or Q-TOF mass spectrometers unless otherwise noted.

Photochemical activation of PAF 4 and 10 was conducted by the irradiation of the reaction mixture in a merry-go-round photo-chemical reactor equipped with eight fluorescent UV lamps (4W, 300 or 350 nm).

Fluorescence measurements were conducted in aqueous buffers containing 4–9 % of DMSO as co-solvent at 2.3 – 3.4 μM concentrations. Emission spectra were recorded using 460 nm excitation light. The excitation source and the detector slit were set to 1 nm and 5 nm respectively. Fluorescence quantum yields were determined using fluorescein in 0.1 N NaOH (ΦFl = 0.95)27 as the standard reference.

Kinetics

Accurate rate measurements were conducted in methanol at 25.0 ±0.1 °C under pseudo first order conditions using UV-Vis spectrometer. Reaction of ODIBO with excess azide was monitored by the decay of cyclooctyne absorbance at 305 nm.

Materials

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received unless otherwise noted.

Ethyl 2-(6-hydroxy-3-oxo-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate (6).19

BF3.OEt2 (9.0 mL, 72 mmol) was added dropwise to a suspension of fluorescein (3.3g, 8.9 mmol) in EtOH (30 mL) and the reaction mixture was refluxed overnight with an addition funnel loaded with molecular sieves attached. The reaction mixture was cooled, quenched with water and diluted with EtOAc (100 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3 x 50 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with water (2 x 50 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and the solvents removed in vacuum to afford crude ethyl 2-(6-hydroxy-3-oxo-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate 6 (3.2 g, 8.9 mmol, 99 %) as a dark red solid which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): 8.17 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 2H), 6.54 (m, 3H), 3.95 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 0.85 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): 166.2, 164.9, 157.1, 152.1, 135.0, 134.1, 131.7, 131.0, 130.5, 115. 7, 104.3, 53.3, 41.1, 40.9, 40.7, 40.5, 40.3, 40.0, 39.8.

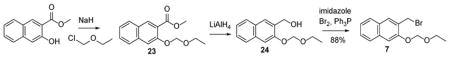

Preparation of 2-(bromomethyl)-3-(ethoxymethoxy)naphthalene (7).

(3-(Ethoxymethoxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methanol (24)

Sodium hydride (833 mg, 23 mmol) was added to an ice-cold solution of methyl 3-hydroxy-2-naphthoate (1.52 g, 7.5 mmol) in THF (80 mL). The mixture was stirred for 20 min and chloromethyl ethyl ether (1.40 mL, 15 mmol) was added dropwise. The solution was allowed to warm to r.t., stirred overnight, and quenched with 5% HCl (20 mL). The crude ether 23 was extracted with ether (3 x 50mL). The organic layer was washed with brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed in vacuo.

Powered lithium aluminum hydride (146 mg, 3.8 mmol) was added in portions to a solution of crude 23 (500 mg, 1.9 mmol) in 20 mL of THF at 0 °C. The mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature, stirred for 30 min and quenched with EtOAc (40 mL), followed by HCl (5%, 10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ether (3 x 50 mL) and the combined organic phases were washed with brine (20 mL). Solvents were removed in vacuo and the crude product purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with 10~30 % EtOAc in hexanes to afford (3-(ethoxymethoxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methanol (430 mg, 1.85 mmol, 96 %) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR: 7.76 – 7.74 (m, 3H), 7.45 – 7.35 (m, 3H), 5.37 (s, 2H), 4.85 (s, 2H), 3.76 (q, 2H), 2.78 (s, br, 1H, OH),1.26 (t, 3H). 13C NMR: 153.5, 134.1, 131.0, 129.3, 127.4, 126.3, 124.4, 109.0, 93.4, 64.8, 62.1, 15.3. HRMS-ESI [M-H]− calc. for C14H15O3- 231.1027, found 231.0998.

2-(Bromomethyl)-3-(ethoxymethoxy)naphthalene (7)

Br2 (0.09 mL, 1.7 mmol) was added to an ice-cold solution of Ph3P (440 mg, 1.7 mmol) and imidazole (114 mg, 1.7 mmol) in DCM (20 mL) and the mixture stirred for 10 min. A solution of 24 (260 mg, 1.1 mmol) in DCM (40 mL) was added and stirred for 30 min at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was filtered and the precipitate washed with cold 20 % ether in hexane (2 x 5 mL). The combined filtrates were washed with a saturated solution of sodium dithionite (2 x 10 mL), brine (20 mL), and the solvents removed in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with 10 % ether in hexanes to afford 7 (320 mg, 1.08 mmol, 97 %) as a white solid. M.p. = 54 °C. 1H NMR: 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.44 (dd, J = 3.2, 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (m, 2H), 7.36 (dt, J = 1.2, 5.6 Hz,1H), 5.45 (s, 2H), 4.72 (s, 2H), 3.84 (q, 2H), 1.28 (t,3H). 13C NMR: 153.1, 134.9, 130.5, 129.1, 128.1, 127.8, 127.1, 127.1, 124.6, 109.5, 93.3, 64.9, 29.7, 15.4. HRMS-ESI [M+H] calc. for C14H16BrO2+ 295.0328, found 295.0342.

Ethyl 2-[6-(3-(ethoxymethoxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methoxy-3-oxo-3H-xanthen-9-yl]benzoate (8)

Potassium carbonate (0.051 g, 0.37 mmol) was added to a solution of fluorescein ethyl ester 10 (120 mg, 0.33 mmol), and bromide 7 (154 mg, 0.52 mmol) in DMF (5 mL) at r.t. The mixture was stirred for 4 h, quenched with HCl (5 %, 5 mL) and diluted with EtOAc (20 mL). The reaction mixture was washed with saturated NH4Cl (3 x 20 mL) and brine (20 mL). The organic layer was dried with Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with 1% MeOH in CHCl3 to afford ethyl 2-[6-(3-(ethoxymethoxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methoxy-3-oxo-3H-xanthen-9-yl]benzoate (8) (0.19 g, 0.33 mmol, 99 %) as a bright yellow solid. Rf = 0.1, M.p= 124 °C. 1H NMR: 8.25 (dd, J = 1.2, 1.6, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.78 – 7.65 (m, 4H), 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.45 (dt, J = 1.2, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (dt, J = 1.2, 1.6, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (dd, J = 1.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.10(d, J = 2.4 Hz1H), 6.93 – 6.85 (m,3H), 6.54 (dd, J = 2.0, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.44 (d,1H), 5.43 (s, 1H), 5.37(s, 1H), 5.30 (dq, J = 1.6, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.80(q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.27 (t,2H, OEt), 0.95 (t, 3H). 13C NMR: 185.9, 165.6, 163.5, 159.1, 154.4, 152.9, 150.3, 134.4, 132.7, 130.6, 129.2, 128.1, 127.1, 125.8, 124.6, 117.9, 115.3, 114.2, 109.2, 106.0, 101.5, 93.5, 66.6, 64.9, 61.6, 15.4, 13.8. HRMS-ESI calc. for [M+H]; C36H31O7+ 575.2064, found 575.2070

9-(2-(Hydroxymethyl)phenyl)-6-((3-((2-methoxyethoxy)methoxy)naph-thalen-2-yl)methoxy)-3H-xanthen-3-one (9)

A solution of DIBAL-H (5.5 mL, 5.5 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of fluorescein ethyl ester 8 (663 mg, 1.10 mmol) in DCM (15 mL) at –78 °C under argon. The resulting solution was stirred for 10 min and allowed to warm up to r.t. The reaction was quenched with 2 mL of a saturated solution of NH4Cl, and the mixture stirred for 10 min. A solution of DDQ (274 mg, 1.21 mmol) in ether (50 mL) was added and the mixture stirred for another 30 min. The reaction mixture was filtered through a pad of celite, solvents were removed in vacuum, and the crude mixture purified by chromatography (EtOAc/hexanes (1:1)) to afford alcohol 9 (320 mg, 0.57 mmol, 52 %) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR: 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.75 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.46 – 7.31 (m, 4H), 6.95 – 6.71 (m, 5H), 6.59 (s, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 5.45 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 2H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 4.85 (s, 1H), 3.88 (t, 2H), 3.59 (t, 2H), 3.38 (m, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H). 13C NMR: 176.5, 153.5, 152.9, 139.3, 134.3, 134.3, 130.8, 130.1, 129.4, 129.3, 128.5, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 127.8, 127.0, 127.0, 126.6, 126.5, 124.5, 124.5, 109.2, 101.7, 93.8, 93.7, 77.6, 77.2, 76.9, 71.9, 71.8, 68.4, 68.1, 66.2, 62.3, 59.2, 20.8. HRMS calc. for [M+H]; C35H31O7+ 563.2064, found 563.2071.

9-(2-(Hydroxymethyl)phenyl)-6-((3-hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl)methoxy)-3H-xanthen-3-one (4)

Amberlyst-15 resin (100 mg) was added to 9 (100 mg, 0.18 mmol) in 15 mL of aqueous methanol (95/5 v/v). The mixture was stirred at 50 °C and monitored by TLC. After 2 h, the reaction mixture was cooled down and solids removed by filtration. Evaporation of the solvents under reduced pressure provided 4 (50 mg, 0.11 mmol, 60%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): 10.16 (s, 1H), 9.83 (s, 1H), 7.88 (s, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H) 7.69 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.47 – 7.34 (m, 4H), 7.30 – 7.18 (m, 3H), 6.89 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (dd, J = 14.9, 8.4 Hz, 3H), 6.58 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.51 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.41 (s, 1H), 5.23 (s, 4H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): 159.0, 158.0, 153.3, 150.5, 150.4, 145.2, 138.4, 134.0, 129.7, 127.4, 125.6, 123.0, 122.8, 117.5, 108.7, 104.2, 101.6, 70.5, 65.4. HRMS-ESI calc. for [M+H]; C31H23O5+ 475.1540, found 475.1544

Bis-allyl-fluorescein (11)

Allyl bromide (2.60 mL, 30.1 mmol) was added to a solution of fluorescein (2.5 g, 7.52 mmol) and cesium carbonate (6.13 g, 18.81 mmol) in DMF (75 mL). The mixture was stirred at 60 °C overnight, poured into cold water (150 mL), and the allyl ether ester of fluorescein precipitated. The orange precipitate was filtered off, washed with cold water (3 x 50 mL) and dried to afford bis-allyl-fluorescein 11 (2.82 g, 6.84 mmol, 91 %) as a yellow solid, which was recrystallized from CCl4. M.p. = 150—152 °C. Lit.19a 153–155 °C. 1H NMR: 8.86 (d, J = 7.6 Hz 1H), 7.74 (t, J = 7.6, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (t, J = 7.6, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (m,2H), 6.76 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (dd, J = 9.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (d, J = 1.6 Hz 1H), 6.11 – 6.01 (m, 1H), 5.64 – 5.54 (m, 1H), 5.46 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1H ), 5.36 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 5.12 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 5.08 (s, 1H), 4.65 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 4.52 – 4.42 (m, 2H). 13C NMR: 185.9, 165.2, 163.2, 159.1, 154.4, 149.6, 134.6, 132.8, 132.1, 131.4, 131.2, 130.7, 130.2, 129.9, 129.1, 119.4, 118.9, 118.0, 115.2, 113.9, 106.0, 101.4, 69.7, 66.2

6'-allyloxy-fluorescein (12)

A solution of sodium hydroxide (25.5 mL, 25.5 mmol) was added to a solution of 11 (750 mg, 1.82 mmol) in MeOH (40 mL). The mixture was stirred at r.t. for 1 h and MeOH was evaporated. The reaction was neutralized with 25 mL of 1.0 M HCl and extracted with DCM (3 x 20 mL). The organic layer was concentrated in vacuo and the crude product purified by chromatography (40 % EtOAc/hexanes) to give 12 (644 mg, 1.73 mmol, 95 %) as a yellow solid. M.p. 189—190 °C. Lit.24 206—207 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): 10.16 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.75 – 6.67 (m, 2H), 6.64 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (s, 2H), 6.10 – 5.96 (m, 1H), 5.41 (dd, J = 17.3, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 5.28 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): 168.5, 163.8, 159.8, 159.47, 152.4, 151.7, 151.7, 135.6, 133.2, 130.1, 129.0, 128.9, 126.0, 124.6, 123.9, 117.7, 112.7, 112.3, 111.1, 109.4, 104.2, 102.2, 101.6, 82.6, 68.5, 40.2, 39.9, 39.7, 39.5, 39.3, 39.1, 38.9.

3'-(Allyloxy)-6'-((3-(ethoxymethoxy)naphthalen-2-yl)methoxy)-3H-spiro[isobenzofuran-1,9'-xanthen]-3-one (13)

Silver(I)oxide (317 mg, 1.37 mmol) was added to a solution of 12 (300 mg, 0.81 mmol) and 2-(bromomethyl)-3-(ethoxymethoxy)naphthalene 7 (380 mg, 1.29 mmol) in dry benzene (10 mL). THF (2 mL) was added and the mixture refluxed for 16 h. The mixture was allowed to cool, filtered through a thin layer of celite and the celite rinsed with EtOAc (80 mL). The solvents were removed in vacuum and the residue purified by chromatography (25 % acetone/ hexanes) to afford 13 (363 mg, 0.62 mmol, 77 %) as yellowish oil. 1H NMR: 8.03 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (s, 1H), 7.78 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.70 – 7.63 (m, 2H), 7.50 – 7.42 (m, 2H), 7.37(t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19(d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.92(d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.79 – 6.68 (m, 4H), 6.66 – 6.61 (m, 1H), 6.11 – 5.98 (m, 1H), 5.45 – 5.41 (m, 3H), 5.34 – 5.26 (m, 3H), 4.57(d, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.80 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.30 (t, 3H). 13C NMR: 169.6, 160.9, 160.5, 153.4, 153.0, 152.8, 152.7, 135.1, 134.4, 132.9, 129.9, 129.3, 129.2, 128.0, 128.0, 127.1, 127.0, 126.7, 126.9, 125.2, 124.5, 124.2, 118.3, 112.6, 112.4, 111.6, 111.7, 109.2, 102.1, 102.0, 93.5, 83.4, 77.6, 77.2, 76.9, 69.3, 66.3, 64.9, 15.4. HRMS-ESI [M+H] calc. for C37H31O7+ 587.2064; found 587.2068.

3'-(Allyloxy)-6'-((3-hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl)methoxy)-3H-spiro[isobenzo-furan-1,9'-xanthen]-3-one (14)

Amberlyst-15 resin (300 mg) and water (1 mL) were added to a solution of 13 (300 mg, 0.51 mmol) in MeOH (20 mL) and the mixture stirred overnight at 50 °C. Amberlyst was filtered off and the solvents were removed in vacuum to afford crude 14 (201 mg, 0.38 mmol, 74 %) as pale yellow solid, which was used without further purification. M.p. = 92 – 95 °C. 1H NMR (Acetone-d6): 9.11 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (s, 1H), 7.82 – 7.77 (m, 2H), 7.75 – 7.66 (m, 2H), 7.45 – 7.35 (m, 2H), 1.15 – 1.09 (m, 1H), 7.31 – 7.25 (m, 3H), 6.86 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 2H), 2.99 – 2.95 (m, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 6.13 – 6.03 (m, 1H), 5.43 (dd, J = 17.3, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.37 (s, 2H), 5.27 (dd, J = 10.6, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 4.67 – 4.61 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (Acetone-d6): 169.5, 161. 8, 161.4, 154.2, 154.0, 153.4, 153.3, 136.2, 135.6, 134.2, 130.9, 130.1, 130.0, 129.4, 129.2, 128.7, 127.8, 127.5, 127.2, 126.8, 125.5, 125.0, 124.2, 118.0, 113.4, 113.3, 112. 8, 112.7, 110.1, 102.7, 102.7, 102.6, 102.5, 83.4, 69.8, 66.8. HRMS-ESI [M+H] calc for C34H25O6+ 529.1646, found 529.1656.

3-(2-Hydroxyethoxy)benzaldehyde (15).28

K2CO3 (4.53 g, 33 mmol) was added to a solution of 3-hydroxybenzaldehyde (2.0 g, 16.4 mmol) in DMF (20 mL) at r.t., the mixture stirred for 20 min, TBDMS-protected bromoethanol (4.70 g, 19.7 mmol) was added, and the mixture stirred overnight. The reaction was quenched with HCl (5 %, 5 mL) and diluted with EtOAc (20 mL). The reaction mixture was washed with saturated NH4Cl ( 3 x 20 mL) and brine (10 mL). The organic layer was then dried with Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified through a short plug of silica gel to afford 3-(2-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)ethoxy)benzaldehyde (4.20 g, 46%, considering that product contained about 50 % of DMF by NMR) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR 9.95 (s, 1H), 7.45 – 7.36 (m, 3H), 7.18 (dt, J = 6.8, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 3.38 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 0.89 (d, 15H).

Aqueous HF (0.47 mL, 14 mmol) was added to a solution of 3-(2-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)ethoxy)benzaldehyde (2.0 g, 7.1 mmol) in acetonitrile (40 mL) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred and the progress of reaction monitored by TLC. After 15 min, solid NaHCO3 (1.5 g, 14.3 mmol) was added. The solid NaHCO3 was filtered and washed with ether (3 x 5 mL). Solvents were evaporated from combined organic phases and the residue purified by flash chromatography (40 % EtOAc/hexanes) to afford 15 (1.04 g, 6.2 mmol, 87%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR: 9.93 (s, 1H), 7.46 – 7.41 (m, 2H), 7.38 – 7.36 (m, 1H), 7.18 (dt, J = 7.3, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (t, 2H), 3.98 (s-broad, 2H), 2.65 (s-broad, 1H). 13C NMR: 192.2, 159.4, 137.9, 130.3, 124.0, 122.0, 113.1, 77.6, 77.2, 76.9, 69.7, 61.4.

3-(2-Bromoethoxy)benzaldehyde (16).29

Br2 (0.316 mL, 6.14 mmol) was added to an ice-cold solution of Ph3P (1.503 g, 5.73 mmol) and imidazole (418 mg, 6.14 mmol) in DCM (10 mL). The mixture was stirred for 10 min, a solution of 3-(2-hydroxyethoxy) benzaldehyde 15 (680 mg, 4.1 mmol) in DCM (10 mL) was added dropwise, and the reaction mixture stirred at 0 °C for 1 h. The precipitate was separated, washed with ether (2 x 50 mL), and the combined organic layers washed with saturated solution of sodium dithionite (2 x 30 mL), brine (20 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the crude residue purified by chromatography (20% EtOAc in hexanes) to afford 16 (900 mg, 3.9 mmol, 96%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR: 9.97 (s, 1H), 7.50 – 7.43 (m, 2H), 7.40 – 7.35 (m, 2H), 7.22 – 7.18 (m, 1H), 4.35 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.66 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR: 192.0, 162.88, 158. 9, 138.1, 130.4, 124.3, 122.2, 113.2, 77.6, 77.2, 76.9, 68.3, 60.6, 53.6, 34.8, 31.7, 29.0, 22.8, 14.3.

3-(2-Azidoethoxy)benzaldehyde (17)

Sodium azide (461 mg, 7.1 mmol) was added to a solution of 16 (650 mg, 2.8 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) and the mixture stirred at 100 °C overnight. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool to r.t., poured into a saturated solution of ammonium chloride (50 mL), and extracted with DCM (3 x 50 mL). The organic phase was washed with water (3 x 30 mL), brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent removed in vacuo. The crude residue was passed through a short plug of silica gel (hexanes) to afford 17 (370 mg, 2.0 mmol, 71%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR: 9.97 (s, 1H), 7.52 – 7.43 (m, 2H), 7.42 – 7.37 (m, 2H), 7.24 – 7.19 (m, 1H), 4.23 – 4.19 (m, 2H), 3.63 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR: 192.0, 159.0, 138.1, 130.4, 124.3, 122.2, 112.9, 77.6, 77.2, 76.9, 67.4, 50.2. HRMS-ESI [M+H] calc. for C9H10N3O2+ 192.0768, found 192.0760

3-(2-Azidoethoxy)benzaldehyde oxime (18)

Hydroxylamine hydrochloride (191 mg, 2.8 mmol) was added to a solution of 17 (350 mg, 1.8 mmol) and Et3N (0.383 mL, 2.8 mmol) in DCM (10 mL). The mixture was stirred at r.t. for 2 h, and then diluted with water (10 mL). The aqueous layer was then extracted with DCM (3 x 15 mL), the combined organic layers were washed with saturated NaHCO3 (10 mL) and brine (5 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. Purification by chromatography (20 % EtOAc in hexanes) gave 18 (334 mg, 1.6 mmol, 88%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR: 8.71 – 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.17 – 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.36 – 7.30 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.20 – 7.15 (m, 3H), 7.01 – 6.94 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 4.20 – 4.15 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.63 – 3.58 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR: 158.7, 150.4, 133.6, 130.2, 121.0, 117.2, 112.0, 77.6, 77.2, 76.9, 67.2, 50.3. HRMS-ESI [M+H] calc. for C9H11N4O2+ 207.0877, found 207.0874

3-(2-Azidoethoxy)-N-hydroxybenzencarboximidoyl chloride (19)

NCS (194 mg, 1.5 mmol) was added in portions to a solution of oxime 18 (300 mg, 1.5 mmol) in DMF (2 mL). About 1 mL dilute gaseous HCl (from a head space above conc. HCl) was bubbled into the solution to initiate the reaction. After 4 min, the temperature rose to 31° C. In 20 min the temperature dropped to 25°C, and reaction mixture then it was diluted with ether (20 mL). The reaction was quenched with water (5 mL): saturated NH4Cl (10 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was extracted with ether (3 x 10 mL). Combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure to give crude chloride 19 (227 mg, 0.94 mmol, 65%) as a pale yellow oil. 1H NMR: 10.39 – 10.37 (s, 1H), 7.50 – 7.47 (m, 1H), 7.40 (s, 1H), 7.34 – 7.27 (m, 1H), 7.02 – 6.95 (m, 1H), 4.20 – 4.15 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.64 – 3.57 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR: 158.3, 138.5, 134.5, 129.7, 120.6, 117.2, 113.1, 67.7, 67.3, 50.3, 50.2. HRMS-ESI [M+H] calc. for C9H10ClN4O2+ 241.0487, found 241.0487

NQMP-caged fluorescein azide (10)

A solution of TEA (0.04 mL, 0.25 mmol) in DCM (2 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of 14 (90 mg, 0.17 mmol) and 3-(2-Azidoethoxy)-N-hydroxybenzencarboximidoyl chloride (19, 45 mg, 0.19 mmol) in DCM (3.5 mL). The mixture stirred overnight, solvent was removed in vacuo, and the residue purified by chromatography (DCM/EtOAc/hexanes, 2:3:7) to afford 10 (66 mg, 0.090 mmol, 53%) as a pale yellow fluffy solid. M.p. = 92— 93°C. 1H NMR (Acetone-d6): 9.09 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (s, 1H), 7.82 – 7.67 (m, 4H), 7.48 – 7.27 (m, 7H), 7.07 – 7.05 (m, 1H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.91 (s,1H), 6.88 – 6.86 (m, 1H), 6.85 – 6.74 (m, 3H), 5.37 (s, 2H), 5.20 – 5.08 (m, 1H), 4.31 – 4.23 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 4H), 3.71 – 3.65 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 3.64 – 3.36 (m, 2H). 13C NMR: 168.7, 161.0, 160.8, 158.9, 156.4, 153.4, 153.2, 152.6, 134.9, 131.6, 130.1, 129.5, 129.5, 129.2, 129.2, 128.6, 127.0, 126.5, 126.5, 126.0, 112.5, 112.3, 112.0, 98.3, 82.5, 67.4, 66.0, 50.2. HRMS-ESI [M+H] calc. for C43H33N4O8 733.2293, found 733.2292

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank NSF (CHE- 1213789) for the financial support of this project; Christopher D. McNitt for providing a sample of oxadibenzocyclooctyne (ODIBO).

Footnotes

Preparation of bromide 7 is described in the Experimental Section

Supporting Information. Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HR-MS spectra of newly synthesized compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Plenum Press; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]; Banica F-G. Chemical Sensors and Biosensors: Fundamentals and Applications. Wiley; Chichester: 2012. [Google Scholar]; Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate Techniques. Academic Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson I, Spence MTZ, editors. The Molecular Probes Handbook. 11. Life Technologies Corporation; Carlsbad: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadler A, Schultz C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:2408. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Li WH, Zheng G. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2012;11:4601. doi: 10.1039/c2pp05342j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Puliti D, Warther D, Orange C, Specht A, Goeldner M. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:1023. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wysocki LM, Lavis LD. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:752. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Angelides KJ. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4107. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bindal RD, Katzenellenbogen JA. Photochem Photobiol. 1986;43:121. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1986.tb09502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ueno T, Hikita S, Muno D, Sato E, Kanaoka Y, Sekine T. Anal Biochem. 1984;140:63. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Cummings RT, Krafft GA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:65. [Google Scholar]; (h) Krafft GA, Arauzlara JL, Cummings RT, Sutton WR, Ware BR. Biophys J. 1988;53:A198. [Google Scholar]; (i) Krafft GA, Sutton WR, Cummings RT. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:301. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dakin K, Zhao Y, Li WH. Nat Methods. 2005;2:55. doi: 10.1038/nmeth730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Betzig E, Patterson GH, Sougrat R, Lindwasser OW, Olenych S, Bonifacino JS, Davidson MW, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hess HF. Science. 2006;313:1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1127344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hess ST, Giriajan TP, Mason MD. Biophys J. 2006;91:4258. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tonnesen J, Nagerl UV. Exp Neurol. 2013;242:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Cebecauer M, Humpolickova J, Rossy J. Method Enzymol. 2012;505:273. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-388448-0.00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kamiyama D, Huang B. Dev Cell. 2012;23:1103. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Patchornik A, Amit B, Woodward RB. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:6333. [Google Scholar]; (b) Amit B, Zehavi U, Patchornik A. Isr J Chem. 1974;12:103. [Google Scholar]; (c) Amit B, Zehavi U, Patchornik A. J Org Chem. 1974;39:192. [Google Scholar]; (d) Barltrop JA, Plant PJ, Schofiel P. Chem Commun. 1966:822. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) van de Linde S, Wolter S, Sauer M. Aust J Chem. 2011;64:503. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cusido J, Deniz E, Raymo FM. Curr Phys Chem. 2011;1:232. [Google Scholar]; (c) Heilemann M. J Biotechnol. 2010;149:243. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fernandez-Suarez M, Ting AY. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:929. doi: 10.1038/nrm2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Deniz E, Tomasulo M, Cusido J, Yildiz I, Petriella M, Bossi ML, Sortino S, Raymo FM. J Phys Chem C. 2012;116:6058. [Google Scholar]; (f) Guo YM, Chen S, Shetty P, Zheng G, Lin R, Li WH. Nat Methods. 2008;5:835. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Lee H-lD, Lord SJ, Iwanaga S, Zhan K, Xie H, Williams JC, Wang H, Bowman GR, Goley ED, Shapiro L, Twieg RJ, Rao J, Moerner WE. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15099. doi: 10.1021/ja1044192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Li WH, Zheng GJ. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2012;11:460. doi: 10.1039/c2pp05342j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Lord SJ, Conley NR, Lee H-lD, Samuel R, Liu N, Twieg RJ, Moerner WE. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9204. doi: 10.1021/ja802883k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Lippincott-Schwartz J, Snapp E, Kenworthy A. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:444. doi: 10.1038/35073068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lidke DS, Wilson BS. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:566. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Bhattacharyya S, Kulesa PM, Fraser SE. Meth Cell Biol. 2008;87:187. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kozlowski DJ, Weinberg ES. Meth Mol Biol. 2000;135:349. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-685-1:349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kozlowski DJ, Murakami T, Ho RK, Weinberg ES. Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;75:551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Peng P, Wang C, Shi Z, Johns VK, Ma L, Oyer J, Copik A, Igarashia R, Liao Y. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:6671. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41385c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pang SC, Hyun H, Lee S, Jang D, Lee MJ, Kang SH, Ahn KH. Chem Commun. 2012;48:3745. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30738c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kolmakov K, Wurm C, Sednev MV, Bossi ML, Belov VN, Hell SW. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2012;11:522. doi: 10.1039/c1pp05321c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Belov VN, Wurm CA, Boyarskiy VP, Jakobs S, Hell SW. AngewChem Int Ed. 2010;49:3520. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhu MQ, Zhu L, Han JJ, Wu W, Hurst JK, Li ADQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4303. doi: 10.1021/ja0567642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Fukaminato T, Tateyama E, Tamaoki N. Chem Commun. 2012;48:10874. doi: 10.1039/c2cc35889a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lord SJ, Lee HD, Samuel R, Weber R, Liu N, Conley NR, Thompson MA, Twieg RJ, Moerner WE. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:14157. doi: 10.1021/jp907080r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Lukyanov KA, Chudakov DM, Lukyanov S, Verkhusha VV. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:885. doi: 10.1038/nrm1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lippincott-Schwartz J, Patterson GH. Meth Cell Biol. 2008;85:45. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)85003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sakamoto S, Terauchi M, Araki Y, Wada T. Biopolymers. 2013;100(6):773–779. doi: 10.1002/bip.22304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klan P, Solomek T, Bochet C, Blanc A, Givens R, Rubina M, Popik V, Kostikov A, Wirz J. Chem Rev. 2013;113:119. doi: 10.1021/cr300177k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wysocki LM, Grimm JB, Tkachuk AN, Brown TA, Betzig E, Lavis LD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:11206. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Furukawa K, Abe H, Tsuneda S, Ito Y. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:2309. doi: 10.1039/b926100a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lin WY, Long LL, Tan W, Chen BB, Yuan L. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:3914. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Corrie JET, Barth A, Munasinghe VRN, Trentham DR, Hutter MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8546. doi: 10.1021/ja034354c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hellrung B, Kamdzhilov Y, Schworer M, Wirz J. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8934. doi: 10.1021/ja052300s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Il'ichev YV, Schworer MA, Wirz J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4581. doi: 10.1021/ja039071z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Kulikov A, Arumugam S, Popik VV. J Org Chem. 2008;73:7611. doi: 10.1021/jo801302m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kostikov A, Popik VV. J Org Chem. 2009;74:1802. doi: 10.1021/jo802612f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arumugam S, Popik VV. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11892. doi: 10.1021/ja9031924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Ando S, Koide K. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2556. doi: 10.1021/ja108028m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Garner AL, St Croix CM, Pitt BR, Leikauf GD, Ando S, Koide K. Nat Chem. 2009;1:316. doi: 10.1038/nchem.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Garner AL, Song FL, Koide K. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5163. doi: 10.1021/ja808385a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Adamczyk M, Grote J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:807. [Google Scholar]; (b) Krafft GA, Sutton WR, Cummings RT. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:301. [Google Scholar]; (c) Perez GSA, Tsang D, Skene WG. New J Chem. 2007;31:210. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kazarian AA, Smith JA, Hilder EF, Breadmore MC, Quirino JP, Suttil J. Anal Chim Acta. 2010;662:206. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taki M, Iyoshi S, Ojida A, Hamachi I, Yamamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5938. doi: 10.1021/ja100714p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michelot D, Meyer M. Nat Prod Res. 2003;17:41. doi: 10.1080/105763021000027993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Supporting Information

- 24.Corrie JET, Trentham DR. J Chem Soc-Perkin Trans 1. 1995 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundmann C. Fortschr Chem Forsch. 1966;7:62. [Google Scholar]; Feuer H, editor. Nitrile Oxides, Nitrones and Nitronates in Organic Synthesis: Novel Strategies in Synthesis. Wiley; Hoboken: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNitt CD, Popik VV. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:8200. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26581h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brannon JH, Magde D. J Phys Chem. 1978;82:705. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlundt S, Kuzmanich G, Spänig F, Rojas GM, Kovacs C, Garcia-Garibay MA, Guldi DM, Hirsch A. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:12223. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kieran AL, Pascu SI, Jarrosson T, Sanders JKM. Chem Commun. 2005:1276. doi: 10.1039/b417951j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.