Abstract

BACKGROUND

Multidisciplinary care is critical for the successful treatment of Stage III colorectal cancer, yet receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy remains unacceptably low. Peer support, or exposure to others treated for colorectal cancer, has been proposed as a means to improve patient acceptance of cancer care.

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the effect of peer support on colorectal cancer patients’ attitudes toward and adherence to chemotherapy.

DESIGN

We conducted a population-based survey of stage III colorectal cancer patients and compared demographics and adjuvant chemotherapy adherence after patient-reported exposure to peer support.

SETTINGS

Patients were identified using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program cancer registries and recruited 3-12 months after cancer resection.

PATIENTS

All Stage III colorectal cancer patients who underwent colorectal resection between 2011-2013 and located in the Detroit and Georgia regions.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

The main outcome measure was adjuvant chemotherapy adherence. Exposure to peer support was an intermediate outcome.

RESULTS

Among 1,301 patient respondents (68% response rate), 48% reported exposure to peer support. Exposure to peer support was associated with younger age, higher income, and having a spouse or domestic partner. Exposure to peer support was significantly associated with receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (Odds Ratio 2.94, 95% Confidence Interval: 1.89-4.55). Those exposed to peer support reported positive effects on attitudes toward chemotherapy.

LIMITATIONS

This study has limitations inherent to survey research including potential lack of generalizability and responses are subject to recall bias. Additionally, the survey results do not allow for determination of the temporal relationship between peer support exposure and receipt of chemotherapy.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrates that exposure to peer support is associated with higher adjuvant chemotherapy adherence. These data suggest that facilitated peer support programs could positively influence patient expectations and coping with diagnosis and treatment, thereby affecting uptake of postoperative chemotherapy. See Video Abstract at http://links.lww.com/DCR/Axxx.

Keywords: Adherence, Chemotherapy, Colon rectal cancer, Coping, Decision making, Multidisciplinary, Peer support, Socioeconomic status

INTRODUCTION

In spite of clear evidence that stage III colorectal cancer (CRC) patients benefit from postoperative chemotherapy,1 only about 70% of patients receive it according to population-based studies.2–4 Barriers to use of guideline-concordant chemotherapy may be health system- or physician-related factors. For example, only 70% of such patients are seen by a medical oncologist postoperatively,5, 6 and fewer than 75% of those receive the recommended chemotherapy.2 Nonadherence patterns attributed to physicians’ clinical judgment have been associated with patient age, comorbidity, and insurance status.7–9 Other barriers may be patient-related such as concerns over economic status, anxiety or other psychosocial stressors, absence of social support or refusal for unclear reasons.3, 4, 10, 11

Given the multitude of potential patient-related barriers, one approach to improve adherence to chemotherapy recommendations might be to assist patients with establishing realistic expectations. Indeed, previous studies conducted among breast and prostate cancer patients have shown that peer support, or exposure to others who have undergone similar diagnoses and treatment, can improve patient acceptance of and coping with cancer- or cancer treatment-related distress.12 Peer support interventions for such patients have demonstrated improved satisfaction with medical care, enhanced coping skills, and comfort with proposed treatment plans.13–18

However, compared with breast and prostate cancer, colorectal cancer patients experience a host of clinically challenging and socially stigmatized issues, and they lack the sophisticated patient advocacy that has evolved among the other cancer communities.19–21 Furthermore, the specific effect of peer support on colorectal cancer patients’ attitudes toward and adherence to recommended chemotherapy is entirely unknown. We hypothesized that patients who had exposure to peer support would be more adherent to chemotherapy recommendations and investigated the specific causal effects of peer support exposure on patients’ attitudes towards postoperative chemotherapy.

METHODS

Our primary analysis focused on the relationship between exposure to peer support, patient characteristics, and receipt of chemotherapy. We performed a secondary analysis among those exposed to peer support to understand how it affected attitudes toward and coping with chemotherapy.

Study Population

We identified all patients with stage III colon or rectal cancer diagnosed between August 2011 and March 2013 through the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer database of Metropolitan Detroit, Michigan (Oakwood, DeKalb, and Wayne Counties), and the State of Georgia. Patients greater than 21 years old at the time of diagnosis were eligible and recruited within 3 to 12 months after CRC resection. Exclusion criteria included stage IV diagnosis, a change in diagnosis based on final pathology results, residence outside the catchment area, or death prior to survey deployment.

Data Collection

Patients were identified based on pathology reports, and their corresponding physicians were notified about the upcoming survey and invited to opt-out. Patients of the physicians who did not opt-out were then contacted by mail and invited to participate in the survey. A modified Dillman approach was used for recruitment as previously described.22 Once the surveys were returned, extensive data checks for logic, errors, and/or omissions were performed, and patients were contacted to obtain any missing information.

This study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Michigan, Wayne State University, Emory University, the State of Michigan, and the State of Georgia Department of Public Health. All surveys included an information sheet that explained the study purpose, risks and benefits of participation, as well as assurances of maintaining patient confidentiality.

Measures

The primary outcome of the study was receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, based on self-reported data. In comparison to claims data, patient self-report is 98% accurate with respect to use of chemotherapy.23, 24 The primary exposure was peer support, which the survey defined as “support received from another person with colorectal cancer”. In order to confirm reliability in response to receipt of peer support, a second question assessing the same underlying construct (peer support) was asked. Only those with consistent responses of “no peer support” for both questions were defined as such and all responses were consistent between the two questions.

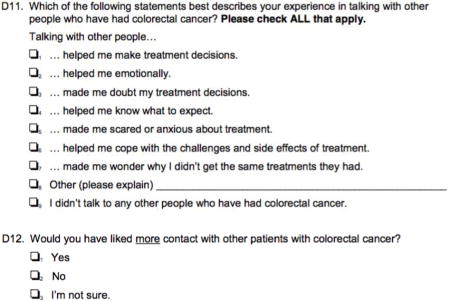

Respondents were asked how much support they received from others with colorectal cancer using a 5-point Likert-response scale, ranging from “None” to “A lot”. Responses were then dichotomized for analytic purposes to “Received” (“A little” to “A lot”) or “Not received” (“None”). Patients were asked to assess the amount or adequacy of support by asking if the amount of peer support had been “Too little,” “Just right” or “Too much”. This was again dichotomized to “Adequate” (“Just right” or “Too much”) or “Inadequate” (“Too little”). Patients were then asked to evaluate how peer support affected their attitudes toward use of chemotherapy. Favorable or positive responses included “it helped me know what to expect”, “it helped me cope with challenges and side effect of treatment”, “it helped me make treatment decisions”, and “it helped me emotionally”. Adverse or negative responses included “it made me doubt my treatment decisions”, “it made me feel anxious about treatment”, and “it made me wonder why I didn’t get the same treatments they had”.

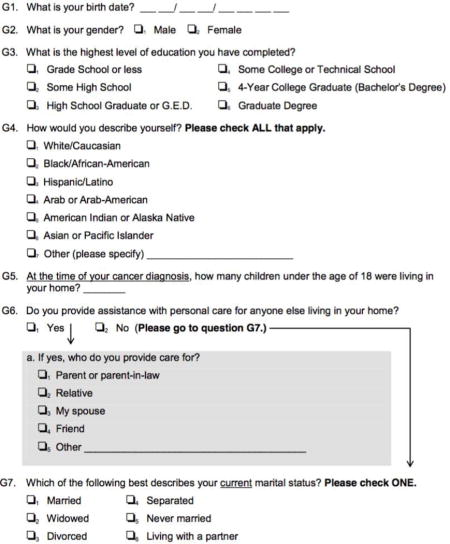

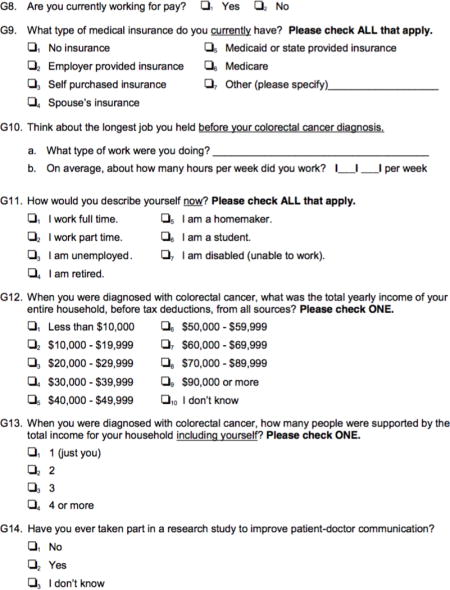

These causal responses were derived from a pilot focus group study followed by testing through cognitive interviews that occurred after survey construction and before deployment. Additional covariates in the survey included self-reported demographics including age at diagnosis, sex, race, marital status, highest level of education, and income.

Statistical Analysis

We identified associations between exposure to peer support, patients’ sociodemographic characteristics and chemotherapy adherence using chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression. In a secondary analysis that included only patients who reported exposure to peer support, we performed multivariable logistic regressions, adjusting for the significant variables found on bivariate analysis, to examine the association between exposure-related attitudes and chemotherapy adherence. All statistical tests were 2-sided and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 software package (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC). Income data was missing for 20% of respondents and was imputed using multiple imputation techniques. All other covariates had less than 1% missing values. Weights were developed to account for patient response rates and included in all multivariate analyses.

RESULTS

Study Sample and Response Rate

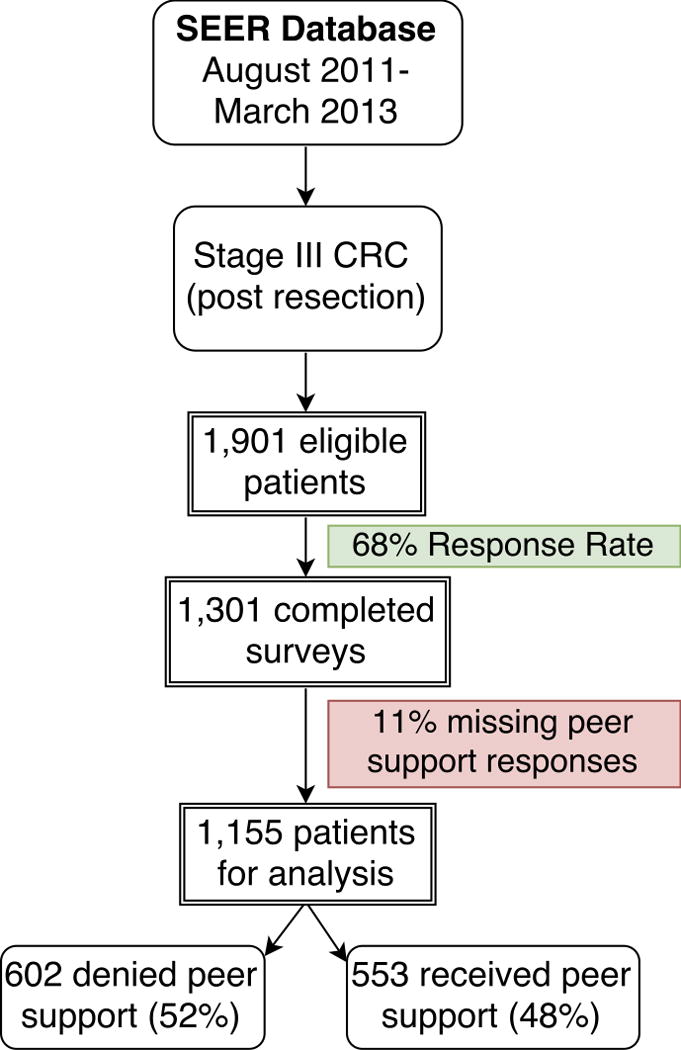

Of the 1,901 eligible patients identified in the SEER registries of Georgia and Metropolitan Detroit, 1,301 completed the survey for a 68% response rate. Six hundred patients (32%) could not be located or did not complete or return the survey. One hundred and forty-six (11%) respondents did not complete the questions regarding peer support exposure and were therefore excluded from analysis. This yielded a total of 1,155 patients for analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survey respondents

Respondent Characteristics and Peer Support

Peer support exposure was reported by 553 (48%) of the respondents; 602 respondents (52%) reported the absence of peer support following diagnosis. Patient characteristics that were statistically significantly associated with peer support included age, marital status, and annual income. Sex, race, and education levels were not associated with exposure to peer support (Table 1).

Table 1.

Respondent Characteristics and receipt of peer support

| Characteristic | Number of Patients (%)

|

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Peer Support N=602 (52) |

Peer Support N=553 (48) |

||

| Age at diagnosis, y | <0.001 | ||

| <50 | 77 (13) | 117 (21) | |

| 50-64 | 202 (33) | 219 (40) | |

| 65-74 | 138 (23) | 130 (23) | |

| 75+ | 185 (31) | 87 (16) | |

| Sex | 0.113 | ||

| Men | 303 (50) | 306 (55) | |

| Women | 295 (49) | 247 (45) | |

| Race | 0.671 | ||

| White | 449 (75) | 400 (72) | |

| Black | 142 (24) | 141 (25) | |

| Other | 11 (2) | 12 (2) | |

| Marital Status | <0.001 | ||

| Not married/partnered | 280 (47) | 188 (34) | |

| Married/partnered | 322 (53) | 365 (66) | |

| Education | 0.457 | ||

| <High School | 90 (15) | 85 (15) | |

| High School | 156 (26) | 122 (22) | |

| Some College | 188 (31) | 183 (33) | |

| ≥College graduate | 159 (26) | 158 (29) | |

| Annual income | 0.003 | ||

| <$20,000 | 103 (17) | 90 (16) | |

| $20,000-$49,999 | 152 (25) | 136 (25) | |

| $50,000-$89,999 | 136 (23) | 122 (22) | |

| ≥$90,000 | 67 (11) | 112 (20) | |

P-values are derived from chi-square tests. Proportions may not add up to 100% because of rounding or missing data

These relationships remained robust in multivariable logistic regression. Patients were more likely to receive peer support if they were younger (<50 years old versus ≥75 years old OR 2.86, 95% CI: 1.85-4.35), married (OR 1.47, 95% CI: 1.09-1.98), or if they had a higher income (≥$90,000 versus <$20,000 OR 1.84, 95% CI: 1.10-3.08). There were no statistically significant associations based on race, sex or education (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of patient characteristics associated with receipt of peer support

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| <50 | Ref. | |

| 50-64 | 0.74 (0.50-1.07) | 0.167 |

| 65-74 | 0.66 (0.44-0.99) | 0.837 |

| 75+ | 0.35 (0.23-0.54) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Men | Ref. | |

| Women | 0.98 (0.76-1.28) | 0.908 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref. | |

| Black | 1.17 (0.85-1.60) | 0.988 |

| Other | 1.34 (0.45-3.94) | 0.699 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Not married/partnered | Ref. | |

| Married/partnered | 1.47 (1.09-1.98) | 0.011 |

| Education | ||

| <High School | 1.26 (0.82-1.92) | 0.116 |

| High School | 0.93 (0.66-1.32) | 0.554 |

| Some College | Ref. | |

| ≥College graduate | 0.85 (0.60-1.19) | 0.191 |

| Annual income | ||

| <$20,000 | Ref. | |

| $20,000-$49,999 | 1.19 (0.82-1.73) | 0.800 |

| $50,000-$89,999 | 1.02 (0.67-1.55) | 0.102 |

| ≥$90,000 | 1.84 (1.10-3.08) | 0.006 |

Peer Support and Chemotherapy Adherence

Patients who reported any peer support overall were more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy than those who reported no peer support (OR 2.94, 95% CI: 1.89-4.55). Comparisons of the patient-reported adequacy of the peer support to lack of peer support demonstrated that there was increased receipt of chemotherapy among those with “Inadequate peer support” but this was not statistically significant after adjustments (OR 1.72, 95% CI: 0.79-3.75). “Adequate peer support”, however, had a statistically significant correlation with increased chemotherapy receipt (OR 2.91, 95% CI: 1.47-5.75) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adequacy of peer support and the likelihood of postoperative chemotherapy adherence

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Receipt of Peer Support | ||

| No Peer Support | Ref. | |

| Peer Support | 2.94 (1.89-4.55) | <0.001 |

| Peer Support Adequacy | ||

| No Peer Support | Ref. | |

| Inadequate Peer Support | 1.72 (0.79-3.75) | 0.982 |

| Adequate Peer Support | 2.91 (1.47-5.75) | 0.013 |

Effects of Peer Support on Attitudes Toward Chemotherapy

A secondary analysis was performed to characterize the specific attitudinal effects of peer support, and the association with chemotherapy adherence. Compared to their counterparts, male respondents (p= 0.006), black respondents (p=0.015), and those who reported an annual income between $20,000 and $49,999 (p=0.001) and had “some college education” (p=0.005) were more likely to indicate that peer support “helped me make treatment decisions.” Black respondents (p=0.006) and those who reported an annual income between $20,000 and $49,999 (p=0.035) were more likely to indicate that peer support “helped me emotionally.” Black respondents (p=0.049) were also more likely to indicate that peer support “helped me know what to expect” with regard to postoperative chemotherapy. Finally, patients who reported an annual income between $20,000 and $49,999 (p=0.031) were more likely to indicate that peer support “made me wonder why I didn’t get the same treatment they had” than those with higher income levels.

Regarding the effects of peer support on attitudes, for the most part, respondents who indicated that peer support was helpful (e.g., “helped me know what to expect” or “helped me cope with the challenges and side effects of treatment”) were more likely to adhere to chemotherapy recommendations than those who did not report these changes (OR 1.70, 95% CI: 1.02-2.84 and OR 5.92, 95% CI: 3.30-10.53, respectively) (Table 4). However, those who reported that peer support “helped me make treatment decisions” (n = 184) were less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy than those who did not report this effect (OR 0.47, 95% CI: 0.26-0.82). Among those who did not receive chemotherapy, 56% reported concern about the associated side effects or complications as reasons for non-adherence.

Table 4.

Patient-reported effects of peer support and adherence to postoperative chemotherapy

| No. of Patients (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talking with other people… | No chemo N=38 |

Chemo N=515 |

p-valuea | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

| …helped me make treatment decisions. | 16 (42) | 168 (33) | 0.231 | 0.47 (0.26-0.82) | 0.008 |

| …helped me emotionally. | 25 (66) | 237 (46) | 0.202 | 1.08 (0.65-1.79) | 0.758 |

| …helped me know what to expect. | 26 (68) | 387 (75) | 0.358 | 5.92 (3.30-10.53) | <0.001 |

| …helped me cope with the challenges and side effects of treatment. | 12 (32) | 381 (74) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.02-2.84) | 0.043 |

| …made me scared or anxious about treatment. | 8 (21) | 50 (10) | 0.028 | 0.56 (0.27-1.16) | 0.118 |

| …made me doubt my treatment decisions. | 2 (5) | 12 (2) | 0.267 | 0.86 (0.25-2.96) | 0.817 |

| …made me wonder why I didn’t get the same treatments they had. | 2 (5) | 20 (4) | 0.675 | 1.64 (0.43-6.21) | 0.468 |

P-values are derived from chi-square tests. Proportions may not add up to 100% because of rounding or missing data

Respondents that indicated adverse effects of peer support exposure (“made me scared or anxious about treatment”, “made me doubt my treatment decisions”, and “made me wonder why I didn’t get the same treatments they had”) were not significantly different from their counterparts in chemotherapy adherence (p=0.12, p=0.82, and p=0.47, respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study of Stage III colorectal cancer patients, respondents who reported any exposure to peers with colorectal cancer were significantly more likely to also report receipt of recommended adjuvant chemotherapy. Additionally, we identified a statistically significant association between the favorable effects of peer support on patients’ attitudes and adherence to recommended therapy. Given that the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colorectal cancer can reduce mortality by up to 33% and recurrence by up to 41%,25 identifying opportunities, such as peer support programs, for improving adherence is critical to improving colorectal cancer outcomes.

Respondents reported that exposure to peer support had a largely favorable effect on their attitudes towards treatment options which may have extended to behaviors. For example, among the 75% of respondents who indicated that it “helped them know what to expect” and the 71% who reported that it “helped them deal with the challenges and side effects of treatment”, we identified a significant increase in chemotherapy adherence. Our findings are consistent with the only other study to our knowledge that investigates the utility of peer support available to CRC patients encompassing 121 patients in Australia. The authors found the key features that patients found useful included information about treatments for CRC, treatment side effects, managing symptoms, and how to be involved in treatment decision-making.26

Regarding the negative effects of peer support, we were surprised to find that patients who described peer support as “helping me make treatment decisions” were actually less likely to adhere to chemotherapy recommendations. We note that the majority of patients who gave this response also reported receiving “inadequate peer support”, which was not significantly associated with chemotherapy adherence. These patients were also more likely to report fear of side effects as a reason for non-adherence. Although there is little to no published literature detailing negative consequences of peer support among cancer patients, reinforcement of negative behaviors and diminished feelings of self-efficacy have been proposed as a possible mechanism.12 The potential for ineffective or adverse peer support therefore highlight the critical? need for structure and training among those providing it in a formal setting.

Our study finding that CRC patients who were younger (<50 years), had a higher income (≥$90,000), or were married were more likely to receive support from peers with colorectal cancer are consistent with prior studies of patients with other types of cancer.2, 3, 13 Taken together, these data may help to define contrasting patient groups that are less likely to receive spontaneous peer support and therefore could derive particular benefit from a structured peer support program. The association between older age and decreased receipt of colorectal cancer chemotherapy in the absence of clinical contra-indications is well established.2 Whether this is a result of clinician bias or patient decision-making is less clear; for example, older patients may refuse chemotherapy due to concern for worsening quality of life.27 Thus, this population may especially benefit from speaking with others who have already been treated with chemotherapy.

We also found that patients with a lower income (<$20,000) were less likely to receive peer support than their more affluent counterparts (≥$90,000). Previous work from our group revealed that patients with lower incomes reported high levels of worry about the financial burden associated with chemotherapy.22 Such a vulnerable subset of patients may be worth targeting by facilitated peer support programs in order to mitigate financial concerns that function as a deterrent to chemotherapy adherence. Although education and income were correlated, we did not identify a significant relationship between education and peer support, nor did we find mediator or moderator variables to explain this phenomenon. It is possible that the resources afforded to those with the highest level of income allowed for additional opportunities to seek peer support.

We also note that respondents who were married or partnered were more likely to report exposure to peer support, which may be attributable to an expanded social network. For married or partnered patients, peer support may add value beyond that available in a domestic relationship. Previous work indicates that peer support, as opposed to other patient support models, provides reassurance from people who have a shared stressful experience and is more likely to be seen as more genuine and helpful than similar sentiments shared by friends or family members without a cancer diagnosis.14, 28

Our study was subject to several limitations inherent to survey research that should be noted. While the survey response rate of 68% was high, it is possible that non-respondents differed from respondents in ways that could affect generalizability. In addition, respondents may have been subject to recall bias. However, this limitation was mitigated by strict adherence to distribution of surveys within four months of surgery (when chemotherapy should have been initiated) and acceptance of completed surveys only up to one year after surgery. Any survey returned after this date was not included in order to limit the possibility of recall bias. Finally, although we explored the self-reported effects of peer support on patient attitudes toward chemotherapy, further evaluation is warranted to clarify whether a causal rather than simply an associative relationship exists between peer support and chemotherapy adherence. Disruptions to this causal pathway could include respondents being exposed to peer support once they had already initiated chemotherapy as they would have increased opportunities for meeting other CRC patients during their treatment sessions. Alternatively, patients could have sought out peer support when having difficulty coping with the side effects of the treatment. That said, we believe the current survey results provide sufficient evidence to warrant further study of such a relationship. As well, we would recommend exploration of perceived differences in the quality of peer support received, a potential temporal relationship between peer support and chemotherapy initiation, and the relative impact of informal versus structured peer support programs. Such research could inform the development of mechanistic model upon which to base structured peer support opportunities for CRC patients.

In conclusion, we found that exposure to peer support was associated with receipt of chemotherapy among Stage III colorectal cancer patients, and that this association may be based upon improved patient attitudes and coping skills related to CRC treatment. We also identified patients with the greatest unmet need for support, who may be most likely to benefit from a targeted intervention. As the first physicians to treat CRC patients, surgeons play a leading role in their multidisciplinary care and often initiate discussions of adjuvant chemotherapy. Moreover, surgeons engender extremely high levels of trust among patients and may be, therefore, the ideal team members to introduce a potential future peer support intervention to improve patient expectations, coping, and adherence to treatment recommendations.29

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ashley Duby, MOA (Department of Surgery, University of Michigan), Kevin Ward, PhD (Department of Epidemiology, Emory University), and Ikuko Kato, PhD (Department of Pathology, Wayne State University) for their assistance in data collection and project support. All were funded by Research Scholar Grant 11-097-01-CPHPS from the American Cancer Society.

Funding: Pasithorn A. Suwanabol is currently funded by the Division of Geriatric and Palliative Medicine at the University of Michigan and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract and Research Foundation of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Joint Research Award. Dr. Morris and the study were supported by Research Scholar Grant 11-097-01-CPHPS from the American Cancer Society. The American Cancer Society played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix 1. Survey questions related to peer support receipt in colorectal cancer patients

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of disclosures to report.

Presentation of work: This work was presented in part as a podium presentation at the Academic Surgical Congress in Las Vegas, Nevada (February 7th-9th, 2017).

Author Contribution:

Arielle E. Kanters, MD, MS – Was involved in all key steps on study/manuscript development including contribution to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript, final approval of manuscript, and is accountable for all aspects of the work.

Arden M. Morris, MD, MPH – Was involved in study design, analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript, final approval of manuscript, and is accountable for all aspects of the work.

Paul H. Abrahamse, MS – Was involved in analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript, final approval of manuscript, and is accountable for all aspects of the work.

Lona Mody, MD, MSc – Was involved in study design and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript, final approval of manuscript, and is accountable for all aspects of the work.

Pasithorn A. Suwanabol, MD, MS – Was involved in study design, analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript, final approval of manuscript, and is accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute and the Office of Medical Applications of Research of the National Institutes of Health. Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer: summary of NIH consensus statement. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991;61:23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chagpar R, Xing Y, Chiang YJ, et al. Adherence to stage-specific treatment guidelines for patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:972–979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Fuchs CS, et al. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for colorectal cancer in a population-based cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1293–1300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becerra AZ, Probst CP, Tejani MA, et al. Opportunity lost: adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer remains underused. Surgery. 2015;158:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin L-M, Dobie SA, Billingsley K, et al. Explaining black-white differences in receipt of recommended colon cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1211–1220. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris AM, Billingsley KG, Hayanga AJ, Matthews B, Baldwin L-M, Birkmeyer JD. Residual treatment disparities after oncology referral for rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:738–744. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, Begg CB. Age and adjuvant chemotherapy use after surgery for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:850–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu CY, Delclos GL, Chan W, Du XL. Assessing the initiation and completion of adjuvant chemotherapy in a large nationwide and population-based cohort of elderly patients with stage-III colon cancer. Med Oncol. 2011;28:1062–1074. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rayson D, Urquhart R, Cox M, Grunfeld E, Porter G. Adherence to clinical practice guidelines for adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in a Canadian province: a population-based analysis. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:253–259. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li P, Li F, Fang Y, et al. Efficacy, compliance and reasons for refusal of postoperative chemotherapy for elderly patients with colorectal cancer: a retrospective chart review and telephone patient questionnaire. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorgensen ML, Young JM, Solomon MJ. Adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: age differences in factors influencing patients’ treatment decisions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:827–834. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S50970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoey LM, Ieropoli SC, White VM, Jefford M. Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(3):315–337. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell HS, Phaneuf MR, Deane K. Cancer peer support programs-do they work? Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helgeson VS, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychol. 1996;15:135–148. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashbury FD, Cameron C, Mercer SL, Fitch M, Nielsen E. One-on-one peer support and quality of life for breast cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;35:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ussher J, Kirsten L, Butow P, Sandoval M. What do cancer support groups provide which other supportive relationships do not? The experience of peer support groups for people with cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2565–2576. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giese-Davis J, Bliss-Isberg C, Carson K, et al. The effect of peer counseling on quality of life following diagnosis of breast cancer: an observational study. Psychooncology. 2006;15:1014–1022. doi: 10.1002/pon.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw BR, McTavish F, Hawkins R, Gustafson DH, Pingree S. Experiences of women with breast cancer: exchanging social support over the CHESS computer network. J Health Commun. 2000;5:135–159. doi: 10.1080/108107300406866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AbiGhannam N, Chilek LA, Koh HE. Three pink decades: breast cancer coverage in magazine advertisements. Health Commun. 2017 doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1278496. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelman RS, Johnson DA. Advocacy in male health: a state society story. Urol Clin North Am. 2012;39:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall N, Birt L, Banks J, et al. Symptom appraisal and healthcare-seeking for symptoms suggestive of colorectal cancer: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008448. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veenstra CM, Regenbogen SE, Hawley ST, et al. A composite measure of personal financial burden among patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Med Care. 2014;52:957–962. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maunsell E, Drolet M, Ouhoummane N, Robert J. Breast cancer survivors accurately reported key treatment and prognostic characteristics. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips KA, Milne RL, Buys S, et al. Agreement between self-reported breast cancer treatment and medical records in a population-based Breast Cancer Family Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4679–4686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al. Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:352–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002083220602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ieropoli SC, White VM, Jefford M, Akkerman D. What models of peer support do people with colorectal cancer prefer? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:455–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newcomb PA, Carbone PP. Cancer treatment and age: patient perspectives. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1580–1584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.19.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowland JH. Developmental stage and adaptation: adult model. In: Holland JC, Rowland JH, editors. Handbook of Psychooncology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. pp. 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regenbogen SE, Veenstra CM, Hawley ST, et al. The effect of complications on the patient-surgeon relationship after colorectal cancer surgery. Surgery. 2014;155:841–850. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]