Abstract

Background

Although sexual dysfunction is common post-HCT, interventions to address sexual function are lacking.

Methods

We conducted a pilot study to assess the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a multimodal intervention to address sexual dysfunction in allogeneic HCT survivors. Transplant clinicians screened HCT survivors ≥3months post-HCT for sexual dysfunction causing distress. Those who screened positive attended monthly visits with a trained transplant clinician who 1) performed an assessment of the causes of sexual dysfunction; 2) educated and empowered the patient to address his/her sexual concerns; and 3) implemented therapeutic interventions targeting the patient’s needs. Feasibility was defined as having 75% of patients who screened positive agreeing to participate and 80% attending at least two intervention visits. We administered the PROMIS Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measure, Functional-Assessment-of-Cancer-Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant, and Hospital-Anxiety-and-Depression-Scale to evaluate sexual function, quality of life (QOL), and mood, respectively, at baseline and six months post-intervention.

Results

33.1% (50/151) of patients screened positive for sexual dysfunction causing distress, and 94.0% (47/50) agreed to participate with 100% attending two intervention visits. Participants reported improvements in satisfaction (P<0.0001), interest in sex (P<0.0001), and orgasm (P<0.0001), erectile function (P<0.0001), vaginal lubrication (P=0.0001), and vaginal discomfort (P=0.0005). At baseline, 32.6% of participants were not sexually active, compared to 6.5% post-intervention (P=0.0005). Participants reported improvement in their QOL (P<0.0001), depression (P=0.0002), and anxiety (P=0.0019).

Conclusions

A multimodal intervention to address sexual dysfunction integrated within the transplant clinic is feasible with encouraging preliminary efficacy for improving sexual function, QOL, and mood in HCT survivors.

Keywords: Supportive care, sexual dysfunction, survivorship care, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, transplant survivors, hematologic malignancies

Introduction

Allogeneic HCT is a potentially curative treatment for many patients with hematologic conditions.1, 2 The use of HCT has increased over the last decade with more than 20,000 transplants performed in the United States each year, of which 40% are in patients younger than 45 years of age.2–4 The number of HCT survivors will likely surpass half a million by 2030 in the United States alone.4 HCT survivors experience a drastic deterioration in their sexual function that persists for many years following HCT. In fact, sexual dysfunction is the most common and persistent complication post-HCT with over 40% of male and 60% of female survivors reporting long-term sexual dysfunction post-transplant.5–8 Moreover, sexual dysfunction is associated with worse quality of life (QOL), relationship dissatisfaction, and psychological distress.9–13 Consequently, the National Institute of Health Late Effects Initiative identified sexual dysfunction as a major concern facing HCT survivors, highlighting the critical need to develop interventions to enhance sexual function in this population.14

Despite the prevalence of sexual dysfunction, interventions to improve sexual function in HCT survivors are lacking.10, 14, 15 Sexual dysfunction often has multiple etiologies including biologic, interpersonal, psychological, and social factors.7, 9, 15–22 Thus, interventions must include a comprehensive assessment and personalized treatment plan to address the diverse sexual health concerns of HCT survivors.14,19,20 However, prior sexual health interventions in other populations typically have addressed either physical or psychological consequences of treatment.10, 23–25 In addition, sexual counseling interventions for other cancer survivors have generally been extremely resource and time intensive, thereby limiting their potential for dissemination.25, 26 Therefore, a personalized approach that addresses the biologic, interpersonal, psychological, and social aspects of sexual dysfunction in HCT survivors in a feasible, patient-centered, and scalable manner within the outpatient oncology setting is critically needed.10, 14, 15

We conducted a single-arm pilot study to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a multimodal intervention to address sexual dysfunction in HCT survivors. We trained transplant clinicians to deliver the intervention to ensure our care model was sustainable and to promote later dissemination.

Methods

Study Procedures

From 09/20/2015 to 01/30/2017, we screened 151 and subsequently enrolled 47 allogeneic HCT recipients at Massachusetts General Hospital (NCT02492100). We chose to utilize a single-arm pilot design as prior research has shown that sexual dysfunction does not resolve with the passage of time without intervention.25, 27 A research assistant screened the weekly transplant clinic schedule to identify potentially eligible patients. The research assistant then informed the transplant clinician that the patient was potentially eligible for this study and inquired about concerns regarding his or her participation. If the clinician had no concerns, the research assistant attached a notification form to the patient’s paper chart upon arrival to the transplant clinic. The form instructed the transplant clinician to screen the patient for sexual dysfunction using the two-items from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) survivorship guideline: 1) do you have problems with sexual function? and 2) are these problems causing you distress? The transplant clinician then offered study participation for those patients who answered both screening questions affirmatively. The research assistant then reviewed the consent form with interested patients, obtaining written informed consent from those who were eligible for the study. Study participants completed baseline self-reported assessments immediately or within 72 hours of providing informed consent. Patients who completed baseline questionnaires were then registered with the Quality Assurance Office for Clinical Trials and scheduled for their first intervention visit. This study was approved by the Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Patients (age ≥ 18 years) with a hematologic malignancy who underwent an allogeneic HCT at least three months prior to study enrollment were eligible to participate. Patients must have screened positive for sexual dysfunction causing distress as noted above and be able to speak English or complete questionnaires with minimal assistance required from an interpreter or family member. We excluded patients with relapsed disease post-HCT and those with significant psychiatric or co-morbid disease that prohibited adherence to study procedures.

Training of the Study Interventionists

Prior to the study start, two transplant clinicians (one female physician and one female advance practice nurse) were trained to deliver the intervention. The Director of the MGH Cancer Center Sexual Health Clinic (D.D.) developed and supervised the training. The interventionists (1) reviewed the existing literature on assessing and treating sexual dysfunction in cancer survivors; (2) participated in a two-hour training with D.D. to develop a systematic approach to assess and address patients’ sexual health concerns; and (3) attended two days in the sexual health clinic with D.D. to obtain clinical experience evaluating and treating patients with sexual dysfunction.

The Multimodal Sexual Dysfunction Intervention

Study participants attended their first intervention visit within one month of enrollment. The intervention entailed monthly visits with the study interventionists who 1) performed an in-depth assessment of the causes of patients’ sexual dysfunction; 2) educated, normalized, and empowered patients to address their sexual health concerns; and 3) implemented therapeutic interventions targeting their specific sexual health needs [supplemental table 1]. The interventionists focused on addressing the causes of sexual dysfunction shown to be prevalent in this population, including hormonal deficiencies, erectile dysfunction, vaginal atrophy, dyspareunia, chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) affecting the genitals, and medication-induced sexual dysfunction. The interventionists performed a gynecological examination for female participants when appropriate to address the causes of their sexual dysfunction. The interventionists also focused on providing psychoeducation to address psychological etiologies for sexual dysfunction including depression, anxiety, body-image concerns, loss of intimacy, and problems with interpersonal relationships and communication. Participants attended at least two and a maximum of six monthly visits during the study period. Participants who reported complete resolution of their sexual dysfunction after two visits were not required to attend additional visits. The first intervention visit was conducted in-person in the outpatient transplant clinic. Subsequent visits could be conducted in-person or over the telephone. The research team made every effort to schedule the intervention visits on the same day as scheduled appointments in the cancer center. Participants with more complicated sexual health concerns were referred to the MGH Sexual Health Clinic for further evaluation. After each encounter, the interventionist documented the topics covered during the visit, as well as the therapies they recommended to address the participants’ sexual health concerns using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).

Study Measures

Participants completed study questionnaires at baseline prior to the intervention and at six months post-intervention.

Patient-Reported Measures

We used the PROMIS Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures to assess male and female sexual function. This well-validated measure includes the following domains: global satisfaction with sex life, interest in sexual activity, orgasm, erectile function (for men), vaginal lubrication (for women), and vaginal discomfort (for women).28 If a participant reports not having sexual activity on a particular domain, their composite score for that domain cannot be calculated and is not evaluable. However, their lack of sexual activity can be reported descriptively.28

We used the 47-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-BMT (FACT-BMT) to assess patients’ QOL.29 The FACT-BMT is comprised of 5 subscales assessing physical, functional, emotional, and social well-being, as well as Bone Marrow Transplant (BMT) specific concerns. A five-point change in the FACT-BMT is considered clinically significant.29, 30

We measured patients’ anxiety and depression symptoms with the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS consists of two subscales assessing anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D), with subscale scores ranging from 0 (no distress) to 21 (maximum distress).31 We also assessed mood using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), a nine-item measure that detects symptoms of major depressive disorder according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV).32

We also conducted exit interviews with 15 participants after they completed their 6-month post-intervention questionnaire to assess 1) their perception of the acceptability and content of the sexual dysfunction intervention; 2) their perception of the intervention efficacy; and 3) the optimal timing for intervention delivery during the survivorship course. We chose participants for the exit interviews randomly while ensuring adequate representation by gender. We reached thematic saturation after conducting 15 exit interviews.

Demographic and Clinical Factors

Participants also completed a baseline demographic questionnaire to indicate their race, gender, relationship status, education, and income. We reviewed patients’ electronic health records to obtain their cancer diagnosis, date of transplant, conditioning regimen intensity, and whether they had chronic GVHD.

Statistical Analysis

We performed statistical analyses using STATA (v9.3). The primary endpoint of the study was feasibility. We chose the sample size for the study based on the feasibility of completing the project during the proposed timeframe and achieving the feasibility endpoint. The proposed intervention was deemed feasible if 1) at least 75% of patients who screened positive for sexual dysfunction causing distress agreed to participate in the study and attended the first scheduled intervention visit; and 2) at least 80% of enrolled participants attended at least two intervention visits. For all analyses, we considered two-sided p-values < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

The secondary endpoints were to evaluate the preliminary efficacy of the intervention by examining change in patient-reported outcomes from baseline to six months. We used the paired T-test to examine the change in sexual function (PROMIS measure domains), QOL (FACT-BMT), and psychological distress (HADS and PHQ-9) from baseline to six months post-intervention. We used the McNemar test to examine the difference in the proportion of participants not sexually active prior to the intervention compared to post-intervention. Only one participant had missing data at six months (due to death from disease relapse), and therefore we did not need to conduct imputations for missing data.

Results

Participants Characteristics

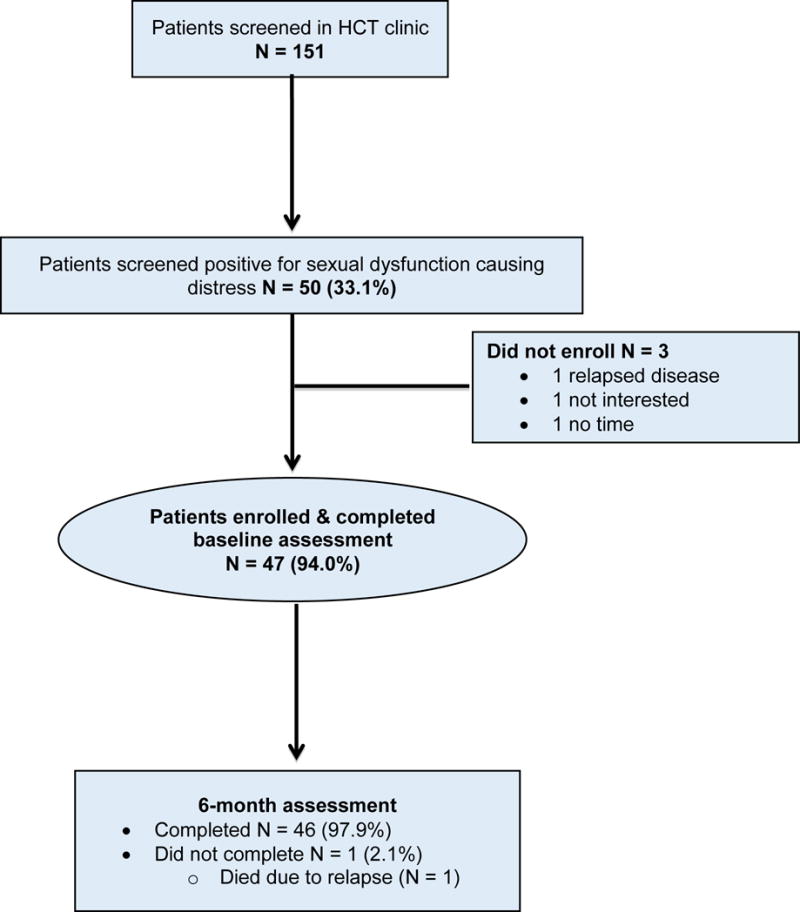

Transplant clinicians systematically screened 151 allogeneic HCT recipients for sexual dysfunction causing distress and identified 50 patients (33.1%) who screened positive. Most patients (47/50, 94.0%) who screened positive agreed to participate and enrolled in the study [Figure 1]. The reasons for non-enrollment were: concern for relapse (n = 1), not interested (n = 1), and lack of time (n = 1). Enrolled participants were mostly White (93.6%) with a median age of 52.5 (range = 24-75) years; and 51.6% were female [Table 1]. The median time from transplant to enrollment was 29 months (range = 3-73). The majority of participants (30/47, 63.8%) had chronic GVHD. All participants completed baseline study assessments. At six months post-intervention, only one patient had missing data due to disease relapse and death.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram.

* HCT= hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Table 1.

Patient Baseline Characteristics: HCT = Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

| Variable | Participants (N = 47) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, median (range) | 52.5 (24-75) |

|

| |

| Female (%) | 24 (51.6%) |

|

| |

| Diagnosis | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 6 (12.8%) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 20 (42.6%) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 4 (8.5%) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 5 (10.6%) |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 6 (12.8%) |

| Other | 5 (10.6%) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| White | 44 (93.6%) |

| Other | 3 (6.4%) |

|

| |

| Relationship status | |

| Married | 34 (72.3%) |

| Divorced | 7 (14.9%) |

| Single | 1 (2.1%) |

| Widowed | 5 (10.6%) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| High school | 7 (14.9%) |

| College | 25 (53.2%) |

| Post graduate | 15 (31.9%) |

|

| |

| Income | |

| <50,000 | 13 (27.7%) |

| 51,000-100,000 | 13 (27.7%) |

| >100,000 | 20 (42.6%) |

| Missing | 1 (2.1%) |

|

| |

| Conditioning intensity | |

| Myeloablative | 22 (46.8%) |

| Reduced intensity | 25 (53.2%) |

|

| |

| Median time in months from transplant to enrollment (range) | 29 (3-173) |

|

| |

| Diagnosis of chronic graft-versus-host disease | 30 (63.8%) |

Feasibility of the Intervention

Overall, 94.0% (47/50) of patients who screened positive for sexual dysfunction causing distress agreed to participate in the study, and all participants attended at least two intervention visits. The median number of visits was 2 with a range of 2-5. The median duration of the first and second visits were 50 minutes (range = 20-120) and 30 minutes (range = 15-90), respectively. The trained transplant nurse practitioner conducted 41.7% of the intervention visits. Approximately half of follow-up intervention visits occurred over the telephone (47.9%, 35/73). Only three participants (6.3%) required referral to the sexual health clinic. The minority of participants (28%, 13/47) had a partner attend an intervention visit.

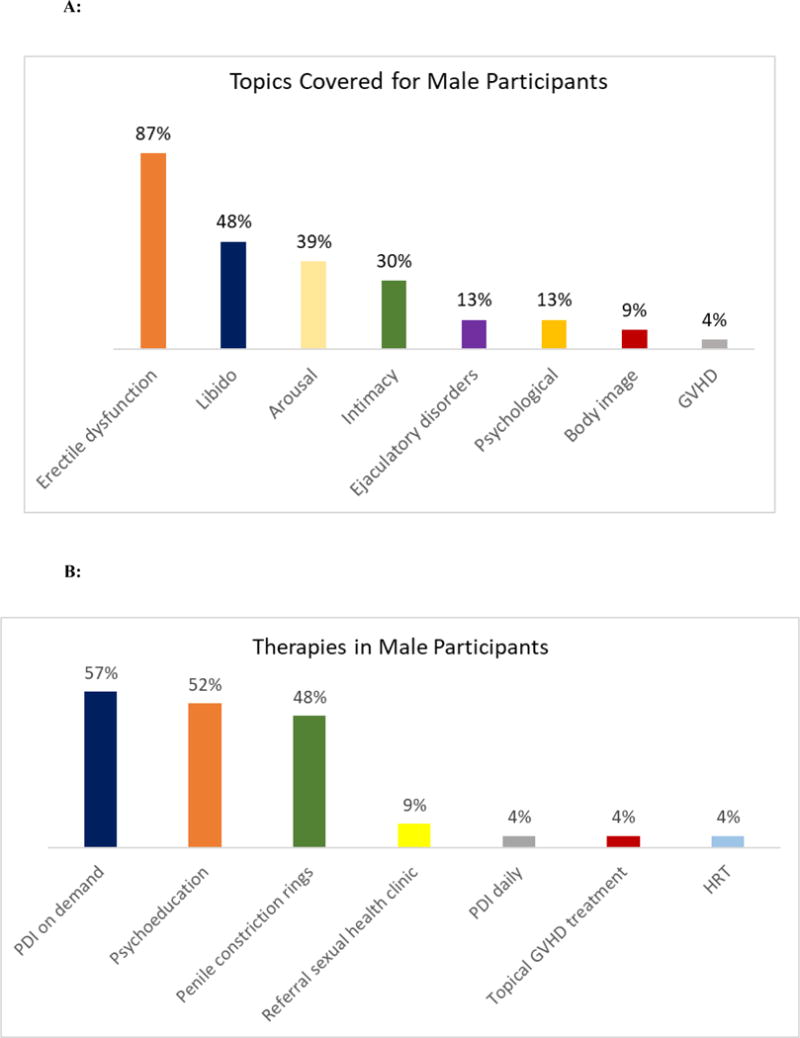

Figure 2 depicts the topics covered during the first intervention visit with male participants (n = 23) and the therapies recommended to address these issues. The most common topics addressed with males were erectile dysfunction (87%), loss of libido (48%), difficulty with arousal (39%), intimacy concerns (30%), ejaculatory disorders (13%), and psychological concerns (13%). The most common therapies recommended for men included phosphodiesterase inhibitors on-demand (57%), psychoeducation and counseling (52%), and penile constriction rings (48%).

Figure 2.

A: Topics discussed during the first intervention visit with male participants: GVHD = graft-versus-host disease

B: Therapies recommended during the first intervention visit for male participants: PDI = Phosphodiesterase inhibitors; GVHD = graft-versus-host disease; HRT = hormone replacement therapy

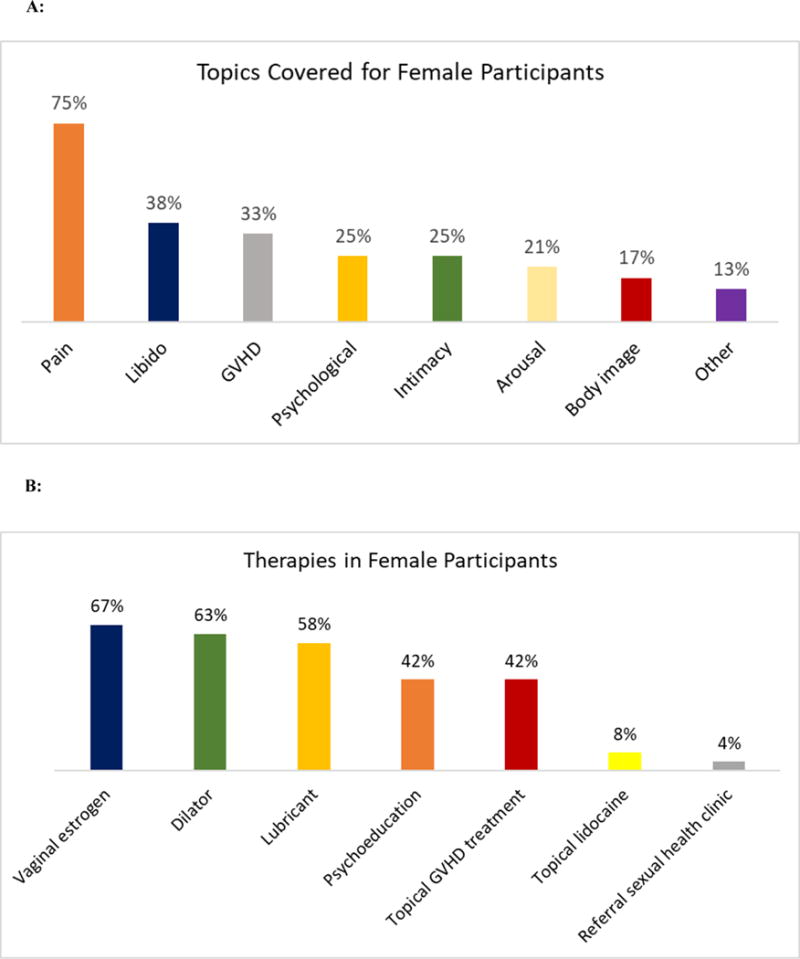

Figure 3 depicts the topics covered during the first intervention visit with female participants (n = 24) and the therapies recommended to address these issues. The most common topics addressed with females were pain with intercourse (75%), loss of libido (38%), GVHD (33%), psychological concerns (25%), intimacy concerns (25%), difficulty with arousal (21%), and body image concerns (17%). The most common therapies recommended for women included vaginal estrogen (67%), dilators (63%), lubricants (58%), psychoeducation and counseling (42%), and topical treatment for GVHD (42%).

Figure 3.

A: Topics discussed during first intervention visit with female participants: GVHD = graft-versus-host disease

B: Therapeutic interventions recommended during first intervention visit for female HCT participants: GVHD = graft-versus-host disease

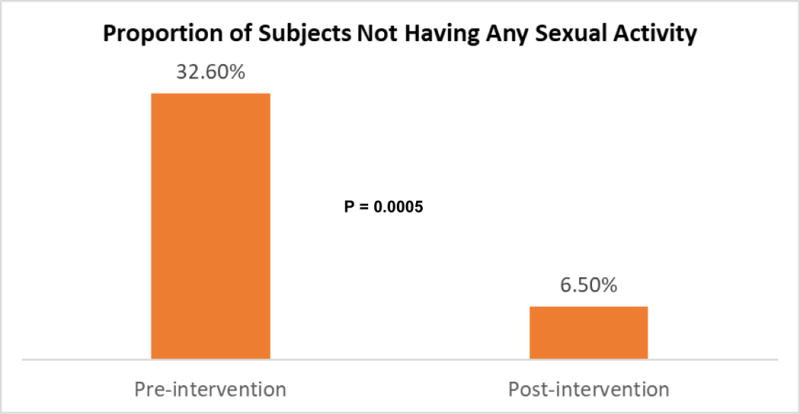

Patient-Reported Sexual Function

At baseline, 32.6% (15/46) of participants were not having sexual activity. Post-intervention, only 6.5% (3/46) of participants were not sexually active (P = 0.0005) [Figure 4]. Participants who were sexually active reported significant improvements in their global satisfaction with sex (P < 0.0001), interest in sex (P < 0.0001), and orgasm (P < 0.0001) [Table 2]. Both male and female participants reported improvement in these outcomes without significant differential effects of the intervention by sex. In addition, male participants also reported a significant improvement in their erectile function post-intervention (P < 0.0001), while female participants reported significant improvements in their vaginal lubrication (P < 0.0001) and vaginal discomfort scores (P = 0.0005).

Figure 4.

Comparison of Proportion of Participants Who were not Sexually Active Pre- and Post-Intervention

Table 2. Effect of the Intervention on Patient-Reported Outcomes.

Some sexual health composite scores (global satisfaction with sex, and orgasm) can only be calculated if a participant reports having sexual activity. Erectile function only measured in male participants; vaginal lubrication and vaginal discomfort only measured in female participants. FACT-BMT = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Bone Marrow Transplant; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9

| Outcomes | Sample Size | Pre-Intervention Mean (SD) |

Post-Intervention Mean (SD) |

Cohen’s d | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global satisfaction with sex | 30 | 16.07 (8.16) | 29.70 (7.51) | 1.34 | <0.0001 |

| Interest in sex | 46 | 10.98 (3.88) | 15.39 (3.69) | 0.91 | <0.0001 |

| Orgasm | 32 | 2.19 (1.31) | 4.22 (1.04) | 1.35 | <0.0001 |

| Erectile function | 19 | 19.58 (7.17) | 32.74 (7.12) | 1.61 | <0.0001 |

| Vaginal lubrication | 16 | 19.44 (13.30) | 34.31 (7.82) | 1.27 | 0.0001 |

| Vaginal discomfort | 13 | 33.77 (15.50) | 14.92 (5.84) | 1.32 | 0.0005 |

| Quality of life (FACT-BMT) | 46 | 107.98 (22.00) | 123.88 (17.10) | 0.81 | <0.0001 |

| Depression (HADS) | 46 | 4.28 (3.10) | 2.33 (2.56) | 0.60 | 0.0002 |

| Anxiety (HADS) | 46 | 4.59 (3.32) | 2.59 (3.11) | 0.49 | 0.0019 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 46 | 4.56 (3.86) | 2.63 (2.58) | 0.45 | 0.0036 |

Patient-Reported QOL and Mood

Participants reported clinically and statistically significant improvements in their QOL (pre-intervention 107.98 vs. post-intervention 123.88, P < 0.0001), as well as symptoms of depression (HADS-D: pre-intervention 4.28 vs. post-intervention 2.33, P = 0.0002; PHQ-9: pre-intervention 4.56 vs. post-intervention 2.63, P = 0.0036), and anxiety (pre-intervention 4.59 vs. 2.59, P = 0.0019) [Table 2].There were no differences in the improvements in patient-reported QOL and mood by sex.

Acceptability of the Intervention

In exit interviews, all participants (15/15) reported that the intervention visits were very convenient as they occurred during their scheduled appointments or via telephone. Participants appreciated the flexibility of having the option of conducting subsequent intervention visits over the telephone. Most participants (14/15) were satisfied with the frequency, timing, and the duration of the intervention visits. Some participants commented that the intervention should be implemented as early as possible post-transplant. All participants reported that the intervention was extremely helpful in addressing their sexual health concerns.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that sexual dysfunction is quite common, affecting approximately one third of allogeneic HCT survivors. We also demonstrated that a multimodal intervention delivered by trained transplant clinicians to address and treat sexual dysfunction in HCT survivors is feasible and acceptable, with promising efficacy. Over 94% of patients who screened positive for sexual dysfunction causing distress agreed to participate in the study, and 100% participated in at least two intervention visits. The intervention led to substantial and clinically significant improvements in patient-reported global satisfaction with sex, interest in sex, orgasm, erectile function, vaginal lubrication, vaginal discomfort, as well as QOL and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Participants found the intervention to be highly acceptable, convenient, and helpful in addressing their sexual health concerns. These encouraging findings warrant further testing in a randomized clinical trial.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which transplant clinicians systematically screened HCT survivors for sexual dysfunction causing distress. Survivors often report that they have no communication with their clinicians about their sexual health concerns.5, 18, 33–36 We showed that transplant clinicians can effectively screen for and talk about sexual dysfunction with their patients during routine clinic visits. Notably, approximately one third of HCT survivors screened positive for sexual dysfunction causing distress, underscoring the frequency of sexual health concerns among HCT survivors. These findings highlight both the importance and feasibility of integrating screening for sexual dysfunction within the routine transplant clinic practice.

Importantly, this intervention was delivered by transplant clinicians with no expertise in sexual health who invested a relatively short amount of time training to address sexual health concerns for HCT survivors. Only three participants required referral for more specialized care, further demonstrating the feasibility of this approach in addressing most sexual health concerns for HCT survivors. This model of care has the potential to be highly sustainable and easily disseminated as oncology clinicians in various practices can be trained to address the sexual health concerns of their patients without the need for more specialized care. These findings are particularly relevant given the lack of specialized clinics to address the sexual health concerns of cancer survivors.6, 19

Our multimodal intervention was shown to be feasible and highly acceptable to HCT survivors. The intervention was delivered and integrated within the outpatient clinic for HCT survivors as they received their routine care. Considering that HCT survivors experience a significant burden coordinating their care and attending multiple outpatient appointments,14 integrating the intervention during routine outpatient transplant care ensures that it is convenient and accessible for this population. We also observed promising preliminary efficacy data of the intervention with significant improvements in all patient-reported outcomes with large effect sizes. To our knowledge, this is the first intervention to demonstrate improvements in all sexual health domains. These results are likely partly due to the personalized and multimodal approach the interventionists utilized to address patients’ sexual health concerns. Experts have strongly recommended utilizing a multimodal approach to address the many etiologies of sexual dysfunction in cancer survivors.10, 14, 15 The intervention also led to remarkable improvements in patient-reported QOL and symptoms of depression and anxiety. These findings highlight the central role sexuality plays in affecting patient QOL and mood.10–13 Studies have shown that sexual dysfunction is associated with relationship discord, intimacy problems, and worse QOL and mood.9–13, 37, 38 Therefore, improving patients’ sexual function post-transplant may have a positive effect on their intimate relationships, thereby enhancing their QOL and physical and psychological health. As many HCT survivors struggle with long-term QOL impairments and psychological distress,39–42 the results are especially noteworthy and warrant further investigation. In future studies, investigators should also explore whether improvement in sexual function mediates the effect of the intervention on QOL and mood in this population.

Our study has several important limitations. First, we had a relatively small sample of mainly white and educated patients who were receiving their care at a single transplant center, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results to other care settings and populations. Second, although the findings of the study are promising, the lack of a control group limits our ability to conclude definitively that improvements in sexual function were not due merely to the passage of time. However, prior research has shown that time alone does not ameliorate sexual dysfunction.25, 27 Nonetheless, randomized controlled trials are needed to demonstrate the efficacy of the multimodal intervention in enhancing sexual function, QOL, and mood in HCT survivors. Third, we do not have long-term follow-up data to assess whether the effects of the intervention on patient-reported outcomes are sustainable. Future studies should include longer-term follow-up assessments of these outcomes.

Our work demonstrates that a multimodal intervention delivered by trained transplant clinicians is feasible and acceptable, with promising preliminary efficacy in improving sexual function, QOL, and mood in HCT survivors. Importantly, we demonstrated that screening for sexual dysfunction can be easily integrated into routine transplant care. Moreover, we successfully trained transplant clinicians to address the majority of sexual health concerns for HCT survivors, thereby testing a highly feasible, accessible, and potentially disseminable model for addressing sexual dysfunction in HCT survivors. A future randomized clinical trial to demonstrate the efficacy of this care model in enhancing sexual function and improving the quality of life and care for HCT survivors is clearly warranted.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1: Content of the Multimodal Sexual Dysfunction Intervention

Condensed Abstract.

Although sexual dysfunction is a common complication affecting HCT survivors, interventions to address sexual function are lacking. A multimodal intervention to address sexual dysfunction integrated within the transplant clinic is feasible with encouraging preliminary efficacy for improving sexual function, QOL, and mood in HCT survivors.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This work was supported by funds from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (El-Jawahri), The Patty Brisben Foundation (El-Jawahri), and K24 CA 181253 (Temel).

Footnotes

Authors Contributions: all authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. All were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All provided final approval of the manuscript and agree to accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of Interest/Financial disclosure: None

References

- 1.Braamse AM, Gerrits MM, van Meijel B, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients treated with auto- and allo-SCT for hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Frauendorfer K, Urbano-Ispizua A. EBMT activity survey 2004 and changes in disease indication over the past 15 years. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:1069–1085. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Aljurf M, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a global perspective. JAMA. 2010;303:1617–1624. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Majhail NS, Tao L, Bredeson C, et al. Prevalence of hematopoietic cell transplant survivors in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1498–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humphreys CT, Tallman B, Altmaier EM, Barnette V. Sexual functioning in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation: a longitudinal study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:491–496. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syrjala KL, Kurland BF, Abrams JR, Sanders JE, Heiman JR. Sexual function changes during the 5 years after high-dose treatment and hematopoietic cell transplantation for malignancy, with case-matched controls at 5 years. Blood. 2008;111:989–996. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syrjala KL, Roth-Roemer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Prevalence and predictors of sexual dysfunction in long-term survivors of marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3148–3157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tierney DK, Palesh O, Johnston L. Sexuality, Menopausal Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Premenopausal Women in the First Year Following Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42:488–497. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.488-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson M, Wheatley K, Harrison GA, et al. Severe adverse impact on sexual functioning and fertility of bone marrow transplantation, either allogeneic or autologous, compared with consolidation chemotherapy alone: analysis of the MRC AML 10 trial. Cancer. 1999;86:1231–1239. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1231::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3712–3719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donovan KA, Thompson LM, Hoffe SE. Sexual function in colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Control. 2010;17:44–51. doi: 10.1177/107327481001700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morreale MK. The impact of cancer on sexual function. Adv Psychosom Med. 2011;31:72–82. doi: 10.1159/000328809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bevans M, El-Jawahri A, Tierney DK, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: The Patient-Centered Outcomes Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thygesen KH, Schjodt I, Jarden M. The impact of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on sexuality: a systematic review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:716–724. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Socie G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Late Effects Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:14–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, Storer BE, Martin PJ. Late effects of hematopoietic cell transplantation among 10-year adult survivors compared with case-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6596–6606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claessens JJ, Beerendonk CC, Schattenberg AV. Quality of life, reproduction and sexuality after stem cell transplantation with partially T-cell-depleted grafts and after conditioning with a regimen including total body irradiation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:831–836. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi JC, Syrjala KL. Sexuality after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer J. 2009;15:57–64. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318198c758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hensel M, Egerer G, Schneeweiss A, Goldschmidt H, Ho AD. Quality of life and rehabilitation in social and professional life after autologous stem cell transplantation. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:209–217. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruner DW, Calvano T. The sexual impact of cancer and cancer treatments in men. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42:555–580; vi. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber CS, Fliege H, Arck PC, Kreuzer KA, Rose M, Klapp BF. Patients with haematological malignancies show a restricted body image focusing on function and emotion. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005;14:155–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brotto LA, Yule M, Breckon E. Psychological interventions for the sexual sequelae of cancer: a review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:346–360. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor S, Harley C, Ziegler L, Brown J, Velikova G. Interventions for sexual problems following treatment for breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:711–724. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Michaud AL, Wright AA. Improvement in sexual function after ovarian cancer: Effects of sexual therapy and rehabilitation after treatment for ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.1002/cncr.30976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hummel SB, van Lankveld J, Oldenburg HSA, et al. Efficacy of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Improving Sexual Functioning of Breast Cancer Survivors: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1328–1340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lubotzky F, Butow P, Nattress K, et al. Facilitating psychosexual adjustment for women undergoing pelvic radiotherapy: pilot of a novel patient psycho-educational resource. Health Expect. 2016;19:1290–1301. doi: 10.1111/hex.12424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM, et al. Development of the NIH PROMIS (R) Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. J Sex Med. 2013;10(Suppl 1):43–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Cella DF, et al. Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) scale. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:357–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al. Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121:951–959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bober SL, Carter J, Falk S. Addressing female sexual function after cancer by internists and primary care providers. J Sex Med. 2013;10(Suppl 1):112–119. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forbat L, White I, Marshall-Lucette S, Kelly D. Discussing the sexual consequences of treatment in radiotherapy and urology consultations with couples affected by prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;109:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammond C, Abrams JR, Syrjala KL. Fertility and risk factors for elevated infertility concern in 10-year hematopoietic cell transplant survivors and case-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3511–3517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendren SK, O’Connor BI, Liu M, et al. Prevalence of male and female sexual dysfunction is high following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:212–223. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171299.43954.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molassiotis A, van den Akker OB, Milligan DW, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of marrow transplantation: comparison with a matched group receiving maintenance chemotherapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vomvas D, Iconomou G, Soubasi E, et al. Assessment of sexual function in patients with cancer undergoing radiotherapy–a single centre prospective study. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:657–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Jawahri AR, Vandusen HB, Traeger LN, et al. Quality of life and mood predict posttraumatic stress disorder after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2016;122:806–812. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pidala J, Anasetti C, Jim H. Quality of life after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;114:7–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prieto JM, Atala J, Blanch J, et al. Patient-rated emotional and physical functioning among hematologic cancer patients during hospitalization for stem-cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:307–314. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Syrjala KL, Chapko MK, Vitaliano PP, Cummings C, Sullivan KM. Recovery after allogeneic marrow transplantation: prospective study of predictors of long-term physical and psychosocial functioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993;11:319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1: Content of the Multimodal Sexual Dysfunction Intervention