Abstract

Acromyrmex leafcutter ants form a mutually beneficial symbiosis with the fungus Leucoagaricus gongylophorus and with Pseudonocardia bacteria. Both are vertically transmitted and actively maintained by the ants. The fungus garden is manured with freshly cut leaves and provides the sole food for the ant larvae, while Pseudonocardia cultures are reared on the ant-cuticle and make antifungal metabolites to help protect the cultivar against disease. If left unchecked, specialized parasitic Escovopsis fungi can overrun the fungus garden and lead to colony collapse. We report that Escovopsis upregulates the production of two specialized metabolites when it infects the cultivar. These compounds inhibit Pseudonocardia and one, shearinine D, also reduces worker behavioral defenses and is ultimately lethal when it accumulates in ant tissues. Our results are consistent with an active evolutionary arms race between Pseudonocardia and Escovopsis, which modifies both bacterial and behavioral defenses such that colony collapse is unavoidable once Escovopsis infections escalate.

Acromyrmex ants cultivate fungus gardens that can be parasitized by Escovopsis sp., leading to colony collapse. Here, Heine et al. identify two secondary metabolites produced by Escovopsis that accumulate in Acromyrmex tissue, reduce behavioural defenses and suppress symbiotic Pseudonocardia bacteria.

Introduction

Ant colonies have nested levels of immune defense encompassing a lower level (individual ants) and a higher collective level that is usually referred to as social immunity1. These social immune defenses are so efficient that specialized epidemic ant diseases are generally unknown2,3. This suggests that essentially no pathogens have been encouraged over evolutionary time to specialize on ants as hosts, except when they could evolve mechanisms to make infected ants leave the protective social immunity of their colonies. Well-known examples are the Ophiocordyceps and Pandora fungi that turn infected ants into zombies and make them die in remote places that are optimal for pathogen spore dispersal4–7. Consistent with this impressive general immune-efficiency, there are no specialized ant diseases known in the attine fungus-farming ants, but their cultivar gardens are plagued by a single specialized fungal parasite Escovopsis8 which arose simultaneously with ant agriculture 55–60 million years ago9.

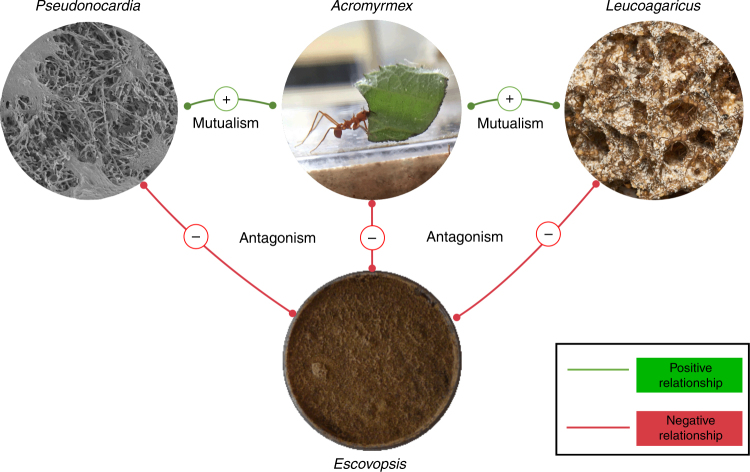

Acromyrmex leafcutter ants form a tripartite superorganismal mutualism with the fungal cultivar Leucoagaricus gongylophorus and a defensive actinobacterial symbiont Pseudonocardia (Fig. 1)10. The cultivar is a functionally polyploid clone11 that the ants provision with freshly cut leaves and carefully groom to remove spores and hyphal growth of Escovopsis and generalist fungal pathogens12. In return for food and housing, the cultivar has evolved specialized hyphal structures, called gongylidia13 which are rich in lipids and sugars. The gongylidia serve two functions: they are the sole food source for the ant larvae but are also ingested by the ant workers to transmit fungal decomposition enzymes to the ant fecal fluid which is deposited on the fresh leaf pulp14. Very early in their evolutionary history, the attine ants started to rear biofilms of antibiotic-producing actinobacteria on their cuticles, which has generally been interpreted as a specialized defense against Escovopsis15. However, these biofilms do not all have Pseudonocardia16 and were not universally maintained over evolutionary time as some attine genera lost the cuticular actinobacteria17,18. The most striking contrast of this kind exists between the two genera of leafcutter ants, where Atta species use phenylacetic acid from their metapleural gland secretions to control Escovopsis17, while Acromyrmex species maintain the cuticular biofilms that are known to reduce the prevalence of Escovopsis12. The same cuticular biofilms may also have sanitation benefits for the ant brood (Fig. 1)16,19–23.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the complex interactions between symbionts of Acromyrmex echinatior leafcutter ants. The ants feed their vertically transmitted bacterial mutualist strain of Pseudonocardia through tiny subcuticular glands and in return the bacteria provide antifungal compounds to kill the parasite Escovopsis. They feed cut leaf fragments to their clonal fungal mutualist Leucoagaricus gongylophorus and this fungus provides the sole food source for their larvae. The parasite Escovopsis also feeds off Leucoagaricus and if left unchecked can overrun and kill the fungal cultivar and the entire ant colony. To prevent this, worker ants groom their fungal cultivar to remove Escovopsis spores and sterilize them with antifungal compounds made by Pseudonocardia. In this work, we show that Escovopsis fights back against the defensive mutualists by producing the virulence factors melinacidin IV (1) and shearinine D (2). Both compounds kill Pseudonocardia and 2 also adversely affects worker ant behavior and is ultimately lethal to the ants. The SEM of Pseudonocardia sp. spores on the surface of A. echinatior ant was taken by Dr. Kim Findlay (JIC); the images of the Acromyrmex ant and fungus garden were taken by Professor Matt Hutchings (UEA); the image of the Escovopsis plate was taken by Dr. Neil Holmes (UEA)

The leafcutter ant symbiosis has been particularly well studied in the Panamanian species Acromyrmex echinatior where the cuticular biofilm is dominated by either Pseudonocardia octospinosus or Pseudonocardia echinatior, two distinct species of actinobacteria with ca. 50/50 population-wide prevalence24,25. These Pseudonocardia species are predicted to make different variants of the broad-spectrum polyene antifungal nystatin26,27, similar to nystatin-like compounds that have been isolated from Pseudonocardia mutualists cultured by Acromyrmex octospinosus ants collected in Trinidad and a basal attine species Apterostigma dentigerum in Costa Rica20,28,29. The Apterostigma mutualist strains also make a cyclic depsipeptide called dentigerumycin which has antifungal activity against Escovopsis30.

It has been estimated that about 50% of A. echinatior nests in Panama are colonized by Escovopsis31 and previous studies have provided largely anecdotal evidence that worker ants die or abandon their gardens when the cultivar is overrun by Escovopsis8. In A. echinatior, such events reflect a failure of the Pseudonocardia biofilm defenses. They occur frequently when colonies are freshly excavated and kept in lab nests where the ants cannot dump their waste away from the garden. The resulting colony collapse suggests that Escovopsis hyphae produce metabolites that affect worker ant behavior and which, at high enough concentrations, are lethal to the ants. However, in unstressed colonies the cuticular Pseudonocardia defenses are highly effective, such that it is usually impossible to isolate Escovopsis from long-term laboratory colonies maintained under optimal conditions. P. octospinosus and P. echinatior also produce a multitude of antibacterial compounds, most likely to defend their position in the cuticular biofilms against secondary infections26,27,32, a metabolic activity that may also explain their general sanitation effects towards ant brood19. These interactions suggest that the Acromyrmex leafcutter ant symbiosis is the result of complex arms races between specialized pathogens and a collective of mutualists33. However, the chemical details of these interactions remain severely understudied.

Here, we identify two secondary metabolites that are upregulated during Escovopsis weberi infection of the fungal cultivar and show that they target the defensive Pseudonocardia mutualists in this system. We report that melinacidin IV (1) and shearinine D (2) are overproduced during infection and both kill the two Pseudonocardia species associated with Panamanian A. echinatior colonies. 2 is a terpene-indole alkaloid closely related to the penitrems which have been linked to the behavioral changes in carpenter ants infected with the Ophiocordyceps ‘zombie ant’ fungus34. We show that ingestion of purified 2 by garden worker ants adversely affects their behavior and is ultimately lethal to the ants. Furthermore, we show that worker ants from fungus gardens artificially or naturally infected with E. weberi contain levels of 2 significantly above those of controls. We sequenced and compared the genomes of five Escovopsis strains isolated from Atta and Acromyrmex leafcutter ant nests with a previously published genome sequence from an Atta-associated strain and found they all encode shearinine-like biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). We hypothesize that shearinines are produced to impede the ability of leafcutter worker ants to efficiently groom and weed their fungus gardens.

Results

Upregulation of Escovopsis virulence factors

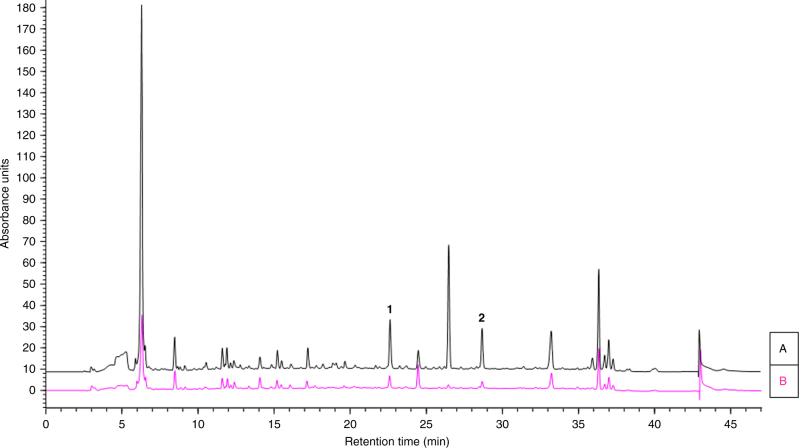

The pathogenesis of Escovopsis on the fungal cultivar L. gongylophorus was studied by co-culturing with E. weberi strain G (Supplementary Table 1) on potato glucose agar (PGA) plates and comparing the secondary metabolome to that of axenic cultures of E. weberi. Chemical profiling of extracts taken from the resulting plates, using ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), revealed the presence of two major, and a range of minor, metabolites produced during pathogenesis. The major metabolites had signals at m/z 729.0937 ([M+H]+) for compound 1 and 600.3340 ([M+H]+) for compound 2 (Fig. 2). Using liquid chromatography (ultraviolet)-mass spectrometry (LC(UV)MS) analysis calibrated using isolated standards (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 2), we confirmed that 1 and 2 were elevated significantly (3.4-fold for 1 and 8.9-fold for 2) when compared to axenic cultures of E. weberi (Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained for the pathogenesis of E. weberi strain A when carried out independently, with upregulation of compounds 1 (2.2-fold) and 2 (2.9-fold) during pathogenesis, and we further confirmed that 1 and 2 were absent in extracts of the healthy food fungus (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Escovopsis pathogenesis involves upregulation of small molecule virulence factors. HPLC profiles (λ = 254 nm) of ethyl acetate extracts of a L. gongylophorus infected with E. weberi strain G; b E. weberi strain G axenic culture. Melinacidin IV, 1; shearinine D, 2

Identification of the Escovopsis virulence factors

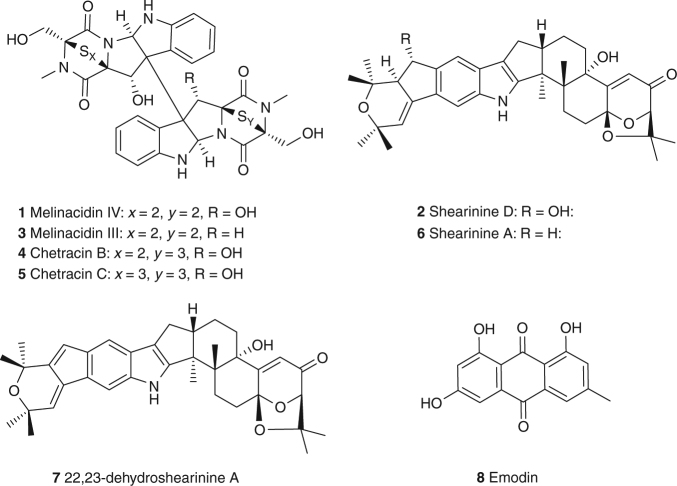

For structure elucidation we isolated 1 and 2 from large-scale axenic cultures of E. weberi strain A grown on PGA plates. Ethyl acetate extraction, silica-based column chromatography and semi-preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) yielded pure samples of 1 (2.0 mg) and 2 (1.4 mg). HRMS analysis of 1 showed an intense M+2 signal, indicating a number of incorporated sulfur atoms. Only half the expected number of signals could be observed in the 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum, indicating a symmetrical compound. Combining these data, a molecular formula of C30H28N6O8S4 was derived. Analysis of 2D NMR data (heteronuclear single-quantum correlation (HSQC) and heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation (HMBC)) pointed to a 1,2-substituted phenyl-ring as part of an indole moiety, while the second part of the molecule was clearly comprised of a diketopiperazine. Comparison of all analytical data, including optical rotation with literature values35, finally confirmed 1 as the epipolythiodiketopiperazine (ETP) antibiotic melinacidin IV, originally isolated from the fungus Acrostalagmus cinnabarinus var. melinacidinus36 (Fig. 3; Supplementary Note 1).

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of the major metabolites produced by Escovopsis strains

The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 showed 4 aromatic protons, 14 aliphatic protons and 24 protons that could be assigned to 8 methyl groups. Further, we determined 16 quaternary carbon atoms, including 1 carbonyl group by analysis of the 13C NMR spectrum. Accordingly, we could assign a molecular formula of C37H45NO6, featuring 16 double bond equivalents. Structure elucidation based on 2D NMR data (HSQC and HMBC) revealed an indole moiety as part of a highly condensed carbon backbone and a Michael acceptor system in proximity to an acetal unit. These features along with the comparison of the chemical shift of all NMR signals with literature data, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) analysis, and the measurement of the optical rotation unambiguously confirmed the identity of 2 as shearinine D, a terpene-indole alkaloid previously isolated from the endophytic fungus Penicillium janthinellum (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 2; Supplementary Note 2)37. Predicted BGCs for terpene-indole alkaloid and ETP metabolites are present in the published E. weberi genome of strain G38 (Supplementary Figs 3 and 4; Supplementary Tables 2-7), and shearinines D, F and J have been identified using imaging mass spectrometry of the Escovopsis strain TZ49 isolated from Trachymyrmex zeteki nests from the same Panamanian field site39. No function was assigned to these compounds in the previous study and the species of Escovopsis was not identified39.

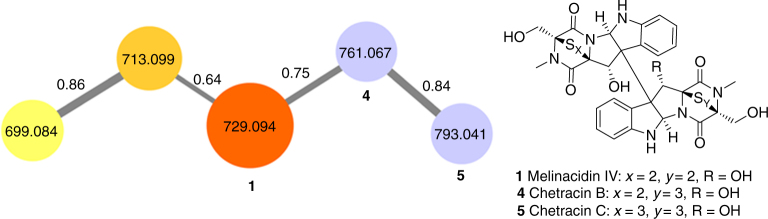

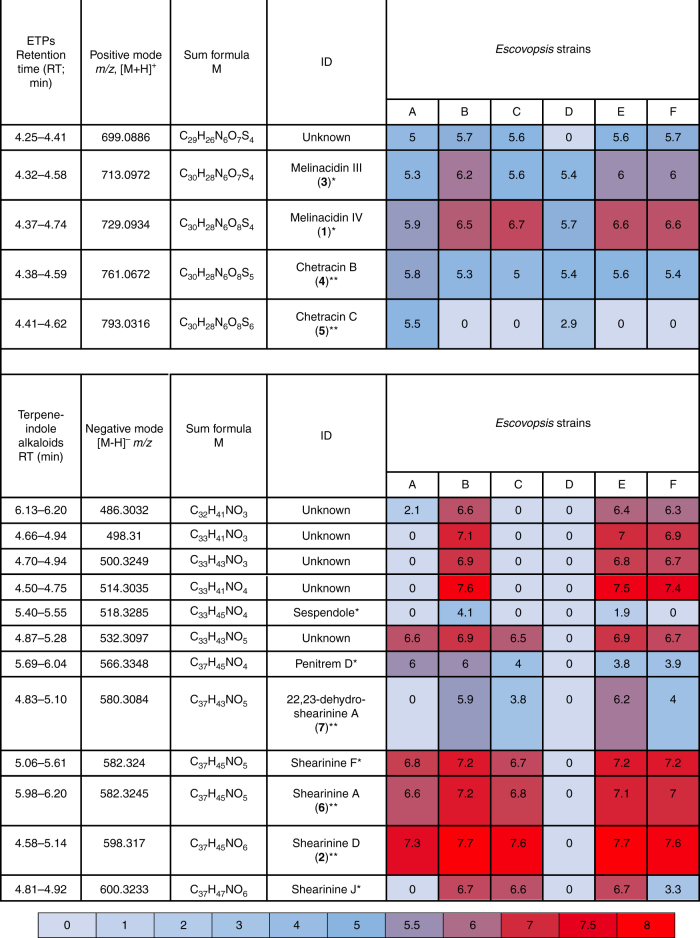

Metabolomics and molecular networking

Having identified two major classes of secondary metabolites upregulated during E. weberi infection of the fungal cultivar, we clarified their distribution among Escovopsis lineages from different attine hosts. We tested five additional Escovopsis strains isolated from the nests of the leafcutter ants Atta colombica (strain C), Acromyrmex echinatior (strains B, E and F), and the higher, non-leafcutter attine Trachymyrmex cornetzi (strain D) (Supplementary Table 1). We cultivated five replicates of each strain, plus strain A as a control, and performed UPLC-MS/MS-based profiling. Data were uploaded to the Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) web platform and used to perform a molecular networking analysis approach40. Molecular networking captures the similarity of analytes by the comparison of their MS/MS spectra and this allowed us to identify a number of metabolite families being produced by the Escovopsis strains (Supplementary Fig. 5). Molecular networking revealed that additional congeners of 1 are present in all six strains (Figs. 4 and 5). We observed compound 3, putatively annotated as melinacidin III (m/z 713.0969 [M+H]+, molecular formula of C30H28N6O7S4; Supplementary Note 3) and a further derivative of melinacidin III, missing one methyl group (m/z 699.0866 [M+H]+, molecular formula of C29H26N6O7S4). Two related signals could be annotated as the ETPs chetracin B (4; m/z 761.0670 [M+H]+, molecular formula of C30H28N6O8S5; Supplementary Note 4) and chetracin C (5; m/z 793.0639 [M+H]+, molecular formula of C30H28N6O8S6; Supplementary Note 5) which was verified by NMR41. ETPs 4 and 5 feature polysulfide bridges of their diketopiperazine moiety of various lengths and are present in lower amounts in the extracts42 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Molecular network and chemical structures of ETPs being produced by Escovopsis strains A–F

Fig. 5.

List of selected signals assigned to ETPs and shearinine-like terpene-indole alkaloid metabolites. Includes a heat map of their average ion count in logarithmic representation. *Metabolite putatively annotated; **metabolite identified and authenticated against isolated sample

We also identified a complex network of shearinine-like terpene-indole alkaloid congeners (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. 6). Production levels were sufficiently high to allow isolation of several compounds from a scaled-up culture of strain C which resulted in 2 (3.5 mg), along with 6 (shearinine A; 1.0 mg) and 7 (22,23-dehydro-shearinine A; 1.8 mg), in addition to the polyketide metabolite emodin (8; 0.85 mg) (Fig. 3). Compound 6 showed an HRMS signal of m/z = 584.3379 corresponding to a molecular formula of C37H45NO5. Comparison of 1H NMR, MS2 data and the retention time of 6 with an authentic reference confirmed its identity as shearinine A (Supplementary Note 6). Compound 7 featured an HRMS signal of m/z = 582.3209 [M+H]+ (corresponding to a molecular formula of C37H43NO5) and could be identified as 22,23-dehydro-shearinine A by the comparison of 1H and 13C NMR data (Supplementary Note 7). Additionally, we observed the presence of likely pathway intermediates such as putative shearinine J and penitrem D (Fig. 5). The discovery of 8 (Supplementary Note 8) as a secondary metabolite produced by an Escovopsis sp. is highly intriguing. Anthraquinones have a long history as a feeding deterrent for ants43–45 and 8 in particular has proven to be a broad-spectrum insecticide comprising activity against three different mosquito species46, the white fly Bemisia tabaci47 and caterpillar larvae48. Analysis of the sequenced genomes (see below) showed that all the Escovopsis strains contain the biosynthetic genes required for production of 8 (Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Tables 8-10).

To determine the distribution and relative levels of the annotated metabolites among the different Escovopsis strains, we used the software Profiling Solutions (Shimadzu) for data analysis, peak picking, data alignment and filtering of metabolic profiling data. A heat map was generated showing the abundance of each ion in the MS profile (Fig. 5). The metabolomics data clearly showed that ETPs are produced by all six Escovopsis strains A–F. In contrast, shearinines are only produced by the five strains isolated from leafcutter ant nests (Atta and Acromyrmex species) but not by Escovopsis isolated from the higher, non-leafcutter attine ant T. cornetzi (strain D) (Fig. 5). We validated our metabolomics data through genome sequencing of strains A–F, which verified that a shearinine-like BGC is present in strains A–C and E–F (Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Tables 2-4); however the BGC was absent from strain D.

Genome sequencing and analysis of Escovopsis strains

To gain deeper insight into the secondary metabolism of the fungal pathogen, we sequenced the genomes of the six Escovopsis strains A–F used in this study. The genome characteristics of these Escovopsis strains are shown in Supplementary Table 1. As a reference, we used the published genome of an E. weberi strain (strain G) isolated from Atta cephalotes collected in Gamboa, Panama; the same field site used to isolate strains A–F and for the collection of ant colonies38. According to Meirelles et al.49, there are nine clades of Escovopsis, with five classified species. Phylogenetic analysis (Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Table 11) using the tef1 gene and internal transcriber spacer (ITS) DNA sequences shows that strains A and C most closely resemble E. weberi species from clade I, and strains B, E and F most closely resemble E. weberi species from clade II. Strain D is distantly related to the E. weberi strains and most closely resembles Escovopsis aspergilloides and aligns to clade VII49. We analyzed all the sequenced Escovopsis genomes using fungiSMASH, an online resource for the rapid identification of natural product BGCs from fungi50. We detected 20–23 putative BGCs for each strain and these mainly comprise terpene, type 1 polyketide synthase and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase clusters. Based on the reported BGC for 2 in P. janthinellum51, we identified homologous BGCs in strains A–C and E–G (Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Tables 2-4). This is consistent with the fact that these strains all make shearinine-like terpene-indole alkaloids, but strain D does not. BGCs for the biosynthesis of ETPs like 1 are present in all seven genomes (Supplementary Fig. 4; Supplementary Tables 5-7) and resemble the BGC responsible for production of the ETP chaetocin from Chaetomium virescens52.

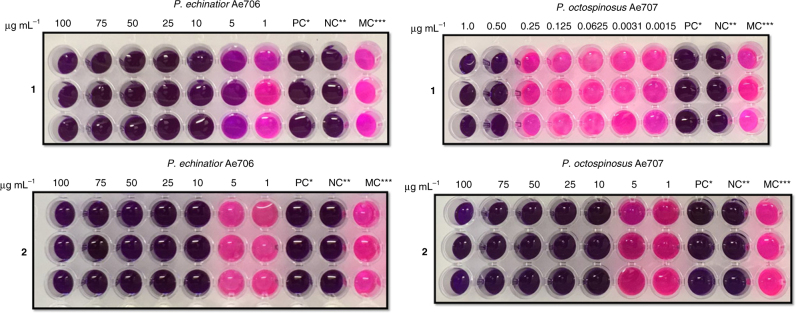

Virulence factors 1 and 2 inhibit Pseudonocardia mutualists

Melinacidins are known to have potent activity against Gram-positive bacteria and we reasoned it would benefit the parasite to inhibit the Pseudonocardia mutualists36. As in some more basal attine branches[16], the Acromyrmex have a tight association with these bacteria as the ants have specialized crypts with small glands for housing and feeding the Pseudonocardia mutualist15. To test our hypothesis, we determined the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of compounds 1 and 2 against representative strains from the two lineages of Pseudonocardia associated with A. echinatior colonies collected in Gamboa, Panama. Strain Ae707 belongs to the Ps1 lineage (P. octospinosus) and strain Ae706 belongs to the Ps2 lineage (P. echinatior)27. Liquid-based colorimetric assays were performed in microtiter plates to determine the MIC. Ciprofloxacin was used as a positive control and all the assays were done in triplicate. The results show that compounds 1 and 2 are active against both tested Pseudonocardia mutualist strains. Compound 1 has an MIC of 10 µg ml−1 against Ae706 and 0.5 µg ml−1 against Ae707, while compound 2 has an MIC of 5 µg ml−1 against both Ae706 and Ae707 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Growth of Pseudonocardia mutualists is inhibited by Escovopsis small molecule virulence factors. Microplate assay of 1 (top) and 2 (bottom) against Pseudonocardia strains Ae706 and Ae707. *PC is the positive control (50 µg ml−1 ciprofloxacin). **NC is the negative control (no inoculation). ***MC, the bacteria grown in LB with 5% of methanol. The pink color indicates viable bacterial cells

Effects of dietary intake of 2 on A. echinatior worker ants

Members of the terpene-indole alkaloid family such as the paspalines53 and the janthitrems54–56 are potent mycotoxins and exhibit insecticidal and tremorgenic activity57. The structurally related penitrems additionally act as feeding deterrents and modulators of ion channels in various insects58–60. The tremorgenic terpene-indole alkaloid 2 has been shown to strongly inhibit the ion channel BKCa, indicating a potent effect on insect nervous systems37. The enhanced production levels of 2 during E. weberi infection of the fungal cultivar suggested that it could be an important feature in the pathogenesis of E. weberi. Even though the pathogen infects the fungal cultivar rather than the ants themselves, we postulated that 2 is a virulence factor primarily affecting the worker ants. Fungal virulence factors are highly diverse but the most well-known example is produced by the fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, which causes infected ‘zombie’ ants to adopt highly unusual behaviors including random walking, repeated convulsions and final death grips underneath leaves5. The identity of the virulence factor(s) is not known but transcriptomics data indicate that O. unilateralis genes with high similarity to those for the biosynthesis of terpene-indole alkaloids such as penitrems, close structural analogs of the shearinines, are upregulated during manipulated biting behavior of infected carpenter ants34.

To characterize the effect of 2 on A. echinatior ants, we established viable sub-populations of five worker ants in a single Petri dish. These were each supplied with a glucose solution supplemented with concentrations of up to 2 mM of 2 dissolved in 50% methanol (Supplementary Fig. 9 Supplementary Movies 1 and 2) or methanol only as a control. After 10 days, the percentage mortality of the worker ants was significantly affected by the concentration of dietary 2 (Supplementary Fig. 10, Kruskall–Wallis test: H = 12.6431DF=3, P = 0.027) with greater levels of mortality occurring at higher concentrations. Survival analysis also demonstrated that the probability of survival over time was significantly reduced at increasing concentrations of 2, even after controlling for different runs of the experiment (Supplementary Fig. 11, Cox’s mixed effects model: hazard ratio = 3.83, z = 0.289, P < 0.001). Supplementation with 50% methanol alone had no effect on ant mortality and all the ants survived the experiment. Additionally, in a control experiment, all ants survived 10 days of exposure to reduced glucose concentrations (dietary concentrations were reduced from 5% to 3% glucose) confirming that mortality was not due to starvation caused by a reduced sugar content at higher concentrations of 2. In addition to the effects on mortality, we also observed reduced mobility, disorientated movement and loss of balance; ants could no longer successfully traverse the sides and lid of the petri dishes as the level of 2 increased. Time-lapse videos showed that mobility decreased as the concentration of 2 increased, and that each ant spent a longer amount of time sitting stationary on the cotton wool. For example, individual ants in the highest concentration treatment group (2 mM) were stationary for a significantly longer period of time compared to the control treatment group; an average ( ± SE) of 62.8 ± 1.74 s out of the total 65 s of film, compared to an average of 8.8 ± 2.1 s in the control group, respectively (t(7.73) = 19.74, P ≤ 0.001, Welch's t-test) (Supplementary Fig. 12, Supplementary Movies 1 and 2).

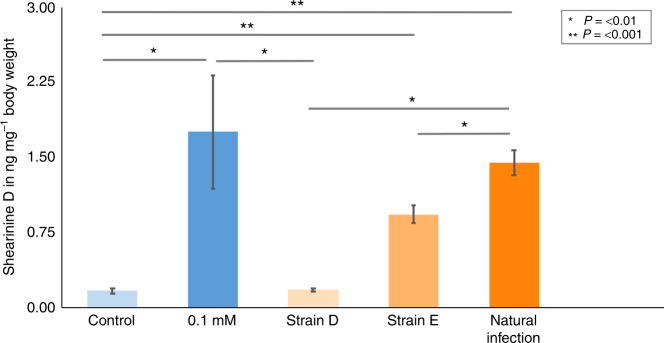

To determine the amount of 2 ingested during these experiments, we developed a multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) MS-based method. An authentic reference of 2 was used along with the internal standard yohimbine to scan for selective MS/MS mass transitions. This confirmed that significantly higher concentrations of 2 are present in the worker ant tissues compared to those in control worker ants (P = 0.001, Dunn’s test) (Fig. 7), and we observed large differences in the tolerated dose of up to 70 ng mg−1 of bodyweight (Supplementary Fig. 13). Effects such as unstable movements and reduced mobility were observed in ants from a minimum level of approximately 10 ng of ingested 2 per mg of bodyweight. We also quantified the levels of 2 in worker ants taken from A. echinatior sub-colony infection experiments, and from ants in a captive A. colombica colony that naturally suffered an uncontrolled outbreak of Escovopsis infection (Fig. 7). This confirmed that ants in infected colonies had ingested large amounts of 2. The levels of 2 in ants during infection with strain E, and also in ants from naturally infected nests, were not significantly different from levels observed in ants that were fed a 5% glucose solution containing 0.1 mM of 2 (Dunn’s test: P = 0.4844 in both cases respectively) (Fig. 7). Worker ants from control colonies fed 5% glucose solution or from colonies infected with strain D isolated from T. cornetzi were indistinguishable (Dunn’ test: P = 0.397), consistent with the lack of shearinine production by strain D (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Accumulation of virulence factor 2 in Acromyrmex ants during nest infection by Escovopsis. Levels of 2 detected in leafcutter worker ants (±s.e.m.) reach biologically relevant concentrations during nest infection by Escovopsis as follows: Acromyrmex echinatior ants fed a 5% glucose solution (control), ants fed a 5% glucose solution containing 0.1 mM 2, and ants from nests artificially infected with Escovopsis strains D or E, as indicated, and Atta colombica ants from a nest with a natural outbreak of Escovopsis (strain unknown). Lines denote significant differences between groups, as confirmed by Dunn’s multiple comparison tests with adjusted P values

Discussion

Two major classes of specialized metabolites are produced during infection of the fungal cultivar L. gongylophorus by the parasitic fungus E. weberi in leafcutter ant nests. Terpene-indole alkaloid 2 is a virulence factor that targets the worker ants and mutualist Pseudonocardia bacteria, while ETPs like 1 target the mutualist bacteria only. Combined results from untargeted metabolomics analysis, molecular networking and genome sequencing indicates the occurrence of ETPs and terpene-indole alkaloids in all six E. weberi strains isolated from the most highly derived attine genera, Atta and Acromyrmex, which comprise the leafcutter ants. We conclude that terpene-indole alkaloids play an important role during the phenomenon of fungus garden collapse in leafcutter ant colonies through the manipulation of worker ant behavior. Impairing the ability of A. echinatior to efficiently remove infected material by grooming their nests increases the chances of E. weberi accelerating chronic low-level infections into acute infestations that will overwhelm entire fungus gardens and allow the parasite to sporulate. This goes some way to explaining previous observations in which fungus gardens are sometimes overwhelmed by E. weberi, resulting in the deaths of worker ants before the fungus garden is destroyed. We also hypothesize that both compounds form part of an arsenal in a microbial battle between E. weberi and the antifungal-producing Pseudonocardia mutualists20,27–30. Our study provides direct evidence of an arms race between this specialized mycoparasite and the defensive actinobacterial mutualists of Acromyrmex leafcutter ants and their domesticated cultivars.

During the process of review for this manuscript, another study was published where the authors identified that an attine-derived Escovopsis strain produces terpene-indole alkaloid shearinines, as well as emodin61.

Methods

Collection of A. echinatior

All ants were sampled from colonies collected during fieldwork in the Gamboa area of the Soberania National Park, Panama (Supplementary Table 1).

Isolation of Escovopsis strains

For strains originating from A. echinatior colonies, Escovopsis was isolated from the waste dumps of lab colonies, or by incubating sections of fungus garden, in Petri dishes with moist cotton wool. Strain identity was verified by PCR amplification and sequencing of the 18S gene using the primer set 18S 1A and 18S 564 (Supplementary Table 12). For strains originating from A. colombica and T. cornetzi colonies, small sections of cultivar fungus were placed on PGA plates under sterile conditions. When viable Escovopsis spores were visible, they were harvested and streaked on to PGA plates under sterile conditions, and then restreaked until pure cultures were obtained. Stocks were made from lawns of each purified Escovopsis strain grown on 25 ml PGA plates. The spores were harvested by applying 2 ml of sterile glycerol solution (20%, v/v) to the surface of the plate and agitating using sterile cotton buds. The spore suspension from each plate was then transferred to a 2 ml screw cap tubes and stored at −80 °C.

Cultivation of E. weberi and isolation of metabolites

Cultivation of E. weberi strain A was performed by streaking spores onto a PGA plate, allowing confluent growth and then spreading from that plate on to 590 new PGA plates using a damp cotton wool bud. PGA was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (the final composition was 4 g l−1 potato extract, 20 g l−1 dextrose and 15 g l−1 agar). After incubation for 33 days at 20 °C the plates were frozen at −80 °C for 2 h, thawed, and the leaking aqueous phase filtered. Residual agar was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 500 ml). The aqueous phase was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 250 ml) and all organic fractions were combined. The organic extract was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel open column chromatography (gradient: n-hexane/ethyl acetate: 4/1 to 0/1). Terpene-indole alkaloids and ETPs were present in the 100% ethyl acetate fraction. Semi-preparative HPLC was used for final purification of metabolites using a Gemini® 5 µm NX-C18 110 Å, 150 × 10.0 mm column (Phenomenex). An elution gradient was used starting from H2O (0.1% formic acid)/MeOH 60/40, to 40/60 within 1 min, to 5/95 within 10 min, to 0/100 within 0.5 min, 0/100 hold for 6.5 min and to 60/40 within 0.5 min.

Co-cultivation of E. weberi strain G and L. gongylophorus

E. weberi was used to infect L. gongylophorus and compared to the axenic culture in three biological replicates. Initially, a plug of 8 mm of L. gongylophorus fungus garden was placed on the edge of a 9 cm diameter petri dish filled with 25 ml of PGA and grown for 5 days at 25 °C. An 8 mm diameter plug taken from a confluent PGA plate of E. weberi strain G was then added on the center of the plate and cocultured with L. gongylophorus for 5 days under the same conditions. The agar was extracted with ethyl acetate (25 ml) and dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate. After filtration, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure from an aliquot (4 ml). The residue was dissolved in methanol (1 ml) for further analysis. Aliquots (15 μl) were analyzed for the content of 1 and 2 as described below.

Quantitative analysis was performed using a Shimadzu Prominence system with LC-20AT pumps, a SIL-20ACHT autosampler and a SPD-M20A PDA detector. Chromatography was achieved using a Nucleodur® C18 HTec, 5 µm, 110 Å, 150 × 10.0 mm column (Macherey-Nagel). A gradient was used starting from H2O (0.1% formic acid)/ACN 99.5/0.5 within 1 min, to 0/100 within 35 min, 0/100 hold for 5 min, and to 99.5/0.5 within 1 min. 1 and 2 showed retention times of 23.2 min and 28.7 min respectively. Quantitative analysis was performed by integrating the areas under the peaks (at 254 nm). Mean area of 1 for the co-culture (n = 3; 34156 ± 4839 au2) and for the axenic culture (n = 3; 10120 ± 4052 au2); mean area of 2 for the co-culture (n = 3; 10504 ± 1798 au2) and for the axenic culture (n = 3; 1175 ± 182 au2). This result confirmed that from a similar experiment which had been run previously and independently in Norwich and which gave similar results (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Spectroscopy

NMR was performed on a Bruker AVANCE III 400 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the solvent residual peak of chloroform-d1 (1H: 7.24 ppm, singlet; 13C: 77.00 ppm, triplet) or DMSO-d6 (1H: 2.50 ppm, quintet; 13C: 39.52 ppm, septet). The Specific optical rotation was measured with a Model 341 Polarimeter (PerkinElmer Inc.). A Lambda 35 UV/Vis spectrometer (PerkinElmer) was used for ultraviolet/visible (UV/Vis) spectroscopy. Unless otherwise mentioned, UPLC-MS measurements were performed on a Nexera X2 liquid chromatograph (LC-30AD) system (Shimadzu) connected to an autosampler (SIL-30AC), a Prominence column oven (CTO-20AC) and a Prominence photo diode array detector (SPD-M20A). The UPLC System was connected to a LCMS-IT-TOF Liquid Chromatograph mass spectrometer (Shimadzu). A Kinetex® 1.7 µm C18 100 Å, 100 × 2.1 mm column (Phenomenex) was used for chromatographic separation and the column oven temperature was set to 30 °C. The mobile phase was a mixture of solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and solvent B (methanol) with a gradient as follows: solvent A/B initial condition 90/10, hold at 90/10 for 1 min, linear gradient up to 0/100 within 9.00 min, hold for 2.00 min, returned to 90/10 within 0.5 min, hold at 90/10 for 0.5 min. MS spectra were acquired within a mass range of m/z 170–1700 using an ion accumulation time of 20 ms per spectrum. We used the following parameters for MS analysis: temperature of the curved desolvation line 250 °C; temperature of the heat block 300 °C; nebulizer gas flow 1.5 l min−1; interface (probe) voltage −3.5 kV for negative mode and 4.5 kV for positive mode. The detector voltage of the time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzer was set to 1.66 kV and the collision-induced dissociation energy to 50%. The instrument was calibrated using sodium trifluoroacetate cluster ions according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Spectra are shown in Supplementary Figs. 14-31.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Lawns of Escovopsis were grown on top of sterilized cellophane discs on PGA medium. After 2 weeks of incubation at room temperature, the fungal mycelium was scrapped off into sterile tubes. Mycelial material was crushed in a pestle and mortar with liquid N2. Crushed freeze-dried material was then used with the QIAGEN DNeasy Plant mini kit to isolate DNA. Illumina sequencing of DNA was carried out at the DNA Sequencing Facility, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, UK, using TruSeq PCR-free and Nextera Mate Pair libraries and a MiSeq 600 sequencer. Genome assembly was performed using Roche Newbler v3.0, scaffolds were polished using PILON version 1.13, and reads were mapped using Burrows–Wheeler transformation version 0.7.12-r1039. BGCs were identified using BLAST 2.2.31+ with amino acid or nucleotide sequences from the published, annotated BGCs.

Sample preparation for MS analysis

Escovopsis strains were grown on PGA medium in five biological replicates for 30 days at 20 °C. Mycelium and agar was disintegrated, transferred into a beaker and extracted with a 1:1 mixture of acetonitrile and methanol (15 ml). The supernatant was filtered, evaporated and the residue dissolved in methanol. Samples were analyzed as described in the Spectroscopy section above.

Molecular networking analysis

UPLC-HRMS chemical profiling data obtained from the Shimadzu IT-TOF system were converted to the mzXML format, uploaded to the GNPS server with FileZilla 3.25.1, and processed using the GNPS web platform. Cytoscape 3.4.0 was used to analyze, organize and visualize data. For the molecular networking analysis we used the following parameters: precursor ion mass tolerance 2.0 Da; fragment ion mass tolerance 0.5 Da; advanced network option: pairs min cosine: 0.5; minimum matched fragment Ions: 2; minimum cluster size: 1; network TopK: 50; maximum connected component size (Beta): 100; advanced library search options: library search min matched peaks: 2; score threshold: 0.7; analog search disabled; maximum analog search mass difference: 100.0; advanced filtering options: filter below Std Dev: 0.0; minimum peak intensity: 0.0; filter precursor window, filter peaks in 50 Da window and filter library.

MIC determination

Stock solutions of 1 and 2 were prepared in methanol and further diluted in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth to give concentration in the range 1.5 ng ml−1 to 100 µg ml−1. Aliquots of each solution (100 µl) were transferred to a 96-well microplate followed by the inoculation of 5 µl of a 1:10 (v/v) 0.5 McFarland suspension of two different Pseudonocardia mutualist strains isolated previously from A. echinatior colonies collected in Gamboa, Panama27. The final concentration of the bacteria was approximately 5 × 104 colony-forming units per ml per well. After 20 h of incubation time at 30 °C and 150 rpm, 5 µl of resazurin solution (6.75 mg ml−1 in deionized water) was added and the color changes were observed prior to 4 h of incubation to determine the MIC. Ciprofloxacin was used as a positive control. To exclude an inhibitory effect of the solvent, control experiments with methanol in LB were performed. All the assays were performed in triplicate.

Dietary supplementation with 2

Purified 2 was dissolved in 50% methanol to give a stock concentration of 5 mM which was diluted with a 5% glucose solution to concentrations of 0.1 mM, 0.25 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM and 2 mM, respectively. Individual A. echinatior worker ants were removed from colonies and placed in 9 cm petri dishes containing a 3 × 2 cm piece of cotton wool soaked in water to maintain humidity. Groups of five ants were supplied with one of the five different concentrations of 2 in 5% glucose (300 µl) or methanol only in 5% glucose (300 µl) as a control for 10 days. In a separate control experiment, ants were exposed to 300 µl of 5, 4.9, 4.75, 4.5, 4 and 3% glucose solutions for 10 days. These reduced concentrations corresponded to the reduced amount of glucose in treatments receiving higher concentrations of compound 2 in the first experiment.

Solutions were supplied to ants in an Eppendorf lid. Water was added to the cotton wool daily and Eppendorf caps were topped up with the respective treatment every 3–4 days. Dead ants in each concentration treatment were scored daily, collected and frozen. Differences in individual motility and the occurrence of unusual movements were monitored by eye via time-lapse videos, which ran over 3 h with 10 s intervals between frames (this amounted to approximately 1 min of video). The amount of time spent stationary by each individual ant was timed (in seconds) between the highest concentration treatment group (2 mM) and the control group, over the course of each time-lapse video. All ants were collected at their time of death or at the end of the 10 days. Samples were immediately frozen at −80 °C and stored until further analysis.

Experimental Escovopsis sub-colony infections

Two separate sub-colonies of A. echinatior were created by taking pieces of fungus garden, measuring approximately 6 cm3, from captive colony Ae088. For each sub-colony, the fungus was placed in a plastic container inside a larger plastic box. Each fungus piece was covered in 20 × 3 µl drops of Escovopsis spore suspension. Spores were prepared by growing confluent Escovopsis lawns on PGA plates and removing spores with a cotton bud and 500 µl of sterile water. Each sub-colony received a different strain of Escovopsis, either strain D (isolated from a Trachymyrmex cornetzi nest) or strain E (isolated from an Acromyrmex echinatior nest). The same number (25 of each caste) of forager and fungus garden worker ants were placed into each sub-colony. The ants were additionally supplied with bramble leaves and cotton wool soaked in water. After 2 weeks, samples of ants, fungus garden and waste dump were taken from sub-colonies and used for chemical analysis.

MS-based quantitation of 1 and 2

Individual A. echinatior ants and samples of L. gongylophorus were stored at −80 °C immediately after collection. To prepare samples for testing, they were warmed to room temperature and their weight determined by a high precision balance. Ants were washed in methanol (for 5 s) to remove potential contamination with 2 on their outer surface. Subsequently, each sample was transferred to a centrifuge tube (15 ml; Corning Incorporated), frozen in liquid nitrogen and mechanically disintegrated by the back end of a disposable spreader. The residue was extracted with 980 µl of methanol. The internal standard, yohimbine (20 µl of a 10 nM solution in methanol), was added. Samples were thoroughly mixed, centrifuged, the supernatant removed, evaporated under reduced pressure and stored at −80 °C. The samples were redissolved in methanol (500 µl) prior to analysis.

Spectra were acquired on a Xevo TQS tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer. We developed a MRM MS method for the quantitation of shearinine natural products featuring at a capillary voltage of 2.00 V; source temperature of 150 °C; desolvation temperature of 500 °C; desolvation gas flow of 800 l h−1; cone gas flow of 150 l h−1; nebulizer pressure of 7 bar; and a collision gas flow of 0.15 ml min−1. For analysis of 2 we optimized the cone voltage (to 30 V) and the collision energies for each of the four transitions (Supplementary Table 13). During parameter optimization, we continuously injected a solution of 2 (0.1 µM in methanol) into a flow of 0.4 ml min−1 of 65% acetonitrile (eluting conditions of the analyte). We used the mass transition 600.4 > 238.2 for quantitation.

For quantitation of 1 we optimized the cone voltage (to 36 V) and the collision energies for each transition (Supplementary Table 13). During parameter optimization, we continuously injected a solution of 1 into a flow of 0.4 ml min−1 of 65% acetonitrile (eluting conditions of 1) into the electrospray ionization source. We used the mass transition 729.1 > 282.1 for quantitation. For the internal standard Yohimbine we again optimized the cone voltage (to 98 V) and the collision energies for each transition (Supplementary Table 13). During parameter optimization, we continuously injected a solution of Yohimbine into a flow of 0.4 ml min−1 of 35% acetonitrile (eluting conditions of the internal standard). We used the mass transition 355.3 > 212.2 (22 V) for quantitation.

Metabolite separation was achieved using an ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters) system and a Kinetex® 1.7 µm C18 100 Å, 50 × 2.1 mm column (Phenomenex). Chromatographic conditions were as follows: starting conditions, H2O (0.1% formic acid)/acetonitrile: 80/20, hold for 0.3 min, up to 30/70 within 1.7 min, up to 0/100 within 1 min, hold for 1.3 min, to 80/20 within 0.1 min, hold for 0.6 min. The total run time was 5 min. A flow rate of 0.4 ml min−1 and a column temperature of 40 °C was used. For each analysis 2 µl of sample was injected using partial-loop needle overfill (PLNO) mode. The weak wash consisted of 500 µl of 10% acetonitrile and 90% water (containing 0.01% formic acid) and the strong wash solution 500 µl consisted of 100% acetonitrile (containing 0.01% formic acid).

Calibration standards were prepared by diluting a stock solution of 1 or 2 (1 mM in methanol) to give calibrants with concentrations of 1 nM, 5 nM, 10 nM, 25 nM, 50 nM, 75 nM, 100 nM, 250 nM, 500 nM, 750 nM and 1 µM. The calibration curve was generated by injecting 2 µl of each standard (PLNO) directly after analysis of the respective samples of each day.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings reported in this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information, or are available from the authors on reasonable request. New nucleotide sequence data have been deposited in NCBI GenBank under the accession codes as follows: E. weberi strain A (NIGB00000000); E. weberi strain B (NQYR00000000); E. weberi strain C (NQYS00000000); Escovopsis strain D (NIGD00000000); E. weberi strain E (NQYQ00000000); E. weberi strain F (NIGC00000000). Raw reads have been deposited at the NCBI Sequencing Reads Archive with accession codes as follows: E. weberi strain A (SRP117677); E. weberi strain B (SRP120297); E. weberi strain C (SRP120188); Escovopsis strain D (SRP136533); E. weberi strain E (SRP122917); E. weberi strain F (SRP117700). Nucleotide sequences and annotations of the BGCs identified in E. weberi strain G are available in the Third Party Annotation Section of the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank databases under the accession numbers TPA: BK010418-BK010420. The ITS sequence for Escovopsis strain D was amplified with ITS1 and ITS4, sequenced and deposited with Genbank accession: MG897412.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grants NE/M015033/1 and NE/M014657/1 from the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) to M.I.H., B.W., J.C.M. and D.W.Y.; by the Biotechnology and Bioscience Research Council (BBSRC) via Institute Strategic Programme Grants BB/J004561/1 and BB/P012523/1 to the John Innes Centre; by the DFG (ChemBioSys, CRC 1127, and Leibniz Prize) to C.H.; and by an Advanced ERC Grant (323085) to J.J.B. which also funded T.M.I., along with a Marie Curie Individual European Fellowship (IEF grant 627949). S.F.W. was funded by a NERC PhD studentship (NERC Doctoral Training Progamme grant NE/L002582/1). The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute provided logistical help and facilities to work in Gamboa, and the Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente yel Mar gave permission to sample and export ants from Panama. We thank the DNA Sequencing Facility, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge UK, especially Dr. Markiyan Samborskyy, for sequencing and assembling the Escovopsis genomes. We also thank Dr. Lionel Hill and Dr. Gerhard Saalbach (Molecular Analysis Services, JIC) for their excellent metabolomics support.

Author contributions

B.W., C.H., P.C.V., D.H., D.W.Y., J.C.M., J.J.B. and M.I.H. designed the research. B.W., D.H., J.J.B., M.I.H., N.A.H. and S.F.W. wrote the manuscript and all authors commented. S.F.W. performed the ant behavioral experiments. T.M.I. isolated the Escovopsis strains B-F from ant waste dumps of colonies maintained in Copenhagen. N.A.H. performed the molecular microbiology experiments, phylogenetics and genome analysis. E.P. maintained captive Atta and Acromyrmex colonies in Norwich. D.H., A.C.A.S. and K.S. isolated metabolites, performed chemical analysis and MIC determination.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Daniel Heine, Neil A. Holmes.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-04520-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Matthew I. Hutchings, Email: m.hutchings@uea.ac.uk

Barrie Wilkinson, Email: barrie.wilkinson@jic.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Cremer S, Sixt M. Analogies in the evolution of individual and social immunity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2009;364:129–142. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boomsma, J. J., Schmid-Hempel, P. & Hughes, W. O. H. in Insect Evolutionary Ecology: Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society’s 22nd Symposium (eds Fellowes, M. D. E., Holloway, G. J., Rolff, J.) Ch. 6, 139–175 (CABI, Wallingford, Reading, 2003).

- 3.Cremer S, Pull CD, Fürst MA. Social Immunity: emergence and evolution of colony-level disease protection. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018;63:105–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-020117-043110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bekker C, et al. Species-specific ant brain manipulation by a specialized fungal parasite. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014;14:166. doi: 10.1186/s12862-014-0166-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes DP, et al. Behavioral mechanisms and morphological symptoms of zombie ants dying from fungal infection. BMC Ecol. 2011;11:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Małagocka J, Jensen AB, Eilenberg J. Pandora formicae, a specialist ant pathogenic fungus: new insights into biology and taxonomy. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017;143:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen SB, et al. The life of a dead ant: the expression of an adaptive extended phenotype. Am. Nat. 2009;174:424–433. doi: 10.1086/603640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currie CR, Mueller UG, Malloch D. The agricultural pathology of ant fungus gardens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:7998–8002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nygaard S, et al. Reciprocal genomic evolution in the ant-fungus agricultural symbiosis. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12233. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Currie CR, Bot A, Boomsma JJ. Experimental evidence of a tripartite mutualism: bacteria protect ant fungus gardens from specialized parasites. Oikos. 2003;101:91–102. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12036.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kooij PW, Aanen DK, Schiott M, Boomsma JJ. Evolutionarily advanced ant farmers rear polyploid fungal crops. J. Evol. Biol. 2015;28:1911–1924. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Currie CR, Stuart AE. Weeding and grooming of pathogens in agriculture by ants. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2001;268:1033–1039. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Fine Licht HH, Boomsma JJ, Tunlid A. Symbiotic adaptations in the fungal cultivar of leaf-cutting ants. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5675. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiøtt M, Rogowska-Wrzesinska A, Roepstorff P, Boomsma JJ. Leaf-cutting ant fungi produce cell wall degrading pectinase complexes reminiscent of phytopathogenic fungi. BMC Biol. 2010;8:156. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currie CR, Poulsen M, Mendenhall J, Boomsma JJ, Billen J. Coevolved crypts and exocrine glands support mutualistic bacteria in fungus-growing ants. Science. 2006;311:81–83. doi: 10.1126/science.1119744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sen R, et al. Generalized antifungal activity and 454-screening of Pseudonocardia and Amycolatopsis bacteria in nests of fungus-growing ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:17805–17810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904827106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández-Marín H, et al. Functional role of phenylacetic acid from metapleural gland secretions in controlling fungal pathogens in evolutionarily derived leaf-cutting ants. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2015;282:20150212. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández-Marín H, et al. Dynamic disease management in Trachymyrmex fungus-growing ants (attini: Formicidae) Am. Nat. 2013;181:517–582. doi: 10.1086/669664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattoso TC, Moreira DDO, Samuels RI. Symbiotic bacteria on the cuticle of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex subterraneus subterraneus protect workers from attack by entomopathogenic fungi. Biol. Lett. 2012;8:461–464. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barke J, et al. A mixed community of actinomycetes produce multiple antibiotics for the fungus farming ant Acromyrmex octospinosus. BMC Biol. 2010;8:109. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kost C, et al. Non-specific association between filamentous bacteria and fungus-growing ants. Naturwissenschaften. 2007;94:821–828. doi: 10.1007/s00114-007-0262-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haeder S, Wirth R, Herz H, Spiteller D. Candicidin-producing Streptomyces support leaf-cutting ants to protect their fungus garden against the pathogenic fungus Escovopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4742–4746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812082106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoenian I, et al. Chemical basis of the synergism and antagonism in microbial communities in the nests of leaf-cutting ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:1955–1960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008441108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen SB, Yek SH, Nash DR, Boomsma JJ. Interaction specificity between leaf-cutting ants and vertically transmitted Pseudonocardia bacteria. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015;15:27. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen SB, Hansen LH, Sapountzis P, Sørensen SJ, Boomsma JJ. Specificity and stability of the Acromyrmex-Pseudonocardia symbiosis. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:4307–4321. doi: 10.1111/mec.12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barke J, Seipke RF, Yu DW, Hutchings MI. A mutualistic microbiome: how do fungus-growing ants select their antibiotic-producing bacteria? Commun. Integr. Biol. 2011;4:41–43. doi: 10.4161/cib.13552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes NA, et al. Genome analysis of two Pseudonocardia phylotypes associated with Acromyrmex leafcutter ants reveals their biosynthetic potential. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:2073. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Arnam EB, et al. Selvamicin, an atypical antifungal polyene from two alternative genomic contexts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:12940–12945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613285113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sit CS, et al. Variable genetic architectures produce virtually identical molecules in bacterial symbionts of fungus-growing ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:13150–13154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515348112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh DC, Poulsen M, Currie CR, Clardy J. Dentigerumycin: a bacterial mediator of an ant-fungus symbiosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:391–393. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reynolds HT, Currie CR. Pathogenicity of Escovopsis weberi: the parasite of the attine ant-microbe symbiosis directly consumes the ant-cultivated fungus. Mycologia. 2004;96:955–959. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2005.11832895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheuring I, Yu DW. How to assemble a beneficial microbiome in three easy steps. Ecol. Lett. 2012;15:1300–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little AEF, Currie CR. Symbiotic complexity: discovery of a fifth symbiont in the attine ant-microbe symbiosis. Biol. Lett. 2007;3:501–504. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bekker C, et al. Gene expression during zombie ant biting behavior reflects the complexity underlying fungal parasitic behavioral manipulation. BMC Genom. 2015;16:620. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1812-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Argoudelis AD, Mizsak SA. Melinacidins II, III and IV. Structural studies. J. Antibiot. 1977;30:468–473. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Argoudelis AD, Reusser F. Melinacidins, a new family of antibiotics. J. Antibiot. 1971;24:383–389. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.24.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu M, et al. Shearinines D–K, new indole triterpenoids from an endophytic Penicillium sp. (strain HKI0459) with blocking activity on large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.10.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Man TJB, et al. Small genome of the fungus Escovopsis weberi, a specialized disease agent of ant agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:3567–3572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518501113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boya P, C A, et al. Imaging mass spectrometry and MS/MS molecular networking reveals chemical interactions among cuticular bacteria and pathogenic fungi associated with fungus-growing ants. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5604. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05515-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang M, et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:828–837. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saito T, et al. Chetracin A and chaetocins B and C, three new epipolythiodioxopiperazines from Chaetomium spp. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988;36:1942–1956. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.1942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, Li D, Luan Y, Gu Q, Zhu T. Cytotoxic metabolites from the Antarctic asychrophilic fungus Oidiodendron truncatum. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:920–927. doi: 10.1021/np3000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blum, M. S. & Hilker, M. in Chemoecology of Insect Eggs and Egg Deposition (eds Hiliker, M & Meiners, T.) Ch. 3, 61–90 (Blackwell, Oxford, 2003).

- 44.Pankewitz F, Hilker M. Defensive components in insect eggs: are anthraquinones produced during egg development? J. Chem. Ecol. 2006;32:2067–2072. doi: 10.1007/s10886-006-9129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeLiberto ST, Werner SJ. Review of anthraquinone applications for pest management and agricultural crop protection. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2016;72:1813–1825. doi: 10.1002/ps.4330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang YC, Lim MY, Lee HS. Emodin isolated from Cassiaobtusifolia (Leguminosae) seed shows larvicidal activity against three mosquito species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:7629–7631. doi: 10.1021/jf034727t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Georges K, Jayaprakasam B, Dalavoy SS, Nair MG. Pest-managing activities of plant extracts and anthraquinones from Cassia nigricans from Burkina Faso. Bioresour. Technol. 2008;99:2037–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trial H, Dimond JB. Emodin in buckthorn: a feeding deterrent to phytophagous insects. Can. Entomol. 1979;111:207–212. doi: 10.4039/Ent111207-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meirelles LA, et al. Shared Escovopsis parasites between leaf-cutting and non-leaf-cutting ants in the higher attine fungus-growing ant symbiosis. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015;2:150257. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber T, et al. antiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nicholson M, et al. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of gene clusters for the biosynthesis of indole-diterpenes in Penicillium crustosum and P. janthinellum. Toxins. 2015;7:2701–2722. doi: 10.3390/toxins7082701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gerken T, Walsh CT. Cloning and sequencing of the chaetocin biosynthetic gene cluster. Chembiochem. 2013;14:2256–2258. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gallagher RT, et al. Paspalinine, a tremorgenic metabolite from Claviceps paspali. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:235–238. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)71177-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Penn J, et al. Janthitrems B and C, two principal indole-diterpenoids produced by Penicillium janthinellum. Phytochemistry. 1993;32:1431–1434. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85153-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Jesus AE, Steyn PS, van Heerden FR, Vleggaar R. Structure elucidation of the janthitrems, novel tremorgenic mycotoxins from Penicillium janthinellum. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1984;10:697–701. doi: 10.1039/p19840000697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lauren DR, Gallagher RT. High-performance liquid chromatography of the janthitrems: fluorescent tremorgenic mycotoxins produced by Penicillium janthinellum. J. Chromatogr. A. 1982;248:150–154. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)83747-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staub GM, Gloer KB, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT, Dowd PF. New paspalinine derivatives with antiinsectan activity from the sclerotia of Aspergillus nomius. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:2569–2572. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77627-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sings H, Singh S. Tremorgenic and nontremorgenic 2,3-fused indole diterpenoids. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. 2003;60:51–163. doi: 10.1016/S0099-9598(03)60002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saikia S, Nicholson MJ, Young C, Parker EJ, Scott B. The genetic basis for indole-diterpene chemical diversity in filamentous fungi. Mycol. Res. 2008;112:184–199. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barry Scott, D. & Parker, E. in Handbook of Industrial Mycology (ed Zhiqiang, A.) Ch. 14, 405–426 (CRC Press, New York, 2010).

- 61.Dhodary B, Schilg M, Wirth R, Spiteller D. Secondary metabolites from Escovopsis weberi and their role in attacking the garden fungus of leaf cutting ants. Chem. Eur. J. 2018;24:4445–4452. doi: 10.1002/chem.201706071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings reported in this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information, or are available from the authors on reasonable request. New nucleotide sequence data have been deposited in NCBI GenBank under the accession codes as follows: E. weberi strain A (NIGB00000000); E. weberi strain B (NQYR00000000); E. weberi strain C (NQYS00000000); Escovopsis strain D (NIGD00000000); E. weberi strain E (NQYQ00000000); E. weberi strain F (NIGC00000000). Raw reads have been deposited at the NCBI Sequencing Reads Archive with accession codes as follows: E. weberi strain A (SRP117677); E. weberi strain B (SRP120297); E. weberi strain C (SRP120188); Escovopsis strain D (SRP136533); E. weberi strain E (SRP122917); E. weberi strain F (SRP117700). Nucleotide sequences and annotations of the BGCs identified in E. weberi strain G are available in the Third Party Annotation Section of the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank databases under the accession numbers TPA: BK010418-BK010420. The ITS sequence for Escovopsis strain D was amplified with ITS1 and ITS4, sequenced and deposited with Genbank accession: MG897412.