Abstract

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), which serve as important and powerful regulators of various biological activities, have gained widespread attention in recent years. Emerging evidence has shown that some lncRNAs play important regulatory roles in osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy for bone fracture. As a recently identified lncRNA, linc-ROR was reported to mediate the reprogramming ability of differentiated cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) self-renewal. However, other functions of linc-ROR remain elusive. In this study, linc-ROR was found to be upregulated during osteogenesis of human bone-marrow-derived MSCs. Ectopic expression of linc-ROR significantly accelerated, whereas knockdown of linc-ROR suppressed, osteoblast differentiation. Using bioinformatic prediction and luciferase reporter assays, we demonstrated that linc-ROR functioned as a microRNA (miRNA) sponge for miR-138 and miR-145, both of which were negative regulators of osteogenesis. Further investigations revealed that linc-ROR antagonized the functions of these two miRNAs and led to the de-repression of their shared target ZEB2, which eventually activated Wnt/β-catenin pathway and hence potentiated osteogenesis. Taken together, linc-ROR modulated osteoblast differentiation by acting as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA), which may shed light on the functional characterization of lncRNAs in coordinating osteogenesis.

Keywords: linc-ROR, ceRNA, mesenchymal stem cells, osteogenesis

Introduction

Bone homeostasis is modulated by the balance between osteoblasts production and osteoclasts destruction in bone tissues.1 As a major constitute of bone tissue, the proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization of osteoblast is very crucial for bone regeneration and microenvironment homeostasis.2 A disorder of osteoblasts would eventually lead to a number of bone diseases such as osteoporosis and osteogenesis imperfecta.3, 4 Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are considered a promising cell therapy for their well-characterized self-renewal potential and trans-differentiation capabilities.5 Therefore, improving the osteoblast differentiation of human MSCs (hMSCs) could be helpful to develop therapeutic strategy for bone diseases.

In recent years, long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been identified as novel regulators of various biological activities and play critical roles in a variety of disease progressions.6 lncRNA could regulate target gene expression by transcription regulation, transcription interference, chromatin modification, microRNA (miRNA) splicing, as well as miRNA sponge by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA).7 Until now, there were many studies about the lncRNA-mediated osteogenic differentiation. The expression profiling of lncRNAs was identified in C3H10T1/2 mouse MSCs undergoing early osteogenic differentiation, and several lncRNAs exhibited co-expression with their neighboring mRNA related to osteogenesis, such as mouse lincRNA0231 and its neighboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), as well as lncRNA NR_027652 and nearby DLK1.8 Another study indicated that the decreased lncRNA-ANCR (anti-differentiation noncoding RNA) promotes osteogenic differentiation by regulating EZH2/Runx2.9 Also, lncRNA-MEG3 induced osteogenesis by dissociating BMP4 repressor SOX2 from BMP4 promoter and inducing BMP4 expression.10 lncRNA AK141205 could induce osteoblast differentiation by positively promoting CXCL13 expression.11 Furthermore, lncRNA H19 was discovered to induce osteogenic differentiation by decoying miR-141 and miR-22, and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling.12 However, the whole spectrum of lncRNA-modulating osteogenesis remains not fully uncovered.

Linc-ROR, one recently identified 2.6-kb lncRNA located in chromosome 18, consists of four exons.13 Linc-ROR is highly expressed in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs),14 and maintains the reprogramming capacity as well as the self-renewal ability.15 Serving as a ceRNA or natural sponge, linc-ROR regulates the expression of transcriptional factors Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog in human ESCs through targeting miR-145.14 Recent studies also documented that linc-ROR mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal (EMT) transition, migration, chemosensitivity, and cancer stem cell formation.16, 17, 18, 19 In the present study, we defined a novel role of linc-ROR in osteogenic differentiation of human bone-marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs). It was found that linc-ROR promoted osteogenic differentiation in vitro through serving as a miRNA sponge for miR-145 and miR-138, leading to ZEB2 de-repression, which eventually activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Results

Linc-ROR Promoted Osteogenic Differentiation of Human BM-MSCs

To identify the potential role of linc-ROR in osteogenesis, we examined its expression pattern during osteogenic differentiation. As shown in Figures 1A and S1, linc-ROR was found to be upregulated during osteogenic differentiation. For further investigation of the effect of linc-ROR on osteoblast, we used lentiviral vectors to stably restore or silence the expression of linc-ROR in human BM-MSCs, and the established stable cells were verified by qRT-PCR examination (Figure S2). Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, an early marker of osteogenesis, was measured at day 3 with osteo-induction, and it was increased in linc-ROR-overexpressing cells but decreased in linc-ROR-knockdown cells (Figure 1B). The calcium nodules were evaluated by alizarin red S staining assays at day 14, and the results indicated a significantly enhanced calcium nodules formation in linc-ROR-overexpressing cells, whereas it was reduced in linc-ROR knockdown cells (Figure 1C). Expression levels of several osteogenic marker genes were measured at day 7, and ALP, OCN, and Osx were upregulated by linc-ROR overexpression, whereas they were downregulated by linc-ROR knockdown in human BM-MSCs (Figure 1D). All of these data showed that linc-ROR promoted osteogenesis of human MSCs.

Figure 1.

Linc-ROR Promoted Osteogenesis of Human BM-MSCs

(A) The osteoblast differentiation of human BM-MSCs was initiated by osteogenic inducer and harvested at indicated time points. At days 0, 3, 6, and 9, the expression level of linc-ROR was monitored by qRT-PCR assays. (B and C) The human BM-MSCs were transfected with sh-Linc-ROR or pLinc-ROR overexpression vectors, and osteogenesis was initiated. At day 3, the alkaline phosphatase activity was visualized by NBT/BCIP precipitation (B). At day 14, the calcified nodules of human BM-MSCs were visualized by alizarin red S staining (C). (D) The mRNA expression level of osteogenesis-related marker genes after linc-ROR overexpression or sh-linc-ROR transfection was examined by qRT-PCR assays. n = 3. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

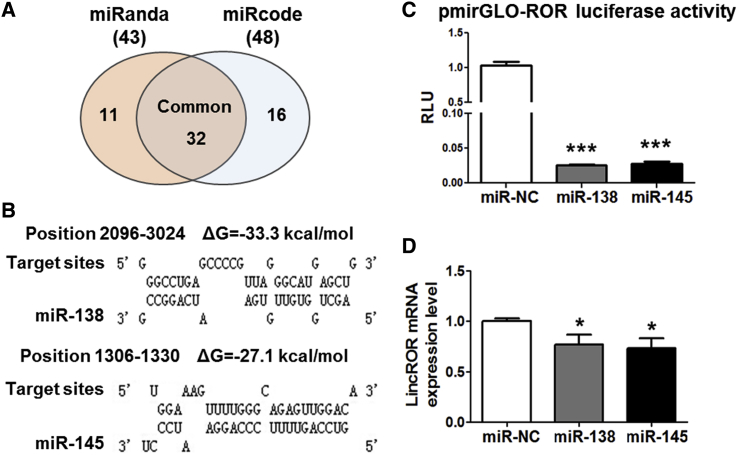

Linc-ROR Served as a miRNA Sponge for miR-138 and miR-145

Previous studies demonstrated that linc-ROR functioned as a natural sponge for miR-145 to mediate carcinogenesis.20 Therefore, we suppose that some miRNAs might directly bind this lncRNA to mediate osteogenic differentiation. To find the miRNAs that target linc-ROR, two in silico bioinformatic programs were used to predict the candidates. We identified 43 target genes by miRanda (http://www.microrna.org) and 48 targets by miRCode (http://www.mircode.org), 32 of which were common by both programs (Figure 2A). To further identify the predicted candidates, another bioinformatics program TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org) was applied. Among them, two miRNAs, miR-138 and miR-145, were considered as the most promising candidates based on their lowest binding free energy (Figure 2B). To validate this prediction, we next generated a luciferase reporter harboring linc-ROR full-length sequence and applied for luciferase reporter assay. It was shown that miR-138 and miR-145 significantly repressed the luciferase activity of the generated luciferase reporter (Figure 2C). Furthermore, miR-138 and miR-145 could also suppress the linc-ROR expression (Figure 2D). Collectively, all these results revealed that miR-138 and miR-145 directly targeted linc-ROR sequence and led to its mRNA degradation.

Figure 2.

Linc-ROR Directly Targeted miR-138 and miR-145

(A) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between 43 miRNA targets of linc-ROR interaction predicted by miRanda (dark gray) and 48 miRNA targets predicted by miRcode. Thirty-two common targets were further applied to TargetScan analysis. (B) Schematic diagrams of the mutual interplays between miRNA and linc-ROR. miRNA binding position and calculated ΔG values are shown on the top (kcal/mol). (C) miR-138 or miR-145 mimics were co-transfected with pmirGLO-ROR luciferase reporter into HEK293 cells, and the luciferase activities were measured. (D) Linc-ROR expression level was examined by qRT-PCR assays in human BM-MSCs transfected with miR-138 or miR-145 mimics. n = 3. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

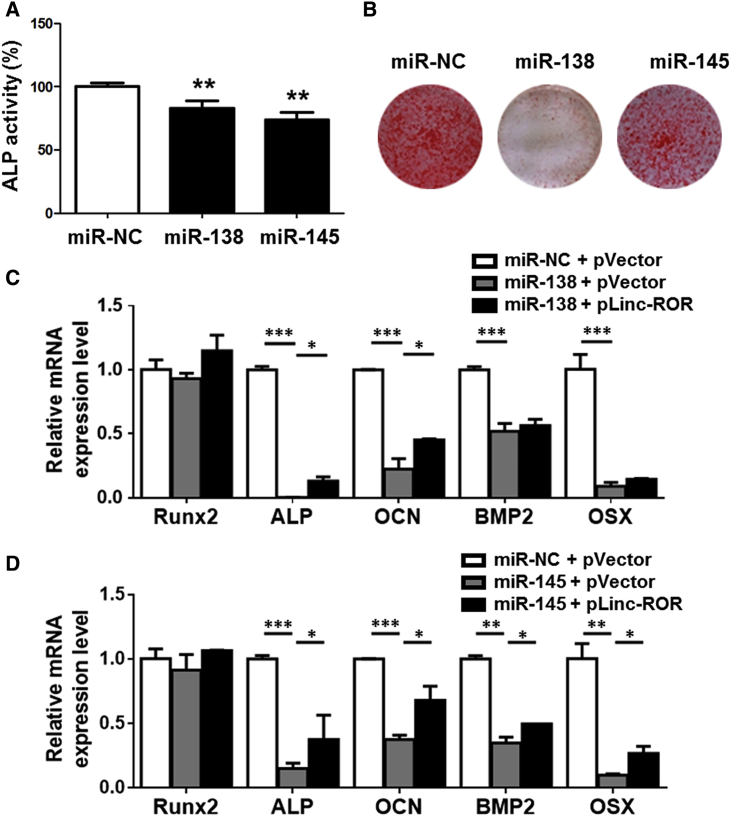

miR-138 and miR-145 Were Negative Regulators of Osteoblast Differentiation

To further elucidate the biological function of miR-138 and miR-145 in MSCs, we examined the effects of miR-138 and miR-145 on osteogenesis by transfecting miRNA mimics into human BM-MSCs. As shown in Figure 3A, the two miRNAs could suppress the ALP activity at day 3 when compared with the negative control (NC) group. Further alizarin red S staining confirmed that the two miRNAs significantly repressed calcium nodule formation after 14-day osteoblast differentiation (Figure 3B). Thereafter, a variety of osteogenesis-related marker genes such as ALP, OCN, BMP2, and Osx were suppressed by miR-138 and miR-145, whereas linc-ROR overexpression slightly recovered the repression induced by the two miRNAs (Figures 3C and 3D). All of these data suggest that the two miRNAs act as negative regulators of osteoblast differentiation.

Figure 3.

miR-138 and miR-145 Suppressed Osteoblast Differentiation

(A and B) The human BM-MSCs were transfected with miR-138 or miR-145 mimics, and ALP activity was visualized by NBT/BCIP precipitation at day 3 (A). The calcified nodules were visualized by alizarin red S staining at day 14 (B). (C and D) The expression of osteogenesis marker genes was suppressed by miR-138, whereas pLinc-ROR partially rescued the suppressive effect in MSCs (C). miR-145 also suppressed the osteogenic marker genes expression, whereas pLinc-ROR partially reverse the suppressive effects (D). n = 3. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

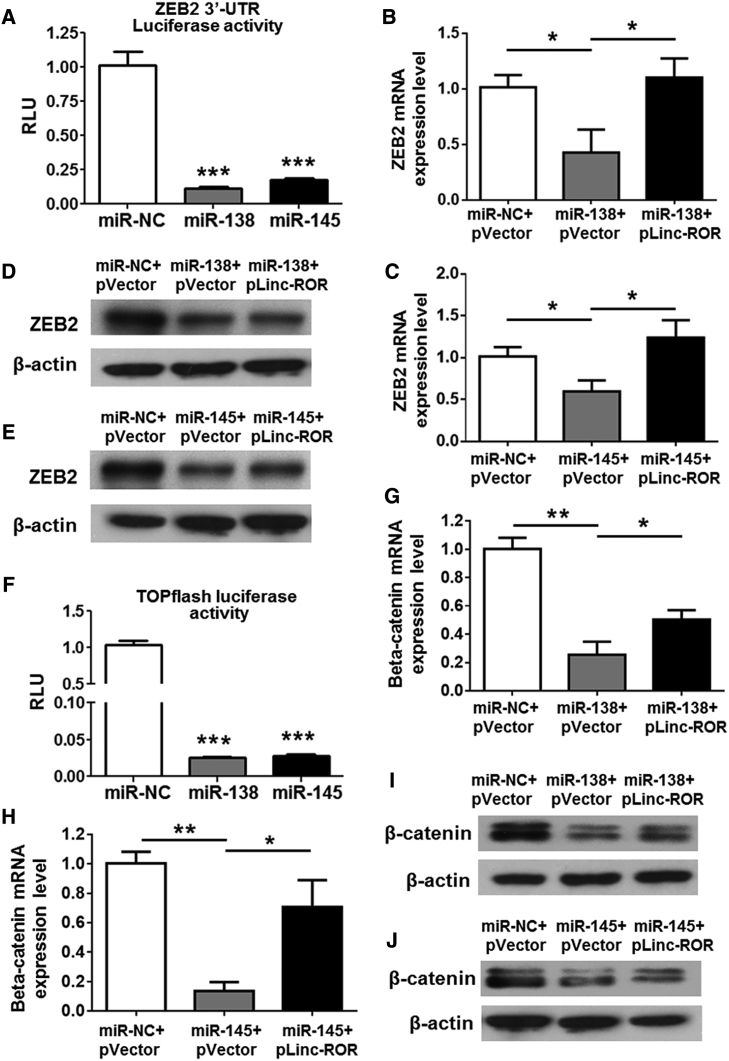

miR-138 and miR-145 Suppressed the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling by Targeting ZEB2

miRNAs function as regulators in multiple biological activities through suppressing the target genes expression. In terms of the suppressive effect of miR-138 and miR-145 on osteogenesis, we tried to identify the candidate protein-coding genes targeted by the two miRNAs. Among the candidates predicted by the bioinformatics analysis, ZEB2 was found to be of great interest. To confirm whether the two miRNAs could bind to the 3′ UTR region of ZEB2, we inserted the binding sites into the pmiR-GLO vector to generate a luciferase reporter. The two miRNAs together with the generated luciferase reporter were co-transfected into HEK293 cells, and it was shown that miR-138 and miR-145 dramatically suppressed the luciferase activity of the generated luciferase reporter (Figure 4A). By transfecting BM-MSCs with miRNA mimics, the results showed that miR-138 and miR-145 significantly induced the downregulation of ZEB2 at both mRNA and protein levels, whereas linc-ROR reversed their suppressive effects (Figures 4B–4E).

Figure 4.

miR-138 and miR-145 Suppressed the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling by Targeting ZEB2

(A) miR-138 or miR-145 mimics were co-transfected with the luciferase reporter harboring 3′ UTR of ZEB2 mRNA into HEK293 cells, and the luciferase activities were measured. (B–E) ZEB2 expression was suppressed by miR-138, whereas it was slightly rescued by the pLinc-ROR vector at mRNA (B) and protein (D) levels. Expression of ZEB2 was also repressed by miR-145, and the suppressive expression was partially reversed by miR-145 pLinc-ROR at mRNA (C) and protein (E) levels. (F) miR-138 or miR-145 were co-transfected with TOPFlash luciferase reporter into HEK293 cells, and the luciferase activities were measured. (G–J) Beta-catenin mRNA (G) and protein (I) expression levels were suppressed by miR-138, and the suppressive effect was partially reversed by pLinc-ROR. Moreover, Beta-catenin mRNA (H) and protein (J) expression levels were also reduced by miR-145, and the suppressive expression was rescued in part by pLinc-ROR. n = 3. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

As well known, Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been reported to play a crucial role in osteoblasts, and ZEB2 regulated the expression of β-catenin.21 miR-145 could inhibit hepatic stellate cell activation and proliferation through regulating ZEB2 and Wnt/β-catenin pathway.22 Therefore, we sought to determine the regulation of the two miRNAs on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The luciferase activity of Wnt signaling reporter TOPFlash, which contains binding sites for β-catenin, was examined and the impaired luciferase activity was observed in miR-138 and miR-145 transfection groups (Figure 4F). Moreover, we also found that the expression of β-catenin was suppressed by the two miRNAs at mRNA and protein levels, whereas linc-ROR overexpression rescued these suppressive effects (Figures 4G–4J). All of these data indicated that miR-138 and miR-145 induced the inactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling via directly targeting ZEB2.

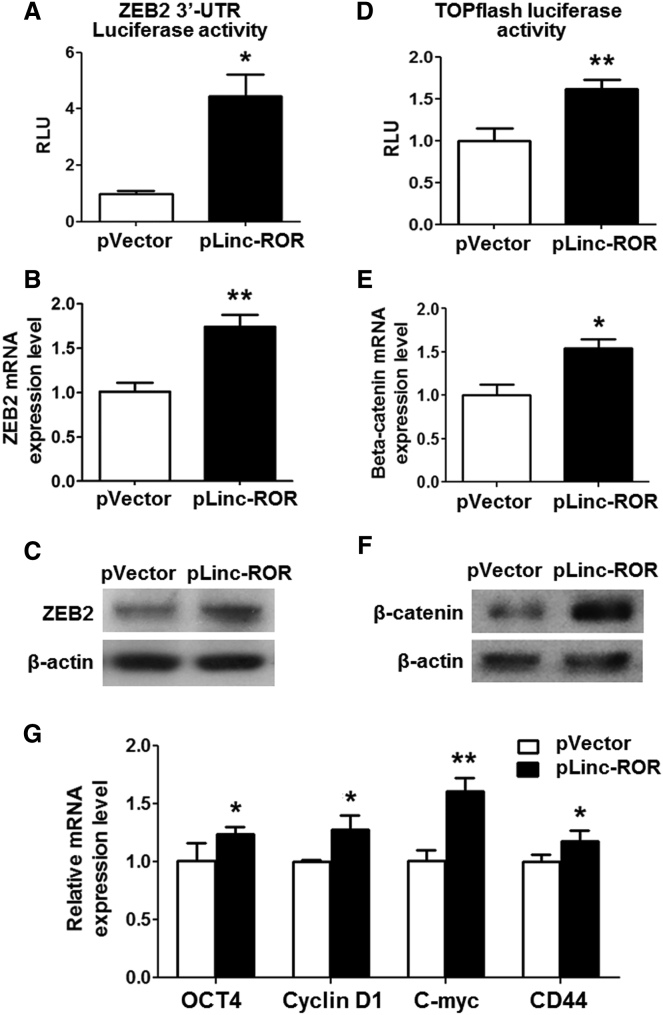

Linc-ROR Activated the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling by Promoting ZEB2 Expression

Considering that linc-ROR acted as a ceRNA for miR-138 and miR-145, which could inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin signaling through suppressing ZEB2 expression, these findings promoted us to investigate whether linc-ROR could regulate β-catenin expression in this manner. The linc-ROR overexpression vector was co-transfected with the ZEB 3′ UTR luciferase reporters harboring miRNA binding sites, and the results showed that linc-ROR significantly promoted the luciferase activity (Figure 5A). Moreover, the expression of ZEB2 was upregulated by linc-ROR at both mRNA and protein levels (Figures 5B and 5C). We also found that linc-ROR activated the luciferase activity of TOPFlash, which implies that linc-ROR could activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Figure 5D). Moreover, the expression of β-catenin was promoted by linc-ROR at mRNA and protein levels (Figures 5E and 5F). Furthermore, several downstream target genes such as c-Myc, CD44, Oct4, as well as cyclin D1 were upregulated by ectopic expression of linc-ROR (Figure 5G), indicating that linc-ROR plays a significant role in mediating the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Figure 5.

Linc-ROR Activated the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

(A) pLinc-ROR vector was co-transfected with ZEB2 3′ UTR luciferase reporter into HEK293 cells, and the luciferase activities were measured. (B and C) ZEB2 mRNA (B) and protein (C) expression levels were evaluated with linc-ROR overexpression. (D) pLinc-ROR vector was co-transfected with TOPFlash luciferase reporter into HEK293 cells, and the luciferase activities were measured. (E and F) Beta-catenin mRNA (E) and protein (F) expression levels were also upregulated by pLinc-ROR vector. (G) Several downstream target genes of Wnt/β-catenin signaling were examined in linc-ROR-overexpressing BM-MSCs by qRT-PCR assays. n = 3. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Discussion

As a regulator of reprogramming, linc-ROR was first reported to mediate the self-renewal ability of stem cells and regulate the downstream stem-related genes Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog by decoying miR-145.14 Increasing evidence revealed linc-ROR played an oncogenic role in multiple cancers.18 It could activate EMT and contribute to tumorigenesis and metastasis in endometrial cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer, and breast cancer.16, 23, 24, 25 On the other hand, linc-ROR could enhance chemoresistance in pancreatic and breast cancers,13, 26 and promote radioresistance in colorectal carcinoma (CRC) cells as well.27 In addition, linc-ROR also promoted the stem cell-like features of pancreatic cancer cells and tumorigenicity potential in vitro and in vivo.28 More importantly, linc-ROR has been served as a biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis of breast cancer and oral cancer.29, 30 Collectively, the functions of linc-ROR in carcinogenesis have been studied well. However, the function and precise mechanism by which linc-ROR mediated the osteogenic differentiation were not fully understood.

In the present study, we reported that linc-ROR promoted osteogenic differentiation of human BM-MSCs. It seems controversial with the initially reported self-renewal maintenance ability. We suppose this phenomenon may be caused by spatial and temporal regulation of gene expression during the tissue and organ development. Several lncRNAs have also been reported to play mutual function as linc-ROR did, i.e., lncRNA MALAT1 and H19. Malat1 could maintain the undifferentiated status of early-stage hematopoietic cells,31 and it was also demonstrated to regulate myogenesis differentiation through increasing MyoD transcriptional activity.32 As for H19, many studies showed that it mediated osteogenesis, myogenesis, tenogenesis, and chondrogenesis of MSCs.12, 33, 34 However, H19 was also found to keep the stem characteristics and maintain the self-renewal ability of ESCs.35 These studies provide strong evidence for the mutual regulation mode in which lncRNAs play different roles during various developmental stages.

Serving as natural miRNA sponge or RNA decoy, lncRNAs may modulate their target miRNAs, and thus regulate their downstream gene expression. In this study, linc-ROR was found to interact with miR-138 and miR-145 as a miRNA sponge and participated in miRNA-involved osteogenesis. Previous studies have demonstrated that miRNAs orchestrate bone homeostasis and skeletal development.36 What is more, it is widely accepted that miRNAs have emerged as a fundamental modulator of osteogenesis-related signaling pathways. As previously reported, miR-138 suppressed osteoblast differentiation of human MSCs, as well as in vivo bone formation by inhibiting the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling pathway.37 miR-145 was also found to negatively regulate osteoblast differentiation by targeting osterix, a key regulator of osteoblast differentiation.38 In our study, linc-ROR competitively targeted miR-138 and miR-145, and interfered with them binding to 3′ UTR of ZEB2, and hence elevated ZEB2 expression.

ZEB2 is a member of the Zfh1 family of two-handed zinc-finger/homeodomain proteins that acts as a key regulator in the EMT process in tumorigenesis and activates cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. ZEB2 could also activate the expression of β-catenin.21 Therefore, linc-ROR may promote ZEB2 expression and hence induce β-catenin upregulation by decoying miR-138 and miR-145. On the other hand, ZEB2 could increase the cytosolic β-catenin expression by regulating E-cadherin/Wnt signaling. In general, cytosolic β-catenin is tightly orchestrated by Wnt signaling for its stabilization and cadherin pathway for β-catenin plasma sequestering,39 whereas E-cadherin is the central component for structural integrity and functional maintenance of cadherin-catenin complex. Decreased E-cadherin may release more cell-surface-sequestrated β-catenin into cytosol and stimulate β-catenin nuclear translocation and transcription activity. As an E-cadherin regulator, ZEB2 could bind to the promoter region of E-cadherin and decrease its mRNA expression. Reduced expression of ZEB2 could induce more membrane-associated β-catenin dissociation into cytoplasm and more β-catenin nuclear translocation and activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Our results also demonstrated that linc-ROR could enhance ZEB2 expression and consequently activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Specifically, miR-145 was also reported to de-activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and suppress the activation and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells through suppressing ZEB2 expression,22 which further strengthens our finding that linc-ROR could activate ZEB2 expression and induce Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway-regulated osteogenesis.

Linc-ROR was demonstrated to be involved in bone regeneration through regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Based on previous in vitro and in vivo studies, this signaling was critical for bone and tooth formation and development. Additionally, β-catenin also plays significant roles in mechanosensation and transduction.38, 40 Besides for sensing mechanical loading, it is also essential for cell viability, protection against apoptotic factors, communication, and bone formation in osteocytes. Therefore, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway may be considered as a promising target for developing therapeutic strategies. Several lncRNAs have been demonstrated to regulate bone homeostasis through regulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. lncRNA H19 was found to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and stimulate osteoblast differentiation of human BM-MSCs by decoying miR-141 and miR-22.12 Another ANCR was reported to regulate periodontal ligament stem cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation via the canonical Wnt signaling.41 Furthermore, lncRNA ZBED3-AS1 could activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling and stimulate chondrogenesis in human synovial-fluid-derived MSCs.42 What is more, certain lncRNAs could be regulated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling during osteogenesis differentiation. A putative osteo-suppressing lncRNA HOTAIR was downregulated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which led to the upregulation of downstream osteogenic markers ALP and BMP2.43 These findings indicated that lncRNA and Wnt could be cross-talking with each other during osteogenic regulation. In the current study, ZEB2, a suppressor of E-cadherin, was promoted and Wnt/β-catenin signaling was activated by linc-ROR, which disclosed a complicated interplay between linc-ROR, E-cadherin, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Based on previous reports and our results, a schematic mechanism of linc-ROR in osteogenesis (Figure S3) was suggested: linc-ROR could induce Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and promote osteogenic differentiation through linc-ROR/miRNA/ZEB2/E-cadherin regulation axis. Another alternative mechanism for linc-ROR regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway may be the linc-ROR/E-cadherin/Lrp5/β-catenin pathway. A previous study demonstrated that suppressive E-cadherin expression may stimulate Lrp5 and Lrp6 release from cell surface into cell cytosol and result in the stabilized cytoplastic β-catenin level, as well as the enhanced osteogenic differentiation.44 However, this hypothesis requires more experimental evidence to confirm.

Taken together, we have characterized the novel role of linc-ROR in regulating osteogenic differentiation of human BM-MSCs. Linc-ROR functions as an important regulator of osteogenesis via acting as a miRNA sponge for miR-138 and miR-145, and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Further studies are required to confirm its clinical significance with developing linc-ROR as a potential therapeutic target for bone diseases.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Osteo-Induction

The HEK293 cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/neomycin (PSN). The human BM-MSCs were isolated from bone marrow, which aspirated from healthy donors, and then cultured and characterized using flow cytometry for MSC phenotypic markers like CD3-PE, CD16-FITC, CD19-FITC, CD33-FITC, CD34-PE, CD38-FITC, CD45-FITC, and CD133-PE. Isolated human BM-MSCs were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium Alpha (MEMα) plus 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% PSN. To initiate osteogenic differentiation of human MSCs, they were seeded into a 12-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well; then the osteo-differentiation was induced by addition of 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and 10 mM glycerol 2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) into the culture medium. The differentiation medium was changed every 3 days.

Plasmid Generation and Cell Transfection

Total length of linc-ROR was amplified by PCR from human MSCs cDNA and subcloned into pBabe vector for transient or stable expression of linc-ROR in human BM-MSCs. Human ZEB2 3′ UTR sequence as well as total length of linc-ROR obtained before were subcloned into the pmiR-GLO vector. All of the cDNA sequences were obtained by database searching (lncRNAdb: http://www.lncrnadb.org; NCBI: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The primer for vector construction was included in Table S1. The linc-ROR knockdown plasmid was kindly provided by Prof. Houqi Liu, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China. TOPFlash plasmid was purchased from Upstate Cell Signaling (Billerica, MA, USA). All of the miRNA mimics and antisense inhibitors were purchased from GenePharma Company (Shanghai, China). miRNA mimics and inhibitors as well as DNA plasmids were transfected using transfection reagent Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Establishment of Stable Cell Lines

Linc-ROR stable expressing human BM-MSC cells were generated using retrovirus-mediated gene delivery method as previously described. To produce retrovirus for infection, pBabe-linc-ROR vector or corresponding control pBabe vector were co-transfected with an equal amount of viral packaging vector pCL-Ampho into HEK293 cells by using the polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection reagent (Invitrogen, USA),45 Lentivirus gene delivery system was employed for sh-linc-ROR vector transfection. In brief, pLUNIG-sh-linc-ROR vector or pLUNIG-sh-NC negative control vector was co-transfected with three packaging vectors (pMDLg/pRRE, pRSV-REV, and pCMV-VSVG) as described previously.46 After transfection, the supernatant media containing retrovirus particles were collected and subsequently filtered by 0.45-μm pore-size nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, USA). The human BM-MSCs were infected with the retroviral particles by the addition of hexadimethrine bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Retrovirus or lentivirus-infected human BM-MSCs were selected by puromycin at the concentration of 0.2 μg/mL or G418 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 500 μg/ml, respectively. After antibiotics selection for around 7 days, remaining cultured cells were collected, and overexpression or knockdown of linc-ROR was confirmed by qRT-PCR examination.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA of cultured cells was harvested with RNAiso Plus reagent (TaKaRa, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After RNA extraction, cDNAs were reverse transcribed from RNA samples by PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa, Japan). The Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, USA) was applied for the qRT-PCR of target mRNA detection using ABI 7300 Fast Real-Time PCR Systems (Applied Biosystem, USA). The relative fold changes of candidate genes were analyzed by using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primers for real-time PCR were included in Table S1.

Western Blot Analysis

Total protein of harvested cells was lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40]) supplemented with complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, USA), and the soluble protein was collected by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Soluble protein fractures were then mixed with 5× sample loading buffer (Roche, USA) and boiled for 5 min. To perform western blot analysis, we subjected the protein samples to SDS-PAGE gel and electrophoresed at 120 V for 2 hr. After that, the protein from SDS-PAGE gel was electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane at 100 V for 1 hr at 4°C. The membranes were then blocked with 5% non-fat milk and probed with the following antibodies: β-catenin (1:3,000; Cell Signaling Technology, USA), ZEB2 (1: 1,000, Sigma, USA), and β-actin (1:4,000; Sigma, USA). The results were visualized on the X-Ray film by Kodak film developer (Fujifilm, Japan).

Luciferase Assay

Dual-luciferase assay was performed to evaluate the luciferase activity of the reporter constructs according to the instructions of dual-luciferase assay reagents (Promega, USA) with some modifications. In brief, HEK293 cells were seeded on a 24-well plate, and the cells were allowed to grow until 80% confluency. Cells were then transfected with TOPFlash or pmiR-GLO luciferase reporter plasmids together with linc-ROR expression vectors or miRNA mimics. The pRSV-β-galactoside (ONPG) vector was co-transfected into HEK293 cells as an internal control for normalization. The plate was placed into a PerkinElmer VictorTM X2 2030 multilabel reader (Waltham, USA) to measure the firefly luciferase activity, as well as the β-galactosidase activity. The ratio of firefly luciferase to β-galactosidase activity in each sample was revealed as a measurement of the normalized luciferase activity. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

ALP Activity and Alizarin Red Staining

Human BM-MSCs were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well, and osteoblast differentiation was induced when cells reach 100% confluence. The alizarin red S staining was performed at day 14 with osteo-induction. In brief, the human BM-MSCs were washed with PBS and fixed with 70% ethanol for 30 min. Human BM-MSCs were then stained with 2% alizarin red S staining solution for 10 min. The stained calcified nodules were scanned using Epson launches Perfection V850 (Seiko Epson, Japan). The ALP activity assay was performed at day 3, the cells were harvested by cell scratch, and ALP activity was measured and analyzed by ALP staining following the published protocol46 or using ALP diagnosis kit (Sigma, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The ALP activity was normalized to total cell proteins.

Statistical Analysis

Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. Two groups of data were statistically analyzed using two-tailed Student’s t test. The results were considered to be statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

G.L. and J.-f.Z. spearheaded and supervised all of the experiments. G.L., J.-f.Z., W.-m.F., and L.F. designed this project. L.F., L.S., Y.-f.L., and B.W. conducted experiments. L.F., L.S., and B.W. analyzed data. T.T. and W.H. provided materials. L.F., G.L., W.-m.F., and J.-f.Z. prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81772404, 81773066, 81371946, 81430049, and 81772322) and the Hong Kong Government Research Grant Council, General Research Fund (14119115, 14160917, 9054014 N_CityU102/15, and T13-402/17-N). This study was also supported in part by the SMART program, the Lui Che Woo Institute of Innovative Medicine, and The Chinese University of Hong Kong, and research was made possible by resources donated by Lui Che Woo Foundation Limited. We thank Prof. Houqi Liu for kindly providing the sh-linc-ROR plasmid.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures and one table and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2018.03.004.

Contributor Information

Gang Li, Email: gangli@cuhk.edu.hk.

Jin-fang Zhang, Email: zhangjf06@gzucm.edu.cn.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Chen C.H., Wang S.S., Wei E.I., Chu T.Y., Hsieh P.C. Hyaluronan enhances bone marrow cell therapy for myocardial repair after infarction. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:670–679. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An J., Yang H., Zhang Q., Liu C., Zhao J., Zhang L., Chen B. Natural products for treatment of osteoporosis: the effects and mechanisms on promoting osteoblast-mediated bone formation. Life Sci. 2016;147:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marini J.C., Reich A., Smith S.M. Osteogenesis imperfecta due to mutations in non-collagenous genes: lessons in the biology of bone formation. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2014;26:500–507. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng X., McDonald J.M. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glenn J.D., Whartenby K.A. Mesenchymal stem cells: emerging mechanisms of immunomodulation and therapy. World J. Stem Cells. 2014;6:526–539. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i5.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagano T., Fraser P. No-nonsense functions for long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2011;145:178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beermann J., Piccoli M.T., Viereck J., Thum T. Non-coding RNAs in development and disease: background, mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches. Physiol. Rev. 2016;96:1297–1325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuo C., Wang Z., Lu H., Dai Z., Liu X., Cui L. Expression profiling of lncRNAs in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal stem cells undergoing early osteoblast differentiation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013;8:463–467. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu L., Xu P.C. Downregulated LncRNA-ANCR promotes osteoblast differentiation by targeting EZH2 and regulating Runx2 expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;432:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuang W., Ge X., Yang S., Huang M., Zhuang W., Chen P., Zhang X., Fu J., Qu J., Li B. Upregulation of lncRNA MEG3 promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from multiple myeloma patients by targeting BMP4 transcription. Stem Cells. 2015;33:1985–1997. doi: 10.1002/stem.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H., Zhang Z., Chen Z., Zhang D. Osteogenic growth peptide promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells mediated by LncRNA AK141205-induced upregulation of CXCL13. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;466:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang W.C., Fu W.M., Wang Y.B., Sun Y.X., Xu L.L., Wong C.W., Chan K.M., Li G., Waye M.M., Zhang J.F. H19 activates Wnt signaling and promotes osteoblast differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20121. doi: 10.1038/srep20121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y.M., Liu Y., Wei H.Y., Lv K.Z., Fu P.F. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-ROR reverses gemcitabine-induced autophagy and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:59604–59617. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y., Xu Z., Jiang J., Xu C., Kang J., Xiao L., Wu M., Xiong J., Guo X., Liu H. Endogenous miRNA sponge lincRNA-RoR regulates Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 in human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Dev. Cell. 2013;25:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi K., Yan I.K., Kogure T., Haga H., Patel T. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of long non-coding RNA ROR modulates chemosensitivity in human hepatocellular cancer. FEBS Open Bio. 2014;4:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou P., Zhao Y., Li Z., Yao R., Ma M., Gao Y., Zhao L., Zhang Y., Huang B., Lu J. LincRNA-ROR induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and contributes to breast cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1287. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhamija S., Diederichs S. From junk to master regulators of invasion: lncRNA functions in migration, EMT and metastasis. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;139:269–280. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan Y., Li C., Chen J., Zhang K., Chu X., Wang R., Chen L. The emerging roles of long noncoding RNA ROR (lincRNA-ROR) and its possible mechanisms in human cancers. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016;40:219–229. doi: 10.1159/000452539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou X., Gao Q., Wang J., Zhang X., Liu K., Duan Z. Linc-RNA-RoR acts as a “sponge” against mediation of the differentiation of endometrial cancer stem cells by microRNA-145. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;133:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao S., Wang P., Hua Y., Xi H., Meng Z., Liu T., Chen Z., Liu L. ROR functions as a ceRNA to regulate Nanog expression by sponging miR-145 and predicts poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:1608–1618. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi S., Song Y., Peng Y., Wang H., Long H., Yu X., Li Z., Fang L., Wu A., Luo W. ZEB2 mediates multiple pathways regulating cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis in glioma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou D.D., Wang X., Wang Y., Xiang X.J., Liang Z.C., Zhou Y., Xu A., Bi C.H., Zhang L. MicroRNA-145 inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and proliferation by targeting ZEB2 through Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2016;75:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan Y., Chen J., Tao L., Zhang K., Wang R., Chu X., Chen L. Long noncoding RNA ROR regulates chemoresistance in docetaxel-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cells via epithelial mesenchymal transition pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:33144–33158. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhan H.X., Wang Y., Li C., Xu J.W., Zhou B., Zhu J.K., Han H.F., Wang L., Wang Y.S., Hu S.Y. LincRNA-ROR promotes invasion, metastasis and tumor growth in pancreatic cancer through activating ZEB1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 2016;374:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J., Zhang A., Ho T.T., Zhang Z., Zhou N., Ding X., Zhang X., Xu M., Mo Y.Y. Linc-RoR promotes c-Myc expression through hnRNP I and AUF1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:3059–3069. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C., Zhao Z., Zhou Z., Liu R. Linc-ROR confers gemcitabine resistance to pancreatic cancer cells via inducing autophagy and modulating the miR-124/PTBP1/PKM2 axis. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2016;78:1199–1207. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-3178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang P., Yang Y., An W., Xu J., Zhang G., Jie J., Zhang Q. The long noncoding RNA-ROR promotes the resistance of radiotherapy for human colorectal cancer cells by targeting the p53/miR-145 pathway. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017;32:837–845. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu Z., Li G., Li Z., Wang Y., Zhao Y., Zheng S., Ye H., Luo Y., Zhao X., Wei L. Endogenous miRNA Sponge LincRNA-ROR promotes proliferation, invasion and stem cell-like phenotype of pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Death Discov. 2017;3:17004. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arunkumar G., Deva Magendhra Rao A.K., Manikandan M., Arun K., Vinothkumar V., Revathidevi S., Rajkumar K.S., Rajaraman R., Munirajan A.K. Expression profiling of long non-coding RNA identifies linc-RoR as a prognostic biomarker in oral cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017;39 doi: 10.1177/1010428317698366. 1010428317698366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao T., Wu L., Li X., Dai H., Zhang Z. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-ROR as a potential biomarker for the diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of breast cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2017;20:165–173. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma X.Y., Wang J.H., Wang J.L., Ma C.X., Wang X.C., Liu F.S. Malat1 as an evolutionarily conserved lncRNA, plays a positive role in regulating proliferation and maintaining undifferentiated status of early-stage hematopoietic cells. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:676. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1881-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X., He L., Zhao Y., Li Y., Zhang S., Sun K., So K., Chen F., Zhou L., Lu L. Malat1 regulates myogenic differentiation and muscle regeneration through modulating MyoD transcriptional activity. Cell Discov. 2017;3:17002. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2017.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y.F., Liu Y., Fu W.M., Xu J., Wang B., Sun Y.X., Wu T.Y., Xu L.L., Chan K.M., Zhang J.F., Li G. Long noncoding RNA H19 accelerates tenogenic differentiation and promotes tendon healing through targeting miR-29b-3p and activating TGF-β1 signaling. FASEB J. 2017;31:954–964. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600722R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y., Li G., Zhang J.F. The role of long non-coding RNA H19 in musculoskeletal system: a new player in an old game. Exp. Cell Res. 2017;360:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin Y., Wang H., Liu K., Wang F., Ye X., Liu M., Xiang R., Liu N., Liu L. Knockdown of H19 enhances differentiation capacity to epidermis of parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells. Curr. Mol. Med. 2014;14:737–748. doi: 10.2174/1566524014666140724101035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lian J.B., Stein G.S., van Wijnen A.J., Stein J.L., Hassan M.Q., Gaur T., Zhang Y. MicroRNA control of bone formation and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012;8:212–227. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan P., Bonewald L.F. The role of the wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in formation and maintenance of bone and teeth. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016;77(Pt A):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamel M.A., Picconi J.L., Lara-Castillo N., Johnson M.L. Activation of β-catenin signaling in MLO-Y4 osteocytic cells versus 2T3 osteoblastic cells by fluid flow shear stress and PGE2: Implications for the study of mechanosensation in bone. Bone. 2010;47:872–881. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nelson W.J., Nusse R. Convergence of Wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science. 2004;303:1483–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.1094291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gortazar A.R., Martin-Millan M., Bravo B., Plotkin L.I., Bellido T. Crosstalk between caveolin-1/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and β-catenin survival pathways in osteocyte mechanotransduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:8168–8175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.437921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia Q., Jiang W., Ni L. Down-regulated non-coding RNA (lncRNA-ANCR) promotes osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 2015;60:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ou F., Su K., Sun J., Liao W., Yao Y., Zheng Y., Zhang Z. The LncRNA ZBED3-AS1 induces chondrogenesis of human synovial fluid mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;487:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.04.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carrion K., Dyo J., Patel V., Sasik R., Mohamed S.A., Hardiman G., Nigam V. The long non-coding HOTAIR is modulated by cyclic stretch and WNT/β-CATENIN in human aortic valve cells and is a novel repressor of calcification genes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vinyoles M., Del Valle-Pérez B., Curto J., Viñas-Castells R., Alba-Castellón L., García de Herreros A., Duñach M. Multivesicular GSK3 sequestration upon Wnt signaling is controlled by p120-catenin/cadherin interaction with LRP5/6. Mol. Cell. 2014;53:444–457. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang W.C., Wang Y., Xiao L.J., Wang Y.B., Fu W.M., Wang W.M., Jiang H.Q., Qi W., Wan D.C., Zhang J.F., Waye M.M. Identification of miRNAs that specifically target tumor suppressive KLF6-FL rather than oncogenic KLF6-SV1 isoform. RNA Biol. 2014;11:845–854. doi: 10.4161/rna.29356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J.F., Fu W.M., He M.L., Xie W.D., Lv Q., Wan G., Li G., Wang H., Lu G., Hu X. MiRNA-20a promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by co-regulating BMP signaling. RNA Biol. 2011;8:829–838. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.5.16043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.