Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) is a class of endogenous noncoding RNAs that, unlike linear RNAs, form covalently closed continuous loops and have recently shown huge capabilities as gene regulators in mammals. However, little is known about their roles in cancer initiation and progression, such as glioma. In this study, we determined the expression level of circRNA ITCH (cir-ITCH) in glioma specimens and further investigated its functional role in glioma cells. By performing Taq-man based RT-qPCR, we identified that cir-ITCH was downregulated in glioma tissues and cell lines. Receiver operating curve analysis suggested cir-ITCH showed a relatively high diagnostic accuracy. Kaplan-Meier assay revealed that decreased cir-ITCH level was associated with poor survival of glioma patients. The functional relevance of cir-ITCH was further examined by biological assays. Cir-ITCH significantly promoted the capacities of cell proliferation, migration and invasion of glioma cells. The linear isomer of cir-ITCH, ITCH gene was then identified as the down stream target. Subsequently, RNA immunoprecipitation clearly showed that cir-ITCH sponged miR-214, which further promoted the ITCH expression. Finally, the gain and loss functional assays indicate that cir-ITCH plays an anti-oncogenic role through sponging miR-214 and regulating ITCH-Wnt/β-catenin pathway. These results suggest that cir-ITCH is a tumor-suppressor gene in glioma and may serve as a promising prognostic biomarker for glioma patients. Therefore, restoration of cir-ITCH expression could be a future direction to develop a novel treatment strategy.

Keywords: Cir-ITCH, glioma, miR-214, linear ITCH, Wnt/β-catenin pathway

Introduction

Glioma is one of the most common types of primary brain tumors in adults, and represents one of the most aggressive and lethal human cancer types [1]. Most of the patients are at advanced stages at the time of diagnosis, and the prognosis of these patients still remains poor [2]. The standard treatment regimen includes surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy [3]. Despite advances in this therapeutic regimen, treatment usually fails due to a combination of chemo- and radio-resistance and the intrinsic ability of the malignant cells to disperse widely through normal brain tissue, making complete surgical resection nearly impossible. Therefore, finding new therapeutic markers and better understanding of the pathway related to cancer progression is warranted to promote the prognosis of patients with glioma, and possibly find a cure.

High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), an emerging method to study the RNA regulation mechanism in the whole genome, has been able to detect circular RNA (circRNAs) [4]. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a large class of endogenous RNAs that are formed by exon skipping or back-splicing events with neither 5’ to 3’ polarity nor a polyadenylated tail; however, they attracted little attention until their function in post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression was discovered. CircRNAs are conserved and stable, and numerous circRNAs seem to be specifically expressed in a cell type or developmental stage [5,6]. The cell type- or developmental stage-specific expression patterns indicate that circRNAs may play important roles in the regulation of multiple diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and cancerous tumors [7,8].

It’s reported that circRNAs play a vital role in many aspects of malignant phenotypes, including cell cycle, apoptosis, vascularization, and invasion, and metastasis [9-11]. With regard to their ways of function, circRNAs mainly serve as miRNA sponges to regulate gene expression, such as ciRS-7 [12]. Recently, several studies reported that circle RNA ITCH (cir-ITCH) is a circular RNA that spans several exons of Ubiquitin (Ub) protein ligase (E3) (ITCH) [13-15]. They indicated that cir-ITCH exerted inhibitory effect in hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through harboring many miRNA binding sites that can bind to the 3’-UTR of ITCH, which degrades the phosphorylated form of disheveled (Dvl) via the proteasome pathway, thus inhibiting the action of the canonical Wnt pathway. However, the functional role of cir-ITCH in glioma is not reported.

In this study, we hypothesized that cir-ITCH might regulate the expression level of ITCH mRNA and involve in glioma development. To verify this hypothesis, we detected the expression of cir-ITCH in primary tumor tissues and different glioma cell lines. Moreover, the functional relevance of cir-ITCH with glioma was further examined by gain and loss functional assays.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Sixty cancer tissues and paired adjacent noncancerous tissues from primary glioma patients were collected. All the patients were pathologically confirmed and the tissues were collected immediately after they were obtained during the surgical operation, and then stored at -80°C to prevent RNA loss. They were classified according to the WHO criteria and staged according to the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification. OS was updated on 1 February 2012 and was defined as the time from inclusion to death for any reason. RFS was defined as the time from inclusion to recurrence or metastasis progression. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients according to the guidelines approved by the Ethics Committee.

Cell culture

Human glioma cell lines (U87, U251, A172, SHG44, LN229, T98G and SHG139) and normal glial cell line M059K were purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Life Sciences Cell Resource Center (Shanghai, China). All glioma cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Biowest, France). Normal glial cell line M059K were grown in DMEM/F12 1:1 medium with 10% FBS, 2.5 mM L-glutamine adjusted to contain 15 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 1.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate supplemented with 0.05 mM non-essential amino acids. Cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% air.

RNA oligoribonucleotides and cell transfection

The cir-ITCH overexpression plasmid (p-cirITCH), miR-214 mimics, and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that specifically target ITCH (si-ITCH) was synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). For the construction of p-cirITCH, a 996 bp DNA fragment corresponding to exons 6-13 of the ITCH gene was used, and we added 1 kb upstream and 200 bp downstream to the nonlinear splice sites. Also, an 800-bp DNA stretch was added upstream of the splice acceptor site and inserted downstream in the reverse orientation. The cDNA sequence of cir-ITCH was synthesized by the Ribo Bio Company (Guangzhou, China) and then cloned into the lentiviral expression vector pLVXIRES-neo, (Clontech Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA). Lentiviral production and transduction were conducted by following previously published procedures [16]. Glioma cells were maintained in a 6-well plate in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and cultured until 50-70% confluent. RNA oligoribonucleotides were mixed with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in reduced serum medium (Opti-MEM, Gibco, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and final concentration of RNA oligoribonucleotides was 100 nM. Knockdown or overexpression effect was examined by RT-qPCR using RNA extracted 48 hours after transfection.

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from primary glioma tissues or cell lines using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). And then, the cDNA was synthesized from 200 ng extracted total RNA using the SuperScript III® (Invitrogen) and amplified by RT-qPCR based on the TaqMan method on an ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), with the housekeeping gene GAPDH or U6 as an internal control. The 2-ΔΔCt method was used to determine the relative quantification of gene expression levels. All the premier sequences were synthesized by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China), and their sequences are shown as follows: cir-ITCH (Forward) 5’-GCAGAGGCCAACACTGGAA-3’, (Reverse) 5’-TCCTTGAAGCTGACTACGCTGAG-3’; linear ITCH (Forward) 5’-TAGACCAGAACCTCTACCTCCTG-3’, (Reverse) 5’-TTAAACTG CTGCATTGCTCCTTG-3’; miR-214 (Forward) 5’-GACAGCAGGCACAGACA-3’, (Reverse) 5’-GTGCAGGGTCCGAG-3’; c-Myc (Forward) 5’-TTCGGGTAGTGGAAAACCAG-3’, (Reverse) 5’-CAGCAGCTCGAATTTCTTCC-3’; cyclin D1 (Forward) 5’-GAGGAGCAGCTCGCCAA-3’, (Reverse) 5’-CTGTCAAGGTCCGGCCAGCG-3’; GAPDH (Forward) 5’-GAAGGTGAAGGTC GGAGTC-3’, (Reverse) 5’-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3’.

MTT assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated by using 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenylt etrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma, MO, USA). Briefly, 5×103 cells per well were seeded into a 96-well plate. After transfection, the optical density was measured at 450 nm using a microtiter plate reader at different time points, and the rate of cell survival was expressed as the absorbance.

FACS apoptosis assay

Cells (1×105/well) were collected 48 h after transfection, and were stained with Annexin V FITC and propidium iodide (PI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium). Apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur).

Colony formation assays

HepG2 and Bel7404 cells were infected with Lv-cirITCH and cultured for 72 hours, and then they were re-plated in 6-well plates at the density of 5×102 per well and maintained for 10 days. The colonies were fixed and stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 15 minutes.

Cell migration and invasion assay

Cell migratory ability was detected by wound-healing assay. Briefly, transfected/treated cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured to near confluence. Artificial wounds were created on the cell monolayer using culture inserts for live cells analysis, and then migrated cells and wound healing were visualized. For each group, at least 3 artificial wounds were photographed immediately and at the time points indicated after the wound formation. After the wounds were created, the cells were incubated in culture medium without FBS and then photographed at 48 h. Percent of wound closure was calculated with Image J 1.47 software.

Cell invasive ability was detected by using Transwell permeable supports (Corning, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the transfected/treated cells were plated onto a Matrigel-coated membrane in the upper chamber of a 24-well insert containing medium free of serum. The bottom chamber contained DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 h after plating. Then, the bottom of the chamber insert was fixed with methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 15 minutes. The number of cells that invaded through the membrane was determined from digital images captured on an inverted microscope and calculated with Image J 1.47 software.

circRNAs immunoprecipitation (circRIP)

Biotin-labeled cir-ITCH probe (5’-CCGTCCGGAACTATGAACAACAATGGCA-3’-biotin) was synthesized by Sangon Biotech and the circRIP assay was performed as previously described with minor modification [11caoxuetao]. U87 cells were fixed by 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes, lysed and sonicated. After centrifugation, 50 µl of the supernatant was retained as input and the remaining part was incubated with cir-ITCH specific probes-streptavidin dynabeads (M-280, Invitrogen) mixture over night at 30°C. Next day, M-280 dynabeads-probes-circRNAs mixture was washed and incubated with 200 µl lysis buffer and proteinase K to reverse the formaldehyde crosslinking. Finally, the mixture was added with TRizol for RNA extraction and RT-qPCR detection. The RIP experiment using ITCH antibody (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biote-chnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) to pull down miR-214 was also performed. The Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA and controls were also assayed to demonstrate that the detected signals were from RNAs specifically binding to ITCH. The final analysis was performed using RT-qPCR and shown as the fold enrichment of miR-214.

Western blot and antibodies

Glioma cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma, MO, USA) containing protease inhibitors (Sigma). Protein quantification was done using a BCA protein assay kit (Promega, USA). The primary antibodies used for western blotting were rabbit anti-human Wnt3a antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), rabbit antihuman β-catenin antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-human β-actin antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), and rabbit anti-human ITCH antibody (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (HRP) anti-rabbit antibodies (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used as the secondary antibodies. A total of 25 μg protein from each sample was separated on 10% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel through electrophoresis and then blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Then, the membrane was blocked with 5% (5 g/100 mL) nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) in tri-buffered saline plus Tween (TBS-T) buffer for 2 h. Blots were immunostained with primary antibody at 4°C overnight and with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Immunoblots were visualized using ImmobilonTM Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore). Protein levels were normalized to β-actin.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Glioma cells were grown to 40% to 50% confluence and then transfected with 100 nM of p-cirITCH, miR-214 mimics or si-ITCH accordingly. After 48 hours of incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 minutes. The cells were then blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS for 1 h. Cells were incubated with primary anti-Ki-67 (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C and then incubated with the appropriate rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. The cells were then washed and incubated with DAPI (Invitrogen) for nuclear staining. The slides were visualized for immunofluorescence with a laser scanning Olympus microscope.

Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of the distribution of data in each group. For CRC vs. normal cell lines, and CRC tissue vs. adjacent non-tumor tissue, differences were shown in median expression and were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test. The correlation analysis was evaluated by using the Spearman test. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and area and the curve (AUC) was used to determine the diagnostic value of cir-ITCH. Count dates were described as frequency and examined using Fisher’s exact test. A log-rank test was used to analyze the statistical differences in survival as deduced from Kaplan-Meier curves. The results were considered statistically significant at P<0.05. Error bars in figures represent SD (Standard Deviation). Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (version 5.01, La Jolla, CA, USA) software. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Results

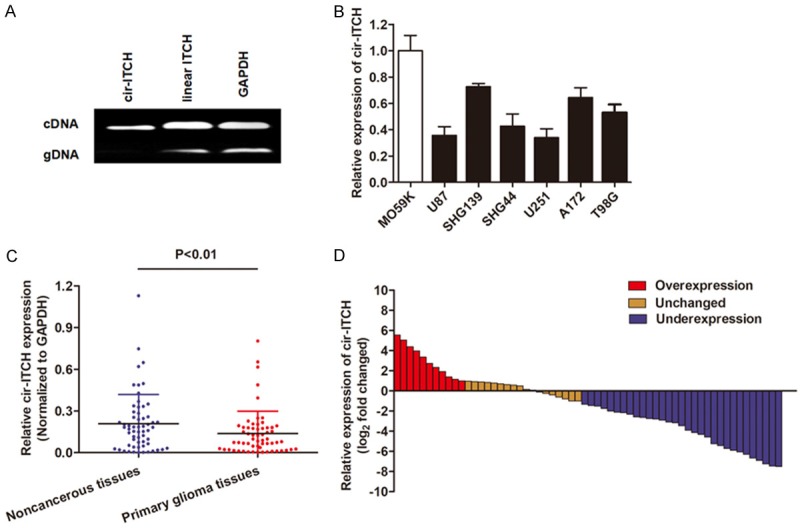

Cir-ITCH expression is downregulated in glioma

To investigate circRNAs expression in glioma tissues, we performed RT-qPCR assays to verify the circular form of ITCH. Two sets of ITCH primers were designed for this study: a divergent set that was expected to amplify only the circular form and an opposite directed set to amplify the linear forms. As expected, the circular form was amplified by using the divergent primers, and no amplification was observed when cDNA and genomic DNA were used as templates (Figure 1A). GAPDH was used as a linear control. Thus, we confirmed that cir-ITCH is specifically amplified with divergent primers on cDNA.

Figure 1.

The expression level of cir-ITCH is closely related to glioma. A. Divergent primers amplify circular RNAs in cDNA but not genomic DNA (gDNA). Convergent primers can amplify both circular RNAs and linear RNAs, GAPDH is linear control. B. Taq-man based RT-qPCR showed that cir-ITCH is downregulated in most glioma cell lines in contrast to human normal glial cell line M059K. C. cir-ITCH was also downregulated in primary glioma tissues when compare with adjacent noncancerous tissues. D. cir-ITCH expression level was analyzed in 60 primary glioma tissues and expressed as log2 fold change (glioma/normal), and the log2 fold changes were presented as follows: <1, underexpression (31 cases); >1, overexpression (11 cases); the remainder were defined as unchanged (18 cases).

Then, we detected the expression level of cir-ITCH in glioma cells. The TaqMan-based RT-qPCR showed that cir-ITCH was significantly downregulated in most glioma cell lines when compared to human normal glial cell line M059K (Figure 1B). A similar result was also observed when cir-ITCH was determined in glioma tissues and normal tissues (Figure 1C). Moreover, the glioma tissues in 51.6% (31 of 60) of cases had at least two-fold lower expression of cir-ITCH compared with noncancerous tissues (Figure 1D). We further determined the correlation between cir-ITCH expression and clinical pathological factors. The related demographic and clinicopathological information was retrospectively obtained from patient medical records. As shown in Table 1, cir-ITCH was significantly associated with several factors, including tumor size, WHO grade and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS). However, no significant correlations were observed between ITCH expression and other clinicopathological factors, such as gender, age, and weight loss.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 60 glioma patients and the expression of cir-ITCH

| Characteristics | Case | Cir-ITCH Median (range) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.880 | ||

| Male | 33 | 0.27 (0.01-1.13) | |

| Female | 27 | 0.24 (0.02-0.86) | |

| Age (years) | 0.259 | ||

| <60 | 28 | 0.19 (0.03-0.72) | |

| ≥60 | 32 | 0.28 (0.01-1.13) | |

| Tumor size | 0.020 | ||

| <5 cm | 35 | 0.12 (0.04-1.09) | |

| ≥5 cm | 25 | 0.27 (0.06-1.13) | |

| WHO grade | <0.001 | ||

| I | 11 | 0.08 (0.01-0.65) | |

| II | 8 | 0.17 (0.08-0.78) | |

| III | 17 | 0.25 (0.07-1.09) | |

| IV | 24 | 0.39 (0.16-1.13) | |

| KPS | 0.017 | ||

| <90 | 42 | 0.16 (0.01-0.93) | |

| ≥90 | 18 | 0.31 (0.05-1.13) | |

| Weight loss | 0.054 | ||

| <3 kg | 25 | 0.26 (0.01-1.06) | |

| ≥3 kg | 35 | 0.15 (0.02-1.13) |

KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status.

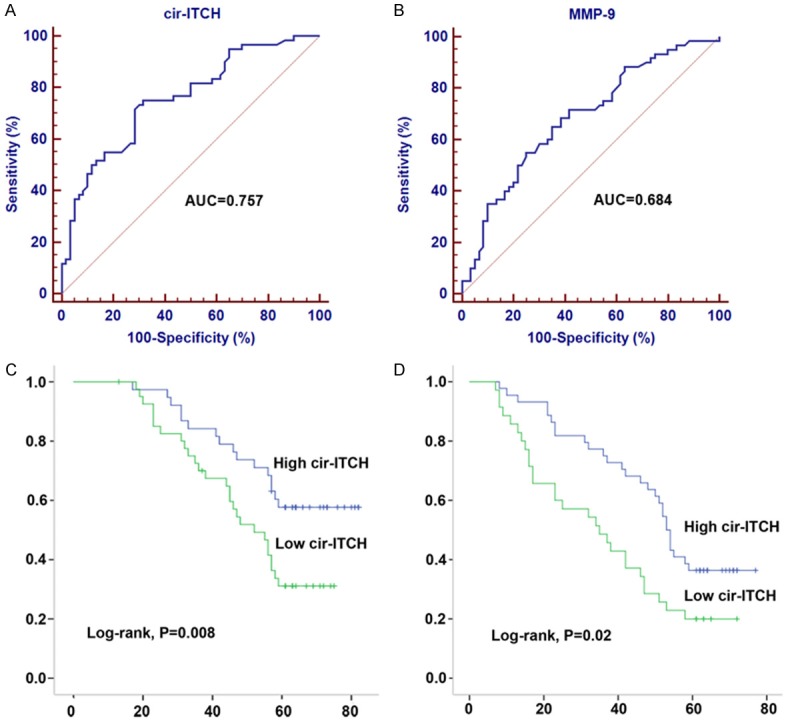

Decreased cir-ITCH expression is associated with poor prognosis of glioma patients

After having identified the downregulation of ITCH in glioma tissues. We further investigated its clinical diagnostic value. Receiver operation curve (ROC) analysis showed that area under the ROC curve (AUC) of ITCH was 0.757 (95% CI: 0.670-0.830) and the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity reached 75.00% and 68.33%, respectively (Figure 2A). We also determined the diagnostic value of the common used biomarker for glioma, MMP-9. We found that the AUC of MMP-9 was 0.684 (95% CI: 0.593-0.766), and diagnostic sensitivity and specificity were 71.67% and 58.33%, respectively (Figure 2B). The AUC of cir-ITCH was higher than MMP-9, suggesting a relatively high diagnostic efficacy of cir-ITCH for glioma patients.

Figure 2.

Decreased cir-ITCH expression is associated with poor prognosis of glioma patients. (A, B) ROC curve analysis was performed to investigate the diagnostic value of cir-ITCH (A) and MMP-9 (B) for glioma patients. (C, D) Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival (C) and progressive-free survival (D) were drawn according to cir-ITCH expression in 60 primary glioma tissues and were analyzed by using log-rank test.

On the basis of the cut-off established by the ROC analysis (0.36), we divided the 60 patients into a high-ITCH expressing group and a low-ITCH expressing group. Kaplan-Meier survival curve showed that patients in the low-ITCH expressing group was significantly correlated with poor overall survival (OS) and progressive-free survival (PFS) (Figure 2C and 2D). Furthermore, we performed Cox regression univariate/mutivariate analysis to identify whether cir-ITCH was an independent indicator for OS of glioma patients. As shown in Table 2, ITCH expression level and WHO grade maintained their significance as independent prognostic factors for OS of glioma patients.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model analysis of OS in glioma patients

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Gender | 1.031 | 0.682-3.090 | 0.378 | |||

| Age | 1.491 | 0.698-3.652 | 0.112 | |||

| Tumor size | 1.433 | 0.701-2.999 | 0.330 | |||

| KPS | 2.042 | 1.018-3.731 | 0.034 | 2.409 | 1.301-4.502 | 0.060 |

| WHO grade | 3.683 | 1.459-7.762 | 0.032 | 3.630 | 1.490-7.558 | 0.033 |

| cir-ITCH | 3.381 | 1.132-4.569 | 0.008 | 2.326 | 1.204-5.431 | 0.007 |

KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status.

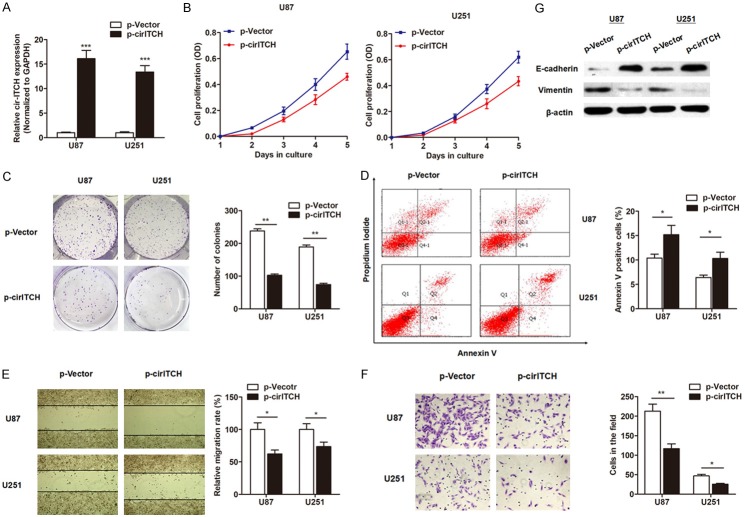

Cir-ITCH plays a tumor-suppressive role in glioma cells

To evaluate the functional role of cir-ITCH in glioma, we constructed the cir-ITCH overexpressing plasmid with circular frame and cir-ITCH sequence, and found cir-ITCH could be significantly overexpressed in U87 and U251 cells (Figure 3A). We then evaluated the role of cir-ITCH on cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion. MTT assay showed that overexpression of cir-ITCH significantly suppressed cell proliferation when compared with control vector in both cell lines (Figure 3B). Similarly, enhanced expression of cir-ITCH decreased the number of formed colonies, and promoted the number of apoptotic cells (Figure 3C and 3D). In addition, cir-ITCH significantly inhibited the wound healing ability of glioma cells (Figure 3E). Matrigel invasion assay showed that upregulation of cir-ITCH noticeably suppressed invasive and migratory capabilities of glioma cells (Figure 3F). Finally, we determined whether cir-ITCH regulated EMT process. As expected, E-cadherin protein was significantly upregulated while vimentin proteins were inhibited in glioma cells overexpressed with cir-ITCH (Figure 3G). Collectively, we demonstrated that cir-ITCH plays a tumor-suppressive function in glioma cells.

Figure 3.

cir-ITCH plays an anti-oncogenic role in glioma cells. (A) cir-ITCH was dramatically upregulated in glioma cells by transfection with cir-ITCH overexpression plasmid. (B) MTT assay was performed to evaluate the effect of cir-ITCH on cell proliferation, and enhanced cir-ITCH significantly suppressed cell viability in both U87 and U251 cells. (C) Colony formation assay showed that overexpression of cir-ITCH inhibited the colony formation capacity of glioma cells. (D) FACS apoptosis assay showed that cir-ITCH promoted the number of apoptotic glioma cells. (E, F) Wound healing assay (E) and Matrigel invasion assay (F) showed that cir-ITCH suppressed the migratory and invasive abilities of glioma cells, respectively. (G) Western blotting suggested that cir-ITCH promoted E-cadherin protein expression, but suppressed vimentin protein level. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

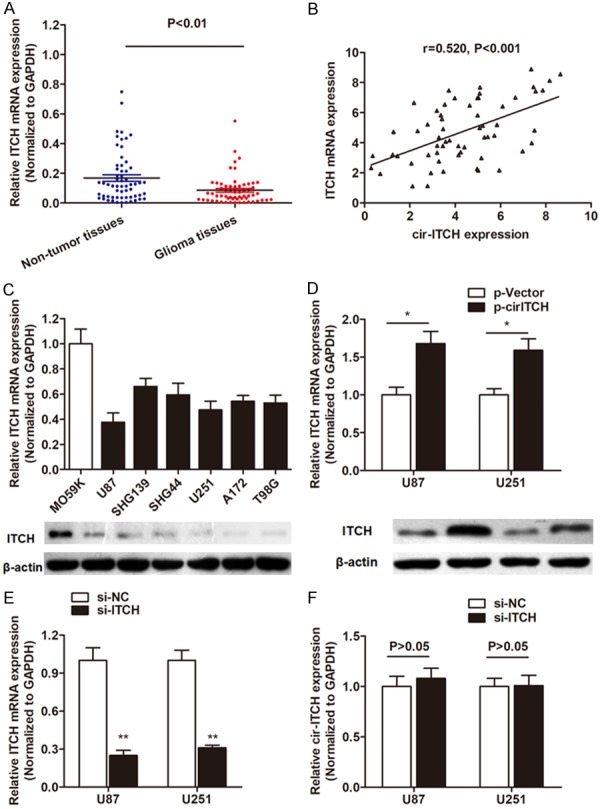

Cir-ITCH positively regulates ITCH gene expression in glioma cells

To investigate the underlying regulatory mechanism of cir-ITCH in glioma, we focus on the potential downstream target. It is reported that cir-ITCH is aligned in a sense orientation to the known protein-coding gene, ITCH, a member of the E3 ubiquitin ligases and commonly functions as a tumor-suppressor gene [13-15]. Hen-ce, we hypothesized that cir-ITCH might exerts its tumor-suppressive role through promoting the function of its linear isomer ITCH. We detected the expression of of ITCH mRNA expression, and found that ITCH mRNA was downregulated in the same cohort of glioma tissues (Figure 4A). More importantly, Spearman correlation analysis suggested that cir-ITCH was positively correlated with ITCH mRNA expression (Figure 4B). In addition, ITCH was also downregulated in glioma cell lines at both transcript and protein level (Figure 4C). More importantly, ITCH was dramatically upregulated in glioma cells after transfection of cir-ITCH overexpression vector (Figure 4D). However, knockdown of ITCH showed no significant effect on cir-ITCH expression (Figure 4E and 4F). These suggest that cir-ITCH positively regulate ITCH expression in a non-reciprocal way.

Figure 4.

cir-ITCH positively regulates the expression level of linear isomer ITCH. A. RT-qPCR showed that ITCH mRNA was significantly downregulated in primary glioma tissues compared with noncancerous tissues. B. Spearman correlation testing suggested that cir-ITCH expression was positively correlated with ITCH mRNA expression level. C. Both transcript and protein level of ITCH was downregulated in most glioma cells lines compared to normal glial cell line M059K. D. Linear ITCH gene was upregulated at both mRNA and protein level by transfection with cir-ITCH overexpression vector in both glioma cell lines. E. Linear ITCH level was dramatically silenced by transfection with specific siRNA. F. cir-ITCH was not influenced by ITCH gene. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

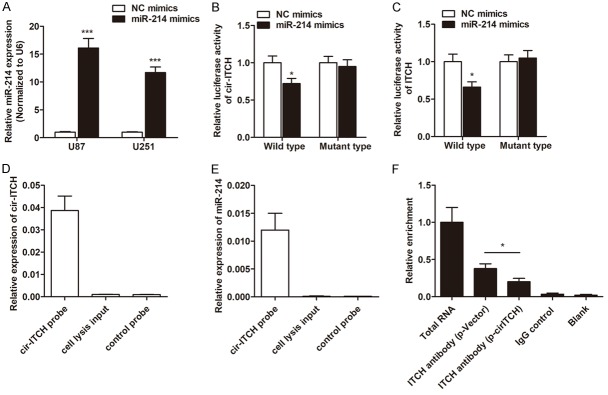

Cir-ITCH directly binds to miR-214, which promotes ITCH expression in glioma cells

It is identified that circRNAs function mainly as miRNA sponges to bind functional miRNAs and then regulate gene expression, we next examined the potential miRNAs associated with cir-ITCH. By using miRanda (http://www.microrna.org/) and TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/), we identified several miRNAs that contains complementary sequence to both cir-ITCH and 3’-UTR region of ITCH, including miR-216b, miR-17, miR-214, miR-7, and miR-128 (Table 3). Subsequently, luciferase reporter assay was performed to find the miRNA(s) that directly interacted with cir-ITCH and ITCH. As shown in Figure 5A, miR-214 was significantly upregulated in glioma cells transfected with miR-214 mimics. Co-transfection experiments showed that cells transfected with miR-214 had significantly inhibited luciferase activity of wild type reporter for both cir-ITCH and ITCH, however, miR-214 did not inhibit the luciferase activity of reporter vector containing the mutant binding sites of cir-ITCH or ITCH (Figure 5B and 5C), while the other four miRNAs showed no significant difference (date not shown). Take a step further, we used cir-ITCH specific probe to perform RNA precipitation (RIP), to validate that miR-214 actually binding with cir-ITCH. We purified the cir-ITCH-associated RNAs by cir-ITCH specific probe, and then screened the miRNAs that were pulled down by cir-ITCH with RT-qPCR assay. As expected, we found a specific enrichment of cir-ITCH and miR-214 as compared to the controls in U87 cells (Figure 5D and 5E), while the other miRNAs showed no enrichment (date not shown), indicating that cir-ITCH specifically interacts with miR-214 in glioma cells. Furthermore, we determined whether the sponge of miR-214 by cir-ITCH released ITCH. RIP experiment was performed and the results showed that the enrichment of ITCH and miR-214 was significantly decreased in glioma cells transfected with p-cirITCH (Figure 5F). Taken together, we revealed that cir-ITCH specifically sponged miR-214, which released ITCH expression.

Table 3.

The sequence of the predicted miRNA binding sites on the 3’UTR region of ITCH and cir-ITCH

| microRNA | miRNA binding sites 3’UTR | miRNA binding sites in cir-ITCH |

|---|---|---|

| miR-17 | CAUUAUUAACUGAUUAAUGCACUUUG | CAAAGUGCUUACAGUGCAGGUAG |

| miR-7 | GUGGCCACAUGUAUAUGUCUUCCC | UGAGGUAGUAGGUUGUAUAGUU |

| miR-214 | UGUAUAUGUCUUCCCUGCUGU | ACAGCAGGCACAGACAGGCAGU |

| miR-216b | CCUACAAUAUUUACUAGAGAUUU | AAAUCUCUGCAGGCAAAUGUGA |

| miR-128 | UACAAACAAUGUUAACACUGUGA | UCACAGUGAACCGGUCUCUUU |

Figure 5.

Cir-ITCH directly binds to miR-214, which promotes ITCH expression in glioma cells. A. miR-214 was overexpressed by transfection with miR-214 mimics. B. Luciferase reporter assay showed that miR-214 targets the wild-type but not the mutant cir-ITCH in U87 cells. C. MiR-214 targets the wild-type but not the mutant 3’UTR of ITCH in U87 cells. D. cir-ITCH in U87 cell lysis was pulled down and enriched with cir-ITCH specific probe and then detected by RT-qPCR. E. miR-214 in U87 cell lysis was pulled down and enriched with cir-ITCH specific probe and then detected by RT-qPCR. F. RIP experiments were performed using the ITCH antibody to immunoprecipitate RNA and a primer to detect miR-214, and a significantly decreased enrichment of miR-214 was identified in cells transfected with p-cirITCH compared with p-Vector. *, P<0.05; ***, P<0.001.

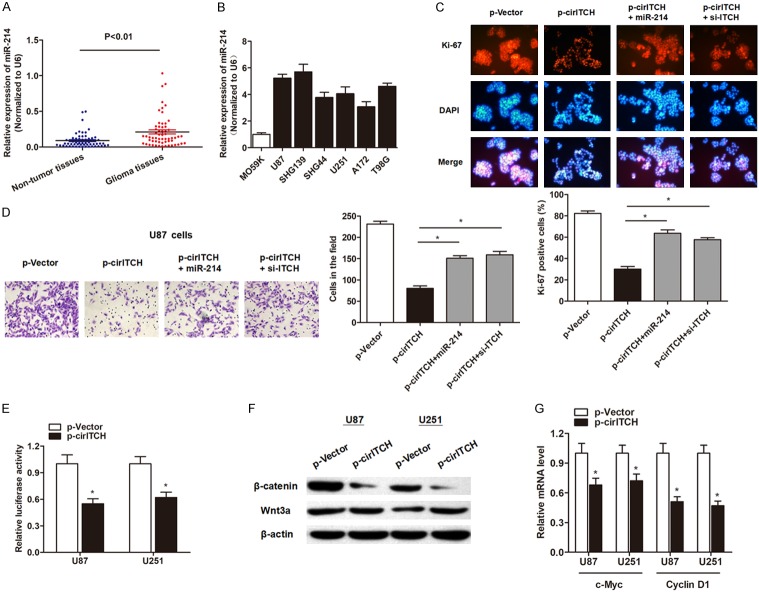

Cir-ITCH suppresses cell proliferation and invasion through sponging miR-214 and promoting ITCH in glioma

We sought to determine the functional mechanism of cir-ITCH in glioma cells. RT-qPCR showed that miR-214 was significantly upregulated in primary glioma tissues and cell lines (Figure 6A and 6B). To investigate the role of miR-214 and ITCH during cir-ITCH mediated anti-oncogenic function, we performed gain and loss functional assays by cotransfection of specific miR-214 mimics and ITCH siRNAs. As expected, the results indicated that the inhibited capacities of cell proliferation and invasion induced by cir-ITCH overexpression was partially reversed by co-transfection of miR-214 mimics or si-ITCH (Figure 6C and 6D). As ITCH is involved in the regulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway, we determined the effect of cir-ITCH on the regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The β-catenin/T-cell factor (TCF) responsive luciferase reporter assay showed that overexpression of cir-ITCH suppressed TCF transcriptional activity in glioma cells (Figure 6E). Western blot experiments showed that cir-ITCH significantly suppressed the protein level of β-catenin, while no change in Wnt3a expression was shown (Figure 6F). Furthermore, the downstream target of β-catenin, c-Myc and Cyclin D1 mRNA was also significantly suppressed by cir-ITCH (Figure 6G). To conclude, cir-ITCH exerts its anti-oncogenic role in glioma through sponging miR-214 and releasing ITCH.

Figure 6.

Cir-ITCH suppresses cell proliferation and invasion through sponging miR-214 and promoting ITCH in glioma. A. RT-qPCR showed that miR-214 was upregulated in glioma tissues in contrast to adjacent normal tissues. B. miR-214 was upregulated in most of the glioma cell lines when compared with human normal glial cell line M059K. C. Immunofluorescence analysis by using Ki-67 antibody indicated that the cir-ITCH suppressed of the expression level of cell proliferation marker Ki-67 in U87 cells; however, this effect was partially reversed by co-transfection with miR-214 mimics and si-ITCH. D. Co-transfection with miR-214 mimics or si-ITCH reversed the cir-ITCH-induced suppression of invasive capacity in U87 cells. E. U87 and U251 cells were transfected with cir-ITCH or empty control vector; then, a TCF responsive luciferase reporter assay was performed. The luciferase activity was normalized to the Renilla luciferase activity. F. The protein levels of Wnt3a and β-catenin were assessed in U87 cells and U251 cells by western blotting. G. The mRNA level of c-Myc and Cyclin D1 in U87 and U251 cells were detected by RT-qPCR after being transfected with cir-ITCH or empty control vector. *, P<0.05.

Discussion

Despite the rapid development of early diagnosis and treatment in glioma, invariably, nearly all glioma patients finally become chemoresistant and metastatic [17]. It is widely accepted that searching new therapeutic targets and better understanding the pathway related to cancer initiation and progression is essential for improving the prognosis of glioma patients. In this study, we focused on a novel gene regulator, circRNA, and validated the downregulation of cir-ITCH in glioma tissues and cells. Further, we also uncovered that the decreased expression of cir-ITCH was a potential diagnostic and prognostic factor for glioma patients. Mechanistic analysis indicated that cir-ITCH suppressed the capacity of proliferation, migration and invasion of glioma cells. More importantly, we found that cir-ITCH plays a tumor-suppressive role through specifically sponging miR-214 and releasing ITCH.

The concept of “circular RNA” was first proposed in 1976, Sanger and colleagues found that viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circRNA molecules pathogenic to certain higher plants [18]. With the development of gene investigations, it is recognized that circRNAs are widely expressed in human cells, and their expression levels can be 10-fold or higher compared to their linear isomers [5]. The two most important properties of circRNAs are highly conserved sequences and a high degree of stability in mammalian cells [19]. Compared with other noncoding RNA, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), these properties provide circRNAs with the potential to become ideal biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of cancers [20,21]. To date, only a few circRNAs have been explored. Here, we identified a novel circular RNA termed cir-ITCH that was significantly downregulated in glioma specimens and correlated with clinical prognosis. Cir-ITCH is a circRNA that spans several exons of the itchy E3 ubiquitin protein ligase gene (ITCH), which is reported to be downregulated and involved in the regulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer and lung cancer [13-15]. Although the expression of cir-ITCH was validated in these cancers by TaqMan quantitative realtime RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) systems, further functional studies were not carried out.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the expression and functional role of cir-ITCH in glioma. Consistent with previous reports, we revealed that cir-ITCH is significant downregulated in glioma tissues and cell lines. Furthermore, decreased cir-ITCH expression is associated with clinical stages, high diagnostic accuracy, and correlated poor survival of glioma patients. As circRNAs are a class of endogenous RNAs featuring stable structure making them avoid exonucleolytic degradation by RNase R, cir-ITCH may serve a novel biomarker used for early diagnosis, treatment monitoring and prognosis for glioma patients [22]. Take a step further, we sought to determine the underlying mechanism that may account for the clinical findings. Cell functional assays clearly showed that cir-ITCH suppressed cell proliferation, migration and invasion capacity, but promoted the number of apoptotic cells of glioma. To further investigate how cir-ITCH exerts these functions, we detected the expression of the linear isomer of cir-ITCH, and found that ITCH was significantly upregulated in human glioma tissues and cell lines. Moreover, a positive correlation of cir-ITCH and ITCH expression was identified, indicating that cir-ITCH may serve as a tumor-suppressor gene through promoting ITCH in glioma.

MiRNAs, an abundant class of small noncoding RNAs (~22 nt), posttranscriptionally modulate the translation of target mRNAs via corresponding miRNA response elements (MRE) [23]. Computational searches for miRNA target sites in circRNAs identified a portion of circRNA molecules that contain MREs, which might act as miRNA sponge, reducing miRNA binding to its target genes, thereby releasing the expression of the miRNA targets indirectly [6,24-26]. Since the first report of circRNA functioning as a miRNA sponge, the potential of circRNAs in regulating cancer-related genes through fine-tuning miRNAs has recently been recognized. For example, the first characterized circRNA to support this model is ciRS-7, which contains more than sixty miR-7-binding sites, thereby acting as an endogenous miRNA sponge to adsorb and subsequently quench normal miR-7 functions [27,28]. More recently, more and more circRNAs were recognized as miRNA sponges in different cancers, such as colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma [29-31]. However, this model reported in glioma is very limited. Zheng et al reported that circ-TTBK2 promotes glioma progression by regulating miR-217/HNF1b/Derlin-1 pathway [32]; Nair et al revealed that ciRS-7 is downregulated in glioma and negatively correlated with miR-671-5p expression [33]. In this study, we identified several miRNAs that showed complementary sequence to both cir-ITCH and 3’-UTR region of ITCH through bioinformatic analysis, and miR-214 was finally identified as the endogenous competing RNA by luciferase reporter assay and RIP assay. Moreover, the sponge of cir-ITCH to miR-214 significantly released the targeted silence of ITCH by miR-214. Hence, this is the first report to identified miR-214 as a sponged miRNA by cir-ITCH, which enhanced the depth of the research into cir-ITCH in glioma.

After having established the regulatory model of cir-ITCH/miR-214/ITCH, we determined to verify whether cir-ITCH play an anti-oncogenic role through sponging miR-214 and activating ITCH. As expected, miR-214 overexpression or ITCH knockdown inhibited capacities of cell proliferation, migration and invasion induced by cir-ITCH. In addition, cir-ITCH also suppressed the expression of Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which further validated its effect on miR-214 and ITCH. In conclusion, we reported that cir-ITCH is downregulated and predicts poor survival in glioma patients. Moreover, cir-ITCH acts as a tumor-suppressor gene through sponging miR-214 and thereby promoting the function of ITCH.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Bin Xia in Chinese Medical University for his great contribution to their study. This study was supported by the natural science foundation of Jilin Province (JL2015K23A05).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Taylor LP. Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of glioma: five new things. Neurology. 2010;75:S28–32. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fb3661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y, Liu F, Xu Q, Wang X. Analysis of the expression profile of Dickkopf-1 gene in human glioma and the association with tumor malignancy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:138. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorek R, Cossart P. Prokaryotic transcriptomics: a new view on regulation, physiology and pathogenicity. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:9–16. doi: 10.1038/nrg2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, Slevin MK, Burd CE, Liu J, Marzluff WF, Sharpless NE. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA. 2013;19:141–157. doi: 10.1261/rna.035667.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer M, Loewer A, Ziebold U, Landthaler M, Kocks C, le Noble F, Rajewsky N. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia W, Qiu M, Chen R, Wang S, Leng X, Wang J, Xu Y, Hu J, Dong G, Xu PL, Yin R. Circular RNA has_circ_0067934 is upregulated in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and promoted proliferation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35576. doi: 10.1038/srep35576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou B, Yu JW. A novel identified circular RNA, circRNA_010567, promotes myocardial fibrosis via suppressing miR-141 by targeting TGF-beta1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;487:769–775. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Mo Y, Gong Z, Yang X, Yang M, Zhang S, Xiong F, Xiang B, Zhou M, Liao Q, Zhang W, Li X, Li X, Li Y, Li G, Zeng Z, Xiong W. Circular RNAs in human cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:25. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0598-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Li J, Yu J, Liu H, Shen Z, Ye G, Mou T, Qi X, Li G. Circular RNAs signature predicts the early recurrence of stage III gastric cancer after radical surgery. Oncotarget. 2017;8:22936–22943. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu J, Ye J, Zhang L, Xia L, Hu H, Jiang H, Wan Z, Sheng F, Ma Y, Li W, Qian J, Luo C. Differential expression of circular RNAs in glioblastoma multiforme and its correlation with prognosis. Transl Oncol. 2017;10:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu H, Guo S, Li W, Yu P. The circular RNA Cdr1as, via miR-7 and its targets, regulates insulin transcription and secretion in islet cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12453. doi: 10.1038/srep12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang G, Zhu H, Shi Y, Wu W, Cai H, Chen X. cir-ITCH plays an inhibitory role in colorectal cancer by regulating the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan L, Zhang L, Fan K, Cheng ZX, Sun QC, Wang JJ. Circular RNA-ITCH suppresses lung cancer proliferation via inhibiting the wnt/betacatenin pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1579490. doi: 10.1155/2016/1579490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li F, Zhang L, Li W, Deng J, Zheng J, An M, Lu J, Zhou Y. Circular RNA ITCH has inhibitory effect on ESCC by suppressing the Wnt/betacatenin pathway. Oncotarget. 2015;6:6001–6013. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng J, Deng J, Xiao M, Yang L, Zhang L, You Y, Hu M, Li N, Wu H, Li W, Lu J, Zhou Y. A sequence polymorphism in miR-608 predicts recurrence after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5151–5162. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appin CL, Gao J, Chisolm C, Torian M, Alexis D, Vincentelli C, Schniederjan MJ, Hadjipanayis C, Olson JJ, Hunter S, Hao C, Brat DJ. Glioblastoma with oligodendroglioma component (GBM-O): molecular genetic and clinical characteristics. Brain Pathol. 2013;23:454–461. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanger HL, Klotz G, Riesner D, Gross HJ, Kleinschmidt AK. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3852–3856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK, Kjems J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P, Zhang X, Wang H, Wang L, Liu T, Du L, Yang Y, Wang C. MALAT1 is associated with poor response to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients and promotes chemoresistance through EZH2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:739–751. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li PL, Zhang X, Wang LL, Du LT, Yang YM, Li J, Wang CX. MicroRNA-218 is a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer and enhances 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis by targeting BIRC5. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:1484–1493. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeck WR, Sharpless NE. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:453–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao ZJ, Shen J. Circular RNA participates in the carcinogenesis and the malignant behavior of cancer. RNA Biol. 2017;14:514–521. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1122162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du WW, Yang W, Liu E, Yang Z, Dhaliwal P, Yang BB. Foxo3 circular RNA retards cell cycle progression via forming ternary complexes with p21 and CDK2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:2846–2858. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen TB, Wiklund ED, Bramsen JB, Villadsen SB, Statham AL, Clark SJ, Kjems J. miRNA-dependent gene silencing involving Ago2-mediated cleavage of a circular antisense RNA. EMBO J. 2011;30:4414–4422. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng L, Yuan XQ, Li GC. The emerging landscape of circular RNA ciRS-7 in cancer (Review) Oncol Rep. 2015;33:2669–2674. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen TB, Kjems J, Damgaard CK. Circular RNA and miR-7 in cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5609–5612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie H, Ren X, Xin S, Lan X, Lu G, Lin Y, Yang S, Zeng Z, Liao W, Ding YQ, Liang L. Emerging roles of circRNA_001569 targeting miR-145 in the proliferation and invasion of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:26680–26691. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulcheski FR, Christoff AP, Margis R. Circular RNAs are miRNA sponges and can be used as a new class of biomarker. J Biotechnol. 2016;238:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng Q, Bao C, Guo W, Li S, Chen J, Chen B, Luo Y, Lyu D, Li Y, Shi G, Liang L, Gu J, He X, Huang S. Circular RNA profiling reveals an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11215. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng J, Liu X, Xue Y, Gong W, Ma J, Xi Z, Que Z, Liu Y. TTBK2 circular RNA promotes glioma malignancy by regulating miR-217/HNF1beta/Derlin-1 pathway. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:52. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0422-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbagallo D, Condorelli A, Ragusa M, Salito L, Sammito M, Banelli B, Caltabiano R, Barbagallo G, Zappala A, Battaglia R, Cirnigliaro M, Lanzafame S, Vasquez E, Parenti R, Cicirata F, Di Pietro C, Romani M, Purrello M. Dysregulated miR-671-5p/CDR1-AS/CDR1/VSNL1 axis is involved in glioblastoma multiforme. Oncotarget. 2016;7:4746–4759. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]