Abstract

Suicide is a leading cause of death in adolescence. School provides an effective avenue both for reaching adolescents and for gatekeeper training. This enables gatekeepers to recognize and respond to at-risk students and is a meaningful focus for the provision of suicide prevention. This study provides the first systematic review on the effectiveness of school-based gatekeeper training in enhancing gatekeeper-related outcomes. A total of 815 studies were identified through four databases (Ovid Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and ERIC) using three groups of keywords: ‘school based’, ‘Suicide prevention programme’ and ‘Gatekeeper’. Fourteen of these studies were found to be adequate for inclusion in this systematic review. The improvement in gatekeepers’ knowledge; attitudes; self-efficacy; skills; and likelihood to intervene were found in most of the included studies. Evidence of achieving improvement in attitudes and gatekeeper behaviour was mixed. Most included studies were methodologically weak. Gatekeeper training appears to have the potential to change participants’ knowledge and skills in suicide prevention, but more studies of better quality are needed to determine its effectiveness in changing gatekeepers’ attitudes. There is also an urgent need to investigate how best improvements in knowledge and skills can be translated into behavioural change.

Keywords: Adolescents, Gatekeeper training, School-based, Suicide prevention, Systematic review

Background

Adolescent suicide as a significant public health issue

Suicide-related behaviour is common among school-aged adolescents. Globally, suicide is reported to be the second leading cause of death among young people aged 15–29 [1]. It is believed that the suicide rate is underreported in many countries due to inconsistent death classification systems, and the cultural and religious beliefs that may affect the coroner’s decisions [2, 3].

Associated factors and consequences of adolescent suicide

Adolescent suicide is a serious and complex public health problem which is associated with a range of interlocking factors. Facing the shift to middle school or high school, students have to adapt to a new environment in many aspects [4]. However, some adolescents are not mature enough to deal with this kind of life transition, leading to substance or alcohol abuse [4, 5], depression, unruly behaviour such as bullying and fighting or even expulsions by their schools [6]. These are all risk factors for suicidal behaviour. Also, conflicts with family members, relationship problems with close friends, and uncertainty about the future are identified as trigger points for suicidal behaviour [7]. The impact of losing a young life not only causes huge societal loss but also brings tremendous psychological suffering to their families [8]. Suicide may even create a copycat effect due to the sensational reporting by media, especially in Asia [9]. Interventions to prevent adolescent suicide-related behaviour are highly warranted.

Importance of school-based intervention in preventing adolescent suicide

Reducing adolescent suicide is a huge challenge in many countries. Many adolescents who have suicidal thoughts are not willing to seek help [10, 11]. They also avoid attending the treatment arranged for them [12], and are less likely to seek help from formal channels [13]. Although many suicide prevention programmes are available in the community, it is often difficult to reach those suicidal youths to provide resources and support. In view of these challenges, school-based programmes are recommended for adolescents as they can provide an easy on-going access to students [14]. As adolescents spend most of their time in school, school-based programmes are considered one of the most effective ways to address the problem of adolescent suicide and to promote help-seeking among adolescents [15].

Most school-based suicide prevention programmes fall into one of three categories. First, suicide awareness education curricula aims to increase students’ awareness of suicide, help students recognize the signs of suicide, and encourage self-disclosure [16]. One criticism of this approach, however, is that increasing students’ knowledge and awareness of suicide does not necessarily lead to behavioural change [17]. Second, peer leadership training programmes train students to help their suicidal peers by responding appropriately and referring them to a trusted adult [18]. However, a peer leader may not be able to approach their suicidal peers as those who have suicidal thoughts usually isolate themselves from the peer network, limiting the efficacy of the programme [18]. Third, screening programmes can help to identify at-risk students for suicide prevention [17]. A valid and reliable screening tool is important to prevent the potential iatrogenic effect. Review on suicide prevention programmes reported that limited evidence exists in suggesting that education and screening is effective in reducing suicide [19]. Furthermore, for those suicide prevention programmes that are found to be effective, most of them have their effects diminished over time.

Gatekeeper approach as a promising way for adolescent suicide prevention

More recently, the gatekeeper approach has been recognized as a promising way for adolescent suicide prevention. Gatekeepers are defined as “individuals in a community who have face-to-face contact with large numbers of community members as part of their usual routine”. The gatekeeper approach therefore aims to train those gatekeepers to identify individuals who are at-risk of suicide and refer them to health care professionals [20]. Gatekeeper training programmes are developed as many individuals who have suicidal ideation do not seek help, and that risk factors for suicide are recognizable and thus identifiable [18]. In a school setting, gatekeeper training is a widely disseminated strategy that trains gatekeepers to recognize signs of suicide, and enhances knowledge and attitudes to intervene with at-risk students [13]. Through the gatekeeper training programme, participants have the ability to respond appropriately and effectively to those at-risk students, so that early identification and referral to health professionals can be achieved [21]. Furthermore, gatekeeper training relies on outside service and stakeholders’ support, such as mental health services and treatment [22].

Some suicide prevention programmes are created under the gatekeeper training principles, for example, in the primary gatekeeper training programme, Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) [23], participants learn the suicidal warning signs, as well as the skills to assess at-risk students, to manage the situation appropriately and to refer them to health professionals for treatment if necessary. Although it has been identified as the best practice, a rigorous evaluation on this approach remains scarce [17]. Another prominent gatekeeper training programme, Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), is a 2 day interaction workshop for participants to gradually build comfort and understanding about suicide and suicide intervention [24].

Main participants of gatekeeper programme are school personnel, such as teachers, teaching staff, coaches and administrators. There is no doubt that adolescents spend most of their time in school every day. School personnel also play an important role on youth growth and have lots of opportunities to contact and interact with students. They can observe any abnormal behavior from students and offer them support. On the other hand, it has also been shown that most of the teachers feel uncomfortable and unprepared about addressing the topic of suicide. They report a lack of skills to respond when coping with students’ suicidal signs and behaviour [25, 26]. The gatekeeper approach is therefore a potentially effective method to increase their knowledge and skills in dealing with adolescents who are at-risk of suicide [27].

The gatekeeper approach is frequently used in attempts to reduce rates of adolescent suicide. The extent to which it is effective in achieving this, especially in a school-based setting, remains unclear [28]. Although there is evidence that gatekeeper training can improve the knowledge and attitudes of participants [29] and is recommended in school-based suicide prevention, some studies failed to demonstrate the effectiveness of this programme [30]. Increase in knowledge and attitude may not enable the school staff to effectively recognize and respond to some students’ suicidality without explicit warning signs. It was further argued that students with suicidal ideation are less likely to seek help through school personnel compared with other students, thus universal gatekeeper training that merely focused on the staff’s roles may not be sufficient for the success of suicide prevention [29]. A review to synthesize the evidence of school-based gatekeeper training for adolescent suicide prevention is warranted.

Aims

‘Despite its implementation in many settings, a systematic evaluation on the efficacy of this approach in adolescent suicide prevention is currently lacking [31]. With the different content and methods used in various studies, a systematic review can synthesize the findings and provide clear evidence on whether school-based gatekeeper training is an effective method of suicide prevention among adolescents. The current study aims to conduct a systematic review on the effectiveness of school-based gatekeeper training in enhancing gatekeepers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviour for adolescent suicide prevention.

Methods

Identification of relevant studies

Studies related to school-based gatekeeper training for adolescent suicide prevention were identified from four online databases, namely Ovid Medline (1946–2017 December 18), Embase (1910–2017 December 18), PsycINFO (1806–2017 December Week 2) and ERIC (1966–2017 December 19). The search was restricted to English articles and studies of all types, including journal articles, book chapters, and dissertations were included. Bibliographies of the included studies and a systematic review on gatekeeper training for suicide prevention [32] were also examined for further relevant studies.

A broad search strategy was employed and search keywords were categorized into three key terms: “school-based”, “suicide prevention programme”, and “gatekeeper”. To maximize the search in the databases, various synonyms and combinations of the search terms were used. Search terms for “school-based” included “school”, or “curriculum based”. Search terms for “Suicide prevention programme” included “suicide prevention”, “suicide education”, “self-harm prevention”, or “suicide intervention”. Search terms for “gatekeeper” included “gatekeeper”, “teacher”, “staff”, “personnel”, “counsellor”, “psychologist”, “Question, Persuade, Refer”, or “Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training”.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included for the review if they: (1) used a controlled trial (RCT) or quasi-experiment design; (2) primarily targeted suicide prevention; (3) used a gatekeeper approach for the intervention, in which more than 60% of the participants of the programme are school personnel who have face to face contact with students; (4) were based in middle school or high school; (5) had at least one outcome related to suicide prevention (see below section for details); and, (6) contained a comparison group or reported pre- and post-intervention data. No restrictions on the eligibility of studies were imposed on the basis of sample size, duration of follow-up, or publication source.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they were: (1) non-school based; (2) not related to suicide prevention; (3) general suicide prevention programmes without using a gatekeeper approach; (4) using peer as gatekeeper; (5) non-intervention based (e.g. qualitative studies, commentary, or review); (6) using a single group design with only post-intervention data reported; or (7) not written in English.

Study outcome

Various outcomes for suicide prevention training have been identified in the literature. Due to the low frequency of completed suicide and the difficulty in ascertaining suicide rate [25], reducing suicide rate should not be regarded as the key indicator for effectiveness of a suicide prevention programme [33]. In the context of gatekeeper training programmes for suicide prevention, the most common outcomes included increase in gatekeepers’ knowledge of suicide risk assessment and management, improvement in skills of observing any abnormal signs and dealing with at-risk individuals appropriately [34], increase in confidence in dealing with individuals who are at risk of suicide, and positive gains in attitude towards suicide. Gatekeeper behaviors related to intervening with suicidal individuals, such as speaking with students who are at risk of suicide, or referring students to mental health services, were also measured [35].

Based on the current literature of suicide prevention using a gatekeeper approach, the following gatekeeper-related outcomes were included in the review: knowledge about adolescent suicide, gatekeeper skills, attitudes towards adolescent suicide, self-efficacy, likelihood to intervene when a student has suicidal thoughts, and gatekeeper behaviours.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently reviewed and screened the articles. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Data were extracted using a coding scheme designed by the authors and the following information was coded: location of the study, sample characteristics, intervention characteristics, measures used, and outcomes. Effect size (Cohen’s d) was directly extracted or computed by using the raw data for each test [36]. For studies with a design of ‘controlled trial without a pre-test’ or ‘before- and after comparison’, Cohen’s d was estimated as the mean difference divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD), with an adjustment to unequal sample size as appropriate [37]. For studies with a design of ‘controlled trial with pre- and post-test’, the estimation was based on the pooled pre-test SD across intervention conditions [38]. If means and SDs were not available, other indices of effect size were extracted and converted to Cohen’s d (e.g. t, partial eta-squared) [36, 39]. An assessment of the quality of studies with comparison groups was also conducted. This included their use of randomized assignment, concealment methods, use of an intent-to-treat analysis, and whether the intervention deliverer was blinded to the study.

Results

Included studies

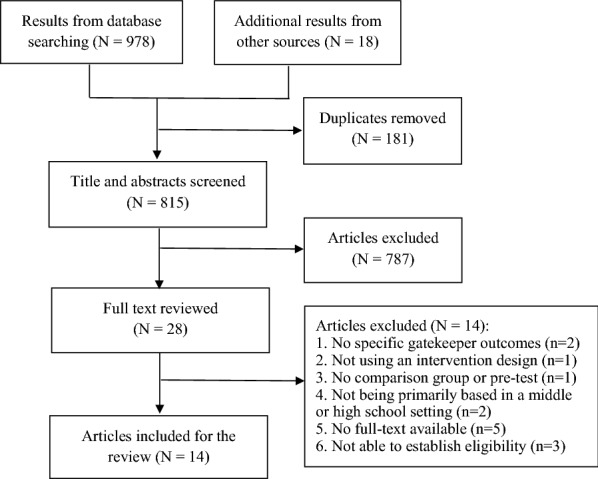

The database search identified 978 studies with a further 18 found through screening the bibliographies of the relevant literature; 181 of these were duplicate and thus removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 815 studies were screened; 28 of these were relevant to the study aims and retained for examination of the full text. Despite efforts to contact the authors for full text or more study details, these could not be obtained for five from any available source, and adequate information to establish study eligibility could not be obtained for three others. Finally, 14 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Fig. 1; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of screening process

Table 1.

Characteristics and main results of the studies included in the systematic review (N = 14)

| Participants | Intervention | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Location | Sample size | Sample type | Mean age | % of male | Name of the programme | Intervention group (INT) | Comparison group (COM) | Program duration and attrition rate at post-test3 | Follow-up duration and attrition rate at follow-up | Outcomes | Instruments | Main results |

| Controlled trials with pre- and post-test | |||||||||||||

| Cross et al. [13] | New York, United States | INT = 72 CON = 75 | School staff (N = 91) and parents (N = 56) | School staff = 42.07 (SD = 10.41) Parents = 43.49 (SD = 4.65) | School staff = 23.1% Parents = 5.4% | QPR | Gatekeeper training plus behavioral rehearsal | QPR | INT = 1 h 25 min; NA CON = 1 h; NA | 3 months | 1. Knowledge | Declarative knowledge: Adapted from previous studies [52, 53]; 14 items Self-perceived knowledge: Adapted from previous studies [52, 54, 55]; 5 items |

Significant increase in both groups at post-test (d = 0.61 for INT; d = 0.74 for COM) and maintained at follow-up (d = 0.57 for INT; d = 0.46 for COM); no group (d = − 0.11 at post-test; d = 0.12 at follow-up) or interaction effects were found Significant increase in both groups at post-test (d = 2.08 for INT; d = 2.01 for COM) and maintained at follow-up (d = 1.86 for INT; d = 1.63 for COM); no group (d = 0.18 at post-test; d = 0.27 at follow-up) or interaction effects were found |

| 2. Self-efficacy | Adapted from previous studies [52–55]; 5 items | Significant increase in both groups at post-test (d = 1.27 for INT; d = 1.34 for COM) and maintained at follow-up (d = 1.22 for INT; d = 1.48 for COM); no group (d = 0.16 at post-test; d = 0.07 at follow-up) or interaction effects were found | |||||||||||

| 3. Gatekeeper skills | Adapted from Observational Rating Scale of Gatekeeper Skills (ORS-GS) Scoring System [54, 55]; 5 items | Higher score in INT compared to COM at post-test (d = 0.46); no group difference at follow-up (d = 0.25) | |||||||||||

| 4. Gatekeeper behavior | Self-reported referrals: Self-developed items; 1 item | No difference between INT and COM at follow-up (d = 0.01) | |||||||||||

| Klingman [40] | Northern Israel | 30 | Teachers and counselors | NR | 0% | Gatekeeper training in group-oriented workshop format | Gatekeeper training in problem-oriented workshop format | 3 h; NR | NA | 1. Knowledge | General knowledge: Self-developed items, 13 items | Both groups scored significantly higher at post-test (d = 3.30 for INT; d = 3.63 for COM); no significant difference between groups (d = 0.00) | |

| Identification of warning signs: self-developed items, 12 items | Both groups scored significantly higher at post-test (d = 1.36 for INT; d = 1.53 for COM); no significant difference between groups (d = − 0.23) | ||||||||||||

| Knowledge about prevention: Self-developed items, 7 items | Both groups scored significantly higher at post-test (d = 1.59 for INT; d = 0.68 for COM); problem-oriented group showed significantly more knowledge than group oriented group (d = 0.68) | ||||||||||||

| 2. Self-efficacy | Personal competence: Self-developed items, 7 items | Both groups scored significantly higher at post-test (d = 1.04 for INT; d = 1.24 for COM); no significant difference between groups (d = − 0.15) | |||||||||||

| Tompkins et al. [21] | The pacific Northwest | INT = 106 CON = 35 | School personnel | NR | 22.6% | QPR | Gatekeeper training | No intervention | 1 h; 27.7% % | 3 months, 72.3% | 1. Knowledge | Knowledge of QPR: Adapted from previous studies; 15 items | Significant increase in INT compared to COM in at post-test (d = 1.52) but not maintained at follow-up (d = 0.46) |

| Self evaluation of knowledge: Adapted from previous studies; 6 items | Significant increase in INT compared to COM in at post-test (d = 1.63) but not maintained at follow-up (d = 0.76) | ||||||||||||

| 2. Attitudes | Adapted from previous studies; 3 items | Significant increase in INT compared to COM in 1 of the 3 items at post-test (d = 0.93) and follow-up (d = 0.24) | |||||||||||

| 3. Likelihood to intervene | Likelihood to question about suicide intent: Adapted from previous studies; 4 items | Significant increase in INT compared to COM at post-test (d = 1.51) and follow-up (d = 1.26) | |||||||||||

| Likelihood to intervene: Adapted from previous studies; 7 items | Significant increase in INT compared to COM at post-test (d = 0.47) and follow-up (d = 0.33) | ||||||||||||

| 4. Self-efficacy | Adapted from previous studies; 3 items | Significant increase in INT compared to COM at post-test (d = 0.75) and follow-up (d = 0.51) | |||||||||||

| Wyman et al. [29] | United States | INT = 166 CON = 176 | School staff | 44.5 (range = 22–75) | 18.1% | QPR | Gatekeeper training | Waitlist control | 1.5 h; NA | 1 year; 22.6% | 1. Knowledge | QPR knowledge: Self-developed items; 14 items | Significant intervention effect at follow-up (d = 0.44) |

| Self-evaluation knowledge: Self-developed items; 9 items | Significant intervention effect at follow-up (d = 0.74) | ||||||||||||

| 2. Self-efficacy | Self-developed items; 7 items | Significant intervention effect at follow-up (d = 0.95) | |||||||||||

| 3. Gatekeeper behavior | Asking students about suicide: Self-developed items; 1 item | No intervention effect at follow-up (d = 0.11); significant intervention by baseline interaction effect at follow-up | |||||||||||

| Referral behaviors: Self-developed items; 6 items | No intervention effect at follow-up (d = 0.09) | ||||||||||||

| Controlled trials without a pre-test | |||||||||||||

| Angerstein et al. [49] | North Texas, United States | INT = 53 COM1 = 26 COM2 = 46 | Counselors (N = 79) and building administrators (N = 71) | NR | NR | Project SOAR | Gatekeeper training | No intervention | 18 h; 12.8% | NA | 1. Knowledge | Suicide awareness Survey; Self-developed items; 10 items | Significant higher score in INT compared to COM1 at post-test (d = 2.04); significant higher score in INT compared to COM2 at post-test (d = 1.12) |

| 2. Attitudes | Suicide awareness Survey; Self-developed items; 5 items | Significant higher score in INT compared to COM1 at post-test (d = 0.83); no significant difference between INT and COM2 at post-test (d = 0.32) | |||||||||||

| Reis and Cornell [41] | Virginia, United States | INT = 238 CON = 172 | Counselors (N = 147) and teachers (N = 263) | NR | NR | QPR | Gatekeeper training | No intervention | 1–3 h; NA | 4.7 months (range from 1–22 months) | 1. Knowledge | The Student Suicide Prevention Survey; Self-developed items; 7 items | Significant intervention effect at follow-up (d = 0.20) |

| 2. Gatekeeper behavior | The Student Suicide Prevention Survey; Self-developed items; 3 items | INT made more contract with students (d = 0.44), but made fewer referrals for mental health services (d = 0.37) and questioned fewer potentially suicidal students (d = 0.36) than did COM | |||||||||||

| Before- and after comparison | |||||||||||||

| Angerstein et al. [49] | North Texas, United States | 62 | Counselors | NR | NR | Project SOAR | Gatekeeper training | NA | 8 h; 28% | NA | 1. Knowledge | Adapted from previous study [56]; 16 items | Significant increase in knowledge at post-test for high school of both groups (d for group A = 1.75; d for group B = 0.84) and for middle school of group B (d = 1.48) but not for group A (d = 0.24) |

| Mackesy-Amiti et al. [46] | United States | 205 | School personnel and community representatives | NR | 28.3% | Preparing for Crisis | Gatekeeper training | NA | 4 h; NR | NA | 1. Knowledge | PFC Knowledge test; Self-developed items; 25 items | Significant increase in knowledge at post-test (d = 0.79) |

| Robinson et al. [47] | Australia | 213 | School welfare staff | 42.5 (SD = 10.6) | 14.1% | Gatekeeper training | NA | 1 or 2 days; 13.2% | 6 months; 20.1% | 1. Knowledge | Knowledge of Deliberate Self-harm Questionnaire [57]; 10 items | Significant increase in knowledge at post-test (d = 0.56). 26% of participants who rated at high level at post-test demonstrated a reduction in knowledge; while 70% of those who had moderate level at post-test demonstrated increase in knowledge at follow-up | |

| 2. Attitudes | Attitudes towards Children who Self-Harm Questionnaire; [57]; 17 items | No significant change was observed at post-test (d = − 0.05) and follow-up (d = 0.08) | |||||||||||

| 3. Gatekeeper skills | (1) Skills in dealing with mental illness: Self-developed item; 1 item (2) Skills in dealing with self-harm: Self-developed item; 1 item |

Significant increase in perceived skills at post-test (d = 0.78) and maintained at follow-up (d = − 0.66) Significant increase in perceived skills at post-test (d = 1.40) and maintained at follow-up (d = − 0.20) |

|||||||||||

| 4. Self-efficacy | (1) Confidence in dealing with mental illness: Self-developed item; 1 item (2) Confidence in dealing with self-harm: Self-developed item; 1 item |

Significant increase in confidence at post-test (d = 0.58) and maintained at follow-up (d = − 0.14) Significant increase in confidence at post-test (d = 1.12) and maintained at follow-up (d = − 0.09) |

|||||||||||

| Suldo et al. [43] | United States | 121 | School Psychologists | 41.1 (SD = 10.8) | 18.3% | Gatekeeper | NA | 4 h; 53% | 9 months; 66.1% | 1. Knowledge | Knowledge on prevention, intervention, postvention, and overall knowledge score: Adapted from previous study [58]; 15 items | Significant time effect in all 4 scores at post-test (d = 0.45, 0.37, 0.75 and 0.80, respectively). Significant decrease in knowledge on prevention (d = − 0.69), postvention (d = − 0.52), and overall knowledge score (d = − 0.46) from post-test to follow-up. Score on intervention maintained from post-test to follow-up (d = 0.15) | |

| 2. Self-efficacy | Perceived competence in suicide-related professional activities of prevention, assessment, referral, counselling and postvention: Adapted from previous study [58]; 5 items | Significant increase in confidence to execute all 5 suicide-related professional activities at post-test (d = 0.72, 0.62, 0.60, 0.30, and 0.61, respectively), the effect was maintained in all of the activities at follow-up (d = − 0.36, − 0.03, − 0.04, − 0.02 and − 0.17, respectively) | |||||||||||

| Confidence in working with diverse youth, in terms of culture, English language speaking, disability, sexual orientation and strong religious affiliation) around suicide issues: self-developed items: 5 items | Significant increase in all 5 populations at post-test (d = 0.58, 0.70, 0.59, 0.64 and 0.51); the effect was maintained among the first four types of diverse youths (d = 0, − 0.07, − 0.16, 0.12, respectively), and further increase in youth with strong religious affiliations (d = 0.22) at follow-up | ||||||||||||

| Walsh et al. [22] | United States | 220 | School personnel | NR | 23% | Gatekeeper training | NA | 1.5 h; 18.1% | NA | 1. Likelihood to intervene | Adapted from previous studies [59, 60]; 1 item | Significant increase in likelihood to intervene at post-test (d = 0.69) | |

| 2. Self-efficacy | Confidence: Adapted from previous studies [59, 60]; 1 item | Significant increase in confidence at post-test (d = 0.59) | |||||||||||

| Comfort in asking: Adapted from previous studies [59, 60]; 1 item | Significant increase comfort in asking at post-test (d = 0.68) | ||||||||||||

| Johnson et al. [42] | Midwest, United States | 36 | High school and middle school staff | NA | NA | QPR suicide prevention program | in-person QPR Gatekeeper training + online conference work group | NA | three 90 min sessions; 100% | Monthly email for a 3 month time period following training; 100% | 1. Knowledge | QPR Knowledge: self-developed survey; 9 items | Significant increases in means of all knowledge items at post-test (d ranged from 1.11 to 1.90) |

| Lamis et al. [44] | Atlanta, Georgia, United States | 700 | School teachers (N = 620); school administrators (N = 35); classroom aids (N = 26); guidance counselors (N = 19) | 40.24 (SD = 12.03) | 20.4 | Act on FACTS: Making Educators Partners in Youth Suicide Prevention (MEP) | Online gatekeeper training | NA | 2 h; 100% | NA | 1. Knowledge | Suicide knowledge: self-developed items; 15 items | Significant increase in knowledge at post-test (d = 1.51) |

| 2. Self-efficacy | Self-developed items; 7 items | Significant increase in self-efficacy at post-test (d = 1.66) | |||||||||||

| Santos et al. [45] | Coimbra, Portugal | 66 | School primary healthcare professionals | 41.5 (MIN = 26, MAX = 61) | 7.6 | “+ Contigo” training | Gatekeeper training | NA | three 21 h courses; 100% | NA | 1. Knowledge | Knowledge about suicide prevention: Adapted from Suicide Behavior Attitude Questionnaire [61]; 13 items | Significant increase in knowledge at post-testa |

| 2. Attitudes | Adapted from Suicide Behavior Attitude Questionnaire [61]a: 1) negative feelings towards individuals with suicidal behaviors; item no. NA 2) attitudes towards the right to suicide; item no. NA |

No significant differences in attitudes toward individuals with suicidal behaviors or towards the right to suicide at post-testa | |||||||||||

| 3. Gatekeeper skills | Perceived professional skills: Adapted from Suicide Behavior Attitude Questionnaire [61]; item no. NA | Significant increase in perceived skills at post-testa | |||||||||||

| Groschwitz et al. [48] | Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany | 236 | school psychologists (N = 22), school social workers (N = 143), teachers (N = 55) and other school staff (N = 15) | NA | 16.9 | Strong Schools against Suicidality and Self-Injury (4S) program | Workshops | NA | 2 days; 99.6% | 6 months; 20.8% | 1. Knowledge | Adapted from Mental Health First Aid Training [62] and the Teacher Knowledge and Attitudes About Self-Injuries Questionnaire [63]; 8 items | Significant increase in perceived knowledge at post-test (d = 1.67) and maintained at follow-up (d = 1.41) |

| 2. Self-efficacy | Confidence in Gatekeeper skills: Adapted from Mental Health First Aid Training [62] and the Teacher Knowledge and Attitudes About Self-Injuries Questionnaire [63]; 8 items | Significant increase in confidence at post-test (d = 1.68) and maintained at follow-up (d = 1.56) | |||||||||||

| 3. Attitudes | Adapted from Attitudes towards Children Who Self-harm Questionaire [57]; 7 items | No significant differences in attitudes toward suicidality at post-test (d = 0.44) or at follow-up (d = 0.23) | |||||||||||

NA relevant information was not available

aThe effect size was not presented due to the necessary information not available

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Fifteen programmes were described in the 14 included studies. Approximately 3050 gatekeeper participants were covered in these programmes, only one of which solely involved female participants [40]. Participants included teachers, counsellors, social workers, and psychologists. Nine studies were conducted in the United States.

In terms of intervention, five out of the ten included studies used the QPR approach. Certified trainers led a single-session training which commonly lasted for 1–3 h [13, 21, 29, 41], whereas one study performed three 90 min sessions [42]. Three of these studies reinforced the intervention following the standard QPR programme. Wyman et al. [29] conducted a 30 min QPR refresher after several months. Cross et al. [13] provided an additional 25 min role play practice right after the QPR training to the intervention group. Johnson et al. [42] further created an online conference work group. Five other studies performed diverse interactive trainings [22, 40, 43–45]. Mackesy-Amiti et al. [46] conducted a 4 h postvention programme which prepared participants for developing and implementing a crisis plan for sudden loss as a way for suicide prevention. Two other 2 day programmes [47, 48] focused on the management of self-harm, a high risk factor of suicide. Angerstein et al. [49] formally evaluated a comprehensive school-based suicide programme, the Project SOAR, among two different samples.

In terms of study design, six studies had a follow-up evaluation and the duration of follow-up ranged from 3 to 22 months. A comparison group was used in six studies, though only two studies employed a random assignment of participants [13, 29], and only one study employed intent-to-treat analyses [29]. None of the included studies concealed allocation, or kept deliverers blind during the interventions (Table 2). Four studies compared the effect of gatekeeper training with a control group which received no intervention or waitlist intervention [21, 29, 41, 49]. One study compared the efficacy of QPR plus behavioural activation over QPR [13] and another study compared the efficacy of gatekeeper training delivered in a group format over a problem-oriented format [40]. In terms of measures, half of the studies reported a wide variation in the reliability of measure items across studies and constructs.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of the controlled trials included in the systematic review (N = 6)

Effectiveness of school-based gatekeeper training for adolescent suicide prevention

Knowledge

Thirteen studies assessed the outcome of gatekeepers’ knowledge; all of which showed benefits in increasing knowledge. Seven of these studies employed or adapted measure items from previous studies [13, 21, 43, 45, 47–49]. Of the four studies with a pretest–posttest-control (PPC) design, both of the two trials which compared QPR with a blank control reported significant training condition effects on improving declarative knowledge and self-perceived general knowledge [21, 29]. The other two trials testing different types of gatekeeper training yielded mixed results; the superiority of an additional rehearsal to standard QPR was not found [13], while the gatekeeper training in a problem-oriented format was significantly better than a group-oriented format in increasing the knowledge about prevention, but not the general knowledge or knowledge in identification of warning signs [40]. Despite significant increases in knowledge at immediate post-test found for all gatekeeper training conditions in these four studies, one study further showed that such a positive effect was not maintained at a 3 month follow-up [21]. Both of the studies with a posttest only with control (POC) design compared the gatekeeper raining with a null control and found significant higher scores on factual knowledge about suicide in the intervention group [41, 49].

All the eight studies with a single-group pre-post-test (SGPP) design detected a significant increase in specific knowledge outcomes immediately after the gatekeeper trainings, including knowledge about suicide prevention [42, 44, 45, 49]. suicidality-related self-injury [47, 48], crisis preparing for suicide postvention [46], and comprehensive suicide-related practices [43]. However, findings on the long-term effects of gatekeeper trainings were inconsistent. Groschwitz et al. [48] observed the maintenance of the significant gain in knowledge about suicidality and self-injury at the 6 month follow-up. Robinsons et al. [47] reported a reduction in knowledge at the 6 month follow-up among participants rated at the high knowledge level at post-test, whilst a steady increase among those at the moderate level. Suldo et al. [43] found that only score on knowledge about intervention was maintained at 9 month follow-up, whereas scores on that about prevention, postvention and total knowledge decreased significantly from post-test to follow-up.

Moderators were also identified for the above gatekeeper training effects. Individuals with a lower knowledge level prior to the trainings evidenced greater gains [21, 29, 47]. Tompkins et al. [21] showed a significant improvement in QPR knowledge among teachers and administrators but not support staff. Angerstein et al. [49] detected a notable knowledge increase in those trained at both target high schools but at only one of the two middle schools.

Gatekeeper skills

Three studies assessed the outcome of gatekeeper skills and all of them showed significant positive effect. Cross et al. [13] showed that participants in the QPR plus behavioral rehearsal condition demonstrated significantly higher total gatekeeper skills than those in the QPR condition, but the 3 month follow-up scores significantly decreased. Specifically, the effect was found on general communication but not on suicide-related skills. Robinson et al. [47] reported a positive change in the skills of dealing with self-harm at post-test, which was maintained at the 6 month follow-up. The most improvement occurred among those who reported low and moderate level of skills prior to the course. Finally, Santos et al. [45] also found a significantly higher level of perceived professional skills right after the gatekeeper training.

Attitude towards adolescent suicide

Five studies measured the change in attitude towards adolescent suicide. A positive effect of gatekeeper trainings was observed in two controlled trials; one found a higher score on attitudes about suicide in the training group compared to one of the control groups [49]; while the other observed a significant increase only in one (“suicide is preventable”) of the three attitudes items at post-test and 3 month follow-up [21]. None of the three studies with a SGPP design showed a significant time effect of gatekeeper trainings on the attitudes towards suicidal (or related) behaviors and suicide prevention [45, 47, 48]. The last four studies employed or adapted the items from previous studies.

Self-efficacy

All nine studies that assessed change in self-efficacy reported positive effects. Five had adapted scales from previous studies [13, 21, 22, 48]. The four studies with a PPC design reported a significant increase in self-efficacy for identifying and responding to suicidal individuals after training and/or at a long-term follow-up. The intervention was also found to be more effective than the blank control group [21, 29]. However, comparison between different types of gatekeeper training indicated no significant condition effect [13, 40].

The five studies with a SGPP design documented a significant increase in trainees’ confidence in dealing with suicidality immediately at post-training. Long-term effects were inconsistent in three studies that assessed them. Two showed that gains in self-efficacy were maintained at 6 month follow-up [47, 48]. The third, Suldo et al. [43] reported a steady increase from post-test to 9 month follow-up in participants’ confidence in their abilities to execute the suicide-related professional activities; and in the confidence of working with youth with strong religious affiliations but not with those from diverse cultures, with disabilities, with diverse sexual orientations or those who were English language learners.

Participants’ profession roles and professional experience were identified as potential moderators of the gatekeeper training effects. Lamis et al. [44] revealed a significantly larger increase in self-efficacy at post-test among teachers and classroom aids than among guidance counsellors and school administrators. Groschwitz et al. also found teachers improved in confidence most, followed by school social workers and school psychologists [48]. Several studies consistently showed that participants with less knowledge and experience around suicide issues prior to the trainings demonstrated greater gains in self-efficacy [21, 47, 48].

Likelihood to intervene

Two studies adapted items from previous research to evaluate the outcome of self-reported likelihood to intervene; both revealed a positive effect. Tompkins et al. [21] reported a significant increase in the likelihood to question a student about suicide intent, as well as the likelihood to intervene in the intervention group compared to the null-control group at post-test and 3 month follow-up. Individuals with prior suicide prevention training evidenced more pre-post changes in the likelihood to question suicide intent. Walsh et al. [22] also detected an increase in the likelihood to directly question a young person about suicide intent from pre-test to post-test.

Gatekeeper behaviour

Three controlled trials evaluated the effects on gatekeeper behaviour with self-developed items, and two of them found positive effects on specific behaviours. Wyman et al. [29] found that the gatekeeper training effect on asking students about suicide only presented itself at the 1 year follow-up among staff with such experience at baseline, and no overall effect for suicide identification behaviour was illustrated. Reis and Cornell [41] found that the QPR training group made more contract with students, but unexpectedly, questioned fewer potentially suicidal students and referred fewer students to mental health services than did the null-control group at the 4.7 month follow-up. Cross et al. [13] further showed that an additional behavioural rehearsal to the standard QPR did not significantly increase the number of referrals at the 3 month follow-up.

Discussion

Given the adverse impact of suicide, there is an urgent need to identify ways to effectively reduce suicide among adolescents. In response to this significant health concern, there has been a surge of programmes using the gatekeeper approach for reducing adolescent suicide. The present study conducted a systematic review of the effectiveness of school-based gatekeeper training for adolescent suicide prevention on gatekeepers’ self-reported knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours relating to the detection of and responses to suicidality. It is important to point out that direct comparisons between studies included in the systematic review are difficult due to the tremendous heterogeneity in sample characteristics, the nature of the comparison groups, mode of intervention, intensity and duration of intervention, outcome measures and length of follow-ups. Nevertheless, findings from the systematic review provide some evidence that gatekeeper training programme for adolescent suicide prevention are generally effective in improving participants’ knowledge and skills, while mixed evidence exist with regards to changing participants’ attitudes and gatekeeper behaviour.

Results from the systematic review show that most of the studies evaluated the effectiveness of the training in improving knowledge as well as self-efficacy, and there is established evidence to support such improvements. Such positive effects were maintained at follow-up. There is also evidence that school-based gatekeeper training is effective in improving participants’ skills and likelihood to intervene, although the number of studies measuring these outcomes are relatively small. Since most of the gatekeeper programmes aim at addressing signs of suicide and improving participants’ skills in intervening with at-risk individuals, it is conceivable that they can be effective in improving participants’ knowledge, self-efficacy and skills. It is further reported that the effect of gatekeeper training is comparable with those with an additional behavioural rehearsal component [13], suggesting that school-based gatekeeper training can potentially be a useful approach in preventing adolescent suicide.

Contrary to our expectation, mixed evidence exists as to the effectiveness of gatekeeper training in changing participants’ attitudes. Results are surprising given that one of the key focuses of gatekeeper training programme is to improve participants’ attitudes. It is, however, important to note that in one study a ceiling effect was seen in half of the items at baseline. This indicated that only limited improvement could be shown on the measures being used [47]. It might therefore be plausible that most of the participants have already shown positive attitudes towards adolescent suicide before receiving gatekeeper training. The heterogeneity in operationalization and measures used for attitudes in various studies might also explain the mixed results. More studies are warranted to investigate the effect of school-based gatekeeper training in improving participants’ attitudes towards adolescent suicide.

Only three of the included studies measured changes in gatekeeper behaviour, and the mixed results found imply that changes in knowledge and skills in suicide prevention may not translate directly to behavioural change. As most of the studies have a relatively short follow-up time, it may not be long enough to capture the change of behaviour among the participants. Unexpectedly, one study found that gatekeeper training resulted in participants in the intervention group questioning and referring a lower number of at-risk students to mental health services. The authors speculated that the gatekeeper training might have improved participants’ confidence and knowledge in adolescent suicide prevention, as well as their ability in assessing students’ abnormal behaviour without the need to ask questions [41]. Establishing contact with at-risk students is the very first step in suicide intervention. It is therefore imperative to examine how the change in knowledge and skills can be translated into change in gatekeeper behaviour so that adolescents who are at risk of suicide could be approached and intervened effectively. Inconsistency in the effectiveness on ultimate gatekeeper behaviour and its correlates could also be explained by a study reporting negative help seeking attitudes among student suicide attempters [29]. The study strongly recommended an integration of the gatekeeper program with interventions on students’ help-seeking behaviour, to help facilitate an open communication [29].

It is important to note that the quality of the studies may have a huge effect on the conclusions that can be drawn. The present review found many of the studies to be of low methodological quality. While the use of RCT is regarded as the best design in delineating cause-and-effect relationships and minimizing confounding variables, the majority of the controlled studies did not use proper randomization and none used allocation concealment when assigning participants. The use of pre- and post- intervention comparisons or non-equivalent control groups was prevalent. No studies kept programme deliverers blinded during the research. Only one study used intent-to-treat analysis to take into account the participants who were lost to follow up. A huge variation was also found on the measures used, with a majority of them reporting the use of self-developed measures. In addition, there is a dearth of studies measuring the effectiveness of school-based gatekeeper programmes in decreasing rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, or deaths by suicide. There is an urgent need to design a high-quality gatekeeper training programme evaluated with psychometrically sound outcome measures.

In addition to the efficacy of gatekeeper approaches, the practical implementation of a specific training program may also greatly affect its effectiveness across different contexts in terms of notable improvements in the target cognitions and behaviours [50]. The assessment of implementation outcomes using high-quality instruments is critical to identifying the most optimal implementation strategies [51] However, only one of the included studies quantitatively measured the acceptability and feasibility of the proposed program [22]. Moreover, developing standardised evaluation methods for implementation science would contribute to the appraisal and comparison of diverse gatekeeper training programs [51].

Limitations

There are several limitations that should be noted. First, the present review was restricted to English articles; there is a possibility that some articles in other languages may have been overlooked in the review. Second, the literature search was conducted in only four databases. Nevertheless, the databases included were deemed the most relevant ones to adolescent suicide and articles that did not explicitly mention gatekeeper training in their title or abstracts were retained in the first screening, and their full-texts were reviewed before a decision was made. Third, although a positive finding on most outcomes was observed, no conclusion could be made as to the extent of the benefits which were due to social or group effect. Fourth, this study reviews the evidence on changes in gatekeepers’ self-reported cognitive outcomes and behaviour as proxy indicators of reduction in suicide-risk. Few included studies have attempted to relate these changes to those in rates of successful or attempted suicide despite a large number of individual adolescents whose gatekeepers will have received the forms of training and support we have reviewed here. Fifth, the present review did not specifically examine the components which may make the programme effective. Sixth, publication bias might exist in the review, as the present study did not systematically search for articles in the grey literature. Future studies should seek to include other indicators of the effectiveness of school-based gatekeeper training and to conduct a wider review with studies not formally published in the research literature. Lastly, qualitative synthesis of results is inherent to the nature of a systematic review. However, effect size was calculated and presented for each study. Meta-analysis would not be possible on the literature identified for this topic due to the great heterogeneity observed in the study characteristics and limited data on specific outcome measures (e.g. gatekeeper skills).

Conclusion

The present study conducted a systematic review on the effectiveness of school-based gatekeeper training for adolescent suicide prevention. Findings suggest that school-based gatekeeper training is effective in improving participants’ knowledge, skills, self-efficacy and likelihood to intervene, while mixed evidence exists in changing participants’ attitudes and gatekeeper behaviour. Methodological issues, such as lack of RCT and the inability to use validated measures, jeopardize the conclusions that can be drawn from the studies. More high-quality studies with longer follow-up periods are warranted to ascertain the effect of school-based gatekeeper training in improving participants’ knowledge, skills, attitudes towards adolescent suicide and gatekeeper behaviour. Such studies should also seek to include long term outcomes such as suicide attempts or behaviour.

Relevance for clinical practice

Findings of the present study have important implications for the design of adolescent suicide prevention programmes. Findings suggest that a school-based gatekeeper approach, training teachers or school staff to identify and intervene on behalf of at-risk students, could be implemented in programmes aimed at adolescent suicide prevention. Teachers and school staff can play an important role and school potentially serves as a useful setting in which such programmes could be implemented. Mental health professionals should collaborate with schools in the design and implementation of further research to adequately evaluate and establish the benefits of such adolescent suicide prevention approaches.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

PKHM and TTK designed the study. TTK and MQX did the literature search. PKHM, MQX and TTK did the screening. PKHM and TTK drafted the manuscript. PKHM and MQX revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Phoenix K. H. Mo, Phone: +852 22528765, Email: phoenix.mo@cuhk.edu.hk

Ting Ting Ko, Email: tintin6333@gmail.com.

Mei Qi Xin, Email: meiqixin@link.cuhk.edu.hk.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Surveillance of suicide and suicide attempts 2017. http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/en/. Accessed 1 Mar 2017.

- 2.Wasserman D, Cheng QI, Jiang G-X. Global suicide rates among young people aged 15–19. World Psychiatry. 2005;4(2):114–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohler B, Earls F. Trends in adolescent suicide: misclassification bias? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):150–153. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.1.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westefeld JS, Button C, Haley JT, Jr, Kettmann JJ, Macconnell J, Sandil R, et al. College student suicide: a call to action. Death Studies. 2006;30(10):931–956. doi: 10.1080/07481180600887130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weitzman ER. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. J Nerv Ment Disord. 2004;192(4):269–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vajani M, Annest JL, Crosby AE, Alexander JD, Millet LM. Nonfatal and fatal self-harm injuries among children aged 10–14 years—United States and Oregon, 2001–2003. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(5):493–506. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moskos M, Olson L, Halbern S, Keller T, Gray D. Utah youth suicide study: psychological autopsy. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35(5):536–546. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing suicide: a national imperative. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y-Y, Tsai P-C, Chen P-H, Fan C-C, Hung GC-L, Cheng AT. Effect of media reporting of the suicide of a singer in Taiwan: the case of Ivy Li. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(3):363–369. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns JM, Patton GC. Preventive interventions for youth suicide: a risk factor-based approach. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(3):388–407. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlton PA, Deane FP. Impact of attitudes and suicidal ideation on adolescents’ intentions to seek professional psychological help. J Adolesc. 2000;23(1):35–45. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart SE, Manion IG, Davidson S, Cloutier P. Suicidal children and adolescents with first emergency room presentations: predictors of six-month outcome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(5):580–587. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200105000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cross WF, Seaburn D, Gibbs D, Schmeelk-Cone K, White AM, Caine ED. Does practice make perfect? A randomized control trial of behavioral rehearsal on suicide prevention gatekeeper skills. J Primary Prevent. 2011;32(3–4):195–211. doi: 10.1007/s10935-011-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller DN, Eckert TL, Mazza JJ. Suicide prevention programs in the schools: a review and public health perspective. Sch Psychol Rev. 2009;38(2):168. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention US. Suicide prevention: youth suicide 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/youth_suicide.html. Accessed 1 Mar 2017.

- 16.Kalafat J, Elias M. An evaluation of a school-based suicide awareness intervention. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994;24(3):224–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz C, Bolton SL, Katz LY, Isaak C, Tilston-Jones T, Sareen J. A systematic review of school-based suicide prevention programs. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(10):1030–1045. doi: 10.1002/da.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting DM, Shaffer D. Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(4):386–405. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046821.95464.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office of the Surgeon General, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: goals and objectives for action: a report of the US Surgeon General and of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012. [PubMed]

- 21.Tompkins TL, Witt J, Abraibesh N. Does a gatekeeper suicide prevention program work in a school setting? Evaluating training outcome and moderators of effectiveness. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(5):506–515. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.5.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh E, Hooven C, Kronick B. School-wide staff and faculty training in suicide risk awareness: successes and challenges. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;26(1):53–61. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.QPR Institute. What is QPR 2015. https://www.qprinstitute.com/about-qpr. Accessed 1 Mar 2017.

- 24.Living Works Education. Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST) 2014. https://www.livingworks.net/programs/asist/. Accessed 1 Mar 2017.

- 25.Brown CH, Wyman PA, Guo J, Peña J. Dynamic wait-listed designs for randomized trials: new designs for prevention of youth suicide. Clin Trials. 2006;3(3):259–271. doi: 10.1191/1740774506cn152oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staal MA. The assessment and prevention of suicide for the 21st century: the Air Force’s community awareness training model. Mil Med. 2001;166(3):195. doi: 10.1093/milmed/166.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King KA, Price JH, Telljohann SK, Wahl J. High school health teachers’ perceived self-efficacy in identifying students at risk for suicide. J Sch Health. 1999;69(5):202–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1999.tb06386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joffe P. An empirically supported program to prevent suicide in a college student population. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(1):87–103. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyman PA, Brown CH, Inman J, Cross W, Schmeelk-Cone K, Guo J, et al. Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(1):104. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden DC, Lauer P. Prevalence of suicide programs in schools and roadblocks to implementation. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000;30(3):239–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yip P, Law Y. Towards evidence-based suicide prevention programmes. Crisis. 2010;32:117–120. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isaac M, Elias B, Katz LY, Belik SL, Deane FP, Enns MW, et al. Gatekeeper training as a preventative intervention for suicide: a systematic review. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(4):260–268. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunnell D, Frankel S. Prevention of suicide: aspirations and evidence. BMJ Br Med J. 1994;308(6938):1227. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6938.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson G, Winstanley J, Bertapelle T. Suicide prevention training after traumatic brain injury: evaluation of a staff training workshop. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003;18(5):445–456. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kataoka S, Stein BD, Nadeem E, Wong M. Who gets care? Mental health service use following a school-based suicide prevention program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1341–1348. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31813761fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associate; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Stat. 1981;6(2):107–128. doi: 10.3102/10769986006002107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris SB. Estimating effect sizes from pretest–posttest-control group designs. Organ Res Methods. 2008;11(2):364–386. doi: 10.1177/1094428106291059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Essentials of behavioral research: methods and data analysis (3rd edition) Boston, NA: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klingman A. Action research notes on developing school staff suicide-awareness training. Sch Psychol Int. 1990;11(2):133–142. doi: 10.1177/0143034390112007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reis C, Cornell D. An evaluation of suicide gatekeeper training for school counselors and teachers. Prof Sch Couns. 2008;11(6):386–394. doi: 10.5330/PSC.n.2010-11.386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson LA, Parsons ME. Adolescent suicide prevention in a school setting: use of a gatekeeper program. NASN Sch Nurs. 2012;27(6):312–317. doi: 10.1177/1942602X12454459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suldo S, Loker T, Friedrich A, Sundman A, Cunningham J, Saari B, et al. Improving school psychologists’ knowledge and confidence pertinent to suicide prevention through professional development. J Appl Sch Psychol. 2010;26(3):177–197. doi: 10.1080/15377903.2010.495919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamis DA, Underwood M, D’Amore N. Outcomes of a suicide prevention gatekeeper training program among school personnel. Crisis. 2017;38(2):89–99. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santos JC, Simoes RM, Erse MP, Facanha JD, Marques LA. Impact of “+ Contigo” training on the knowledge and attitudes of health care professionals about suicide. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2014;22(4):679–684. doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.3503.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackesy-Amiti ME, Fendrich M, Libby S, Goldenberg D, Grossman J. Assessment of knowledge gains in proactive training for postvention. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996;26(2):161–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson J, Gook S, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Yung AR. Managing deliberate self-harm in young people: an evaluation of a training program developed for school welfare staff using a longitudinal research design. BMC psychiatry. 2008;8(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Groschwitz R, Munz L, Straub J, Bohnacker I, Plener PL. Strong schools against suicidality and self-injury: evaluation of a workshop for school staff. Sch Psychol Q. 2017;32(2):188–198. doi: 10.1037/spq0000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angerstein G, Linfield-Spindler S, Payne L. Evaluation of an urban school adolescent suicide program. Sch Psychol Int. 1991;12(1–2):25–48. doi: 10.1177/0143034391121004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–1267. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0342-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cross W, Matthieu MM, Cerel J, Knox KL. Proximate outcomes of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in the workplace. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(6):659–670. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyman PA, Brown CH, Inman J, Cross W, Schmeelk-Cone K, Guo J, et al. Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(1):104–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cross W, Matthieu MM, Lezine D, Knox KL. Does a brief suicide prevention gatekeeper training program enhance observed skills? Crisis. 2010;31(3):149–159. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matthieu MM, Cross W, Batres AR, Flora CM, Knox KL. Evaluation of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in veterans. Arch Suicide Res. 2008;12(2):148–154. doi: 10.1080/13811110701857491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shneidman ES, Farberow NL, Leonard CV. Some facts about suicide. Washington: United States Government Printing Office; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crawford T, Geraghty W, Street K, Simonoff E. Staff knowledge and attitudes towards deliberate self-harm in adolescents. J Adolesc. 2003;26(5):623–633. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(03)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Debski J, Spadafore CD, Jacob S, Poole DA, Hixson MD. Suicide intervention: training, roles, and knowledge of school psychologists. Psychol Sch. 2007;44(2):157–170. doi: 10.1002/pits.20213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eggert L, Karovsky PP, Pike K. Washington State Youth Suicide Prevention Program: Pathways to enhancing community capacity in preventing youth suicidal behaviors. Olympia, WA: State Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Randell BP. CAST-Plus: a suicide prevention communit partnership. Grant funded by the Centers for Disease Control; 2002. Contract No.: CCR021466-01.

- 61.Botega NJ, Reginato DG, da Silva SV, da Silva Cais CF, Rapeli CB, Mauro MLF, et al. Nursing personnel attitudes towards suicide: the development of a measure scale. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27(4):315–318. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462005000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kitchener BA, Jorm AF. Mental health first aid training for the public: evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry. 2002;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heath NL, Toste JR, Beettam EL. “I am not well-equipped”: high school teachers’ perceptions of self-injury. Can J Sch Psychol. 2006;21(1–2):73–92. doi: 10.1177/0829573506298471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.