Short abstract

Introduction

We aimed to develop and validate a prognostic score for disability at discharge and functional outcome at three months in patients with acute ischemic stroke based on clinical information available on admission.

Patients and methods

The Dutch Stroke Score (DSS) was developed in 1227 patients with ischemic stroke included in the Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) In Stroke study. Predictors for Barthel Index (BI) at discharge (‘DSS-discharge’) and modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at three months (‘DSS-3 months’) were identified in multivariable ordinal regression. The models were internally validated with bootstrapping techniques. The DSS-3 months was externally validated in the PRomoting ACute Thrombolysis in Ischemic StrokE study (1589 patients) and the Preventive Antibiotics in Stroke Study (2107 patients). Model performance was assessed in terms of discrimination, expressed by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and calibration.

Results

At model development, the strongest predictors of Barthel Index at discharge were age per decade over 60 (odds ratio = 1.55, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.41–1.68), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (odds ratio = 1.24 per point, 95% CI 1.22–1.26) and diabetes (odds ratio = 1.62, 95% CI 1.32–1.91). The internally validated AUC was 0.76 (95% CI 0.75–0.79). The DSS-3 months, additionally consisting of previous stroke and atrial fibrillation, performed similarly at internal (AUC 0.75, 95% CI 0.74–0.77) and external validation (AUC 0.74 in PRomoting ACute Thrombolysis in Ischemic StrokE (95% CI 0.72–0.76) and 0.69 in Preventive Antibiotics in Stroke Study (95% CI 0.69–0.72)). Observed outcome was slightly better than predicted.

Discussion: The DSS had satisfactory performance in predicting BI at discharge and mRS at three months in ischemic stroke patients.

Conclusion

If further validated, the DSS may contribute to efficient stroke unit discharge planning alongside patients' contextual factors and therapeutic needs.

Keywords: Stroke, clinical prediction model, prognosis, hospital discharge, rehabilitation, discharge planning

Introduction

In 2015, over 26,000 patients were admitted to hospitals because of ischemic stroke in the Netherlands.1 Most of these patients need rehabilitation to achieve better recovery in the first months after stroke and reduce long-term disability. In the Netherlands, around 8% of all stroke patients is referred to an inpatient rehabilitation centre.2 Typically, these patients are too disabled to be discharged home, but they are cognitively and physically fit enough to participate in intensive therapy sessions and have sufficient social support to return home within two to four months. Alternatively, patients may be referred to skilled nursing and geriatric rehabilitation facilities. These patients are often elderly, suffer from comorbidities and have a poorer functional prognosis. Still, the majority of stroke patients (60%) is discharged home, mostly with community rehabilitation.2 Discharge planning may depend on multiple factors such as comorbidities and contextual factors (e.g. the presence of a healthy caregiver and premorbid level of functioning). The importance of the contextual factors increases as the functional prognosis of the stroke decreases. Therefore, early prediction of functional outcome may contribute to efficient discharge planning.

The most widely used functional outcome measure in acute stroke is the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). The mRS measures the degree of disability in daily activities. It is scored on an ordinal scale ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death).3 Another frequently used outcome measure in rehabilitation is the Barthel Index (BI), measuring performance in 10 basic activities of daily living (ADL).4 BI is associated with duration of hospital stay.5

Previous studies identified many prognostic factors for outcome (measured by BI or mRS) after acute stroke.6 Prognostic factors can be combined in a model to identify patients at risk for poor outcome.7 Although several prognostic models exist to predict outcome in stroke, very few are adequately validated for use in daily clinical practice.8 We aimed to develop and validate a prognostic score for disability (BI) at discharge and functional outcome (mRS) at three months after acute ischemic stroke based on clinical information available on admission.

Methods

Derivation cohort

Data from the Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) In Stroke (PAIS) study were used for model development.9 PAIS was a multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled phase III trial assessing the effect of high dose paracetamol on the functional outcome in patients with acute stroke. In short, patients were eligible for inclusion if they were diagnosed with acute ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage, had a prestroke mRS < 2 and study treatment could be started within 12 h after onset of symptoms. We used data of all patients with ischemic stroke included in PAIS.

Outcome measures

We used the BI at discharge as the outcome measure for short-term disability. The BI is an ordinal scale used to measure performance in ADL. The scale ranges from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating a greater likelihood of being able to carry out ADL independently.4 In PAIS, the BI was measured at 14 days after enrolment or at hospital discharge if this occurred earlier (70% of the patients stayed for ≥3 days).9 However, choice of the optimal rehabilitation route mostly depends on more than just discharge outcome.10 Therefore, we additionally evaluated functional outcome at three months with the mRS. The mRS is an ordinal scale used to measure the degree of disability in daily activities and ranges from 0 (no symptoms) to 6, with mRS 5 indicating severe disability and mRS 6 indicating death.3

Model development

To identify predictors of disability and functional outcome, we selected variables that were clinically relevant and/or previously reported to predict outcome after stroke in the literature.6 These variables were sex, age, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, diabetes, previous stroke, atrial fibrillation and hypertension. All predictors were entered into multivariable ordinal regression with backward selection with p < 0.2 for inclusion, separately for BI at discharge and mRS at three months. The final associations were presented as a set of odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to indicate the individual predictor effects. ORs from an ordinal logistic regression model can be interpreted as a common OR for shifting over the full outcome range.11

The resulting models, the Dutch Stroke Score (DSS) for BI at discharge (‘DSS-discharge’) and mRS at three months (‘DSS-3 months’), were internally validated using standard bootstrapping procedures to avoid an optimistic estimate of the model performance, which often occurs when model performance is only evaluated directly in the derivation cohort (apparent validation). In the bootstrap procedure, random samples are drawn from the original sample, each with the same number of patients as the original sample. In each of these samples the modeling steps are repeated and the resulting models are subsequently evaluated on the original sample. The mean model performance in all 500 bootstrap models represents the expected performance of the models in future, similar patients.12

Validation cohorts

For external validation, we used data from the PRomoting ACute Thrombolysis in Ischemic StrokE (PRACTISE) study and Preventive Antibiotics in Stroke Study (PASS). PRACTISE was a cluster-randomised trial designed to evaluate an implementation strategy to increase the proportion of patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis.13 PRACTISE registered adult patients with acute stroke admitted within 24 h after onset of symptoms and had no age restrictions. We used data from ischemic stroke patients admitted within 4 h as in these patients detailed clinical data were available.

PASS was a multicentre, randomised, open-label trial designed to assess whether or not preventive antimicrobial therapy with ceftriaxone improves functional outcome in patients with acute stroke.14 PASS included adult patients with clinical symptoms of a stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) admitted within 24 h after symptom onset. We used data of all patients with ischemic stroke included in PASS.

Model validation

The validity of the DSS-3 months was assessed in terms of discrimination and calibration. The external validation cohorts did not have data on BI at discharge. Discrimination refers to how well the model distinguishes between those who have good outcome (mRS 0–2) vs. those who have poor outcome (mRS 3–6) at three months. Discrimination was assessed by calculating the ordinal area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.15 The AUC ranges from 0.5 for non-informative models to 1.0 for perfect models.12 Calibration indicates the agreement between predicted and observed probabilities. Calibration was assessed graphically in a calibration graph, and expressed as the calibration slope and an intercept. The calibration slope is ideally equal to 1 and describes the effect of the predictors in the validation cohort versus in the derivation cohort. The intercept indicates whether predictions are systematically too high or too low, and should ideally be zero.12

At external validation, the discriminative power of a model may be influenced by differences in predictor effects, but also by differences in distribution of patient characteristics (case-mix) between the derivation and validation cohort.16 In a more homogeneous population, discrimination between patients with good vs. poor outcome is more difficult than in a heterogeneous population. To take this into account, we calculated the case-mix-corrected AUC. The case-mix-corrected AUC reflects the discriminative power of a model, assuming that the regression coefficients are correct for the validation population. It was calculated by simulating new outcome values for all patients in the validation dataset, based on the predicted risks for each patient.16

After external validation, we fitted the DSS-3 months on the combined data of all three trials to get the best estimates for the regression coefficients.17 The DSS-discharge and DSS-3 months were presented in a score chart, as a score plot simplified to five BI and mRS outcome classes (based on clinically relevant cutoffs), and as formulas to calculate the predicted outcomes.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.3.2 (R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria). The calibration plots were created with an updated version of the val.prob function (rms library in R). Missing values in the development and validation cohorts were statistically imputed using a multiple imputation method exploiting correlations between predictor variables and between predictor variables and the outcome variables (mice function in R). Complete case analyses were done for comparison with the imputed analyses.

Results

Study population

For model development, we included 1227 patients with ischemic stroke from the PAIS trial. Missing data on hypertension (3.1%) were statistically imputed; all other baseline variables and outcomes were complete. For the external validation of the model predicting mRS at three months, we included, 1657 ischemic stroke patients from the PRACTISE study. Sixty-eight patients with missing data on mRS at three months were excluded, resulting in an external validation sample of 1589 patients. Other missing data (0.6%) were statistically imputed. Additionally, we externally validated the model for functional outcome at three months in, 2125 ischemic stroke patients from the PASS study. Eighteen patients with missing data on the mRS at three months were excluded, resulting in an external validation sample of 2107 patients. Other missing data (0.4%) were statistically imputed.

In all three studies, most patients (55–58%) were male and the mean age was around 70 years (Table 1). The three populations are comparable concerning baseline characteristics, except for time from stroke onset to inclusion (PAIS and PRACTISE had a smaller time window compared to PASS), previous stroke (33% in PASS vs. 20% in the other trials) and diabetes (20% in PASS vs. 15–17% in PAIS and PRACTISE). The number of patients with poor outcome (mRS 3–6) was lower in PASS compared to PAIS and PRACTISE (online supplemental Figure 1(a)). In PAIS, this is reflected in the substantial proportion of patients with favorable outcome on the BI at discharge (online supplemental Figure 1(b)).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included patients from the PAIS, PRACTISE and PASS studies.

| PAIS (n = 1227) | PRACTISE (n = 1589) | PASS (n = 2107) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 675 (55%) | 872 (55%) | 1212 (58%) |

| Age in years (mean, sd) | 70.1 (13.4) | 70.6 (13.4) | 71.9 (12.5) |

| Time from onset to CT in hours (median, IQR) | 3.0 (1.8–5.9) | 2.0 (1.4–3.0) | NA |

| NIHSS (median, IQR) | 6.0 (3.0–11.0) | 5.0 (3.0–12.0) | 5.0 (3.0–9.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 181 (15%) | 266 (17%) | 423 (20%) |

| Previous ischemic stroke | 245 (20%) | 318 (20%) | 698 (33%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 190 (16%) | 290 (18%) | 326 (16%) |

| Hypertension | 601 (49%)a | 811 (51%) | 1154 (55%) |

| Current smoking | 380 (31%) | 374 (24%) | 524 (25%) |

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; IQR: interquartile range; NA: not available; PRACTISE: PRomoting ACute Thrombolysis in Ischemic StrokE; PASS: Preventive Antibiotics in Stroke Study; PAIS: Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) In Stroke.

a38 Missings.

Model development in PAIS

The relation between age as a continuous variable and the log odds of disability (BI) in the development data was non-linear and intensified when age was above 60 years (online supplemental Figure 2). Because of this non-linearity, we considered different age effects for patients older vs. younger than 60 years.

Of the variables considered, age per decade above 60, NIHSS per point and diabetes were the strongest predictors of BI at discharge, both in univariable (data not shown) and multivariable analysis (Table 2) and were included in the model for disability at discharge. The internally validated ordinal AUC was 0.76 (95%CI 0.75–0.79). Age per decade above 60, NIHSS per point, diabetes, previous stroke and atrial fibrillation were the strongest predictors of mRS at three months, both in univariable (data not shown) and multivariable analysis (Table 2) and were included in the final model for mRS at three months. The internally validated ordinal AUC was 0.75 (95%CI 0.74–0.77).

Table 2.

Associations of predictors in multivariable ordinal regression with lower BI at discharge in PAIS and higher mRS at three months in in PAIS, PRACTISE and PASS.

| PAIS (n = 1227) BI at discharge |

PAIS (n = 1227) mRS at three months |

PRACTISE (n = 1589)mRS at three months |

PASS (n = 2107)mRS at three months |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Male sex | 1.01 (0.79–1.23) | 0.923 | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.189 | 0.81 (0.67–0.97) | 0.022 | 0.77 (0.61–0.93) | 0.002 |

| Age per decadeif over 60a,b | 1.55 (1.41–1.68) | <0.001 | 1.86 (1.64–2.12) | <0.001 | 1.80 (1.61–2.01) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.41–1.70) | <0.001 |

| Age per decadeif under 60 | 1.07 (0.83–1.30) | 0.589 | 0.93 (0.76–1.15) | 0.514 | 0.89 (0.74–1.07) | 0.211 | 0.70 (0.56–0.86) | <0.001 |

| NIHSS per pointa,b | 1.24 (1.22–1.26) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.17–1.22) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.17–1.21) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.19–1.23) | <0.001 |

| Diabetesa | 1.62 (1.32–1.91) | 0.002 | 1.87 (1.40–2.51) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.34–2.17) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.11–1.51) | 0.007 |

| Previous strokeb | 1.18 (0.91–1.45) | 0.225 | 1.67 (1.29–2.16) | <0.001 | 1.59 (1.27–1.99) | <0.001 | 1.14 (0.98–1.31) | 0.111 |

| Atrial fibrillationb | 1.09 (0.78–1.39) | 0.592 | 1.41 (1.05–1.89) | 0.022 | 1.24 (0.98–1.57) | 0.076 | 1.14 (0.91–1.36) | 0.264 |

| Hypertension | 1.06 (0.84–1.28) | 0.594 | 1.02 (0.83–1.26) | 0.844 | 1.08 (0.90–1.30) | 0.384 | 0.91 (0.75–1.07) | 0.246 |

BI: Barthel Index; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PRACTISE: PRomoting ACute Thrombolysis in Ischemic StrokE; PASS: Preventive Antibiotics in Stroke Study; PAIS: Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) In Stroke.

aParameter included in final model on BI at discharge.

bParameter included in final model on mRS at three months.

External validation in PRACTISE and PASS

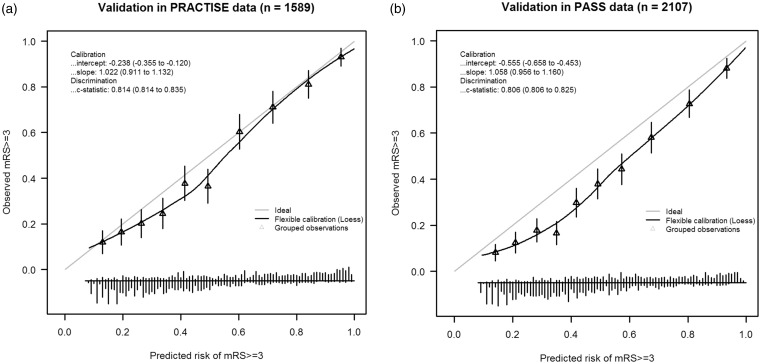

In PRACTISE, the DSS-3 months had an ordinal AUC of 0.74 and an AUC for the cutoff mRS ≥ 3 of 0.81 (95%CI 0.81–0.84) (online Supplemental Table 1). The model predicted 49.4% poor outcome (mRS ≥ 3); whereas the observed probability of poor functional outcome was 45.2%. The calibration slope was 1.022 and the intercept was −0.238, indicating that the model’s predictions of poor outcome were systematically higher than the observed probability of poor outcome (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Calibration plots of the DSS-3 months in (a) PRACTISE and (b) PASS.

DSS: Dutch Stroke Score; PRACTISE: PRomoting ACute Thrombolysis in Ischemic StrokE; PASS: Preventive Antibiotics in Stroke Study.

In PASS, the DSS-3 months had an ordinal AUC of 0.69 and an AUC for the cutoff mRS ≥ 3 of 0.81 (95%CI 0.81–0.83) (online Supplemental Table 1). The predicted probability of poor outcome was 48.6%, compared to an observed probability of poor functional outcome of 38.5%. The calibration slope was 1.058 and the intercept was −0.555, indicating that the model’s predictions of poor outcome were systematically too high (Figure 1(b)). This overestimation was higher than in PRACTISE.

The internal and external validation in the complete cases (PAIS n = 1227, PRACTISE n = 1581, PASS n = 2098) yielded similar results (not shown).

The lower discriminative ability of the DSS-3 months in the external validation cohorts was largely explained by a less heterogeneous case-mix compared to the development cohort. This is illustrated by small differences between the development AUC and case-mix-corrected AUCs (online Supplemental Table 1). The lower discriminative ability in PASS compared to PAIS and PRACTISE was due to both case-mix and differences in predictor effects (relatively large difference between AUC in external validation and case-mix-corrected AUC in PASS).

The final DSS-3 months was developed on the combined data of all three cohorts (n = 4923). The model had an ordinal AUC of 0.73 and an AUC for the cutoff mRS ≥3 of 0.81 (95%CI 0.81–0.83) (online Supplemental Table 1).

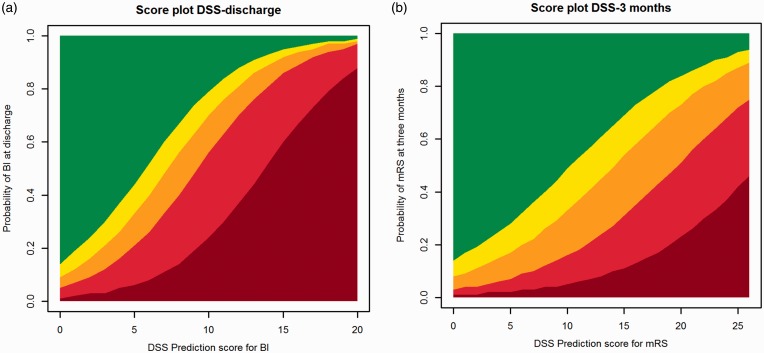

The final models are presented as the DSS score chart (Table 3, and simplified to five outcome classes in Figure 2), with higher scores indicating worse outcome. For example, a patient of 70 years with an NIHSS of 13 and a history of previous stroke and diabetes has a DSS-discharge score of 8 and a predicted probability of 17% for BI 19–20 at discharge and a DSS-3 months score of 13 and a predicted probability of 76% for mRS ≥ 3 at three months (online Appendix 1).

Table 3.

DSS score chart based on ordinal analysis of the BI and mRS. A higher score indicates a worse outcome (lower predicted BI and higher mRS).

| Variable | Points for predicting BI at discharge | Points for predicting mRS score at 3 months |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <60 | 0 | 0 |

| 60–70 | 1 | 2 |

| 70–80 | 2 | 4 |

| 80–90 | 3 | 6 |

| 90+ | 4 | 8 |

| NIHSS | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–4 | 1 | 1 |

| 5–15 | 5 | 5 |

| 16–20 | 10 | 10 |

| 21–42 | 15 | 15 |

| Diabetes | 1 | 2 |

| Previous stroke | – | 2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | – | 1 |

| Total | 0–20 | 0–28 |

BI: Barthel Index; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; DSS: Dutch Stroke Score.

Figure 2.

DSS score charts simplified to five outcome classes of the (a) BI at discharge and (b) mRS at three months. Legend of (a): Dark red=0, Red=1–9, Orange=10–14, Yellow=15–18, Green=19–20 and legend of (b): Dark red=6, Red=4–5, Orange=3, Yellow=2, Green=0–1.

DSS: Dutch Stroke Score; BI: Barthel Index; mRS: modified Rankin Scale.

Discussion

We propose the DSS, consisting of two simple prediction models for disability (BI) at discharge and functional outcome (mRS) at three months after acute ischemic stroke based on clinical information available on admission. The DSS-discharge consists of three variables: age per decade above 60 years, NIHSS per point and diabetes. The DSS-3 months additionally includes previous stroke and atrial fibrillation. Both models showed reasonable performance in internal and external validation.

Relation with previous literature

Previously, several models to estimate the probability of unfavourable outcome after stroke have been developed, with a high variability in endpoints, time between symptom onset and assessment of the variables, and patient populations. Literature reviews have shown that many of these prediction models have methodological shortcomings that limit their use for early discharge planning. For instance, assessment of predictors multiple days after stroke onset18,19 and the use of a dichotomous outcome such as mortality.20–26 In addition, previously developed models were not validated, and hence their use in clinical practice is limited.8,27

One tool has been developed specifically to predict unfavorable discharge destination from the hospital stroke unit. Functional disability, poor sitting balance, depression, cognitive disability and old age were identified as predictors of poor discharge outcome.10 However, this model was only applicable for decision-making at 7–10 days post stroke. Moreover, this study had some methodological shortcomings, including dichotomisation of predictors, a small sample size and dichotomisation of the outcome.

Implications of study findings

Prediction models in acute stroke are useful to inform patients and relatives on prognosis and identify patients at risk for poor outcome before treatment decisions are made.7 On population level, prediction models can be used for adjustment when comparing quality of care for stroke patients across institutions. Additionally, prediction models could be relevant in design and analysis of randomised controlled trials, e.g. for covariate adjustment.28,29 Further, prediction of functional outcome may contribute to discharge planning. If functional outcome is expected to be poor, contextual factors, such as housing circumstances, financial problems and whether or not a patient is living alone, become more important.

We developed the DSS to be used by stroke unit nurses during the first day after admission. In clinical practice, the NIHSS is mostly scored shortly after the administration of alteplase. Therefore, we did not add treatment with alteplase as a covariable to our analysis. Recently, intra-arterial treatment administered within six hours after stroke onset has been shown beneficial in patients with a proximal intracranial arterial occlusion.30 However, the majority (90%) of acutely admitted ischemic stroke patients still receives intravenous alteplase as only treatment. Therefore, the DSS is potentially suitable for use in present neurovascular practice. To facilitate discharge planning in endovascular-treated patients, a next step could be to update the models by including treatment (thrombolysis, thrombectomy or both) as a predictor. Moreover, no imaging or laboratory tests are required for clinicians to be able to use the DSS, which allows bedside use of the models early after admission. The DSS score chart can be easily incorporated in clinical practice since it consists of a few readily obtainable clinical variables at admission. Stroke unit nurses will be able to score all variables, including the NIHSS, provided that they are well trained and certified.

The DSS-discharge still needs to be externally validated to give reliable estimates on model performance and study generalisability.

At external validation, the discriminative ability of the DSS-3 months was generally lower than in the development sample. Discrimination was better in PRACTISE compared to PASS, both for the ordinal analysis of the mRS and for three different cutoffs of the mRS (online Supplemental Table 1). These higher AUCs were partly explained by differences in case-mix, as reflected in the case-mix-corrected AUCs. In addition, the predictor effects were slightly stronger in PRACTISE than in PASS. These differences in regression coefficients were most evident for diabetes and previous stroke, and could be explained by discrepancies in predictor definitions. For instance, in PASS, previous stroke comprised both Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) and ischemic stroke, while in PRACTISE only ischemic stroke was considered. This implicates that the DSS-3 months is valid, but the definitions of the predictors should be identical to those in the development cohort.

The reasonable discriminative ability of the DSS-3 months was associated with an overall overestimation of the probability of poor outcome. This overestimation was higher in PASS compared to PRACTISE, which might be due to the difference in outcome distribution between these cohorts (lower proportion of patients with poor outcome in PASS). This difference is most likely caused by the exclusion of patients with imminent death and neurological deterioration in PASS. The overestimation of the probability of poor outcome implies that the DSS-3 months needs updating (e.g. adjustment of the intercept (recalibration)) before it is suitable for individualised predictions in clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study are the internal and (partial) external validation of the DSS, and the large size of the development and two independent validation cohorts. Even though many models have been developed for prediction of outcome after stroke, the large sample size and the aim of contributing to efficient discharge planning makes that our study has added value compared to already existing evidence. Also, we predicted outcomes over the whole range from no symptoms to death. Furthermore, we used two well-known and widely implemented outcome measures for functional outcome in our models. The BI is a reliable and valid scale to measure ADL.31 Since discharge destination (partially) depends on the patient’s ability to carry out ADL, the BI is a suitable outcome for our model. Additionally, we selected potential predictors based on the literature and clinical knowledge. This is preferred over selection based on the data as the latter may result in overfitting (model perfect for the development data but performing poor in new patients).12 The robustness of our approach is represented in the reasonable performance of the models in internal and external validation.

Several limitations of our study need to be considered. We included only hospitalised patients with an ischemic stroke in our analysis. Consequently, our chart does not apply for patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Further, the development and validation cohorts originated from randomised controlled trials conducted in the Netherlands, potentially limiting the generalisability of the chart. To evaluate the performance of the models beyond the Dutch setting, external validation in observational data from settings with a different healthcare system configuration is necessary. However, the Dutch stroke population is representative for stroke populations in developed countries. Moreover, our external validation cohorts consist of unselected, prospectively included patients, originating from hospitals representative in size, geographic distribution and frequency of stroke treatment procedures. We were able to externally validate the DSS-3 months, but not the DSS-discharge as no data on BI at discharge were available. Also, discharge policy is variable between and within different healthcare systems, which makes it a difficult outcome for prediction purposes. However, these differences in discharge timing resemble the variation in clinical practice. Additionally, in the field of rehabilitation, predicting functional outcome in terms of the mRS has limitations. Important aspects that can contribute to the level of disability and the need for rehabilitation (e.g. pain, communication, cognition) are not entirely covered by the mRS.32 However, the mRS is a widely used outcome measure in stroke management.

The prognostic performance of the DSS after validation could be classified as satisfactory. This does not disqualify the usefulness of the models for clinical practice, because in general, multivariable prediction models are able to incorporate and accurately weigh more factors than a human mind.33 Nevertheless, the results should always be regarded as a mere recommendation and should be placed in the context of the personal circumstances, needs and wishes of the patient. Other factors that are worth considering when planning patients’ discharge are the presence of social support, cognitive disability, the therapeutic needs of the patient and the expected future residence destination (e.g. home or nursing facility).

Conclusion

The DSS has satisfactory performance in predicting BI at discharge and mRS at three months in ischemic stroke patients. If further validated, the DSS may contribute to efficient stroke unit discharge planning alongside patients’ contextual factors (e.g. social support, housing circumstances and cognitive disability) and therapeutic needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Dutch Stroke Score was developed by researchers from the Erasmus MC Rotterdam and validated in data provided by researchers from the Erasmus MC Rotterdam and AMC Amsterdam. The authors wish to thank the investigators and patients participating in the PAIS, PRACTISE and PASS trials.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SD receives revenue from the Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is funded by the Foundation for Neurovascular Research Rotterdam (SNOR, Stichting Neurovasculair Onderzoek Rotterdam). The PAIS study was funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant number 2002B148). The PRACTISE study was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZON-MW, grant number 945–14-217). The PASS study was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZON-MW, grant numbers 171002302 and 016116358), the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant number 2009B095), and the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant).

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

All trial protocols were approved by the local ethics committees of the corresponding centres.

Guarantor

DD.

Contributorship

DD, ES and HF conceived and supervised the study. IR, SD and HF were involved in data analysis. IR and SD wrote the manuscript. MS, HH, MD, WW, PN, DB and GR provided critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. IR and SD contributed equally to this article.

Trial registration

PAIS study – Netherlands Trial Register: NTR2365. PRACTISE study – ISRCTN registry: ISRCTN20405426. PASS study – ISRCTN registry: ISRCTN66140176.

References

- 1.Buddeke J, van Dis I, Visseren FLJ, et al. Ziekenhuisopnamen wegens hart- en vaatziekten In: Buddeke J, van Dis I, Visseren FLJ, et al. (eds) Hart- en vaatziekten in Nederland 2016, cijfers over prevalentie, ziekte en sterfte. Den Haag: Hartstichting, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennisnetwerk CVA Nederland. Benchmarkindicatoren. In: Benchmarkresultaten 2014, rapportage en achtergrondinformatie (2016, accessed 26 June 2017).

- 3.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, et al. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988; 19: 604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahoney FI andBarthel DW.. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965; 14: 61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lees KR, Bath PM, Schellinger PD, et al. Contemporary outcome measures in acute stroke research: choice of primary outcome measure. Stroke 2012; 43: 1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veerbeek JM, Kwakkel G, van Wegen EE, et al. Early prediction of outcome of activities of daily living after stroke: a systematic review. Stroke 2011; 42: 1482–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, van der Windt DA, et al. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 3: prognostic model research. PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Counsell C andDennis M.. Systematic review of prognostic models in patients with acute stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2001; 12: 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.den Hertog HM, van der Worp HB, van Gemert HM, et al. The Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) In Stroke (PAIS) trial: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meijer R, van Limbeek J, Peusens G, et al. The Stroke Unit Discharge Guideline, a prognostic framework for the discharge outcome from the hospital stroke unit. A prospective cohort study. Clin Rehabil 2005; 19: 770–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senn S andJulious S.. Measurement in clinical trials: a neglected issue for statisticians? Stat Med 2009; 28: 3189–3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steyerberg EW. Validation of prediction models. In: Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation and updating. New York: Springer, 2009, pp.299–310.

- 13.Dirks M, Niessen LW, van Wijngaarden JD, et al. Promoting thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2011; 42: 1325–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westendorp WF, Vermeij JD, Zock E, et al. The Preventive Antibiotics in Stroke Study (PASS): a pragmatic randomised open-label masked endpoint clinical trial. Lancet 2015; 385: 1519–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Calster B, Van Belle V, Vergouwe Y, et al. Discrimination ability of prediction models for ordinal outcomes: relationships between existing measures and a new measure. Biom J 2012; 54: 674–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vergouwe Y Moons KG andSteyerberg EW.. External validity of risk models: Use of benchmark values to disentangle a case-mix effect from incorrect coefficients. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 172: 971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steyerberg EW andHarrell FE Jr. Prediction models need appropriate internal, internal-external, and external validation. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 69: 245–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Counsell C Dennis M andMcDowall M.. Predicting functional outcome in acute stroke: comparison of a simple six variable model with other predictive systems and informal clinical prediction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75: 401–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Counsell C, Dennis M, McDowall M, et al. Predicting outcome after acute and subacute stroke: development and validation of new prognostic models. Stroke 2002; 33: 1041–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ntaios G, Faouzi M, Ferrari J, et al. An integer-based score to predict functional outcome in acute ischemic stroke: the ASTRAL score. Neurology 2012; 78: 1916–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weimar C, Konig IR, Kraywinkel K, et al. Age and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale Score within 6 hours after onset are accurate predictors of outcome after cerebral ischemia: development and external validation of prognostic models. Stroke 2004; 35: 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myint PK, Clark AB, Kwok CS, et al. The SOAR (Stroke subtype, Oxford Community Stroke Project classification, Age, prestroke modified Rankin) score strongly predicts early outcomes in acute stroke. Int J Stroke 2014; 9: 278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayis SA, Coker B, Rudd AG, et al. Predicting independent survival after stroke: a European study for the development and validation of standardised stroke scales and prediction models of outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013; 84: 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Donnell MJ, Fang J, D'uva C, et al. The PLAN score: a bedside prediction rule for death and severe disability following acute ischemic stroke. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172: 1548–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saposnik G, Kapral MK, Liu Y, et al. IScore: a risk score to predict death early after hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke. Circulation 2011; 123: 739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith EE, Shobha N, Dai D, et al. Risk score for in-hospital ischemic stroke mortality derived and validated within the Get With the Guidelines-Stroke Program. Circulation 2010; 122: 1496–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwakkel G, Wagenaar RC, Kollen BJ, et al. Predicting disability in stroke–a critical review of the literature. Age Ageing 1996; 25: 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, et al. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Statist Med 2002; 21: 2917–2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roozenbeek B Lingsma HF andMaas AI.. New considerations in the design of clinical trials for traumatic brain injury. Clin Investig Lond 2012; 2: 153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016; 387: 1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duffy L, Gajree S, Langhorne P, et al. Reliability (inter-rater agreement) of the Barthel Index for assessment of stroke survivors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2013; 44: 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berzina G, Sveen U, Paanalahti M, et al. Analyzing the modified Rankin scale using concepts of the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2016; 52: 203–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tversky A andKahneman D.. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981; 211: 453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.