Abstract

Purpose

Non-adherence to secondary preventative medications after stroke is relatively common and associated with poorer outcomes. Non-adherence can be due to a number of patient, disease, medication or institutional factors. The aim of this review was to identify factors associated with non-adherence after stroke.

Method

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting factors associated with medication adherence after stroke. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, CENTRAL and Web of Knowledge. We followed PRISMA guidance. We assessed risk of bias of included studies using a pre-specified tool based on Cochrane guidance and the Newcastle–Ottawa scales. Where data allowed, we evaluated summary prevalence of non-adherence and association of factors commonly reported with medication adherence in included studies using random-effects model meta-analysis.

Findings

From 12,237 titles, we included 29 studies in our review. These included 69,137 patients. The majority of included studies (27/29) were considered to be at high risk of bias mainly due to performance bias. Non-adherence rate to secondary preventative medication reported by included studies was 30.9% (95% CI 26.8%–35.3%). Although many factors were reported as related to adherence in individual studies, on meta-analysis, absent history of atrial fibrillation (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.72–1.5), disability (OR 1.27, 95% CI 0.93–1.72), polypharmacy (OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.9–1.9) and age (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96–1.14) were not associated with adherence.

Discussion

This review identified many factors related to adherence to preventative medications after stroke of which many are modifiable. Commonly reported factors included concerns about treatment, lack of support with medication intake, polypharmacy, increased disability and having more severe stroke.

Conclusion

Understanding factors associated with medication taking could inform strategies to improve adherence. Further research should assess whether interventions to promote adherence also improve outcomes.

Keywords: Stroke, medication, adherence, prevalence, predictors, transient ischaemic attack

Introduction

It is recognised that adherence to secondary preventative medications after stroke is variable; in some studies more than half of participants stopped taking their prescribed drugs 1–2 years after the stroke incident.1–3 Use of the secondary prevention strategies has been reported to result in 80% reduction in the risk of stroke recurrence, vascular events or death4,5 and poor adherence is related to adverse outcomes.6–8

Many factors interfere with the ability of stroke patients to regularly take their medications. Stroke survivors may have disability or cognitive issues which make them unable to self-administer medication.9–11 Personal beliefs and preferences may also impact adherence.10 Medication factors also affect adherence. Drugs such as anti-coagulants typically have less adherence than anti-platelets11 and cost of medications is also of potential importance.9 Health care system failure exists through lack of access to health care and inadequate communication with health care providers.12

Several studies have attempted to identify barriers to adherence to medication after stroke. Patients with stroke expressed that concerns about prescribed medication and unawareness of the rationale of treatment as primary reasons for non-adherence.13 We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that assessed predictive factors for adherence to preventative medications in patients with stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

Methodology

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines14 for design, conduct and reporting. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42015027531).

Search strategy and study selection

We generated search strings based on concepts of ‘Stroke’ and ‘Medication Adherence.’ We focussed on MeSH terms and other controlled vocabulary (available in the supplementary appendix, which can be found online with this review). Two independent reviewers (SA and WD) searched Web of Knowledge, EMBASE, MEDLINE (both using Ovid), CINAHL, PsycINFO (both in EBSCOhost) and CENTRAL (Cochrane Library). Initially, titles were reviewed and possibly eligible articles were listed for abstract review. These were then retrieved for entire text review by SA. We also reviewed reference lists of included studies and related reviews to detect additional reports.

Eligibility criteria

We only included studies published in English. Studies had to include adults (aged ≥ 18 years) who had suffered stroke or TIA and were prescribed medication for the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events. Studies had to assess factor(s) that influenced medication adherence. Where disagreement arose regarding study eligibility, a consensus meeting was arranged with an arbitrator (JD). We excluded from this review studies that did not include a measure of medication adherence, studies that assessed non-pharmacological preventative strategies only or did not include stroke or TIA patients.

Data extraction

We designed a data extraction form that summarised information on study characteristics, inclusion criteria, sample size, secondary preventative medications, method used to measure adherence and predictive factors. We did not contact the study authors for missing information or for clarification.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in included studies using a pre-specified tool generated using Cochrane Library tool for assessing risk of bias15 and the Newcastle–Ottawa scales.16 Two independent reviewers (SA and JD) assessed risk of bias and met to finalise the assessment. Disagreement was resolved via discussion until reaching a mutual agreement. We considered studies as of high quality if they met the criteria for all the assessment domains (selection, performance, attrition, reporting and confounders).

Data synthesis and analysis

We categorised preventative medications as anti-coagulants, anti-platelet, blood pressure or lipid lowering drugs. Some studies also reported adherence to the overall medication regimen without specification of medication classes. We listed predictive factors, significance (odds or hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals) and the type of analysis used. We used the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of predictive factors of non-adherence, which categorised these into five domains:17

– Patient related factors

– Social and economic related factors

– Therapy-related factors

– Health system or health care team related factors and

– Condition (stroke)-related factors

We described included studies and factors reported to be significant using a narrative review. Where a factor was assessed in more than three studies we described a summary value using random-effects models meta-analyses. We also described summary measures of medication non-adherence across non-case control studies. These analyses used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (CMA, version 2.0, Biostat Inc).

Results

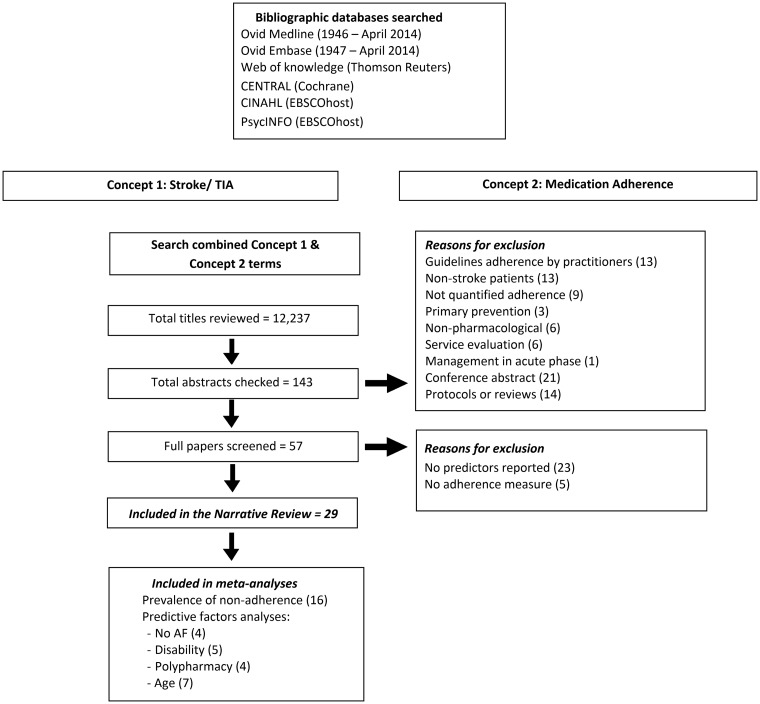

The search was completed in April 2014 and identified a total of 12,237 titles. Title review identified 143 papers for abstract review. Of these 57 were retrieved for full-text review. We identified 29 of these as meeting our eligibility criteria (Figure 1).1,2,9–12,18–40

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Risk of bias across included studies

Studies included in this review were all of high risk of bias (except two34,36) mainly because details on performance bias, represented by blinding of outcome assessor, were not reported. It was also unclear whether there was a selective reporting of the outcomes in a study.23 Twelve studies were non-controlled.2,9,10,18–20,22,28,32,38–40 In addition, most studies used a subjective method to monitor adherence which has been reported to overestimate patients’ adherence.41,42 More details on other sources of bias in included studies are available in the supplementary appendix.

Narrative review

Description of eligible studies

The 29 included studies were observational studies of which 14 were prospective cohorts,1,2,9,10,18,20,24,26,32,35,36,38–40 4 were retrospective cohorts,22,28,33,34 9 used a cross-sectional design11,12,21,25,27,29–31,37 and two performed a case-control analysis.19,23 Details of study characteristics can be found in Table 1. The total number of participants in the included studies was 69,137. Reported non-adherence rate ranged between 11.3%39 and 45.2%.30

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Design | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Sample size | Medication classes | Adherence assessment measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arif et al.21 | Cross-sectional | First-time stroke | MI Non-ischaemic or non-haemorrhagic TIA | 298 | AP AH LLD | Telephone interview |

| Burke et al.22 | Retrospective cohort | First-time IS | Previous cardiac condition Previous AT | 1413 | AP | Prescription refill |

| Bushnell et al.18 | Observational cohort, 3 months | IS or TIA | – | 2598 | AP AC AH LLD | Telephone interview |

| Bushnell et al.18 | Longitudinal study, 1 year | IS or TIA | – | 2457 | AP AC AH LLD | Telephone interview |

| Chambers et al.23 | Case-control study | First- time IS | Institutional living | 26 | Not specified | MARS and BMQ |

| Choi-Kwon et al.24 | Observational cohort, 1–5 years | Early-onset stroke patients (onset between ages of 15–45 years) | HS TIA Severe medical conditions Previous stroke | 256 | AH | Patient interview |

| Coetzee et al.25 | Cross-sectional at 6 weeks | Completed rehabilitation program | – | 26 (compared to 29 amputee patients) | All classes | Patient interview and pill count |

| De Schryver et al.26 | Cohort study, 1–2 years | Patients in the Dutch TIA Trial and the Stroke Prevention In Reversible Ischaemia Trial | – | 3796 (aspirin) and 651 (AC) | Aspirin AC | Patient interview and pill count |

| Edmondson et al.27 | Cross-sectional | Age > 40 years Stroke or TIA | Institutional living Pregnant Aphasia Cognitive impairment | 535 | AT AH LLD | MMAS and BMQ |

| Glader et al.2 | Prospective observational study, 2 year | Patients in the Swedish Stroke Register | – | 24,024 | AP AC AH LLD | Prescription refill |

| Huang et al.28 | Retrospective cohort, 1 year | IS or TIA | In-hospital stroke | 11,050 | AT AH LLD | Prescription refill |

| Ji et al.29 | Cross-sectional, at 3 months | IS or TIA | – | 9998 | AP AC AH LLD | Telephone interview |

| Ke et al.30 | Cross-sectional | Cerebral infarction TIA | – | 1240 | Aspirin | Telephone interview |

| Kronish et al.31 | Cross-sectional | Stroke or TIA in the past 5 years | Institutional living Pregnant Aphasia Cognitive impairment | 535 | Not specified | MMAS |

| Kronish et al.12 | Cross-sectional study | Stroke or TIA Age ≥ 40 years | Aphasia Cognitive impairment Pregnant Institutional living | 600 | Not specified | MMAS |

| Levine et al.19 | Case-control study | Stroke Age ≥ 45 years Noninstitutionalized | – | 8673 | Not specified | Questionnaire |

| Lopes et al.32 | Longitudinal study, 1 year | IS or TIA with AF in Get With The Guidelines (GWTG)–Stroke registry & Adherence eValuation After Ischemic Stroke Longitudinal (AVAIL) registry | Bleeding Palliative-care Death or transfer from hospital | 291 | AC | Patient interview |

| Lummis et al.9 | Cohort study, 1 year | Stroke patients in the Stroke Outcome Study | – | 420 | AT AH LLD | Self-reported adherence |

| O’Carroll et al.10 | Longitudinal study, 1 year | First-time IS Responsible for own medication | Institutional living | 180 | AH Aspirin LLD | MARS, BMQ and urinary- salicylate level |

| Østergaard et al.33 | Retrospective cohort | Suspected stroke | HS | 503 | AP | Prescription refill |

| Østergaard et al.34 | Retrospective cohort, 1.7 years | TIA | Prior TIA or stroke & previous AC | 594 | AP | Prescription refill |

| Rodriguez et al.35 | Longitudinal study, 1 year | IS or TIA GWTG-Stroke program | – | 2720 | AP AC AH LLD | Telephone interview |

| Sappok et al.36 | Prospective observational study, 1 year | IS or TIA | Haemorrhage Migraine Epilepsy | 470 | AT | Telephone interview |

| Sjölander et al.38 | Prospective observational study | Ischemic stroke in the Swedish Stroke Register | – | 18,349 | AH | Medication refill |

| Sjölander et al.37 | Cross-sectional | Stroke | Institutional-living | 578 | Not specified | MARS |

| Thrift et al.20 | Prospective cohort, 10 years | Stroke | Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 1241 | AT AH LLD | Self-reported adherence |

| Wang et al.11 | Cross-sectional, at 1 year | TIA or a cerebral infarction | Haemorrhage Migraine Epilepsy | 722 | AT | Telephone interview |

| Weimar et al.39 | Observational cohort, 1–2 years | Cerebrovascular disease with AF | Intracerebral haemorrhage | 293 | AC | Patient interview |

| Xu et al.40 | Prospective cohort, 1-year | Stroke Hypertension | – | 7880 | AH | Telephone interview |

AC: anti-coagulants; AF: atrial fibrillation; AH: anti-hypertensives; AP: anti-platelets; AT: anti-thrombotics; BMQ: beliefs about medicines questionnaire; HS: haemorrhagic stroke; IS: ischaemic stroke; LLD: lipid-lowering drugs; MARS: medication adherence report scale; MMAS: Morisky-medication adherence scale.

Description of predictive factors for non-adherence

Two studies showed no difference in predictors within groups. One compared factors between rural and urban residence35 and the other compared patients living in different income quintiles.28 Factors related to non-adherence in the other 27 studies are classified below and detailed in the supplementary appendix.

Patient-related factors

Younger age at time of stroke was associated with reduced medication adherence in seven studies9,10,18,24,26,33,34 whereas younger age reported to associate with better adherence in five studies.2,29,36,39,40 Three studies reported that female sex predicted decreased adherence2,29,32 whereas one reported the opposite.37

Other patient-related factors included having concerns about medication, which associated with decreased adherence in four studies,10,12,27,30 or when patients perceived no benefit of treatment as reported in one study.10 On the other hand, when patients had positive beliefs about medication23,25,37 and indicated they were aware of the consequence of not taking prescribed medication,23 these factors were associated with enhanced adherence to medication.

Socioeconomic factors

Three studies indicated that having some sort of education21,40 or settled work status18 were associated with improved adherence. Four studies reported that the presence of patient carer or supporter also predicted better adherence.2,23,25,29 Two studies reported that living at care institution other than home was associated with worsened adherence.2,39

Therapy-related factors

Disease- or health-related factors that predicted non-adherence included disability,1,9,18,29,37,39 reduced cognition function,10,23,25,37 poor quality of life2,11,18 and low mood.2,25 Smoking9,34 and alcohol consumption34,40 were also predictors of medication non-adherence.

Existence of co-morbidities at the time of stroke associated with improved adherence to treatment. These included history of hypertension,18,29,34 diabetes,2,18 dyslipidaemia,18,21,40 coronary artery disease18,40 or myocardial infarction.18,33 Conversely, the absent history of atrial fibrillation was associated with better adherence.2,18,29,36,40

Prescribed regimen factors that predicted enhanced adherence included understanding of medication rationale,1,18,23,30 awareness of duration of treatment,30 knowledge of how to refill prescription,18 previous treatment by the same medication class,2,38,40 prescription and education at hospital discharge after the incident.20 Also, development of medication routine23 and use of compliance aid by patient.1

Medication regimen factors which associated with reduced adherence included cost of medication9,19,22 and number and frequency of prescribed drugs.1,9,18,29

Health system or caregiver-related factors

Caregiver-related factors included prescriber speciality (e.g. neurologist).1 Patient–caregiver relationship factors included language barrier, low trust, perceived discrimination, inadequate continuity of care1 and inadequate communication of information regarding prescribed regimen.30

Institution factors associated with better adherence included treating facility i.e. treated in stroke unit,2,37 treated in academic hospital29 and hospital size.18 Additionally, arrangement of medical insurance11,24 and accessible health care facility2,12 predicted enhanced adherence.

Stroke-related factors

Stroke-related factors that predicted non-adherence included delay from onset of symptoms to evaluation,34 symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),27,31 more severe stroke,33,36,39,40 previous stroke incidence2,9,37 and time from stroke onset.27 Stroke subtype was another predictor of non-adherence e.g. ischaemic stroke versus Tia,29 cardio-embolic36 and haemorrhagic stroke.2 Nevertheless, factors like reduced cognition, disability and poor quality of life could also be stroke-related.

Meta-analysis

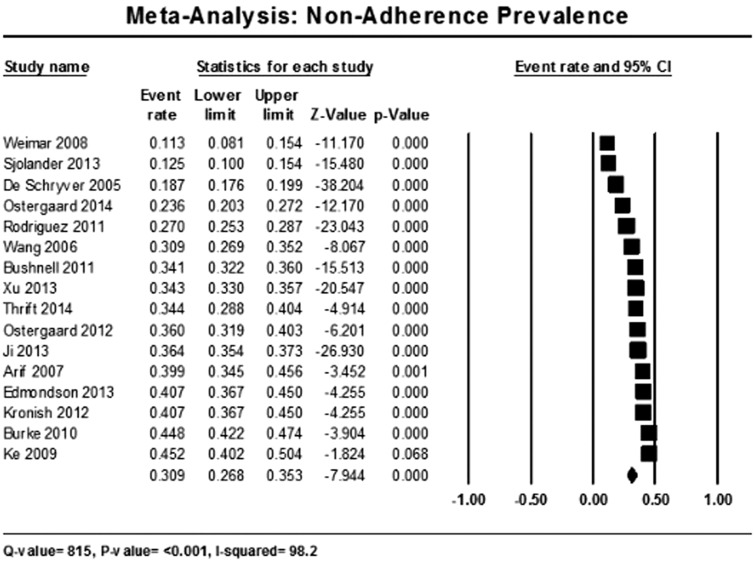

Sixteen studies were eligible for the meta-analysis of prevalence of non-adherence as they provided a measure of medication non-adherence rate.1,11,20–22,26,27,29–31,33–35,37,39,40 The rate of non-adherence was 30.9% (95% CI 26.8–35.3%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of prevalence of non-adherence within included studies.

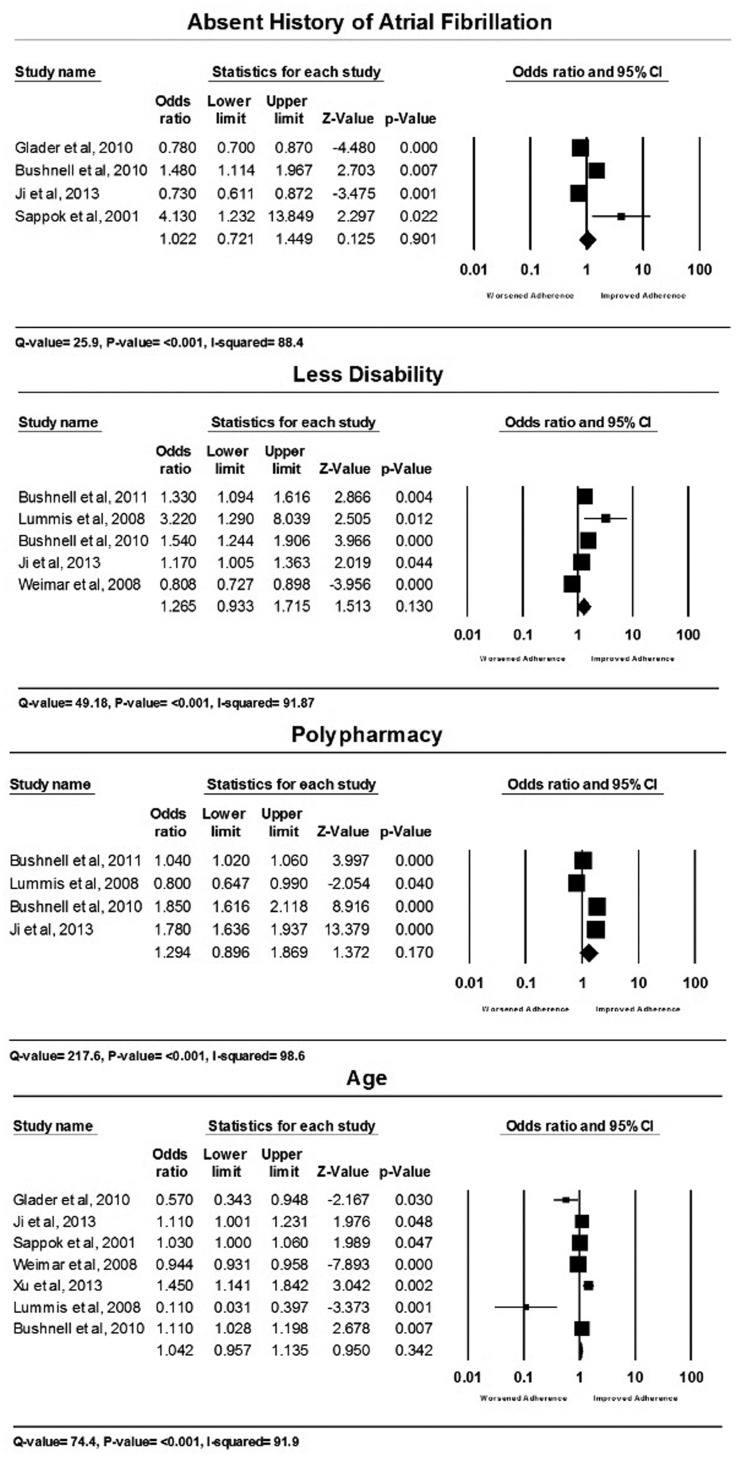

For the meta-analysis of effect of factors on medication adherence, four factors were eligible which were: absent history of AF (4 studies2,18,29,36), disability (5 studies1,9,18,29,39), polypharmacy (4 studies1,9,18,29) and age of the patient (7 studies2,9,18,29,36,39,40). Meta-analyses of these factors showed that these factors did not significantly associate with medication adherence (no AF OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.72–1.5 (p = 0.9); disability OR 1.27, 95% CI 0.93–1.72 (p = 0.13); polypharmacy OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.9–1.9 (p = 0.17); age OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96–1.14 (p = 0.34)). Forest plots for each factor analysis are available in Figure 3. There was considerable heterogeneity across all studies included in the meta-analyses (all I2 > 88%).

Figure 3.

Meta-analyses of predictive factors.

Discussion

In this review, we identified factors associated with adherence behaviour to secondary preventative medication after stroke or TIA. As stated by the WHO, patients alone used to be held responsible for non-adherence; however, it has been identified that other factors including the health care system or providers can also impact on non-adherence.17

Many factors associated with enhanced adherence to secondary preventative medication including positive beliefs about medication.23,25,37 This also included patients who encountered lower cost of medications9,19,22 or had medical insurance.11,24

Most of the published work focusses on patient and drug specific factors as determinants of adherence. The importance of institution or health care factors should not be neglected. Prescribing and educating patients on medication for secondary prevention before hospital discharge was linked to improved adherence.20 Numerous studies showed that in-hospital initiation of secondary preventative medication resulted in higher rates of adherence.20,43,44 This should include details on the purpose of treatment and regimen dosage.1,18,23,30 Also, patients should be ensured adequate continuity of care1 and access to health care after stroke.2,12 These simple measures could improve clinical outcomes.

Nonetheless, stroke patients with disability,1,9,18,29,37,39 reduced cognitive function,10,23,25,37 increased number of prescribed medication,1,9,18,29 concerns about treatment,10,12,27,30 history of stroke2,9,37 or more severe stroke event33,36,39,40 commonly showed reduced adherence to treatment.

Factors reported in this review were similar to those reported to correlate with adherence to medication in cardiovascular disease including coronary heart disease and acute coronary syndrome45–48 and to medications in general.49,50

Two patient-related factors were controversial in predicting adherence to secondary preventative medication, age at the time of stroke incident2,9,10,18,24,29,33,34,36,39,40 and sex of the patient.2,29,32,37 A study that assessed differences in prescribing secondary preventative drugs to stroke patients found significant differences where women were less likely to receive all recommended secondary preventative medication classes than men. However, younger patients were less likely to receive anti-platelet treatment.51 These factors are, however, non-reversible or amendable thus health care practitioners need to not hesitate with secondary prevention therapy if prescribing does not contrast with evidence-based recommendations.

In the meta-analysis of prevalence of non-adherence, we found non-adherence to be high with almost a third of stroke patients not receiving adequate secondary prevention. This clearly indicates importance for applying interventions that would improve adherence especially in the group vulnerable for non-adherence.

Despite the fact that none of the factors meta-analysed in this review showed significant association with medication adherence, caution should be taken not to interpret that association does not exist. This is explainable by the heterogeneity within included studies which was due to the considerable variation in subjects’ inclusion criteria, factors reported, medication classes, definition of adherence or compliance and the analysis used.

Limitations

There were several limitations of this review. Available data are heterogeneous as a result of lack of universal reporting of medication adherence. In addition, there was no standardised scale to critically appraise type of included studies. Also, inclusion and exclusion specification could have influenced reporting predictors e.g. if a study excluded participants of specific age or population who are known to have a high risk of non-adherence.

Implication for practice and future research

In this review, we aimed to identify factors correlated with adherence to secondary preventative medication after stroke. When clinicians are able to discuss barriers of adherence with their patients, they could ensure reducing the burden of treatment on their patients. It is also essential to identify reversible factors, e.g. misbeliefs or complex regimens, as these can be addressed. On the other hand, knowing factors that encourage stroke patients to adhere, clinicians would also be able to support stroke patients who are already adhering to maintain a good level of adherence. Researchers need to identify which interventions work best in supporting stroke patients to safely continue treatment with secondary preventative medication. Also, measures for detecting and tackling difficulties for medication administration after stroke need to be tested and implemented.

Conclusion

Potential stroke patients with identified factors that predicted non-adherence require further attention, continuous encouragement and support with medication intake. Factors frequently reported to affect adherence included concerns about treatment regimen, increased disability, suffering severe stroke, polypharmacy and complex medication regimen. Focus should be more on reversible factors such as correcting misbeliefs about medication and providing convenient regimen. Stroke patients with disability or reduced cognition should be given additional care.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Quinn is supported by a Joint Stroke Association and Chief Scientist Office Senior Clinical Lectureship.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent

N/A

Ethical approval

N/A, not required

Guarantor

JD

Contributorship

SA– review protocol, literature research, data collection, data analysis and interpretation; figures, tables and quality assessment of papers; writing of the manuscript. TQ – review protocol, data interpretation and revision of manuscript. WD – review protocol and literature research. MW – revision of manuscript. JD – supervision, review protocol, data interpretation, quality assessment of papers and revision of manuscript.

References

- 1.Bushnell CD, Olson DM, Zhao X, et al. Secondary preventive medication persistence and adherence 1 year after stroke. Neurology 2011; 77: 1182–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glader EL, Sjolander M, Eriksson M, et al. Persistent use of secondary preventive drugs declines rapidly during the first 2 years after stroke. Stroke 2010; 41: 397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mouradian MS, Majumdar SR, Senthilselvan A, et al. How well are hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking managed after a stroke or transient ischemic attack? Stroke 2002; 33: 1656–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hackam DG, Spence JD. Combining multiple approaches for the secondary prevention of vascular events after stroke: A quantitative modeling study. Stroke 2007; 38: 1881–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JH, Ovbiagele B. Optimal combination treatment and vascular outcomes in recent ischemic stroke patients by premorbid risk level. J Neurol Sci 2015; 355: 90–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colivicchi F, Bassi A, Santini M, et al. Discontinuation of statin therapy and clinical outcome after ischemic stroke. Stroke 2007; 38: 2652–2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumbhani DJ, Steg PG, Cannon CP, et al. Adherence to secondary prevention medications and four-year outcomes in outpatients with atherosclerosis. Am J Med 2013; 126: 693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perreault S, Yu AY, Cote R, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive agents after ischemic stroke and risk of cardiovascular outcomes. Neurology 2012; 79: 2037–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lummis HL, Sketris IS, Gubitz GJ, et al. Medication persistence rates and factors associated with persistence in patients following stroke: A cohort study. BMC Neurol 2008; 8: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Carroll R, Whittaker J, Hamilton B, et al. Predictors of adherence to secondary preventive medication in stroke patients. Ann Behav Med 2011; 41: 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Wu D, Wang Y, et al. A survey on adherence to secondary ischemic stroke prevention. Neurol Res 2006; 28: 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kronish IM, Diefenbach MA, Edmondson DE, et al. Key barriers to medication adherence in survivors of strokes and transient ischemic attacks. J Gen Intern Med 2013; 28: 675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauler S, Jacquin-Courtois S, Haesebaert J, et al. Barriers and facilitators for medication adherence in stroke patients: A qualitative study conducted in French neurological rehabilitation units. Eur Neurol 2014; 72: 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013.

- 17.Burkhart PV, Sabate E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. J Nurs Scholarsh 2003; 35: 207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushnell CD, Zimmer LO, Pan W, et al. Persistence with stroke prevention medications 3 months after hospitalization. Arch Neurol 2010; 67: 1456–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine DA, Morgenstern LB, Langa KM, et al. Recent trends in cost-related medication nonadherence among stroke survivors in the United States. Ann Neurol 2013; 73: 180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thrift AG, Kim J, Douzmanian V, et al. Discharge is a critical time to influence 10-year use of secondary prevention therapies for stroke. Stroke 2014; 45: 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arif H, Aijaz B, Islam M, et al. Drug compliance after stroke and myocardial infarction: A comparative study. Neurol India 2007; 55: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke JP, Sander S, Shah H, et al. Impact of persistence with antiplatelet therapy on recurrent ischemic stroke and predictors of nonpersistence among ischemic stroke survivors. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers JA, O'Carroll RE, Hamilton B, et al. Adherence to medication in stroke survivors: A qualitative comparison of low and high adherers. Br J Health Psychol 2011; 16: 592–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi-Kwon S, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Compliance with risk factor modification: Early-onset versus late-onset stroke patients. Eur Neurol 2005; 54: 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coetzee N, Andrewes D, Khan F, et al. Predicting compliance with treatment following stroke: A new model of adherence following rehabilitation. Brain Impair 2008; 9: 122–139. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Schryver EL, van Gijn J, Kappelle LJ, et al. Non-adherence to aspirin or oral anticoagulants in secondary prevention after ischaemic stroke. J Neurol 2005; 252: 1316–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edmondson D, Horowitz CR, Goldfinger JZ, et al. Concerns about medications mediate the association of posttraumatic stress disorder with adherence to medication in stroke survivors. Br J Health Psychol 2013; 18: 799–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang K, Khan N, Kwan A, et al. Socioeconomic status and care after stroke: Results from the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Stroke 2013; 44: 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji R, Liu G, Shen H, et al. Persistence of secondary prevention medications after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in Chinese population: data from China National Stroke Registry. Neurol Res 2013; 35: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ke XJ, Yu YF, Guo ZL, et al. The utilization status of aspirin for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. Chin Med J 2009; 122: 165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kronish IM, Edmondson D, Goldfinger JZ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and adherence to medications in survivors of strokes and transient ischemic attacks. Stroke 2012; 43: 2192–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopes RD, Shah BR, Olson DM, et al. Antithrombotic therapy use at discharge and 1 year in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute stroke: Results from the AVAIL Registry. Stroke 2011; 42: 3477–3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostergaard K, Hallas J, Bak S, et al. Long-term use of antiplatelet drugs by stroke patients: A follow-up study based on prescription register data. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 68: 1631–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostergaard K, Madsen C, Liu ML, et al. Long-term use of antiplatelet drugs by patients with transient ischaemic attack. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 70: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez D, Cox M, Zimmer LO, et al. Similar secondary stroke prevention and medication persistence rates among rural and urban patients. J Rural Health 2011; 27: 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sappok T, Faulstich A, Stuckert E, et al. Compliance with secondary prevention of ischemic stroke: A prospective evaluation. Stroke 2001; 32: 1884–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sjölander M, Eriksson M and Glader E-L. The association between patients’ beliefs about medicines and adherence to drug treatment after stroke: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open 2013; 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Sjolander M, Eriksson M, Glader EL. Few sex differences in the use of drugs for secondary prevention after stroke: A nationwide observational study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 2012; 21: 911–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weimar C, Benemann J, Katsarava Z, et al. Adherence and quality of oral anticoagulation in cerebrovascular disease patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Neurol 2008; 60: 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu J, Ju Y, Wang C, et al. Patterns and predictors of antihypertensive medication used 1 year after ischemic stroke or TIA in urban China. Patient Prefer Adher 2013; 7: 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL, et al. Can simple clinical measurements detect patient noncompliance? Hypertension 1980; 2: 757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephenson BJ, Rowe BH, Haynes R, et al. Is this patient taking the treatment as prescribed? JAMA 1993; 269: 2779–2781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ovbiagele B, Saver JL, Fredieu A, et al. In-hospital initiation of secondary stroke prevention therapies yields high rates of adherence at follow-up. Stroke 2004; 35: 2879–2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Touze E, Coste J, Voicu M, et al. Importance of in-hospital initiation of therapies and therapeutic inertia in secondary stroke prevention: IMplementation of Prevention After a Cerebrovascular evenT (IMPACT) Study. Stroke 2008; 39: 1834–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stafford L, Jackson HJ, Berk M. Illness beliefs about heart disease and adherence to secondary prevention regimens. Psychosom Med 2008; 70: 942–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byrne M, Walsh J, Murphy AW. Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: Patient beliefs and health-related behaviour. J Psychosom Res 2005; 58: 403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen LaPointe NM, Ou F-S, Calvert SB, et al. Association between patient beliefs and medication adherence following hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J 2011; 161: 855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: Its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 2009; 119: 3028–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, et al. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient’s perspective. Therap Clin Risk Manage 2008; 4: 269–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clinic Proc 2011; 86: 304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simpson CR, Wilson C, Hannaford PC, et al. Evidence for age and sex differences in the secondary prevention of stroke in Scottish primary care. Stroke 2005; 36: 1771–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.