Abstract

Background

It has been shown that intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ICAS) has heterogeneous features in terms of plaque instability and vascular remodeling. Therefore, quantitative information on the changes of intracranial atherosclerosis and lenticulostriate arteries (LSAs) may potentially improve understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying stroke and may guide the treatment and work-up strategies. Our present study aimed to use a novel whole-brain high-resolution cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (WB-HRCMR) to assess both ICAS plaques and LSAs in recent stroke patients.

Methods

Twenty-nine symptomatic and 23 asymptomatic ICAS patients were enrolled in this study from Jan 2015 through Sep 2017 and all patients underwent WB-HRCMR. Intracranial atherosclerotic plaque burden, plaque enhancement volume, plaque enhancement index, as well as the number and length of LSAs were evaluated in two groups. Enhancement index was calculated as follows: ([Signal intensity (SI)plaque/SInormal wall on post-contrast imaging] − [SIplaque/SInormal wall on matched pre-contrast imaging])/(SIplaque / SInormal wall on matched pre-contrast imaging). Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the independent high risk plaque and LSAs features associated with stroke.

Results

Symptomatic ICAS patients exhibited larger enhancement plaque volume (20.70 ± 3.07 mm3 vs. 6.71 ± 1.87 mm3 P = 0.001) and higher enhancement index (0.44 ± 0.08 vs. 0.09 ± 0.06 P = 0.001) compared with the asymptomatic ICAS. The average length of LSAs in symptomatic ICAS (20.95 ± 0.87 mm) was shorter than in asymptomatic ICAS (24.04 ± 0.95 mm) (P = 0.02). Regression analysis showed that the enhancement index (100.43, 95% CI − 4.02-2510.96; P = 0.005) and the average length of LSAs (0.80, 95% CI − 0.65-0.99; P = 0.036) were independent factors for predicting of stroke.

Conclusion

WB-HRCMR enabled the comprehensive quantitative evaluation of intracranial atherosclerotic lesions and perforating arteries. Symptomatic ICAS had distinct plaque characteristics and shorter LSA length compared with asymptomatic ICAS.

Keywords: Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis, High-resolution cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging, Stroke, Lenticulostriate arteries

Background

Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ICAS) is one of the most common causes of ischemic stroke, which is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates in Asian countries [1–4]. The initial and follow-up assessment of stroke patients rely mostly upon the evaluation of luminal stenosis via several methods, including transcranial Doppler (TCD), computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) [5–8]. Recently, high-resolution cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (HR-CMR) has been used to directly depict intracranial vessel wall plaques [9, 10]. Two-dimensional imaging techniques were commonly used for HR-CMR to assess intracranial atherosclerotic plaque morphology and plaque composition [11–13]. However, limited spatial temporal resolution hampered its application in quantitative measurement of vessel wall dimensions and visualization of lenticulostriate arteries (LSAs). Several studies have demonstrated that flow-sensitive black blood magnetic resonance angiography (FSBB-MRA) based on 3D gradient-echo sequence can be specifically used to visualize LSAs [14–16]. Our recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of whole-brain high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (WB-HRCMR),which enables combined evaluation of plaque and LSAs in one image setting [17, 18]. Thus, in this study, we aimed to use WB-HRCMR to quantitatively investigate different features of plaque and LSAs in symptomatic versus asymptomatic ICAS groups.

Methods

Study population

From January 2015 to September 2017, consecutive symptomatic and asymptomatic ICAS patients who were admitted to or visit the Department of Neurology of our hospital were consecutively recruited. The inclusion criteria: (1) age 18–80 years old; (2) symptomatic ICAS referred to first time acute ischemic stroke in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory identified by diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) performed within 72 h of symptom onset, and asymptomatic ICAS referred to patients who were diagnosed with other diseases without history of stroke but had MCA stenosis confirmed on image screening; (3) All enrolled subjects had moderate (stenosis: 50–69%) or severe (stenosis: 70–99%) MCA stenosis, confirmed by MRA, CTA, or digital subtraction angiography. The exclusion criteria included: (1) DWI with lacunar infarction: cerebral infarction in LSAs territory involving less than two layers or the diameter of the infarction < 15 mm; (2) coexistent ipsilateral internal carotid stenosis; (3) preexisting conditions such as vasculitis, moyamoya disease, dissection, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS); (4) evidence of cardioembolism (e.g., arterial fibrillation, mechanical prosthetic valve disease, sick sinus syndrome, dilated cardiomyopathy). All patients underwent WB-HRCMR within 2 weeks of symptom onset. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

WB-HRCMR

All patients underwent WB-HRCMR with a 3-Tesla system (Magnetom Verio; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) and a standard 32-channel head coil. WB-HRCMR was performed at both pre-contrast and post-contrast states by using a 3D T1-weighted whole-brain vessel wall CMR technique known as inversion-recovery (IR) prepared SPACE (Sampling Perfection with Application-optimized Contrast using different flip angle Evolutions) [17, 18], with the following parameters: TR/TE = 900/15 ms; field of view = 170 × 170 mm2; 240 slices with slice thickness of 0.53 mm; voxel size = 0.53 × 0.53 × 0.53 mm3; scan time = 8 min. The CMR contrast agent, gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist; Schering, Berlin, Germany), was injected through an antecubital vein (0.1 mmol per kilogram of body weight), and WB-HRCMR was repeated 5 min after injection was performed.

WB-HRCMR image analysis

Evaluation of WB-HRCMR was conducted in consensus by two experienced neuroradiologists blinded to the patient’s clinical details. Commercial software (Vessel Analysis, Oak Medical Imaging Technologies, Inc.) with 3D multi-planar reformation and region-of-interest (ROI) signal measurement functionalities was used for quantitative analysis. A plaque was defined as thickening of the vessel wall using its adjacent proximal, distal, or contralateral vessel segment as a reference. A culprit plaque was defined as (1) the only lesion within the vascular vicinity of the stroke or (2) the most stenotic lesion when multiple plaques were present within the same vascular territory of the stroke. The vessel area (VA) and lumen area were measured by manually tracing vessel and lumen boundaries. The difference between VA and lumen area was the wall area (WA). Stenosis degree was defined as (1-lesion lumen area/reference lumen area) × 100%. The remodeling index (RI) was calculated as the ratio of the lesion VA to the reference VA. The wall area index was defined as the ratio of the lesion WA to the reference WA. And the plaque burden was calculated as WA/VA × 100%. The mean signal intensity (SI) values of culprit plaques and reference vessel wall were measured on pre- and post-contrast WB-HRCMR images.

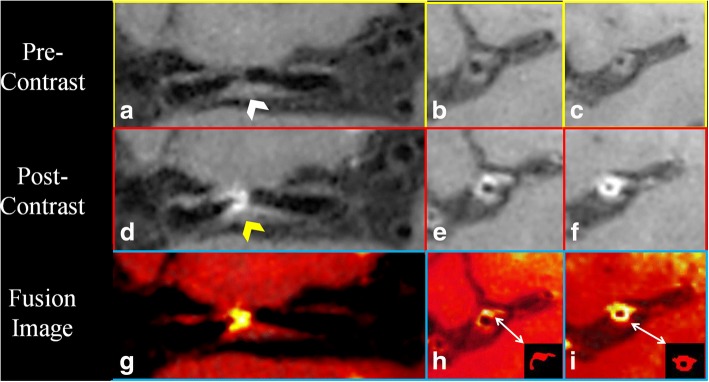

Pre- and post-contrast WB-HRCMR were first co-registered and two-dimensional short-axis images were then generated for the measurement of MCA plaque enhancement. Care was taken to ensure that the short-axis views of the plaque were perpendicular to the M1 segment of MCA. Fusion image of pre- and post-contrast WB-HRCMR have been utilized for the segmentation of the enhanced area of plaque and the enhancement volume was then calculated (Fig. 1). Enhancement index was calculated as follows: ([SIplaque/SInormal wall on postcontrast imaging] − [SIplaque/SInormal wall on matched precontrast imaging])/(SIplaque / SInormal wall on matched precontrast imaging).

Fig. 1.

Pre-contrast coronal and cross-sectional whole brain high resolution cardiovascular magnetic resonance (WB-HRCMR) images showed diffused plaque (a-c, white arrow) located on middle cerebral artery (MCA). Partial enhancement of the plaque was observed (d-f, yellow arrow). The enhancement plaque area was segmented through fusion images (h, i). The plaque enhanced volume was 11.02mm3

LSAs images were generated using five to six slices of minimum intensity projection (MinIP) in coronal direction with 10–15 mm thickness on pre-contrast WB-HRCMR. LSA branches longer than 5 mm were traced and analyzed by using these images [14]. When LSA branches less than 5 mm from the MCA origin, each branch was counted and measured separately, because more than 70% of branches were found to originate from common trunks [19].

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data were expressed as means ± standard deviations. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square test and continuous variables were compared using t-test between the two groups. A logistic regression analysis with the method of enter stepwise was used to look for independent predictors of stroke. A P-value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyzes were performed by using commercial software (SPSS 22.0, International Business Machnines, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

One hundred and one patients were consecutively recruited in the study and forty-nine patients were excluded from analysis due to poor image quality (N = 5), < 50% MCA stenosis (N = 4), evidence of cardio embolism (N = 7), patients with other etiologies (N = 13), and patients with lacunar infarction (N = 20). The remaining 52 patients were enrolled of which 29 were symptomatic. The demographic data was illustrated in Table 1. No statistically significant differences in patient demographics and the main clinical characteristics were found.

Table 1.

Demographic in symptomatic and asymptomatic ICAS patients

| Symptomatic ICAS (N = 29) | Asymptomatic ICAS (N = 23) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 46.00 ± 2.32 | 50.30 ± 2.36 | 0.397 |

| Male No. (%) | 20(69) | 13 (56.5) | 0.632 |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD, kg/cm2) | 24.86 ± 1.08 | 24.75 ± 0.74 | 0.939 |

| Hypertension No. (%) | 12(41.4) | 11(47.8) | 0.780 |

| Diabetes No. (%) | 4(13.8) | 4(17.4) | 1 |

| Hyperlipidemia No (%) | 10(34.5) | 9(39.1) | 0.778 |

| Smoker No. (%) | 15(51.7) | 11(47.8) | 0.477 |

| LDL-c (mean ± SD, mmol/L) | 2.23 ± 0.14 | 2.32 ± 0.15 | 0.274 |

| HDL-c (mean ± SD, mmol/L) | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 1.08 ± 0.08 | 0.203 |

| Triglycerides (mean ± SD, mmol/L) | 1.45 ± 0.12 | 1.43 ± 0.17 | 0.380 |

| Total cholesterol (mean ± SD, mmol/L) | 3.80 ± 0.17 | 3.67 ± 0.22 | 0.451 |

LDL-c Low Density Lipoprotein-cholesterol, HDL-c High Density Lipoprotein-cholesterol

ICAS plaque location

A total of seventy-nine ICAS plaques were observed. In symptomatic ICAS group, 29 (61.7%) plaques were found in MCA and 18 (38.3%) were in intracranial ICA. In asymptomatic ICAS group, 23 (71.8%) plaques were detected in MCA, 9 (28.2%) were in intracranial ICA. No statistically significant differences in MCA plaque distribution were found (P = 0.469) between the two groups. All culprit plaques in MCA were included for the final analysis.

ICAS plaque characteristics

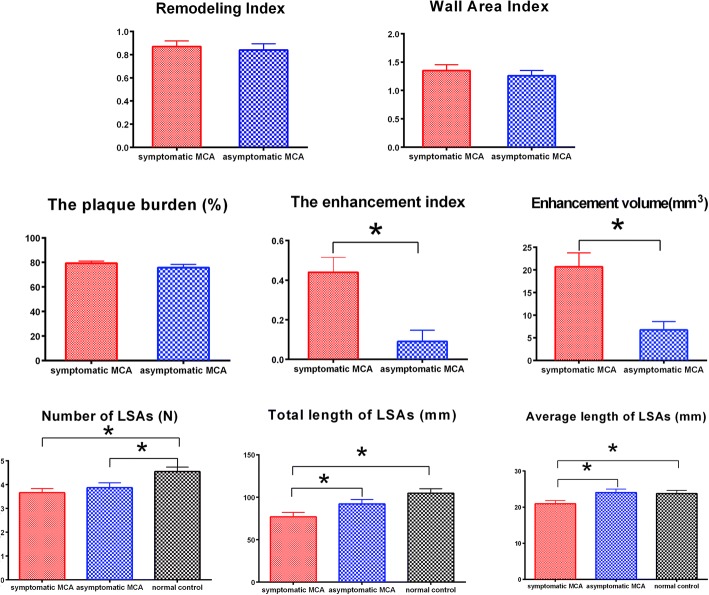

A total of fifty-two MCA plaques were included for the final analysis. The degrees of stenoses, RI, WA, and plaque burden did not differ significantly between two groups. Symptomatic MCA demonstrated greater plaque enhancement, including larger enhancement volume (20.70 ± 3.07 mm3 vs. 6.71 ± 1.87 mm3, P = 0.001) and higher enhancement index (0.44 ± 0.08 vs. 0.09 ± 0.06, P = 0.001) (Fig. 2). Two representative cases of symptomatic and asymptomatic MCA are presented in Figs. 3 and 4.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of remodeling index, wall area index, plaque burden, enhancement index, enhanced volume, number of lenticulostriate arteries (LSAs) and length of LSAs in symptomatic and asymptomatic MCA groups

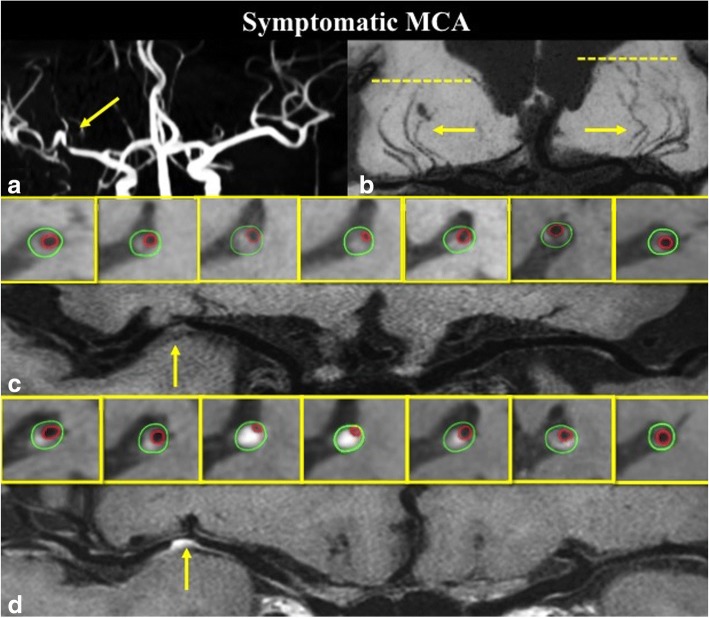

Fig. 3.

A 61 years old symptomatic ICAS patient with severe stenosis on right MCA (a), coronal MinIP revealed the decrease of right LSA branches compared to the left side (b); pre-contrast curved WB-HRCMR and cross-sectional images showed a plaque (c, arrow) on the MCA wall; Post-contrast WB-HRCMR showed extensive enhanced plaque volume which can be measured on corresponding cross-sectional images

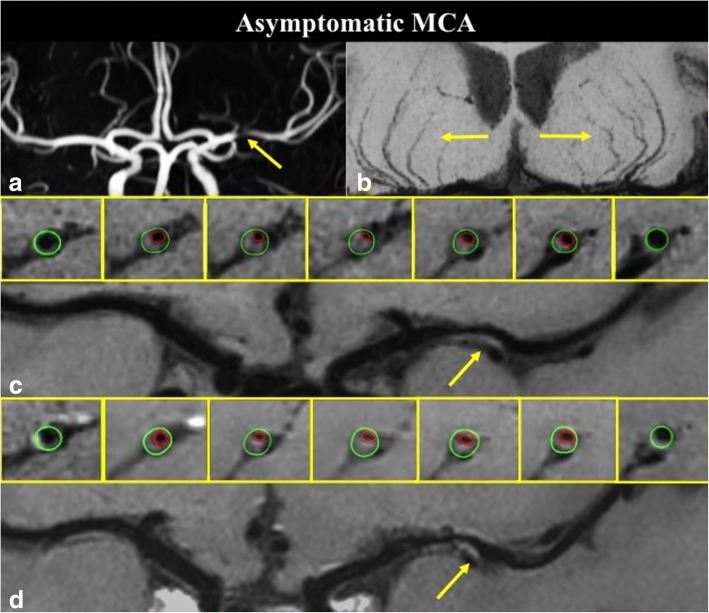

Fig. 4.

A 65 years old asymptomatic ICAS patient with severe stenosis on left MCA (a), coronal minimum intensity projection (MinIP) revealed symmetrical LSAs of the left and right hemispheres (b); pre-contrast curved WB-HRCMR and cross-sectional images showed a plaque (c, arrow) on the ventral and inferior side of MCA wall; post-contrast WB-HRCMR showed no enhancement

The LSAs features

In order to compare the several features of LSAs, twenty age-and sex-matched healthy subjects were included as normal controls. The mean number of LSAs was 3.65 ± 0.18 in symptomatic group, 3.87 ± 0.21 in asymptomatic group and 4.55 ± 0.19 on normal controls, respectively. There was significant difference between symptomatic group and normal controls (P = 0.002), and asymptomatic group also had statistical differences in LSAs branches compared with normal controls (P = 0.020). Symptomatic group had significant shorter total length of LSAs than normal controls (P < 0.001) but no difference was found between asymptomatic and normal groups (P = 0.111). The symptomatic group had shorter average length than both the asymptomatic groups (P = 0.02) and the normal controls (P = 0.034). Table 2 summarizes detailed characteristics of the two groups.

Table 2.

Plaque features and logistic regression analyses in symptomatic and asymptomatic ICAS

| Symptomatic ICAS (N = 29) | Asymptomatic ICAS (N = 23) | P value | Univariate Analysis OR(95%CI) | P value | Multivariable Analysis OR(95%CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of stenoses (mean ± SD, %) | 63.60 ± 2.80 | 63.94 ± 3.02 | 0.936 | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.424 | – | – |

| Remodeling index (mean ± SD,) | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.868 | 1.57(0.18–13.64) | 0.681 | – | – |

| Wall area index (mean ± SD) | 1.35 ± 0.10 | 1.26 ± 0.09 | 0.517 | 1.46(0.47–4.50) | 0.509 | – | – |

| Plaque burden (mean ± SD, %) | 79.39 ± 1.64 | 75.71 ± 2.68 | 0.227 | 1.03(0.98–1.09) | 0.238 | – | – |

| Enhancement volume (mean ± SD, mm3) | 20.70 ± 3.07 | 6.71 ± 1.87 | 0.001 | 1.02(1.02–1.18) | 0.005 | – | – |

| Enhancement index (mean ± SD) | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0.001 | 23.65(2.63–213.02) | 0.005 | 100.43 (4.02–2510.96) | 0.005 |

| Number of LSA (mean ± SD, N) | 3.65 ± 0.18 | 3.87 ± 0.21 | 0.433 | 0.80(0.44–1.41) | 0.425 | – | – |

| Total length of LSA (mean ± SD,mm) | 77.12 ± 5.16 | 92.16 ± 5.15 | 0.047 | 0.98(0.96–1.00) | 0.054 | – | – |

| Average length of LSA(mean ± SD,mm) | 20.95 ± 0.87 | 24.04 ± 0.95 | 0.020 | 0.86(0.76–0.98) | 0.027 | 0.80(0.65–0.99) | 0.036 |

OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval

Multivariate analysis

In a logistic regression analysis, the higher enhancement index and shorter average length of LSAs were independently associated with stroke. Odds ratios for enhancement index and average length of LSAs were 100.43 and 0.80 (95% confidence interval 4.02–2510.96 and 0.65–0.99; P = 0.005 and 0.036) respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we found that symptomatic MCA plaques exhibited a higher enhancement index and larger enhancement volume than the asymptomatic group. Furthermore, a significant reduction in the average number and length of LSAs in symptomatic ICAS groups was also found. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using WB-HRCMR to quantitatively explore the intracranial high risk plaque characteristics and LSA features in one imaging setting in ICAS patients.

Although variable refocusing flip angle sequences have been the most extensively studied 3D techniques for intracranial vessel wall imaging to date, it is still associated with inadequate suppression of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) signals and limited field of view. Some lesions may be missed, especially in the more distally vessels. This may cause an underestimation of the true intracranial plaque burden. WB-HRCMR technique allows for whole brain coverage, relatively high and isotropic spatial resolution, and more importantly, remarkable suppression of CSF and enhanced T1 contrast weighting. It enables the measurement of total intracranial plaque burden, plaque morphology and perforating arteries together.

Previous studies found that enhancement of an intracranial atherosclerotic plaque is associated with a recent ischemic event, and is independent of plaque thickness [20–24]. However, in most studies, the extent of plaque enhancement was not quantitatively measured [21, 24–26] and qualitative methods have been used to categorize the degree of plaque enhancement by comparing the enhancement of plaque and the pituitary on MR [25]. Our findings are in line with the these studies, however, with a step forward quantitative method. We registered and fused the pre- and post-contrast WB-HRCMR images and contour the enhanced plaque volume, accordingly. Thus, WB-HRCMR enables more accurate measurements of intracranial atherosclerosis plaques characteristics, such as enhancement index and the enhancement volume. We observed that symptomatic MCAs had higher enhancement index and larger enhanced volume of intracranial atherosclerosis plaques.

Recent studies have demonstrated that FSBB-MRA can be used to visualize LSAs [14–16, 27]. Our recent studies proved the feasibility of using whole-brain intracranial vessel wall imaging to depict LSA branches [17, 18]. The mean number of LSA branches on normal controls in our study was 4.55, which is consistent with Okuchi’s and Kang’s previous studies [15, 28]. Compared with normal controls, symptomatic MCAs had a significant decrease in the number and the length of LSAs.

There were several limitations in our study. First, this is an observational study and longitudinal studies are warranted to investigate and expound on the usage of WB-HRCMR in the prediction of stroke outcome and the risk of recurrent stroke. Secondly, the mechanism of plaque enhancement remains unclear and there is no pathological validation of the intracranial plaque vulnerability. Finally, due to the relatively limited spatial resolution used, it is difficult to evaluate the distal small perforating arteries. Partial volume effect of the volume measurement can be overcome by further optimizing imaging parameters or applying with higher field strength.

Conclusions

WB-HRCMR enabled the comprehensive quantitative evaluation of vessel wall lesions and the LSAs in stroke patients. Symptomatic MCAs have larger enhanced plaque volume, higher enhancement plaque index, and shorter length of LSAs compared with asymptomatic MCAs.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Haiqing Song, Dr. Qingfeng Ma from Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University for patients recruitment.

Funding

The study was partially support by National Institutes of Health grant number (5 R01 HL096119–07), National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1301702,2017YFC1307903), Capital Health Research and Development of Special (2016–1-1031),National Science Foundation of China (NSFC 91749127).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CTA

Computed tomography angiography

- DWI

Diffusion weighted imaging

- FSBB-MRA

Flow-sensitive black blood magnetic resonance angiography

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- HR-CMR

High-resolution cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging

- ICAS

Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis

- IR

Inversion-recovery

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- LSA

Lenticulostriate artery

- MCA

Middle cerebral artery

- MinIP

Minimum intensity projection

- MRA

Magnetic resonance angiography

- RCVS

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

- RI

Remodel index

- ROI

Region-of-interest

- SI

Signal intensity

- SPACE

Sampling Perfection with Application-optimized Contrast using different flip angle Evolutions

- TCD

Transcranial Doppler

- VA

Vessel area

- WA

Wall area

- WB-HRCMR

Whole-brain high-resolution cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Authors’ contributions

Drs QY and XG had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: DL, XJ, and QY. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: MW, HM, YY, ZF, FW. Drafting of the manuscript: MW, QY, XG. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: QY. Statistical analysis: HM. Administrative, technical, or material support: DL, XJ. Study supervision: QY, XG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects have consented to participate in this study. This research was approved by the Institutional Ethnics Committee for Human Research at Xuanwu Hospital (Beijing, China).

Consent for publication

All individual person’s data has consent for publication obtained from that person.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mengnan Wang, Email: wmn922@yeah.net.

Fang Wu, Email: fang_1989.127@163.com.

Yujiao Yang, Email: yangyjjean@163.com.

Huijuan Miao, Email: 1150965280@qq.com.

Zhaoyang Fan, Email: zhaoyang.fan@cshs.org.

Xunming Ji, Email: xunmingji2006@yeah.net.

Debiao Li, Email: debiao.li@cshs.org.

Xiuhai Guo, Email: guoxhxuan@126.com.

Qi Yang, Email: qi.yang@cshs.org, Email: yangyangqiqi@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Li H, Wong KS. Racial distribution of intracranial and extracranial atherosclerosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10(1):30–34. doi: 10.1016/S0967-5868(02)00264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qureshi AI, Caplan LR. Intracranial atherosclerosis. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):984–998. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldmann E, Daneault N, Kwan E, Ho KJ, Pessin MS, Langenberg P, Caplan LR. Chinese-white differences in the distribution of occlusive cerebrovascular disease. Neurology. 1990;40(10):1541–1545. doi: 10.1212/WNL.40.10.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wityk RJ, Lehman D, Klag M, Coresh J, Ahn H, Litt B. Race and sex differences in the distribution of cerebral atherosclerosis. Stroke. 1996;27:1974–1980. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.27.11.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasner SE, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, Stern BJ, Hertzberg VS, Frankel MR, Levine SR, Chaturvedi S, Benesch CG, et al. Predictors of ischemic stroke in the territory of a symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Circulation. 2006;113(4):555–563. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.578229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho M, Oliveira A, Azevedo E, Bastos-Leite AJ. Intracranial arterial stenosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(4):599–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubow JS, Salamon E, Greenberg E, Patsalides A. Mechanism of acute ischemic stroke in patients with severe middle cerebral artery atherosclerotic disease. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:1191–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sada S, Reddy Y, Rao S, Alladi S, Kaul S. Prevalence of middle cerebral artery stenosis in asymptomatic subjects of more than 40 years age group: a transcranial Doppler study. Neurol India. 2014;62(5):510–515. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.144443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mossa-Basha M, Hwang WD, De Havenon A, Hippe D, Balu N, Becker KJ, Tirschwell DT, Hatsukami T, Anzai Y, Yuan C. Multicontrast high-resolution vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging and its value in differentiating intracranial vasculopathic processes. Stroke. 2015;46(6):1567–1573. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu W-H, Li M-L, Gao S, Ni J, Zhou L-X, Yao M, Peng B, Feng F, Jin Z-Y, Cui L-Y. In vivo high-resolution MR imaging of symptomatic and asymptomatic middle cerebral artery atherosclerotic stenosis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen XY, Wong KS, Lam WW, Zhao HL, Ng HK. Middle cerebral artery atherosclerosis: histological comparison between plaques associated with and not associated with infarct in a postmortem study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25(1–2):74–80. doi: 10.1159/000111525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turan TN, Rumboldt Z, Granholm AC, Columbo L, Welsh CT, Lopes-Virella MF, Spampinato MV, Brown TR. Intracranial atherosclerosis: correlation between in-vivo 3T high resolution MRI and pathology. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237(2):460–463. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teng Z, Peng W, Zhan Q, Zhang X, Liu Q, Chen S, Tian X, Chen L, Brown AJ, Graves MJ, et al. An assessment on the incremental value of high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging to identify culprit plaques in atherosclerotic disease of the middle cerebral artery. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(7):2206–2214. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotoh K, Okada T, Miki Y, Ikedo M, Ninomiya A, Kamae T, Togashi K. Visualization of the lenticulostriate artery with flow-sensitive black-blood acquisition in comparison with time-of-flight MR angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29(1):65–69. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okuchi S, Okada T, Ihara M, Gotoh K, Kido A, Fujimoto K, Yamamoto A, Kanagaki M, Tanaka S, Takahashi R, et al. Visualization of lenticulostriate arteries by flow-sensitive black-blood MR angiography on a 1.5 T MRI system: a comparative study between subjects with and without stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(4):780–784. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuchi S, Okada T, Fujimoto K, Fushimi Y, Kido A, Yamamoto A, Kanagaki M, Dodo T, Mehemed TM, Miyazaki M, et al. Visualization of lenticulostriate arteries at 3T: optimization of slice-selective off-resonance sinc pulse-prepared TOF-MRA and its comparison with flow-sensitive black-blood MRA. Acad Radiol. 2014;21(6):812–816. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan Z, Yang Q, Deng Z, Li Y, Bi X, Song S, Li D. Whole-brain intracranial vessel wall imaging at 3 tesla using cerebrospinal fluid-attenuated T1-weighted 3D turbo spin echo. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(3):1142–1150. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Q, Deng Z, Bi X, Song SS, Schlick KH, Gonzalez NR, Li D, Fan Z. Whole-brain vessel wall MRI: a parameter tune-up solution to improve the scan efficiency of three-dimensional variable flip-angle turbo spin-echo. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;46(3):751–757. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marinkovic S, Gibo H, Milisavljevic M, Cetkovic M. Anatomic and clinical correlations of the Lenticulostriate arteries. Clin Anat. 2001;14:190–195. doi: 10.1002/ca.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi YJ, Jung SC, Lee DH. Vessel Wall imaging of the intracranial and cervical carotid arteries. J Stroke. 2015;17(3):238–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Skarpathiotakis M, Mandell DM, Swartz RH, Tomlinson G, Mikulis DJ. Intracranial atherosclerotic plaque enhancement in patients with ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(2):299–304. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natori T, Sasaki M, Miyoshi M, Ito K, Ohba H, Miyazawa H, Narumi S, Kabasawa H, Harada T, Terayama Y. Intracranial plaque characterization in patients with acute ischemic stroke using pre- and post-contrast three-dimensional magnetic resonance Vessel Wall imaging. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(6):1425–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryu CW, Kwak HS, Jahng GH, Lee HN. High-resolution MRI of intracranial atherosclerotic disease. Neurointervention. 2014;9(1):9–20. doi: 10.5469/neuroint.2014.9.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vakil P, Vranic J, Hurley MC, Bernstein RA, Korutz AW, Habib A, Shaibani A, Dehkordi FH, Carroll TJ, Ansari SA. T1 gadolinium enhancement of intracranial atherosclerotic plaques associated with symptomatic ischemic presentations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(12):2252–2258. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiao Y, Zeiler SR, Mirbagheri S, Leigh R, Urrutia V, Wityk R, Wasserman BA. Intracranial plaque enhancement in patients with cerebrovascular events on high- spatial-resolution MR images. Radiology. 2014;271;271(2):534–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Kim J-M, Jung K-H, Sohn C-H, Moon J, Shin J-H, Park J, Lee S-H, Han MH, Roh J-K. Intracranial plaque enhancement from high resolution vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging predicts stroke recurrence. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(2):171–179. doi: 10.1177/1747493015609775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akashi T, Taoka T, Ochi T, Miyasaka T, Wada T, Sakamoto M, Takewa M, Kichikawa K. Branching pattern of lenticulostriate arteries observed by MR angiography at 3.0 T. Jpn J Radiol. 2012;30(4):331–335. doi: 10.1007/s11604-012-0058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang CK, Park CA, Park CW, Lee YB, Cho ZH, Kim YB. Lenticulostriate arteries in chronic stroke patients visualised by 7 T magnetic resonance angiography. Int J Stroke. 2010;5(5):374–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.