Abstract

Registry or national dialysis data show that a sizeable proportion of contemporary dialysis patients have substantial levels of residual kidney function especially upon transitioning to dialysis therapy. However, among incident hemodialysis patients, the prevailing paradigm has been to initiate “full-dose” thrice-weekly treatment schedules irrespective of native kidney function in most developed countries. Recognizing the benefits of residual kidney function upon the health and survival of dialysis patients, there has been growing interest in incremental hemodialysis, in which dialysis frequency and dose are tailored according to the degree of patients’ residual kidney function. Infrequent hemodialysis can also be used for those who prefer a more conservative approach in managing uremia. Clinical practice guidelines support the use of twice-weekly hemodialysis among patients with adequate residual kidney function (renal urea clearance >3ml/min/1.73m2), and a growing body of evidence indicates that incremental hemodialysis is associated with better preservation of residual kidney function without adversely impacting survival. Nonetheless, incremental hemodialysis remains an underutilized approach in this population. In this review, we will discuss the history of the twice- versus thrice-weekly hemodialysis schedules; current clinical practice guidelines regarding infrequent hemodialysis; emerging data on incremental treatment regimens and outcomes; and guidelines for the practical implementation of incremental and infrequent hemodialysis in the clinical setting.

Keywords: incremental dialysis, infrequent dialysis, dialysis initiation, residual kidney function

INTRODUCTION

Each year, approximately 100,000 patients transition to hemodialysis as a live-saving therapy for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States (US).1 While a considerable number of patients may commence hemodialysis with substantial residual kidney function, the current paradigm in the US and most developed countries is to initiate “full-dose” thrice-weekly treatment schedules. However, an increasing body of evidence suggests that an incremental and infrequent hemodialysis schedule, in which dialysis frequency and dose are tailored according to degree residual kidney function, may be a more optimal regimen for patients initiating treatment with considerable native kidney function.2–11 Those who prefer a more conservative hemodialysis treatment approach may also prefer the infrequent hemodialysis regimen such as once to twice-weekly dialysis sessions. The objectives of this review are to discuss the origins of the twice- versus thrice-weekly hemodialysis schedule; current clinical practice guidelines regarding hemodialysis frequency; rationale for incremental and infrequent hemodialysis regimens and emerging data on relevant outcomes; and recommendations on its implementation in clinical practice.

HISTORY OF THRICE-WEEKLY HEMODIALYSIS

Through a process of trial and error, the thrice-weekly hemodialysis schedule evolved into the standard of care for dialysis treatment approximately one-half century ago.10 In 1960, the initial maintenance hemodialysis patients received dialysis treatment every five to seven days following Dr. Scribner’s innovation of the first permanent vascular access device at the University of Washington.12,13 Due to complications of peripheral neuropathy ensuing from retained uremic toxins and malignant hypertension resulting from volume overload under this once-weekly schedule, hemodialysis frequency was increased to two-times-per-week with 12 to 20 hour treatment sessions. However, this 12 to 20 hour twice-weekly schedule proved to be taxing to patients, prompting their providers to shift towards six to eight hour three-times-per-week overnight hemodialysis schedules based on the experiences of colleagues in London who first prescribed overnight dialysis treatment.14

By the time that the United States Congress passed legislation for Medicare’s ESRD Program in 1972, with subsequent launching of the program in 1973, the three-times-per-week schedule was considered to be the optimal regimen in administering hemodialysis.8,12,13 Thought to be the best concession for providing adequate dialysis to the greatest number of ESRD patients with limited resources, the thrice-weekly hemodialysis schedule has remained the prevailing paradigm for past five decades.

ADEQUACY TARGETS: CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES

While recommendations from the 1997 National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) Hemodialysis Adequacy Group endorsed dialysis initiation at a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 10ml/min/1.73m2,15 a more recent 2006 KDOQI guidelines statement has indicated that dialysis initiation may be indicated at higher levels of GFR (<15ml/min/1.73m2) in the setting of symptoms or declining health associated with loss of kidney function.16 Consequently, a greater proportion of contemporary dialysis patients may be initiating renal replacement therapy with higher levels of residual kidney function. Indeed, United States Renal Data System (USRDS) data show that, among patients initiating hemodialysis in the United States in 2013, as many as 40% had estimated GFRs exceeding 10ml/min/1.73m2.17

Among patients lacking substantial residual kidney function, defined as a residual urea clearance (KRU) of <2ml/min/1.73m2, KDOQI guidelines recommended a single pool Kt/V of 1.2 to 1.4 per session as minimally adequate and target dialysis doses, respectively, with a minimum treatment time of three hours per session; guidelines advise against a less than thrice-weekly hemodialysis schedule in these patients.16 Among patients with substantial residual kidney function (KRU of >3ml/min/1.73m2), the 2006 KDOQI guidelines indicated that the minimal session single pool Kt/V can be reduced (i.e., dose reduction to 60% of the minimum target of those without residual kidney function) and twice-weekly hemodialysis would be permissible. Hence, twice-weekly hemodialysis may be advised if KRU exceeds 3 ml/min/1.73m2, based on the ability to achieve a single pool Kt/V of >1.2 as well as a weekly standard Kt/V of >2.2 with a hemodialysis treatment time of four hours, but it should not continue once KRU drops below 2 ml/min/1.73m2.16,18 Among patients who are prescribed infrequent (less than thrice-weekly) hemodialysis schedules due to substantial residual kidney function, the 2006 KDOQI guidelines recommend that KRU be rechecked at least quarterly and following any event that may be associated with an abrupt decline in residual kidney function.16

RESIDUAL KIDNEY FUNCTION AND RATIONALE FOR THE INCREMENTAL DIALYSIS REGIMEN

Despite these guidelines, the current norm in the US until recently has been to initiate hemodialysis patients on a full-dose, three-times-per week schedule irrespective of underlying kidney function. However, an incremental hemodialysis schedule, in which hemodialysis frequency and dose are tailored according to degree residual kidney function, may be a preferred means of preserving native kidney function in patients initiating dialysis.3,4,8,10 Twice-weekly hemodialysis can also be used for those patients who prefer a more conservative management approach regardless of residual kidney function, particularly amongst those who would otherwise decline dialysis therapy if it were a thrice-weekly regimen. Hence, this approach may serve as a compromise and an alternative to categorical decline or withdrawal of dialysis therapy.

It is thought that hemodialysis in and of itself promotes loss of residual kidney function due to (1) ischemic insult caused by intra-dialytic hypotension and post-dialysis hypovolemia, (2) release of nephrotoxic inflammatory mediators during the hemodialysis procedure, (3) reduction in circulating urea leading due a reduction in osmotic diuresis, and (4) deactivation of remaining nephrons.19–22 While some data indicate that residual kidney function may be better preserved among hemodialysis patients than previously thought (70% and 14 to 20% of patients retaining residual kidney function one and three to five years after dialysis initiation, respectively23), other studies suggest that hemodialysis patients experience a more rapid decline in native kidney function vs. peritoneal dialysis patients.20 Recent data also suggest that frequent hemodialysis accelerates residual renal function decline. In a corollary study of the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Nocturnal trial, among non-anuric patients, patients assigned to frequent hemodialysis (i.e., six-times-per-week) had greater loss of residual kidney function, ascertained by urine volume, urea clearance, and creatinine clearance, compared to those prescribed conventional (i.e., three-times-per-week) hemodialysis at four and 12 months follow up.24 Furthermore, patients in the frequent hemodialysis arm had a lower nadir intradialytic systolic blood pressure vs. the conventional group, suggesting that ischemic kidney damage may have been contributory.

Given its continuous nature, residual kidney function offers considerable benefits with respect to volume control, solute clearance, and uremic toxin removal even among patients receiving dialysis.25 For example, greater native kidney function may reduce the likelihood of large interdialytic weight gains, resulting in lower ultrafiltration rates, intradialytic hypotension, and myocardial stunning.23,26–28 Lesser interdialytic fluid accumulation may also lead to better overall fluid balance and reduced left ventricular hypertrophy as a substrate for malignant ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.29 In addition, residual kidney function provides greater clearance of middle and large molecular weight solutes vs. hemodialysis, and thereby may result in better phosphorus control.28,30,31 This may in turn allow for more dietary liberalization, leading to improved nutritional status and better health-related quality of life.10 Furthermore, substantial residual kidney function may be associated with improved anemia parameters and lower erythropoietin-stimulating requirements, as well as reduced inflammatory status.32

A mounting body of data has demonstrated the importance of residual kidney function upon the survival and health-related quality of life of both peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis patients (Table 1).23,32–38 With respect to patients newly initiating hemodialysis, Shafi et al. examined the relationship between residual kidney function, defined as urine output >250ml, with clinical outcomes among 734 incident hemodialysis patients across 81 dialysis clinics from the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) cohort.32 Among patients who had urine output >250ml at baseline (84% of the cohort), presence of urine output was not associated with better survival but was linked with better health-related quality of life. However, among a subcohort of 579 patients with one-year urine output data, those with preservation of urine output >250ml (28% of the cohort) had a 30% lower all-cause death risk, as well as a trend towards lower cardiovascular mortality.

Table 1.

Selected studies of residual kidney function and/or residual urine output and outcomes in dialysis patients.

| Author (Year) | Study Population (N) | Exposure | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bargman et al. (2001)33 | PD patients (CANUSA study) |

RKF UOP |

|

| Shemin et al. (2001)36 | 114 prospective HD patients | RKF defined as renal urea clearance and renal creatinine clearance |

|

| Paniagua et al. (2002)35 | PD patients (ADEMEX trial) |

RKF |

|

| Termorshuizen et al. (2004)37 | 740 incident HD patients (NECOSAD cohort) |

RKF defined as renal Kt/V urea |

|

| Vilar et al. (2009)23 | 650 incident HD patients | RKF defined as renal urea clearance |

|

| Shafi et al. (2010)32 | 734 incident HD patients (CHOICE cohort) |

UOP |

|

| Van der Wal et al. (2011)38 | 1191 incident HD patients & 609 incident PD patients (NECOSAD cohort) |

RKF defined as mean of renal urea and creatinine clearance |

|

| Obi et al. (2016)34 | 6538 incident HD patients from an LDO | RKF defined as renal urea clearance UOP |

|

Abbreviations: PD, peritoneal dialysis; CANUSA, Canada-USA; RKF, residual kidney function; UOP, urine output; ADEMEX, Adequacy of Peritoneal Dialysis in Mexico; HD, hemodialysis; NECOSAD, Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis; CHOICE, Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease; ESA, erythropoietin-stimulating agent; LDO, large dialysis organization.

A subsequent study of 6538 incident hemodialysis patients by Obi et al. from a large US dialysis organization examined the association between one-year and annual change in residual kidney function (defined by renal urea clearance and urine volume at baseline and one year follow up) with survival.34 The investigators found that higher renal urea clearance and urine volume one year after hemodialysis initiation was associated with better survival independent of case-mix characteristics, ultrafiltration rate, and laboratory data. They also observed a gradient association between loss of renal urea clearance, such that those with a decline of 6.0 and 3.0ml/min/1.73m2/year had a 2.0-fold and 1.25-fold higher mortality risk, respectively, while those who had no change or a rise of 3.0ml/min/1.73m2/year had a 19% and 39% lower mortality risk, respectively (reference: renal urea clearance decline of 1.5ml/min/1.73m2/year). A similar pattern of findings was observed for annual change in urine output.

INCREMENTAL HEMODIALYSIS AND OUTCOMES

This concept of “incremental dialysis” was first described amongst peritoneal dialysis patients, in whom residual kidney function has been used as a guide to establish and adjust the dialysis prescription.39,40 Using an individualized, patient-centered approach, both native kidney function and dialysis clearance are included in the total weekly clearance target, and upon loss of residual kidney function the peritoneal dialysis prescription is escalated. Similarly, the assessment of hemodialysis adequacy should also incorporate dialysis session dialysis dose and duration, frequency of hemodialysis, and amount of residual kidney function.41 Indeed, a number of studies have examined the relationship between incremental hemodialysis regimens (i.e., once- and twice-weekly dialysis) with relevant clinical outcomes such as preservation of residual kidney function and mortality in dialysis patients (Table 2).2,5–7,9,11

Table 2.

Selected studies of incremental hemodialysis, residual kidney function, and mortality.

| RESIDUAL KIDNEY FUNCTION | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author (Year) | Study Population | Treatment Frequency | Findings |

| Lin et al. (1999)6 | 74 prevalent HD patients (Taiwan) |

Twice- vs. thrice-weekly |

|

| Zhang et al. (2014)11 | 85 incident HD patients (Shanghai) |

Twice- vs. thrice-weekly |

|

| Obi et al. (2016)9 | 8419 incident HD patients (United States) |

Twice- vs. thrice-weekly (matched) |

|

| MORTALITY | |||

| Author (Year) | Study Population | Treatment Frequency | Findings |

| Hanson et al. (1999)2 | 15,067 incident and prevalent HD (United States) |

Twice-weekly vs. thrice-weekly |

|

| Lin et al. (2012)5 | 1288 incident and prevalent HD patients (Shanghai) |

Twice-weekly vs. thrice-weekly |

|

| Obi et al. (2016)9 | 8419 incident HD patients (United States) |

Twice- vs. thrice-weekly (matched cohort) |

|

| Mathew et al. (2016)7 | 50,756 incident HD patients (United States) |

Incremental (≤2 times-per-week) vs. conventional (3 times-per-week) vs. frequent (≥4 times-per-week) (matched cohort) |

|

Abbreviations: HD, hemodialysis; RKF, residual kidney function.

Residual Kidney Function

In a Taiwanese study of 74 prevalent hemodialysis patients who maintained the same treatment schedules over time by Lin et al., the rate of residual kidney function decline (defined by creatinine clearance and urine output) was compared among patients prescribed twice vs. thrice-weekly therapy with similar baseline creatinine clearance levels and urine output.6 After a mean follow up of 18 months, patients receiving twice-weekly hemodialysis had a slower rate of residual kidney function decline vs. those receiving thrice-weekly hemodialysis. However, it should be noted that this study did not account for differences in socio-demographics nor comorbidities between the two groups.

A subsequent study of 85 incident hemodialysis patients in Shanghai by Zhang et al. compared the trajectory of residual kidney function defined by urine output amongst patients who were initiated and maintained on twice-weekly hemodialysis for six months or longer vs. those who were initiated and maintained on thrice-weekly hemodialysis over the entire study period.11 At baseline, the proportion of patients with residual kidney function (defined as urine output ≥200ml/day) was greater in patients receiving twice-weekly vs. thrice-weekly hemodialysis. Over the course of one year, the proportion of patients with residual kidney function loss (urine volume <200ml/day) was lower, and the time to residual kidney function loss was longer among patients initiated on twice vs. thrice-weekly hemodialysis. In a subcohort of 48 incident hemodialysis patients (vintage <12 months) whose baseline urine output was >500 ml/day, each additional hemodialysis session per week was found to be associated with a 7.2-fold higher risk of residual kidney function loss (defined as urine output <200ml/day).

Most recently, in a study of 23,645 incident hemodialysis patients from a large US dialysis organization, Obi et al. examined the relationship between an incremental hemodialysis regimen (defined as greater than six consecutive weeks of twice-weekly hemodialysis in the first quarter of dialysis) vs. conventional regimen (defined as thrice-weekly hemodialysis) with preservation of residual kidney function (ascertained by KRU and urine volume) over the course of one year.9 Roughly half of patients with baseline KRU data who survived the first year (N=23,645) had sufficient residual kidney function to qualify for twice-weekly hemodialysis, but the overall prescription of this regimen was quite low (<2%) over the study period. Among 351 patients receiving incremental regimens who were matched on the basis of baseline KRU, urine volume, age, sex, race, vascular access type, and diabetes to 8068 patients receiving conventional regimens, those receiving incremental hemodialysis showed slower decline in residual kidney function over time in multivariable adjusted models. More specifically, patients receiving incremental hemodialysis had a 16% and 15% higher KRU and urine volume in the second quarter, and these differences persisted over the subsequent quarters.

Mortality

In a study of 15,067 incident and prevalent hemodialysis patients from the US Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Study cohort by Hanson et al., the investigators examined the relationship between twice-weekly vs. thrice-weekly hemodialysis and mortality risk among patients stratified by dialysis vintage.2 Among prevalent hemodialysis patients, twice-weekly treatment was associated with lower mortality risk; however, patients in the twice-weekly group had more favorable patient characteristics, and analyses did not account for differences in residual kidney function between the two groups. However, in a separate analysis of incident hemodialysis patients that did account for residual kidney function, twice-weekly vs. thrice-weekly treatments demonstrated similar mortality risk. In a smaller but more contemporary cohort of 1288 hemodialysis from the Shanghai Renal Registry, the association between twice-weekly vs. thrice-weekly hemodialysis with mortality was also examined according to dialysis vintage.5 In adjusted analyses of the overall cohort, twice-weekly vs. thrice-weekly hemodialysis showed similar mortality risk. In unadjusted analyses that stratified patients according to duration of dialysis, twice-weekly vs. thrice-weekly hemodialysis demonstrated longer survival times amongst both incident and prevalent (vintage >5 months) patients; however, these data provide limited inference due to non-consideration of confounders and lack of information on residual kidney function.

Similar to the US Morbidity and Mortality substudy, the aforementioned study by Obi et al. examined the relationship between incremental vs. conventional hemodialysis schedules and mortality risk. In the overall cohort (351 incremental hemodialysis patients matched to 8068 conventional hemodialysis patients), there was no difference in mortality risk between the two groups.9 However, in subgroup analyses stratified by residual kidney function, incremental hemodialysis was associated with a 61% mortality risk among patients with “inadequate residual kidney function” (defined as KRU ≤3ml/min/1.73m2 or urine volume ≤600ml/day). However, in those with “adequate residual kidney function” (defined as KRU >3/min/1.73m2 or urine volume >600ml/day), incremental vs. conventional hemodialysis were associated with similar mortality risk. Notably, a significant trend towards better survival was observed across incrementally higher renal urea clearance levels and incrementally lower weekly interdialytic weight gains.

Most recently, Mathew et al. examined mortality risk across a spectrum of hemodialysis frequency schedules among a matched cohort of 434, 50,162, and 160 incident hemodialysis patients receiving incremental, conventional, and frequent treatments.7 After accounting for residual kidney function, patients receiving incremental hemodialysis were found to have a similar mortality risk vs. those receiving conventional schedules. However, patients receiving frequent hemodialysis had a 56% higher mortality risk than the incremental group. Notably, comorbidity burden was observed to be an important modifier of treatment schedule and mortality. Among patients with higher Charlson Comorbidity Scores ≥5, incremental hemodialysis was associated with a 77% higher death risk. However, among patients with low or moderate comorbidity burden, there was no difference in survival among the incremental vs. conventional treatment groups.

PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATION OF INCREMENTAL DIALYSIS

Given the benefits of residual kidney function upon the health and survival of ESRD patients, there is compelling rationale to consider incremental and infrequent hemodialysis regimens as a new paradigm for dialysis initiation or conservative dialysis in appropriately-selected patients. In most of the aforementioned studies, incremental dialysis was associated with equivalent to better survival vs. conventional treatments.2,5,7,9 However, it is important to note that higher mortality risk was observed among patients with inadequate residual kidney function and higher comorbidity burden.7,9

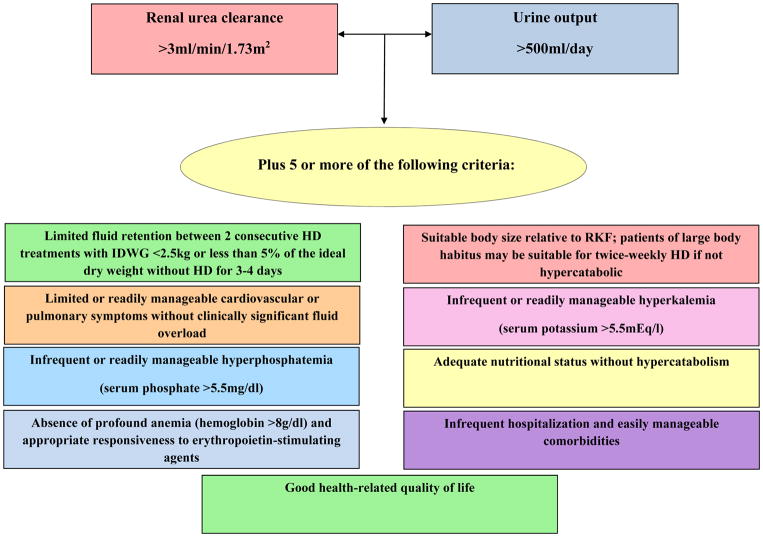

To provide guidance in the optimal implementation of incremental hemodialysis, experts in the field have proposed practical criteria that can be used to identify patients who are suitable for this regimen (Figure 1).4 In addition to the 2006 KDOQI guideline’s definitions of adequate residual kidney function defined by KRU for twice-weekly hemodialysis,16 the presence of substantial urine volume (>500ml/day) is an important criteria given the potential risk of high interdialytic weight gains and volume overload with less frequent hemodialysis regimens.4 In addition to having adequate KRU and urine volume, experts have also advised that patients should meet most (i.e., five out of nine) of the following criteria to qualify for incremental hemodialysis: (1) Limited fluid retention between two consecutive hemodialysis sessions with a fluid gain <2.5kg or <5% of ideal dry weight without hemodialysis for three to four days; (2) limited or readily manageable cardiovascular or pulmonary symptoms without clinically significant fluid overload; (3) suitable body size relative to residual kidney function (i.e., patients of large body habitus may be suitable for twice-weekly hemodialysis if not hypercatabolic); (4) infrequent or readily manageable hyperkalemia (serum potassium >5.5mEq/l); (5) infrequent or readily manageable hyperphosphatemia (serum phosphate >5.5mg/dl); (6) adequate nutritional status without hypercatabolism; (7) absence of profound anemia (hemoglobin >8g/dl) and appropriate responsiveness to erythropoietin-stimulating agents; (8) infrequent hospitalization and easily manageable comorbidities; and (9) good health-related quality of life.

Figure 1. Proposed criteria for implementation of incremental hemodialysis.4,16.

Abbreviations: IDWG, interdialytic weight gain; HD, hemodialysis; RKF, residual kidney function.

It is important to highlight that frequent (i.e., at least quarterly) assessment of residual kidney function is a cornerstone of the incremental hemodialysis prescription.4,16,18,42 As residual kidney function will inevitably decline over time, patients initiating twice-weekly hemodialysis may ultimately need to transition to thrice-weekly or more frequent schedules. Hence, patients should receive ample education that at the point that their residual kidney function can no longer compensate for a less frequent hemodialysis schedule, their dialysis frequency and dose will need to be adjusted accordingly. Given the differential rates of native kidney function decline over time, as well as the potential harms of applying incremental hemodialysis to incorrect patient populations (e.g., volume overload leading to ventricular hypertrophy, high ultrafiltration rates/myocardial stunning, hyperkalemia, cardiovascular disease and death), routine assessment of residual kidney function is imperative in identifying the appropriate transition point from a twice-weekly to thrice-weekly schedule for each patient.

CONCLUSIONS

While a growing body of evidence suggests that incremental and infrequent hemodialysis regimens are associated with better preservation of residual kidney function without adversely impacting survival, further research is needed in multiple areas to define its optimal implementation on a broad scale. Rigorous studies are needed to examine how infrequent hemodialysis influences other relevant endpoints, including patient-centered outcomes such as health-related quality of life, mental health, physical function, and cognition, as well as cost-effectiveness.10 Given the challenges of routinely measuring 24-hour urine urea and creatinine clearances and urine output, future research is needed to identify innovative, straightforward, and accurate methods of residual kidney function assessment in the clinical setting.18,42 Considerable study is also needed to determine the optimal patient phenotype for incremental hemodialysis, as well as more precisely defining the appropriate transition points from twice-weekly to more frequent hemodialysis schedules.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The authors are supported by research grants from the NIH/NIDDK (K23-DK102903 [CMR], K24-DK091419 [KKZ], R01-DK096920 [KKZ], U01-DK102163 [KKZ]) as well as philanthropic support from Mr. Louis Chang and Dr. Joseph Lee.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: No relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2016 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson JA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Ojo AO, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Agodoa LY, et al. Prescription of twice-weekly hemodialysis in the USA. American journal of nephrology. 1999;19(6):625–633. doi: 10.1159/000013533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Casino FG. Let us give twice-weekly hemodialysis a chance: revisiting the taboo. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2014 Sep;29(9):1618–1620. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Unruh M, Zager PG, Kovesdy CP, Bargman JM, Chen J, et al. Twice-weekly and incremental hemodialysis treatment for initiation of kidney replacement therapy. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2014 Aug;64(2):181–186. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin X, Yan Y, Ni Z, Gu L, Zhu M, Dai H, et al. Clinical outcome of twice-weekly hemodialysis patients in shanghai. Blood purification. 2012;33(1–3):66–72. doi: 10.1159/000334634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin YF, Huang JW, Wu MS, Chu TS, Lin SL, Chen YM, et al. Comparison of residual renal function in patients undergoing twice-weekly versus three-times-weekly haemodialysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2009 Feb;14(1):59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathew A, Obi Y, Rhee CM, Chen JL, Shah G, Lau WL, et al. Treatment frequency and mortality among incident hemodialysis patients in the United States comparing incremental with standard and more frequent dialysis. Kidney international. 2016 Nov;90(5):1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obi Y, Eriguchi R, Ou SM, Rhee CM, Kalantar-Zadeh K. What Is Known and Unknown About Twice-Weekly Hemodialysis. Blood purification. 2015;40(4):298–305. doi: 10.1159/000441577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obi Y, Streja E, Rhee CM, Ravel V, Amin AN, Cupisti A, et al. Incremental Hemodialysis, Residual Kidney Function, and Mortality Risk in Incident Dialysis Patients: A Cohort Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2016 Aug;68(2):256–265. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhee CM, Unruh M, Chen J, Kovesdy CP, Zager P, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Infrequent dialysis: a new paradigm for hemodialysis initiation. Seminars in dialysis. 2013 Nov-Dec;26(6):720–727. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang M, Wang M, Li H, Yu P, Yuan L, Hao C, et al. Association of initial twice-weekly hemodialysis treatment with preservation of residual kidney function in ESRD patients. American journal of nephrology. 2014;40(2):140–150. doi: 10.1159/000365819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blagg CR. The early history of dialysis for chronic renal failure in the United States: a view from Seattle. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2007 Mar;49(3):482–496. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scribner BH, Cole JJ, Ahmad S, Blagg CR. Why thrice weekly dialysis? Hemodialysis international. International Symposium on Home Hemodialysis. 2004 Apr 01;8(2):188–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2004.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaldon S. Experience to date with home hemodialysis. In: Scribner BH, editor. Proceedings of the Working Conference on Chronic Dialysis. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1964. pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.NKF-DOQI clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy. National Kidney Foundation. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1997 Sep;30(3 Suppl 2):S15–66. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)70027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy, update 2006. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2006 Jul;48( Suppl 1):S2–90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2015 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew AT, Fishbane S, Obi Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Preservation of residual kidney function in hemodialysis patients: reviving an old concept. Kidney international. 2016 Aug;90(2):262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golper TA, Mehrotra R. The intact nephron hypothesis in reverse: an argument to support incremental dialysis. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2015 Oct;30(10):1602–1604. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansen MA, Hart AA, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. Predictors of the rate of decline of residual renal function in incident dialysis patients. Kidney international. 2002 Sep;62(3):1046–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lysaght MJ, Vonesh EF, Gotch F, Ibels L, Keen M, Lindholm B, et al. The influence of dialysis treatment modality on the decline of remaining renal function. ASAIO transactions. 1991 Oct-Dec;37(4):598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeh BP, Tomko DJ, Stacy WK, Bear ES, Haden HT, Falls WF., Jr Factors influencing sodium and water excretion in uremic man. Kidney international. 1975 Feb;7(2):103–110. doi: 10.1038/ki.1975.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vilar E, Wellsted D, Chandna SM, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Residual renal function improves outcome in incremental haemodialysis despite reduced dialysis dose. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2009 Aug;24(8):2502–2510. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daugirdas JT, Greene T, Rocco MV, Kaysen GA, Depner TA, Levin NW, et al. Effect of frequent hemodialysis on residual kidney function. Kidney international. 2013 May;83(5):949–958. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rottembourg J. Residual renal function and recovery of renal function in patients treated by CAPD. Kidney international. Supplement. 1993 Feb;40:S106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burton JO, Jefferies HJ, Selby NM, McIntyre CW. Hemodialysis-induced cardiac injury: determinants and associated outcomes. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2009 May;4(5):914–920. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03900808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konings CJ, Kooman JP, Schonck M, Struijk DG, Gladziwa U, Hoorntje SJ, et al. Fluid status in CAPD patients is related to peritoneal transport and residual renal function: evidence from a longitudinal study. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2003 Apr;18(4):797–803. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vilar E, Farrington K. Emerging importance of residual renal function in end-stage renal failure. Seminars in dialysis. 2011 Sep-Oct;24(5):487–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fagugli RM, Pasini P, Quintaliani G, Pasticci F, Ciao G, Cicconi B, et al. Association between extracellular water, left ventricular mass and hypertension in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2003 Nov;18(11):2332–2338. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babb AL, Ahmad S, Bergstrom J, Scribner BH. The middle molecule hypothesis in perspective. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1981 Jul;1(1):46–50. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(81)80011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bargman JM, Golper TA. The importance of residual renal function for patients on dialysis. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2005 Apr;20(4):671–673. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shafi T, Jaar BG, Plantinga LC, Fink NE, Sadler JH, Parekh RS, et al. Association of residual urine output with mortality, quality of life, and inflammation in incident hemodialysis patients: the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2010 Aug;56(2):348–358. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bargman JM, Thorpe KE, Churchill DN. Relative contribution of residual renal function and peritoneal clearance to adequacy of dialysis: a reanalysis of the CANUSA study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2001 Oct;12(10):2158–2162. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obi Y, Rhee CM, Mathew AT, Shah G, Streja E, Brunelli SM, et al. Residual Kidney Function Decline and Mortality in Incident Hemodialysis Patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2016 Dec;27(12):3758–3768. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015101142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paniagua R, Amato D, Vonesh E, Correa-Rotter R, Ramos A, Moran J, et al. Effects of increased peritoneal clearances on mortality rates in peritoneal dialysis: ADEMEX, a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2002 May;13(5):1307–1320. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1351307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shemin D, Bostom AG, Laliberty P, Dworkin LD. Residual renal function and mortality risk in hemodialysis patients. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2001 Jul;38(1):85–90. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.25198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Termorshuizen F, Dekker FW, van Manen JG, Korevaar JC, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. Relative contribution of residual renal function and different measures of adequacy to survival in hemodialysis patients: an analysis of the Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD)-2. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2004 Apr;15(4):1061–1070. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000117976.29592.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Wal WM, Noordzij M, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT, Korevaar JC, et al. Full loss of residual renal function causes higher mortality in dialysis patients; findings from a marginal structural model. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2011 Sep;26(9):2978–2983. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agrawal A, Saran R, Nolph KD. Continuum and integration of pre-dialysis care and dialysis modalities. Peritoneal dialysis international : journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 1999;19( Suppl 2):S276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehrotra R, Nolph KD, Gotch F. Early initiation of chronic dialysis: role of incremental dialysis. Peritoneal dialysis international : journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 1997 Sep-Oct;17(5):426–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keshaviah PR, Emerson PF, Nolph KD. Timely initiation of dialysis: a urea kinetic approach. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1999 Feb;33(2):344–348. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toth-Manikowski SM, Shafi T. Hemodialysis Prescription for Incident Patients: Twice Seems Nice, But Is It Incremental? American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2016 Aug;68(2):180–183. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]